Abstract

Amylase is one of the earliest characterized enzymes and has many applications in clinical and industrial settings. In biotechnological industries, the amylase activity is enhanced through modifying amylase structure and through cloning and expressing targeted amylases in different species. It is important to understand how engineered amylases can survive from generation to generation. This study used phylogenetic and statistical approaches to explore general patterns of amylases evolution, including 3118 α-amylases and 280 β-amylases from archaea, eukaryota and bacteria with fully documented taxonomic lineage. First, the phylogenetic tree was created to analyze the evolution of amylases with focus on individual amylases used in biofuel industry. Second, the average pairwise p-distance was computed for each kingdom, phylum, class, order, family and genus, and its diversity implies multi-time and multi-clan evolution. Finally, the variance was further partitioned into inter-clan variance and intra-clan variance for each taxonomic group, and they represent horizontal and vertical gene transfer. Theoretically, the results show a full picture on the evolution of amylases in manners of vertical and horizontal gene transfer, and multi-time and multi-clan evolution as well. Practically, this study provides the information on the surviving chance of desired amylase in a given taxonomic group, which may potentially enhance the successful rate of cloning and expression of amylase gene in different species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Amylase catalyzes the hydrolysis of 1,4-glycosidic linkages of starch to sugar. So far, several groups of amylases have been defined (Schomburg et al. 2013), and α- and β-amylases have many applications in clinical and biotechnological settings.

α-Amylase, EC 3.2.1.1, is generally considered to account for the majority of amylases in nature, and is the major component in various databases. There are 3398 amylases with fully documented taxonomic lineage in the release 2014_02 of UniProtKB (The UniProt Consortium 2010), and 3118 (91.76 %) are α-amylases. α-Amylase widely exists across taxonomic kingdoms, for these 3398 amylases, α-amylases account for 100, 98.47 and 66.99 % of amylases in archaea, bacteria and eukaryota, respectively. α-Amylase has wide applications in both clinical and industrial settings. In clinical settings, great interest is directed to hyperamylasemia that is associated with pancreatitis (Elsayed et al. 2014; Hernández Garcés et al. 2014) and biliopancreatic duct ligation (Fishman et al. 2014), and the α-amylase level in urine is also clinically meaningful (Voskuil et al. 2014). Still, α-amylase serves as a predictor of pancreatic fistula (Partelli et al. 2014), and a salivary biomarker for acute stress (Koh 2014), gastricaspiration (Sole et al. 2014), etc. On the one hand, α-amylase plays a role in degradation of dietary components by digestive tract microbiotic flora (Tzuc et al. 2014). On the other hand, inhibition of α-amylase is equally important for the control of post-prandial hyperglycemia (Wulan et al. 2014), so the inhibition of human salivary α-amylase could be potentially useful in the prevention and treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes as well (Bharathi et al. 2014; Gupta et al. 2014; Podsędek et al. 2014; Tiwari 2014). In addition, applications of α-amylase are widely used in fruit juice industry (Dey and Banerjee 2014), for example, bioconversion of wastes into hydrogen and methane (Kumar et al. 2014), bioethanol production (Pervez et al. 2014), textile industry (Deng et al. 2014), chicken feed enzyme (Jianhua et al. 2014), paper recycling (Raul et al. 2014), and detergent industry (Zaferanloo et al. 2014).

β-Amylase, EC 3.2.1.2, doubtlessly occupies the second position in various databases. Of 3398 amylases with fully documented taxonomic lineage in the release 2014_02 of UniProtKB, 280 (8.24 %) are β-amylases, which also widely exists across taxonomic kingdoms. For these 280 β-amylases, they account for 1.53 and 33.01 % of amylases in bacteria and eukaryota. β-Amylase works from the non-reducing end of starch and catalyzes the hydrolysis of the second α-1,4-glycosidic linkage to produce maltose (Peng et al. 2014). Branching enzyme alone and in combination with β-amylase were used to increase the amount of α-1,6 branching points, which are slowly hydrolyzed by mucosal α-glucosidases in the small intestine (Kittisuban et al. 2014).

As one of the earliest-found-enzymes, its evolution is always fascinating, not only because its roles are in clinical and industrial settings but also because a huge effort is being made in biotechnological industries to enhance amylase activity by modifying its structure. An interesting question is whether a human-modified amylase can survive with desired properties for generations in different species. An importance is whether a mutant can survive across species, i.e., when an amylase gene is cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli, can this foreign amylase gene function well in E. coli?

The analysis on the evolution of amylases can partially answer this question. Indeed, phylogenetics can reveal the evolutionary relationship entangled with human-modified amylases, and incorporation of large dataset can substantially enhance the revelation of phylogenetic analysis.

Additional approaches are still needed to answer this question. The first approach is to compute the average pairwise p-distance for each taxonomic group, which shows the diversity in each taxonomic group. A cloned and expressed amylase gene has a large chance to survive in a taxonomic group with a large average pairwise p-distance, because the previous observation showed that the larger the diversity is, the more the variants are (Darwin 1876). The second approach is to partition the variance into inter-clan and intra-clan variances with unequal size model II ANOVA, which tells whether a cloned and expressed amylases gene can easily survive in its own taxonomic group or in other taxonomic group. Theoretically, the average pairwise p-distance reveals the evolution in a multiple times manner and the partitioning of variance elucidates the horizontal gene transfer across species. It happens that these two approaches require the full taxonomic lineage from superkingdom, to kingdom, to phylum, to class, to order, to family, to genus and finally to species. Collectively, these three approaches can throw new insight into the evolution of amylases with respect to the abovementioned question.

