Abstract

Background

Female athletes participating in sports emphasising aesthetics are potentially more prone to developing disordered eating (DE) and eating disorders (EDs) than non-athletes, males, and those participating in sports with less emphasis on leanness. Despite this, female bodybuilding athletes have received little attention.

Aim

To investigate differences in eating attitudes, behaviours and beliefs in female bodybuilding athletes and a non-athlete group.

Methods

A cross-sectional study design was used with the eating attitude test-26 (EAT-26) distributed to 75 women (49.3% bodybuilding athletes; 50.7% non-athletes) and the female athlete screening tool (FAST) distributed to the female bodybuilding group only.

Results

Demographic characteristics revealed no significant difference in age, stature or body mass index (P = 0.106 to 0.173), though differences in body mass were evident (P = 0.0001 to 0.042). Bodybuilding athletes scored significantly higher (P = 0.001) than non-athletes on the EAT-26 questionnaire, with significantly more athletes (56.8%) being labelled as ‘at risk’ of an ED than non-athletes (23.7%, P = 0.001). Responses to the FAST questionnaire indicated female bodybuilding athletes have high preoccupation with their body mass; engage in exercise to alter their body mass; and disclosed negative perceptions of themselves.

Conclusion

In all, female bodybuilding athletes demonstrate behaviours associated with DE and EDs as well as a preoccupation with nutrition intake, exercise, and strategies to alter their appearance. These findings have important implications for those managing female bodybuilding athletes such as strength and conditioning coaches, athletic trainers, nutritionist and dietitians with respect to detecting DE and EDs as well as minimising the risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Participation in sports is often perceived as a healthy pursuit that helps promote physical, mental, and social wellbeing [1, 2]. However, sports where competition success is influenced by aesthetics (e.g., bodybuilding) places added pressure on athletes to look a certain way to meet the requirements of governing bodies, expectations of coaches and judges, and the perception of teammates, family and the media [3,4,5,6]. These pressures, combined with high training loads, extreme dieting or weight-loss strategies, and psychopathological traits, can increase the risk of disordered eating (DE) and eating disorders (EDs) [6, 7].

Eating disorders can be categorised into three separate clinical disorders; anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa; and eating disorder not otherwise specified [8]; whereas, the term DE refers to a pattern of abnormal and irregular eating behaviours used in an effort to obtain or maintain a lower than usual body weight [9]. Examples of DE include behaviours such as binge eating [10], restrictive eating [7], and having concerns about body image. Both DE and EDs can have negative health implications that are, amongst others, associated with macro- and micro-nutrient deficiencies, menstrual irregularities and bone demineralization [11, 12]. It is an ongoing challenge for those working (i.e. strength and conditioning coaches, athletic training and nutritionists) and competing in sport to recognise, prevent, and manage DE and EDs.

Sundgot–Borgen [7] showed a significantly higher percentage of athletes competing in weight-based or aesthetic sports met the criteria for an ED when compared to ball games, technical-, endurance-, power-sports, and controls. Similarly, Byrne and McLean [13] found that a greater proportion of athletes participating in ‘thin build’ sports, where the emphasis on leanness is high, (e.g., ballet, swimming, and long-distance running) met the criteria for an ED when compared to ‘normal build’ and controls (31% cf. 8.5% cf. 5.5%), both of which has less focus on leanness. It also appears there is an association between sex and the risk of DE and EDs, with female athletes being at greater risk when compared with male athletes [7, 13,14,15].

Unlike other sports where manipulation of training or dietary behaviours are largely associated with promoting physical form and function, bodybuilding athletes are graded solely on their appearance [4, 16]. The International Bodybuilding and Fitness Federation (IBFF) judging criteria for female competitors takes into account their hair and make-up; overall athletic development of the musculature; muscle proportion, symmetry, balance and shape; the condition of the skin and skin tone; and the athletes’ ability to present onstage with confidence [17]. There is added pressure on female bodybuilding athletes to look a certain way and to accept judgement on their physical appearance rather than physical performance. Due to this, female bodybuilding athletes (i.e., bikini, physique and figure athletes) may be one group who are at an increased risk for DE and EDs including substance abuse and engaging in extreme exercise and weight cutting regimes [16, 18]. Consistent with this, male bodybuilding athletes exhibit higher rates of body dissatisfaction and muscle dysmorphia [4], both of which are associated with DE and EDs. However, considerably less attention has been given to bodybuilding literature compared with other sports [16] and therefore further research is required.

