Abstract

Because it is crucial for psychosocial adjustment and lifelong learning, education is the most relevant tool for ensuring inclusion and reducing inequalities. Due to its relationship with positive outcomes, such as life satisfaction, mental health, job performance or SES, academic achievement is a significant phenomenon that impacts students, families, and educational institutions. The present study sought to contribute to the field by reviewing the literature on the determinants that influence the objective achievements of a typical population of middle- to high-school students. Based on the PRISMA statement, a search for related studies was performed in the WoS, EBSCO, and PubMed databases, and 771 studies published between 1930 and 2022 were identified. After screening based on the analysis of abstracts, 35 studies met the selection criteria. The Bronfenbrenner ecological model served as the theoretical rationale for organizing the studies’ findings. The results of this review highlight the following determinants of school achievement: (i) Personal factors—gender, personality traits, cognitive abilities and academic background, motivation and self-constructs, stress and problem-solving strategies, and substance use; (ii) Contextual microsystem factors—(a) Family—parental educational background; parenting practices and interactions; parental involvement and support; (b) School—school location; school conditions, responsiveness, and practices; (c) Peers—peer-group disagreement management. This systematic review updates the existing empirical evidence on this topic and highlights the complexity of the phenomenon of academic achievement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Researchers worldwide have been interested in assessing academic achievement because of its immediate influence on decisions about schooling and work as well as its long-term impact on different aspects of an individual's life (Kelly & Donaldson, 2016). The importance of academic achievement can be observed in the growing global phenomenon of additional instruction to complement obligatory school hours (e.g., Zhang & Bray, 2017) and even to complete higher education (OECD, 2022). Private tutoring and after-school programs seem to deepen students’ understanding of certain subjects and promote academic performance, motivation, and socioemotional outcomes (Korpershoek et al., 2016; Kuger et al., 2016).

The literature provides both theoretical and empirical support for the idea that academic success is a multidimensional construct, with both objective and subjective dimensions contributing to its explanation (Araújo, 2017). While the subjective/experiential aspects include students' academic satisfaction with different domains at the individual and school group levels and their sense of personal development and engagement, the objective indicators of academic success correspond to academic achievement and are assessed by objective and quantifiable indicators, including general indicators such as procedural and declarative knowledge acquired by school systems, curricular grades or performance in educational tests, and progression to school academic levels, academic degrees and certificates (Araújo, 2017; Steinmayr et al., 2014). Although the complexity of the factors influencing academic success has been recognized, over time, the literature has paid particular attention to the more limited area of objective indicators, i.e., academic achievement (Cachia et al., 2018). Academic achievement tends to represent intellectual endeavour and therefore reflects, to a greater or lesser extent, an individual's intellectual capacity (Steinmayr et al., 2014).

This prevailing perspective has led to academic achievement being valued academically, professionally and socially (Cachia et al., 2018). Indeed, academic achievement (measured by GPA or standardized educational assessments) is a determinant of students' educational trajectories and, depending on the degrees and levels of achievement attained, can influence higher-education choices and career paths (Steinmayr et al., 2014), which can impact societal development in the long run. In addition, different reviews have supported the link between academic achievement and other positive life outcomes, such as life satisfaction and well-being (e.g., Bücker et al., 2018; Crede et al., 2015; Ng et al., 2015), mental health (e.g., Agnafors et al., 2021; Eisenberg et al., 2009) and/or career potential, job performance (Kuncel et al., 2004) and SES (Liu et al., 2022; Selvitopu & Kaya, 2023).

Nonetheless, students’ academic achievement is influenced by a multitude of diverse factors (Dings & Spinath, 2021) that may be closely associated with each other. Identifying these factors can be a particularly complex task (Gilar-Corbi et al., 2019). Therefore, this study aims to extend the understanding of the determinants of academic achievement from middle school to secondary school since it is crucial to produce tailored prevention and intervention efforts to address the associated risks and promote the engagement and accomplishments of these students.

1.1 Factors linked to academic achievement

Many studies conducted in recent years have proposed models that aim to identify the variables that influence students’ academic achievement. In general, the extensive variables investigated in various independent studies can be divided into four major groups: students’ personal factors, family, school, and broader social variables (Gilar-Corbi et al., 2019).

Regarding students’ personal factors, studies have focused on features such as gender and age (Pennington et al., 2021; Tsaousis & Alghamdi, 2022) or lifestyle-related factors such as health, diet, exercise, sleep, and drug use (Bugbee et al., 2019; Bugueño et al., 2017; Burrows et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2022). The literature in the field also encompasses vast research on the psychological and motivational aspects that affect achievement, such as students’ self-esteem, self-concept (Cheng, 2023; Steinmayr et al., 2019; Van der Beek et al., 2017), self-control, self-regulation, attributional style (Duckworth et al., 2019; Sahranavard et al., 2018), and orientation toward excellence (Martin et al., 2016). Moreover, emotional variables that can influence students’ performance, such as anxiety and humor (Camacho-Morles et al., 2021; Ford et al., 2012; Horn et al., 2021) or school-related feelings, have also been addressed. In addition, cognitive-related skills and intelligence (Finn et al., 2014; Lozano-Blasco et al., 2022), previous academic performance (Cordero & Manchón, 2014; Marks, 2023; Nath, 2012; Piñero et al., 2019), and study habits (Nath, 2012; Piñero et al., 2019) have been investigated.

The second type of factor related to academic attainment is family-related. Family-related factors encompass the family’s socioeconomic condition (Broer et al., 2019; Nath, 2012; Selvitopuhttps & Kaya, 2021), parents’ educational level and professional situation (Nath, 2012; Nunes et al., 2023; Shoukat et al., 2013), and family structure and dynamics (Chiu & Xihua, 2008; Shoukat et al., 2013). Support, supervision, and involvement from parents (Brajša‐Žganec et al., 2019; Lara & Saraccostti, 2019) as well as the value assigned to studying (Nath, 2012; Nunes et al., 2023; Sahranavard et al., 2018) were the most addressed family factors of students’ academic outcomes.

The third group of academic achievement indicators is school-related. The literature on these factors is somewhat inconclusive, with certain studies having found effects of these dimensions on academic achievement (Moreira et al., 2018; Spreitzer & Hafner, 2023), whereas others have argued that their influence is negligible or nonexistent (Hojo, 2012; Nath, 2012). Within this broader group, specific variables related to teaching practices (Gess-Newsome et al., 2019; Nath, 2012; Tomaszewski et al., 2022) have been identified in the literature. Moreover, the curriculum and learning opportunities provided by the school (Sahranavard et al., 2018) as well as school size and the teacher-to-student ratio (Cunningham et al., 2019; Nath, 2012) have also been shown to influence students’ achievement. Another important variable considered in research is the school environment and climate (Cardoso et al., 2011; Maxwell et al., 2017), which, if positive and secure, seems to positively impact academic achievement (Zysberg et al., 2021), while negative attitudes tend to hinder student engagement, causing poorer academic achievement (Forsberg et al., 2021).

