Abstract

It has been argued recently that one major difficulty facing the A-theory of time consists in the view’s failure to provide a satisfactory account of the passage of time. Critics have objected that this particular charge is premised on an unduly strong conception of temporal passage, and that the argument does not go through on alternative, less demanding conceptions of passage. The resulting dialectical stalemate threatens to prove intractable, given the notorious elusiveness of the notion of temporal passage. Here I argue that there is progress to be made in this regard. The argument from passage takes issue with a certain feature of the standard versions of the A-theory that is in fact problematic independently of worries about temporal passage. To illustrate this, I present a new argument, the argument from comprehensiveness, which demonstrates that the standard A-theoretic account of temporal reality is inadequate, even if it is granted that it can accommodate passage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In a highly influential recent paper, Kit Fine (2005) has argued that one major problem with the A-theory of time, as commonly conceived, is that it fails to offer a satisfactory account of temporal passage.Footnote 1 Although Fine’s argument has drawn considerable attention, many appear to remain unimpressed by it: in particular, critics have remarked that A-theorists usually work with a different conception of temporal passage, one which apparently allows them to vindicate the passage of time. Given the notorious elusiveness of the notion of passage, the current state of the dialectic gives one little hope of progress. My central aim in this paper is to argue that the case against the standard version of the A-theory can be strengthened by means of a different argument, the argument from comprehensiveness. This new argument spotlights the same underlying deficiency in the standard A-theoretic account as Fine’s objection but shows that it has disastrous consequences even independently of worries about accommodating passage. In the next section, I outline the background to Fine’s objection, and then, in Sect. 3, I briefly examine the argument from passage as well as some responses to it. In Sect. 4, I present the argument from comprehensiveness in a rather compact form, and then elaborate on some details in Sects. 5 and 6, when addressing two general strategies for resisting the argument.

2 Fine’s McTaggart and realism about tense

Fine presents the argument from passage against the backdrop of his reconstruction of McTaggart’s (1908) infamous argument against the A-theory and a discussion of possible responses to it. On Fine’s view, the dispute between A-theorists and B-theorists hinges on the question of whether, among the facts that constitute the fundamental way reality is, there are some that are genuinely tensed. Thus, A-theorists accept, and B-theorists reject, the following claim:

realism

Reality is fundamentally constituted by tensed facts.

Accordingly, A-theorists are realists, and B-theorists anti-realists, about tensed facts.Footnote 2 Fine (2005, p. 271) further argues that the kernel of truth behind McTaggart’s paradox is that realism clashes with three general theses about the nature of reality and its constitution by facts.Footnote 3 These read as follows, in slightly altered and/or truncated form:

neutrality*

No time is privileged, the tensed facts that constitute reality are not oriented towards one time as opposed to another.

absolutism

The constitution of reality is an absolute matter.

coherence

Reality as a whole is coherent.

neutrality* might initially seem to be a non-starter in the context of realism about tense. For, however exactly they are to be construed, tensed facts appear to relate to time in a peculiar, twofold manner. If the tensed fact that a was F obtains, for instance, it will be anchored at the time at which its obtaining takes place, although it is directed at an earlier time. Thus, contrary to what neutrality* could be taken to mean, there is a sense in which any tensed fact is essentially ‘oriented’ towards a certain time as opposed to others, towards the one at which it is anchored—a tensed fact cannot be time-neutral in this particular sense.Footnote 4 But Fine’s (2005, p. 271) comments about neutrality* make clear that this is not the intended meaning anyway: “What [neutrality*] means … in the present case, is that there should be no privileged time t for which the totality of tensed facts constituting reality are ones that obtain at t”. Thus, what neutrality* is supposed to rule out is that there is a single unique time at which all the tensed facts are anchored, not anchoring or orientation itself. To make this reading more explicit, we can reformulate neutrality* as follows:

neutrality

No time is privileged as the unique locus of obtainment of tensed facts that constitute reality.

To see why realism is incompatible with the joint acceptance of these three theses, consider a very simple ‘B-theoretic’ universe hosting only one single spatiotemporal entity, Fido. Fido exists at only three times and has a different uniform colour at each of them: he is yellow all over at t 1, brown all over at t 2, and blue all over at t 3 (Fig. 1).Footnote 5 Suppose that we wish to translate this story into one that involves tensed rather than tenseless facts. We first focus our gaze on what goes on at t 2 and come across the present-tensed fact that Fido is brown. But given neutrality, we also need to examine the other two times Fido’s story involves; and once we do so, we encounter two further present-tensed facts anchored at those respective times: the fact that Fido is yellow as well as the fact that Fido is blue. Assuming that the glow around the individual pictures of Fido represents the present-tensedness of the relevant fact, Fig. 2 is what we end up with. Now, absolutism requires that each of these facts be taken to constitute reality in an absolute fashion—relativising the constitution of reality by these facts to the respective times at which they are anchored is thereby prohibited. But this means that the tensed version of Fido’s adventures turns out to violate coherence: absolutely speaking, Fido presently is yellow all over, and brown all over, and blue all over.

One response to the argument, endorsed by proponents of what Fine calls standard realism, consists in simply rejecting neutrality. This calls for a radical revision of Fig. 2. Suppose that t 2 is the unique locus of obtainment the standard realist believes in. Given this, the standard realist will first get rid of any tensed facts that are supposed to obtain at times other than t 2. Thus, the facts that Fido is yellow, and that Fido is blue, both of which are represented in Fig. 2, will have to go. Since all facts are anchored at t 2, the standard realist’s picture also does not seem to require the timeline included in Figs. 1 and 2.Footnote 6 But even though the standard realist’s picture excludes these elements of the previous pictures, it will include facts about Fido obtaining at t 2 yet directed at t 1 and t 3: the past-directed fact that Fido was yellow and the future-directed fact that Fido will be blue. Assuming that fadedness symbolises the past-directedness and blurriness the future-directedness of the relevant facts, Fig. 3 corresponds to the standard realist’s picture of reality.

