Abstract

Economic agents often consider the consequences of their actions not only for themselves, but for others as well. In these scenarios, either the magnitude of the cost to the agent, or of the gain to beneficiaries, are often uncertain. Until recently, experimental economic studies of altruistic preferences have neglected this consideration, treating both the costs and benefits of other-regarding actions as deterministic. This paper joins a recent body of literature in explicitly incorporating uncertainty into other-regarding decisions. Using Dictator Games and a 2 × 2 experimental design, we analyze giving in situations where both Dictators’ and Receivers’ payoffs can take the form of either lotteries or cash. We find Dictators much more willing to sacrifice their own cash, than to decrease their own chances of wining a lottery, to benefit Receivers. Receivers’ asset type, on the other hand, has little effect on Dictators’ giving. Income effects are also significantly stronger when Dictators’ assets are lotteries. These results can be explained, albeit only partially, by Dictators who are risk-averse over their own wealth, but not over Receivers’ wealth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Engel [2011] or Chapter 2 of Camerer [2003] for a survey of experimental results.

Andreoni and Miller [2002], Fisman et al [2007] and Jakiela [2013] also test for price-sensitivity in deterministic Dictator Games.

Note that the two panels of Figure 1, while representing different treatments (CC and CL), offer the same expected earnings to both Dictator and Receiver for each of the 11 options.

Options j=2, …, 10 yield

for the Dictator, and

for the Dictator, and  for the Receiver, making higher numbers correspond to more generous choices by the Dictator.

for the Receiver, making higher numbers correspond to more generous choices by the Dictator.A drawback of focusing on the Fraction of the Dictator’s Surplus Sacrificed is that it overstates the generosity of Dictators who give up large fractions of small surpluses.

To maintain cross-treatment comparability, all subjects were informed of the exact Option chosen by the Dictator. Recall that there is no one-to-one relationship between earnings and Dictator decisions, with the exception of Treatment CC.

If u DD is more concave than u DR , u D (π R , π D ) will increase discretely as π R surpasses π D .

See Appendix A for second-derivatives of the expected utility functions with respect to Eπ R for each Treatment, which are negative over

.

.See Appendix B for a discussion of the evolution of the giving measures over time.

This is low compared to other Dictator Games in the existing literature, including the 28.3 percent “give rate” reported in Engel’s [2011] Meta-Study. There are reasons unrelated to our research question why this may be the case. First, our Receivers are better off, relative to Dictators, than in classic Dictator Games. Second, Dictator choices are constrained, and in most cases Dictators do not have the option of giving 100 percent of their allocation so the mean of our results are not drawn as far upwards by the most generous subjects. Note that the average fraction of Dictator’s surplus sacrificed, 28.9 percent, is quite close to Engel’s figure.

For the six measures listed, the nonparametric Somers’ D test, with standard error clustered at the subject level, yields P<0.001.

As discussed in the section “Theoretical background”, concave u dd predicts more interior solutions, so if Dictators typically gave more than they keep, they would give less when their assets are lotteries.

Somers’ D test with clustered errors yields P values of 0.864, 0.883, 0.983, and 0.950 for the four statistics listed in Table 3, in the order listed.

Recall from Section “Theoretical background” that risk-averse u DD makes a Dictator choose

more frequently.

more frequently.In the interval regression, Option 1 is interpreted as revealing a preference to give in the range of 0 to 5 percent of the Dictator’s surplus, Option 2 to give between 5 and 15 percent, and so on.

As regressions in Columns (1) and (2) use Receiver’s total expected wealth as the dependent variable, increasing

by $1 increases Eπ

R

by less than $1, suggesting that they are given less by the Dictator.

by $1 increases Eπ

R

by less than $1, suggesting that they are given less by the Dictator.Unlike classic Dictator Games, our Dictators generally do not have the option to sacrifice all of their earnings.

See Table B1 in Appendix B, as well as the coefficient on “Dict. Lottery” in Table 4.

As Dictators typically give a small amount of their surplus, their decisions reveal more about their preferences over their own earnings than about their preferences over Receivers’ earnings.

References

Andreoni, James, and John Miller . 2002. Giving According to GARP: An Experimental Test of the Consistency of Preferences for Altruism. Econometrica, 70 (2): 737–753.

Andreoni, James, and Lise Vesterlund . 2001. Which is the Fair Sex? Gender Differences in Altruism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116 (1): 293–312.

Bolton, Gary E., and Axel Ockenfels . 2000. ERC: A Theory of Equity, Reciprocity, and Competition. American Economic Review, 90 (1): 166–193.

Bolton, Gary E, Jordi Brandts, and Axel Ockenfels . 2005. Fair Procedures: Evidence from Games Involving Lotteries. Economic Journal, 115 (506): 1054–1076.

Brock, J. Michelle, Andreas Lange, and Erkut Y. Ozbay . 2013. Dictating the Risk: Experimental Evidence on Giving in Risky Environments. American Economic Review, 103 (1): 415–437.

Burnham, Terence C. 2003. Engineering Altruism: A Theoretical and Experimental Investigation of Anonymity and Gift Giving. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 50 (1): 133–144.

Camerer, Colin F. 2003. Behavioral Game Theory. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cappelen, Alexander W., James Konow, Erik Ø. Sørensen, and Bertil Tungodden . 2013. Just Luck: An Experimental Study of Risk-Taking and Fairness. American Economic Review, 103 (4): 1398–1413.

Chakravarty, Sujoy, Glenn W. Harrison, Ernan E. Haruvy, and E. Elisabet Rutström . 2011. Are You Risk Averse over Other People’s Money? Southern Economic Journal, 77 (4): 901–913.

Charness, Gary, and Matthew Rabin . 2002. Understanding Social Preferences With Simple Tests. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117 (3): 817–869.