Finally, there is less specificity regarding the broader social factors that influence academic achievement in the literature, possibly because they are associated with other groups of factors. Nonetheless, research has identified the school’s context and connection to the neighborhood (Ruiz et al., 2018; Xuan et al., 2019), the student’s area of residence (Nath, 2012), or even the school’s identity and culture (Hansen et al., 2022; Karvonen et al., 2018; Nath, 2012) as relevant correlates of academic achievement.

Researchers have tried to identify different possible predictors of achievement, and recent reviews and meta-analyses have explored the best predictors of high school achievement (Nunes et al., 2022) and tested the effect of interventions directed toward underachieving students (Snyder et al., 2019).

Based on the assumption that for any individual development to occur, interactions between personal characteristics and the environment over time are necessary (Bronfenbrenner, 1989), Bronfenbrenner's bioecological systems theory provides a comprehensive understanding of the various levels of influence on academic achievement. This model advocates that individuals are both influenced by and influencers of environmental contingences. According to Bronfenbrenner and Morris (1998), environmental contingencies are structured into 5 systems—the micro-, meso-, exo-, macro-, and chronosystems—as follows. The microsystem is a set of interpersonal relationships experienced in face-to-face environments. The mesosystem is a set of two or more settings that involve the person in development and together influence his or her development. The exosystem includes settings that do not directly involve the person but whose events affect or are affected by the person. The macrosystem includes cultural beliefs, political forces and lifestyles that interact with the individual. Finally, the chronosystem involves the passage of time through life and history. While interrelationships among various environments may have indirect effects on developing people, interactions at the microsystem level may have direct effects (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

In particular, bioecological systems theory has proven to be a useful means for discussing findings on independent topics related to academic achievement, such as family involvement and the home environment (e.g., Kocayörük, 2016; McBride et al., 2013; Mimrot, 2016), family-school relationships (e.g., Blandin, 2017; Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2017), school climate, neighborhood context and sense of belonging (Ruiz et al., 2018; Zaatari & Maalouf, 2022). Thus, this theory provides a relevant framework for studying academic achievement from a comprehensive and ecological perspective by acknowledging the dynamics of change in academic achievement, the active role of the individual in his or her development and the interactions between person and context. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has systematically reviewed the determinants of academic achievement from middle to high school considering bioecological systems theory. To address this need, the present study intends to contribute to the field by integrating the diverse literature and systematizing the research on the determinants of academic objective achievement in a typical student population attending middle to high school. In addition to contributing to early detection, practical preventive measures can be implemented at an early stage of the underachievement pathway (Snyder et al., 2021), considering the lower efficacy in high school and postsecondary education (Snyder et al., 2019). Therefore, this systematic review aimed to answer the following research question: what are the determinants of the academic objective achievement of typical students from middle to high school?

2 Method

2.1 Search strategy

Studies were identified through a search of EBSCO, PubMed, and Web of Science. The reference lists of the selected studies were also reviewed to identify other relevant studies. The search equation in EBSCO was as follows: TI (“school failure” OR “academic failure” OR “school underachievement” OR “educational underachievement” OR “academic underachievement” OR “academic achievement” OR “academic success” OR “school success”) AND TI (predictor* OR indicator* OR factor* OR determinant* OR correlation*). In PubMed, the search equation was (“school failure”[Title] OR “academic failure”[Title] OR “school underachievement”[Title] OR “educational underachievement”[Title] OR “academic underachievement”[Title] OR “academic achievement”[Title] OR “academic success”[Title] OR “school success”[Title]) AND (predictor*[Title] OR indicator*[Title] OR factor*[Title] OR determinant*[Title] OR correlation*[Title]). In Web of Science, the search equation was TI = (“school failure” OR “academic failure” OR “school underachievement” OR “educational underachievement” OR “academic underachievement” OR “academic achievement” OR “academic success” OR “school success”) AND TI = (predictor* OR indicator* OR factor* OR determinant* OR correlation*).

2.2 Study selection

Studies were considered for analysis if they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) the participants were aged 10–18 years (the general population attending middle to high school); (b) they were empirical studies; and (c) they included objective outcomes of students' achievement (e.g., GPA, grades, test scores). The exclusion criteria were (1) wrong publication type—case studies, single-case designs, qualitative studies, book chapters, theoretical essays, and systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis; (2) wrong population—preschool, primary school, higher education, vocational training, or specific populations (e.g., gifted students, students with disabilities, refugees, Latinos); and (3) wrong outcome—studies that did not mention the outcome variable of interest (e.g., studies that did not cover objective indicators of achievement, e.g., GPA, grades, test scores). The search was restricted by linguistic factors (e.g., Portuguese, English, Spanish, or French). Duplicate articles were excluded.

The studies were selected by two independent reviewers (DM and JC) based on titles and abstracts, according to recommendations from the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2010; Shamseer et al., 2015) and the established criteria.

The agreement index in the study selection process was assessed with Cohen’s kappa, which revealed almost perfect agreement: K = 0.94, p < 0.001 (Landis & Koch, 1977). Disagreements among the reviewers were discussed and resolved by consensus.

2.3 Identification and screening

Through the database searches, a total of 771 studies published between 1930 and 2022 were identified. Of the 771 studies, 693 were excluded, and 78 were considered for full-text analysis. Of the latter, 43 articles were eliminated for the following reasons: wrong outcome (n = 37) and wrong population (n = 6). After full-text analysis, 35 articles were retained for this review (Fig. 1). In total, 35 articles were included. The objectives, sample (N, age, % male, academic grade, and country), and main findings were extracted from each study. The Bronfenbrenner model served as the theoretical rationale for organizing the studies’ findings.

3 Results

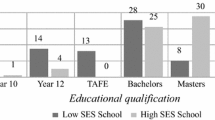

The review identified 36 studies examining determinants of academic achievement. A summary of the studies’ characteristics is presented in Table 1. Based on the Bronfenbrenner model, the studies’ results were organized according to personal factors and contextual factors. The contextual factors covered only the microsystem, i.e., the family, school and peer group levels. Table 2 presents the main factors and findings of the studies on academic achievement at the system level.

3.1 Personal factors

One of the most studied spheres of influence on academic achievement is at the individual level. Consistent with the literature, the present study found that the majority of the research was focused on determining the degree of influence of different students’ personal factors, whether biological, cognitive, personality-related, psychological or academic, on academic achievement.

