Abstract

The reaction of 1-phenyl-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazolino-3,5-dione (4) with 3-molar excess ethylene oxide was described. The resulting product was characterized by spectroscopic techniques (1H-, 13C-NMR, IR, and UV) and by X-ray crystallography. It was expected to produce a product of the subsequent reaction in the hydroxyl groups of the initially formed diol—1-phenyl-2,6-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dione (7) with ethylene oxide (5). However, crystallographic studies revealed that the proper and only product of the reaction is 3-{2-[1,3-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-oxo-4-phenylimidazolidin-5-yl]phenyl}-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one (8). This product was formed by quinazoline ring opening which occurred in the presence of more than 2-molar excess ethylene oxide. In the work, the exemplary reaction mechanism explaining the formation of the unexpected product was proposed. In order to understand the reasons of quinazoline ring opening, the quantum mechanical modeling was performed. Energy of transition states indicated that the reaction with the third mole of ethylene oxide was controlled by kinetics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

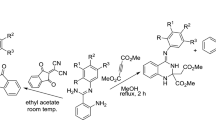

During the reaction of 3-amino-3R-1H-quinoline-2,4-diones (1) with urea at the boiling point of acetic acid, 1R-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-diones (2) were produced instead of the expected 3a-R-3H,5H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinoline-2,4-diones (3), (Fig. 1) [1].

1-R-2H,6H-Imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-diones were formed by intramolecular rearrangement as described in details in [2]. A similar situation took place during the reaction of 1-substituted or 1,1-disubstituted urea with 3-amino-3-R-1H-quinoline-2,4-diones [3]. Then, the substituent in the urea molecule was disconnected, and 1-R-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]-quinazoline-3,5-diones (2) were formed just as during the reaction with urea.

When nitrourea was applied, 1-R-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-diones (2) and 9b-hydroxy-3-R-3a,5,9b-tetrahydro-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinoline-2,4-diones were formed depending on the solvent type [3].

If 3-amino-1-R’-3-R-quinoline-2,4-diones—comprising tertiary lactam group—took part in the reaction, three different products were obtained [2]. An intramolecular rearrangement also took place during the reaction but this time from quinolone to indolinone system and 3-(3-acylureido)-2,3-dihydro-1-R’-indol-2-ones or 4-alkylidene-10H-spiro[imidazolidine-5,30-indol]-2,20-diones were formed. The typical product—3a-R-3H,5H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinoline-2,4-dione—was also made [2].

Reaction of 3-amino-3-phenylquinoline-1H,3H-2,4-dione (1, R = Ph) with urea resulted in the production of 1-phenyl-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dione (2, where R = Ph, i.e., 4) in a yield of approx. 84 wt%.

The compound (4) could be reacted with ethylene oxide (EO, 5), and then, alcohol (6) [4] and diol (7) [5] with the imidazoquinazoline rings were successively produced according to the scheme shown in Fig. 2.

Compounds containing imidazoquinoline and imidazoquinazoline rings have interesting properties. Quinazoline derivatives have a wide spectrum of biological properties, which allow their use in the production of anti-inflammatory [6], anti-parasitic [7], anti-histamine [8], anti-diuretic [9], and anti-cancer [10] drugs. In turn, imidazoquinazoline derivatives have wide application in medicine and pharmacy due to their anti-tumor, anti-viral, anti-bacterial or anti-convulsive, and anti-oxidative activity [11,12,13,14,15,16].

Compounds that contain in their structure a ring of imidazole, imidazolone, or oxazole also show biological activity, e.g., imidazole derivatives with alkyl phenyl substituents described in [17] are used in the treatment of mental disorders, i.e., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and autism spectrum disorder. Imidazole derivatives with aryl or heteroaryl substituents are used in the prevention and treatment of cancer as well as in the treatment of RAF kinase–mediated disorders [18]. 4,5-Disubstituted imidazole derivatives are used as anti-inflammatories and cytokine inhibitors in the treatment of p38/MAP kinase–mediated disorders [19]. Imidazolone derivatives are used to modify biological signaling processes and as reagents in biological tests [20]. The compounds with the imidazole and oxazole moieties are also used in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders [21].

In this work, we have studied the reaction product of (4) with 3-molar excess of EO. It resulted in a completely unexpected reaction course, during which the quinazoline ring was opened and 3-{2-[1,3-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-oxo-4-phenylimidazolidin-5-yl]phenyl}-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one (8) was formed as shown in Fig. 3.

The resulting product (8) was characterized by means of instrumental methods. The structure of the product was unambiguously confirmed by single-crystal X-ray crystallography. The product can also have biological activity.

Quantum mechanical calculations can explain the reasons of the unexpected reaction course. An exemplary mechanism of the reaction product formation of (4) with 3-molar excess of EO was proposed. The possible mechanism was also confirmed by quantum mechanical modeling.