Materials and methods

Data

When using amylase as a key searching word, two categories of amylases exist in UniProtKB, i.e., hydrolase and glycosidase. Thus, 4394 amylases under category of hydrolase and 4126 amylases under category of glycosidase were found in the UniProtKB. These 8520 amylases were all available amylases in UniProtKB for the release 2013_09—September 2013 and 2013_10—October 2013. After the deletion of identical amylases, 4721 amylases remained including 327 under the category of glycosidase, 852 under the category of hydrolase, and the rest 3542 under both categories of glycosidase and hydrolase.

The taxonomic lineage of the 4721 amylases was verified against the UniProtKB for release 2014_02. This verification found that 3398 amylases have fully documented taxonomic lineage from superkingdom, to kingdom, to phylum, to class, to order, to family, to genus, and finally to organism (Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). Hence, the 3398 amylases were used in this study. Of these 3398 amylases, 88 amylases come from archaea (Table S2 in Supplementary Materials) including two phyla (33 from Crenarchaeota and 55 from Euryarchaeota), seven classes (33 from Thermoprotei, 1 from Archaeoglobi, 14 from Halobacteria, 14 from Methanococci, 12 from Methanomicrobia, 13 from Thermococci and 1 from Thermoplasmata), 12 orders, 17 families and 35 genera; 724 amylases come from eukaryota (Table S2 in Supplementary Materials) including three kingdoms (53 from Fungi, 397 from Metazoa and 274 from Viridiplantae), 9 phyla, 23 classes, 46 orders, 83 families and 140 genera; 2586 amylases come from bacteria (Table S3 in Supplementary Materials) including 9 phyla, 18 classes, 41 orders, 67 families and 128 genera.

Of the 3398 amylases, 105 belong to the category of glycosidase, 359 belong to the category of hydrolase, 2934 belong to both categories of glycosidase and hydrolase, and 3118 are α-amylases and 280 are β-amylases. There are 88 α-amylases in archaea, 2545 α-amylases and 41 β-amylases in bacteria, and 485 α-amylases and 239 β-amylases in eukaryota.

Phylogenetic analysis

The sequence alignment was carried out using ClustalX (Larkin et al. 2007), which is a version with graphical user interface in Clustal series for multiple sequence alignment. The ClustalX performs multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix (Thompson et al. 1994). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using ClustalX with neighbor-joining method maximum likelihood, and presented using NJPlot (Perrière and Gouy 1996). The phylogenetic trees are statistically validated using 1000 bootstrap replicates in ClustalX. The default settings in ClustalX were chosen for operating ClustalX as recommended by software developers.

Statistical analysis

The pairwise p-distance was computed using Mega version 6.06 (Tamura et al. 2013) for each superkingdom, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family and genus, and then was presented in heatmaps. Although Mega software has the function of multiple sequence alignment using Clustal algorithm, our experience shows that its performance is not as good as ClustalX in pairwise sequence alignment, so the aligned sequences were input into Mega for computation of pairwise p-distance, which is the proportion (p) of amino acid sites at which two sequences being compared are different.

The average pairwise p-distance was furthermore partitioned in terms of intra-clan (within-clan) variance and inter-clan (between-clan) variance using unequal size model II ANOVA (Sokal and Rohlf 1995; Wu et al. 1999; Yan and Wu 2009, 2010a, b, 2011, 2013a, b).

Results

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic tree of 88 α-amylases from archaea. These amylases represent just a very small portion of amylases in the database, but the interests in them strongly exist because several species from archaea can survive in extreme environments, which could be potentially useful in biotechnological industries. For example, seven α-amylases belong to genus Thermococcus, which are hyperthermophilic archaea (Jeon et al. 2014), marked with red in Fig. 1. As can be seen, they evolved into two clusters at two extremes of phylogenetic tree. Moreover, these seven α-amylases have experienced different steps to reach the branches in the phylogenetic tree, so it is highly likely that these two clusters evolved independently and separately. The quantification of these different steps can be associated with the branch length in Fig. 1. As a result, the hyperthermophilic property in archaea is unlikely to be inherited vertically because of their two extreme locations in phylogenetic tree. On the other hand, the evolution of hyperthermophilic property in archaea could be attributed to the extreme environments, which would be the natural selection (Darwin 1876) for two extreme locations in phylogenetic tree.

Phylogenetic tree of 88 α-amylases from archaea. The numbers along each branch and scale bar represent the branch length, which is the number of substitutions per unit time (Tamura et al. 2013). Seven α-amylases from genus Thermococcus were marked in red and four α-amylases from genus Haloarcula were marked in green

Another property is that haloarchaeal amylases have lower propensity for helix formation but higher propensity for coil formation, which keeps amylases being active in high salt concentration through highly negative charged surface with over representation of acidic residues (Liu et al. 2011; Zorgani et al. 2014). This haloadaptation in hypersaline environments can be tracked in Fig. 1 marked in green, where three amylases (G0HQH8, Q4A3E0 and M0KQ22) from Haloarcula clustered together whereas an amylase from Haloarcula marismortui evolved independently. However, two amylases from Haloarcula hispanica did evolve together, which is a piece of evidence of vertical inheritance for haloadaptation in archaea.

Figure 2 displays the average pairwise p-distance of amylases for each phylum, class, order, family and genus in archaea. For example, the average p-distance for each of 33 amylases from phylum Crenarchaeota is 0.6407, which is the mean value of p-distance for any single amylase versus the rest 32 amylases. In fact, the average p-distance indicates the divergence of amylases in each taxonomic group, which nevertheless varies greatly across taxonomic groups. For instance, the average p-distance is statistically smaller in phylum Crenarchaeota than in phylum Euryarchaeota (0.6407 ± 0.1228, n = 33 vs. 0.7794 ± 0.0677, n = 55, mean ± SD, p < 0.001).