3.1.1 Gender and gender stereotyping

The literature has highlighted the significance of gender differences in academic achievement. Heyder and Kessels (2013), who investigated both gender and gender stereotyping effects in school, found that boys presented relatively lower academic achievement than girls. The authors argued that a certain “feminization” of schools can lead to dissonance between boys’ self-concept and academic engagement, resulting in implicit gender stereotyping of boys’ school achievement (Heyder & Kessels, 2013). The results showed that the more intensely boys associated school with females and the more they assigned negative masculine traits to themselves, the lower their grades in the German language subject. For girls, their grades in both German and math were not related to their gender stereotyping of school (Heyder & Kessels, 2013).

3.1.2 Personality

The literature has shown a significant positive relation between different personality features and school achievement. In particular, in Sen and Hagtvet’s study (1993), creativity and certain personality dimensions, such as extraversion and theoretical and aesthetic value patterns, were related to academic achievement. Another study examined the personality traits of students rated by distinct groups of informants and how these traits related to academic achievement (measured by GPA). Specifically, self-, maternal and peer reports were collected using the Inventory of Child/Adolescent Individual Differences at two different time periods (at the end of elementary school and two years after high school), and conscientiousness and low extraversion were found to be consistent predictors of GPA (Smrtnik-Vitulic & Zupancic, 2011). Laidra et al. (2007) also reported that personality traits contribute to academic achievement in grades 6 to 12. In particular, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness were positively correlated and neuroticism was negatively correlated with GPA in almost every grade, while conscientiousness was the strongest predictor of GPA.

3.1.3 Cognitive abilities and academic background

Another personal variable that emerged in this study was the student’s cognitive ability. Specifically, Morosanova et al. (2015) conducted studies with two different samples, aiming to examine the impact of intelligence and cognitive characteristics on academic achievement. They found that cognitive characteristics were significant predictors of academic achievement in fields such as humanities, mathematics, and natural sciences (Morosanova et al., 2015). Additionally, Laidra et al. (2007) reported that, compared with students’ personality traits, intelligence was the best predictor of students’ GPA in all grades, with correlations of approximately 0.5.

Analyzing the influence of cognitive abilities, in general, and metacognition, in particular, Vrdoljak and Velki (2012) also found a positive effect on academic achievement, with students who scored better on metacognition tests also exhibiting higher grades. Moreover, the study of Marturano and Pizato (2015), which aimed to test a performance prediction model among 5th graders using predictors in the 3rd grade, revealed that academic skills in the 3rd grade were a predictor of achievement in the 5th grade (Marturano & Pizato, 2015).

Students’ cognitive abilities are likely to influence their academic background and trajectory. Mahimuang (2005) identified at the student’s individual level that students’ prior achievement (at grade 4) was the most relevant variable for predicting post achievement (grade 6) and was notably greater than other contextual factors.

Moreover, another study that examined predictors and risk factors for academic failure revealed that student attendance was positive and that grade retention was negatively associated with the cumulative grade point average (GPA; Lucio et al., 2011).

3.1.4 Motivation and self-constructs

Efforts have been made to identify noncognitive predictors of academic achievement. Regarding the impact of motivation on academic achievement, Dickhauser et al. (2016) found that the motivational dispositions of students had significant indirect effects on their intrinsic motivation and academic performance through their achievement goals. This study also revealed that fears regarding the possibility of failure had a moderating effect on the likelihood of success on mastery goals (Dickhäuser et al., 2016). Licht and Dweck (1984) performed a motivational analysis to understand individual differences in different academic subjects (e.g., mathematics vs. verbal subjects). The authors found that when more confusing material was presented in the beginning of a course, students with an attributional style toward “mastery” exhibited better achievement than did students with a “helpless” style. Nonetheless, if a similar learning task was presented without the confusing material, both student groups revealed equal levels of ease in learning the material. Thus, the results suggest that differences in achievement may be due to the fit between achievement orientations and the demands of certain skill areas (Licht & Dweck, 1984).

Steinmayr and Spinath (2009), who investigated the effects of motivation (ability self-perception, values, achievement motives and goals) on school achievement, demonstrated that most motivational constructs contribute to the prediction of school success beyond intelligence. In particular, their findings indicated that domain-specific assessed ability self-concepts and values explained most of the predicted domain-specific achievement variance. In both domains (German and math), ability self-concepts explained even more unique variance than intelligence. Moreover, the two domain-specific ability self-concepts still predicted grades when prior school achievement was controlled for. In this study, motivational constructs nearly explained as much unique variance in general school achievement as intelligence, which supports the authors’ perspective that motivation is a predictor of school achievement whose relative importance is at least comparable to intelligence.

The literature has also focused on the relevance of self-constructs to supporting academic achievement. A study by Bilge et al. (2014) that investigated the effect of self-efficacy on students’ achievement and burnout revealed that lower self-efficacy among students was associated with greater levels of burnout and a greater risk of losing their beliefs. Conversely, higher levels of self-efficacy were associated with increased academic achievement. Lucio et al. (2011) examined different variables that could be protective against academic failure and found that, independently, both self-efficacy and academic expectations were related to cumulative grade point average (GPA).

In a large study by Abad and López (2016), with a sample of 18,935 high school students from 99 educational institutions in Mexico, students’ personal factors were the strongest predictors of academic achievement, and in particular, self-esteem emerged as one of the strongest predictors analyzed. In a study by Stankov et al. (2012), the authors found that confidence was an important psychological construct, as it proved to be a better predictor of achievement than domain-specific (i.e., mathematics, English) measures of self-efficacy, self-concept, and anxiety. In a subsequent study (Stankov et al., 2014), the authors found that students' confidence explained the majority of the variance in mathematics achievement captured by the other self-constructs (self-efficacy and self-concept combined).

Romero et al. (2012) focused on the contextual and individual risk factors that have an impact on academic achievement. Specifically, the authors examined the effects of contextual variables, goals and self-regulation on academic achievement in a resilient group (with higher grades) vs. a nonresilient group (with lower grades) of high school students. The findings indicate that the nonresilient group was more influenced by contextual variables, whereas the resilient group was more affected by individual variables (e.g., self-regulation). That is, negative contextual variables had a significant impact on academic achievement in the nonresilience group but not in the resilience group because in the latter group individual variables (e.g., self-regulation) mitigated these effects (Romero et al., 2012).

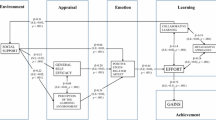

3.1.5 Stress and problem-solving strategies

Regarding the impact of affective-motivational variables related to stress, a study by Martínez-Vicente et al. (2019) revealed significant negative relationships between day-to-day stress (in health, school, and family domains) and academic achievement. More recently, a study by Valiente-Barroso et al. (2020) tested whether perceived childhood stress could be a predictor variable for academic achievement. The findings show that childhood stress has an inverse relationship with academic achievement. In addition, findings have indicated that students’ learning strategies and academic motivation play a mediating role in child stress by reducing its effects on academic achievement (Valiente-Barroso et al., 2020). Similarly, a study that tested an achievement prediction model among 5th graders using different predictors revealed that the perception of school stressors in the 3rd grade was a predictor of achievement in the 5th grade while controlling for the duration of exposure to early childhood education and socioeconomic conditions (Marturano & Pizato, 2015).