Results and discussion

Predicted reaction course of 1-phenyl-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dione with 3-molar excess of ethylene oxide

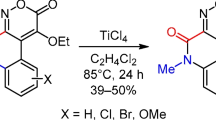

The compound (4) due to its high melting point (> 400 °C) could be used as a starting material for the synthesis of thermally stable polymers [22, 23]. However, this compound was insoluble in water and common organic solvents. Therefore, it was necessary to obtain its more soluble derivatives. This was why the hydroxyalkylation reactions were carried out using an excess of EO. The reactions were catalyzed with triethylamine (TEA) and maintained at 70–80 °C. An alcohol (6) and diol (7) with imidazoquinazoline ring were obtained with an equimolar amount of EO or 2-molar excess of EO as described in “Introduction” [4, 5]. It was expected to produce etherols (9–11) with the imidazoquinazoline ring in the reaction of (4) with 3-molarexcess of EO, under conditions analogous to the synthesis of (6) and (7). The synthesis scheme was given in Fig. 4.

Yellow crystals were obtained as the only product in a yield of 74 wt%. The melting point of this compound was 162–163 °C.

Results of elemental analysis confirmed composition of the product. The calculated element shares are consistent with the experimental ones (see Experimental Part).

The electrospray ionization mass spectrum (Fig. 1S) of the product studied showed the protonated molecules [M + H]+ as the only ions in the spectrum, which confirms unambiguously the expected molecular weight.

Compound was also analyzed using electron impact ionization mass spectrometry (EI-MS). Contrary to the ESI-MS experiments, the direct loss of one or two water molecules is the typical fragmentation pathway observed in the EI-MS (Fig. 2S).

A preliminary spectral analysis suggested that the derivative (10) was obtained. All signals in the 1H-and 13C-NMR spectra were assigned to the corresponding atoms on the basis of COSY, NOESY, HSQC, and HMBC experiments (Figs. 3S–7S), and their positions were in agreement with the proposed structure.

The 1H-NMR spectrum of the product was shown in Fig. 5, in which the proton signals of two hydroxyl groups at a chemical shift of 4.8 ppm were observed.

Furthermore, additional signals appeared above 4 ppm, compared to the spectrum of the diol (7) (Fig. 8S). There were two doublets of triplets at 4.05 and 4.25 ppm, whereas just one triplet was observed at 4.1 ppm in the diol (7) spectrum (Fig. 8S). These signals were derived from the enantiotopic protons of the methylene group linked to the nitrogen atom no. 6 of (10). The protons of the next methylene group behaved similar. The difference of their chemical shift was higher than 1 ppm. They appeared at 3.68 and 2.65 ppm. Methylene protons of the hydroxyethyl group combined with an ethoxy group at the nitrogen atom no. 6 existed in the form of two triplets at 3.45 and 3.58 ppm for –O–CH2 and –CH2OH, respectively. The signals of the methylene protons of the 2-hydroxyethyl group at the nitrogen atom no. 2 were in the form of two triplets at 3.62 and 3.72 ppm for –N–CH2 and –CH2OH, respectively.

13C-NMR spectrum of the obtained derivative has been presented in Fig. 6. There were six signals in the range from 43 to 62 ppm of carbon atoms with sp3 hybridization. They corresponded to the carbon atoms of three ethylene groups.

Signals of carbonyl groups were present at 155.27 and 153.21 ppm. They were shifted to higher values of δ compared to the spectrum of the starting compound (4) and alcohol (6) or diol (7) with imidazoquinazoline ring. There, they were observed at 147.96 and 144.8 ppm (Fig. 8S).

Signals in the range of 115–140 ppm originated from the carbon atoms of the phenyl ring and imidazoquinazoline ring. Their positions were a bit different from the corresponding peaks found in the 13C-NMR spectra of alcohol (6) and diol (7) with imidazoquinazoline ring [4, 5] (Fig. 8S).

Similarly, a comparison of the 1H-NMR spectra of the obtained derivatives, i.e., alcohol (6) and diol (7), showed that the proton signals of the phenyl and imidazoquinazoline rings had slightly different location (Fig. 7S).

The IR spectrum of the product aroused further doubts concerning the presence of the imidazoquinazoline ring in the product structure. It appeared that the bands at 1631, 1587, and 1485 cm−1 in the IR spectrum (Fig. 9S) characteristic for the imidazoquinazoline ring were not observed.

Ultimately, crystallographic studies revealed that the analyzed reaction was not running according to the reaction scheme shown in Fig. 4. The analyzed product was not the product 10. The crystallographic structure of the obtained product indicated that during the reaction, the imidazoquinazoline ring was opening. The reaction ran according to the scheme shown in Fig. 7. In fact, the product (8) was formed.

X-ray crystallography of 3-{2-[1,3-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-oxo-4-phenylimidazolidin-5-yl]phenyl}-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one

The identity of (8) was proven by the single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. It turned out that investigated compound crystallizes in monoclinic P21/c space group with one molecule of compound in the asymmetric part of the unit cell (Fig. 8).

The molecular structure of (8) with atomic labels. Displacement ellipsoids were drawn at the 25% probability level, and the H-atoms were shown as small spheres of arbitrary radius. The intramolecular C–H···O hydrogen bonds were represented by the dashed lines, and the C–H···π and C=O···π interactions by the dotted lines. The Cg2 and Cg3 denote the geometric centers of gravity of the rings defined by the C1–C5 and C6–C11 atoms, respectively

The details of crystallographic data and refinement parameters were summarized in Table 1. The values of bond lengths, valency, and torsion angles were gathered in Table 1S.

