Abstract

Data concerning the benefits and risks of primary PCI in the elderly patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are limited. Thus, the objective of the study was to assess age-dependent differences in the treatment and outcomes of STEMI patients transferred for primary PCI. Data were gathered on 1,650 consecutive STEMI patients from hospital networks in seven countries of Europe from November 2005 to January 2007 (the EUROTRANSFER Registry population). Patients <65, 65 to 74, 75 to 84, and ≥85 years of age comprised 49.3, 27.5, 20.2, and 3 % of the registry population, respectively. Elderly patients were higher risk individuals and have experienced longer delays to reperfusion than their younger counterparts and were more likely to be treated conservatively after coronary angiography. Despite similar frequency of TIMI 3 flow before PCI, elderly patients were less likely to achieve TIMI 3 flow and ST-segment resolution >50 % after PCI, and were more likely to have PCI complications. The rates of death at 30 days, as well as at 1 year were increased with age. In the Cox regression analysis model age was an independent predictor of 30-day mortality. A trend toward higher risk of major bleeding requiring transfusion was observed. Age was an important determinant of treatment strategies selection and clinical outcomes in the group of consecutive STEMI patients transferred for primary PCI. Further efforts should be made to reduce delays and to optimize treatment of STEMI, regardless of patients’ age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Elderly patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are less likely to receive reperfusion therapies, both fibrynolysis and primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [1–3]. Common reasons for excluding older patients from reperfusion therapy are their delayed presentation and atypical symptoms. Also, up to 9 % of elderly patients have absolute contraindication to fibrynolytic therapy [4]. Nowadays, primary PCI is the preferred method of reperfusion for STEMI, also in elderly patients [5]. It has been shown to be more effective than fibrynolysis in reduction of ischemic events in patients ≥75 years old with STEMI with chest pain <6 h [6]. However, primary PCI carries a decreased success rate and an increased procedural risk in older patients when compared with younger ones. Elderly STEMI patients are also at the higher risk of death or other adverse ischemic and non-ischemic events as result of higher prevalence of comorbidities.

Elderly patients with STEMI are often excluded from randomized clinical trials, thus it is hard to generalize expected outcomes from randomized clinical trials to the real life setting. More reliable data on treatment and outcomes of elderly patients with STEMI can be extracted from multicenter registries. The objective of the present study was to assess whether there exist age-dependent differences in the clinical characteristics, treatment strategies and clinical outcomes in patients with STEMI transferred for primary PCI based on data from the European Registry on Patients with ST-Elevation MI Transferred for Mechanical Reperfusion with a Special Focus on Upstream Use of Abciximab (EUROTRANSFER) Registry [7–9].

Methods

The details of the EUROTRANSFER Registry (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00378391) protocol and main results have been previously published [7–9]. In this registry data concerning treatment and outcomes of 1,650 consecutive, transferred STEMI patients in 15 STEMI hospital networks from 7 European countries between November 2005 and January 2007 were collected. For the purpose of this analysis patients were divided into four age groups (<65, 65–74, 75–84 and ≥85 years of age). The study protocol and execution complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Institutional Review Board.

All-cause death, reinfarction and urgent revascularization (PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting) and bleeding complications: puncture site hematoma, intracranial hemorrhage, major bleeding requiring transfusion were evaluated during 30-day follow-up [7]. Additionally 1-year mortality was assessed [8]. Data concerning Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow in the infarct-related artery before and after PCI, ST-segment resolution after PCI, and rate of PCI complications (no-reflow, distal embolization, side branch occlusion, artery perforation) were also provided.

Data were analyzed according to the established standards of descriptive statistics. Results were presented as percentages of patients or medians (inter-quartile range). Differences in dichotomous variables were analyzed using Chi-square test and the Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared by the Kruskal–Wallis test. The difference in death rates between groups during follow-up period was assessed by the Kaplan–Meier method using the log-rank test. In addition, multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to find significant predictors of 30-day death. Risk of 30-day death was expressed as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. All tests were two-tailed and a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Data on 1,650 patients were entered into the EUROTRANSFER Registry database. Patients <65, 65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years of age comprised 49.3, 27.5, 20.2, and 3.0 % of the registry population, respectively. Characteristics of patient population according to age are shown in Table 1. The prevalence of female gender, diabetes mellitus, previous myocardial infarction, previous heart failure symptoms, previous stroke, current smoking and chronic kidney disease, as well as body mass index and diastolic blood pressure changed across age groups.

