Abstract

Person-organization (PO) fit is broadly defined as the compatibility between an individual and their employing organization that occurs when the characteristics of the two entities are well matched. It is related to higher levels of organizational commitment, job satisfaction, job retention, organizational citizenship behaviours, and job performance. In recent years, there has been a significant and hastening increase in the number of journal articles published in which person-organization fit is a major feature of the study. This study documents the historical and contemporary nature of this field using bibliometric methods to provide an overview of PO fit research and to analyse contemporary trends. After screening, 887 refereed journal articles were surfaced in the Scopus database that featured PO fit. Descriptively, this study identifies leading journal articles, authors, countries, and collaborative networks. Analytically, the paper identifies and discusses major and emerging research themes. These include an increase in studies exploring PO fit and its impact on employee engagement during their employment. Other contemporary themes include an increasing interest in ethical issues related to PO fit and the interaction of PO and person-job fit. These three topics are critically discussed. Conversely, the analysis shows a lessening of the occurrence of PO fit studies focusing on the early employment phases of recruitment, selection, and socialization. The paper concludes with a discussion of the ways in which PO fit research is changing, the positive skew in PO fit research, and the limitations of this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years there has been a significant uplift in the number of peer-reviewed journal articles that have been published on the topic of person-organization (PO) fit (De Cooman et al. 2019). Whereas in the 1980 and 1990 s only a handful of papers were being published each year on the topic, more than 50 journal articles have been published in each of the last five years, with the trend rising. Moreover, there is a shift in this literature with less concern about organizational entry phases of employment and more focus on the engagement of employed workers. It is advantageous to document such changes to help current and prospective PO fit researchers to appraise the nature of these trends.

Bibliometric analysis is an excellent tool for documenting the nature of a literature and the trends and trajectories within it (Block and Fisch 2020; Linnenluecke et al. 2019). This is especially important in fields like PO fit that are rapidly evolving. Bibliometric analysis can provide a primer for prospective PO fit researchers to (1) highlight the core texts, outlets, and themes so that a targeted familiarization might be achieved, and (2) identify the contemporary themes that PO fit researchers are addressing. These are the goals of this study.

This paper adopts the traditional structure and styles used in papers presenting bibliometric studies (e.g., Bühren et al. 2022; Simao et al. 2021; Xie et al. 2020). It begins with a brief literature review in which the field of study, PO fit, is defined, its importance shown, and the research goals outlined. The method section explains how the systematic search of the PO fit literature was conducted and decisions made. The results section is split into two halves. The first offers an overview of the PO fit literature through bibliometric analysis, while the second section looks at contemporary trends. The discussion draws out overarching themes in PO fit research and considers limits to the generalizability of the study.

2 Person-Organization Fit

PO fit is defined as the compatibility or congruence between organizations and their employees on characteristics that are important to both (Chatman 1989; Kristof 1996; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005). PO fit is a type of person-environment (PE) fit; the latter being the superordinate form of fit under which other types of fit such as PO fit, person-job (PJ), person-vocation (PV), person-supervisor (PS), and person-group (PG) fit are located.

PO fit is formed by the interaction of salient aspects of the employee (the ‘person’) and their employer (the ‘organization’) (Chatman 1989; Kristof 1996; Vogel et al. 2016). PO interactions have mainly been conceptualized in two forms: supplementary or complementary. Supplementary fit assesses the similarity in characteristics (typically values, goals, personality) of the person and the organization. Value congruence is the form of supplementary PO fit most commonly studied (Edwards and Cable 2009). So, value congruence studies examine whether the values of the employee are similar to those of the organization and the impact that this has for the employee, the organization, or both. Complementary fit assesses the extent to which an aspect of one of the two entities fits into the other. This type of fit is commonly divided into needs-supplies (NS) and demand-abilities (DA) forms. NS fit occurs when the organization supplies what the individual needs and DA fit occurs when the individual has the knowledge, skills, and abilities the organization demands of them (Kristof 1996).

Conceptualizing PO fit is further complicated by actual and perceived forms (Kristof-Brown and Billsberry 2013). Actual PO fit refers to the objective measurement of person and organization variables so that PO fit is calculated externally to the individual (Edwards 2008). Perceived PO fit refers an employee’s psychological construction of their own PO fit. These forms of PO fit intertwine with issues of measurement. Perceived PO fit is typically measured with direct measures, which ask employees to say how well they fit an organization. Actual forms of PO fit are typically measured with indirect measures that separately capture person and organization variables followed by the calculation of fit. Edwards (2008) argues that perceived fit captures an individual’s personal construct of PO fit, whereas actual forms are more distant to the individual’s sense of fit.

Edwards et al. (2006) further deconstruct the measurement of PO fit into atomic, molar, and molecular forms. Atomic measurement splits out the person and organization variables to calculate fit, typically with polynomial regression and response surface analysis, so it tends to be associated with actual and indirect conceptualizations. Molar measurement asks employees to assess their similarity to an organization, while molecular measurement asks employees to assess their discrepancies to an organization. These methods tend to be associated with direct and perceived conceptualizations, and naturally molar measurement is directly connected to the study of PO fit and molecular to PO misfit, although many studies of perceived employee misfit use molar measures (e.g., Deng et al. 2015; Zubielevitch et al. 2021).

There is considerable variation in the currency of fit. Although values have been used most commonly, many other constructs have been used in PO fit conceptualizations including personality, norms, goals, culture, motivation, perceptions, career orientation, age and other demographic variables, proactivity, preferred and actual job complexity, problem-solving style, meaningfulness of work, political ideologies, work-life integration and segmentation, and preference for email communication. This variety demonstrates that many atomistic, indirect, and actual PO fit studies are using PO fit methodologies to compare the interaction of two sets of variables of interest to researchers rather than looking at PO fit as a construct in people’s heads, which tends to be the province of perceived, molar, molecular, and direct approaches to PO fit (Edwards 2008).

3 Why is Person-Organization Fit important?

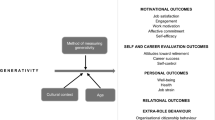

Understanding PO fit helps researchers predict individual and organizational outcomes (Kristof 1996) particularly affective, performance, and turnover outcomes for the individual and homogeneity outcomes for organizations. Higher levels of PO fit have been shown to be associated with higher levels of job satisfaction, organizational commitment, employee retention, organizational citizenship behaviours, and task performance (Das 2022; Hoffman and Woehr 2006; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Verquer et al. 2003). For the organization, the benefits of higher levels of PO fit are much less clear. Schneider (1987) argues that higher levels of PO fit lead to higher levels of employee homogeneity, which was demonstrated in a subsequent study (Schneider et al. 1998). This homogeneity is thought to be potentially damaging to organizations as it has been argued that it makes them less able to change, less suited to their environments, and less creative. However, O’Reilly et al. (1998) demonstrated that higher levels of PO fit, operationalized through person-group fit, reduce conflict and promote conditions for creativity. In summary, PO fit studies have shown that higher levels of PO fit are good for the psychology of the individual (Follmer et al. 2018; Lamiani et al. 2018; Vogel et al. 2016), but there is a lot of debate as to whether higher levels of PO fit benefit the organization.

4 Research Objectives

It has been a few years since the last comprehensive reviews of the PO fit literature (e.g., Edwards 2008; Kristof-Brown and Billsberry 2013; Kristof-Brown and Guay 2011; Verquer et al. 2003) were published. Since then, the occurrence of empirical PO fit studies published per year has accelerated making this a suitable moment to document the new wave of research and to surface contemporary research interests and how they have changed (De Cooman et al. 2019). Such a review acts as a guide for anyone wishing to undertake PO fit research by identifying foundational papers, the locations where PO fit research is published, the key researchers and their collaborative networks, and the main themes in PO fit research. So, the first series of research objectives (RO) for this review relates to mapping PO fit research since the establishment of PO fit nomenclature.