Standard realism is aptly named, as most existent versions of realism about tense, or the A-theory, seem to subscribe, in one way or another, to the idea of a privileged time as the unique locus of obtainment. But rejecting neutrality is not the only possible response to Fine’s version of the argument. A realist may, for instance, opt to endorse Fig. 2 as a basically accurate depiction of Fido’s universe, which amounts to giving up coherence, the idea that reality as a whole is something whose parts ultimately turn out to be compatible with one another. Alternatively, one may reject absolutism instead and reinterpret Fig. 2 as a (perhaps misleading or even distorted) collage of different temporally relative ways reality is: on this view, Fido’s adventures do not translate into one single tensed story, but rather irreducibly involve distinct temporal perspectives. In the Finean taxonomy, these two approaches, fragmentalism and external relativism, respectively, count as versions of non-standard realism.Footnote 7

3 The argument from passage

Each variant of realism outlined in the previous section can avoid the McTaggartian argument without further ado. But Fine goes on to argue that standard realism is in fact the worst option for the realist, and he objects to the view from a somewhat unexpected angle. A-theorists often pride themselves in having attained what is something of a holy grail of metaphysics of time: accommodating the passage of time. Fine’s argument from passage alleges, however, that there is little reason to be excited about standard realism if defending the reality of temporal passage is the goal.Footnote 8 While invoking a single, absolutely privileged locus of obtainment for tensed facts constitutes an effective response to the McTaggartian argument, Fine (2005, p. 286; 287) argues, it also deprives the standard realist of the tools required to account for passage:

[A] thought commonly had by realists is that … for time to pass from one moment to the next is for a property of presentness to pass from one moment to the next … But although the standard realist can grant that there is such a property, his metaphysics makes it entirely unsuited to accounting for the passage of time … [F]or the passage of time requires that the moments of time be successively present and this appears to require more than the presentness of a single moment of time.

To appreciate Fine’s point, consider once again Fig. 3. The standard realist claims that what we see in this picture is all there is to Fido’s universe: it depicts the absolute way Fido’s universe is, as constituted by the three tensed facts anchored at the unique locus of obtainment t 2. This picture appears to incorporate, by means of the distinction between the past-, present-, and future-directedness of the facts it represents, the idea that temporal reality ‘objectively’ divides into distinct temporal zones. But temporal passage seems to require that the boundaries of those past, present, and future realms not be fixed, but rather subject to constant change, and it is highly doubtful, Fine (2005, p. 287) argues, that the mere existence of past- and future-directed facts is sufficient to set those distinct temporal zones into motion:

We naturally read more into the realist’s tense-logical pronouncements than they actually convey. But his conception of temporal reality, once it is seen for what it is, is as static or block-like as the anti-realist’s, the only difference lying in the fact that his block has a privileged centre. Even if presentness is allowed to shed its light upon the world, there is nothing in his metaphysics to prevent that light being ‘frozen’ on a particular moment of time.

But there is in fact a tradition, which goes back at least to Prior (2003) and seems to be reflected in several unfavourable responses to Fine’s argument, that assigns primary significance to certain “tense-logical pronouncements” when it comes to accommodating temporal passage. On this rather ‘thin’ conception of passage, there is nothing more to passage than things’ presently being a certain way and their having been some other way. Figure 3, for instance, depicts a world in which time passes, simply because it tells us that, presently, Fido is brown, but used to be yellow—such claims are supposed to be, as Pooley (2013, p. 329) puts it, “all that the [standard realist] needs to express the passage of time.” Relatedly, Deasy (2018, p. 282) claims that Fine’s argument fails because, in designating some particular time as the unique locus of obtainment, standard realists do not commit to some sort of ‘sempiternal present’, a time that is, has always been, and will always be present:

According to the ‘frozen’ A-theory, the present instant is always present … A-theorists can easily distinguish their view from the ‘frozen’ A-theory: their view has an implication—namely, that there are instants that were and will be present—that the ‘frozen’ A-theory does not.

According to this line of thought, then, the mere existence of past- and future-directed facts about how things were and will be different than they presently are makes standard realism ‘dynamic’ instead of ‘static’.Footnote 9 Fine, on the other hand, is well aware that such facts are available to the standard realist and that they can serve to distinguish her account from one with a sempiternal present. The question is, however, whether they are really sufficient for dynamicity and whether a sempiternal present is necessary for staticity. Fine’s point is that the reality of temporal passage implies a reality in transition, one where presentness is genuinely being passed on from one time to the next; and on his view, this transition cannot be captured by a metaphysics that features a single, absolutely unique locus of obtainment. From this perspective, the standard realist’s account with the relevant past- and future-directed facts seems to constantly promise the required sort of succession without ever truly delivering it.

We thus seem to have reached a dialectical impasse, one that threatens to prove difficult to overcome, considering how profoundly elusive the notion of temporal passage is. But I think that progress can be made on this front. There is actually more to the worry about passage than first meets the eye—in particular, the argument takes issue with a characteristic of standard realism that does indeed constitute a fatal flaw: the absence of non-presently anchored facts. But exactly what is wrong with this can be brought out by means of a different argument, one that does not appeal to a robust notion of passage and therefore promises to be dialectically more effective and harder to resist.

