Abstract

I offer a novel account of temporal passage. According to this account, time passes in virtue of there being events in progress. I argue that such an account of temporal passage can explain the direction and whoosh of temporal passage. I also consider two prominent accounts of temporal passage and argue that they amount to special versions of the thesis that time passes in virtue of there being events in progress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In these examples, the progressive aspect is marked by combining the copula with the present participle of a verb. Certain environments, though, do not require the copula: in Mirah saw Willa running, the small-clause Willa running is in the progressive aspect but the copula is absent.

The imperfective paradox owes its name to Dowty (1977).

Just instance \(\varphi \) with the event type willa build a house. There can be a willa build a house event in progress even though it’s not presently a willa build a house event and there never was nor will be such an event. More colloquially, Willa can be building a house even though it is never the case that she builds a house.

One might object that this argument is too quick on the following grounds. Suppose e is presently a \(\varphi \) event in progress. Surely it follows that there is presently an incomplete\(\varphi \) event. So, with this notion of an incomplete event, why can’t the A-theorist say that an event is a \(\varphi \) in progress in the present (or past or future) just in case e is an incomplete \(\varphi \) event in the present (or past or future, respectively). In response, the A-theorist could say this but she would be cheating if in saying it she was offering a reductive account of what is for an event to be a \(\varphi \) event in progress. The cheat is that any plausible account of what is for an event e to be an incomplete \(\varphi \) event will involve e being a \(\varphi \) event in progress (before it ends). For similar reasons, appealing to incomplete events won’t help circumvent the next moral.

Resultant states might seem like “ghostly” entities. Maybe they are. But that’s not a serious objection to their existence. In any case, Parsons (1990) was the first to bring resultant states to light. Since then they have been put to a variety of uses in semantics and metaphysics. See Higginbotham (2009), Szabó (2006), and Zimmerman (2011).

Another, more controversial, worry: “What about the possibility of “backward” events in progress? If backward events in progress are possible, then such an event in progress would be directed at an earlier rather than later state-of-affairs and so (D1) would be subject to counterexample.” In response, let me say two things. First, if the literature on time travel and backward causation is to be a guide, arguments for the possibility of backward events in progress will be highly contentious. Of course, this is no argument against the possibility. But it does bring out an important dialectical point. My aim, recall, is just to put In-Progress on the list of temporal passage theses taken seriously. Controversy surrounding the consistency of a thesis with the possibility of backward phenomenon (e.g., time travel to the past and/or backward causation) does not prevent a thesis from being on the list. Thus, for the purposes of this paper, worries about the possibility of backwards events in progress can be set aside, whether the worries are about a motivation for the thesis or the thesis itself. Second, neither time travel to the past nor backward causation (if possible) entail backward events in progress. Consider the following scenario from Wasserman (2015).

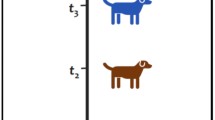

Suppose that a single electron persists from \(t_1\) to \(t_3\), at which point it finds its way into an experimental time machine. At that moment, a scientist presses a button and the electron is sent back, discontinuously, to \(t_2\) where it goes on to live a long and happy life.

Granting the supposition, while the electron traveled back in time (from \(t_3\) to \(t_2\)), it doesn’t seem to be the case that the electron was, at any time from \(t_1\) to \(t_3\), traveling back in time. It just found itself back at \(t_2\). Likewise, while the push of the button at \(t_3\) caused the electron to be “back” at \(t_2\), it doesn’t seem to be the case that the push of the button was, at \(t_3\), causing the electron to be “back” at \(t_2\). (The more general point is that there being a \(\varphi \) event doesn’t entail there being a \(\varphi \) event in progress. To arrive at destination need not be proceeded by an event in progress of arriving at that destination. To recognize a face need not be proceeded by an event in progress of recognizing a face.) Thus, to argue for the possibility of backward events in progress, one is going to have to do more than argue for the possibility of time travel to the past or the possibility of backward causation.

I don’t have an account of what it is for something to have a dynamic character. If pressed, I could say that dynamic character is related to change. But I would rather take dynamic character as a primitive.

To see one motivation for this fine-grained account of the directedness of an event in progress, go back to the expanding universe example. Take any (non-initial or non-final) moment t in a (sufficiently extended) interval over which there is an event in progress of the universe expanding. At t, the event in progress brings about a state of the universe having expanded. However, the event in progress isn’t over at t; it remains an event in progress of the universe expanding. Thus, we can’t simply have the event in progress be directed, at t, at bringing about a state of the universe having expanded. It already has brought about many such states and brings about such a state at t. So, it seems that we need a more fine grained account of what the event in progress is directed at (at t) to capture the “in progress” nature of the event in progress at t. (D1) satisfies this need.

The constant update of events in progress also offers an an account of the rate of temporal passage: time would pass at the rate of x moments of time per x updates of an event in progress. Thus, another source of motivation for In-Progress is that offers an account of the rate of temporal passage. There is, however, considerable debate about whether it makes sense to ascribe a rate to temporal passage. See Skow (2011) for an overview of the controversy.

See Deng (2013) for a more careful version of the argument that follows.