Whilst research on DE and EDs in female and male athletes has increased over the last two decades, there remains a need to elucidate if, and to what extent, DE and EDs are prevalent in competitive female bodybuilding athletes. The use of validated questions such as The Female Athlete Screening Tools (FAST) provide valuable insight into DE and EDs in athletes. The questionnaire consists of 33 questions which provides insight into atypical exercise and eating behaviours that are synonymous with DE and EDs [19]. The questionnaire has been used extensively in research and is considered a reliable tool that possesses discriminative, concurrent and face validity [19,20,21]. Furthermore, the FAST questionnaire provides valuable insight into subclinical EDs [21] as well as a providing a single value from which a preoccupation with food, calories, body shape and body mass can be evaluated against (i.e. > 20) and deemed to be risk factors for EDs [22]. Furthermore, an understanding of the changes in characteristics such as body mass can support the knowledge gained from the questionnaire as large fluctuation in body mass and a desire to have a low body mass are noted as potential risk factors [23]. Whilst questionnaires are commonly used to gain insight into DE and EDs, the use of paper-based methods limits the reach, has a high distribution cost and has a low response rate. In contrast, online questionnaire through already established platforms allow for efficient and cheap distribution and can ensure that only fully completed questionnaires are retuned. Both methods are, however, limited by the response rate which typically ranged from ~ 30 to ~ 50% [24] and are influenced by the participant self-completing the questionnaire potentially giving rise to socially desirable results.

Therefore, the aim of the study was to investigate differences in eating attitudes, behaviours, and beliefs in female bodybuilding athletes and a non-athlete group using a web-based version of the FAST questionnaire. It was hypothesised that female body building athlete display greater tendency to engage in behaviours that are associated with DE.

Method

The study is reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines for cross-sectional studies [25]. An observational, cross-sectional design with participants divided into two groups: female bodybuilding athletes and female non-athletes. All data collected were used for analysis in the present study. Data collection took place from November 2017 to February 2018. The Bristol Online Survey (BOS) (https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/) was used to convert validated questionnaires into online questionnaires, which were distributed via social media platforms (Facebook and Instagram).

Participants

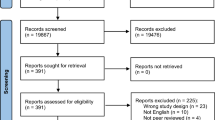

Eighty-two individuals provided their informed consent, and self-assigned as either ‘bodybuilding athlete’ (n = 42) or ‘non-athlete’ (n = 40). Seven participants were excluded due to a previously diagnosed ED (n = 3), incomplete questionnaire data (n = 2), and not meeting the group criteria (n = 2).

Participants were recruited using snowball sampling, whereby users shared the study information and questionnaires online with their social network. Eligible participants were female, 18–35 years old, and without a previously diagnosed ED. Participants self-assigned as either a ‘bodybuilding athlete’ or a ‘non-athlete’ and completed the respective questionnaire(s). Bodybuilding athletes must have trained for the sole purpose of developing one’s musculature for aesthetic purposes as well as having competed in ≥ 1 IBFF-affiliated bodybuilding show(s). Female bodybuilding consists of several categories, including bikini, wellness, physique, and figure, with each category subject to a different scoring criteria. In the present study, a “bodybuilding athlete” is an athlete that has competed in any category. Non-athletes completed ≤ 150 min of physical activity, exercise or sporting activity per week which is indicative of not meeting currently physical activity guidelines [26]. Individuals not meeting the above criteria, which was outlined in the participant information sheet, or those with incomplete data, were excluded the final analysis. All participants were informed of the benefits and risks associated with the study before providing written informed consent. Institutional ethics approval was granted by Manchester Metropolitan University ethics committee (No. 1555).