The findings of Steinmayr et al. (2018) for 8th and 9th graders suggested that the worry component of test anxiety was a negative predictor of academic achievement (measured by GPA) and subjective well-being after controlling for all other variables (Steinmayr et al., 2018).

Moreover, Hamlen (2014), who investigated middle and high school students’ strategies used to overcome challenges in both video games and homework assignments and whether these strategies are predictors of academic achievement in school, found that the types of strategies students used to overcome homework difficulties were not related to academic GPA, whereas video-game strategies were.

3.1.6 Substance use

A large study examined the relationship between substance use (i.e., of marijuana and alcohol) and academic indices (Patte et al., 2017). The results showed that students who used these substances were less likely to attend class regularly or finish their homework and were less prone to achieve high grades than students who did not use these substances. Moreover, the impact on academic goals varied according to substance and frequency of use.

In the study by Abad and López (2016), among personal, school-related and social factors, drug use was considered to be of paramount importance for academic achievement and was related to all three life domains of students.

3.2 Contextual/social microsystem factors

3.2.1 Family

Regarding family- or parental-related factors, a study by Hortaçsu and Üner (1993) revealed that both parental educational background and perceptions of control had direct and indirect effects on the academic achievement of children.

Hansen and Gustafsson (2015) aimed to understand the variation observed in the relationship between parental education and academic achievement (specifically, reading, mathematics and science achievement) across 37 countries that participated in both the PIRLS and the TIMSS 2011. The authors used the Gini index as a measure of economic inequality levels and the human development index (HDI) as a measure of overall societal development. The results indicated a negative correlation between the Gini index and the indirect effect of parental education on reading achievement and, to a lesser degree, on mathematics achievement (Hansen & Gustafsson, 2015).

In a study by Ginsburg and Bronstein (1993), which investigated familial influence on children’s motivational orientation and academic achievement, the authors found that parental behaviors and family styles that control children’s independent thinking and behavior—critical or punitive or uninvolved—were associated with a more extrinsic motivational orientation and poorer academic achievement, while parental behaviors and family style that were supportive and encouraging of children's autonomous expression and individual development were related to a more intrinsic motivational orientation and better academic achievement.

Karbach et al. (2013) examined perceived parental involvement according to four distinct dimensions: emotional responsivity, autonomy-supporting behavior, structure, and achievement-oriented control. The results showed that autonomy-supporting behavior and emotional responsivity were predictors of general cognitive ability and that high levels of achievement-oriented control and structure were unfavorable to academic achievement (Karbach et al., 2013). Similarly, a study by Choe (2020) revealed that reports of parents and adolescents diverged in regard to perceived parental support. Specifically, parental support reported by adolescents was more strongly associated with better academic achievement than parental support; however, academic support reported by parents was the strongest predictor of academic achievement in adolescents (Choe, 2020). Additionally, a study by Gangolu (2019) focused on adolescents (as adolescence is a period of high stress, social expansion and identity construction) and found that good parental involvement and personal adjustment have a significant positive impact on academic achievement.

Moreover, Porfeli et al. (2012) studied the connections between the work valences of parents and of children and valence perceptions, as well as how these relationships are related to the academic interest and achievement of the children. The findings revealed that children’s perceptions of their parents are mediators of the relationship between parents’ and children’s self-reported work valences and that children’s work valences are linked to academic interest and achievement (Porfeli et al., 2012).

The literature has also investigated the impact that interparental conflict and adverse childhood experience (ACE) can have on students’ achievement. Ghazarian and Buehler (2010) found that interparental conflict was a risk factor for poorer academic achievement, with youth self-blame, maternal acceptance and monitoring knowledge acting as mediators of this relationship. These results suggest that family interactions exert a significant impact on how young people perform academically (Ghazarian & Buehler, 2010).

3.2.2 School

For researchers focusing on the aspects that could promote or hinder students’ achievement, school, as one of the most important contexts of students’ socialization, is particularly relevant. Börkan and Bakis (2016) examined within-school vs. between-school factors that could explain differences in students’ achievement scores. The results showed that although most of the variance in students' scores between and within schools (73% and 19%, respectively) was explained by student-level variables, namely, students' sociodemographic background, school-level variables still accounted for 5% of the variance in students’ achievement scores (Börkan & Bakis, 2016).

Similarly, in another study by Mahimuang (2005), which examined the value-added contribution of individual and school factor variables to student achievement, it was found that although the best predictor of postachievement was the student's prior achievement, school practices also predicted student achievement. In addition, the study highlighted the effects of school location on student achievement: schools located far from district education offices face greater challenges in improving student achievement.

Other studies, such as that of Lucio et al. (2012), focused on school conditions, such as students’ perceptions of school safety, school belonging and school relevance, as well as positive teacher relationships and students’ achievement and found that each variable was independently associated with students’ GPA. In another study, Steinmayr et al. (2018) examined whether perceived school climate was a stronger predictor of academic achievement (measured by GPA) and subjective well-being than other variables that are relevant to both of these dimensions. The findings suggested that a positive school climate was a predictor of students’ academic achievement and well-being (Steinmayr et al., 2018). A study by Theis et al. (2019) found a significant relationship between students’ perceived fulfillment of needs and their graded performance. These findings support the importance of creating an optimal learning environment based on students’ basic needs since such an environment will have a positive effect on students’ scholastic attainment (Theis et al., 2019).

Because in recent years it has become common to use internet or computer tutoring with a program or application for additional instruction (ICTPAAI), a recent study (Zhu & Mok, 2020) sought to investigate whether students’ participation in and use of these technologies, in- or outside school, could be associated with better academic achievement. The results showed that students’ participation in ICTPAAI was negatively associated with their academic achievement at the end of the school year, with a significant amount of variance explained at the school level. These findings suggest that schools play an important role in students’ participation in ICTPAAI (Zhu & Mok, 2020) and could hinder the negative effect of ICTPAAI on students’ achievement.

3.2.3 Peers

Students’ peers and friends are relevant participants in daily experiences in school, and research has been dedicated to investigating the influence of such peers and friends on students' adaptation and adjustment to school. In this vein, a study examined early adolescent autonomy and relatedness during disagreements with friends as factors likely to predict academic achievement during the transition to high school and academic attainment into early adulthood. The results showed that autonomy and relatedness at age 13 predicted relative GPA increases from ages 13 to 15 and greater academic attainment by age 29. These findings remained valid after accounting for peer acceptance, social competence, scholastic competence, externalizing and depressive symptoms, which suggests an essential role for autonomy and relatedness in helping adolescents navigate challenges and obstacles in the transition to high school and into adulthood (Loeb et al., 2019).