Markosian (1993) offers such an understanding the successive possession of A-properties. Witness:

I will refer to the process by which times and events successively possess different A-properties as the pure passage of time, and I will refer to the thesis that there is such a process as the pure passage of time thesis. (p. 835)

These last two observations are for those A-theorists who favor moving spotlight or growing block theories of passage.

Skow (2015) is one of many great works on passage that ignore aspect. Skow does, however, at least footnote that aspect is an important way in which English encodes temporal information (Chapter 2, footnote 4). Sadly, he goes on to say that he will ignore this “complication.” This is especially sad given that when he discusses Russellian change, the progressive is all over the place. Witness:

Russell’s theory of change starts with what looks like a platitude about change:

- (2.)

Something is changing if and only if (i) it is currently one way, and (ii) it was (not long ago) some other, incompatible way. (p. 23)

But if we take the progressive marking seriously, (2) is far from a platitude. It is an obvious falsehood.

- (2.)

McTaggart (1908) provides the first and most famous incoherence argument.

See Zimmerman (2011) for an lengthy discussion of presentism, a special version of A-theory, and our best physical theories.

Objection: “Our best physical theories tell us that the fundamental laws of nature are time reversal invariant. Perhaps, then, our best physical theories don’t really tell us the electrons attract protons, since in a time reversed world, it would seem that electrons repel protons even though the laws would still apply.”

The scope of this paper permits only a brief response. Suppose the fundamental laws are time reversal invariant. Further suppose that it follows from this that the fundamental laws don’t entail that electrons attract protons. Nothing in our assumptions so far entails that the fundamental laws entail that electrons don’t attract protons. So, we don’t yet have an argument that events in progress are inconsistent with our best physical theories, which is the suppressed conclusion of the objection. Of course, a rigorous defense of In-Progress would require one to say more about how the thesis accords with our best physical theories. But my aim is not to provide such a defense of the thesis.

Some further clarification may be in order. Suppose a chunk of salt is placed in water but taken out before it is fully dissolved. There is thus a partial manifestation of the salt’s disposition to dissolve in water. Kroll’s claim with respect to this case is that there corresponds an event disposed to become one in which the salt is dissolved. This disposition was activated and so there was a partial manifestation of the disposition of the event. This partial manifestation was the event in progress of the salt dissolving.

References

Deng, N. (2013). Fine’s Mctaggart, temporal passage, and the A versus B-debate. Ratio, 26(1), 19–34.

Dowty, D. R. (1977). Toward a semantic analysis of verb aspect and the English imperfective progressive. Linguistics and Philosophy, 1(1), 45–77.

Dowty, D. R. (1979). Word meaning and Montague grammar: The semantics of verbs and times in generative semantics and in Montague’s PTQ. Boston, MA: Kluwer.

Fine, K. (2006). The reality of tense. Synthese, 150(3), 399–414.

Higginbotham, J. (2009). Tense, aspect, and indexicality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kroll, N. (2015). Progressive teleology. Philosophical Studies, 172(11), 2931–2954.

Kroll, N. (forthcoming). Fully realizing partial realization. Glossa.

Landman, F. (1992). The progressive. Natural Language Semantics, 1(1), 1–32.

Leininger, L. (2013). On Mellor and the future direction of time. Analysis, 148–157.

Markosian, N. (1993). How fast does time pass? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 53(4), 829–844.

McTaggart, J. E. (1908). The unreality of time. Mind, 17(68), 457–474.

Mozersky, M. J. (2015). Time, language, and ontology: The world from the B-theoretic perspective (Vol. 3). Oxford: OUP.

Oaklander, N. (2012). A-, B-, and R-theories of time. In A. Bardon (Ed.), The future of the philosophy of time (pp. 1–24). New York, NY: Routledge.

Parsons, T. (1990). Events in the semantics of English. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Paul, L. A. (2010). Temporal experience. The Journal of Philosophy, 107(7), 333–359.

Portner, P. (1998). The progressive in modal semantics. Language, 74(4), 760–787.

Price, H. (1997). Time’s arrow and Archimedes’ point: New directions for the physics of time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Prior, A. N. (1962). Changes in events and changes in things. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas, Department of Philosophy.

Skow, B. (2011). On the meaning of the question: How fast does time pass? Philosophical Studies, 155(3), 325–344.

Skow, B. (2015). Objective becoming. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smart, J. J. (1949). The river of time. Mind, 58(232), 483–494.

Szabó, Z. G. (2004). On the progressive and the perfective. Noûs, 38(1), 29–59.

Szabó, Z. G. (2006). Counting across times. Philosophical Perspectives, 20(1), 399–426.

Szabó, Z. G. (2008). Things in progress. Philosophical Perspectives, 22(1), 499–525.

Wasserman, R. (2015). Lewis on backward causation. Thought: A. Journal of Philosophy, 4(3), 141–150.

Williams, D. C. (1951). The myth of passage. The Journal of Philosophy, 48(15), 457–472.

Zimmerman, D. (2011). Presentism and the space-time manifold. In C. Callender (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of philosophy of time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank two anonymous reviewers for comments and criticism that greatly improved this paper. I’d also like to thank Natalja Deng for helpful comments on an early version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kroll, N. Passing Time. Erkenn 85, 255–268 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-018-0026-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-018-0026-4