Abstract

If someone claims that individuals behave as if they violate the independence axiom (IA) when making decisions over simple lotteries, it is invariably on the basis of experiments and theories that must assume the IA through the use of the random lottery incentive mechanism (RLIM). We refer to someone who holds this view as a Bipolar Behaviorist, exhibiting pessimism about the axiom when it comes to characterizing how individuals directly evaluate two lotteries in a binary choice task, but optimism about the axiom when it comes to characterizing how individuals evaluate multiple lotteries that make up the incentive structure for a multiple-task experiment. We reject the hypothesis about subject behavior underlying this stance: we find that preferences estimated with a model that assumes violations of the IA are significantly affected when one elicits choices with procedures that require the independence assumption, as compared to choices elicited with procedures that do not require the assumption. The upshot is that one cannot consistently estimate popular models that relax the IA using data from experiments that assume the validity of the RLIM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Cubitt et al. (1998, p. 119) explain the logic of the indirect tests: “Our strategy is to take as the maintained hypothesis that the random lottery design is unbiased. We test this hypothesis in situations in which we have a priori expectations that individuals’ preferences violate the IA in ways which, if the contamination hypothesis were true, would induce observable biases.” All studies using indirect tests of this kind, which of course rest on premisses that might be false, also report direct tests.

Our use of the term “bipolar” is to convey diametrically opposed views, and not to imply mental illness. Of course, one could instead view the term as a colorful metaphor, with a little bite to it. Indeed, we openly admit to such bipolar attitudes at times in our own research.

Conlisk (1989, p. 406) has a very clear statement of the problem, and the need for the 1-in-1 protocol. He uses the 1-in-1 protocol in his test of the Allais Paradox with real monetary consequences, incidentally finding no evidence whatsoever for the alleged anomaly, but does not test it behaviorally against the 1-in-K protocol. Starmer and Sugden (1991) were the first to undertake that behavioral comparison.

In those experiments the elicitation procedure for the certainty-equivalents of simple lotteries was, itself, a compound lottery. Hence the validity of the incentives for this design required both Compound IA and ROCL, hence Mixture IA. Holt (1986) and Karni and Safra (1987) showed that if Compound IA was violated, but ROCL and transitivity was assumed, one might still observe choices that suggest “preference reversals.” Segal (1988) showed that if ROCL was violated, but Compound IA and transitivity was assumed, that one might also still observe choices that suggest “preference reversals.”

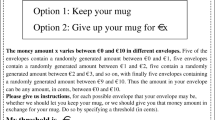

Given the ubiquity of the RLIM in the laboratory, surely past studies have definitively verified the empirical validity of the isolation effect? Unfortunately, this is not the case. A few studies have focused on this issue, but conclusions differ and the verdict is still out on whether use of the RLIM biases behavior. All of these studies consider direct and indirect violations of the IA underlying the RLIM. Direct violations come from comparisons of choices 1-in-1 with 1-in-K payment procedures in the experiments, exactly as in our design, and indirect violations come from comparisons of choices that have a “trip-wire” prediction from EUT (and any decision-making model that assumes IA). These indirect violations are variants of the Allais phenomena known as “Common Ratio” effects and “Common Consequence” effects. Focusing just on the direct tests, comparable to our design, we find mixed results in the previous literature. Starmer and Sugden (1991) find the same pattern of choices in one 1-in-1 versus 1-in-2 comparison, and a different pattern in another comparison. Their design only had two pairs of choices, so \(K=2\); indeed, all of the previous studies had a small K. Beattie and Loomes (1997) used \(K=4\), and found no difference between the 1-in-1 and 1-in-4 choices over three pairs of binary lottery choices. They did find a difference between the 1-in-1 and 1-in-4 choices over the single “multiple lottery choice” task, patterned after Binswanger (1980). Online Appendix C contains a more complete summary of the previous literature.

In general we focus throughout on lotteries defined over objective probabilities. Remarkably, Bade (2011) shows that the 1-in-K payment protocol does not immediately generate inferential problems for some models of choices over lotteries defined over ambiguous acts, such as the maxmin expected utility model. However, for the popular “smooth” models of ambiguity aversion, the 1-in-K protocol does generate problems if the smooth model is compatible with the notion of stochastic independence.