4 The argument from comprehensiveness

Figures 1 and 3 visualise, respectively, the B-theorist’s and the standard realist’s accounts of Fido’s world. There are a number of different criteria along which we can compare such depictions, but let us consider here the following three:

content

Is the content of the depiction tensed or tenseless? Are the depicted facts meant to be tensed or tenseless?

character

Does the depiction have an absolute or relative character? Are the depicted facts to be understood as obtaining absolutely, or relative to a temporal standpoint?

scope

Is the depiction partial or comprehensive in scope? Are the depicted facts supposed to exhaust all the facts constituting reality, or to correspond only to a subclass of them?

Now, one obvious difference between Figs. 1 and 3 is with respect to content: the former represents tenseless facts, while the latter has tensed content. But these depictions are not supposed to differ with respect to character and scope. Given that standard realists endorse absolutism, Fig. 3, just like Fig. 1, is meant to represent how reality is, absolutely speaking, or simpliciter, not just how reality is relative to this or that temporal standpoint. Figure 3 is also meant to be comprehensive in scope: it purports to depict, just like Fig. 1, how temporal reality is in Fido’s world in its full entirety. That pictures like Fig. 3 are supposed to be absolutely comprehensive is nicely highlighted by Cameron (2015: 75), himself a card-carrying standard realist, with an example similar to Fido’s adventures:

Suppose we are at the second moment of a three-moment history: so time t2 is present, t1 is past, and t3 is future. Suppose further that there are only two temporary ways for things to be in this world: redness can ensue, or blueness can ensue. Lastly, suppose that redness presently ensues, but that blueness did ensue and will ensue again … Let us represent … blueness ensuing at a time by writing the name of that time in bold and represent redness ensuing at a time by writing the name of that time not in bold. Represent a time being present by underlining the name of that time … [L]et us put a star next to the name of a time to represent that it is present at that time. Then we can completely and accurately represent this world as follows:

t1* t2* t3*.

Nothing is missing from this diagram: it tells you everything you need to know about reality.Footnote 10

Now, just like the world in Cameron’s scenario, Fido’s world, too, is a non-instantaneous one—his adventures take place over the period of time from t 1 to t 3. Thus, the way Fido’s world fundamentally is, in its full entirety, is the way it fundamentally is within the relevant period of time. There may be a single fundamental way how temporal reality is from t 1 to t 3, but if there are multiple distinct ways how it is throughout this period, then each of those ways will have to be taken to be relevant for the comprehensive story we wish to tell about the way reality is. In other words, if there is such a plurality of how reality is within a period of time, then none of the fundamental ways reality is can legitimately be singled out as the way reality is in its full entirety in that period—that sort of bias towards one way that reality is and against the others would certainly be arbitrary, and therefore unacceptable. This idea is encapsulated by the following principle:

diachronic comprehensiveness (dc)

The fundamental way reality is in its full entirety over some period of time incorporates each and every fundamental way reality is within that period of time.

It is worth emphasising that dc does not require that there be a single, over-arching way reality fundamentally is over some period of time; incorporation need not mean integration. If one believes there to be various distinct fundamental ways reality is over some period of time, then dc merely requires that they all figure in some form in one’s account of the fundamental way reality is in its full entirety over that period—that is all. dc thus seems quite harmless and uncontroversial.

Given dc, we can spell out somewhat more specifically what it takes for a depiction of how reality fundamentally is over some period of time to be comprehensive in scope:

diachronically comprehensive scope (dcs)

A representation of how reality fundamentally is over some period of time is diachronically comprehensive in scope if, and only if, each and every fundamental way reality is over that period of time somehow figures in it.

Just as dc does not require there to be a single, ultimate way reality fundamentally is over a period of time, it does not follow from dcs that there must be a single, all-encompassing picture of how reality is over some period.Footnote 11 One might very well think that, because there are multiple distinct ways reality is over a period of time, individual pictures of each of those distinct ways resist being integrated into a single, ultimate picture of how reality is over that period. Still, dcs does require from a representation of a non-instantaneous world that purports to be diachronically comprehensive that it somehow take into account each and every fundamental way reality is within the relevant period of time.

Both the B-theorist’s Fig. 1 and the standard realist’s Fig. 3, then, are meant to be absolutely comprehensive representations of Fido’s world; and given that they both purport to represent a non-instantaneous world, they need to comply with dcs. It is not difficult to see why dc and dcs do not cause any trouble for the B-theorist. The B-theorist believes that there is a single fundamental way how reality is within the period from t 1 to t 3, the way that is constituted by the tenseless facts represented in Fig. 1—hence, her account conforms to dc and dcs in a vacuous fashion. It might seem that an analogous response is available to the standard realist as well. Recall how Cameron claims that the single-rowed diagram in the passage quoted above tells us everything there is to know about the tensed reality in the world he discusses. Similarly, the standard realist might maintain that there is a single, fundamental way how things are in Fido’s world within the period from t 1 to t 3, namely the way things are represented to be by Fig. 3.

It is illusory, however, that accommodating dc and dcs is as straightforward a matter for the standard realist as it is for the B-theorist. Cameron’s single-rowed diagram, for instance, does not really seem to tell us everything we need to know about his three-moment history. Intuitively, a whole lot seems to be missing from it—exactly the two-thirds of the total tensed way reality is in the relevant three-moment history, in which t 1 and t 3 are also supposed to take their turn to be present. Once the parts that have been left out are added, the diagram looks like this:

t1* t2* t3*.

t1* t2* t3*.

t1 * t2* t3*.

Similarly, the tensed version of Fido’s adventures over the period from t 1 to t 3, in its full entirety, surely includes more than just the facts represented in Fig. 3: the fact that Fido is yellow, the fact that Fido is blue, the fact that Fido will be brown, or the fact that Fido was brown are all among the facts that get to constitute the tensed reality in Fido’s world over that period, yet none of them is represented by the picture in Fig. 3. Once the tensed story of how things fundamentally are in Fido’s world is expanded so as to be diachronically comprehensive, we get the picture in Fig. 4, with the columns to the left and to the right supplementing what was missing from Fig. 3.