Procedures

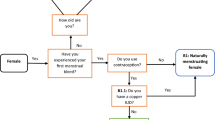

Eating attitudes, behaviours, and beliefs were assessed in both groups using the 26-item Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26). The EAT-26 is composed of a set of demographic questions, 26 eating attitude questions, 5 behavioural questions, and is a valid tool used to identify DE and EDs [27]. From the results, a total EAT-26 score as a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable (≥ 20 and ≤ 19) were determined. A cut-off score of ≥ 20 on the EAT-26 correctly classifies ~ 83.6% of individuals with anorexia nervosa [27]—but it is not a clinical diagnostic tool. Instead, the dichotomous cut-off is suggested to detect the incidence of subclinical EDs [22]. The bodybuilding athlete group also completed the FAST, which was modified to accommodate terminology used in bodybuilding training and competition; these questions can be found in Figs. 2, 3, 4 in the Results. The FAST has been validated as a suitable tool for detecting DE and EDs in female athletes [19]. Whilst the removal of some questions due to them being focussed on physical performance, completing 20 min of activity per day and being unable to compete, as well as altering the terminology used, might have impacted on the validity, this was deemed necessary to ensure the suitability with this population. The frequency distribution of the FAST was also included as an outcome for the bodybuilding athlete group. Due to the removal of some non-specific questions, results for the FAST questionnaire are reported as the frequency distribution for each criterion. This approach enabled appraisal without compromising the validity and reliability of the tool. The FAST results were grouped into three key domains in this study: dietary behaviours, training behaviours, and beliefs and perceptions.

Statistical analysis

Questionnaire data were exported from BOS to SPSS (Version 26.0 for Mac, SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY). The chi-squared (x2) test was used to examine the categorical EAT-26 scores (≥ 20 vs. ≤ 19) as well as response to each sub-question. Assumptions of normality were checked using the Shapiro–Wilk statistic with those variables violating this assumption assessed using the Mann–Whitney U statistic and those normally distributed assessed using an independent t-test. Continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD; and categorical data (e.g., frequency distribution on FAST results) are expressed as percentage of responses. Significance was set at 0.05.

Results

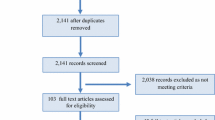

In total, 75 participants were included in data analysis, consisting of 37 bodybuilding athletes and 38 non-athletes. Participant characteristics and between-group differences are presented in Table 1. Total EAT-26 score was significantly higher in the bodybuilding group when compared to the non-athlete group (11.2 ± 9.8 cf. 22.3 ± 12.8 AU; − 3.894, P = 0.0001) with a significantly greater proportion of bodybuilding athletes considered ‘at risk’ of an ED (56.8% cf. 23.7%; χ2 = 8.54, P = 0.003); that is, scoring above 20. A greater proportion of bodybuilding athletes answered “yes” to all EAT-26 behavioural questions that asked about binge eating, self-induced vomiting, use of dieting pills, laxatives or diuretics, excessive exercising and extreme weight loss (Fig. 1), with significant differences observed for use of supplements, exercise for the purpose of losing weight and recording a large change in body mass (P > 0.05) when compare to non-athletes. There was a difference in vomiting to control weight and binge eating, though these did not reach statistical significance.

Analysis of the FAST data revealed a significant difference in the responses to all but one question regarding the dietary behaviours and implications on body composition (χ2 = 5.486 to 41.595, P = 0.139 to 0.0001) (Fig. 2). Collectively, the results indicate that a large proportion of female bodybuilding athletes weigh themselves regularly throughout the week and are concerned about their body fat. This is associated with more athletes manipulating their diet (i.e., avoiding eating or limiting specific macronutrients) or engaging with practices designed to keep their body mass low or reducing their body fat (Fig. 2).

The proportion of responses to questions regarding exercise, training and food intake are presented in Fig. 3. Results revealed significant differences in the response (χ2 = 11.757 to 47.649, P = 0.008 to 0.0001), with majority exercising or training to avoid increasing body mass and most participant altering their diet in relation to training (Fig. 3).

In relation to eating beliefs, a large proportion of participants believe that many female bodybuilding athletes have some form of DE (χ2 = 18.842, P = 0.0003) and that their perception differs from that of their friends when discussing thinness/fatness (χ2 = 11.895, P = 0.008). A large but non-significant proportion of female bodybuilding athletes also felt they “were not good at all” (χ2 = 6.000, P = 0.112), with few good qualities (χ2 = 14.842, P = 0.002), which might reflect the high quest for perfection (χ2 = 8.486, P = 0.014) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

This study sought to determine differences in eating attitudes, behaviours, and beliefs in female bodybuilding athletes and a non-athlete group. The key findings shows that female bodybuilders are at greater risk of EDs than female non-athletes, with a large proportion (56.8%) of bodybuilding athletes being categorised as at risk of an ED [22, 28]. This might may, in part, be a reflection of the observations that shows DE behaviours are more prevalent in athletes when compared to non-athlete groups [7, 15]. Furthermore, our results support the notion that athletes who participate in sports that emphasise aesthetics present with DE behaviours and a higher risk of EDs [5, 7, 13, 15] despite similarities in the anthropometric characteristics and a BMI indicative of being considered healthy.

