Abstract

Traditional epistemologists assumed that the most important doxastic norms were rational requirements on belief. This orthodoxy has recently been challenged by the work of revolutionary epistemologists on the rational requirements on credences. Revolutionary epistemology takes it that such contemporary work is important precisely because traditional epistemologists are mistaken—credal norms are more fundamental than, and determinative of, belief norms. To make sense of their innovative project, many revolutionary epistemologists have also adopted another commitment, that norms on credences are governed by a fundamental accuracy norm. Unfortunately for the revolutionary epistemologist, it has been difficult to define a measure of accuracy while maintaining that credal norms are more basic than belief norms. In this paper, I criticize one such proposal for measuring accuracy, that the accuracy of our credences should be assessed in terms of what we know, arguing that this picture ultimately cannot vindicate the revolutionary approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Epistemologists traditionally took it that beliefs were the most important doxastic attitude to which rational norms applied. For much of epistemology’s history, this was because belief norms were the only ones which were explicitly theorized. Thus, consciously or unconsciously, traditional epistemology held that epistemic norms were at their most fundamental norms on belief. Recently, however, attention has shifted to the rationality of credence, with many claiming that rational credences are more fundamental than rational beliefs. These revolutionary epistemologists thus advocate a turn to Credence First accounts of the rationality of belief:

Credence First The rational norms for belief completely or partially depend on and are determined by the rational norms for credence, and thus the norms for credence are more fundamental. David Christensen exemplifies this view when he expresses doubt that belief is “subject to interesting rational constraints beyond those affecting degrees of confidence.”Footnote 1 On this view, the foundational theoretical work is discovering the norms that govern the rationality of credence, revealing one of the central projects of traditional epistemology, discovering the norms on rational belief apart from norms on credences, to be sterile.

Despite the advent of revolutionary epistemology, in keeping with traditional epistemology, many instead advocate the Belief First program:

Belief First Norms on belief are more fundamental than the norms governing credence. Credal norms in fact depend on belief norms, and thus the recent spate of interest in norms on credences does not threaten the relevance of research programs and theories concerning the rationality of belief.Footnote 2

Credence First and Belief First do not, however, exhaust the logical space, for it could be that there is not an interesting dependence relationship in either direction between belief norms and credal norms. Thus, even more recently than the advent of revolutionary epistemology, there have been those who have advocated for this very sort of Independence:

Independence While there are norms on both beliefs and credences, these norms do not have any dependence relationships. Lara Buchak illustrates Independence, claiming, “It turns out we need belief, and its accompanying epistemology, precisely because there is a domain in which our norms involving beliefs are sensitive to the kinds of evidential connections that belief tracks but credence does not.”Footnote 3 On this view, investigation into the norms governing belief and credence can carry on separately, perhaps with some interesting comparative insights, but nevertheless as distinct endeavors.

My position is that the accuracy approach adopted by many advocates of Credence First is still yet to make good on its claim to upend traditional theorizing about belief. This is because, on one of the most prominent ways of making sense of credal accuracy, the rationality of credences does not end up being more fundamental than the rationality of belief.Footnote 4 In Sect. 2, I introduce the accuracy approach to credal norms, showing in Sect. 3 that there is still an open question concerning which worlds should be used to measure credal accuracy. According to a popular proposal by Leitgeb and Pettigrew (2010), the rationality of credences is determined by the worlds that are epistemically possible for an epistemic agent—the worlds that are not ruled out by what an agent knows. I argue, however, in Sects. 4 and 5, that an account that is based in knowledge does not result in a Credence First account. If it really is the case, as the revolutionary epistemologist would have us believe, that discussions of justified belief are besides the point at best and a waste of time at worst, then leaving behind the defunct research program of traditional epistemology is a priority for making progress on what rationality requires. The argument advanced in this paper shows that such a dismissal of the traditional approach is too quick, and this because it is not yet clear how to determine the rationality of credences while also taking credal norms to be the most fundamental epistemic norms.

