Abstract

The calix[4]resorcinarene macrocycles are excellent oligomers for the design of amphiphilic derivatives; they can form self-assemblies and stable sensing networks. Owing to their favorable properties, they are the focus of many exploitations and studies ranging from biological controls to heavy metal ion sensing. In this perspective, two calix[4]resorcinarene derivatives, namely: C-dec-9-en-1-ylcalix[4]resorcinarene (ionophore I) and C-undecylcalix[4]resorcinarene (ionophore II) were used to form stable ultra-thin Langmuir monolayer films at the air/water interface; their interactions with different harmful metal cations (Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, and Cu2+) were studied and highlighted via the pressure-area (Π-A) isotherms. The obtained results in the current investigation showed a dependence of both macrocycle interactions on the metal cation concentration in the subphase, confirming their complexation. In addition, the ionophore (I) exhibited high selectivity towards Pb2+ and Cu2+ cations, whereas the ionophore (II) showed tendency to bind with Cu2+ cations over others, approving the potential applicability of these macrocycles as ion selective chemical sensors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Heavy metal (HM) ion poisoning is a vital threat to the environment, affecting hazards ranging from environmental pollution to human toxicity. HM ion toxic exposure occurs by means of environmental contaminations, medical treatments, industrial production, and accidents (Eddaif et al. 2019a). The low atomic mass metals (Cu and Zn) frequently play important roles in cell physiology, thus are required for the human body. HM such as Pb, Hg, and/or Cd forms stable coordination complexes with thiol groups, leading to important biological perturbations including DNA alterations, biotransformations, renal, cerebral, or even liver poisoning, accordingly; as a result, the necessity of special early detection and monitoring techniques is of enormous importance in environmental analysis (Eddaif et al. 2019a). Currently, a variety of metal ion detection methods are employed including conventional (ICP-MS, AAS, or ICP-OES) and non-conventional (ion selective electrodes, chemical sensors…etc.), the later techniques tend to be more practical in terms of cost, time, sensitivity, and selectivity, as well as usage simplicity (Eddaif et al. 2019a).

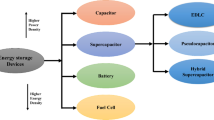

The environmental control of these toxicants based on ion selective electrodes or chemical sensors was hugely investigated, by means of electrode functionalization with various selective membranes comprising biological (DNA, proteins) (Chao et al. 2012; Neupane et al. 2016; Ravikumar et al. 2016; Xiang and Lu 2014; Xiao et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2019, 2011), nanostructural (carbon nanotubes, graphene oxides) (Gong et al. 2014; Park et al. 2017; Shtepliuk et al. 2017; Xuan and Park 2017; Xuan et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2018a, b), and macrocyclic chemical sensing platforms (cyclodextrines, crownethers, calixarenes, and resorcinarenes) (Alam et al. 2019; Eddaif et al. 2019a, b, c; Maeda et al. 2008; Nur Abdul Aziz et al. 2018; Pizarro et al. 2019; Prochowicz et al. 2017; Puccini et al. 2018). The calixarenes/resorcinarenes are well-known third-generation macrocyclic compounds (Fig. 1), commonly produced via base-induced cyclocondensation of aldehydes with phenols/resorcinols, and mainly used in molecular recognition as selective receptors for cations, anions, as well as neutral molecules; their receptor or complexing host-guest properties are typically due to their amphiphilic nature (hydrophobic upper rim and hydrophilic lower rim) (Eddaif et al. 2019a, d).

The first validation step of the sensing platform’s (e.g., calix[4]resorcinarene macrocycles) applicability manifests in performing some preliminary examinations (e.g., Langmuir monolayers and surface pressure-area isotherms) in order to improve its surface activities from one side and to be sure of the potential interactions, which will occur between it and the target detection analytes from another side. Therefore, it is of huge importance to initially investigate the calix[4]resorcinarenes monolayer behavior on subphases containing various HM (in case of metal ion monitoring), before direct applications for detection purposes, since studying such ultrathin films can offer perceptions on the intra or even intermolecular interactions happening between the sensing platform and the metallic toxicants (Davis et al. 1998; Davis and Stirling 1996; Moreira et al. 1994; Shahgaldian et al. 2005; Supian et al. 2010; Torrent-Burgués et al. 2012; Turshatov et al. 2004).