Self-reported ‘highest’ and ‘optimal’ body mass differed by approximately 10 kg between groups, with ~ 25% of the bodybuilding athlete group reporting losses of 9 kg over a 6-month period. Whilst BMI was not different at the time of data collection, it is likely that the change in BMI is greater in female bodybuilders due to a so-called “yo-yo effect” in body mass around competition preparations [29]. Periods of dieting and the associated fluctuation in body mass is noted as a risk factor for developing EDs [23]. For example, immediately following competition, female bodybuilding athletes may alter their dietary behaviour by adopting a more ‘relaxed’ manner, with Mitchell et al. [30] reporting greater carbohydrate intake 4 weeks after competition, which may be perceived as a ‘binge’ [31]. Less severe dieting strategies to rapidly reduce body mass, for example, in the build-up to competition, could reduce the risk of DE and EDs, though this warrants further research.

Eighty-one percent of athletes stated they believe most female bodybuilding athletes have some form of DE habits. Whilst this suggests that female bodybuilding athletes are likely to be a greater risk of EDs, it is important to note that athletes may demonstrate DE behaviours in an attempt to conform to the ‘sporting ideal’, displaying dedication and a “do what it takes to win” attitude [32]. Furthermore, engaging in DE behaviours might also reflect participants beliefs and attitudes toward themselves. Female bodybuilding sports are judged and graded based on specific criteria including muscle definition and symmetry [4], which might promote muscle dissatisfaction and issues around body image that have been associated with EDs in male bodybuilders [4]. In this study, most athletes disagreed when posed with the statement ‘I feel that I have a lot of good qualities’ and just under 60% of athletes reported they feel ‘fat’ despite friends stating they are ‘thin’. These findings might reflect the desire for perfection in achieving symmetry and muscle definition that, in males, is associated with muscle dysmorphia and can lead to the development of DE and EDs [4]. Whilst such findings are likely to be important risk factors for the development of DE and EDs, it is worth highlighting that these findings might have been similar in our non-athlete group who did not complete the FAST questionnaire. That said, previous work comparing those competing in aesthetic and non-aesthetic sports indicated that participating in an aesthetic sport significant decreased perceptions of body image (− 2.757 AU, P < 0.001) [33, 34].

It is possible that other intrinsic and extrinsic factors, which are beyond the scope of this study but have been previously seen that could impact athlete’s perception of themselves, such as; low self-esteem, desire for control, hurtful relationships or role models and satisfaction with body shape and physical appearance [35]. Further research should seek to determine the exact reasons why bodybuilding athletes have negative beliefs and attitudes towards themselves or if it is the case that those who exhibit symptoms associated with EDs and DE are more likely to participate in bodybuilding.

The female bodybuilding athletes in this study reported several strategies to reduce and or control their body mass that were not reported the same extent in the non-athletes group. For example, a greater proportion (27.0% cf. 13.2%) of athletes indicated that they have purposely made themselves vomit; have taken some form of supplement; and exercised for the purpose of weight loss and/or control. Athletes also aim to control body mass by manipulating their nutrition intake. Whilst reducing carbohydrate intake has been noted previously [28], the findings that athletes limit their protein intake to avoid gaining weight is interesting given the role protein plays in muscle protein synthesis [36] and in the preservation of lean mass under hypocaloric conditions [37]. This suggests there is a need for improved education on macronutrient intake as well as total energy intake, particularly considering the risk of relative energy deficiency in female athletes [11].

Another strategy to reduce or maintain body mass was the intake of diet pills, laxatives, herbal supplements or diuretics that majority of athletes acknowledge might be deemed unhealthy (Fig. 3). Whilst the exact nutritional supplements were not explored in this study, these findings are consistent with previous research that has noted bodybuilders (males and/or females) typically consume supplemental protein, vitamins [31, 38] and, in some cases, anabolic steroids [16]. Finally, athletes also demonstrated a dependency on exercise as a means of weight loss or maintenance, which has been observed previously [5, 39]. The reliance on exercise is demonstrated by ~ 70% of athletes reporting that they would worry about gaining weight should they not be able to exercise and is indicative of eating psychopathology. Furthermore, a large proportion of participants (75.6%) stated they would sometimes or frequently exercise on rest, which reaffirms the importance of exercise in this population. Future research might seek to determine the reasons behind these behaviours as well as determining the intended and unintended consequences of these practices.