Before we begin, it should be noted that it is possible to understand the fundamentality claims of the preceding positions in two senses. One can think that, metaphysically speaking, beliefs just are credences of a certain sort, or vice versa, that credences are a certain kind of belief, and thus that beliefs or credences are descriptively more fundamental. It is also possible to hold a separate thesis, that the norms on belief are dependent on credal norms, or the reverse, that the norms that apply to credences are dependent on the norms that apply to beliefs. Some answers to these two questions fit together rather effortlessly—being a metaphysical reductionist is straightforwardly paired with a form of normative reduction, and motivation for Independence follows naturally from denying a metaphysical reduction of either beliefs to credences or credences to beliefs or vice versa. Crucially, my argument does not depend on any claim of metaphysical reduction of credences to to beliefs or vice versa. Instead, my argument proceeds by taking a proposal concerning the rationality of credences at face value, arguing that this cannot be filled in consistent with the Credence First account. For this reason, my primary argument does not require taking a position on the metaphysical relationship between beliefs and credences.

2 Accuracy as fundamental

2.1 Understanding accuracy

Revolutionary epistemologists argue that credal norms can be derived from a distinctively epistemic form of value—closeness to truth. Credences should be evaluated in terms of how well they satisfy the central aim of getting close to the truth—in a slogan, rational credences should maximize accuracy:

Jim Joyce—An epistemically rational agent...must strive to hold a system of partial beliefs that, in her best judgment, is likely to have an overall gradational accuracy at least as high as that of any alternative system she might adoptFootnote 5

Hannes Leitgeb and Richard Pettigrew—An epistemic agent ought to approximate the truth. In other words, she ought to minimize her inaccuracyFootnote 6

Miriam Schoenfield—The rational epistemic plan is the one that a rational agent would choose, a priori, if she were aiming to maximize the expected accuracy of the credences the agent would adoptFootnote 7

There are a couple discrepancies in these proposals. To begin with, Leitgeb and Pettigrew characterize rationality as requiring that an agent minimize the inaccuracy of their credences instead of maximizing accuracy. Rather than a disagreement, this is only a difference in description. An agent whose situation rationalizes a .8 credence in p both maximizes their accuracy regarding p and minimizes their inaccuracy regarding p when they assign a .8 credence to p.Footnote 8 A more notable difference in these proposals, and a point worth emphasizing, is the distinctive way each author characterizes expected accuracy. Just like the rationality of action is not determined by the actual utility produced by courses of action but rather the expected utility of those actions, the rationality of credences is determined not by their actual accuracy but their expected accuracy. Schoenfield talks explicitly of expected accuracy, Joyce says the relevant credal accuracy is the accuracy of an agent’s credences in her best judgment, and Leitgeb and Pettigrew clarify that, in minimizing inaccuracy, an agent ought to minimize inaccuracy by their own lights from an internalist point of view.Footnote 9 Thus, rational agents are not required to maximize accuracy relative to the actual world (if this were the case, they would be required to have a credence of one in all truths and zero in all falsehoods) but instead ought to maximize accuracy from their unique perspective.

2.2 Measuring accuracy

The next task is to get clear on precisely how to measure expected accuracy. To begin with, we can determine the accuracy of an agent’s credences for a particular world. If we assign the value of the proposition p at the actual world to either one or zero, the inaccuracy of the agent’s credence can be determined by measuring the distance between the value of p and the agent’s credence that p. Supposing that p is false in the actual world, where cr(p) = x, we get the inaccuracy of cr(p) by measuring the distance from x to zero as in (1):

Given that, from the agent’s point of view, the possible worlds under consideration include more than just the actual world, total expected accuracy regarding p is given by summing over the accuracy of the agent’s credence in p relative to the set of all the worlds W under consideration, a sum weighted by the credence that the agent assigns to each possible world:

The agent should then assign a credence to p that maximizes the expected accuracy of cr(p).Footnote 10 The issue that I will be concerned with is the set of worlds W that is used in the determination of accuracy. In order to determine expected accuracy, we must sum over the local inaccuracies at each possible world. Which possible worlds are these? Competing answers to this question give dramatically different verdicts on what credences a rational agent ought to have.