Again, attention can be paid to the average p-distance in genus Thermococcus, which is an example discussed in Fig. 1. Genus Thermococcus can be found in the next to the bottom entry in the right-hand of Fig. 2 and its average p-distance is 0.5604, which is smaller than the average p-distances of family, order, class and phylum that genus Thermococcus belongs to. This provides additional information of why the amylases from genus Thermococcus evolved into two clusters in Fig. 1. It is because genus Pyrococcus, whose average p-distance is 0.6313, from the same family Thermococcaceae also evolved into two clusters. Similarly, Fig. 2 gives the clue to find out why some genera have different average p-distances from their belonging family, order, class and phylum.

Figures 1 and 2 already suggest the way to track the flow of genetic materials of amylases, which can transmit both vertically and horizontally. When the variance of p-distance is partitioned into inter-clan and intra-clan variances, then new insight can be obtained. Figure 3 illustrates inter-clan and intra-clan variances of archaea amylases, and emphasizes whether the evolution of amylases is likely to be constrained within genus, family, order, and class or across them. This figure can be read as follows: the amylases from archaea (superkingdom) come from two phyla Crenarchaeota (upper line) and Euryarchaeota (lower line), and the data from phylum Euryarchaeota were allowed to compute the inter-class variance (83.98 %) and the intra-class variance (16.02 %), which were marked as dark and bright portions in the pie. The amylases from Thermoprotei (upper line at class level) come from four orders, Acidilobales, Desulfurococcales, Sulfolobales and Thermoproteales, of which the inter-order and intra-order variances are 2.01 and 97.99 %. The haloadaptation discussed in Fig. 1 is relevant to family Halobacteriaceae, and now Fig. 3 delineates its inter-genus and intra-genus variances into 42.78 and 57.22 % in green colored pie. In this circumstance, the haloadaptation in archaea is more likely to occur within family Halobacteriaceae because of its large intra-genus variance.

Partitioning of p-distance into inter-clan and intra-clan variances for α-amylases from archaea along taxonomic linkage. The bifurcation is the point across taxonomic boundary. Pies show the inter-clan variance (dark color) and intra-clan variance (bright color). The green and deep green pie is an example discussed in “Results section”. Taxonomic names can be found in Supplementary Material Table S2

Figure 4 demonstrates the phylogenetic tree of 724 amylases from eukaryota. Since the portion of β-amylases in eukaryota (485 α-amylases vs. 239 β-amylases) is far higher than that in bacteria (2545 α-amylases vs. 41 β-amylases), it is interesting and important to figure out how β-amylases co-evolved with α-amylases. Figure 4 provides the clear evidence that β-amylases evolved separately from α-amylases because 235 of 239 β-amylases were exclusively clustered together without any entanglement of α-amylases although two α-amylases, M5CEF1 and M5C2U3, stand at the very top of phylogenetic tree. Similarly distinct phylogenetic branch was also found in Aspergillus affinis in the past (Davolos and Pietrangeli 2014). The only possible co-evolution can be noticed for four β-amylases, M0WHZ4, C3W8N8, M1MQ51 and P30271, mixed with α-amylases in the lower part of phylogenetic tree.

Full phylogenetic tree of 724 amylases from eukaryota. β-amylases distribute in the upper cluster marked in red bar, and only 4 β-amylases scatter among α-amylases in the bottom indicated by red line. The full phylogenetic tree in Newick format with maximum likelihood bootstrap values on all branches is available in supplementary materials

Figure 5 pictures the average p-distance of amylases for each kingdom, phylum, class, order, family and genus in eukaryota. As a matter of fact, it is only kingdom Viridiplantae that has β-amylases, i.e., all 239 β-amylases come from the 274 amyalses in kingdom Viridiplantae. Comparisons among Viridiplantae, Fungi and Metazoa result in no statistical difference between Viridiplantae and Metazoa (0.3929 ± 0.2107, n = 274 versus 0.3924 ± 0.0693, n = 397, mean ± SD, p = 0.9632) but statistical difference between Viridiplantae and Fungi (0.3929 ± 0.2107, n = 274 versus 0.7017 ± 0.1251, n = 53, mean ± SD, p < 0.001). Given these results, the co-evolution of β-amylases with α-amylases did not significantly influence the diversity of amylases in kingdom Viridiplantae.

Figure 6 exhibits the partitioning of variance of p-distance into inter-clan and intra-clan variances in eukaryota. The four β-amylases, M0WHZ4, C3W8N8, M1MQ51 and P30271, which were mixed with α-amylases in the lower part of phylogenetic tree in Fig. 4, belong to four different genera Hordeum, Hordeum, Triticum and Secale, but the same family Poaceae, whose inter-genus and intra-genus variances are 46.23 and 53.77 % marked in blue colored pie at the bottom of Fig. 6. Thus, the evolution of these four β-amylases could partially be explained as horizontal gene transfer together with vertical gene transfer.