Think of a non-instantaneous tensed world as a movie as it unfolds on a screen, with each of the images appearing on the screen one after another standing for a tensed way that this world is. The B-theorist believes that what is going on on the screen is grounded in a physical strip of film; her representation of how temporal reality fundamentally is is like a picture of a whole strip of film, whose individual frames would correspond to the B-theorist’s tenseless facts. The standard realist’s pictures like Fig. 3, on the other, resemble a snapshot of a single image as it appears on the screen. Perhaps the image that the standard realist happens to have captured by means of Fig. 3 truly deserves to be in focus; but, at any rate, it seems clear that there is more to the movie that is the tensed reality of Fido’s world than a single one of the images it incorporates.

There are two general ways in which the standard realist might attempt to resist the argument from comprehensiveness. First, the standard realist might admit that the above considerations do indeed pose a challenge yet argue that it can in fact be met. Alternatively, she might seek to dismiss the objection altogether, claiming that it just begs the question against her view. In the following two sections, we will discuss these strategies in turn and conclude that neither of them looks promising for the standard realist.

5 Sophisticating the present?

The proponent of the first type of response acknowledges the need to say more about how the standard realist’s representations of reality can be comprehensive in scope but believes that this task can be accomplished rather easily. Suppose that, as before, the standard realist initially offers Fig. 3 as her account of Fido’s world. She could then argue, in order to show that her account is in conformity with dc and dcs, that the columns to the left and to the right in Fig. 4 do not have the same temporal status as the one in the middle (which is of course the same as the picture in Fig. 3). While the column in the middle is a picture of the way reality presently is in Fido’s world, representing the facts that presently obtain, the other two columns depict the ways reality was or will be, representing the facts that have obtained but do no longer, or the facts that do not yet obtain but will. To illustrate this point, let us frame each of the columns in Fig. 4 in a different colour in order to represent the standard realist’s preferred temporal arrangement: if a column is framed in yellow, it is to be understood as representing the way reality presently is; if it is framed in blue, it is supposed to depict the way reality was; and finally, if it is framed in red, it is to be understood as a picture of the way reality will be. Thus, Fig. 5 shows how the standard realist interprets Fig. 4. The standard realist might claim that, while Fig. 3 may fail to represent the total tensed way things are in Fido’s world over the period of time from t 1 to t 3, Fig. 5 is diachronically comprehensive: after all, Fig. 5 does seem to incorporate all of the columns in Fig. 4, even though it assigns a different temporal status to each of them.

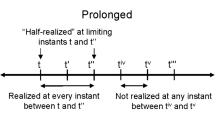

This response will not do, however. Let us first revisit the previous distinction between a tensed fact’s being directed at a time and its being anchored at a time. That distinction underlies two further distinctions, the one between mono- vs. multi-directed worlds and the other between mono- vs. multi-anchored worlds. A tensed world is mono-directed (mono-anchored) iff there is a single time at which all the facts that constitute it are directed (anchored) at, and multi-directed (multi-anchored) otherwise. With these distinctions in hand, we can rephrase the argument from comprehensiveness as follows. It seems natural to think that an instantaneous tensed world would be mono-directed and mono-anchored, and a non-instantaneous one like Fido’s multi-directed and multi-anchored. Given that a picture like Fig. 3 shows a mono-anchored world, however, it cannot, by itself, satisfy what dcs requires from a comprehensive representation of a non-instantaneous world.

But what about Fig. 5—does this more sophisticated picture fill the bill? To see that it does not, note that, when the standard realist says that the columns to the left and to the right in Fig. 4 represent facts that have obtained but do no longer or ones that do not yet obtain but will, she must still be talking, in a bit more elaborate fashion than before, about what is going on at t 2, the locus of obtainment she takes to be unique. Given her rejection of neutrality, the standard realist cannot but interpret Fig. 4 as an ‘enriched’ representation of the present reality already represented by Fig. 3, featuring only presently obtaining facts just as before. Figure 5 features more and more complex tensed facts than Fig. 3; yet this additional complexity still concerns the same mono-anchored way reality is that Fig. 3 depicts as well.Footnote 12

And this precisely is the reason why Fig. 5 does not amount to a genuinely comprehensive tensed version of Fido’s adventures. The particular temporal arrangement of the columns in Fig. 5, the blue–yellow–red pattern, is itself part of the way things presently are, constituted by facts that are exclusively anchored at t 2. But if the tensed reality in Fido’s world is to be represented at this level of detail, then surely a yellow-red-red pattern as well as a blue-blue-yellow pattern also belong to the way things are in Fido’s world within the period from t 1 to t 3. Once each of the three different temporal arrangements is given due consideration, then, the comprehensive picture of Fido’s world would look like Fig. 6.

The initial motivation behind replacing Fig. 3 with Fig. 4 was to make room for tensed facts involving Fido anchored at times other than the one at which those represented by Fig. 3 are anchored. By interpreting the three columns in Fig. 4 in terms of the picture shown in Fig. 5, however, the standard realist once again imposes her unique locus of obtainment onto the facts represented in the former picture, turning them into ones that are anchored at t 2, and thereby effectively nullifies what promised to make Fig. 4 comprehensive. The blurred brown image of Fido in the middle of the column to the left in Fig. 4, for instance, was meant to represent the future-directed fact that Fido will be brown that is anchored at an earlier time than the time at which the facts represented by the images in the other two columns in Fig. 4 are anchored. The counterpart of this image in the middle of the blue-framed column in Fig. 5 represents, by contrast, the past-directed fact that it was the case that it will be the case that Fido is brown; but this more complex tensed fact is still one that is anchored at t 2, just like any other fact represented in that picture. Positing such further facts anchored at t 2 yet directed at other times in whatever complex ways offers no remedy against the threat of incomprehensiveness, however. In order to cover Fido’s adventures in its full entirety, one needs to do proper justice to the multi-anchoredness of the non-instantaneous tensed reality in Fido’s world. Complicating the present reality may have its uses but making the tensed story genuinely comprehensive is not one of them.