In the molecule of (8), the mean planes defined by C6–C11 and C19–C25 atoms of the phenyl rings were inclined by the angles of 49.84(4) and 125.91(4)° with respect to the mean plane defined by atoms of the imidazolidinone moiety. The angle between the mean planes defined by the non-hydrogen atoms of the oxazolidinone moiety and the phenyl ring, which was directly linked to this fragment, equaled to 122.66(4)°.

In turn, the mean planes defined by the non-hydrogen atoms of the oxazolidinone moiety and the phenyl ring described by the atoms C6–C11 were inclined to themselves by a relatively small angle (6.23(4)°). These moieties were involved in the intramolecular C–H···π contact (Fig. 8, Table 2S). There were also two weak C–H···O hydrogen bonds formed by 2-hydroxyethyl chains, oxazolidin-2-one moiety, and the phenyl ring defined by the C6–C11 atoms (Fig. 8, Table 2S), as well as the C=O···π contact, the carbonyl oxygen atom of the oxazolidin-2-one fragment, and the imidazole ring (Fig. 8, Table 3S).

Detailed analysis carried out with the PLATON program [24] revealed various types of intermolecular interactions (and in the consequence short contacts shorter than the sum of the van der Waals radii) in the crystal lattice of the studied compound. Such short contacts were listed in Tables 2S and 3S. In the crystal, adjacent molecules of (8) were incorporated in the network the O–H···O hydrogen bonds, which resulted in the formation of infinite chains of the molecules running along the a-direction (Fig. 9a, Table 2S). The abovementioned chains were additionally stabilized by the presence of the weak C–H···π intermolecular contacts (Fig. 9a, Table 2S). The adjacent molecules in the neighboring chains were further interacting by the weak C–H···O and C–H···π intermolecular interactions (Table 2S), and the complex supramolecular framework depicted on Fig. 9b was finally created.

The arrangement of molecules of (8) in the crystal, where a an infinite chain of molecules incorporated in the O–H···O and C–H···O hydrogen bonds running along the a-direction; b a general view on the supramolecular framework created by the molecules of investigated compound viewed along the a-direction (single chain of molecules viewed from the top is highlighted in green). The O–H···O and C–H···O hydrogen bonds are represented by the dashed lines and C–H···π intermolecular interactions by the dotted lines. The H-atoms not participating in intermolecular interactions were omitted for clarity. Symmetry codes: (i) − x + 1, − y + 1, − z + 2; (ii) − x, − y + 1, − z + 2; (iii) x, y, z – 1; (iv) − x + 1, − y + 1, − z + 1; (v) x, − y + 3/2, z − 1/2; (vi) x − 1, y, z

Considering the percentage contribution of various contacts to the Hirshfeld surface (Figs. 10 and 11), it became clear that the largest share was attributed to the presence of the H···H contacts (54.9%), which was common in organic molecular crystals [25]. The existence of hydrogen bonds was manifested by the 25.7% share of the O···H contacts to the Hirshfeld surface (Figs. 10e and 11). Two characteristic spikes on the fingerprint plot associated with the O···H contacts (Fig. 10e) resulted from the presence of the O–H···O hydrogen bonds. The C–H···π interactions had the 17% and 2.1% share of the C···H and the N···H contacts, respectively (Figs. 10f, g and 11). Performed analysis indicated also the presence of the C···O contacts; however, their share was hardly perceptible (only 0.1%) (Figs. 10h and 11).

To better understand the nature of packing of molecules in the crystal of the investigated compound, the Hirshfeld surface analysis using CrystalExplorer program was performed [26]. Examination of two dimensional (de/di) fingerprint plots associated with the Hirshfeld surface (Fig. 10) confirmed the occurrence of intermolecular interactions identified by PLATON [8] (Tables 3S–5S).

Quantum mechanical modeling of 3-{2-[1,3-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-oxo-4-phenylimidazolidin-5-yl]phenyl}-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one

The crystal study of compound (8) showed that only one pair of its conformers (Fig. 12) was formed whereas theoretically, there were 32 pairs of enantiomers possible.

Compound (8) has no chiral atoms but the molecule was asymmetrical. The imidazolidinone ring was flat; the phenyl rings were set at determined angles towards the plane of the imidazolidinone ring. Each phenyl ring could take two limited positions. The oxazolidinone ring also could have two limited positions relative to the phenyl ring. Additionally, the hydroxyethyl groups could be located above or below the imidazolidinone ring plane. Therefore, (8) could theoretically exist in the form of 32 pairs of conformers.

Quantum mechanical calculations for the compound (8) were carried out based on the total energy of the conformers as an optimization criterion and on the assumption that there was no interaction between the conformers. Quantum mechanical calculations revealed that there were 12 pairs of stable conformers of (8). Twelve conformers were illustrated in Fig. 11S. The rest of conformers constituted their mirror reflections.