RO1: To identify publication trends in PO fit research (Sect. 6.1).

RO2: To identify leading countries in PO fit research (Sect. 6.2).

RO3: To identify the most prolific and most cited peer-reviewed journals publishing PO fit research (Sect. 6.3).

RO4: To identify PO fit researcher networks (Sect. 6.4).

RO5: To identify the most cited PO fit journal articles (Sect. 6.5).

RO6: To identify the domains, functions, outcomes, issues, and processes that PO fit studies address (Sect. 6.6).

The second series of objectives relates to the contemporary landscape of PO fit research. Anyone coming to the field now will want to know what are the current trends that PO fit researchers are interested in and how the field is different now. One of the challenges in coming new to a field is that focusing on the seminal articles and most cited debates socializes the new researcher to old debates rather than new ones. So, while it is important to have a thorough grounding in the key issues of the field, this must be tempered by an appreciation of the new and the current. So, the second series of research objectives for this review relates to a mapping of contemporary PO fit research.

RO7: To identify contemporary trends in PO fit research (Sect. 7.1).

RO8: To critically review leading contemporary trends avenues in PO fit research (Sect. 7.2–7.4).

RO9: To identify avenues for future PO fit research (Sect. 7.2–7.4).

5 Method

The primary purpose of this study is to map research that has been published on the topic of PO fit in peer-reviewed academic journals. To this end, we conducted a systematic review of the PO fit literature searching for empirical and review studies on the topic. We adopted a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) approach and followed the bibliometric analysis guidelines of van Oorschot et al. (2018). Peer-review status of a journal was established by checking the journal’s record in the researchers’ library or the journal’s website. We only included papers written in English. No date limits were set for the initial search so this study could fully chart the field.

The database used, Scopus, contains over 60 million documents dating from 1865. The earliest PO fit paper was published in 1982 and the search was run on 9 June 2021. So, the effective period this survey covers is 1982 to early-June 2021. To aid interpretation, Fig. 1, which displays the annual number of papers published on PO fit, does not include the partial data for 2021. To show contemporary themes in PO fit research, Fig. 2 focuses on the period January 2018 to early June 2021. To show trends in these contemporary themes, Fig. 3 covers the period 2015–2020 (2021 is excluded because full-year data was unavailable and partial data would distort the chart).

5.1 Search methodology

5.1.1 Inclusion criteria

We searched for the phrases ‘person-organization fit’, ‘employee-organization fit’, ‘needs-supplies fit’, ‘demands-abilities fit’, ‘organizational fit’, along with alternative spellings (e.g., ‘organisation’ as well as ‘organization’), abbreviations (e.g., PO fit, P-O fit), and different types of dashes (hyphens, ‘en’ dashes, ‘em’ dashes, and spaces). The logical operator OR was used between each phrase meaning that a journal article only had to return one of these phrases in the title, abstract, or keywords to be found. The syntax can be viewed in the Appendix.

5.1.2 Exclusion criteria

As initial pilot work suggested that there were no alternative uses of the phrase ‘person-organization fit’ that would compromise the results, no exclusion criteria were added to the search. However, the phrases ‘organizational fit’ and ‘organisational fit’ are known to have dual use. They can be used to refer to person-organization fit, our area of interest, or they can refer to the mutual fit of organizations (i.e., organization-organization fit), typically during or after mergers and acquisitions (e.g., Cartwright and Schoenberg 2006; Weber 2015), which is not relevant to this review. As we needed to keep these phrases in the search for completeness, the abstracts of surfaced papers were examined to remove cases of organization-organization fit. In effect, they were manually filtered out.

5.1.3 Databases searched

This search was limited to the Scopus database. Scopus has been shown to have a more complete coverage of business, management, and psychology journals than competing databases (Mingers and Lipitakis 2010) and tends to return more hits than Web of Science although there is considerable overlap (Martín-Martín et al. 2021). The natural alternatives are Web of Science and Google Scholar. Martin-Martin et al. (2021) report the overlap with Scopus to be 83% for Web of Science and 90% for Google Scholar.

5.2 Search results

Adopting the search criteria mentioned above, this search for papers initially yielded 1119 papers. A summary of the results of the filtering process is shown in Fig. 1. This cleaning was done sequentially and eliminated 232 (20.7%) papers resulting in a final database size of 887 peer-reviewed journal articles.

5.3 Software and techniques

Bibliometric analyses were run in VOSviewer version 1.6.15 (Van Eck and Waltman 2010).

6 Mapping PO fit research

6.1 Publication trends

The number of published PO fit articles by year is shown in Fig. 2. This shows the rapid growth of interest in PO fit. The graph shows that PO fit research began in 1982 with Matteson and Ivancevich (1982) who used the phrase ‘individual and organizational fit’ in their title. But it was the influential theoretical paper, Chatman (1989), and the subsequent integrative review, Kristof (1996), that cemented the language of PO fit. Prior to 1982, issues related to PO fit had been discussed in the literature (e.g., Thorndike 1950; Tom 1971), but it was only from this time that the nomenclature caught hold.

Until 2000, only a handful of journal articles were being published every year. The rapid growth began from this time. Between 2000 and 2010, the numbers of papers published per year rose from approximately 5 to approximately 25, a five-fold increase. From 2011 to 2020, the annual number rose from 42 to 117 making PO fit a significant topic in the applied psychology and management domains, and as one showing significant year-on-year momentum.

6.2 Leading countries in PO fit research

Table 1 shows the geographic distribution of authors by affiliation of journal articles on PO fit. Each country that appears in the affiliations is credited with that paper. Hence, a single paper may be counted several times. For example, there are 367 journal articles featuring at least one author affiliated to a university or organization located in the United States. The table illustrates how strongly this field is dominated by authors located in the United States (41.38%), with only authors located in the United Kingdom, China, Australia, South Korea, Taiwan, and Canada appearing on 5% or more of papers.

6.3 Leading journals

One benefit of bibliometric analysis is that it can show prospective researchers where papers on the topic are published and which journals publishing papers in the field have the most impact. Accordingly, we have listed the leading journals for PO fit research in terms of the number of papers published (Table 2) and Scopus citations per article (Table 3). We sorted the database of 887 articles by ‘Source Title’ and counted the number of articles published in each journal, the number of citations recorded in Scopus, and then divided one by the other to calculate the citations per article. We then placed the various journals in the order of the number of articles published in each journal (Table 2) and the highest number of citations per article (Table 3). These tables show where PO fit research is typically published (Table 2) and where the most impactful PO fit research is published (Table 3).

Table 2 shows that there are a broad range of journals regularly publishing journal articles on PO fit. Reinforcing the notion that PO fit is now a mainstream subject, these include applied psychology journals, human resource management journals, business ethics journals, and some public administration journals. Table 3 highlights the citation-gathering impact of review and theory type papers that are published early in the genesis of the domain in top-ranked journals.

6.4 Author analysis

Bibliometric analysis allows researcher networks to be mapped (Nakagawa et al. 2018). This type of analysis has the benefit of revealing the cross-fertilization of ideas and perspectives and the inclusiveness of the scholarly community. It was therefore something of a surprise, and somewhat ironic given the nature of the topic, to discover that researchers in this scholarly community are largely separated from each other in terms of the co-authorship of journal papers. There are several established groups of scholars, such as Tim Judge and Dan Cable, but even setting the thresholds as low as the software permits surfaces very few co-authoring links between clusters of authors (see Fig. 3).