In our present investigation, two calix[4]resorcinarene ionophores which have alkyl chain different substituents, namely: C-dec-9-en-1-ylcalix[4]resorcinarene (I) and C-undecylcalix[4]resorcinarene (II), were utilized to study the interactions and complexation behavior against various heavy metals (Cd, Hg, Pb, and Cu) in producing stable Langmuir monolayers and surface pressure-area isotherms.

2 Experimental

2.1 Ionophores synthesis

The cyclocondensation synthesis, the chemical, and the structural characterization of the ionophores (I) and (II) were described in our previous work (Eddaif et al. 2019d); additionally, the synthetic approaches are presented in Fig. 2.

2.2 Langmuir Compression Isotherms

A rectangular (length: 30 cm, width: 20 cm, depth: 0.5 cm) Langmuir-Blodgett trough (Model 611, NIMA Technology Ltd., Coventry, England) equipped with a Wilhelmy-type surface pressure gauge by means of filter paper (20 mm length) was used to produce all the Langmuir isotherms, the trough was thermostated to 20 °C with a 0.5 °C precision, and was enclosed in a box.

All chemicals were of analytical grade. The Millipore purity deionized water (18.2 MΩ.cm) was used as basic subphase, which later modified with different concentrations (5 ppm, 25 ppm, and 250 ppm) of Pb2+, Cu2+, Hg2+, and Cd2+ ions. Specific amounts of cadmium nitrate (Cd(NO3)2), lead nitrate (Pb(NO3)2), copper nitrate (Cu(NO3)2), and mercury chloride (HgCl2) were thoroughly mixed with pure water to prepare the metal ions different concentration subphases. The resulting solutions were poured inside the trough.

The calix[4]resorcinarene solutions were prepared using chloroform as solvent with a 1mg/ml concentration, and the Langmuir films were produced by dropping uniformly a 20 μl volume of calix[4]resorcinarene solution onto the subphase’s surface using a Hamilton microsyringe, and a time of 10 min was allowed for the solvent evaporation. Then, the barrier was closed to record the surface pressure-area isotherms (the average compression speed was of 100 cm2/min).

3 Results and Discussion

The aim behind the Langmuir isotherm studies was to evaluate the influence of different metal ions on the Langmuir films and on the interactions occurring between those ions and the ionophores. The ionophore surface pressure-area isotherms were acquired at the air/water interface via the surface pressure (Π) recording (expressed in mN/m) against the molecular area variations (Å2). To ensure both the stability and the reproducibility of all Langmuir isotherms, each experiment was repeated at least 3 times; the result comparison showed a good stability, as well as noble reproducibility (Azahari et al. 2014)

3.1 Langmuir Studies: Surface Pressure (Π-A) Isotherms

Tables 1 and 2 summarize all the (Π-A) isotherm data of both ionophore monolayers (I) and (II), whereas Figs. 3a, b, c, d and 4a, b, c, d show the Langmuir isotherm evolution of (I) and (II) using pure water and different (Cd2+, Pb2+, Cu2+, and Hg2+) concentrations as aqueous subphases. The results revealed interesting changes in terms of the limiting area/molecule, as well as selective binding to some metals over others supporting the possibility of using these oligomers as selective chemical sensors. Moreover, further descriptions are stated in the coming paragraphs.

3.1.1 Cadmium Ion Subphase

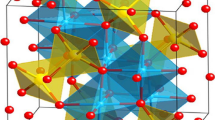

In a general manner, and due to the amphiphilic character of the calix[4]resorcinarene molecules, they can form both well-ordered (stable) and insoluble monolayers at the air/water interface, and consequently, leading to precise Langmuir isotherms. In addition, the calix[4]resorcinarenes ring is assumed to be parallel with the water/air interface’s plane, and mostly, they are stable in a cone conformation; precisely, the alkane or alkene chains (substituents) are in front of the air, whereas the resorcinols hydroxyl groups are tending to form hydrogen bounds with the water molecules (in the aqueous subphase), as mentioned in the literature (Supian et al. 2010).