Partitioning of p-distance into inter-clan and intra-clan variances for α-amylases from eukaryota along taxonomic linkage. The bifurcation is the point across taxonomic boundary. Pies show the inter-clan variance (dark color) and intra-clan variance (bright color). The blue and deep blue pie is an example discussed in “Results section”. Taxonomic names can be found in Supplementary Material Table S2

Figure 7 highlights the phylogenetic tree of 2586 amylases from bacteria. As seen in Panel A of Fig. 7, the amylases from E. coli (marked in red) were formed into two major clusters. It is difficult to determine how many generations of E. coli have evolved prior to these two clusters because man-made manipulation could occur at any step of bacterial evolution. However, the incorporated amylase gene into E. coli could serve as an indicator to follow the gene flow along the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 7. In Panel B of Fig. 7, a single amylase came from species Escherichia sp 3_2_53FAA, C1HLV3, marked in pink color in lower middle position of vertical bar. Meanwhile, there were 23 amylases from genus Shigella, E7SH51, K0XRX9, F3VVM2, E7TEQ3, B2TXH1, F3WGB6, E7JWB2, J2G2S2, E2XIT9, F5N3D5, F5QZG9, F5Q6I0, E3Y0F3, F5PSD3, F5PCB5, F5MNJ8, F5NHN6, F5NVY7, F5QKU4, F7RA14, J2FWI3, E7SRQ3 and F4NER9, marked in green color along vertical bar. These 24 amylases entangled with the amylases from E. coli represent an example of horizontal gene transfer because their phylogenetic branches came from a single source at the bottom of Panel B. By contrast, an alternative situation can be noted in comparison of Panel C with Panel B, it turns out few amylases from E. coli. In Panel D of Fig. 7, thirty-one amylases belong to genus Shigella, including E7T4J5, F3WPB1, I6CZI8, F3VDI0, B3WVA3, I6B666, F5NA02, I6CAN4, E2X920, E2X919, B2U552, I6GAP5, E7SHS0, I6DLH4, E7T6D5, I6BAI4, F3W3Y2, I6B957, F5QRA0, F5QCV8, F5PYL1, F5MV99, E3Y7M8, I6FJK9, I6CKM0, F5NNG9, F5PIN8, F5P2G0, F5NA01, I6B5V3, F5P2G1, which were marked in green bars. The explanation for Panel B can be applied to these 31 amylases, e.g. the horizontal gene transfer could occur to get some genetic materials from E. coli, and afterwards they were clustered with E. coli together.

Phylogenetic tree of amylases from bacteria. Panel a is the full phylogenetic tree of 2586 amylases from bacteria, where the amylases marked in red belong to E. coli. Panel b is a detailed portion of phylogenetic tree of amylases from E. coli (red bars) and from genus Shigella (green bars). Panel c is a detailed portion of phylogenetic tree of amylases from phyla Armatimonadetes, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria were marked in orange, black, dark green and pink bars, respectively. Panel d is a detailed portion of phylogenetic tree of amylases from E. coli (red bars) and from genus Shigella (green bars). The full phylogenetic tree in Newick format with maximum likelihood bootstrap values on all branches is available in supplementary materials

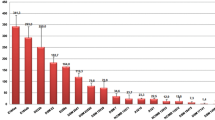

Figure 8 depicts the average pairwise p-distance of amylases for each phylum, class, order, family and genus in bacteria. It was observed that just a small portion of bacterial diversity can be cultured in laboratory condition (Vester et al. 2014). One might expect to see a small average pairwise p-distance under human manipulations. This expectation is true because E. coli belonged to genus Escherichia, family Enterobacteriaceae, order Enterobacteriales, whose average p-distance is smaller than that in other genera, families and orders as seen in light green color and blue color in the lower part of Fig. 8.

Figure 9 outlines the partitioning of variance of p-distance into inter-clan and intra-clan variances in bacteria. A follow-up question on engineered E. coli is to analyze its inter-clan and intra-clan variances in order to reveal whether man-made manipulation keeps E. coli functioning. As seen the gray pie in Fig. 9, the inter-genus variance in family Enterobacteriaceae is 31.60 %, to which E. coli belongs. This inter-genus variance is indeed not large, so man-made manipulation in E. coli has a large probability to survive from generation to generation in biotechnological industries.

Partitioning of p-distance into inter-clan and intra-clan variances for α-amylases from bacteria along taxonomic linkage. The bifurcation is the point across taxonomic boundary. Pies show the inter-clan variance (dark color) and intra-clan variance (bright color). The gray and black pie is an example discussed in “Results section”. Taxonomic names can be found in Supplementary Material Table S

Figure 10 describes the full phylogenetic tree of 3398 amylases (left panel). Basically, many interesting evolutionary traces can be tracked in Fig. 10, however emphasis is given to archaea that were marked in red for the sake of space. As seen in the right panel in Fig. 10, the evolution of amylases may undergo vertical and horizontal gene transfer, multiple times and multiple clans, which is evident in light of the coexisting of amylases from archaea, bacteria and eukaryota. Also, glycoside hydrolase family 57 (GH57) contains α-amylases mainly from archaea and bacteria (Janeček and Blesák 2011), in turn this suggests the close relationship of α-amylases between archaea and bacteria. These issues are equally important for bacteria. For example, Halothermothrix orenii, which belongs to genus Halothermothrix, family Halanaerobiaceaes, order Halanaerobiales, class Clostridia, phylum Firmicutes, is an anaerobe for gluconeogenesis and fermentation of ethanol and acetate, whose thermohalophiles are crusial for the conversion of starch into bioethanol (Bhattacharya and Pletschke 2014). There are two amylases from H. orenii, M5E0T3 and B8CWQ7, whose locations are far away in the full phylogenetic tree of 3398 amylases as colored in purple. Although these two amylases belong to the same genus, they clearly evolved in a manner of multiple times as demonstrated by purple arrows at the bottom of Fig. 10.

Overall evolution of amylases from archaea, bacteria and eukaryota. Full phylogenetic tree of 3398 amylases was shown in left panel. The amylases from archaea were marked with red, of which part phylogenetic trees showed the detail distribution in the right panels. The detail distribution of two amylases from Halothermothrix orenii was shown in bottom. The amylases from archaea, bacteria and eukaryota were marked with red, black and green bars, respectively. The full phylogenetic tree in Newick format with maximum likelihood bootstrap values on all branches is available in supplementary materials

Discussion

In this study, both phylogenetic and statistical approaches are applied to analyze the evolution of amylases, which are characterized by vertical and horizontal gene transfer, and multi-time and multi-clan evolution.