3 Accuracy over which worlds?

3.1 Metaphysically possible worlds

Consider the judgments our accuracy measure would give if we held that W is the set of all the metaphysically possible worlds. If this were the case, then the credence function that best maximized expected accuracy would be the one that assigns the highest credence to each and every metaphysical truth, for there will be no worlds in W in which these are false. This, of course, is an implausible result, as it would make it rationally required to assign a credence of one to all metaphysical necessities, including a posteriori necessities like that water is H20. Requiring a credence of one in all metaphysical truths is thus too stringent.

Now of course putting this view on Credence First theorists is disingenous due to its transparent shortcomings, but entertaining it reveals the difficulties that arise when selecting an appropriate set of worlds over which to assess accuracy. These problems come about because the set of metaphysically possible worlds is not connected in the right way to the agent’s first-person point of view. Recall that, according to Joyce, expected accuracy should be determined by a subject’s best judgment, and according to Leitgeb and Pettigrew, from an internalist point of view. But a subject’s best judgment does not vindicate the thought that the metaphysically possible worlds are the ones under consideration, and therefore requiring them to assess their accuracy from the perspective of metaphysical possibility is too demanding. From the subject’s point of view, they cannot distinguish all the metaphysically possible worlds from the impossible, nor should they be able to given their evidence and reasoning powers. Thus, the core problem that I will be focusing on is the challenge of Evidential Parity:

Evidential Parity—When an agent possesses equally strong evidence for two propositions p and q, the agent ought to assign equal credence to p and q

Evidential Parity worries arise for the metaphysically possible worlds proposal at several junctures. The first kind of situation in which such worries can arise are Cases of Ignorance where an agent has no reason to favor either p or q. Suppose, for example, that a philosophy student has no reason to favor one analysis of causation over another even though one is metaphysically necessary and the other impossible. The proposed analyses are on an evidential par for the student, and to assign one a higher credence than the other would be positively irrational. The same problem can arise in Cases of Equally Strong Evidence. Consider a student who is not clueless but instead has good evidence for both p and q where p concerns an analysis of causation and q an analysis of knowledge. The student has equally strong evidence for both, perhaps reasoning through potential counterexamples or depending on the testimony of their professors. Like before though, it turns out that one of the proposals is metaphysically necessary and the other impossible. On the current proposal, the student should assign a higher credence to the necessary proposition than to the impossible proposition, but this clearly flies in the face of Evidential Parity. Thus, measuring expected accuracy over all the metaphysically possible worlds requires agents to assign irrationally high credences, ones that go beyond the evidence they have for those propositions.

3.2 Epistemically possible worlds

A set of worlds that hews closer to an agent’s first person perspective, and the one endorsed by Leitgeb and Pettigrew, is the set of epistemically possible worlds:Footnote 11

We do not want to presuppose that the agent knows which world...is the actual world. Instead, the agent should take into account inaccuracies with respect to all and only the worlds that are epistemically possible for her; if this set is taken to be epistemically accessible to her, then we do not violate internalism about justification by demanding that she assess her overall inaccuracy in terms of it.Footnote 12

According to Leitgeb and Pettigrew, then, epistemic possibility is connected to the subject’s perspective in the right way for determining accuracy, making W the set of epistemically possible worlds. Let’s assess this proposal. A standard view on epistemic possibility goes as follows:

Epistemic Possibility—It is epistemically possible for S that p only if p is compatible with what S knowsFootnote 13

The epistemic possibility proposal, provides a definite improvement over the metaphysical possibility proposal. Cases of Ignorance, in particular, are no longer a problem. If my evidence concerning the correct analysis of causation is equally indifferent, then because I lack knowledge that either analysis is correct, they are both epistemically possible for me. Then, when I am assessing my expected accuracy, I can assign equal credence to both analyses. In this way, Leitgeb and Pettigrew can answer the Cases of Ignorance worry created by metaphysically possible worlds.