Figures 3a and 4a show the Langmuir isotherm evolution of both C-dec-9-en-1-ylcalix[4]resorcinarene and C-undecylcalix[4]resorcinarene monolayers using pure water and different Cd2+ concentrations as aqueous subphases. At the compression’s commencement, both ionopohres (I) and (II) undergone a gas-liquid transition for all subphases at ~ 107, ~ 173, ~ 167, and ~ 194 Å2/molecule for (I) and at ~ 135, ~ 160, ~ 230, and ~ 340 Å2/molecule for (II), respectively, for 0, 5, 25, and 250 ppm concentration. A second phase transition is observed for the 25 and 250 ppm concentrations at ~ 105 and ~ 115 Å2/molecule correspondingly for (I) and at about ~ 135 and ~ 170 Å2/molecule for (II). This is attributed to a liquid-quasi solid or a liquid-liquid transition. However, for pure water and 5 ppm Cd2+, the Π value increased without an obvious phase transition reaching the collapse pressure.

The isotherms were not similar considering the phase transitions, which can be explained either by some inter/intra molecular changes, or else by the strong interaction occurring between the monolayers and the ions while increasing their amounts in the subphase. This circumstance was confirmed by the increase of the Alim (limiting area per molecule): obtained by extrapolating the linear part of the isotherm on the ‘x’ axis; the extrapolated Alim values were about ~ 110, ~ 130, ~ 160, and ~ 185 Å2/molecule for (I), and about ~ 105, ~ 150, ~ 220, and ~ 320 Å2/molecule for compound (II), sequentially for pure water, 5, 25, and 250 ppm of Cd2+ ions, therefore demonstrating the incorporation of the cadmium ions into the Langmuir monolayers.

3.1.2 Copper Ion Subphase

By examining Figs. 3b and 4b presenting the monolayers (Π-A) isotherms by means of pure water and different Cu2+ concentrations, it is obvious that upon compression, a gas-liquid transition is observed at about ~ 107, ~ 169, ~ 230, and ~ 330 Å2/molecule (I) and at ~ 135, ~ 190, ~ 385, and ~ 330 Å2/molecule (II), respectively, for 5, 25, and 250 ppm). Furthermore, in the case of (I), a second-phase transition is observable for all copper concentrations (~ 87, ~ 91, and ~ 160 Å2/molecule correspondingly for 5, 25, and 250 ppm), mostly explained by a liquid-liquid transition. Considering the pure water-calix (I) monolayer, only one phase transition was seen while increasing the pressure up to collapse (Ac = 65 Å2/molecule, Πc = 32 mN/m), equally the (II) monolayer went through one principal phase transition for all added copper concentrations (i.e., the pressure increased up to collapse without extra phase transitions).

Evaluating the Alim values, which had an increase with the rise of copper amounts, they were about ~ 110, ~ 150, ~ 200, and ~ 320 Å2/molecule for (I) and ~ 105, ~ 140, ~ 370, and ~ 450 Å2/molecule in case of (II) for 0, 5, 25, and 250 ppm of Cu2+ ions; consecutively, a significant difference in terms of the average area upon addition of various copper amounts is observed, attesting the strong interaction occurring between the Cu2+ ions and the calix[4]resorcinarene monolayers.