This study provided insight on DE and EDs in female bodybuilding athletes compared to a non-athlete group despite similar baseline characteristics. There are, however, several limitations that are worthy of discussion. First, this study is limited to a relatively small sample that limits the extrapolation of these findings to other populations and when considering various stages of the competitive season (e.g., pre-competition, in-competition and post-competition). Second, athletes self-selected the group on the online survey which might have resulted in group misplacement. Thirdly, we were unable to provide an overall score for the FAST questionnaire as some questions that did not relate to our population were removed, thus meaning the reader unable to compare a total score to other studies. Direct comparison of individual questions is possible. Further, the use of an online survey might have resulted in under-reporting of psychopathological risk due the potential of reporting bias associated with normalisation of practices, stigma and acceptance of a potential issue [40]. As stature and body mass were self-reported, it is also possible that the validity of these measures is compromised, though from our experience and the previous literature [41] the difference between measured and reported are generally trivial (stature, ES = − 0.05; body mass, ES 0.104). Finally, clinical diagnosis of EDs was not the purpose of this study and tools such as EAT-26 and FAST are not the ‘gold standard’ for determining clinical risk, whereby an interview should be favoured [7, 15].

Conclusion

The results of this study show that there is a significantly higher risk of EDs and DE behaviour among female bodybuilding athletes than non-athlete females. Female bodybuilding athletes also had high body mass preoccupation; engaged in exercise for the purpose of reducing or maintaining body mass; and demonstrated perceptions of themselves and others reflective of a higher risk of DE and EDs. These results do, however, highlight the importance of educating both key stakeholders in the fitness and bodybuilding industries as well as athletes and coaches on the risk factors and behaviours associated with DE and EDs. In cases where those working with female body builders suspect DE or EDs, support should be sought from relevant services as well as clinical dietician and psychologist [11, 42]. From a policy standpoint, these findings combined with the pre-existing literature, might encourage the IBBF to 1) Produce guidelines on healthy strategies to increase leanness safely as has been the focus in other athletes (e.g., jockeys), 2) Provide information to athletes and coaches on how to spot someone who is at risk of DE and EDs, and 3) Offer guidance and support to athletes who exhibit DE and EDs, signposting to the relevant support services (e.g., Beat) and health professionals (e.g., clinical dietitians) available.

Availability of data

Available upon request.

References

Downward P, Rasciute S (2015) Exploring the covariates of sport participation for health: an analysis of male and females in England. J Sports Sci 33(1):67–76

Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR (2013) A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-98

De Oliveria Coelho GM, de Farias MLF, de Menonça LMC et al (2013) The prevalence of disordered eating and possible health consequences in adolescent female tennis players from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Appetite 64:39–47

Devrim A, Bilgic P, Hongu N (2018) Is there any relationship between body image perception, eating disorders, and muscle dysmorphic disorders in male bodybuilders. Am J Mens Health 12(5):1746–1758

Kong P, Harris L (2014) The sporting body: body image and eating disorder symptomatology among female athletes from leanness focussed and non-leanness focused sports. J Psychol 149(2):141–160

Torstveit MK, Rosenvinge JH, Sundgot-Borgen J (2008) Prevalence of eating disorders and the predictive power of risk models in female elite athletes: a controlled study. Scand J Med Sci Sport 18(1):108–118

Sundgot-Borgen J, Torstveit M (2004) Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clin J Sports Med 14(1):25–32

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. Psychiatric Association, Washington

Hausenblas HA, Carron AV (1999) Eating disorder indices and athletes: an integration. J Sport Exerc Psychol 21(3):230–258

Galasso L, Montaruli A, Jankowski KS et al (2020) Binge eating disorders: what is the role of physical activity associated with dietary and psychological treatment. Nutrients 12(12):3622

Desbrow B, Burd NA, Tarnopolsky M, Moore DR, Elliott-Sale KJ (2019) Nutrition for special populations: young, female, and master athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 29(2):220–227

Nattiv A, Loucks AB, Manore MM et al (2007) American College of Sport Medicine position stand. The female athlete triad. Med Sci Sport Exerc 39(10):1867–1882

Byrne S, McLean N (2001) Eating disorders in athletes: a review of the literature. J Sci Med Sport 4(2):145–159

Krebs PA, Dennison CR, Kellar K, Lucas J (2019) Gender differences in eating disorder risk among NCAA division I cross country and track student-athletes. J Sport Med. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/503587

Martinsen M, Sundgot-Borgen J (2013) High prevalence of eating disorders among adolescent elite athletes than controls. Med Sci Sport Exerc 45(6):1188–1197