Data concerning pharmacological and interventional treatment are summarized in Table 2. Elderly patients has experienced longer delays to individual stages of treatment than their younger counterparts (Table 2) and they were less likely to be treated with diagnosis-to-balloon time <90 min (for age <65, 65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 percentage of patients with diagnosis-to-balloon time <90 min was as follows: 40.8, 34.1, 35.1, 34.7 %, p = 0.079). There was no difference in the frequency of unfractionated heparin and abciximab use across age groups, both in pre-cathlab and in the cathlab setting. However, a trend toward less frequent administration of clopidogrel in older patients was observed (Table 2).

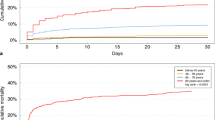

In the coronary angiography prevalence of multivessel disease increased with age. A total of 1,537 patients (93.2 % of study population) underwent immediate PCI. Elderly patients were more likely to be treated conservatively after coronary angiography and were less likely to receive stents, especially drug-eluting stents during immediate PCI (Table 2). TIMI grade 3 flow frequency before PCI was similar among age groups, but elderly patients were less likely to achieve optimal epicardial flow (TIMI grade 3 flow) after PCI, and were more likely to have PCI complications than their younger counterparts (Fig. 1; Table 2). Similarly, rate of ST-segment resolution >50 % after PCI has shown age-dependency.

Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow before and after PCI, and ST-segment resolution >50 % frequency in 1,537 patients undergoing immediate percutaneous coronary intervention stratified by age. PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, STR ST-segment resolution, TIMI Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

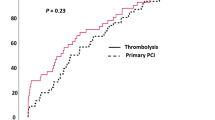

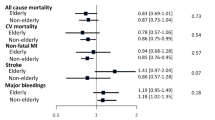

As shown in Fig. 2a, the rates of death, death + reinfarction and all major adverse cardiovascular events at 30 days were increased with age. In contrast, incidences of reinfarction and urgent revascularization at 30 days were independent of age. The Kaplan–Meier curves for survival according to age are shown in Fig. 3. In Cox regression analysis, independent predictors of 30-day death were: age, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke, heart rate on admission, systolic blood pressure on admission, cardiogenic shock (Killip IV) on admission, diagnosis-to-balloon time, stent implantation during PCI, drug-eluting stent implantation during PCI, non-infarct-related artery PCI, left anterior descending artery as infarct-related artery, TIMI grade 3 flow after PCI, ST-segment resolution >50 % after PCI and major bleeding requiring transfusion (Table 3).

As clearly shown in Fig. 2b there were no differences in the occurrence of puncture site hematoma and intracranial hemorrhage (which did not occur in either group) across age groups. A trend toward higher risk of major bleeding requiring transfusion and significantly higher incidence of all bleeding complications in elderly patients (especially ≥85 years of age) were observed.

Discussion

Our study suggests that age is still an important determinant of treatment strategies selection, even in well-organized networks of STEMI treatment. Elderly patients are treated less aggressively in terms of antiplatelet therapy, have experienced longer delays to successful reperfusion, and they are at higher risk of death during follow-up.

In our study, similar to previous studies, and as expected, higher mortality rate was observed in older patients. There are many reasons that contribute to this higher mortality. One of potential explanations of the short- and long-term clinical outcome worsening in elderly STEMI patients is higher prevalence of comorbidities. In line with previous studies, elderly patients were more likely to have diabetes mellitus, previous myocardial infarction, previous heart failure symptoms, previous stroke, and chronic kidney disease [1, 10–14]. Older patients experienced longer time-delays to admission and primary PCI, and presenting more frequently with acute heart failure symptoms. Importantly, ischemia time is a major determinant of survival in patients with STEMI. Another important risk factor for higher mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes is the presence of renal function impairment [15, 16]. Preexisting impairment of renal function, diabetes mellitus and advanced age are also associated with increased risk of contrast induced nephropathy development after coronary angiography and primary PCI, which may led to worsening of long-term prognosis [17, 18]. Elderly patients are also at higher risk of non-cardiac death during follow-up related to cancer or lung diseases. Similarly, to previous reports in our study observed frequency of reinfarction and need of repeated revascularization was comparable across age groups [1, 10].