6.5 Citation analysis

Surfacing a list of the most cited journal articles in the field provides guidance to prospective scholars wanting to conduct PO fit research on the key texts that reviewers will expect them to know. Being the most cited, they are likely to be relatively old and prospective PO fit scholars need to ensure they develop a similar understanding of contemporary issues, but nevertheless, such a list provides an excellent starting point. To double-check for completeness, we also ran the search in Google Scholar. It revealed five papers that have received more than 1000 Google Scholar citations that would have made their way onto our list had Scopus surfaced them. They are Chatman (1989; 3567 Google Scholar citations), Chatman (1991; 3569 Google Scholar citations), O’Reilly et al. (1991; 6743 Google Scholar citations), Schneider (1987; 2579 Scopus citations/6443 Google Scholar citations), and Schneider et al. (1995; 760 Scopus citations/1979 Google Scholar citations). The first three are not listed in Scopus, possibly because the PDFs on journal websites are in an unreadable form. The latter two did not surface as they use the language of Attraction-Selection-Attrition, or ASA, instead of PO fit.

A list of the most highly cited articles in PO fit research matching our criteria in Scopus can be found in Table 4. The top two articles, which have each attracted over 2,200 citations on Scopus (Google Scholar citations: Kristof (1996), 6187; Kristof et al. (2005), 5526), offer comprehensive reviews of the field. The rest of the top ten contain two systematic reviews of various aspects of PO fit (i.e., Chapman et al. 2005; Verquer et al. 2003) and all bar one of the remaining ones focus on PO fit in the context of recruitment and selection, which was a primary driver in the early years of PO fit research. The exception is a paper exploring how PO fit influences organizational citizenship behaviour in a personal selling context (i.e., Netemeyer et al. 1997). In summary, the ten most cited papers that include PO fit in the title, abstract, or keywords have PO fit as their primary focus. This implies that PO fit is a major area of research in its own right and not ancillary to other topics.

6.6 Keyword co-occurrence

Analysis of keywords provides insight into the domains, functions, outcomes, issues, and processes that PO fit studies address. They represent the primary topics that authors believe their papers are about. Keyword co-occurrence analysis looks for patterns across studies to produce a clustering of terms. To explore these patterns within PO fit research, we removed the keyword ‘person-organization fit’ and its variants as these are circular and confound the analysis. Figure 4 shows how the remaining keywords in the 887 papers are networked together. It covers the period 1982 to early June 2021. The size of the text captures the relative strength of keywords. The colour captures the average publication date of the journal articles using each keyword: lighter shades denote more recent average publication dates. The colours depicting the average age for keywords can be seen in the legend in the bottom right-hand corner of the diagram. The network diagram has been rotated so that younger average ages appear at the top and to the left.

Themes in PO fit research: Keyword analysis, 1982–2021.

Note Colours indicate the average publication date of the journal articles using each keyword. Although the figure is limited to papers published between 1982 and 2021, VOSviewer produces a legend with 10-year intervals that extend before 1982. No papers have been included in this sample dated before 1982

Looking across the keywords co-occurrence commonly appearing early in the age-range, job satisfaction, commitment, recruitment, and types of fit dominate the clusters. These strongly reflect the focus of early work on PO fit that sought some construct validity by establishing the association of PO fit with outcomes like job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, organizational citizenship behaviour and such like (Verquer et al. 2003). There was also a focus on defining PO fit, which was described as an elusive construct (Rynes and Gerhart 1990) and how PO fit relates to other forms of fit (Edwards and Billsberry 2010: Jansen and Kristof-Brown 2006). Recruitment is the other major cluster, representing the focus on recruitment, selection, and socialization in early PO fit studies (e.g., Cable and Judge 1996, 1997).

7 Charting contemporary Trends in PO fit research

7.1 Contemporary Trends in PO fit research

In this section, we use bibliometric analysis to look at the direction in which PO fit research is heading. By focusing on the last three years, current areas of interest and contemporary trends can be identified especially when compared to the overall configurations of PO fit research. From the start of 2018 to the time of the search (early June 2021), 333 peer-reviewed journal articles on PO fit were surfaced by Scopus; 310 in print and 23 in-press. As noted above, Fig. 5 gives an indication of the current themes in PO fit research. It covers the period 2018 to early June 2021.

Figure 6. contains keyword analysis for the period 2015–2020 (2021 was excluded as it was not a full year of data). This shows that contemporary themes in PO fit have changed significantly. Having established the nomological network of PO fit, its relationships to other forms of fit, and its influence in recruitment, PO fit researchers have moved on to other topics. PO fit research has largely moved away from studies exploring organizational entry and moved to studies of employees’ fit during their employment particularly focusing on their engagement (e.g., Lv and Xu 2018), employees’ interaction with their jobs (e.g., Straatmann et al. 2020), and explorations of the ethical aspects of the construct (e.g., Kerse 2021). These are the three emerging areas of interest showing rapid increase having previously only been included occasionally in authors’ keywords. These contemporary themes are discussed in more depth the following subsections. Organizational commitment also demonstrated growth in 2020, but we excluded this theme from discussion in the next section because it is an enduring theme in PO fit research, rather than a newly emerging one as well as being closely related to engagement.

7.2 Contemporary theme 1: Engagement

Although PO fit researchers have long been interested in the relationship of PO fit and its effects on employee perceptions or behaviours, it is only relatively recently that employee engagement (EE) has emerged as a focus for this work. Researchers (e.g., Chawla 2020; Hicklenton et al. 2019; Kao et al. 2021; Lv and Xu 2018; Memon et al. 2018; Rawshdeh et al. 2019; Sekhar et al. 2018) have asked whether increasing employees’ PO fit increases their EE, leading to stronger intentions to stay, more promotive voice behaviours, (i.e., making suggestions for issues that may improve the work unit), more internal and external organizational citizenship behaviours (OCBs), perceived need satisfaction, and better job performance. Generally, the answers are yes, though the increase in EE varies. Memon et al. (2018) found that PO fit predicts EE, which is negatively related to intention to leave. Kao et al. (2021) found that PO fit strengthens the direct effect of EE on promotive voice behaviour (as well as the indirect effect of job autonomy on promotive voice behaviour through EE). PO fit has been found to partially mediate the positive relationship between employer branding and EE (Chawla 2020) and socially responsible HRM practices and EE (Rawshdeh et al. 2019). Flexible HRM makes the employee more ‘organization fit’ and more engaged for their respective job, which in turn improves their job performance (Sekhar et al. 2018). Hicklenton et al.(2019) looked at whether green-person-organization fit (GPO fit; the extent to which an organization’s commitment to pro-environmental outcomes reflects its employees’ environmental values) predicts employees’ intrinsic need satisfaction and EE. Echoing the effect of PO fit on employee ethics, GPO fit predicted intrinsic need satisfaction and EE more strongly for employees with strong ecocentric values than those with weak ecocentric values, as one might expect.

Studies have explored how PO fit mediates the effects of factors like spirituality and employer branding on EE. Iqbal et al. (2020) studied nurses in Indonesian public hospitals and showed that PO fit acts as a mechanism through which workplace spirituality affects nurse engagement. Similarly, PO fit partially mediates the effect on EE of employer branding (Chawla 2020), socially responsible HRM (Iqbal et al. 2020), and co-worker support and organizational commitment (Priyadarshi and Premchandran 2018). Rai and Nandy (2021) found that employer branding and employee retention are sequentially mediated by both PO fit and organizational identification. Mostafa and Andrews (2018) found that PO fit serves as a mechanism for EE in senior public managers in three continental European countries: France, Germany, and the Netherlands. Having an internal locus of control (ILC) strengthens the effect of autonomy on these managers’ EE. However, having an ILC actually weakens the effect of a shared organizational vision on EE. Social exchange theory (SET) has been used to explain perceived failures in the employer-employee relationship, such as psychological contract breaches (PCB). SET underpinned a study of 255 employees in China looking at the effects of PCB, PO fit, and a high-performance work system (HPWS) on EE. Results revealed that PCB negatively affects EE, and PO fit partially mediates this relationship. High levels of perceived HPWS aggravate (not buffer) the negative effect of PCB on EE and PO fit. In addition, the interaction of HPWS and PCB on EE is mediated by PO fit.