4 Challenge 1: Cases of equally strong evidence

A plausible route, then, for the Credence First theorist to avoid violating Epistemic Parity in Cases of Ignorance however, is to measure accuracy over all the epistemically possible worlds. Even though Leitgeb and Pettigrew’s proposal makes headway on Cases of Ignorance, it nevertheless still encounters issues with certain Cases of Equally Strong Evidence. Let’s look a bit more carefully at Epistemic Possibility. What exactly does this compatibility with what S knows come to? The standard view is that, at the very least, knowing that p makes it epistemically impossible that \(\lnot \)p. On this way of understanding compatibility, rational agents should have the highest credence in everything that they know, for all the epistemically possible worlds are those in which what they know is true. A prediction, then, of Leitgeb and Pettigrew’s view is that rational agents should have a credence of one in all the propositions that they know.

Because justification is fallible, however, it is possible that two propositions p and q are on a justificatory par for an agent, indeed that the agent is rational in believing that they know both p and q, and yet q ends up false while p is true. Suppose that I have a friend who regularly relays hockey scores to me. In all past cases, I have come to know the scores of the games, sometimes even checking independently whether my friend was correct. When my friend tells me a score, because my evidence is of the same sort for each score that my friend reports, I should assign an equivalent credence to each score being correct. Nevertheless, it could turn out on occasion that my friend is mistaken—they are correct about p, that the first score is 5-2, but incorrect about q, that the second score is 2-0. Because p is true, I come to know that p, making \(\lnot \)p epistemically impossible, but because q is false, \(\lnot \)q is epistemically possible because \(\lnot \)q is true. According to the epistemic possibility proposal then, I should have a different credence in p and q, for \(\lnot \)q is epistemically possible whereas \(\lnot \)p is not. From the subject’s point of view, however, I have equally strong evidence in both p and q—the only difference between them is their truth values. I should be equally confident in each of the scores that my friend has reported.

Leitgeb and Pettigrew are thus saddled with an unpalatable result. The problem arises because, on the standard view of epistemic possibility, knowing that p rules out \(\lnot \)p. This opens up the possibility that, even when two propositions are on a justificatory par, one can end up being epistemically possible and the other impossible. This result does not change on updated versions of Epistemic Possibility. In improving on Hacking’s (1967) proposal, DeRose appeals to the flexibility of the relevant community in determining what is epistemically possible. DeRose (1991) thinks that the relevant knowers in a situation will always include the speaker, making the speaker’s knowledge capable of ruling out a proposition as epistemically impossible (p. 596). Thus, on DeRose’s view as well, if a subject knows that p, it will be epistemically impossible that \(\lnot \)p. Of course, such a simplistic, speaker-centered variety of epistemic possibility has fallen out of favor—as MacFarlane (2011) points out, “practically no one who has staked out a serious position on the semantics of epistemic modals defends the view” (p. 150). Maybe the advocate of problem, then, with this understanding of Leitgeb and Pettigrew’s proposal is the simplistic, outdated version of Epistemic Possibility.

So can Leitgeb and Pettigrew, by adopting a more complex notion of epistemic possibility, avoid the problematic Cases of Equally Strong Evidence? The answer here is a definitive no. Because we are interested in the agent’s perspective, we are focused on the worlds that a person themselves counts as epistemically possible. And all plausible accounts of epistemic possibility, when evaluated from the speaker’s point of view, are restricted by the knowledge of the speaker. Consider the two players in the current debate, contextualism and relativism. On the contextualist view, judgments of epistemic possibility are evaluated according to the knowledge of a salient group that includes the speaker.Footnote 14 This view obviously restricts the scope of epistemic possibility by the knowledge of the speaker, providing room to formulate worrisome Cases of Equally Strong Evidence. On the relativist view, epistemic possibility is constrained by the knowledge of the assessor of an epistemic modal.Footnote 15 In cases of eavesdropping, this can make the space of epistemically possible worlds come apart from those circumscribed by the knowledge of the speaker, but in the cases we are worried about, self-evaluations of epistemic possibility, the epistemically possible worlds will always be limited by the speaker’s knowledge. Any potential issues with for simple, speaker-oriented views, then, do not undermine the claim needed for the argument in this section—that at the very least, speaker knowledge that p makes it epistemically impossible that \(\lnot \)p when the speaker is evaluating things from their own perspective.