It is well established that in elderly patients primary PCI success rate is lower, with higher risk of angiographic complications than in younger counterparts [12–14]. In our study, the frequency of optimal epicardial flow (TIMI grade 3 flow) after primary PCI decreases with age. In contrast, in the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) Trial correlation between final epicardial flow after PCI and age was not observed [10]. The complex coronary anatomy observed in elderly patients may be associated with a higher incidence of distal embolization, which is a important determinant of myocardial perfusion after primary PCI, as well as long-term clinical outcome [13, 14, 19]. In addition, De Luca et al. have found a relationship between increased age and impaired myocardial perfusion assessed by myocardial blush grade, and ST-segment resolution. Importantly, age and poor myocardial perfusion were independently associated with 1-year mortality [12]. The higher prevalence of multi-vessel disease and the fear of complications among elderly may account for more frequent selection of initial conservative approach, with postponed PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting. Presence of multi-vessel disease in STEMI patients influences the clinical outcomes of patients treated with primary PCI [20]. Also, as confirmed by our study patients with advanced age are less likely to be treated with drug-eluting stents in STEMI setting [21].

In the analyzed patients population there was a trend toward higher rate of major bleeding requiring transfusion in patients with advanced age [10]. Importantly, major bleeding occurrence is a strong predictor of short- and long-term mortality [22–26]. Also, major bleeding may be associated with higher incidence of ischemic events, for example myocardial infarction, unplanned ischemic revascularization, and stent thrombosis [22]. An increased likelihood of the vascular access site complications (hematomas or aneurysm) in elderly patients is a result of the presence of calcified, fragile and bleeding prone vessels in these patients. In addition, in elderly patients frequently reduced kidney function is leading to overdosing of antithrombotic drugs, and to the increased risk of bleeding. Access site bleeding complications could be decreased by broad usage of radial approach, which was used in <15 % of patients in the EUROTRANSFER registry [27]. Safety and efficacy of transradial catheterization in the elderly is similar to observed in younger patients. Importantly, it may improve the comfort of the patients, especially in the context of the age-related diseases that frequently affect elderly patients [28]. However, advanced age was identified as an independent predictor of selection femoral over radial access by the operator during primary PCI in our registry [27]. Also, a fear of bleeding may limit the use of antiplatelet agents, especially glycoprotein IIb–IIIa inhibitors in patients ≥75 years of age [29]. Importantly, previous studies have shown that patients who present with an acute coronary syndrome and do not receive guideline-recommended therapies, including glycoprotein IIb–IIIa inhibitors experienced higher short- and long-term mortality [30–32].

Limitations of the study

The present study has a number of limitations. First, the study group is relatively small, and the very eldery patient subset (≥85 years of age) comprised only 3 % of the study population. Also, the study focused mainly on 30-day clinical outcomes. Secondly, patients were not screened for contraindications to use of each medication and appropriateness of used dosage was not assessed. It is very likely that in some of patients various therapies were not used due to an important clinical reason. The registry was conducted between November 2005 and January 2007 when new P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel, ticagrelor) were not available. Also, the frequency of bivalirudin monotherapy was rather low, as it was recommended as alternative to unfractionated heparin and glycoprotein IIb–IIIa inhibitors combination recently [5]. Thus, the study did not cover most contemporary pharmacological treatment patterns for STEMI. On the other hand, since year 2007 there was no significant change in the recommendations concerning the application of primary PCI in STEMI setting [5]. Finally, the interpretation of the TIMI flow grade measurements, as well as ST-resolution was limited by the fact that these represent not independent core-lab, but physician’s assessments.

Conclusions

Age was an important determinant of treatment strategies selection and clinical outcomes in the group of consecutive STEMI patients transferred for primary PCI. Further efforts should be made to reduce delays and to optimize treatment of STEMI, regardless of patients’ age.

References

Alexander KP, Newby LK, Armstrong PW, Cannon CP, Gibler WB, Rich MW, Van De Werf F, White HD, Weaver WD, Naylor MD, Gore JM, Krumholz HM, Ohman EM (2007) Acute coronary care in the elderly, part II: ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation 115:2570–2589

Eagle KA, Goodman SG, Avezum A, Budaj A, Sullivan CM, Lopez-Sendon J (2002) Practice variation and missed opportunities for reperfusion in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Lancet 359:373–377

Dudek D, Siudak Z, Kuta M, Dziewierz A, Mielecki W, Rakowski T, Giszterowicz D, Dubiel JS (2006) Management of myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation in district hospitals without catheterisation laboratory: Acute Coronary Syndromes Registry of Malopolska 2002–2003. Kardiol Pol 64:1053–1060

Krumholz HM, Friesinger GC, Cook EF, Lee TH, Rouan GW, Goldman L (1994) Relationship of age with eligibility for thrombolytic therapy and mortality among patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. J Am Geriatr Soc 42:127–131