The authors of PO fit and EE studies acknowledge that future research should incorporate additional variables to better reflect complex organizational realities. Morrow and Brough (2019) recommend looking at component variables of superordinate constructs like person-environment fit and parallel constructs such as PV, PG, and PS fit alongside PO fit to develop a deeper understanding of the relationship between PO fit and EE. Kao et al.’s (2021) results reinforce earlier findings that promotive and prohibitive voice behaviours are different constructs by showing that PO fit influences them differently. Similarly, Chawla (2020) suggests that future studies should address potential negative effects, such as whether organizations who are unable to keep their brand promises create PCB. By definition, studies of PO fit and EE investigate current employees, not job candidates. Nevertheless, some authors (e.g., Chawla 2020; Morrow and Brough 2019) recommend that future researchers try to see how the positive effects of the PO fit/EE relationship could help organizations choose future employees or socialize new ones.

7.3 Contemporary theme 2: the intersection of PO and PJ Fit

An enduring feature of PO fit research has been how PO fit relates to other forms of fit. It is generally thought to be subordinate to PE fit, but the relationship of PO fit to PJ, PS, PG, PV, and other types of fit is unclear (Guan et al. 2021). Jansen and Kristof-Brown (2006) proposed a multidimensional theory of fit in which five different types of fit (i.e., PO, PG, PJ, person-person, and PV) are separated out and operate separately and differently at different times during the employment cycle. Edwards and Billsberry (2010) tested this idea and discovered that the conjecture that the various forms of fit operate separately holds. Since 2017, most studies have treated PO and PJ fit as separate, but associated, constructs that operate independently to influence outcomes (e.g., Abdalla et al. 2018; Huang 2021; Lim et al. 2019). In addition, NS and DA fit are increasingly being conceptualized as forms of PJ fit rather than PO fit (e.g., Hennekam et al. 2020; Rodrigues et al. 2020; Verelst et al. 2021), although Cao and Hamori (2020) and Guan et al. (2021) associate NS fit with reward management. Kim et al. (2020) conceptualized PJ, NS, and DA fit separately, thereby demonstrating the ongoing challenge to define PO fit and its associated constructs.

Job crafting is an emerging theme in studies at the interface of PO and PJ fit. Job crafting refers to employees’ self-initiated efforts to shape, mould, and redefine their jobs to make them align better with their values, interests, motives, and passions (Kooij et al. 2017; Tims et al. 2012; Vogel et al. 2016; Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001). In a study that looked at how professional ballet dancers assess and adjust their DA and NS fit across their work lifespan, Rodrigues et al. (2020) showed that workers crafted their jobs throughout the phases of their lifetime with perhaps more emphasis on job crafting later in careers and this job crafting leads to higher levels of PJ fit and better psychological well-being. This study raises interesting questions about the interface of job, role, and career crafting, the type of levers that workers can pull to craft their jobs, and the impact of crafting on PO and PJ fit. The study also shows that employees employ different crafting strategies at different stages of their lifespan with midlife workers preserving resources and older workers “compensating for their losses in personal resources by finding a new goal” (Rodrigues et al. 2020:12) in an effort to maintain their DA fit. These findings open a further window in PO fit research about the interaction of age and career stage on the construct, which are topics rarely touched upon in previous PO fit research.

7.4 Contemporary theme 3: ethical considerations

Many scholars have sought to determine how ethics, broadly defined as actions to improve the well-being of the environment, societies, and the individuals in them, relates to PO fit or the fit between an individual and their future profession. Until recently, the emphasis of ethical investigation has been on how ethical considerations influence employees’ decisions to join, find satisfaction, and stay in their jobs (e.g., Coldwell et al. 2008). In studies published in 2018 or later, the focus has changed: the focus is on the extent to which employees can be influenced to act more ethically by improving their PO fit. This is prompted by resource-based and dynamic capability views of the firm, which suggest that having employees act ethically is a potential source of business value. Studies have shown that higher levels of PO fit can be achieved by strengthening the organization’s ethical climate (Al Halbusi et al. 2020), improving managers’ ethical leadership (Al Halbusi et al. 2020a, b; Dimitriou and Schwepker 2019), matching employees’ and the organization’s levels of spirituality (Koburtay and Haloub 2022), making the organization’s HRM more socially responsible (Zhao et al. 2021), and improving organizational justice (Al Halbusi et al. 2020a, b).

But findings are mixed. Improving PO fit sometimes improves employees’ ethical behaviour as they perform their job tasks or causes them to engage in other ethically desirable behaviours such as personal growth initiatives or corporate social responsibility initiatives (Kang et al. 2018; Nejati et al. 2019). However, the positive effect on employee ethical behaviour is much stronger if employees already place high personal value on the specific factor(s) the organization changed in order to improve PO fit. Moreover, the association between better PO fit and more ethical behaviour was not always clear-cut. Schwepker (2019) found that trust in the manager was necessary in addition to better PO fit if salespeople were to deliver better customer value. Similarly, Kerse (2021) found that organizational trust was also needed if employees were to engage in extra-role behaviours.

8 Discussion and future research directions

8.1 Discussion

Bibliometric analysis offers a different way of systematically reviewing a literature compared to narrative and meta-analysis. Where the latter two tend to have an integrative nature, bibliometric analysis reveals milestones, trends, and trajectories. The goal is not to develop new theory, but to surface what topics are being currently studied and where they have emerged from. In effect, it offers a primer for anyone interested in conducting research in the target subject. As noted earlier, this bibliometric analysis of the PO fit literature discovered that the number of journal articles published each year is increasing rapidly and the field has matured into a subject worthy of attention in its own right. In addition, it is a dynamic field that is moving away from its early roots. Studies conducted during the formative years of PO fit research tended to focus on the nomological network of the construct and studies during the organizational entry phase of employment. These are very different to the primary areas for contemporary study in PO fit, which focus on employee engagement, employees’ interactions with their jobs, and ethical considerations.

In many senses, bibliometric analysis is a precursor to more detailed analytical reviews such as those done through meta-analysis, systematic review, or narrative review. It performs a cartographic analysis of a field of study prompting more targeted analysis. The questions this study could not answer, but which have been points of contention in this field include the conceptualization of PO fit and its measurement and calculation. This study showed that PO fit research has shifted away from organizational entry and moved more towards people in employment. During organizational entry, PO fit is commonly conceptualized as anticipatory PO fit (Evertz and Süß 2017; e.g., how I think I will fit this new organization, or, how I think the new recruit will fit in), whereas when looking at people in employment, PO fit is more likely to be conceptualized in the ‘here and now’ (e.g., how well do I fit? or, how strong is the PO fit of these employees?). This suggests that not only has the focus of PO fit researchers shifted, but so might the way they conceptualize PO fit. Further, with anticipatory fit, participants are commonly given indirect measures of PO fit that compare one aspect of them, typically their values (e.g., Billsberry 2007; Cable and Judge 1996, 1997; Chatman 1991), with some other feature. This captures an indication of actual fit that aids the personnel selection assessment. Direct measures (e.g., Cable and DeRue 2002) are occasionally used to capture perceived anticipatory fit, but these are likely to be much more commonly used to capture someone’s perceived sense of their current PO fit. So, with the shift in focus demonstrated in this bibliometric review, there are likely to be changes in how PO fit researchers in contemporary studies are measuring the construct. Systematic reviews would be ideal mechanisms to explore these issues in more depth and to see whether PO fit researchers have changed the ways they conceptualize and measure the construct.