6 Begging the question?

The discussion in the previous section crystallises the difficulty that confronts standard realism: given that a non-instantaneous tensed world is multi-anchored, constituted by facts anchored at multiple times, a mono-anchored representation of it will inevitably leave out some of the ways things are in the relevant world and hence will fail to be comprehensive. But now that it is put this way, the argument might appear to simply beg the question against the standard realist. More precisely, charging the standard realist with ignoring the tensed facts anchored at loci of obtainment other than the only one she is committed to acknowledge might seem dialectically inappropriate, considering that it is a core component of her view that reality features a single unique locus of obtainment. After all, in renouncing neutrality, the standard realist seems precisely to reject that a world like Fido’s is multi-anchored. She might therefore simply insist that, since t 2 is uniquely present and there are no other loci of obtainment but the present, nothing is missing from Fig. 3 (or Fig. 5, for that matter): Fido’s world is to be represented by means of a mono-anchored picture because it is mono-anchored. Moreover, the idea that reality is multi-anchored might appear to be closely connected to the robust conception of temporal passage, which the standard realist eschews, as we have seen above. Given this, the fact that the argument from comprehensiveness appeals to multi-anchoredness might seem to make it doubtful that it is really distinct from Fine’s argument from passage or that it has any advantage over the latter.Footnote 13

Given the delicate nature of the present dialectic, this might appear a reasonable worry, but ultimately, it proves ill-founded. The standard realist, in essence, faces a dilemma: despite appearances, dismissing the multi-anchoredness of a non-instantaneous tensed world does not in fact sit well with standard realism; if, on the other hand, the standard realist does take that path nonetheless, the plausibility of her defence against the argument from passage is seriously undermined.

6.1 Multi-Anchoredness in theory and practice

The rejection of neutrality, combined with the simultaneous acceptance of absolutism, does indeed appear to rule out that reality can be multi-anchored. But while this is the doctrine that the standard realist officially espouses, her overall representational practice deviates from it quite dramatically. Note, for instance, that, in the passage quoted above, Cameron has us first suppose that we are at the second moment of this three-moment history, before he goes on to introduce his single-rowed diagram. That diagram, then, shows us how he represents the tensed reality of this scenario at t 2. Had he represented it at t 1 or t 3, he would have surely drawn the bottom and the top rows of the three-rowed diagram above, respectively. Similarly, we have introduced Fig. 3 above by first assuming that we are looking at Fido’s world when t 2 is the standard realist’s unique locus of obtainment. Had we let the standard realist draw a picture of reality a moment earlier or later, the pictures she would have drawn in each case would look differently, featuring different tensed facts: in the former case, the standard realist would have drawn the column to the left in Fig. 4, and in the latter case, the column to the right. Thus, the standard realist, whenever she claims to tell Fido’s story in its full entirety, ends up disregarding two-thirds of the whole tensed story, though each time a different one.

Focusing on what the standard realist says, at a single time t, about how reality is over some period of time that includes t seems therefore to be rather misleading. For, as has been noted by many, the standard realist’s representational practice involves constant updating—a perpetual discarding of a just drawn picture of reality and immediately drawing a new one from scratch. Thus, if we observe the standard realist over the period from t 1 to t 3 as she continuously represents Fido’s world ‘in real time’, we shall witness that, by the end of that period, she will have drawn each of the columns in Fig. 4. In theory, the standard realist is supposed to hold that reality is, absolutely speaking, mono-anchored; however, her commitment to multi-anchoredness seems to surface in her representational practice.

Note that, apart from the conflict with the standard realist’s official doctrine, there is nothing wrong with this representational practice per se. What is problematic is the claim that mono-anchored pictures like Fig. 3 are both absolute in character and comprehensive in scope: for given that there are multiple distinct ways how things fundamentally are in Fido’s world, each constituted by various facts anchored at a different time, all of these must somehow figure in a diachronically comprehensive representation of Fido’s adventures, as dc and dcs require. Contrast the standard realist’s interpretation of pictures like Fig. 3 with the non-standard realist’s attitude towards them. Non-standard realists will regard each of the columns in Fig. 4 as expressing something true about Fido’s world, but they will deny that any of them reveals either the absolute or the whole truth about it, depending on the type of non-standard realism they defend. Finean fragmentalists, just like B-theorists, will comply with dc and dcs by positing a single picture which is supposed to represent how reality fundamentally is within the period from t 1 to t 3. Whereas that single picture is coherent but tenseless for B-theorists, the fragmentalist’s multi-anchored picture will be tensed but incoherent: the fragmentalist will incorporate the three columns in Fig. 4 by taking them to be proper parts of the fundamentally incoherent reality as a whole. A mono-anchored representation like Fig. 3, then, is absolute in character but partial in scope for the fragmentalist.