The original battery includes repetition of some choices, to help identify the “error rate” and hence the behavioral error parameter, defined later. In addition, the original battery was designed to be administered in its entirety to every subject. We decided a priori that 30 choice tasks was the maximum that our subject pool could focus on in any one session, given the need in some sessions for there to be later tasks.

To be precise, when there was an extra task subjects were told that “All payoffs are in cash, and are in addition to the $7.50 show–up fee that you receive just for being here, as well as any other earnings in other tasks.” In all other cases subjects were told that “All payoffs are in cash, and are in addition to the $7.50 show–up fee that you receive just for being here. The only other task today is for you to answer some demographic questions. Your answers to those questions will not affect your payoffs.”

A video camera captured images at the front table and broadcasted the images to displays throughout the lab. In addition to a large projection screen in the front, there are three wide-screen TV displays spread throughout the lab so that every cubicle has a clear view of the images.

An additional subtlety arises if one posits random coefficients. In this case, the estimates for any structural parameter, such as the behavioral error parameter, will have a distribution that characterizes the population. If that population distribution is assumed to be Gaussian, as is often the case, there will be a point estimate and standard error estimate of the population mean, and a point estimate and standard error estimate of the population standard deviation. With a consistent estimator, increased sample sizes imply that both standard error estimates will decrease, but the point estimate of the population standard deviation need not.

Our results suggest a research strategy to properly evaluate the validity of EUT in an efficient manner. Examine the catalog of anomalies that arise in choice tasks over simple lotteries using a 1-in-K payment protocol, for some large K, and then for those anomalies that survive, drill down with the more expensive 1-in-1 protocol. This strategy does run the risk that there could be “offsetting violations” of EUT in the 1-in-K payment protocol, but that is a tradeoff that many scholars would, we believe, be willing to take in the interests of efficient use of an experimental budget. And the alternative to the tradeoff is simple enough: replicate every anomaly using the 1-in-1 payment protocol, as in the non-hypothetical experiments of Conlisk (1989).

Binmore (2007, p. 6ff.) has long made the point that we ought to recognize that the artefactual nature of the usual laboratory tasks, and indeed some tasks in the field, means that we should allow subjects to learn how to behave in that environment before drawing unconditional conclusions. Although his immediate arguments are about the study of strategic behavior in games, they are general. These arguments also suggest that a 1-in-1 payment protocol might not be the Gold Standard if one is interested in external validity, whatever its role in terms of internal validity.

One could mitigate the issue by providing subjects with lots of experience in one session, and then invite them back for further experiments, either 1-in-1 or 1-in-30, arguing on a priori grounds that any differences in behavior then should reflect longer-run, steady-state behavior for this task. We are sympathetic to this view, and indeed it was implicit in the early days of experimental economics where “experience” meant that a subject has participated in some task and then had time to “sleep on it” before the next session. The hypothesis implied here is that the differences we find would diminish if subjects were given “enough” experience, which is of course testable if someone can ever define what “enough” means.

In fact, one of the earliest statements of this Recursive RDU model by Segal (1988) was in the context of offering an explanation of preference reversals behavior being logically consistent with the validity of the Compound IA. It is therefore theoretically possible that the RLIM procedure is suspect but the Compound IA is valid, so that one does not have to take a bipolar stance about the Compound IA after all. On the other hand, evidence that payment protocols do affect behavior is then evidence against the Mixture IA, so the hypothesis to be tested to support the stance of the Bipolar Behaviorist is then with respect to ROCL.

References

Andersen, S., Harrison, G. W., Hole, A. R., Lau, M. I., & Rutström, E. E. (2012). Non-linear mixed logit. Theory and Decision, 73, 77–96.

Bade, S. (2011). Independent randomization devices and the elicitation of ambiguity averse preferences. Working Paper, Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, Bonn.

Beattie, J., & Loomes, G. (1997). The impact of incentives upon risky choice experiments. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 14, 149–162.

Binmore, K. (2007). Does game theory work? The bargaining challenge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Binswanger, H. P. (1980). Attitudes toward risk: Experimental measurement in rural India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 62, 395–407.

Camerer, C. F. (1989). An experimental test of several generalized utility theories. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 2, 61–104.

Camerer, C. F. (1992). Recent tests of generalizations of expected utility theory. In W. Edwards (Ed.), Utility theories: Measurements and applications. Boston, MA: Kluwer.

Camerer, C., & Ho, T.-H. (1994). Violations of the betweenness axiom and nonlinearity in probability. Journal of Risk & Uncertainty, 8, 167–196.