Definitions are an enduring problem in the field of PO fit with researchers typically saying that PO fit is an elusive construct or one that defies definition (e.g., Harrison 2007; Kristof-Brown and Billsberry 2013; Rynes and Gerhart 1990; Wheeler et al. 2005). As noted earlier in this paper, PO fit has been conceptualized, measured, and calculated in many different ways. At times, it seems that there are as many definitions as there are scholars working in the field. With the proliferation of PO fit studies in recent years, whilst a few more definitions and approaches have emerged, there has also been increasing agreement on the types of PO fit studied and how they should be measured. In atomistic forms of PO fit, it is now commonplace to see scholars using polynomial regression and response surface graphs to analyse the interaction of personal and organizational variables. In these studies, PO fit is less about understanding the psychological construct of PO fit and more about a suite of tools and techniques to compare the interaction of two independent variables on a single dependent variable. With perceived PO fit, Cable and DeRue’s (2002) scale and similar ones are now employed in a large number of empirical studies which conceptualize PO fit as PO value congruence. Reviewing these empirical papers, it is clear that researchers’ interest is including PO fit (or PO misfit) in their studies and they are choosing to use the most commonly used instruments and techniques to capture it. Rarely is there any discussion about the nature of PO fit and the associated choice of tool (cf. Chi et al. 2020; Doblhofer et al. 2019). As a result, the increasing consensus on studying PO fit through polynomial regression, response surface graphs, and perceived PO value congruence is a result of methodological necessity or convenience rather than indicating a consensus about how PO fit should be defined and conceptualized. It does not necessarily confer consensus about the nature, definition, or conceptualization of PO fit.

To illustrate this point, qualitative studies of fit are demonstrating that it is much more multi-faceted than an interaction or alignment of person and organization variables. For example, Jansen and Shipp (2019) followed the fit stories of 32 mid-career, long-tenured professionals identifying four prototypical fit trajectories. They focused on the periods in people’s fit trajectories when they regarded themselves as misfits as a way to expose what really matters to their fit. Echoing the findings of Follmer et al. (2018), they discovered that fit can be associated with single events or a slow unfolding over time, and it can relate to supervisors, career progression, leadership change, jobs, teams, colleagues, vocation, values, identity, and personal ambition and drive. Teasing out the PO components from other aspects of fit is troublesome because these various forms of fit are interacting amongst themselves. The sense coming from such studies is that PO fit (and other forms of fit and misfit) is inherently multi-faceted, and it includes different currencies, conceptualizations, and constructions. Hence, the increasing homogenization of PO fit research methods around polynomial regression, response surface graphs, and value congruence is masking an underlying definitional challenge that has not gone away. This elusiveness is perhaps the most pressing concern for future PO fit research. There is still a need to discover exactly what PO fit is.

Since its inception, there has been a tension at the heart of PO fit research as it has simultaneously ‘spoken’ to individual and organizational outcomes. For example, Chatman’s (1989) theoretical work on PO fit highlighted the impact of PO fit on individual outcomes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and tenure, whilst Schneider’s (1987) work centred on organizational outcomes such as organizational culture, levels of creativity, and organizational health. The great challenge in conducting empirical work to test Schneider’s (and others’) organizational propositions is isolating and measuring the impact of individual-level psychological effects on organizational-level outcomes when so many other factors are involved. Not surprisingly, therefore, almost all studies captured in this bibliometric review focused on individual-level forms of analysis. Typically, individuals’ psychological fit is used as an independent variable (e.g., perceived fit, NS fit, and DA fit) predicting individual-level dependent variables (e.g., employee engagement, job satisfaction, and intent to leave). Consequently, we have a lot of data about the detailed effect of PO fit on individuals, but very little information about the impact of this PO fit on the organization. We still do not know, for example, whether high levels of PO fit are good for the organization or not. Higher levels of job satisfaction, employee engagement, and organizational commitment would appear to be good things, but Schneider (1987:446) warns that high levels of homogeneity in organizations leads to the equivalent of organizational “dry rot”. Others (e.g., Amis et al. 2020; Arthur Jr et al. 2006; Björklund et al. 2012; Harrison 2007; Powell 1998) are concerned that high levels of PO fit perpetuate privilege, bias, and unfairness in organizations. This unresolved tension in the literature can only be addressed with empirical studies including organizational-level dependent variables, which means that a pressing concern in the PO fit literature is working out how to isolate and measure the influence of individual factors (i.e., PO fit) on organizational outcomes.

One omission from the study surprised us greatly. De Cooman et al. (2019) report that a similar publication trend can be found in misfit research with the number of publications on the topic rising steeply in recent years. This subject is relevant to the PO fit literature because misfit has been a key element of PO fit theorizing. In the early days of PO fit, when the focus of the literature was skewed towards recruitment, selection, and socialization settings, misfit was an important consideration because recruiting people low in fit (‘misfits’) was thought to be unfavourable to them as well as the organization (Chatman 1989) causing them to leave and creating organizational homogeneity (Schneider 1987; Schneider et al. 1998). Moreover, advances in calculating PO fit in quantitative studies have focused on polynomial regression and surface response graphs (Edwards 2001; Edwards and Cable 2009) where establishing the interaction lines of fit and misfit are central to interpreting results. Further, one of the primary instruments used to study perceived employee misfit, Cable and DeRue (2002), is a measure of PO fit where low scores have been used to explore the construct. So, misfit might be expected to appear strongly in this literature. Therefore, it was quite a surprise that ‘misfit’ did not feature in the lists of keywords either in the whole literature or in more recent times. Over the whole span of the study, ‘misfit’ only appeared six times: Brigham et al. (2010), Brown et al. (2020), Kim et al. (2021), Pečarič (2018), Pérez-Nordtvedt et al. (2008), and Zubielevitch et al. (2021). This absence speaks volumes about the PO fit literature. It shows that PO fit research has focused on the positive aspects of fit rather than the negative experience of misfit. PO fit is primarily concerned with the vast majority of workers who ‘broadly’ fit at work and their associated job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and engagement (not their job dissatisfaction, lack of commitment, or disengagement). Of course, depending on how it is measured, PO fit is typically the study of misfit: few people are ‘perfect fits’ and all have some element of misfit. But the mainstream PO fit literature approaches the topic from a developmental point of view where lower levels of fit are addressable and not pathological (e.g., Vogel et al. 2016). Moreover, the small number of co-occurrences of PO fit (and related terms) and misfit in the keywords suggests that PO fit and misfit might be establishing themselves in their own right as separate research domains.

This absence opens the door to future research. As mentioned, misfit has been clearly noted as a key element of PO fit influencing employees’ satisfaction, commitment, retention, and mental well-being (Chatman 1989; Hylén et al. 2018; Lamiani et al. 2018) and also the health of organizations (Schneider 1987). As such, the absence of coverage of these factors in the PO fit literature offers an opportunity to study these potentially important negative impacts for employees and organizations. Are high and low levels of fit (and misfit) influenced by the same factors? Are they two sides of the same coin, or different coins? Can fit and misfit co-exist? For example, could someone fit their job but misfit their organization? What are the implications of such contradictions or paradoxes? Does it result in cognitive dissonance or can employees compartmentalize such contrasting fit reactions?