4 Discussion

A multitude of factors play a role in students’ academic achievement. Thus, it is not easy to identify these factors given their diverse nature (Dings & Spinath, 2021) or the complex associations among them (Gilar-Corbi et al., 2019). To better understand this phenomenon, researchers in the field have addressed it extensively using diverse models and statistical procedures (Dings & Spinath, 2021). The present systematic review is intended to update the literature on the determinants of school achievement among the general student population from middle to high school, a period during which more effort and investment are crucial to promote positive and adaptive school pathways.

In general, research has mainly examined the individual/personal level and focused on students’ motivation and self-appraisal (e.g., motivation, goal valuation, self-efficacy, self-regulation, environmental perceptions, and psychosocial functioning) rather than on contextual or social factors (Steenbergen-Hu et al., 2020). The findings of the present study highlight the contribution of both personal and contextual microsystem factors to typical students’ academic achievement. In fact, this review identifies a multiplicity of personal factors influencing school achievement. This result is consistent with the findings of Abad and López (2016), who studied a sample of almost two thousand high school students and found that personal factors were the strongest indicators of academic achievement, followed by school-related and social factors. Additionally, Babarović et al. (2009) reported that approximately 40% of the variance in academic achievement was explained by student characteristics such as age, gender, and cognitive abilities; thus, academic achievement was the best predictor of academic achievement.

At the students’ personal level, this review identified students’ gender, personality and life skills as distinctive determinants of students’ achievement. Gender differences in academic success have long been documented in the literature. While girls tend to outperform boys in reading literacy in many countries, boys demonstrate greater competency in math and/or science (OECD, 2009). Nonetheless, studies including different types of assessments (both grades and standardized performance measures) have shown that boys on average earn lower grades than expected from their performance on ability or achievement tests (Duckworth & Seligman, 2006). These findings support the multiplicity of noncognitive factors that can influence academic achievement, in addition to students’ objective cognitive abilities. Personality traits were also demonstrated to be among the strongest factors of academic achievement in children and adolescents (Backmann et al., 2019; Israel et al., 2019), mainly because such factors are relatively stable and can potentiate and support students’ academic endeavors in the long run. The literature has shown that students who are persistent, achievement-oriented, effortful, careful, responsible, and well organized tend to manage academic assignments and learning more effectively, whereas students who are curious and interested and who seek new ideas and experiences manage academic-related problems in school more successfully (Backmann et al., 2019; Israel et al., 2019).

Moreover, cognitive-related abilities and academic background were also identified in this review as determinants of student achievement. The literature has highlighted the strong correlation between general intelligence and school grades and ages (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2005). In fact, academic performance and academic achievement are related to students’ cognitive profiles, namely, thinking and learning patterns, despite the differences between learning environments (Colling et al., 2022), which will impact students’ academic trajectories.

Students’ motivation and self-constructs were also addressed in this systematic review. Research has shown that students with greater motivation and self-regulation attain significantly better results, adopt a positive attitude toward learning, and successfully adapt to the changing conditions of the learning process, thus highlighting the importance of these factors in students’ successful school pathways (Duckworth et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2021).

Additionally, research focused on students’ characteristics shows that academic achievement is positively correlated with social skills and negatively correlated with behavioral problems, whether externalized (e.g., aggressive behavior, rules violation) or internalized (e.g., anxiety, depressed mood, somatic complaints; Stack & Dever, 2020). Moreover, the school context is typically understood by students as a relevant source of stress, mainly due to performance and achievement issues (Byrne et al., 2011). Similarly, students’ greater perception of stress at school is associated with weaker scholastic achievement (Ye et al., 2019). Therefore, consistent with the findings of this review, both students’ subjective experience of stress in school and their lack of coping strategies to deal with daily stressors can impact their achievement.

Other determinants were identified in the contextual factors, i.e., only at the microsystem level of the family, school and peers. At the familial level, parents’ educational background and their involvement in and support for students’ academic work are recognized as influencing factors of academic achievement. These findings are consistent with many studies showing that parents are highly influential with respect to their children’s academic achievement, mostly because parental involvement is a parental right and responsibility as well as a social need (Castro et al., 2015). Moreover, research has shown that home-based parental behavior has an impact on children’s achievement. Specifically, when parents are stricter or more controlling, their children tend to perform worse in school. Other home characteristics to be considered are parents’ attitudes about when to enroll children in school and how much to push them to advance through school (e.g., DeBaryshe et al., 2000; Fitzgerald et al., 1991; Ginsburg & Bronstein, 1993). These findings can have important implications for practice, e.g., in developing appropriate counseling and designing effective interventions (Rogers et al., 2009). Conversely, children’s exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), mostly in familial settings, has the opposite effect on students’ academic endeavors and can have long-term effects on their academic attainment. This finding is well illustrated in the literature. In fact, any type of violence that children are exposed to negatively impacts children’s development (Vaillancourt & McDougall, 2013). Thus, academic achievement, as an important indicator of children’s academic life, will likely decrease and can lead to grade retention in the case of ACEs (Fry et al., 2018). Thus, policy-makers should promote measures to combat these ACEs, focusing on social contexts and health as well as the relationships among them.

In particular, at the school level, characteristics and climate as well as students’ relationships with teachers and peers seem to influence students’ paths throughout academic cycles. In fact, schools, as a relevant context of socialization, should use all the necessary strategies to foster students’ engagement, motivation, and adjustment to academic pathways. In particular, schools can propose formal and informal activities involving students, teachers and communities to promote a positive and secure school climate as well as to foster students’ involvement and identification with school practices. Moreover, the literature has highlighted that teacher‒student relations occupy an important place in school life: both positivity and closeness in teacher‒student relations correlate with students’ psychological states, involvement in school, and academic achievement, while correlating negatively with expulsion from school and dropping out of school (Quin, 2017). Moreover, educational institutions can adopt specific measures to stimulate attendance and achievement. In particular, schools can help educate parents on the relevance of school attendance or promote after-school lessons for children who are behind on subjects or who are from underprivileged contexts as a way to mitigate the effects of socioeconomic status on academic achievement.

Peers at school are also relevant actors in students’ daily lives. In fact, when students share news of academic success with their friends and the friends respond with social support, this is shown to cause positive changes in school attitudes and perceived peer relationships (Wentzel et al., 2021). Conversely, a lack of support or positive feedback from friends when children share academic successes can lead to negative changes in perceived peer relationships (Wentzel et al., 2021). In fact, according to self-determination theory, the satisfaction of needs associated with autonomy and relatedness fosters intrinsic motivation and achievement (Ryan & Deci, 2017) since friendships characterized by autonomy and relatedness during a crucial period such as adolescence may have implications for academic achievement later in life.