Different average p-distances give a whole picture on the evolutionary history of amylases, i.e., the larger is the average p-distance in a taxonomic group, the larger is the probability that a species acquires or loses genetic materials from other group, whereas the smaller is the average p-distance in a taxonomic group, the larger is the probability that a species acquires its genetic materials vertically. Nevertheless, different average p-distances can be affected by various factors, notably random factors, such as selection of samples. In addition, a small average p-distance suggests that a later expansion of amylases in a certain taxonomic group. For example, the average p-distance in class Methanococci (blue color block in column class in Fig. 2) is 0.3303, which is smaller than those in other taxonomic classes.

Obviously, the larger the inter-clan variance is, the larger the probability is that the evolution would likely cross the taxonomic boundary line. Although the available data are not sufficient to compute inter-clan and intra-clan variances for all taxonomic groups, what was computed indicates that inter-clan variance in archaea is generally not large because dark portions do not account for a major portion in each pie. Really, inter-clan variance can be referenced to the horizontal gene transfer because it represents the chance to pass the genetic materials across taxonomic boundary line.

It ends up with the co-evolution of β-amylases and α-amylases in kingdom Viridiplantae, for the reason that their average p-distance did not change too much within kingdom Viridiplantae. Oppositely, the average p-distance in phylum Chlorophyta changed significantly (brown color in Fig. 5), whose ratio of α-amylases versus β-amylases is 4/5, and definitely this increase in average p-distance cannot be attributed to either α-amylases or β-amylases. In the past, co-evolution was observed in fungus-gardening insects because their lineages shared fungal symbionts with microbes, and co-evolution thus appeared diffuse co-evolutionary relationships, while microbes exhibit none of symbiont sharing, resulting in host-fungus fidelity (Kooij et al. 2014; Seal et al. 2014).

In the analysis on eukaryota amylases, the hypothesis that takes into consideration is an ontogenetic dietary shift from carnivory to herbivory or omnivory, for which family Stichaeidae was defined (German et al. 2014). Two species from family Stichaeidae, A0FCQ3 and A0FCQ5, were neighbored with D3TJK0, Q5EMQ2, Q8QGJ0, G5EMQ0 and G5EMQ1 from the same order Perciformes, and Q9I9H5 from a neighboring order Pleuronectiformes, therefore these evolutionary branches in phylogenetic tree could together evolve according to this hypothesis. The lineage-specific expansions were partly driven by directional selection, and gains and losses of genes were lineage dependent (Da Lage et al. 2013). In realty, the intestine environment also plays a role in positive selections of fungal α-amylase in ants (Bacci et al. 2013) as witnessed in local diet (Linton et al. 2014), and gene encoding amylases in marine yeasts versus terrestrial yeasts (Chi et al. 2009).

For the evolution of amylases from bacteria, particular attention is paid to the amylases from E. coli, because E. coli is not capable to use starch as its carbon source (Rosales-Colunga and Martínez-Antonio 2014) and belongs to non-probiotic bacteria such as Enterobacter aerogenes (Das et al. 2014), therefore the involvement of E. coli in amylase evolution is mainly driven by the fact that amylase gene was cloned and expressed in E. coli because E. coli is one of the most widely used microorganisms in biotechnological industries (Tao et al. 2008). This manipulation certainly changes the gene pool in bacteria because 24.05 % (622/2586) amylases come from E. coli in the database used in this study. On the other hand, Lactobacillus, a genus of probiotic bacteria, is also a bacterium that is cloned and expressed for secreting amylase (Kim et al. 2008; Yoon et al. 2008). Over here, the question is how an amylase gene was incorporated into E. coli. This could be explained in two ways: (1) These gene transfers were facilitated by human manipulation because the amylases in E. coli come from four phyla Armatimonadetes, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria. (2) These gene transfers come from the horizontal gene transfer because of tight contact of E. coli with other bacteria in particular environments.

In a broad sense, the study on the evolution of amylases is equal to the study on the evolution of conserved regions in amylases. For example, (α/β) 8 barrel is a conserved the region (Hleap et al. 2013). For another example, α-amylase is a calcium-dependent metalloenzyme whose calcium ion binding regions are subject to evolutionary insertions and deletions (Singh and Guruprasad 2014), so several hypotheses were proposed on gene acquisitions and deletions (Minaya et al. 2013). However, the conversed regions in amylase might have been impacted by the effort in development of inhibitory substances on α-amylase. For instance, Phyllostachys edulis produces an inhibitory substance (Yang et al. 2014) and SbAI is an inhibitory gene in potato (Zhang et al. 2014). Still, the access to high- and low-starch diets impacts the evolution of amylase as demonstrated by the number of amylase gene copies (Perry et al. 2007; Santos et al. 2012; Freedman et al. 2014).

It would not be expected that phylogenetic tree would branch in good agreement with taxonomic lineage because recent taxonomic classifications are based on 16s rRNA gene sequences (Krishnan et al. 2012; Sahay et al. 2013; Subhash et al. 2014), while phenotype often results from biochemical tests for amylase (Blackburn et al. 2013). For example, maltose is the main product of starch hydrolysis and an indicator of β-amylase activity (Li and Yu 2012). In this study, the analysis based on amylase taxonomic classification is reasonable because amylolytic enzymes in family GH13 are classified into four groups, i.e., heterologous α-amylase, eukaryotic α-amylases, bacterial and fungal α-amylase and GH13 α-glucosidases (Chen et al. 2012). For this reason, pullulanase whose crystal structure looks like a typical α-amylase structure (Zhen et al. 2014) is not included in this study.