Next, the percentage shares of all the 24 conformers of (8) were determined based on their values of the Gibbs free energy (enthalpy). The results, which were shown in Table 2, indicated that one pair of conformers (GBGBF and its mirror reflection) constituted 95.58% of all conformers. This was the pair which was found in the crystal. Another pair of the (8) conformers (DBGBF and its mirror reflection) constituted 4%. The total amount of the rest 20 conformers was negligibly small.

The reaction course of 1-phenyl-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dione with 3-molar excess of ethylene oxide

The said reaction of (4) with 3- molar excess of EO can be divided into four stages as shown in Fig. 13.

In the first step, the molecule (4) attacks the EO molecule (5) by the nitrogen atom no. 2 and 1-phenyl-2-(2-hydroxyethyl)-6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dione (6) is formed [4].

In the second step, the molecule of (6) attacks another molecule EO by the nitrogen atom no. 6. It leads to the obtaining of 1-phenyl-2,6-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dione molecule (7) [5].

In the third step, the intramolecular reaction of (7) takes place. Then, the 2-hydroxyethyl group at the sixth position reacts with the carbonyl group at the fifth position. This results in the imidazoquinazoline ring opening to give 3-{2-[1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-oxo-4-phenylimidazolidin-5-yl]phenyl}-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one (12).

In the final step, the compound (12) reacts with the third mole of EO giving 3-{2-[1,3-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-oxo-4-phenylimidazolidin-5-yl]phenyl}-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one (8).

It was tested that the necessary condition for the imidazoquinazoline ring opening was the presence of a higher than 2-M excess of EO. Carrying out the reaction of (4) with two moles of EO in the presence of an increased amount of TEA, an extension of the reaction time or increasing the reaction temperature to 90 °C did not lead to the ring opening.

Explanation of reaction course based on quantum mechanical modeling

In order to clarify the reasons for this unexpected reaction product of (4) with 3-molar excess of EO, quantum mechanical modeling was used.

Initially, the values of the Gibbs free energy of conformers of the expected derivatives (9) and (10) (Fig. 12S) were calculated. The number of the (9) and (10) conformers was determined based on their structures. Quantum mechanical calculation revealed that phenyl ring could only be in two limited positions: inclined to the plane of the imidazoquinazoline ring at an angle smaller or greater than 90° (with the “top” inclined to the left or right as it was shown in Fig. 11S). The value of angle was determined by Gaussian program.

The hydroxyethyl and hydroxyethoxyethyl groups could be attached to one possible position. In each position, those substituents could be above or below the plane of imidazoquinazoline ring—this gives four possibilities. Hydroxyethyl and hydroxyethoxyethyl substituents could rotate with a multiplied number of conformers. Nevertheless, after optimization, the hydroxyethyl and hydroxyethoxyethyl chains became straightened. This resulted in the compact set of eight conformers shown in Fig. 12S.

Next, the Gibbs free energy values for conformers (9) and (10) and conformers of compound (8) resulting from the X-ray diffraction study (Fig. 12) were juxtapositioned in Table 3.

Assuming that both derivatives (10) and (8) were formed and based on the free energy of the individual conformers, the conformer’s shares were calculated (Table 3).

The calculations indicated that the derivative (8) was likely to occur as the energy of the conformers (8) was slightly higher than that of the conformers (9) and (10).

In a next step, the Gibbs free energy conformers of the intermediate product—the diol (7) (Fig. 13S) and 3-{2-[3H-1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-5-oxo-3-phenylimidazolidin-3-yl]phenyl}-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one (12) (Fig. 14S)—were calculated and shown in Table 4.

Energy values were used to determine the shares of the conformers (7) and (12) in the entire population. The energy of the conformer (12) was higher than in the case of the conformers of the diol (7). We observed the total lack of conformers (12). This explained the lack of the derivative (12) in this reaction. The use of the three moles of EO caused the quinazoline ring to open because the derivative (12) of a higher energy (app. − 3,251,300 kJ/mol) than the diol (7) (app. − 3,251,585 kJ/mol) could be reacted with EO to give the product (8) with a lower energy (− 3,655,292 kJ/mol).

However, we still have remembered that derivatives (9) and (10) had lower energy than the compound (8).

Ultimately, the shape of HOMO orbitals of the diol (7) allowed us to understand why hydroxyethyl groups of the diol (7) did not react with oxirane, why quinazoline ring was opened, and why the imidazole ring remained unaffected.

Figures 14 and 15 illustrate the electron density distribution in the diol (7) and EO (5) molecules, respectively. The electron deficit of carbon atom no. 5 of diol (7) was much higher than in the carbon atoms in the EO molecule (Figs. 14 and 15).

This caused the intramolecular substitution in the diol (7) molecule to be easier than the reaction between the diol (7) and EO, despite the lower energy (− 3,656,280 kJ/mol) of the derivative (9) or (10) than compound (8) (− 3,655,292 kJ/mol). Due to the higher energy of the compound (12) than the diol (7), the intramolecular substitution occurred only in the presence of EO. This allowed for further reaction leading to the product (8) of lower energy than the compound (12).