Conlisk, J. (1989). Three variants on the Allais example. American Economic Review, 79(3), 392–407.

Cubitt, R. P., Starmer, C., & Sugden, R. (1998). On the validity of the random lottery incentive system. Experimental Economics, 1(2), 115–131.

Cox, J. C. Sadiraj, V. & Schmidt, U. (2011). Paradoxes and mechanisms for choice under risk. Working Paper 2011–12, Center for the Economic Analysis of Risk, Robinson College of Business, Georgia State University, 2011 (revised 2014); forthcoming, Experimental Economics.

Grether, D. M., & Plott, C. R. (1979). Economic theory of choice and the preference reversal phenomenon. American Economic Review, 69(4), 623–638.

Harless, D. W., & Camerer, C. F. (1994). The predictive utility of generalized expected utility theories. Econometrica, 62(6), 1251–1289.

Harrison, G. W., & Rutström, E. E. (2008). Risk aversion in the laboratory. In J. C. Cox & G. W. Harrison (Eds.), Risk aversion in experiments (Vol. 12). Bingley: Emerald, Research in Experimental Economics.

Harrison, G. W., & Rutström, E. E. (2009). Expected utility and prospect theory: One wedding and a decent funeral. Experimental Economics, 12(2), 133–158.

Hey, J. D., & Orme, C. (1994). Investigating generalizations of expected utility theory using experimental data. Econometrica, 62(6), 1291–1326.

Holt, C. A. (1986). Preference reversals and the independence axiom. American Economic Review, 76, 508–514.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655.

Karni, E., & Safra, Z. (1987). Preference reversals and the observability of preferences by experimental methods. Econometrica, 55, 675–685.

Prelec, D. (1998). The probability weighting function. Econometrica, 66, 497–527.

Quiggin, J. (1982). A theory of anticipated utility. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 3(4), 323–343.

Saha, A. (1993). Expo-power utility: A flexible form for absolute and relative risk aversion. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 75(4), 905–913.

Samuelson, P. A. (1952). Probability, utility, and the independence axiom. Econometrica, 20, 670–678.

Segal, U. (1987). The Ellsberg paradox and risk aversion: An anticipated utility approach. International Economic Review, 28, 145–154.

Segal, U. (1988). Does the preference reversal phenomenon necessarily contradict the independence axiom? American Economic Review, 78(1), 233–236.

Segal, U. (1990). Two-stage lotteries without the reduction axiom. Econometrica, 58(2), 349–377.

Segal, U. (1992). The independence axiom versus the reduction axiom: Must we have both? In W. Edwards (Ed.), Utility theories: measurements and applications. Boston, MA: Kluwer.

Starmer, C. (1992). Testing new theories of choice under uncertainty using the common consequence effect. Review of Economic Studies, 59, 813–830.

Starmer, C. (2000). Developments in non-expected utility theory: The hunt for a descriptive theory of choice under risk. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(2), 332–382.

Starmer, C., & Sugden, R. (1991). Does the random-lottery incentive system elicit true preferences? An experimental investigation. American Economic Review, 81, 971–978.

Wakker, P. P., Erev, I., & Weber, E. U. (1994). Comonotonic independence: The critical test between classical and rank-dependent utility theories. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 9, 195–230.

Wilcox, N. T. (1993). Lottery choice: Incentives, complexity, and decision time. Economic Journal, 103, 1397–1417.

Wilcox, N. T. (2008). Stochastic models for binary discrete choice under risk: A critical primer and econometric comparison. In J. Cox & G. W. Harrison (Eds.), Risk aversion in experiments (Vol. 12). Bingley: Emerald, Research in Experimental Economics.

Wilcox, N. T. ( 2010). A comparison of three probabilistic models of binary discrete choice under risk. Working Paper, Economic Science Institute, Chapman University.

Wilcox, N. T. (2011). Stochastically more risk averse: A contextual theory of stochastic discrete choice under risk. Journal of Econometrics, 162(1), 89–104.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jim Cox, Jimmy Martínez, John Quiggin, Elisabet Rutström, Vjollca Sadiraj, Ulrich Schmidt, Uzi Segal, and Nathaniel Wilcox for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harrison, G.W., Swarthout, J.T. Experimental payment protocols and the Bipolar Behaviorist. Theory Decis 77, 423–438 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-014-9447-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-014-9447-y