By contrast, Finean external relativists will take each of the three columns in Fig. 4 to represent a different, temporally relative reality. On this view, each column reveals a fundamental but temporally perspectival way reality is within the relevant period of time; the tensed story of Fido’s adventures, in its full entirety, involves three distinct temporal perspectives which resist being integrated into a single, ultimate way how things are in Fido’s world. Note that, once absolutism is given up, the other Finean principles as well as the idea of multi-anchoredness takes on a different meaning.Footnote 14 Thus, the external relativist is in fact in a position to accommodate, to some degree at least, whatever intuitive appeal the rejection of neutrality has: for each of the temporal perspectives will be oriented around a locus of obtainment that is, from within that perspective, uniquely privileged. A mono-anchored representation like Fig. 3 will be understood to say everything there is to say about reality, as of the relevant time—this kind of picture is relative in character but (relatively) comprehensive in scope. For the external relativist, there is no single multi-anchored picture of reality; rather, the multi-anchored nature of a non-instantaneous tensed world reveals itself in there being a plurality of temporally relative ways how things fundamentally are.

Consider now a third view, which we may call substandard realism. As far as the Finean principles are concerned, the substandard realist has the same commitments as the standard realist, but she behaves differently in practice. When she continuously represents Fido’s world over the period from t 1 to t 3, she consistently draws the same picture shown in Fig. 3; for the substandard realist, the fundamental tensed reality in Fido’s world is, absolutely speaking, multi-directional but mono-anchored. The multi-directional but mono-anchored picture in Fig. 3 would then really tell us everything we need know about how things are in Fido’s world, and there would be no need to draw any other picture at all.

But despite its similarity to substandard realism on paper, this is not how standard realism is supposed to work. On standard realism, a non-instantaneous tensed world is supposed to be something that constantly changes as a whole and whose fundamental representation therefore constantly requires a total revision that replaces facts that are anchored at a given time with ones that are anchored at the next. But this conception of tensed reality does not seem compatible with the idea that reality is, absolutely speaking, mono-anchored. As soon as one sees how the standard realist produces, over time, a plurality of mono-anchored pictures like Fig. 3, each privileging a different time as the unique locus of obtainment, it becomes clear that she must somehow allow that there is more to a non-instantaneous tensed world, in its full entirety, than what any one of her mono-anchored pictures depict. Intuitively, each of those pictures represents a state from or into which reality transitions within the relevant period; and as we have seen above, a comprehensive account of how this changing tensed reality is within the relevant period needs to involve, in some way and form, all of those states. The non-standard views offer two ways of accomplishing this: take those states as parts of the single fundamental way reality is from to t 1 to t 3, or insist that they constitute multiple, non-integrable fundamental ways reality is within that period. The standard realist does neither and refuses to acknowledge, in any one of her representations of reality, the multi-anchoredness she seems de facto committed to, which is precisely the reason why her view becomes the target of the argument from comprehensiveness.

6.2 Thinning passage further down

The representational practice that accompanies standard realism brings to light that dismissing the multi-anchoredness of a non-instantaneous tensed world is not a straightforward option for the proponent of this view. It might be objected that the above line of argument, in associating the standard realist’s representational practice with multi-anchoredness, tacitly presupposes something like the robust conception of passage that the standard realist rejects. Indeed, one might think that the standard realist’s thin conception of passage both adequately explains her representational practice and is compatible with a non-instantaneous tensed world’s being mono-anchored: the standard realist constantly renews her mono-anchored picture because time passes in the thin sense, without this involving any commitment to reality’s having multiple temporal anchors.Footnote 15

Unfortunately for the standard realist, this kind of response provides little relief either. It is true that the robust notion of passage seems to presuppose multi-anchoredness, but the argument from comprehensiveness appeals only to the latter and not to the former—indeed, for all the argument shows, a multi-anchored tensed world may still be one in which time does not pass. On the other hand, it is in fact very doubtful that, once the multi-anchoredness of a non-instantaneous tensed world is rejected, the thin conception of passage, or whatever is left from it, can be utilised to justify the standard realist’s representational practice or to respond to Fine’s argument from passage.

To see this, let us first distinguish between two theses one might have in mind when one talks of a thin conception of passage:

representationally thin passage (rtp)

A mono-anchored representation can accurately represent a non-instantaneous tensed world in which time passes.

metaphysically thin passage (mtp)

A non-instantaneous tensed world that is mono-anchored can be one in which time passes.

Recall the way in which the thin conception of passage was appealed to in responses to Fine’s argument discussed above: when, for instance, Pooley says, in effect, that a mono-anchored but multi-directed representation is all that is required “to express the passage of time”, he might well be understood as defending rtp rather than mtp. Or take our initial characterisation of the thin conception of passage: we have said that, according to it, there is nothing more to passage than reality’s presently being a certain way and its having been some other way. This, too, is in fact ambiguous between two readings: it may be understood either as a conception of passage that entails rtp only or one that entails mtp as well.

It seems to me that the standard realist’s appeal to the thin conception of passage both in response to the argument from passage and in her attempt to harmonise her representational practice with her rejection of multi-anchoredness of reality trades on the ambiguity between rtp and mtp: what makes the thin conception of passage seem at all acceptable is the former reading, but what the standard realist needs in both dialectical contexts is the latter. Note that mtp is stronger than rtp: the former entails the latter, but not vice versa. It may be that a mono-anchored but multi-directed picture is all that is needed to vindicate the thesis that time passes. But from this, it does not follow that time can pass in a genuinely, absolutely mono-anchored world. Indeed, one might wish to argue that a mono-anchored but multi-directed representation like Fig. 3 manages to capture temporal passage precisely because its multi-directedness signals that there is more to reality than what is represented by it: facts that are anchored at times other than the single one at which the represented facts are all anchored at. On this view, then, a mono-anchored but multi-directed representation accommodates passage to the extent that it implies the multi-anchoredness of the world it represents. But given this, it simply follows that such a representation cannot be absolutely comprehensive: if multi-directedness of a tensed world necessitates some form of multi-anchoredness, then there is more to reality than a multi-directed but mono-anchored representation can possibly represent.

