Abstract

It has frequently been noted in the wage bargaining literature that increasing average labour taxes may in fact be over-shifted in the pre-tax wage that is negotiated between unions and firms, raising workers post-tax wages. In this paper, we study the precise conditions for such tax over-shifting to occur under both Nash and Right-To-Manage bargaining structures, and considering both competitive and imperfectly competitive output market conditions. In the case of competitive output markets, we derive and interpret the conditions for over-shifting to occur and show that they hold for an entire class of commonly used production functions. Moreover, under monopolistically competitive output markets we show that tax over-shifting will occur when the firm has sufficient market power. The conditions on the production function, that were necessary and sufficient for tax over-shifting to occur under perfect competition, are shown to be no longer necessary. These findings hold for all bargaining structures considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although there are many papers analyzing the impact of the tax structure on employment and wages (Pissarides 1998 being one of the best examples), direct tests of tax over-shifting are very scarce because few studies explicitly consider increases in average tax rates holding marginal rates constant. Moreover, the available empirical analyses often consider revenue-neutral changes in tax structure, in which other policy instruments (e.g., unemployment benefits, etc.) are adjusted accordingly. As a consequence, the empirical results cannot be directly interpreted in terms of tax over-shifting alone.

The possibility of tax over-shifting on output prices has frequently been noted on imperfectly competitive markets (see, e.g., Hamilton 1999; Lockwood 1990; Stern 1987). More recently, Anderson et al. (2001) derive the specific conditions for tax over-shifting to occur for both ad valorem and unit taxes within the framework of a differentiated oligopoly.

Several papers (e.g., Koskela and Schöb 1999; Lockwood and Manning 1993) explicitly distinguish between wage and payroll taxes in a right-to-manage bargaining model. These are found to have slightly different implications, both theoretically and empirically. To keep the results on over-shifting as transparent as possible, note that we only consider wage taxes upon the employee.

As noted in the introduction, several authors have also considered increases in marginal tax rates at constant average rates. It is generally found that there is no over-shifting in this case, i.e., it reduces the post-tax wage (see, e.g., Malcomson and Sator 1987). This result is also easily reproduced for the model considered in this paper. Since this is not a novel finding, it is not included.

Note that, in principle, we can analyze such changes in taxes for a general tax function T(w, z). Some simple functional forms for the tax function do imply that the conditions T z > 0, T wz = 0 always hold; an example is a linear income tax schedule where we keep the marginal tax rate fixed while raising the intercept (Malcomson and Sator 1987; Pissarides 1998).

Given the specific focus of this paper on tax over-shifting, this assumption is convenient to obtain tractable results. It implies that we do not endogenize social security payments, such as unemployment benefits. Relaxing this assumption requires an optimal taxation approach that clearly specifies why taxes are being raised and that explicitly incorporates distributional issues.

This assumption makes the results that follow more transparent; qualitatively, it does not affect the message from this paper.

As an example, let \( f{\left( L \right)} = kL^{\alpha } ,\quad \alpha < 1 \). Then simple algebra shows \( fL + \frac{f} {L} - f\prime = {\left( {\alpha - 1} \right)}^{2} kL^{{\alpha - 1}} > 0 \) It follows that there is always over-shifting under Nash bargaining, given iso-elastic production technology.

The concavity of the right-to-manage bargaining objective function imposes a restriction on the convexity of the labor demand curve. However, one easily shows that there is a range of values for f such that concavity of the objective function holds and tax over-shifting does occur.

Consider again the iso-elastic example given before: \( f{\left( L \right)} = kL^{\alpha } ,\quad \alpha < 1 \). We have \( Lf\prime + f = \alpha {\left( {\alpha - 1} \right)}^{2} kL^{{\alpha - 2}} > 0 \). It follows that there is always over-shifting.

Demand for sector i’s product is typically written as: \( x_{i} = {\left( {\frac{{p_{i} }} {P}} \right)}^{\beta } \frac{E} {{nP}} \)where p i is the price in sector i, E is total consumer expenditures, n is the number of sectors and P is an aggregate price index. In this setup, the price elasticity is equal to minus the elasticity of substitution between different varieties in the consumer’s utility function. The firm is assumed to be interested in real profit, i /P. Similarly, union utility in an arbitrary sector is defined on real net wages: \( {\widetilde{W}_{i} = {\left[ {w_{i} - T{\left( {w_{i} ,z} \right)}} \right]}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\widetilde{W}_{i} = {\left[ {w_{i} - T{\left( {w_{i} ,z} \right)}} \right]}} P}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} P \). The model presented in this section is consistent with this setting, assuming that all sectors are identical in all other respects and that the aggregate price level is exogenous in nominal wage negotiations (so that one can normalize P = 1).