There are limitations to this systematic review. First, the studies assessed in the review integrate different indicators of academic achievement (GPA, grades, test scores in specific domains/subjects). Thus, our interpretations should be viewed with caution. In addition, the present systematic review integrated studies with different study designs (e.g., experimental, cross-sectional, longitudinal) and/or provided limited data with which to calculate the effect sizes of the results, which limited the possibility of comparing and weighting each predictor in terms of student achievement. In addition, in view of the rapid development in the field, there is a risk of exclusion of the most recent studies, i.e., those appearing since the literature search was performed. Given these limitations, further studies could be conducted. To provide a more comprehensive analysis of academic achievement phenomena, it would be important to update this review based on a multidimensional perspective of achievement, including other relevant subjective indicators of achievement (e.g., students' or teachers' self-reports of achievement and performance) and other predictors of academic success, adjustment and/or well-being. Moreover, future reviews on the topic should also examine studies addressing the determinants of academic underachievement, allowing for further comparative analyses with the determinants of achievement. This systematic review provides evidence of a lack of studies investigating the impact of exosystem variables (e.g., parents’ work-family conflict and impact on students’ achievement) and macrosystem variables (e.g., political regime, economic situation of the country) on academic achievement. At the microsystem level, more studies can be developed considering other school factors (e.g., pedagogical practices, teacher support, inclusive education measures) and other peer factors (e.g., peer support, collaborative peer learning).

In this systematic review, different studies were compiled, providing an updated overview of the multiplicity of determinants contributing to typical students’ achievement from middle to high school. The findings presented here highlight the complexity of the achievement phenomenon and should be evaluated from a holistic perspective. In fact, to move beyond students’ particular idiosyncratic characteristics, there are preventive and collective activities that schools and communities should promote to minimize academic underachievement risk factors (e.g., involving parents in school activities, promoting a secure climate, planning activities to foster relationships between students and teachers, promoting after-school lessons for children who are behind, and providing pedagogical actions on drug use). In fact, the findings in this review have practical implications, e.g., for the development of prevention and intervention programs in school settings. In this vein, different programs and interventions to promote students’ attendance and adaptation as well as to avoid students’ absenteeism and dropouts have been developed in recent years (Kearney & Graczyk, 2020). Similarly, this updated systematization of the determinants of academic achievement highlights a need for further research into specific contextual factors that could support context-sensitive practices. In particular, a broader perspective of academic success, including achievement and other processes, could be further explored. Continuing to gather empirical evidence, as offered in the present systematic review, and developing appropriate strategies to promote achievement and address underachievement will proactively minimize potential risk factors for student achievement and lifelong learning.

References

*Abad, F., & López, C. (2016). Data-mining techniques in detecting factors linked to academic achievement. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2016.1235591

Agnafors, S., Barmark, M., & Sydsjö, G. (2021). Mental health and academic performance: A study on selection and causation effects from childhood to early adulthood. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(5), 857–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01934-5

Araújo, A. M. (2017). Sucesso no ensino superior: Uma revisão e conceptualização [Success in higher education: A review and conceptualization]. Revista de Estudios e Investigación en Psicología y Educación, 4(2), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.17979/reipe.2017.4.2.3207

Babarović, T., Burušić, J., & Šakić, M. (2009). Prediction of educational achievements of primary school pupils in the Republic of Croatia. Social Research, 18(4–5), 673–695.

Backmann, J., Weiss, M., Schippers, M. C., & Hoegl, M. (2019). Personality factors, student resiliency, and the moderating role of achievement values in study progress. Learning and Individual Differences, 72, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.04.004

*Bilge, F., Dost, M., & Çetin, B. (2014). Factors affecting burnout and school engagement among high school students: Study habits, self-efficacy beliefs, and academic success. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 14(5), 1721–1727. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2014.5.1727

Blandin, A. (2017). The home/school connection and its role in narrowing the academic achievement gap: An ecological systems theoretical perspective. Journal of Research on Christian Education, 26(3), 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/10656219.2017.1386146

*Börkan, B., & Bakis, O. (2016). Determinants of academic achievement of middle schoolers in Turkey. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 16(6), 2193–2217. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2016.6.0227

Brajša-Žganec, A., Merkaš, M., & Šakić Velić, M. (2019). The relations of parental supervision, parental school involvement, and child’s social competence with school achievement in primary school. Psychology in the Schools, 56(8), 1246–1258. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22273

Broer, M., Bai, Y., & Fonseca, F. (2019). Socioeconomic inequality and educational outcomes. IEA Research for Education (vol. 5). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11991-1_2

Bronfenbrenner U. (1989). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of child development: Six theories of child development, revised formulations and current issues (Vol. 6, pp. 187–249). JAI Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental process. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & R. M Lerner (Volume Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 993–1028). Wiley.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

Bücker, S., Nuraydin, S., Simonsmeier, B. A., Schneider, M., & Luhmann, M. (2018). Subjective well-being and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 74(17), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.02.007

Bugbee, B. A., Beck, K. H., Fryer, C. S., & Arria, A. M. (2019). Substance use, academic performance, and academic engagement among high school seniors. Journal of School Health, 89(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12723

Bugueño, M., Curihual, C., Olivares, P., Wallace, J., López-AlegrÍa, F., Rivera-López, G., & Oyanedel, J. C. (2017). Calidad de sueño y rendimiento académico en alumnos de educación secundaria [Quality of sleep and academic performance in high school students]. Revista Medica De Chile, 145(9), 1106–1114. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0034-98872017000901106

Burrows, T., Goldman, S., Pursey, K., & Lim, R. (2017). Is there an association between dietary intake and academic achievement: A systematic review. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 30(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12407

Byrne, D. G., Thomas, K. A., Burchell, J. L., Olive, L. S., & Mirabito, N. S. (2011). Stressor experience in primary school-aged children: Development of a scale to assess profiles of exposure and effects on psychological well-being. International Journal of Stress Management, 18(1), 88–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021577

Cachia, M., Lynam, S., & Stock, R. (2018). Academic success: Is it just about the grades? Higher Education Pedagogies, 3(2), 434–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2018.1462096

Camacho-Morles, J., Slemp, G. R., Pekrun, R., Loderer, K., Hou, H., & Oades, L. G. (2021). Activity achievement emotions and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 33(3), 1051–1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09585-3

Cardoso, A., Ferreira, M., Abrantes, J., Seabra, C., & Costa, C. (2011). Personal and pedagogical interaction factors as determinants of academic achievement. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 1596–1605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.402

Castro, M., Expósito-Casas, E., López-Martín, E., Lizasoain, L., Navarro-Asencio, E., & Gaviria, J. L. (2015). Parental involvement on student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 14, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EDUREV.2015.01.002

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2005). Personality and intellectual competence. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cheng, X. (2023). Looking through goal theories in language learning: A review on goal setting and achievement goal theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1035223. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1035223

Chiu, M. M., & Xihua, Z. (2008). Family and motivation effects on mathematics achievement: Analyses of students in 41 countries. Learning and Instruction, 18(4), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.06.003

*Choe, D. (2020). Parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions of parental support as predictors of adolescents’ academic achievement and self-regulated learning. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105172.