But rtp may also be true simply because mtp is: if time genuinely passes in a mono-anchored tensed world, it is no surprise that a mono-anchored representation can capture temporal passage. However, this option raises a number of difficult questions for the standard realist. If what is meant by the thin conception of passage is something along the lines of mtp, then it allows for temporal passage in substandard realism as well. This, in and of itself, is bad news for the standard realist. For, despite the aforementioned elusiveness of the notion, it seems overwhelmingly plausible that no acceptable conception of passage can allow that a theory which is committed to the substandard realist’s representational practice succeeds in accommodating passage: a non-instantaneous tensed world that is accurately represented, at any time whatsoever, by means of a single mono-anchored picture must indeed be a ‘frozen’ one. Thus, if the standard realist were simply to bite the bullet and adopt the representational practice of the substandard realist, she would certainly bypass the argument from comprehensive but only at the cost of admitting defeat to the argument from passage. After all, as Lipman (2018, p. 97) observes, “[t]he closest that a standard A-theory comes to capturing the passage of time is in the constant rewriting of its description of the world.” One could perhaps argue that compatibility with substandard realism does not, by itself, disqualify a conception of passage. But if the sense in which time can be said to pass in standard realism is one in which it can also be said to pass in substandard realism, then we definitely have far less reason to take the standard realist’s response to the argument from passage seriously, to say the very least.

Alternatively, the standard realist might concede that a theory which is committed to the substandard realist’s representational practice is indeed precluded from accommodating passage but then argue that there is something wrong with that representational practice itself. More specifically, the standard realist might claim that the substandard realist’s representational practice, as described so far, is internally incoherent: if, on the one hand, reality can be accurately represented by the same mono-anchored picture at any time whatsoever, then that picture cannot be multi-directed like Fig. 3; if, on the other hand, we hold the multi-directedness of an accurate picture of reality fixed, then it cannot be that the same picture constitutes, over time, the only single accurate representation of reality. Thus, on this line of thought, what both justifies the standard realist’s representational practice and gives some substance to her thin conception of passage is the multi-directedness of a non-instantaneous tensed world.

It is difficult to see, however, how this response is supposed to work. Take the multi-directed but mono-anchored Fig. 3, featuring past-, present-, and future-directed facts all of which are anchored at t 2. Why exactly is it supposed to be incoherent to always represent reality with this picture and this picture only? Here is one possible reason: the obtaining of past- and future-directed facts represented by it somehow necessitates present-directed facts anchored at times earlier and later than t 2. But, as we have already seen above, if something like this is accepted, it must also be admitted that reality is multi-anchored and that a picture like Fig. 3 is not absolutely comprehensive. If, on the other hand, multi-directedness is completely independent of multi-anchoredness, what is supposed to be wrong with the substandard realist’s practice? If anything, the way in which the substandard realist represents Fido’s world seems be much more fitting than the standard realist’s representational practice, assuming that both are committed to interpreting that world as an absolutely mono-anchored yet primitively multi-directed one. Substandard realism does seem to make a travesty of the way most A-theorists envision reality to be; unlike standard realism, however, it at least does not involve any problematic discrepancy between theory and practice.

In short, appealing to a thin conception of passage does not offer a clear way out to the standard realist: the relevant conception of passage is either robust enough to justify her representational practice, in which case it is incompatible with genuine absolute mono-anchoredness, or it is thinned down to such an extent that it can no longer be plausibly employed to respond to the argument from passage or to make sense of the standard realist’s representational practice.

7 Conclusions

The argument from passage takes as its point of departure the idea that temporal passage consists in, as Price (2011, p. 279) formulates, “a relation between equals, a passing of the baton between one state of affairs and another”, which spells trouble for standard realism because “in this picture, we’ve lost one party to the transaction.” It is the standard realist’s inability to make room for, in Fine’s (2005, p. 288) words, “all the relevant nows” that precludes her from accounting for temporal passage in a satisfactory manner. As we have seen above, standard realists (or those arguing on their behalf) have responded by rejecting the idea that more than one single “party”, more than one single “now”, is relevant for passage—on their preferred alternative conception, passage is much easier to accommodate. But relevant for passage or not, the multi-anchoredness of reality, a plurality of loci of obtainment and facts that are anchored at them, seems to be something that the standard realist is already committed to. For there is no plausible explanation of her representational practice that does not appeal to some form of multi-anchoredness; and if the standard realist were to revise her representational practice in order to bring it into line with a genuinely mono-anchored conception of reality, her claim of accommodating the passage of time would lose any credibility it has.

Thus, we may readily grant the standard realist that any of the mono-anchored pictures she successively draws captures the passage of time, but still insist that each of them manages to depict only a fraction of the total tensed way things are and therefore massively underrepresents reality as a whole. This, by itself, suffices to show the inadequacy of standard realism as a form of realism about tense, but note that it also means that the view tries to escape the McTaggartian argument only by refusing to give a comprehensive account of tensed reality in its full entirety. Given that the standard realist’s mono-anchored pictures ignore all the facts constituting reality save for the ones anchored at one single time, it is unsurprising that they do not contain any potential contradictions which the McTaggartian argument seeks to derive. But this does not really answer the challenge that the argument poses, which, after all, invites one to make proper sense of a multi-anchored reality.

Notes

See also the shorter version of the paper in Fine (2006).

Fine’s discussion is cast in a particular metametaphysical framework he delineates in Fine (2001; 2005, pp. 267–270), the details of which do not concern us here. But note that, although Fine liberally employs talk of facts constituting reality, he (2005, p. 268) is careful to emphasise that this is mainly for convenience and need not imply a reification of facts. On the official Finean view, claims about fundamental reality are to be regimented in terms of a primitive sentential operator, ℜ, such that [ℜ(φ)] is read as [In reality, it is the case that φ]. Here I will simply stick to talk of facts constituting reality.