The deficit of the electron density was clearly marked on the carbon atom of the carbonyl group no. 5 as opposed to carbon atom no. 3. Thus, the intramolecular nucleophilic substitution was possible only with the participation of the quinazoline ring (carbonyl group no. 5), instead of the imidazole ring (carbonyl group no. 3) with the formation of the alternative product (14)—DDS1 (Fig. 16).

It should be emphasized that the energy of the product (14) (− 3,252,402 kJ/mol) was lower than the product (12) (− 3,251,300 kJ/mol). It suggested that the product (14) should be formed easier, and consequently, the product (15)—DDSD—too. Energies of the product (15)—DDSD—and (8) were comparable, − 3,655,291.46 kJ/mol and − 3,655,292.11 kJ/mol, respectively.

However, as mentioned earlier, the energies of the final products (8 and 15) and intermediate products (7, 12, and 14) did not determine the reaction course, only HOMO orbitals’ shape of diol (7).

In the next step, Gibbs free energies of transition states of three different alternative reaction paths were computed and compared. Reaction paths were shown schematically in Fig. 17. Comparison of Gibbs free energies of all products and transition states was illustrated in Fig. 18. Precise data of the change of Gibbs free energies were juxtapositioned in Table 5.

The change of Gibbs free energies of transition states during transformation of the diol (7) into the derivative (12) and reaction of the (12) with EO to the diol (8) was 1350.14 and 1361.18 kJ/mol, respectively, whereas the change of Gibbs free energy of reaction (the diol 8) with EO to the (9) or the (10) was 1390.36 and 1384.68 kJ/mol, respectively. Thus, the reaction of intramolecular substitution in the diol (7) molecule forming (12) has been easier than the reaction of hydroxyl group of the diol (7) with EO.

This meant that the reaction of the diol (7) with the third mole of EO was controlled by kinetics. It provided strong support for the proposed mechanism.

Experimental

Materials

1-Phenyl-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dione was prepared according to literature procedures [1]. The rest reagents were purchased and used as obtained. Acetone and ethanol, CP, were supplied by POCH Poland. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and triethylamine (TEA), CP, were supplied by Avocado, Germany, and ethylene oxide (EO), CP, by Merck, Germany.

Analytical methods

1H- and 13C-NMR spectra of the product were recorded with the use of a Bruker spectrometer (operating frequency 500 MHz). The compound was dissolved in deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (d6-DMSO). Hexamethyldisiloxane (HMDS) and tetramethylsilane (TMS) were used as an internal standard. All two-dimensional (2D) experiments (1H-COSY, 1H-NOESY, HSQC, and HMBC) were performed with the use of the manufacturer’s software. Proton spectra were assigned using COSY. Protonated carbons were assigned by HSQC. Quaternary carbons were assigned by HMBC.

The MS-ESI measurements were performed using the QExactive system (Thermo, Switzerland). The mass detector used was an LXQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer detector (Thermo Mod. Finnigan TM LXQTM) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source and then interfaced to a computer. The MS/MS parameters were as follows: positive mode; ESI source voltage, 5.0 kV; capillary voltage, 36 V; sheath gas flow rate, 11 arb; aux gas flow rate, 0 arb; sweep gas flow rate, 0 arb; capillary temperature, 320 °C; and scan range, 0–500 m/z. Samples were dissolved in methanol.

IR spectrum was recorded on a Bruker ALPHA FT-IR spectrophotometer with samples prepared as KBr discs. The measurement resolution was 0.01 cm−1.

Elemental analysis (C, H, N) of the product was carried out using an elemental analyzer Vario EL III C, H, and N from Elementar.

UV-Vis spectrum was recorded at 25 °C in the range of 200–700 nm with a spectrometer Hewlett Packard 8943 in a methanol solution. The measuring cell was 1 cm thick.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data was collected on a Rigaku Oxford Diffraction SuperNova Double Source diffractometer with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å) at 100(2) K using CrysAlis RED software [27]. The multi-scan empirical absorption correction using spherical harmonics was applied as implemented in SCALE3 ABSPACK scaling algorithms [27]. The structural determination procedure was carried out using the SHELX package [28]. The structure was solved with direct methods, and then, successive least-squares refinements were carried out based on the full-matrix least squares on F2 using the XLMP program [28]. All H-atoms bound to C-atoms were positioned geometrically, with C–H equal to 0.93 Å or 0.97 Å for the aromatic and methylene H-atoms, respectively, and constrained to ride on their parent atoms with Uiso(H) = xUeq(C), where x = 1.2. The hydroxyl H-atoms were located on a Fourier difference map and refined as riding with Uiso(H) = 1.5Ueq(O). The figures for this publication were prepared using ORTEP-3 and Mercury programs [29, 30]. The molecular interactions were identified and analyzed by the PLATON [24] and CrystalExplorer programs [26].