8.2 2022 Update

The data gathering for this paper occurred on 9 June 2021. Approximately a year later, the paper completed its journey through the review process giving us the opportunity to observe whether the trends we reported in the paper had continued. On 14 July 2022, we re-ran the search on the same database. Due to ‘in press’ and ‘online first’ papers appearing in print and their details updating, the number of papers published in recent years can be revised. 2018 decreases from 71 to 58. 2019 decreases from 86 to 61. 2020 decreases from 117 to 86. In addition, full year figures for 2021 can be supplied. 110 papers were published on PO fit in 2021. These figures support the trend identified in this paper that the number of journal articles published on PO fit continues to rise each year.

Adding the additional year of data yields a similar network of contemporary keywords. However, there was a significant difference in the analysis of authors’ country affiliation with China moving above the United Kingdom into second place. Further analysis of the contribution of scholars at Chinese institutions in 2021 and 2022 shows that the proportion of papers crediting Chinese universities is at 16% for this year and a half (up from 8%, 1982–2021) and US universities is at 25% (down from 41%, 1982–2021) suggesting a significant shift of axis in the scholarship of PO fit research. One journal, Frontiers in Psychology, has moved up in the ranking of journals publishing PO fit research. On 14 July 2022, it had published 18 journal papers on PO fit, up from 12, placing it 5th all-time as an outlet for PO fit research.

8.3 Limitations

Several factors limit the ability to generalize from this study. First, it was conducted on the Scopus database. The benefits of doing this, as discussed in the method section, include excellent breadth and quality considerations. However, some journals are not listed in the Scopus database and some journal papers are not listed even when the journal is covered. To reduce the impact of this limitation, we conducted completeness checks through Google Scholar, and surfaced three papers from the early years of digital libraries (Chatman 1989, 1991; O’Reilly et al. 1991) to add to the list of seminal articles. However, to aid the replicability of the study, we otherwise excluded them from the analysis.

A second limitation relates to the specific conditions of the search. Our goals were to get an overview of research published on PO fit in refereed journals. To do this, our search terms were ‘person-organization’ (and the English alternative spelling) and ‘fit’ in the titles, abstracts, or keywords of papers. The Scopus search engine proved to be very accurate and only returned a few conference papers, book chapters, non-English papers, and off-topic papers that were easily removed. However, the specificity of the search means that papers on PO fit that do not include the words ‘person-organization’ and ‘fit’ in titles, abstracts, or keywords were not discovered. Papers not mentioning these words are unlikely to have PO fit as a major component of their studies, but there will be some omissions. Also, studies that focus on misfit, or value congruence, or value incongruence, which are very closely related to PO fit (e.g., Cooper-Thomas and Wright 2013; Follmer et al. 2018; Vogel et al. 2016) will not surface if they do not mention PO fit in these fields. This will also hide a few articles (e.g., Rynes and Gerhart 1990) that were published before the phrase ‘person-organization fit’ became the standard nomenclature for PO fit studies, and some on Schneider’s (1987) Attraction-Selection-Attrition framework. We made this decision for precision in discovering extant knowledge on PO fit, but scholars interested in such related subjects may want to extend our research.

9 Conclusions

PO fit has long been regarded as an elusive construct under which many forms of fit, congruence, alignment, and compatibility shelter (Harrison 2007; Kristof 1996; Kristof and Billsberry 2013; Rynes and Gerhart 1990). This bibliographic analysis has brought some clarity to the field and demonstrated that PO fit now stands as a separate and independent field of study. In addition, this study has shown that the PO fit literature has moved on from studies looking at the initial and terminal phases of employment and now focuses more on employees. Similarly, the field has transitioned from studying the association of PO fit with job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and other affective outcomes and now focuses more on issues around engagement and equity.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

The syntax used to gather data is replicated in the Appendix.

References

Abdalla A, Elsetouhi A, Negm A, Abdou H (2018) Perceived person-organization fit and turnover intention in medical centers: The mediating roles of person-group fit and person-job fit perceptions. Pers Rev 47:863–881. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-03-2017-0085

Al Halbusi H, Williams KA, Mansoor HO, Hassan MS, Hamid FAH (2020a) Examining the impact of ethical leadership and organizational justice on employees’ ethical behavior: Does person–organization fit play a role? Ethics Behav 30:514–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2019.1694024

Al Halbusi H, Williams KA, Ramayah T, Aldieri L, Vinci CP (2020b) Linking ethical leadership and ethical climate to employees’ ethical behavior: The moderating role of person–organization fit. Pers Rev 50:159–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-09-2019-0522

Amis JM, Mair J, Munir KA (2020) The organizational reproduction of inequality. Acad Manag Ann 14:195–230. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2017.0033

Arthur W Jr, Bell S, Villado A, Doverspike D (2006) The use of person-organization fit in employment decision making: An assessment of its criterion-related validity. J Appl Psychol 91:786–801. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.786

Billsberry J (2007) Attracting for values: An empirical study of ASA’s attraction proposition. J Manag Psychol 22:132–149. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710726401

Björklund F, Bäckström M, Wolgast S (2012) Company norms affect which traits are preferred in job candidates and may cause employment discrimination. J Psychol 146:579–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2012.658459

Block JH, Fisch C (2020) Eight tips and questions for your bibliographic study in business and management research. Manag Rev Q 70(3):307–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-020-00188-4

Brigham KH, Mitchell RK, De Castro JO (2010) Cognitive misfit and firm growth in technology-oriented SMEs. Int J Technol Manag 52:4–25. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijtm.2010.035853

Brown LW, Manegold JG, Marquardt DJ (2020) The effects of CEO activism on employees’ person-organization ideological misfit: A conceptual model and research agenda. Bus Soc Rev 125:119–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12196

Bühren C, Meier F, Pleßner M (2022) Ambiguity aversion: Bibliometric analysis and literature review of the last 60 years. Manag Rev Q 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-021-00250-9

Cable DM, DeRue DS (2002) The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J Appl Psychol 87:875–884. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.5.875

Cable DM, Judge TA (1994) Pay preferences and job search decisions: A person-organization fit perspective. Pers Psychol 47:317–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1994.tb01727.x

Cable DM, Judge TA (1996) Person–organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 67:294–311. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1996.0081

Cable DM, Judge TA (1997) Interviewers’ perceptions of person-organization fit and organizational selection decisions. J Appl Psychol 82:546–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.546

Cartwright S, Schoenberg R (2006) Thirty years of mergers and acquisitions research: Recent advances and future opportunities. Brit J Manag 17(S1):S1–S5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.00475.x

Cao J, Hamori M (2020) How can employers benefit most from developmental job experiences? The needs-supplies fit perspective. J Appl Psychol 105:422–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000449

Chapman DS, Uggerslev KL, Carroll SA, Piasentin KA, Jones DA (2005) Applicant attraction to organizations and job choice: A meta-analytic review of the correlates of recruiting outcomes. J Appl Psychol 90:928–944. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.928

Chatman J (1989) Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Acad Manag Rev 14:333–349. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4279063

Chatman JA (1991) Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Adm Sci Q 36:459–484. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393204

Chawla P (2020) Impact of employer branding on employee engagement in business process outsourcing (BPO) sector in India: Mediating effect of person–organization fit. Ind Commer Train 15:35–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/ict-06-2019-0063

Chi N, Fang L, Shen C, Fan H (2020) Detrimental effects of newcomer person-job misfit on actual turnover and performance: The buffering role of multidimensional person-environment fit. Appl Psychol Int Rev 69:1361–1395. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12225

Coldwell DA, Billsberry J, Van Meurs N, Marsh PJG (2008) The effects of person-organization ethical fit on employee attraction and retention: Towards a testable explanatory model. J Bus Ethics 78:611–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9371-y