Van De Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Crea F, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fox K, Huber K, Kastrati A, Rosengren A, Steg PG, Tubaro M, Verheugt F, Weidinger F, Weis M, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Silber S, Aguirre FV, Al-Attar N, Alegria E, Andreotti F, Benzer W, Breithardt O, Danchin N, Di Mario C, Dudek D, Gulba D, Halvorsen S, Kaufmann P, Kornowski R, Lip GY, Rutten F (2008) Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 29:2909–2945

Bueno H, Betriu A, Heras M, Alonso JJ, Cequier A, Garcia EJ, Lopez-Sendon JL, Macaya C, Hernandez-Antolin R (2011) Primary angioplasty vs. fibrinolysis in very old patients with acute myocardial infarction: TRIANA (TRatamiento del Infarto Agudo de miocardio eN Ancianos) randomized trial and pooled analysis with previous studies. Eur Heart J 32:51–60

Dudek D, Siudak Z, Janzon M, Birkemeyer R, Aldama-Lopez G, Lettieri C, Janus B, Wisniewski A, Berti S, Olivari Z, Rakowski T, Partyka L, Goedicke J, Zmudka K (2008) European registry on patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction transferred for mechanical reperfusion with a special focus on early administration of abciximab: EUROTRANSFER Registry. Am Heart J 156:1147–1154

Siudak Z, Rakowski T, Dziewierz A, Janzon M, Birkemeyer R, Stefaniak J, Partyka L, Zmudka K, Dudek D (2010) Early abciximab use in ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention improves long-term outcome. Data from EUROTRANSFER Registry. Kardiol Pol 68:539–543

Rakowski T, Siudak Z, Dziewierz A, Birkemeyer R, Legutko J, Mielecki W, Depukat R, Janzon M, Stefaniak J, Zmudka K, Dubiel JS, Partyka L, Dudek D (2009) Early abciximab administration before transfer for primary percutaneous coronary interventions for ST-elevation myocardial infarction reduces 1-year mortality in patients with high-risk profile. Results from EUROTRANSFER registry. Am Heart J 158:569–575

Guagliumi G, Stone GW, Cox DA, Stuckey T, Tcheng JE, Turco M, Musumeci G, Griffin JJ, Lansky AJ, Mehran R, Grines CL, Garcia E (2004) Outcome in elderly patients undergoing primary coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: results from the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) trial. Circulation 110:1598–1604

Prasad A, Stone GW, Aymong E, Zimetbaum PJ, McLaughlin M, Mehran R, Garcia E, Tcheng JE, Cox DA, Grines CL, Gersh BJ (2004) Impact of ST-segment resolution after primary angioplasty on outcomes after myocardial infarction in elderly patients: an analysis from the CADILLAC trial. Am Heart J 147:669–675

De Luca G, van’t Hof AW, Ottervanger JP, Hoorntje JC, Gosselink AT, Dambrink JH, De Boer MJ, Suryapranata H (2005) Ageing, impaired myocardial perfusion, and mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty. Eur Heart J 26:662–666

DeGeare VS, Stone GW, Grines L, Brodie BR, Cox DA, Garcia E, Wharton TP, Boura JA, O’Neill WW, Grines CL (2000) Angiographic and clinical characteristics associated with increased in-hospital mortality in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous intervention (a pooled analysis of the primary angioplasty in myocardial infarction trials). Am J Cardiol 86:30–34

Batchelor WB, Anstrom KJ, Muhlbaier LH, Grosswald R, Weintraub WS, O’Neill WW, Peterson ED (2000) Contemporary outcome trends in the elderly undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions: results in 7,472 octogenarians. National Cardiovascular Network Collaboration. J Am Coll Cardiol 36:723–730

Yan AT, Yan RT, Tan M, Constance C, Lauzon C, Zaltzman J, Wald R, Fitchett D, Langer A, Goodman SG (2006) Treatment and one-year outcome of patients with renal dysfunction across the broad spectrum of acute coronary syndromes. Can J Cardiol 22:115–120

Dudek D, Chyrchel B, Siudak Z, Depukat R, Chyrchel M, Dziewierz A, Mielecki W, Rakowski T, Rzeszutko L, Dubiel J (2008) Renal insufficiency increases mortality in acute coronary syndromes regardless of TIMI risk score. Kardiol Pol 66:28–34