5 Challenge 2: Epistemic possibility and knowledge

We have seen that, even if appealing to epistemic possibility provides an answer to worries about Cases of Ignorance, such a view nevertheless falls prey to certain Cases of Equally Strong Evidence. A further, and perhaps more damning problem with appealing to epistemic possibility, is that it may abandon the Credence First project altogether. Epistemic Possibility is defined in terms of knowledge, a normatively-loaded concept. If what one knows in part determines what credences are rational, then this runs the risk that credal norms will not be the most fundamental epistemic norms. It turns out this worry is well warranted. The two most popular ways of understanding the knowledge concept—JTB+ and Knowledge First—are incompatible with being Credence First. Taking the JTB+ route yields a Belief First view, while Knowledge First is committed to Independence.

5.1 Knowledge as justified true belief+

The historically dominant view within epistemology is that knowledge is to be analyzed as justified true belief plus some condition to avoid Gettier cases. If this is the correct view of knowledge, then the normativity of knowledge derives from that of belief—there are norms that must be satisfied to know because there are norms that must be satisfied in order to have a justified belief. This, however, places belief norms before credal norms. On this picture, what grounds whether one knows is whether one has a justified belief, and thus to adopt an epistemic possibility interpretation of credal accuracy would require that rational beliefs are more fundamental than rational credences. The resulting picture can be seen in Fig. 3:

This is clearly not a Credence First picture. If Leitgeb and Pettigrew opt for Epistemic Possibility and understand knowledge as JTB+, then they are actually committed to Belief First. On this way of understanding knowledge, what one is justified in believing determines what one knows, and this then grounds what credences are accurate. This is just to vindicate the traditional epistemologist—what is most important is investigating the norms on belief, for these determine both what is known and what credences are rational.

5.2 Knowledge first

A contemporary rejoinder to the hegemony of the JTB+ picture is Knowledge First, the view that knowledge cannot be analyzed in terms of other concepts. On this view, JTB+ came up short by trying to break knowledge down into separate components. The right approach, rather, is to give an account of other epistemic notions in terms of knowledge.Footnote 16 The normative picture, then, proceeds in reverse. Instead of understanding what is known in terms of what one is justified in believing, what is justified to believe is accounted for in terms of what is known. Some accounts of justified belief that have been offered in this vein include the following:

Actual Knowledge—S justifiedly believes that p if and only if S knows that pFootnote 17

Potential Knowledge—S justifiedly believes that p if and only if there is a world where S has the same mental states and beliefs and knows that pFootnote 18

On both Actual Knowledge and Potential Knowledge, the relationship between knowledge and justified belief is conceptually distinct from the JTB+ analysis. On these views, beliefs are justified because they qualify, or potentially qualify, as knowledge, not the other way around. Thus, Knowledge First shifts the order of explanation, making knowledge more fundamental than belief norms.

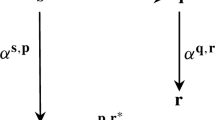

The Knowledge First account of the relationship between knowledge and justified belief allows Leitgeb and Pettigrew to escape being Belief First. There is no appeal to justified belief to ground what is known, and thus no need to have an account of justified belief in order to determine what credences are accurate. By being Knowledge First, Leitgeb and Pettigrew need not take belief norms to be most fundamental. Instead, the resulting picture now looks like Fig. 4:

The problem with the Knowledge First view is that, even though it allows Leitgeb and Pettigrew to escape the Belief First conclusion, it instead ends up vindicating Independence. On Knowledge First, knowledge is the fundamental epistemic concept, giving rise to both belief norms and credal norms. The Knowledge First view of justified belief explains justified belief in terms of knowledge. Likewise, if Leitgeb and Pettigrew are right to measure accuracy over the epistemically possible worlds, then rational credence will also be explained in terms of knowledge. This, however, is not to participate in the Credence First project of reducing belief norms to credal norms. Instead, neither credal norms nor belief norms are more fundamental–knowledge is the most basic and explains the norms of both belief and credence. For this reason, a Knowledge First need not think that all instances of knowledge are also instances of justified belief interpretation of Leitgeb and Pettigrew will also not preserve the Credence First project of the revolutionary epistemologist.Footnote 19