Quantum mechanical calculations

Quantum mechanical calculations were performed using the Gaussian 09, based on the density functional theory (DFT). Calculations were performed using the exchange-correlation functional Becke-3-Lee-Yang-Parr (B3LYP) [31,32,33] and the functional set 6-311++G(d,p) [34]. This combination of functional B3LYP and functional set is used as the most appropriate tool to optimize the structure of organic compounds [35, 36]. The theoretical calculations were made with the inclusion of Grimme dispersion correction which took into account intramolecular hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions. Frequency calculations were performed at the same level of theory as the geometry optimization to confirm whether the obtained structures were minima (no imaginary frequency) or transition states (only one imaginary frequency). Gibbs free energy values were read by the application Notepad++ and EDA-Reader [37, 38]. The mixtures’ contents of conformers were determined based on the value of Gibbs free energy (enthalpy) using formula:

where:

- C j :

-

molar concentration of the j-th conformer,

- Ei, Ej:

-

Gibbs free energy for, respectively, the i-th and j-th conformers,

- F c :

-

unit conversion factor 1 kcal/mol-hartree = 627.5095,

- R :

-

gas constant 1.987 cal/(K mol),

- T :

-

temperature 298.15 K.

Visualization of the structures was performed using the software GaussView and Mercury [30, 39].

Synthetic procedure

General procedure for synthesis of 3-{2-[1,3-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-oxo-4-phenylimidazolidin-5-yl]-phenyl}-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one (Fig. 19)

1.38 g (5 mmol) 1-phenyl-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dion, 20 cm3 of DMSO, 0.1 g (1 mmol) triethylamine (TEA), and 0.66 g (15 mmol) EO were placed into a high pressure reactor with a volume of 100 cm3. The reaction mixture was stirred with a magnetic stirrer and heated to a temperature of 70–80 °C. The reaction was terminated when the sample of the reaction mixture showed no weight loss (when measured on an analytical balance) and its epoxy number (EP) was zero. EP was determined according standard [40]. DMSO was distilled under reduced pressure (p = 7 mmHg, liquid distillation temperature 65–110 °C, vapor distillation temperature 68–72 °C). The reaction product was precipitated with acetone and then crystallized from ethyl alcohol. The purity of substance was monitored by TLC (elution systems chloroform—ethanol, 9:1) on Alugram SIL G/UV254 foils (Macherey-Nagel).

3-{2-[1,3-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-oxo-4-phenylimidazolidin-5-yl]phenyl}-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one: yield 74%, mp = 162–163 °C; IR (KBr), ν = 3453.4 and 3320.3 (s, O–H valence), 2932.9 (w, –CH2–, asym. valence), 2892.2 (w, –CH2–, sym. valence), 1738.0 (s, C=O, valence), 1662.2, 1600.3, 1503.3, 1478.2 (s, skel. Ph ring), 1147.4 (w, C–H planar def.), 752.9 and 679.6 (s, non-planar def.), 1081.2 and 1048.0 (m, C–O–H, valence) [cm−1]; ESI-MS: m/z 410 [M + H]+ (100%). ESI-MS/MS of precursor ion m/z 410: m/z 392 [M + H-H2O]+, 382 [M + H-C2H4]+, 374 [M + H-2H2O]+, 364 [M + H-C2H4-H2O]+, 354 [M + H-2C2H4]+, 305 (100%); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, d6-DMSO), δ = 2.65 (1 H, dt, –N–CH2–, J3,2 = 8.60 Hz, J3,3′ = 5.64 Hz), 3.45 (2 H, t, –N–CH2–, J25,26 = 6.79 Hz), 3.58 (2H, t, –CH2–OH, J25,26 = 6.73 Hz), 3.62 (2 H, t, –N–CH2–, J23,24 = 7.08 Hz), 3.68 (1 H, dt, –N–CH2–, J2,3 = 8.89 Hz, J3,3′ = 5.62 Hz,), 3.72 (2H, t, –CH2–OH, J23,24 = 7.02 Hz), 4.08 (1 H, dt, –O–CH2–, J2,3 = 8.34 Hz, J2,2′ = 8.25 Hz), 4.23 (1H, dt, –O–CH2–, J2,3 = 8.78 Hz, J2,2′ = 5.71 Hz), 4.80 (2 H, s, –OH), 7.19 (2 H, m, C18H and C22H), 7.29 (2 H, m, C20H and C9H), 7.33 (3 H, m, C19H and C21H and C7H), 7.42 (1 H, m, C8H), 7.53 (1 H, m, C10H) [ppm]; 13C-NMR (d6-DMSO), δ = 155.27 (C5), 153.21 (C15), 137.35 (C6), 133.40 (C17), 133.14 (C10), 129.42 (C8), 129.02 (C18), 128.96 (C22), 128.43 (C9), 127.77 (C20), 126.61 (C19 and 21), 125.80 (C7), 125.32 (C11), 120.06 (C13), 117.62 (C12), 62.03 (C2), 58.51 (C24), 58.43 (C26), 45.42 (C3), 44.05 (C25), 43.58 (C23) [ppm]; EA, Anal. Calcd for C22H23N3O5: C, 64.54; H, 6.07; N, 10.26. Found: C, 64.81; H, 6.09; N, 10.30. UV: 262, 335 [nm].