Our data are far from complete if we consider how many species could exist in each superkingdom. The availability of detailed taxonomic lineage imposes the limit for any large-scale studies on the evolution of amylases, and a resultant consequence is the unbalance in available data in each superkingdom, phylum, class, order, family and genus. To a certain degree, this unbalance could cause different interpretations for Figs. 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 and 9. At different taxonomic level, divergence is different. For example, the colors at superkingdom level in Figs. 2, 5 and 8 are quite similar, suggesting a similar rate of mutations in consistent with molecular clock. But the colors at genus level in Figs. 2, 5 and 8 are very different, confirming the difference in lifespan between bacteria/archaea and eukaryota. For Figs. 3, 6, and 9, the partition of variance stratifies variance into vertical and horizontal gene transfers, of which the horizontal gene transfer is primary concern. For various reasons, the horizontal gene transfer depends on many factors, while our analysis concentrates on the horizontal gene transfer within a superkingdom with the hope that model II ANOVA could serve as a method to quantify vertical and horizontal gene transfers.

In this study, we explore the general pattern of amylase evolution with the hope to potentially enhance the successful rate of cloning and expression of amylase gene in different species by employing phylogenetic and statistical approaches to a large dataset. The phylogenetic tree, diversity of average pairwise p-distance and its partitions would be helpful for the engineering of new amylases.

References

Bacci M, Bueno OC, Rodrigues A, Pagnocca FC, Somera AF, Silva A (2013) A metabolic pathway assembled by enzyme selection may support herbivory of leaf-cutter ants on plant starch. J Insect Physiol 59:525–531

Bharathi A, Roopan SM, Vasavi CS, Munusami P, Gayathri GA, Gayathri M (2014) In silico molecular docking and in vitro antidiabetic studies of dihydropyrimido[4,5-α]acridin-2-amines. Biomed Res Int 2014:971569

Bhattacharya A, Pletschke BI (2014) Review of the enzymatic machinery of Halothermothrix orenii with special reference to industrial applications. Enzyme Microb Technol 55:159–169

Blackburn MB, Martin PA, Kuhar D, Farrar RR, Gundersen-Rindal DE (2013) Phylogenetic distribution of phenotypic traits in Bacillus thuringiensis determined by multilocus sequence analysis. PLoS One 8:e66061

Chen W, Xie T, Shao Y, Chen F (2012) Phylogenomic relationships between amylolytic enzymes from 85 strains of fungi. PLoS One 7:e49679

Chi Z, Zhang T, Liu G, Li J, Wang X (2009) Production, characterization and gene cloning of the extracellular enzymes from the marine-derived yeasts and their potential applications. Biotechnol Adv 27:236–255

Da Lage JL, Binder M, Hua-Van A, Janeček S, Casane D (2013) Gene make-up: rapid and massive intron gains after horizontal transfer of a bacterial α-amylase gene to Basidiomycetes. BMC Evol Biol 13:40

Darwin C (1876) The origin of species by means of natural selection or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life, 6th edn. John Murray, London

Das D, Baruah R, Goyal A (2014) A food additive with prebiotic properties of an α-d-glucan from Lactobacillus plantarum DM5. Int J Biol Macromol 69:20–26

Davolos D, Pietrangeli B (2014) A molecular and bioinformatic study on the ochratoxin A (OTA)-producing Aspergillus affinis (section Circumdati). Mycotoxin Res 30:113–122

Deng Z, Yang H, Shin HD, Li J, Liu L (2014) Structure-based rational design and introduction of arginines on the surface of an alkaline α-amylase from Alkalimonas amylolytica for improved thermostability. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:8937–8945

Dey TB, Banerjee R (2014) Application of decolourized and partially purified polygalacturonase and α-amylase in apple juice clarification. Braz J Microbiol 45:97–104

Elsayed G, Cheung M, Mansoor M, Tonkin J, Lindo D, Gertner D, Subhani J (2014) PTH-039 Preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ercp) pancreatitis: changing practice at a district general hospital. Gut 63(Suppl 1):A225–A226

Fishman JE, Levy G, Alli V, Zheng X, Mole DJ, Deitch EA (2014) The intestinal mucus layer is a critical component of the gut barrier that is damaged during acute pancreatitis. Shock 42:264–270

Freedman AH, Gronau I, Schweizer RM, Ortega-Del Vecchyo D, Han E, Silva PM, Galaverni M, Fan Z, Marx P, Lorente-Galdos B, Beale H, Ramirez O, Hormozdiari F, Alkan C, Vilà C, Squire K, Geffen E, Kusak J, Boyko AR, Parker HG, Lee C, Tadigotla V, Siepel A, Bustamante CD, Harkins TT, Nelson SF, Ostrander EA, Marques-Bonet T, Wayne RK, Novembre J (2014) Genome sequencing highlights the dynamic early history of dogs. PLoS Genet 10:e1004016

German DP, Gawlicka AK, Horn MH (2014) Evolution of ontogenetic dietary shifts and associated gut features in prickleback fishes (Teleostei: Stichaeidae). Comp Biochem Physiol B: Biochem Mol Biol 168:12–18

Gupta M, Sharma P, Nath AK (2014) Purification of a novel α-amylase inhibitor from local Himalayan bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) seeds with activity towards bruchid pests and human salivary amylase. J Food Sci Technol 51:1286–1293