Cooper-Thomas HD, Wright S (2013) Person-environment misfit: The neglected role of social context. J Manag Psychol 28:21–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941311298841

Das R (2022) Does public service motivation predict performance in public sector organizations? A longitudinal science mapping study. Manag Rev Q 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11301-022-00273-w/figures/8

De Cooman R, Mol ST, Billsberry J, Boon C, Den Hartog DN (2019) Epilogue: Frontiers in person–environment fit research. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 28:646–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1630480

Deng H, Wu C-H, Leung K, Guan Y (2015) Depletion from self-regulation: A resource-based account of the effect of value incongruence. Pers Psychol 69:431–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12107

Dimitriou CK, Schwepker CH (2019) Enhancing the lodging experience through ethical leadership. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 31:669–690. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijchm-10-2017-0636

Doblhofer DS, Hauser A, Kuonath A, Haas K, Agthe M, Frey D (2019) Make the best out of the bad: Coping with value incongruence through displaying facades of conformity, positive reframing, and self-disclosure. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 28:572–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2019.1567579

Edwards JA, Billsberry J (2010) Testing a multidimensional theory of person-environment fit. J Manag Issues 22:476–493

Edwards JR (2001) Ten difference score myths. Organ Res Methods 4:265–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810143005

Edwards JR (2008) Person-environment fit in organizations: An assessment of theoretical progress. Acad Manag Ann 2:167–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520802211503

Edwards JR, Cable DM (2009) The value of value congruence. J Appl Psychol 94:654–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014891

Edwards JR, Cable DM, Williamson IO, Lambert LS, Shipp AJ (2006) The phenomenology of fit: Linking the person and environment to the subjective experience of person-environment fit. J Appl Psychol 91:802–827. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.802

Evertz L, Süß S (2017) The importance of individual differences for applicant attraction: A literature review and avenues for future research. Manag Rev Q 67:141–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-017-0126-2

Follmer EH, Talbot DL, Kristof-Brown AL, Astrove SL, Billsberry J (2018) Resolution, relief, and resignation: A qualitative study of responses to misfit at work. Acad Manag J 61:440–465. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0566

Guan Y, Deng H, Fan L, Zhou X (2021) Theorizing person-environment fit in a changing career world: Interdisciplinary integration and future directions. J Vocat Behav 126:103557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103557

Harrison DA (2007) Pitching fits in applied psychological research: Making fit methods fit theory. In: Ostroff C, Judge T (eds) Perspectives on organizational fit. Lawrence Erlbaum, New York, pp 389–416

Hennekam S, Follmer K, Beatty JE (2020) The paradox of mental illness and employment: A person-job fit lens. Int J Hum Resour Manag. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1867618

Hicklenton C, Hine DW, Loi NM (2019) Does green-person-organization fit predict intrinsic need satisfaction and workplace engagement? Front Psychol 10:2285. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02285

Hoffman B, Woehr D (2006) A quantitative review of the relationship between person–organization fit and behavioral outcomes. J Vocat Behav 68(3):389–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.08.003

Huang J-C (2021) Effects of person-organization fit objective feedback and subjective perception on organizational attractiveness in online recruitment. Pers Rev. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-06-2020-0449

Hylén U, Kjellin L, Pelto-Piri V, Warg LE (2018) Psychosocial work environment within psychiatric inpatient care in Sweden: Violence, stress, and value incongruence among nursing staff. Int J Ment Health Nurs 27:1086–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12421

Iqbal M, Adawiyah WR, Suroso A, Wihuda F (2020) Exploring the impact of workplace spirituality on nurse work engagement: An empirical study on Indonesian government hospitals. Int J Ethics Syst 36:351–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijoes-03-2019-0061

Jansen KJ, Kristof-Brown A (2006) Toward a multidimensional theory of person-environment fit. J Manag Issues 18:193–212

Jansen KJ, Shipp AJ (2019) Fitting as a temporal sensemaking process: Shifting trajectories and stable themes. Hum Rel 72:1154–1186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718794268

Kang S, Han SJ, Bang J (2018) The fit between employees’ perception and the organization’s behavior in terms of corporate social responsibility. Sustain 10:1650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051650

Kao K-Y, Hsu H-H, Thomas CL, Cheng Y-C, Lin M-T, Li H-F (2021) Motivating employees to speak up: Linking job autonomy, P-O fit, and employee voice behaviors through work engagement. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01222-0

Kerse G (2021) A leader indeed is a leader in deed: The relationship of ethical leadership, person-organization fit, organizational trust, and extra-role service behavior. J Manag Organ 27:601–620. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2019.4

Kim SH, Wagstaff MF, Laffranchini G (2021) Does humane orientation matter? A cross-cultural study of job characteristics needs-supplies fit/misfit and affective organizational commitment. Cross Cult Strat Manag 28:600–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/ccsm-08-2020-0171

Kim TY, Schuh SC, Cai Y (2020) Person or job? Change in person-job fit and its impact on employee work attitudes over time. J Manag Stud 57:287–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12433

Koburtay T, Haloub R (2022) Does person–organization spirituality fit stimulate ethical and spiritual leaders: A empirical study in Jordan. Pers Rev 51:317–334. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-06-2020-0492

Kooij DTAM, van Woerkom M, Wilkenloh J, Dorenbosch L, Denissen JJA (2017) Job crafting towards strengths and interests: The effects of a job crafting intervention on person–job fit and the role of age. J Appl Psychol 102:971–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000194

Kristof AL (1996) Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers Psychol 49:1–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb01790.x

Kristof-Brown AL, Billsberry J (2013) Fit for the future. In: Kristof-Brown AL, Billsberry J (eds) Organizational fit: Key issues and new directions. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, pp 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118320853.ch1

Kristof-Brown AL, Guay RP (2011) Person-environment fit. In: Zedeck S (ed) APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, vol 3. American Psychological Association, Washington DC, pp 3–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/12171-001

Kristof-Brown AL, Zimmerman RD, Johnson EC (2005) Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Pers Psychol 58:281–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

Lamiani G, Dordoni P, Argentero P (2018) Value congruence and depressive symptoms among critical care clinicians: the mediating role of moral distress. Stress Health 34:135–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2769

Lim S, Lee KH, Bae KH (2019) Distinguishing motivational traits between person-organization fit and person-job fit: Testing the moderating effects of extrinsic rewards in enhancing public employee job satisfaction. Int J Pub Adm 42:1040–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1575665

Linnenluecke MK, Marrone M, Singh AK (2019) Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Aust J Manag 45:175–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219877678

Lv Z, Xu T (2018) Psychological contract breach, high-performance work system and engagement: The mediated effect of person-organization fit. Int J Hum Resour Manag 29:1257–1284. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1194873

Martín-Martín A, Thelwall M, Orduna-Malea E, López-Cózar ED (2021) Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic, Scopus, Dimensions, Web of Science, and OpenCitations’ COCI: A multidisciplinary comparison of coverage via citations. Scientometr 126:871–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03690-4

Matteson MT, Ivancevich JM (1982) Type A and B behavior patterns and self-reported health symptoms and stress: Examining individual and organizational fit. J Occup Med 24:585–589. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-198208000-00012

Memon MA, Salleh R, Nordin SM, Cheah J-H, Ting H, Chuah F (2018) Person-organisation fit and turnover intention: The mediating role of work engagement. J Manag Dev 37:285–298. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmd-07-2017-0232

Mingers J, Lipitakis EAECG (2010) Counting the citations: a comparison of Web of Science and Google Scholar in the field of business and management. Scientometr 85:613–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0270-0

Morrow R, Brough P (2019) ‘It’s off to work we go!’ Person–environment fit and turnover intentions in managerial and administrative mining personnel. Int J Occup Saf Ergon 25:467–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2017.1396028