Conclusions

Reaction of 1-phenyl-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dione with 3-molar excess of ethylene oxide had an unexpected course. In the synthesis conditions of the alcohol and diol with imidazoquinazoline ring, in the presence of 3-molar excess of ethylene oxide, the imidazoquinazoline ring was opened. Then, 3-{2-[1,3-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-oxo-4-phenylimidazolidin-5-yl]phenyl}-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one was yielded. It contained the imidazole and oxazole rings in its structure. This was a result of intramolecular reaction of carbonyl group (C5) of the intermediate diol (7) with 2-hydroxyethyl group linked to nitrogen atom no. 6. Then, quinazoline ring was opened and oxazole ring was formed. Next, the imidazole ring reacted with the third mole of ethylene oxide.

The necessary condition for the above reaction was an excess of ethylene oxide higher than 2 molar. The possibility of addition of the intermediate product to the next ethylene oxide molecule caused the opening of the quinazoline ring of diol (7) and formation of oxazole ring.

The driving force of the intramolecular substitution was the shape of HOMO orbitals (distribution of electron density in diol (7) molecule). The electron density deficit at carbon no. 5 of carbonyl group determined the entire reaction course.

The reaction of diol (7) with the third mole of ethylene oxide was controlled by kinetics. The Gibbs free energy of transition state of diol (7) transformation has a lower value than that of the diol reaction with the third mole of ethylene oxide.

The new product obtained was characterized by the spectroscopic method, and its structure was confirmed beyond all doubt by means of crystallography.

In this way, a new method of obtaining diols with imidazole ring comprising oxazole ring additionally was found.

The obtained diol may have potential biological activity, e.g., anti-cancer.

References

Klasek A, Koristek K, Lycka A, Holcapek M (2003) Unprecedented reactivity of 3-amino-1H,3H-quinoline-2,4-diones with urea: an efficient synthesis of 2,6-dihydroimidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-diones. Tetrahedron 59:1283–1288

Klasek A, Koristek K, Lycka A, Holcapek M (2003) Reaction of 1-alkyl/aryl-3-amino-1H,3H-quinoline-2,4-diones with urea. Synthetic route to novel 3-(3-acylureido)-2,3-dihydro-1H-indol-2-ones, 4-alkylidene-10H-spiro[imidazolidine-5,30-indole]-2,20-diones, and 3,3a-dihydro-5H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinoline-2,4-diones. Tetrahedron 59:5279–5288

Klasek A, Holcapek M, Lycka A, Hoza I (2004) Reaction of 3-aminoquinoline-2,4-diones with nitrourea. Synthetic route to novel 3-ureidoquinoline-2,4-diones and imidazo[4,5-c]quinoline-2,4-diones. Tetrahedron 60:9953–9961

Szyszkowska A, Trzybiński D, Woźniak K, Klasek A, Zarzyka I (2017) Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization and DFT calculations of monohydroxyalkylated derivatives of 1-phenyl-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dione. J Mol Struct 1127:708–715

Szyszkowska A, Trzybiński D, Pawlędzio S, Woźniak K, Klasek A, Zarzyka I (2018) New diols with imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dione ring. J Mol Struct 1153:230–238

Alagarsamy V, Solomon VR, Murugan M, Sankaranarayanan R, Periyasamy P, Deepa R, Anandkumar TD (2008) Synthesis of 3-(2-pyridyl)-2-substituted-quinazolin-4(3H)-ones as new analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents. Biomed Pharmacother 62:454–461

Al-Omary F, Abou-Zeid L, Nagi M, Habib e-SE, Abdel-Aziz AA, El-Azab AS, Abdel-Hamide SG, Al-Omar MA, Al-Obaid AM, El-Subbagh HI (2010) Non-classical antifolates. Part 2: synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular modeling study of some new 2,6-substituted-quinazolin-4-ones. Bioorg Med Chem 18:2849–2863

Alagarsamy V, Raja-Solomon V, Parthiban P, Dhanabal K, Murugesan S, Saravanan G, Anjana G (2008) Synthesis and pharmacological investigation of novel 4-(4-ethyl phenyl)-1-substituted-4H-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]quinazolin-5-ones as new class of H1-antihistaminic agents. J Heterocyclic Chem 45:709–715

Rosenberg J, Gustafsson F, Galatius S, Hildebrandt PR (2005) Combination therapy with metolazone and loop diuretics in outpatients with refractory heart failure: an observational study and review of the literature. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 19:301–306

Barker AJ (2001) Quinazoline derivatives and their use as anti-cancer agents. EP Patent 0,635,498, January 25, 2001

Jackson HC, Hansen HC, Kristiansen M, Suzdak PD, Klitgaard H, Judge ME, Swedberg MDB (1996) Anticonvulsant profile of the imidazoquinazolines NNC 14-0185 and NNC 14-0189 in rats and mice. Eur J Pharmacol 308:21–30

Li G, Kakarla R, Gerritz SW, Pendri A, Mac B (2009). Tetrahedron Lett 50:6048–6052