Goldfield GS (2009) Body image, disordered eating and anabolic steroid use in female bodybuilders. Eat Disord 17:200–210

International bodybuilding and fitness federation (2019). http://ifbb.com/wp-content/uploads/RULES/Womens-Bodybuilding-Rules-2019.pdf

Scott A (2011) Pumping up the pomp: an exploration of femininity and female bodybuilding. Explor Anthropol 11(1):70–88

McNulty KY, Adams CH, Anderson JM, Affenito SG (2001) Development and validation of a screening tool to identify eating disorders in female athletes. J Am Diet Assoc 101(8):886–892

Affenito SG, Yeager KA, Rosman JL et al (2001) Development and validation of a screening tool to identify eating disorders in the female athletes. J Am Diet Assoc 101(8):886–892

Knapp J, Aerni G, Anderson J (2014) Eating disorders in female athletes: use of screening tools. Curr Sports Med Rep 12(4):214–218

Beals KA, Manore MM (1994) The prevalence and consequences of subclinical eating disorders in female athletes. Int J Sports Nutr 4(2):175–195

Sundgot-Borgen J (1994) Risk and trigger factors for the development of eating disorders in female elite athletes. Med Sci Sport Exerc 26(4):414–419

Greenlaw C, Brown-Welty S (2009) A comparison of web-based and paper-based survey methods. Eval Rev 33(5):464–480

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al (2007) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 147(8):573–577

Department of Health and Social Care (2019) UK chief medical officers’ physical activity guidelines. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf

Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE (1982) The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psych Med 12(4):871–878

Probert AP, Palmer F, Leberman S (2007) The fine line: an insight into ‘risky’ practices of male and female competitive bodybuilders. Ann Leis Res 10(3–4):272–290

Amigo I, Fernández-Rogríguez C (2007) Effects of diets and their role in weight control. Psych Health Med 12(3):321–327

Mitchell L, Slater G, Hackett D, Johnson N, O’Connor H (2018) Physiological implications of preparing or natural male bodybuilding competitive. Eur J Sport Sci 18(5):619–629

Andersen RE, Barlett SJ, Morgan GD, Bownell KD (1995) Weight loss, psychological, and nutritional patterns in competitive male body builders. Int J Eat Disord 18(1):49–57

Suffolk MT (2014) Competitive bodybuilding: positive deviance, body image pathology, or modern day competitive sport. J Clin Sport Psychol 8(4):339–356

Kantanista A, Glapa A, Banio A et al (2018) Body image of highly trained female athletes engaged in different types of sport. Biomed Res Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6835751

Reinking MF, Alexander LE (2005) Prevalence of disordered-eating behaviours in undergraduate female collegiate athletes and nonathletes. J Athl Train 40(1):47–51

Arthur-Cameselle J, Quatromoni PA (2010) Factors related to the onset of eating disorders reported by female collegiate athletes. Sport Psychol 25:1–17

Morton RW, McGlory C, Phillips SM (2015) Nutritional interventions to augment resistance training-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Front Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2015.00245

Mettler S, Mitchell N, Tipton KD (2010) Increased protein intake reduces lean body mass loss during weight loss in athletes. Med Sci Sport Exerc 42(2):326–337

Chappell AJ, Simper T, Barker ME (2019) Nutritional strategies of high level natural bodybuilders during competitive preparation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-018-0209-z

Hale BD, Diehl D, Weaver K, Briggs M (2013) Exercise dependence and muscle dysmorphia in novice and experienced female bodybuilders. J Behav Addict 2(4):244–248

Plateau CR, Arcelus J, Leung N, Meyer C (2017) Female athlete experience of seeking in receiving treatment for an eating disorder. Eat Disord 25(3):273–277

Gokler ME, Bugrul N, San AO, Metintas S (2018) The validity of self-reported vs measured body weight and height and the effect of self-perception. Arch Med Sci. 14(1):174–181

De Oliveria Coelho GM, da Silva Gomes AI, Riberio BG, de Abreu SE (2014) Prevention of eating disorders in female athletes. Open Access J Sports Med 12(5):105–113

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by Manchester Metropolitan University ethics committee (Ref No. 1555). This study was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Money-Taylor, E., Dobbin, N., Gregg, R. et al. Differences in attitudes, behaviours and beliefs towards eating between female bodybuilding athletes and non-athletes, and the implications for eating disorders and disordered eating. Sport Sci Health 18, 67–74 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-021-00775-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-021-00775-2