Note that imperfect competition effects enter in a simple linear way in Eq. 20. Of course, this is only true given our assumption of constant elasticities of demand. However, since the key mechanism underlying Result 3 is that higher wages, and hence lower output, can be offset by higher prices, Result 4 is likely to hold for nonconstant elasticities, as long as demand is downward sloping.

References

Anderson, S. P., de Palma, A., & Kreider, B. (2001). Tax incidence in differentiated product oligopoly. Journal of Public Economics, 81, 173–192.

Bayundir-Uppman, T., & Raith, G. M. (2003). Should high-tax countries pursue revenue-neutral ecological tax reforms? European Economic Review, 47, 41–60.

Creedy, J., & McDonald, I. M. (1991). Models of trade union behaviour: A synthesis. The Economic Record, 346–359.

Dixit, A., & Stiglitz, J. (1977). Monopolistic competition and optimal product diversity. American Economic Review, 67, 297–308.

Hamilton, S. (1999). Tax incidence under oligopoly: A comparison of policy approaches. Journal of Public Economics, 71, 233–245.

Koskela, E., & Schöb, R. (1999). Does the composition of wage and payroll taxes matter under Nash bargaining. Economics Letters, 64, 343–349.

Layard, R., & Nickell, S. (1986). Unemployment in Britain. Economica, 53, S121–S169.

Lockwood, B. (1990). Tax incidence, market power and bargaining structure. Oxford Economic Papers, 42, 187–209.

Lockwood, B., & Manning, A. (1993). Wage setting and the tax system: Theory and evidence for the United Kingdom. Journal of Public Economics, 52, 1–29.

Malcomson, J., & Sator, N. (1987). Tax push inflation in a unionized labour market. European Economic Review, 31, 1581–1596.

McDonald, I. M., & Solow, R. M. (1981). Wage bargaining and employment. American Economic Review, 71(5), 896–908.

Pissarides, C. (1998). The impact of employment tax cuts on unemployment and wages: The role of unemployment benefits and tax structure. European Economic Review, 42, 155–183.

Schöb, R. (2005). The double dividend hypothesis of environmental taxes: A survey. In H. Folmer & T. Tietenberg (Eds.), The international yearbook of environmental and resource economics 2005–2006. Cheltenham: Edgar Elgar.

Stern, N. (1987). The effects of taxation, price control and government contracts in oligopoly and monopolistic competition. Journal of Public Economics, 32, 133–158.

Wu, Y., & Zhang, J. (2000). Endogenous markups and the effects of income taxation: Theory and evidence from OECD countries. Journal of Public Economics, 77, 383–406.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Ben Lockwood and Wilfried Pauwels for useful suggestions. An anonymous referee provided many additional remarks that substantially improved the final version.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The first version of this paper was written while Calthrop was at Jesus College, Oxford.

Appendices

Appendix A

We here derive the condition for tax over-shifting in the case of Nash bargaining over wages and employment with imperfectly competitive output markets. First, differentiating the system of first-order conditions (18a–18b) and solving by Cramer’s rule yields the effect of a tax increase on the pre-tax wage:

where \( {\rm H} = g_{{1w}} g_{{2L}} - g_{{2w}} g_{{1L}} \). The various terms are given by:

Using λ′ < 0, assuming positive profit, and noting that system (18a and 18b) implies:

the following signs can be shown to hold: g 1w > 0, g 1L < 0, g 2L > 0, g 1z < 0, H > 0. It then immediately follows that a tax increase raises negotiated wages:\( \frac{{dw}} {{dz}} > 0 \).

The effect of a tax increase on the net of tax wage is given by:

which leads after standard manipulations, using the above expressions, to:

Next, note that simple algebra allows us to write:

where

Substitution of Eq. A.2 in Eq. A.1 then yields:

so that \( {\left( {fL + \frac{f} {L} - f\prime } \right)} + K > 0 \) is a sufficient condition for tax over-shifting. This is expression (20) in the main body of the paper.