Charness, Gary, and Uri Gneezy . 2008. What’s in a Name? Anonymity and Social Distance in Dictator and Ultimatum Games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68 (1): 29–35.

Dana, Jason, Roberto Weber, and Jason Kuang . 2007. Exploiting Moral Wiggle Room: Experiments Demonstrating an Illusory Preference for Fairness. Economic Theory, 33 (1): 67–80.

Eckel, Catherine C., and Philip J. Grossman . 1996. Altruism in Anonymous Dictator Games. Games and Economic Behavior, 16 (2): 181–191.

Eckel, Catherine C., and Philip J. Grossman . 1998. Are Women Less Selfish Than Men? Evidence from Dictator Experiments. Economic Journal, 108 (448): 726–735.

Engel, Christoph . 2011. Dictator Games: A Meta Study. Experimental Economics, 14 (4): 583–610.

Fehr, Ernst, and Klaus Schmidt . 1999. A Theory of Fairness, Competition, and Cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114 (3): 817–868.

Fischbacher, Urs . 2007. z-Tree: Zurich Toolbox for Ready-made Economic Experiments. Experimental Economics, 10 (2): 171–178.

Fisman, Raymond, Shachar Kariv, and Daniel Markovits . 2007. Individual Preferences for Giving. American Economic Review, 97 (5): 1858–1876.

Fudenberg, Drew, and David Knudsen Levine . 2012. Fairness, Risk Preferences and Independence: Impossibility Theorems. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 81 (2): 606–612.

Greiner, Ben . 2003. An Online Recruitment System for Economic Experiments. Forschung und wissenschaftliches Rechnen, 63: 79–93.

Jakiela, Pamela . 2013. Equity vs. Efficiency vs. Self-Interest: On the Use of Dictator Games to Measure Distributional Preferences. Experimental Economics, 16 (2): 208–221.

Kahneman, Daniel, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler . 1986. Fairness and the Assumptions of Economics. The Journal of Business, 59 (4): S285–S300.

Krawczyk, Michal W. 2011. A Model of Procedural and Distributive Fairness. Theory and Decision, 70 (1): 111–128.

Krawczyk, Michal W., and Fabrice Le Lec . 2010. Give Me a Chance! An Experiment in Social Decision Under Risk. Experimental Economics, 13 (4): 500–511.

Oxoby, Robert J., and John Spraggon . 2008. Mine and Yours: Property Rights in Dictator Games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 65 (3–4): 703–713.

Ponti, Giovani, Ismael Rodriguez-Lara, and Daniela Di Cagno . 2013. Doing it Under the Influence of Others: Experimental Evidence on Social Time Preferences. Working Paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix A

Addendum to theory

Utility function second derivatives

Appendix B

Addendum to results

Altruism regressions by dictator surplus and wealth

Table B1 presents a series of Tobit regressions, each using the Receiver’s Yield,  , as the dependent measure. The top and bottom panels contain the compressed results of 10 regressions each, with each panel separating observations by a different dimension. The top panel groups observations by

, as the dependent measure. The top and bottom panels contain the compressed results of 10 regressions each, with each panel separating observations by a different dimension. The top panel groups observations by  , so regressions include decisions in which Dictators had the same total surplus to give. The regressions of the bottom panel split the observations on a different dimension,

, so regressions include decisions in which Dictators had the same total surplus to give. The regressions of the bottom panel split the observations on a different dimension,  . Thus, regressions in the bottom panel allow us to compare across-treatment results for different Dictator wealth levels individually. The table will further aid the possibility that risk preferences explain our main result, that Dictators are more generous when their assets are lotteries.

. Thus, regressions in the bottom panel allow us to compare across-treatment results for different Dictator wealth levels individually. The table will further aid the possibility that risk preferences explain our main result, that Dictators are more generous when their assets are lotteries.

The regularities observed in Table 4 are reproduced in nearly all of the regressions in both panels of Table B1. This suggests not only that the results are robust, but that they are remarkably consistent across the amount of available surplus (top panel) and wealth levels (bottom panel). The fact that the coefficient on “Dict. Lottery” is uniformly negative, and nearly uniformly significant, rules out risk preferences as the sole explanation for our results.

Giving over time

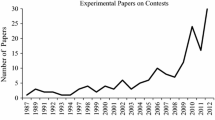

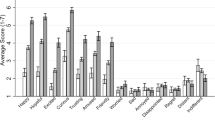

As subjects in our design make 50 similar decisions in a short period of time, the evolution of giving behavior over the course of the session warrants discussion. Figure B1 displays the means of each of the giving measures discussed, partitioned into 10-period bins.

As seen in Figure B1, giving behavior evolves a bit after the beginning of the session, then converges to a fairly stable level. The main finding of this paper, that Dictators are less generous when their asset is a lottery (Treatments LC and LL), is nonetheless still verified in the first 10 rounds (P=0.015 for Eπ R , P<0.001 for the other three measures, according to the Somers’ D test.) The insignificant effect of the Receiver’s asset type is also observed in the first 10 rounds (P=0.357, P=0.212, P=0.328, and P=0.354, Somers’ D, for the four measures in the order listed).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Owens, D. Lotteries in Dictator Games: An Experimental Study. Eastern Econ J 42, 399–414 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2014.61

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2014.61

for the Dictator, and

for the Dictator, and  for the Receiver, making higher numbers correspond to more generous choices by the Dictator.

for the Receiver, making higher numbers correspond to more generous choices by the Dictator. .

. more frequently.

more frequently. by $1 increases Eπ

R

by less than $1, suggesting that they are given less by the Dictator.

by $1 increases Eπ

R

by less than $1, suggesting that they are given less by the Dictator.

; (c)

; (c)  ; (d)

; (d)  .

.