Maybe the advocate of Knowledge First need not think that all instances of knowledge are also instances of justified belief. Another possibility is to hold that it is possible to have knowledge that p while nevertheless being unjustified in believing that p.Footnote 20 Lasonen-Aarnio has argued, for example, that it is possible to have knowledge that p in the face of higher-order evidence to the contrary, calling such instances cases of “unreasonable knowledge.” In these cases, a person can know even if it is unlikely on their evidence that they do, preserving knowledge in some cases of higher-order defeat.Footnote 21 If we suppose that these instances of unreasonable knowledge are also cases of unjustified belief, then we can argue that Fig. 4 might not tell the whole story when it comes to the relationship between knowledge and justified belief.

This position, however, does nothing to establish that appealing to epistemic possibility will help Credence Firsters give an intuitive account of rational credence or justified belief. To begin with, if a person knows that p, even unreasonably, then it will be epistemically impossible for them that \(\lnot \)p, requiring that they assign a credence of one to p. But if it is unreasonable for them, given their evidence, to believe that p, then it is also seems incorrect to say that their evidence rationalizes a credence of one. At best, such evidence would seem to only warrant a middling credence in p rather than complete certainty. Furthermore, if a credence of one is required in such cases, then this undermines the connection between rational credence and justified belief. If it is rational to assign a credence of one to p, then surely the Credence First position must hold that it is also justified to believe that p. After all, if credence one is not enough to justify belief, then there is no greater credence that could then make a belief justified. However, we have already assumed from the outset that believing that p in cases of unreasonable knowledge is unjustified, decoupling the link between rational credence and justified belief.

6 Conclusion

In recent years, revolutionary epistemologists have claimed that credal norms are the most fundamental variety of epistemic norms. In this paper, I have shown that, at least for epistemic possibility varieties of expected accuracy proposals, such a move is too hasty. Measuring accuracy over the epistemically possible worlds fails to do justice to Cases of Equally Strong Evidence, and the very notion of epistemically possible worlds calls into question the fundamentality of credal norms.

Even though epistemic possibility will not be of use, there may be other accounts of possibility that can vindicate the claims made by revolutionary epistemologists. In recent work, Robbie Williams explores an account of doxastic possibility that hopes to account for logical uncertainty, while Pettigrew uses an account of personal possibility to make sense of logical learning. Both of these types of possibility are distinct from epistemic possibility. Pettigrew says that “a world is personally possible not if it makes true all you know or believe, but rather if it hasn’t been ruled out by your cognitive activities and processes,”Footnote 22 and Williams makes it clear that the notion of doxastic possibility he has in mind need not be co-extensive with epistemic possibility.Footnote 23 Epistemic possibility is incapable of vindicating the project of revolutionary epistemology, but there may still be a route to arguing that credal norms are the most fundamental.

Notes

Harman (1986) comes closest to explicitly adopting this view, arguing that reasoning requires principles of belief revision rather than principles that regulate credences (pp. 21–23 and 104). Holton (2014) holds that limited creatures like us need beliefs rather than credences for practical deliberation (pp. 13–14).

Even though many of the epistemologists that emphasize accuracy fall into the Credence First camp, this is not inevitable. There have been a number of recent proposals, for example, that have explored the accuracy of belief, including Dorst (2019), Easwaran (2016), Pettigrew (2016b, 2017), and to a lesser extent, Fitelson and Easwaran (2015). Thus, what I have to say in this article will not target all that hope to ground epistemic norms in accuracy considerations, but only those who hope to defend Credence First using this paradigm. For more on the application of the accuracy paradigm to belief, see Siscoe (Forthcoming).

See Joyce (1998), p. 579.

See Leitgeb and Pettigrew (2010), p. 202.

See Schoenfield (2015), p. 653.

Leitgeb and Pettigrew (2010) say as much, noting that, on suitable transformations, minimizing inaccuracy is synonymous with maximizing accuracy (p. 203, fn. 2).