Since these theses are not perfectly transparent, they lead to several complications upon reflection. I raise one such issue below, but for more on further interpretive challenges, see Loss (2017). Other critical discussions of Fine’s McTaggartian argument include Correia & Rosenkranz (2012); Deng (2013); Tallant (2013); Cameron (2015, pp. 86–93); Savitt (2016); Loss (2018); and Eker (2021).

Fine (2005, p. 299) seems to acknowledge this as well when he writes: “[I]n so far as reality comprises tensed facts, it must be oriented towards the present.”

This implies that Fido is a spatially extended mereological simple and lacks any temporal proper parts, but nothing turns on these issues. I also ignore the complication that colour properties might appear rather unlikely candidates for being components of fundamental facts.

This is particularly true in the case of presentism, which is the most widespread type of standard realism. Here I am ignoring any possible complications stemming from different temporal ontologies standard realists may accept.

For discussion of Fine’s argument from passage, see, e.g., Deng (2013); Pooley (2013, pp. 327–330); Tallant (2013, pp. 284–294); Cameron (2015, pp. 93–95); Savitt (2016, pp. 83–87); Deasy (2018); Lipman (2018); and Correia & Rosenkranz (2020). For other recent arguments focusing on passage, see Price (2011, pp. 277–280); and Leininger (2015). Note that Fine’s overall case against standard realism involves two further arguments, the argument from truth and the argument from relativity; for critical discussion, see, e.g., Tallant (2013, pp. 294–304); Cameron (2015, pp. 95–102); Savitt (2016, pp. 88–97); Hofweber & Lange (2017); and Torrengo & Iaquinto (2019).

The last two emphases are mine. Cameron is responding here to Smith (2011).

I am grateful to two anonymous referees for pressing me on these points.

As Fine (2005, p. 271) himself points out.

I thank an anonymous referee for prompting me to say more about this line of defence.

References

Cameron, R. (2015). The Moving Spotlight: An Essay on Time and Ontology. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Correia, F., & Rosenkranz, S. (2012). Eternal Facts in an Ageing Universe. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 90(2), 307–320

Correia, F., & Rosenkranz, S. (2020). Unfreezing the Spotlight: Tense Realism and Temporal Passage. Analysis, 80(1), 21–30

Deasy, D. (2018). Philosophical Arguments against the A-Theory. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 99(2), 270–292

Deng, N. (2013). Fine’s McTaggart, Temporal Passage, and the A versus B-Debate. Ratio, 26(1), 19–34

Eker, B. (2021). Dynamic Absolutism and Qualitative Change. Philosophical Studies, 178(1), 281–291

Fine, K. (2001). The Question of Realism. Philosophers’ Imprint, 1(1), 1–30

Fine, K. (2005). Tense and Reality. Modality and Tense (pp. 261–320). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Fine, K. (2006). The Reality of Tense. Synthese, 150(3), 399–414

Hofweber, T., & Lange, M. (2017). Fine’s Fragmentalist Interpretation of Special Relativity. Noûs 51(4), 871–883

Leininger, L. (2015). Presentism and the Myth of Passage. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 93(4), 724–739

Lipman, M. (2015). On Fine’s Fragmentalism. Philosophical Studies, 172(12), 3119–3133

Lipman, M. (2018). A Passage Theory of Time. In Karen Bennett and Dean W. Zimmerman (Eds.), Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, vol. 11 (pp. 95–122). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Loss, R. (2017). Fine’s McTaggart: Reloaded. Manuscrito, 40(1), 209–239

Loss, R. (2018). Fine’s trilemma and the reality of tensed facts. Thought, 7(3), 209–217

McTaggart, J. M. E. (1908).The Unreality of Time. Mind, 17(68), 457–474

Pooley, O. (2013). Relativity, the Open Future, and the Passage of Time. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 113(3), 321–363

Price, H. (2011). The Flow of Time. In C. Callender (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Time (pp. 276–311). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Prior, A. N. (2003). Changes in Events and Changes in Things. In Per Hasle, Peter Øhrstrøm, Torben Braüner, and Jack Copeland (Eds.), Papers on Time and Tense, new edition (pp. 7–19). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Savitt, S. (2016). Kit Fine on Tense and Reality. Manuscrito, 39(4), 75–99

Simon, J. (2018). Fragmenting the Wave Function. In Karen Bennett and Dean W. Zimmerman (Eds.), Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, vol. 11 (pp. 123–145). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Skow, B. (2015). Objective Becoming. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Smith, N. J. J. (2011). Inconsistency in the A-Theory. Philosophical Studies, 156(2), 231–247

Solomyak, O. (2013). Actuality and the Amodal Perspective. Philosophical Studies, 164(1), 15–40

Tallant, J. (2013). A Heterodox Presentism: Kit Fine’s Theory. In Roberto Ciuni, Kristie Miller, and Giuliano Torrengo (Eds.), New Papers on the Present: Focus on Presentism (pp. 281–305). Munich: Philosophia

Torrengo, G., & Iaquinto, S. (2019). Flow Fragmentalism. Theoria, 85(3), 185–201

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Graduate Colloquium in Theoretical Philosophy at University of Tübingen—many thanks to the audience on that occasion for the helpful discussion. I am especially grateful to Thomas Sattig, Tobias Wilsch, Daniel Deasy, and Gaétan Bovey for their extensive and insightful feedback on earlier drafts of the paper. Finally, I am also indebted to three anonymous referees for this journal for their incisive critical comments and useful suggestions. Research on this paper was generously supported by Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eker, B. The a-theory of time, temporal passage, and comprehensiveness. Synthese 200, 123 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03532-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03532-1