3.1.3 Mercury Ion Subphase

The corresponding Langmuir compression isotherms of pure water and various Hg2+ solutions for monolayers of (I) and (II) are displayed in Figs. 3c and 4c. Inspecting both graphs shows that Langmuir films presented two major phase transitions for the mercury containing solutions for (I) while increasing the compression. However, the calix monolayer (II) went through one phase transition only, although there was a little slope variation in the 250 ppm isotherm at about ~ 171 Å2/molecule which is probably attributed to some intermolecular changes rather than a liquid-liquid transition. In both cases, the primary phase transition is a gas-liquid one and could be obtained at ~ 107, ~ 225, ~ 240, and ~ 310 Å2/molecule for (I), also at ~ 135, ~ 230, ~ 300, and ~ 330 Å2/molecule in the case of (II) for 0, 5, 25, and 250 ppm. Afterward, the pressure increased reaching collapse without any other phase transitions in case of (II), as well as the pure water isotherm of (I). The second phase transition shown at ~ 130, ~ 135, and ~ 180 Å2/molecule for 5, 25, and 250 ppm of mercury ions (in case of (I)) is mainly a liquid-liquid transition.

The Alim values were about ~ 110, ~ 220, ~ 240, and ~ 300 Å2/molecule for (I), as well as ~ 105, ~ 220, ~ 290, and ~ 310 Å2/molecule in case of (II) for 0, 5, 25, and 250 ppm of Hg2+ ions, a noteworthy increase is observed, demonstrating the strong interaction occurring between the Hg2+ and the calix[4]resorcinarene monolayers.

3.1.4 Lead Ion Subphase

The analogous Langmuir isotherms formed by the calix[4]resorcinarene-Pb2+ monolayers at air/water interface are presented in Figs. 3d and 4d. After the beginning of compression, the (I) Langmuir monolayers showed two phase transitions for lead solutions (25 and 250 ppm), the first one is seen at ~ 290, and ~ 360 Å2/molecule for 25 and 250 ppm, and the second is observed at ~ 147 and ~ 183 Å2/molecule for 25 and 250 ppm of Pb2+ ions, the first phase transition is mainly attributed to a gas-liquid transition, whereas the second is explained by a liquid-liquid transition. Though the pure water-calix and the 5 ppm isotherms revealed only a gas-liquid, or properly a gas-condensed liquid transition at ~ 107 and 150 Å2/molecule. However, with increasing the Π up to collapse of pure water (Ac = 65 Å2/molecule, Πc = 32 mN/m) and 5 ppm subphase (Ac = 70 Å2/molecule, Πc = 38 mN/m), no additional phase transition was seen. In case of the c-undecylcalix[4]arene monolayer, only one phase transition was shown for all lead solutions at ~ 135, ~ 165, ~ 190, and ~ 315 Å2/molecule for 0, 5, 25, and 250 ppm, it corresponds to a gas-liquid or a gas-condensed liquid transition. Though with increasing the Π up to collapse, no additional phase transition was seen.

It is worth mentioning the observed increase in the limiting areas, therefore indicating the strong inclusion taking place at the Pb-calix monolayer. The Alim values were about ~ 110, ~ 150, ~ 275, and ~ 320 Å2/molecule for (I) and around ~ 105, ~ 160, ~ 170, and ~ 300 Å2/molecule in case of (II) for 0, 5, 25, and 250 ppm of lead ions.

3.2 Ion Discrimination and Selectivity Within (I) and (II) Ionophores

The increase in terms of the average area (limiting area) is a strong indicator of the potential interactions occurring at the water/air interface while studying Langmuir isotherms, in case of using ionophores for complexing, extracting, or else sensing metal ions, the changes happening to the Alim while adjusting the ions amounts in the examined subphases, is a proof of the interaction (complexation) concerning both the ionophores and the metals. However, each molecule has a tendency to one or more metal ions over others; thus, the Fig. 5 is showing the dependence of Alim on the metal ions concentrations, the Alim increased systematically with increasing the ions amounts in the studied subphases for both ionophores, specifically and most rapidly for (I)-Cu2+, (I)-Pb2, (I)-Hg2+, and (II)-Cu2+ indicating that the C-dec-9-en-1-ylcalix[4]resorcinarene is more selective to lead and copper ions over others, whereas the C-undecylcalix[4]resorcinarene is more selective to copper cations over others (Fig. 6).