Brown JR, DeVries JT, Piper WD, Robb JF, Hearne MJ, Ver Lee PM, Kellet MA, Watkins MW, Ryan TJ, Silver MT, Ross CS, MacKenzie TA, O’Connor GT, Malenka DJ (2008) Serious renal dysfunction after percutaneous coronary interventions can be predicted. Am Heart J 155:260–266

McCullough PA, Wolyn R, Rocher LL, Levin RN, O’Neill WW (1997) Acute renal failure after coronary intervention: incidence, risk factors, and relationship to mortality. Am J Med 103:368–375

Henriques JP, Zijlstra F, Ottervanger JP, de Boer MJ, van ‘t Hof AW, Hoorntje JC, Suryapranata H (2002) Incidence and clinical significance of distal embolization during primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 23:1112–1117

Dziewierz A, Siudak Z, Rakowski T, Zasada W, Dubiel JS, Dudek D (2010) Impact of multivessel coronary artery disease and noninfarct-related artery revascularization on outcome of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction transferred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (from the EUROTRANSFER Registry). Am J Cardiol 106:342–347

Dziewierz A, Siudak Z, Rakowski T, Birkemeyer R, Mielecki W, Ranosz P, Dubiel JS, Dudek D (2011) Drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a mortality analysis from the EUROTRANSFER Registry. Clin Res Cardiol 100:139–145

Manoukian SV, Feit F, Mehran R, Voeltz MD, Ebrahimi R, Hamon M, Dangas GD, Lincoff AM, White HD, Moses JW, King SB III, Ohman EM, Stone GW (2007) Impact of major bleeding on 30-day mortality and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: an analysis from the ACUITY Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 49:1362–1368

Eikelboom JW, Mehta SR, Anand SS, Xie C, Fox KA, Yusuf S (2006) Adverse impact of bleeding on prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 114:774–782

Ndrepepa G, Berger PB, Mehilli J, Seyfarth M, Neumann FJ, Schomig A, Kastrati A (2008) Periprocedural bleeding and 1-year outcome after percutaneous coronary interventions: appropriateness of including bleeding as a component of a quadruple end point. J Am Coll Cardiol 51:690–697

Feit F, Voeltz MD, Attubato MJ, Lincoff AM, Chew DP, Bittl JA, Topol EJ, Manoukian SV (2007) Predictors and impact of major hemorrhage on mortality following percutaneous coronary intervention from the REPLACE-2 Trial. Am J Cardiol 100:1364–1369

Rao SV, Jollis JG, Harrington RA, Granger CB, Newby LK, Armstrong PW, Moliterno DJ, Lindblad L, Pieper K, Topol EJ, Stamler JS, Califf RM (2004) Relationship of blood transfusion and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 292:1555–1562

Siudak Z, Zawislak B, Dziewierz A, Rakowski T, Jakala J, Bartus S, Noworolnik B, Zasada W, Dubiel JS, Dudek D (2010) Transradial approach in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with abciximab results in fewer bleeding complications: data from EUROTRANSFER registry. Coron Artery Dis 21:292–297

Molinari G, Nicoletti I, De Benedictis M, Terraneo C, Morando G, Turri M, Anselmi M, Zardini P, Menegatti G, Vassanelli C (2005) Safety and efficacy of the percutaneous radial artery approach for coronary angiography and angioplasty in the elderly. J Invasive Cardiol 17:651–654

Schwarz AK, Zahn R, Hochadel M, Kerber S, Hauptmann KE, Glunz HG, Mudra H, Darius H, Zeymer U (2011) Age-related differences in antithrombotic therapy, success rate and in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the quality control registry of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausarzte (ALKK). Clin Res Cardiol 100:773–780

Alexander KP, Roe MT, Chen AY, Lytle BL, Pollack CV Jr, Foody JM, Boden WE, Smith SC Jr, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Peterson ED (2005) Evolution in cardiovascular care for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE National Quality Improvement Initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol 46:1479–1487

Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA (2007) Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 297:177–186

Dziewierz A, Siudak Z, Rakowski T, Mielecki W, Giszterowicz D, Dubiel JS, Dudek D (2007) More aggressive pharmacological treatment may improve clinical outcome in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes treated conservatively. Coron Artery Dis 18:299–303

Acknowledgements

EUROTRANSFER Registry was an academic research project, which was supported by a research grant from Eli Lilly and Company, Critical Care Europe, Geneva, Switzerland.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dziewierz, A., Siudak, Z., Rakowski, T. et al. Age-related differences in treatment strategies and clinical outcomes in unselected cohort of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction transferred for primary angioplasty. J Thromb Thrombolysis 34, 214–221 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-012-0713-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-012-0713-y