Mostafa AMS, Andrews R (2018) Senior public managers’ engagement: A person–situation–interactionist perspective. Int J Pub Adm 41:1279–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2017.1387141

Nejati M, Salamzadeh Y, Loke CK (2019) Can ethical leaders drive employees’ CSR engagement? Soc Responsib J 16:655–669. https://doi.org/10.1108/srj-11-2018-0298

Nakagawa S, Samarasinghe G, Haddaway NR, Westgate MJ, O’Dea RE, Noble DWA, Lagisz M (2018) Research weaving: Visualizing the future of research synthesis. Trends Ecol Evol 34:224–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2018.11.007

O’Reilly CA, Chatman J, Caldwell DF (1991) People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Acad Manag J 34:487–516. https://doi.org/10.2307/256404

O’Reilly CA, Williams KY, Barsade S, Composition (1998)Elsevier Science/JAI Press, London,pp 183–207

Pečarič M (2018) A transparent legal system of indicators as the indicator of personal fit. Int J Organ Anal 26:171–184. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijoa-08-2017-1210

Pérez-Nordtvedt L, Payne GT, Short JC, Kedia BL (2008) An entrainment-based model of temporal organizational fit, misfit, and performance. Organ Sci 19:785–801. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0330

Powell G (1998) Reinforcing and extending today’s organizations: The simultaneous pursuit of person-organization fit and diversity. Organ Dyn 26:50–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-2616(98)90014-6

Priyadarshi P, Premchandran R (2018) Job characteristics, job resources and work-related outcomes: Role of person-organisation fit. Evid-based HRM 6:118–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/ebhrm-04-2017-0022

Rai A, Nandy B (2021) Employer brand to leverage employees’ intention to stay through sequential mediation model: Evidence from Indian power sector. Int J Energy Sect Manag 15:551–565. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijesm-10-2019-0024

Rawshdeh ZA, Makhbul ZKM, Alam SS (2019) The mediating role of person-organization fit in the relationship between socially responsible-HRM practices and employee engagement. Hum Soc Sci Rev 7:434–441. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2019.7548

Rodrigues FR, Pina e Cunha M, Castanheira F, Bal PM, Jansen PGW (2020) Person-job fit across the work lifespan: The case of classical ballet dancers. J Vocat Behav 118:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103400

Rynes S, Gerhart B (1990) Interviewer assessments of applicant “fit”: An exploratory investigation. Pers Psychol 43:13–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1990.tb02004.x

Schwepker CH (2019) Strengthening customer value development and ethical intent in the salesforce: The influence of ethical values person–organization fit and trust in manager. J Bus Ethics 159:913–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3851-0

Schneider B (1987) The people make the place. Pers Psychol 40:437–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1987.tb00609.x

Schneider B, Goldstein HW, Smith DB (1995) The ASA framework: An update. Pers Psychol 48:747–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01780.x

Schneider B, Smith DB, Taylor S, Fleenor J (1998) Personality and organizations: A test of the homogeneity of personality hypothesis. J Appl Psychol 83:462–470. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.462

Sekhar C, Patwardhan M, Vyas V (2018) Linking work engagement to job performance through flexible human resource management. Adv Dev Hum Resour 20:72–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422317743250

Simao LB, Carvalho LC, Madeira MJ (2021) Intellectual structure of management innovation: Bibliometric analysis. Manag Rev Q 71:651–677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-020-00196-4

Straatmann T, Königschulte S, Hattrup K, Hamborg K-C (2020) Analysing mediating effects underlying the relationships between P–O fit, P–J fit, and organisational commitment. Int J Hum Resour Manag 31:1533–1559. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1416652

Thorndike EL (1950) The organization of a person. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 45:137–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0059075

Tims M, Bakker AB, Derks D (2012) Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J Vocat Behav 80:173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

Tom VR (1971) The role of personality and organizational images in the recruiting process. Organ Behav Hum Perf 6:573–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0030-5073(71)80008-9

van Eck NJ, Waltman L (2010) Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometr 84:523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

van Oorschot JAWH, Hofman E, Halman JIM (2018) A bibliometric review of the innovation adoption literature. Technol Forecast Soc Change 134:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.04.032

Verelst L, De Cooman R, Verbruggen M, van Laar C, Meeussen L (2021) The development and validation of an electronic job crafting intervention: Testing the links with job crafting and person-job fit. J Occup Organ Psychol 94:338–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12351

Verquer ML, Beehr TA, Wagner SH (2003) A meta-analysis of relations between person–organization fit and work attitudes. J Vocat Behav 63:473–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00036-2

Vogel RM, Rodell JB, Lynch JW (2016) Engaged and productive misfits: How job crafting and leisure activity mitigate the negative effects of value incongruence. Acad Manag J 59:1561–1584. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0850

Weber Y (2015) Development and training at mergers and acquisitions. Proced Soc Behav Sci 209:254–260. https://doi.org.10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.229

Wheeler AR, Buckley MR, Halbesleben JRB, Brouer RL, Ferris GR (2005) “The elusive criterion of fit” revisited: Toward an integrative theory of multidimensional fit. Res Pers Hum Resour Manag 24:265–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(05)24007-0

Wrzesniewski A, Dutton JE (2001) Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad Manag Rev 26:179–201. https://doi.org/10.2307/259118

Xie L, Chen Z, Wang H, Zheng C, Jiang J (2020) Bibliometric and visualized analysis of scientific publications on atlantoaxial spine surgery based on Web of Science and VOSviewer. World Neurosurg 137:435–442e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.01.171

Zhao H, Zhou Q, He P, Jiang C (2021) How and when does socially responsible HRM affect employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment? J Bus Ethics 169:371–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04285-7

Zubielevitch E, Cooper-Thomas HD, Cheung GW (2021) The (socio) politics of misfit: a moderated-mediation model misfit. J Manag Psychol 6:138–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmp-05-2020-0256

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor, Professor Joern Block, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Funding

There is no funding to report related to this paper.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent to participate

The authors consent to participate.

Consent for publication

The authors consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

The syntax used in the Scopus search was:

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( {needs-supplies} OR {demand-abilities} OR {NS fit} OR {DA fit} OR {N-S fit} OR {D-A fit} OR {person-organization fit} OR {person-organisation fit} OR {PO fit} OR {P-O fit} OR {(PO) fit} OR {employee-organization fit} OR {employee-organisation fit} OR {EO fit} OR {E-O fit} OR {(EO) fit} OR {organizational fit} OR {organisational fit} OR {needs—supplies} OR {demand—abilities} OR {N—S fit} OR {D—A fit} OR {person—organization fit} OR {person—organisation fit} OR {P—O fit} OR {employee—organization fit} OR {employee—organisation fit} OR {E—O fit} OR {needs–supplies} OR {demand–abilities} OR {N–S fit} OR {D–A fit} OR {person–organization fit} OR {person–organisation fit} OR {P–O fit} OR {employee–organization fit} OR {employee–organisation fit} OR {E–O fit} OR {needs supplies fit} OR {demand abilities fit} OR {N S fit} OR {D A fit} OR {person organization fit} OR {person organisation fit} OR {P O fit} OR {employee organization fit} OR {employee organisation fit} OR {E O fit} )

This inclusive syntax allowed for different spellings of the word ‘organization’, different ways of connecting the words ‘person’ and ‘organization’, different abbreviations, and alternative conceptualizations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Subramanian, S., Billsberry, J. & Barrett, M. A bibliometric analysis of person-organization fit research: significant features and contemporary trends. Manag Rev Q 73, 1971–1999 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00290-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00290-9