See Leitgeb and Pettigrew (2010), p. 207.

Of course maximizing the accuracy of a credence in a particular proposition should not be confused with maximizing the accuracy of an agent’s entire credence function, but this bare outline will be sufficient for the purposes of our discussion. For how the approach to maximizing the accuracy of an entire credence function differs from maximizing the accuracy of a credence in a single proposition, see Leitgeb and Pettigrew’s (2010) distinction between local and global inaccuracy measures (pp. 205–207).

Another popular suggestion has been that accuracy should be measured over the a priori possible worlds, but measuring expected accuracy over the a priori possible worlds still violates Evidential Parity in cases of ignorance. The analyses that the student was considering in our former examples are not just metaphysically necessary or impossible, either they or their negations are also knowable a priori. Furthermore, the a priori proposal requires not only assigning a credence of one to all conceptual truths, but to all logical and mathematical truths as well. Some have attempted to defend such requirements by appealing to a notion of ideal rationality—see Christensen (2004), pp. 151–152, Hawthorne and Bovens (1999), p. 257, and Smithies (2015), p. 2780—but since the primary purpose of this paper is evaluating the Leitgeb and Pettigew proposal, I will not have the space here to consider such views.

See DeRose (1991), pp. 593–594, Hacking (1967), p. 153, and Kratzer (1981, 1991). This is not the most recent proposal for capturing epistemic possibility, but it will be sufficient for our purposes. For an argument that updated analyses of epistemic possibility will not effect the argument against Leitgeb and Pettigrew, see Sect. 4.

See Williamson (2000).

This account is advanced by Bird (2007).

It might seem like Moss’s (2013) theory of probabilistic knowledge offers a route out of this difficulty as, on Moss’s view, credences can constitute knowledge. This is only, however, a way to delay the difficulty. If the knowledge appealed to in Epistemic Possibility is credal knowledge, then the question remains of how those credences were rational to hold in the first place.

Thank you to an anonymous reviewer for suggesting that I consider the possibility of knowledge without justification.

See Pettigrew (2021), p. 9995.

See Williams and Robert (2018), pp. 134–135.

References

Ball, B. (2013). Knowledge is normal belief. Analysis, 73, 69–76.

Baker-Hytch, M., & Benton, M. (2015). Defeatism defeated. Philosophical Perspectives, 29, 40–66.

Bird, A. (2007). Justified judging. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 74, 81–110.

Buchak, L. (2014). Belief, credence, and norms. Philosophical Studies, 169, 285–311.

Christensen, D. (2004). Putting logic in its place: Formal constraints on rational belief. Oxford University Press.

DeRose, K. (1991). Epistemic possibilities. The Philosophical Review, 100(4), 581–605.

Dorr, C., & Hawthorne, J. (2013). Embedding epistemic modals. Mind, 488, 867–913.

Dorst, K. (2019). Lockeans maximize expected accuracy. Mind, 128, 175–211.

Dowell, J. L. (2011). A flexible contextualist account of epistemic modals. Philosophers’ Imprint, 11, 1–25.

Easwaran, K. (2016). Dr. truthlove or: How I learned to stop worrying and love Bayesian probabilities. Nous, 50, 816–853.

Egan, A. (2007). Epistemic modals, relativism, and assertion. Philosophical Studies, 133, 1–22.

Egan, A., Hawthorne, J., & Weatherson, B. (2005). Epistemic modals in context. In G. Preyer & G. Peter (Eds.), Contextualism in philosophy. Oxford University Press.

Fitelson, B., & Easwaran, K. (2015). Accuracy, coherence and evidence. Oxford Studies in Epistemology, 5, 61–96.

Frankish, K. (2004). Mind and supermind. Cambridge University Press.

Frankish, K. (2009). Partial belief and flat-out belief. In F. Huber & C. Schmidt-Petri (Eds.), Degrees of belief (pp. 75–93). Berlin: Springer.

Hacking, I. (1967). Possibility. The Philosophical Review, 76, 143–168.