Hernández Garcés HR, Almeida Linnet A, Abreu Vã Zquez MA, Calzadilla Bertot L, Peà AK, Andrain Sierra Y, Moutary I, Segura Fernà Ndez N (2014) Risk factors associated with the development of hyperamylasemia and post-ERCP pancreatitis in the Cuban National Institute. Rev Gastroenterol Peru 34:127–132

Hleap JS, Susko E, Blouin C (2013) Defining structural and evolutionary modules in proteins: a community detection approach to explore sub-domain architecture. BMC Struct Biol 13:20

Janeček S, Blesák K (2011) Sequence-structural features and evolutionary relationships of family GH57 α-amylases and their putative α-amylase-like homologues. Protein J 30:429–435

Jeon EJ, Jung JH, Seo DH, Jung DH, Holden JF, Park CS (2014) Bioinformatic and biochemical analysis of a novel maltose-forming α-amylase of the GH57 family in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus sp. CL1. Enzyme Microb Technol 60:9–15

Jianhua L, Weiguang X, Abdullahi AY, Fan W, Qin A, Dingyuan F, Jianjun Z (2014) Purification and partial characterization of an acidic α-amylase from a newly isolated Bacillus subtilis zj-1 that may be applied to feed enzyme. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 45:259–267

Kim JH, Sunako M, Ono H, Murooka Y, Fukusaki E, Yamashita M (2008) Characterization of gene encoding amylopullulanase from plant-originated lactic acid bacterium, Lactobacillus plantarum L137. J Biosci Bioeng 106:449–459

Kittisuban P, Lee BH, Suphantharika M, Hamaker BR (2014) Slow glucose release property of enzyme-synthesized highly branched maltodextrins differs among starch sources. Carbohydr Polym 107:182–191

Koh D (2014) Use of salivary biomarkers to evaluate response to a stress management intervention. Occup Environ Med 71(Suppl 1):A109

Kooij PW, Liberti J, Giampoudakis K, Schiøtt M, Boomsma JJ (2014) Differences in forage-acquisition and fungal enzyme activity contribute to niche segregation in Panamanian leaf-cutting ants. PLoS One 9:e94284

Krishnan P, Bhat R, Kush A, Ravikumar P (2012) Isolation and functional characterization of bacterial endophytes from Carica papaya fruits. J Appl Microbiol 113:308–317

Kumar P, Pant DC, Mehariya S, Sharma R, Kansal A, Kalia VC (2014) Ecobiotechnological strategy to enhance efficiency of bioconversion of wastes into hydrogen and methane. Indian J Microbiol 54:262–267

Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948

Li X, Yu HY (2012) Purification and characterization of novel organic-solvent-tolerant β-amylase and serine protease from a newly isolated Salimicrobium halophilum strain LY20. FEMS Microbiol Lett 329:204–211

Linton SM, Saborowski R, Shirley AJ, Penny JA (2014) Digestive enzymes of two brachyuran and two anomuran land crabs from Christmas Island, Indian Ocean. J Comp Physiol B 184:449–468

Liu B, Tang S, Ming H, He S, Nie G, Guan T, Zhang L, Li W (2011) Biodiversity and functional enzymes of cultured Halophilic archaeon in Lop Nur region. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 51:1222–1231

Minaya M, Pimentel M, Mason-Gamer R, Catalan P (2013) Distribution and evolutionary dynamics of stowaway miniature inverted repeat transposable elements (MITEs) in grasses. Mol Phylogenet Evol 68:106–118

Partelli S, Tamburrino D, Crippa S, Facci E, Zardini C, Falconi M (2014) Evaluation of a predictive model for pancreatic fistula based on amylase value in drains after pancreatic resection. Am J Surg 208(4):634–639

Peng T, Zhu X, Duan N, Liu JH (2014) PtrBAM1, a β-amylase-coding gene of Poncirus trifoliata, is a CBF regulon member with function in cold tolerance by modulating soluble sugar levels. Plant Cell Environ 37:2754–2767

Perrière G, Gouy M (1996) WWW-Query: an on-line retrieval system for biological sequence banks. Biochimie 78:364–369

Perry GH, Dominy NJ, Claw KG, Lee AS, Fiegler H, Redon R, Werner J, Villanea FA, Mountain JL, Misra R, Carter NP, Lee C, Stone AC (2007) Diet and the evolution of human amylase gene copy number variation. Nat Genet 39:1256–1260

Pervez S, Aman A, Iqbal S, Siddiqui NN, Ul Qader SA (2014) Saccharification and liquefaction of cassava starch: an alternative source for the production of bioethanol using amylolytic enzymes by double fermentation process. BMC Biotechnol 14:49

Podsędek A, Majewska I, Redzynia M, Sosnowska D, Koziołkiewicz M (2014) In vitro inhibitory effect on digestive enzymes and antioxidant potential of commonly consumed fruits. J Agric Food Chem 62:4610–4617

Raul D, Biswas T, Mukhopadhyay S, Kumar Das S, Gupta S (2014) Production and partial purification of alpha amylase from Bacillus subtilis (MTCC 121) using solid state fermentation. Biochem Res Int 2014:568141

Rosales-Colunga LM, Martínez-Antonio A (2014) Engineering Escherichia coli K12 MG1655 to use starch. Microb Cell Fact 13:74

Sahay H, Babu BK, Singh S, Kaushik R, Saxena AK, Arora DK (2013) Cold-active hydrolases producing bacteria from two different sub-glacial Himalayan lakes. J Basic Microbiol 53:703–714

Santos JL, Saus E, Smalley SV, Cataldo LR, Alberti G, Parada J, Gratacòs M, Estivill X (2012) Copy number polymorphism of the salivary amylase gene: implications in human nutrition research. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics 5:117–131