Colling, J., Wollschläger, R., Keller, U., Preckel, F., & Fischbach, A. (2022). Need for Cognition and its relation to academic achievement in different learning environments. Learning and Individual Differences, 93, 102110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102110

Cordero, J., & Manchón, C. (2014). Factores explicativos del rendimiento en educación primaria: Un análisis a partir de TIMSS 2011 [Explanatory factors for achievement in primary education: An analysis using TIMSS 2011]. Estudios sobre Educación, 27, 9–35. https://doi.org/10.15581/004.27.9-35 .

Crede, J., Wirthwein, L., McElvany, N., & Steinmayr, R. (2015). Adolescents’ academic achievement and life satisfaction: The role of parents’ education. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 52. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00052

Cunningham, C., Cunningham, S. A., Halim, N., & Yount, K. M. (2019). Public investments in education and children’s academic achievements. The Journal of Development Studies, 55(11), 2365–2381. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1516869

DeBaryshe, B., Binder, J., & Buell, M. (2000). Mothers’ implicit theories of early literacy instruction: Implications for children’s reading and writing. Early Child Development and Care, 160(1), 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/0030443001600111

*Dickhäuser, O., Dinger, F. C., Janke, S., Spinath, B., & Steinmayr, R. (2016). A prospective correlational analysis of achievement goals as mediating constructs linking distal motivational dispositions to intrinsic motivation and academic achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 50, 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.06.020

Dings, A., & Spinath, F. M. (2021). Motivational and personality variables distinguish academic underachievers from high achievers, low achievers, and overachievers. Social Psychology of Education, 24(6), 1461–1485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09659-2

Duckworth, A. L., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Self-discipline gives girls the edge: Gender in self-discipline, grades, and achievement test scores. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.198

Duckworth, A. L., Taxer, J. L., Eskreis-Winkler, L., Galla, B. M., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Self-control and academic achievement. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 373–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103230

Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E., & Hunt, J. (2009). Mental health and academic success in college. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 9(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.2191

El Zaatari, W., & Maalouf, I. (2022). How the Bronfenbrenner bio-ecological system theory explains the development of students’ sense of belonging to school? SAGE Open, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221134089

Finn, A. S., Kraft, M. A., West, M. R., Leonard, J. A., Bish, C. E., Martin, R. E., Sheridan, M. A., Gabrieli, C. F., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2014). Cognitive skills, student achievement tests, and schools. Psychological Science, 25(3), 736–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613516008

Fitzgerald, J., Spiegel, S., & Cunningham, J. (1991). The relationship between parental literacy level and perceptions of emergent literacy. Journal of Reading Behavior, 23(2), 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/10862969109547736

Ford, T. E., Ford, B. L., Boxer, C. F., & Armstrong, J. (2012). Effect of humor on state anxiety and math performance. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 25(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2012-0004

Forsberg, C., Chiriac, E. H., & Thornberg, R. (2021). Exploring pupils’ perspectives on school climate. Educational Research, 63(4), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2021.1956988

Fry, D., Fang, X., Elliott, S., Casey, T., Zheng, X., Li, J., & McCluskey, G. (2018). The relationships between violence in childhood and educational outcomes: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse and Neglect, 75, 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.021

*Gangolu, K. (2019). Adjustment and parental involvement as predictors of academic achievement of adolescents. Journal of Psychosocial Research, 14(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.32381/JPR.2019.14.01.7

Gess-Newsome, J., Taylor, J. A., Carlson, J., Gardner, A. L., Wilson, C. D., & Stuhlsatz, M. A. (2019). Teacher pedagogical content knowledge, practice, and student achievement. International Journal of Science Education, 41(7), 944–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2016.1265158

*Ghazarian, S., & Buehler, C. (2010). Interparental conflict and academic achievement: An examination of mediating and moderating factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9360-1

Gilar-Corbi, R., Veas, A., Miñano, P., & Castejón, J.-L. (2019). Differences in personal, familial, social, and school factors between underachieving and non-underachieving gifted secondary students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2367. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02367

*Ginsburg, G. S., & Bronstein, P. (1993). Family factors related to children’s intrinsic/extrinsic motivational orientation and academic performance. Child Development, 64(5), 1461–1474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02964.x

*Hamlen, K. R. (2014). Video game strategies as predictors of academic achievement. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 50(2), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.50.2.g

Hampden-Thompson, G., & Galindo, C. (2017). School–family relationships, school satisfaction and the academic achievement of young people. Educational Review, 69(2), 248–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2016.1207613

*Hansen, K., & Gustafsson, J. (2015). Determinants of country differences in effects of parental education on children’s academic achievement. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 4(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-016-0027-1

Hansen, K. Y., Radišić, D., Ding, Y., & Liu, X. (2022). Contextual effects on students’ achievement and academic self-concept in the Nordic and Chinese educational systems. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 10, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-022-00133-9

*Heyder, A., & Kessels, U. (2013). Is school feminine? Implicit gender stereotyping of school as a predictor of academic achievement. Sex Roles, 69(11–12), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0309-9

Hojo, M. (2012). Determinants of academic performance in Japan. Japanese Economy, 39(3), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.2753/JES1097-203X390301

Horn, A. M., Da Silva, K. A., & Patias, N. D. (2021). School performance and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in adolescents. Psicologia Teoria e Pesquisa, 37(1), e372117. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102.3772e372117

*Hortaçsu, N., & Üner, H. (1993). Family background, sociometric peer nominations, and perceived control as predictors of academic achievement. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 154(4), 425–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1993.9914741

Israel, A., Lüdtke, O., & Wagner, J. (2019). The longitudinal association between personality and achievement in adolescence: Differential effects across all Big Five traits and four achievement indicators. Learning and Individual Differences, 72, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.03.001

*Karbach, J., Gottschling, J., Spengler, M., Hegewald, K., & Spinath, F. (2013). Parental involvement and general cognitive ability as predictors of domain-specific academic achievement in early adolescence. Learning and Instruction, 23, 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.09.004

Karvonen, S., Tokola, K., & Rimpelä, A. (2018). Well-being and academic achievement: Differences between schools from 2002 to 2010 in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. Journal of School Health, 88(11), 821–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12691

Kearney, C. A., & Graczyk, P. A. (2020). A multidimensional, multi-tiered system of supports model to promote school attendance and address school absenteeism. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(3), 316–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00317-1

Kelly, D., & Donaldson, D. (2016). Investigating the complexities of academic success: Personality constrains the effects of metacognition. Psychology of Education Review, 40(2), 17–24.