Harman, G. (1986). Change in view: Principles of reasoning. NY: MIT Press.

Hawthorne, J. (2007). Eavesdroppers and epistemic modals. Philosophical Issues, 17, 92–101.

Hawthorne, J., & Bovens, L. (1999). The preface, the lottery, and the logic of belief. Mind, 108, 241–264.

Holton, R. (2014). Intention as a model for belief. In M. Vargas & G. Yaffe (Eds.), Rational and social agency: Essays on the philosophy of Michael Bratman (pp. 12–37). Oxford University Press.

Jeffrey, R. (1970). Dracula meets Wolfman: Acceptance vs. partial belief. In M. Swain (Ed.), Induction, acceptance, and rational belief. D. Reidel.

Jeffrey, R. (1992). Probability and the art of judgment. Cambridge University Press.

Joyce, J. (1998). A nonpragmatic vindication of probabilism. Philosophy of Science, 65(4), 575–603.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H.-J. Eikmeyer & H. Rieser (Eds.), Words, worlds, and contexts. New approaches in word semantics (pp. 38–74). de Gruyter.

Kratzer, Angelika. (1991). Modality. In A. von Stechow & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research (pp 639–665). de Gruyter.

Lasonen-Aarnio, M. (2010). Unreasonable knowledge. Philosophical Perspectives, 24, 1–21.

Leitgeb, H., & Pettigrew, R. (2010). An objective justification of Bayesianism I: Measuring inaccuracy. Philosophy of Science, 77(2), 201–235.

Littlejohn, C. (2013). The Russellian retreat. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 113, 293–320.

MacFarlane, J. (2011). Epistemic modals are assessment sensitive. In A. Egan & B. Weatherson (Eds.), Epistemic modality. Oxford University Press.

MacFarlane, J. (2014). Assessment-sensitivity: Relative truth and its applications. NY: Oxford University Press.

Moss, S. (2013). Epistemology formalized. Philosophical Review, 122, 1–43.

Pettigrew, R. (2016). Accuracy and the laws of credence. Oxford University Press.

Pettigrew, R. (2016). Jamesian epistemology formalized: An explication of ‘The will to believe’. Episteme, 13, 253–268.

Pettigrew, R. (2017). Epistemic utility and the normativity of logic. Logos and Episteme, 8, 455–492.

Pettigrew, R. (2021). Logical ignorance and logical learning. Synthese, 198(10), 9991–10020.

Ross, J., & Schroeder, M. (2014). Belief, credence, and pragmatic encroachment. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 88, 259–288.

Savage, L. (1954). The foundations of statistics. Wiley.

Schoenfield, M. (2015). Bridging rationality and accuracy. The Journal of Philosophy, 112(12), 633–657.

Siscoe, R. W. (Forthcoming). Accuracy across doxastic attitudes: Recent work on the accuracy of belief. American Philosophical Quarterly.

Smithies, D. (2015). “Ideal Rationality” and logical omniscience. Synthese,192(9), 2769–2793.

Sturgeon, S. (2008). Reason and the grain of belief. Nous, 42, 139–165.

Sutton, J. (2005). Stick to what you know. Nous, 39, 359–396.

Sutton, J. (2007). Without Justification. MIT Press.

Weatherson, B. (2014). Games, beliefs and credences. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 88, 209–236.

Wedgwood, R. (2012). Outright belief. Dialectica, 66, 309–329.

Williams, J., & Robert, G. (2018). Rational illogicality. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 96(1), 127–141.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williamson, T. (2011). Knowledge first epistemology. In S. Bernecker & D. Pritchard (Eds.), The Routledge companion to epistemology. Routledge.

Yanovich, I. (2014). Standard contextualism strikes back. Journal of Semantics, 31, 67–114.

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper, I am indebted to Charity Anderson, Richard Clarke, Daniel Greco, Liz Jackson, Chad Marxen, Richard Pettigrew, Julia Staffel, Greta Turnbull, and an audience at the 2021 Central Division Meeting of the American Philosophical Association.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Siscoe, R.W. Credal accuracy and knowledge. Synthese 200, 163 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03636-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03636-8