Schomburg I, Chang A, Placzek S, Söhngen C, Rother M, Lang M, Munaretto C, Ulas S, Stelzer M, Grote A, Scheer M, Schomburg D (2013) BRENDA in 2013: integrated reactions, kinetic data, enzyme function data, improved disease classification: new options and contents in BRENDA. Nucleic Acids Res 41:764–772

Seal JN, Schiøtt M, Mueller UG (2014) Ant-fungus species combinations engineer physiological activity of fungus gardens. J Exp Biol 217(Pt 14):2540–2547

Singh S, Guruprasad L (2014) Structure and sequence based analysis of alpha-amylase evolution. Protein Pept Lett 21:948–956

Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ (1995) Biometry: the principles and practices of statistics in biological research, 3rd edn. W. H. Freeman, New York, pp 203–218

Sole ML, Conrad J, Bennett M, Middleton A, Hay K, Ash-Worth S, Mehta DI (2014) Pepsin and amylase in oral and tracheal secretions: a pilot study. Am J Crit Care 23:334–338

Subhash Y, Sasikala C, Ramana CV (2014) Salinimicrobium sediminis sp. nov., isolated from a deep-sea sediment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64(Pt 3):984–988

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S (2013) MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729

Tao X, Jang MS, Kim KS, Yu Z, Lee YC (2008) Molecular cloning, expression and characterization of alpha-amylase gene from a marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas sp. MY-1. Indian J Biochem Biophys 45:305–309

The UniProt Consortium (2010) The universal protein resource (UniProt) in 2010. Nucleic Acids Res 38:D142–D148

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22:4673–4680

Tiwari AK (2014) Revisiting “Vegetables” to combat modern epidemic of imbalanced glucose homeostasis. Pharmacogn Mag 10(Suppl 2):S207–S213

Tzuc JT, Escalante DR, Rojas Herrera R, Gaxiola Cortés G, Ortiz ML (2014) Microbiota from Litopenaeus vannamei: digestive tract microbial community of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Springerplus 3:280

Vester JK, Glaring MA, Stougaard P (2014) Discovery of novel enzymes with industrial potential from a cold and alkaline environment by a combination of functional metagenomics and culturing. Microb Cell Fact 13:72

Voskuil MD, Mittal S, Sharples EJ, Vaidya A, Gilbert J, Friend PJ, Ploeg RJ (2014) Improving monitoring after pancreas transplantation alone: fine-tuning of an old technique. Clin Transplant 28:1047–1053

Wu G, Baraldo M, Furlanut M (1999) Inter-patient and intra-patient variations in the baseline tapping test in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Belg 99:182–184

Wulan DR, Utomo EP, Mahdi C (2014) Molecular modeling of Ruellia tuberosa L compounds as a-amylase inhibitor: an in silico comparation between human and rat enzyme model. Bioinformation 10:209–215

Yan S, Wu G (2009) Rationale for cross-species infection and cross-subtype mutation in hemagglutinins from influenza A virus. Interdiscip Sci Comput Life Sci 1:303–307

Yan S, Wu G (2010a) Evidence for cross-species infection and cross-subtype mutation in influenza a matrix proteins. Viral Immunol 23:105–111

Yan S, Wu G (2010b) Evidence obtained from ANOVA to reason cross-species infection and cross-subtype mutation in neuraminidases of influenza A viruses. Transbound Emerg Dis 57:254–261

Yan S, Wu G (2011) Possible reason for cross-species and cross-subtype reassortment in polymerase basic protein 2 from influenza A virus. Protein Pept Lett 18:434–439

Yan S, Wu G (2013a) Possibility of cross-species/subtype reassortments in influenza A viruses: an analysis on nonstructural protein variations. Virulence 4:716–725

Yan S, Wu G (2013b) Small variations between species/subtypes attributed to reassortment evidenced from polymerase basic protein 1 with other seven proteins from influenza A virus. Transbound Emerg Dis 60:110–119

Yang JP, He H, Lu YH (2014) Four flavonoid compounds from Phyllostachys edulis leaf extract retard the digestion of starch and their working mechanisms. J Agric Food Chem 62:7760–7770

Yoon SW, Lee CH, Kim JY, Sung MH, Poo H (2008) Lactobacillus casei secreting alpha-MSH induces the therapeutic effect on DSS-induced acute colitis in Balb/c Mice. J Microbiol Biotechnol 18:1975–1983

Zaferanloo B, Bhattacharjee S, Ghorbani MM, Mahon PJ, Palombo EA (2014) Amylase production by Preussia minima, a fungus of endophytic origin: optimization of fermentation conditions and analysis of fungal secretome by LC-MS. BMC Microbiol 14:55

Zhang H, Liu J, Hou J, Yao Y, Lin Y, Ou Y, Song B, Xie C (2014) The potato amylase inhibitor gene SbAI regulates cold-induced sweetening in potato tubers by modulating amylase activity. Plant Biotechnol J 12:984–993

Zhen J, Hu Z, Li S, Xu J, Song H (2014) Structure and function of a novel thermostable pullulanase. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 30:119–128

Zorgani MA, Patron K, Desvaux M (2014) New insight in the structural features of haloadaptation in α-amylases from halophilic Archaea following homology modeling strategy: folded and stable conformation maintained through low hydrophobicity and highly negative charged surface. J Comput Aided Mol Des 28:721–734

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by research Grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31460296 and 31560315), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2013GXNSFDA019007), Guangxi Scientific and Technological Cooperation and Exchange Program (1347004-1) and Special Funds for Building of Guangxi Talent Highland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, S., Wu, G. Analysis on evolutionary relationship of amylases from archaea, bacteria and eukaryota. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 32, 24 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-015-1979-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-015-1979-y