The term K captures the effects of imperfect competition. If we assumed perfect competition, K would be zero and we reproduce the results for perfect competition, see Eq. 10. Note that K can be shown to be positive as follows. First, use the Nash curve (18b) to obtain:

Substitute this into Eq. A.2, use the definition of profit \( \pi = pf - wL \), and rearrange to find:

This is positive as long as profit is positive.

Finally, interpretation of Eq. 20 is the same as under perfect competition. One easily shows that:

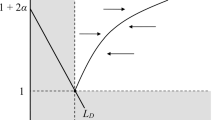

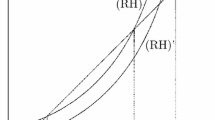

so that tax over-shifting occurs when the difference between average and marginal revenue product curves is declining in employment. Alternatively, the condition can again also be interpreted in terms of the difference in the slope of the Nash curve and the firm’s labour demand curve. Using Eq. 18b, the slope of the Nash curve is easily shown to be given by:

Similarly, the slope of the labour demand curve is easily derived as:

Comparison of the slopes immediately produces the desired result. Finally, the expression for the slope of the Nash curve also shows that tax over-shifting depends on the effect of higher union power on the wage sensitivity of labour demand.

For purposes of further interpretation, note that, at given employment, K can be written as a function of the price elasticity only, i.e., K(). Moreover, simple differentiation then shows that, provided that K() > 0, we have \( \frac{{\partial K{\left( \beta \right)}}} {{\partial \beta }} > 0 \). This observation is used in the main body of the paper.

Appendix B

For the right to manage model, the first order condition of the bargaining problem can be written as:

It immediately follows that an increase in the average tax rate raises the negotiated wage:

since \( g_{{3w}} = \mu {\left[ {\frac{{{\left( {1 - T_{w} } \right)}^{2} }} {{U - D}}{\left( {\lambda \prime - \frac{{\lambda ^{2} }} {{U - D}}} \right)} + \frac{1} {L}{\left( {\frac{{\partial ^{2} L^{{\text{d}}} {\left( w \right)}}} {{\partial ^{2} w}} - \frac{1} {L}{\left( {\frac{{\partial L^{{\text{d}}} {\left( w \right)}}} {{\partial w}}} \right)}^{2} } \right)}} \right]} - {\left( {1 - \mu } \right)}{\left[ {\frac{1} {\pi }\frac{{\partial L^{{\text{d}}} {\left( w \right)}}} {{\partial w}} + \frac{{L^{2} }} {{\pi ^{2} }}} \right]} \) is negative by the second order condition.

Furthermore, the impact on the net of tax wage is given by:

This can easily be shown to be:

An interesting issue is whether imperfect competition raises or reduces the likelihood of tax over-shifting under right to manage bargaining. By working out the various terms appearing in Eq. B.1, this question can be answered.

First, differentiating the slope of the labour demand curve derived before, see Eq. A.4, and rearranging we have:

Combining Eqs. A.4 and B.2, we further derive:

where

It follows from Eq. B.3 that a sufficient condition for tax over-shifting under the monopoly union model is given by \( Lf\prime + f + R > 0 \), see Eq. 23 in the main body of the paper.

To see the determinants of the sign of R, note that a sufficient condition for it to be positive is that

be negative. Now note from the condition for profit maximising behaviour

that

Substituting in Eq. B.5 implies using the definition of profit and some simple rearrangement:

Since the price elasticity was assumed to strictly exceed unity in absolute value and profit relative to revenues is smaller than one, it follows from Eqs. B.4 to B.6 that R will be positive unless the price elasticity is very large, i.e., unless the firm has very limited market power.

Note that at given employment, the term R can be written directly as a function of the price elasticity only: R = R(). As before, simple differentiation then shows that, provided R() > 0, we have \( \frac{{\partial R{\left( \beta \right)}}} {{\partial \beta }} > 0 \). This observation is used to arrive at Proposition 4 in the text.

Second, when the firm has some negotiation power, the term \( \pi \frac{{\partial L^{{\text{d}}} {\left( w \right)}}} {{\partial w}} + L^{2} \) also matters. Rewrite this term as:

Then substitute the profit maximising price into the definition of profit, use Eq. A.4, and rearrange to find:

where K is defined as in Eq. A.2:

For the right to manage model, using the first order condition for profit maximising behaviour, K can again be shown to be positive.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Calthrop, E., De Borger, B. On Tax Over-Shifting in Wage Bargaining Models. Atl Econ J 35, 127–143 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-007-9063-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-007-9063-0