3.3 Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions Within Ionophores (I) and (II) Monolayers

In this work, we explain the adsorption of various heavy metals ions within the Langmuir monolayers of both ionophores (I) and (II) by means of the Gibbs Eq. (1). Bearing in mind the fact of working in diluted solution conditions, consequently, the heavy metal ion activities are considered equal to their concentrations (aHM~CHM), besides their adsorption factor ΓHM is roughly close to the maximum adsorption of ions ΓmaxHM. Furthermore, the integral of Eq. (1) is presented by the Gibbs–Shishkovsky empirical Eq. (2) (Turshatova et al. 2004).

The collapse pressure differences between the blank and the heavy metals ion subphases (ПcH2O − ПcHM) can be plotted against the ln(CHM). Generally, the slope of this curve is related to the ΓmaxHM as highlighted in Eq. (3). ‘b’ stands for the graphical slope and ‘a’ represents the intercept in Eq. (2), whereas ‘T’ and ‘R’ are signifying the temperature and the universal gas constant in succession. The (ΠcH2O − ΠcHM) variations were calculated using the isotherm data. Afterwards, the ΓmaxHM values were derived from the graphical slope values.

Figure 7 is showing the ΓmaxHM definition plots for ionophores I (a) and II (b) against various HM cations, for all (calix-ion) pairs, the plots were of an approximately linear form.

Hence, an idea about the interaction occurring between each ion and ionophore can be established. In both cases, the collapse pressure was affected by the metals ions present in the subphase. Besides, it is figured out that ionophores (I) and (II) have interactions with all ions, nevertheless with a preference to copper and lead over others at higher concentrations, this fact is translated by positive slope signs, and maximum adsorption values (Table 3).

4 Conclusion

The C-dec-9-en-1-ylcalix[4]resorcinarene (I) and C-undecylcalix[4]resorcinarene (II) formed stable monolayers at the air/water interface; consequently, stable surface pressure-area isotherms were gotten while studying the interactions between those ionophores and various heavy metals, the interactions were strong enough, which supports the prospect of the potential use of these ionophores as sensing platforms. A concentration dependence was seen in both cases; moreover, the ionophore (I) was selective to copper and lead ions, whereas the (II) showed tendency to bind with copper ions. The interactions taking place between the Langmuir monolayers and the heavy metals ions were explained by means of the Gibbs–Shishkovsky adsorption empirical equation.

A further investigation is currently under way, it consists on developing selective piezogravimetric and electrochemical sensing platforms based on the calix[4]resorcinarene derivatives for the selective detection of heavy metal ions.

References

Alam, A. U., Howlader, M. M. R., Hu, N.-X., & Deen, M. J. (2019). Electrochemical sensing of lead in drinking water using β-cyclodextrin-modified MWCNTs. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 296, 126632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2019.126632.

Azahari, N. A., Supian, F. L., Richardson, T. H., & Malik, S. A. (2014). Properties of Calix4-Lead(Pb) Films Using Langmuir-Blodgett (LB) Technique as an Application of Ion Sensor. Advanced Materials Research, 895, 8–11. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.895.8.

Chao, C.-H., Wu, C.-S., Huang, C.-C., Liang, J.-C., Wang, H.-T., Tang, P.-T., et al. (2012). A rapid and portable sensor based on protein-modified gold nanoparticle probes and lateral flow assay for naked eye detection of mercury ion. Microelectronic Engineering, 97, 294–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mee.2012.03.015.

Davis, F., & Stirling, C. J. M. (1996). Calix-4-resorcinarene Monolayers and Multilayers: Formation, Structure, and Differential Adsorption 1. Langmuir, 12(22), 5365–5374. https://doi.org/10.1021/la960543f.

Davis, F., Lucke, A. J., Smith, K. A., & Stirling, C. J. M. (1998). Order and Structure in Langmuir−Blodgett Mono- and Multilayers of Resorcarenes. Langmuir, 14(15), 4180–4185. https://doi.org/10.1021/la980078h.

Eddaif, L., Shaban, A., & Telegdi, J. (2019a). Sensitive detection of heavy metals ions based on the calixarene derivatives-modified piezoelectric resonators: a review. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry, 99(9), 824–853. https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2019.1616708.