Chena Z, Huangb X, Yanga H, Dingd W, Gaoa L, Yea Z, Zhangd Y, Yud Y, Loua Y (2011) Anti-tumor effects of b-2, a novel 2,3-disubstituted 8-arylamino-3h-imidazo[4,5-g]quinazoline derivative, on the human lung adenocarcinoma a549 cell line in vitro and in vivo. Chem Biol Interact 189:90–99

Madhavi S, Sreenivasulu R, Yazala JP, Raju RR (2017) Synthesis of chalcone incorporated quinazoline derivatives as anticancer agents. Saudi Pharmacol J 25:275–279

Domány G, Gizur T, Gere A, Takács-Novák K, Farsang G, Ferenczy GG, Tárkányi G, Demeter M (1998). Eur J Med Chem 33:181–187

Abuelizz HA, El-Dib RA, Marzouk M, Al-Salahia R (2018) In vitro evaluation of new 2-phenoxy-benzo[g][1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]-quinazoline derivatives as antimicrobial agents. Microb Pathog 117:60–67

Hoener M, Wichmann J (2015) Imidazole derivatives, WO2016193235A1

Huang Z, Sendzik M (2009) Disubstituted imidazole derivatives as modulators of RAF kinase, WO2010100127A1

Adams JL, Boehm JC (1996) 4,5-disubstituted imidazole compounds, US6414150B1

Goetz D, Bergmeier S (2014) Imidazole and thiazole compositions for modifying biological signaling, CA2955582A1

Flohr A (2013) Imidazole derivatives, US9586970B2

Szczerba J (2009) Tworzywa i polimery o specjalnych właściwościach. Projektowanie i konstrukcje inżynierskie 19:11–19

Rabek JF (2008) Współczesna wiedza o polimerach- wybrane zagadnienia. PWN, Warsaw, p 202

Spek AL (2009) Structure validation in chemical crystallography. Acta Cryst D65:148–155

Wolff SK, Grimwood DJ, McKinnon JJ, Turner MJ, Jayatilaka D, Spackman MA, University of Western Australia (2012) CrystalExplorer (Version 3.1)

Wera M, Storoniak P, Trzybiński D, Zadykowicz B (2016) Intermolecular interactions in multi-component crystals of acridinone/thioacridinone derivatives: structural and energetics investigations. J Mol Struct 1125:36–46

(2008) CrysAlis CCD and CrysAlis RED, Oxford Diffraction. Oxford Diffraction Ltd, Yarnton

Sheldrick GM (2008) A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr 64:112–122

Farrugia LJ (1997) ORTEP-3 for windows - a version of ORTEP-III with a Graphical User Interface (GUI). J Appl Crystallogr 30:565–572

Macrae CF, Edgington PR, McCabe P, Pidcock E, Shields GP, Taylor R, Towler M, van de Streek J (2006) Mercury: visualization and analysis of crystal structures. J Appl Crystallogr 39:453–457

Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery Jr JA, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam MJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ (2009) Gaussian 09, Revision D.01. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford

Becke AD (1996) Density-functional thermochemistry. IV. A new dynamical correlation functional and implications for exact-exchange mixing. J Chem Phys 104:1040–1048

Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG (1988) Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys Rev B 37:785–798

Krishnan R, Binkley JS, Seeger R, Pople JA (1980) Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J Chem Phys 72:650–657

Tirado-Rives J, Jorgensen WL (2008) Performance of B3LYP density functional methods for a large set of organic molecules. J Chem Theory Comput 4:297–309

Check CE, Gilbert TM (2005) Progressive systematic underestimation of reaction energies by the B3LYP model as the number of C−C bonds increases: why organic chemists should use multiple DFT models for calculations involving polycarbon hydrocarbons. J Org Chem 70:9828–9834

Notepad++, https://notepad-plus-plus.org/

Hęclik K, Dębska B, Dobrowolski JC (2014) On the non-additivity of the substituent effect in ortho-, meta- and para-homo-disubstituted benzenes. RSC Adv 4:17337–17346

Dennington R, Keith T, Millam J (2009) GaussView, Version 5. Semichem Inc., Shawnee Mission

Polish standard PN-87/C-89085/13

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Interdisciplinary Centre for Mathematical and Computational Modelling in Warsaw for providing computer facilities for possibility of performing of the quantum mechanical calculations under grant G49-12.

The crystallographic study was carried out at the Biological and Chemical Research Centre, University of Warsaw, established within the project co-financed by European Union from the European Regional Development Fund under the Operational Programme Innovative Economy, 2007–2013.

NMR spectra were made in the Laboratory of Spectrometry, Faculty of Chemistry, Rzeszow University of Technology, and was financed from DS budget.

Antonin Klasek for the financial support from the internal grant of TBU in Zlin (No. IGA/FT/2017/005), funded from the resources of specific university research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

CCDC-CRM:001000968012 entries contain the supplementary crystallographic data (cif file) for this paper. This data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Szyszkowska, A., Hęclik, K., Pawlędzio, S. et al. Unprecedented reaction course of 1-phenyl-2H,6H-imidazo[1,5-c]quinazoline-3,5-dione with 3-M excess of ethylene oxide. Struct Chem 30, 1079–1094 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11224-018-1247-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11224-018-1247-5