Eddaif, L., Shaban, A., & Telegdi, J. (2019b). Application of Calixresorcinarenes as Chemical Sensors. In Proceedings of 1st Coatings and Interfaces Web Conference (p. 6166). Presented at the 1st Coatings and Interfaces Web Conference, Sciforum.net: MDPI. https://doi.org/10.3390/ciwc2019-06166.

Eddaif, L., Shaban, A., Telegdi, J., & Szendro, I. (2019c). A Piezogravimetric Sensor Platform for Sensitive Detection of Lead (II) Ions in Water Based on Calix[4]resorcinarene Macrocycles: Synthesis, Characterization and Detection. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, S1878535219301042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2019.09.002.

Eddaif, L., Trif, L., Telegdi, J., Egyed, O., & Shaban, A. (2019d). Calix[4]resorcinarene macrocycles: Synthesis, thermal behavior and crystalline characterization. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-018-7978-0.

Gong, X., Bi, Y., Zhao, Y., Liu, G., & Teoh, W. Y. (2014). Graphene oxide-based electrochemical sensor: a platform for ultrasensitive detection of heavy metal ions. RSC Advances, 4(47), 24653–24657. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA02247E.

Maeda, H., Tierney, D. L., Mariano, P. S., Banerjee, M., Cho, D. W., & Yoon, U. C. (2008). Lariat-crown ether based fluorescence sensors for heavy metal ions. Tetrahedron, 64(22), 5268–5278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2008.03.031.

Moreira, W. C., Dutton, P. J., & Aroca, R. (1994). Langmuir-Blodgett Monolayers and Vibrational Spectra of Calix[4]Resorcinarene. Langmuir, 10(11), 4148–4152. https://doi.org/10.1021/la00023a039.

Neupane, L. N., Oh, E.-T., Park, H. J., & Lee, K.-H. (2016). Selective and Sensitive Detection of Heavy Metal Ions in 100% Aqueous Solution and Cells with a Fluorescence Chemosensor Based on Peptide Using Aggregation-Induced Emission. Analytical Chemistry, 88(6), 3333–3340. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04892.

Nur Abdul Aziz, S. F., Zawawi, R., & Alang Ahmad, S. A. (2018). An Electrochemical Sensing Platform for the Detection of Lead Ions Based on Dicarboxyl-Calix[4]arene. Electroanalysis, 30(3), 533–542. https://doi.org/10.1002/elan.201700736.

Park, M.-O., Noh, H.-B., Park, D.-S., Yoon, J.-H., & Shim, Y.-B. (2017). Long-life Heavy Metal Ions Sensor Based on Graphene Oxide-anchored Conducting Polymer. Electroanalysis, 29(2), 514–520. https://doi.org/10.1002/elan.201600494.

Pizarro, J., Flores, E., Jimenez, V., Maldonado, T., Saitz, C., Vega, A., et al. (2019). Synthesis and characterization of the first cyrhetrenyl-appended calix[4]arene macrocycle and its application as an electrochemical sensor for the determination of Cu(II) in bivalve mollusks using square wave anodic stripping voltammetry. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 281, 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2018.09.099.

Prochowicz, D., Kornowicz, A., & Lewiński, J. (2017). Interactions of Native Cyclodextrins with Metal Ions and Inorganic Nanoparticles: Fertile Landscape for Chemistry and Materials Science. Chemical Reviews, 117(22), 13461–13501. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00231.

Puccini, M., Guazzelli, L., Tasca, A. L., Mezzetta, A., & Pomelli, C. S. (2018). Development of a Chemosensor for the In Situ Monitoring of Thallium in the Water Network. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 229(7), 239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-018-3883-1.

Ravikumar, Y., Nadarajan, S. P., Lee, C.-S., Jung, S., Bae, D.-H., & Yun, H. (2016). FMN-Based Fluorescent Proteins as Heavy Metal Sensors Against Mercury Ions. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 26(3), 530–539. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1510.10040.

Shahgaldian, P., Pieles, U., & Hegner, M. (2005). Enantioselective Recognition of Phenylalanine by a Chiral Amphiphilic Macrocycle at the Air−Water Interface: A Copper-Mediated Mechanism. Langmuir, 21(14), 6503–6507. https://doi.org/10.1021/la0503101.

Shtepliuk, I., Caffrey, N. M., Iakimov, T., Khranovskyy, V., Abrikosov, I. A., & Yakimova, R. (2017). On the interaction of toxic Heavy Metals (Cd, Hg, Pb) with graphene quantum dots and infinite graphene. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 3934–3934. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04339-8.

Supian, F. L., Richardson, T. H., Deasy, M., Kelleher, F., Ward, J. P., & McKee, V. (2010). Interaction between Langmuir and Langmuir−Blodgett Films of Two Calix[4]arenes with Aqueous Copper and Lithium Ions. Langmuir, 26(13), 10906–10912. https://doi.org/10.1021/la100808r.

Torrent-Burgués, J., Vocanson, F., Pérez-González, J. J., & Errachid, A. (2012). Synthesis, Langmuir and Langmuir–Blodgett films of a calix[7]arene ethyl ester. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 401, 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2012.03.040.

Turshatov, A. A., Melnikovac, N. B., Semchikova, Y. D., Ryzhkinab, I. S., Pashirovab, T. N., Möbiusd, D., & Zaitseve, S. Y. (2004). Interaction of monolayers of calix [ 4 ] resorcinarene derivatives with copper ions in the aqueous subphase. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 240(1-3), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2004.02.031.

Xiang, Y., & Lu, Y. (2014). DNA as Sensors and Imaging Agents for Metal Ions. Inorganic Chemistry, 53(4), 1925–1942. https://doi.org/10.1021/ic4019103.

Xiao, M., Qu, X., Li, L., & Pei, H. (2018). Ultrasensitive Detection of Metal Ions with DNA Nanostructure. In G. Zuccheri (Ed.), DNA Nanotechnology (Vol. 1811, pp. 137–149). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8582-1_9.

Xuan, X., & Park, J. Y. (2017). Miniaturized flexible sensor with reduced graphene oxide/carbon nano tube modified bismuth working electrode for heavy metal detection. In 2017 IEEE 30th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS) (pp. 636–639). Presented at the 2017 IEEE 30th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS). https://doi.org/10.1109/MEMSYS.2017.7863488.

Xuan, X., Hossain, M. F., & Park, J. Y. (2016). A Fully Integrated and Miniaturized Heavy-metal-detection Sensor Based on Micro-patterned Reduced Graphene Oxide. Scientific Reports, 6, 33125. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33125.

Zhang, X.-B., Kong, R.-M., & Lu, Y. (2011). Metal Ion Sensors Based on DNAzymes and Related DNA Molecules. Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry, 4(1), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anchem.111808.073617.

Zhang, C.-Z., Chen, B., Bai, Y., & Xie, J. (2018a). A new functionalized reduced graphene oxide adsorbent for removing heavy metal ions in water via coordination and ion exchange. Separation Science and Technology, 53(18), 2896–2905. https://doi.org/10.1080/01496395.2018.1497655.

Zhang, L., Peng, D., Liang, R.-P., & Qiu, J.-D. (2018b). Graphene-based optical nanosensors for detection of heavy metal ions. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 102, 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2018.02.010.

Zhang, J., Sun, X., & Wu, J. (2019). Heavy Metal Ion Detection Platforms Based on a Glutathione Probe: A Mini Review. Applied Sciences, 9(3), 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9030489.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support from the [BIONANO_GINOP-2.3.2-15-216-00017] project, as well as from the Stipendium Hungaricum Scholarship Program. We thank Dr. Loránd Románszki for his assistance.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Óbuda University (OE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Eddaif, L., Shaban, A. & Telegdi, J. Application of the Langmuir Technique to Study the Response of C-dec-9-en-1-ylcalix[4]resorcinarene and C-undecylcalix[4]resorcinarene Ultra-thin Films' Interactions with Cd2+, Hg2+, Pb2+, and Cu2+ Cations Present in the Subphase. Water Air Soil Pollut 230, 279 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-019-4322-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-019-4322-7