Kocayörük, E. (2016). Parental involvement and school achievement. International Journal of Human and Behavioral Science, 2(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.19148/ijhbs.65987

Korpershoek, H., Harms, T., de Boer, H., van Kuijk, M., & Doolaard, S. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of classroom management strategies and classroom management programs on students’ academic, behavioral, emotional, and motivational outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 86(3), 643–680. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626799

Kuger, S., Klieme, E., Jude, N., & Kaplan, D. (2016). Assessing contexts of learning: An international perspective. Springer Nature.

Kuncel, N. R., Hezlett, S. A., & Ones, D. S. (2004). Academic performance, career potential, creativity, and job performance: Can one construct predict them all? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(1), 148–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.148

*Laidra, K., Pullmann, H., & Allik, J. (2007). Personality and intelligence as predictors of academic achievement: A cross-sectional study from elementary to secondary school. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(3), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.08.001

Lara, L., & Saracostti, M. (2019). Effect of Parental Involvement on children’s academic achievement in Chile. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1464. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01464

*Licht, B., & Dweck, C. (1984). Determinants of academic achievement: The interaction of children’s achievement orientations with skill area. Developmental Psychology, 20(4), 628–636. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.20.4.628

Liu, J., Peng, P., Zhao, B., & Luo, L. (2022). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement in primary and secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 2867–2896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-022-09689-y

*Loeb, E., Davis, A., Costello, M., & Allen, J. (2019). Autonomy and relatedness in early adolescent friendships as predictors of short- and long-term academic success. Social Development, 29(3), 818–836. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12424

Lozano-Blasco, R., Quílez-Robres, A., Usán, P., Salavera, C., & Casanovas-López, R. (2022). Types of intelligence and academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Intelligence, 10(4), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10040123

*Lucio, R., Hunt, E., & Bornovalova, M. (2012). Identifying the necessary and sufficient number of risk factors for predicting academic failure. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 422–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025939

Lucio, R., Rapp-Paglicci, L., & Rowe, W. (2011). Developing an additive risk model for predicting academic index: School factors and academic achievement. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 28(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-010-0222-9

*Mahimuang, S. (2005). Factors influencing academic achievement and improvement: A value-added approach. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 4(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-005-0677-1

Marks, G. N. (2023). The overwhelming importance of prior achievement when assessing school effects: Evidence from the Australian national assessments. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 34(1), 65–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2022.2102042

Martin, A. J., Collie, R. J., Mok, M. M., & McInerney, D. M. (2016). Personal best (PB) goal structure, individual PB goals, engagement, and achievement: A study of Chinese- and English-speaking background students in Australian schools. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12092

*Martínez-Vicente, M., Suárez-Riveiro, J., & Valiente-Barroso, C. (2019). Estrés cotidiano infantil y factores ligados al aprendizaje escolar como predictores del rendimiento académico [Childhood daily stress and factors linked to school learning as predictors of academic performance]. Ansiedad y Estrés, 25(2), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anyes.2019.08.002

*Marturano, E., & Pizato, E. (2015). Preditores de desempenho escolar no 5.º ano do ensino fundamental. Psico, 46(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-8623.2015.1.14850

Maxwell, S., Reynolds, K. J., Lee, E., Subasic, E., & Bromhead, D. (2017). The impact of school climate and school identification on academic achievement: Multilevel modeling with student and teacher data. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2069. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02069

McBride, B. A., Dyer, W. J., & Laxman, D. J. (2013). Father involvement and student achievement: Variations based on demographic contexts. Early Child Development and Care, 183(6), 810–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2012.725275

Mimrot, B. H. (2016). A study of academic achievement relation to home environment of secondary school students. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4(1), 30–40.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery, 8(5), 336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

Moreira, P. A. S., Dias, A., Matias, C., Castro, J., Gaspar, T., & Oliveira, J. (2018). School effects on students’ engagement with school: Academic performance moderates the effect of school support for learning on students’ engagement. Learning and Individual Differences, 67, 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.07.007

*Morosanova, V., Fomina, T., & Bondarenko, I. (2015). Academic achievement: Intelligence, regulatory, and cognitive predictors. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 8(3), 136–156. https://doi.org/10.11621/pir.2015.0311

Nath, S. (2012). Factors influencing primary students’ learning achievement in Bangladesh. Research in Education, 88(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.7227/RIE.88.1.5

Ng, Z. J., Huebner, S. E., & Hills, K. J. (2015). Life satisfaction and academic performance in early adolescents: Evidence for reciprocal association. Journal of School Psychology, 53(6), 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2015.09.004

Nunes, C., Oliveira, T., Castelli, M., & Cruz-Jesus, F. (2023). Determinants of academic achievement: How parents and teachers influence high school students’ performance. Heliyon, 9(2), e13335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13335

Nunes, C., Oliveira, T., Santini, F. D. O., Castelli, M., & Cruz-jesus, F. (2022). A weight and meta-analysis on the academic achievement of high school students. Education Sciences, 12(5), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12050287

OECD. (2009). Equally prepared for life? How 15-year-old boys and girls perform in school. OECD.

OECD. (2022). Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/3197152b-en

*Patte, K., Qian, W., & Leatherdale, S. (2017). Marijuana and alcohol use as predictors of academic achievement: A longitudinal analysis among youth in the COMPASS Study. Journal of School Health, 87(5), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12498

Pennington, C. R., Kaye, L. K., Qureshi, A. W., & Heim, D. (2021). Do gender differences in academic attainment correspond with scholastic attitudes? An exploratory study in a UK secondary school. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12711

Piñeiro, I., Estévez, I., Freire, C., de Caso, A., Souto, A., & González-Sanmamed, M. (2019). The role of prior achievement as an antecedent to student homework engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 140. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00140

*Porfeli, E., Ferrari, L., & Nota, L. (2012). Work valence as a predictor of academic achievement in the family context. Journal of Career Development, 40(5), 371–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845312460579

Quin, D. (2017). Longitudinal and contextual associations between teacher–student relationships and student engagement. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 345–387. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316669434

Rogers, M., Theule, J., Ryan, B., Adams, G., & Keating, L. (2009). Parental involvement and children’s school achievement: Evidence for mediating processes. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 24(1), 34–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573508328445

*Romero, J., Lugo, S., Hernández, Z., & Villa, E. (2012). Predictores del rendimiento académico en adolescentes com disposiciones resilientes y no resilientes [Predictors of academic performance in adolescents with resilient and non-resilient dispositions]. Revista De Psicología, 30(1), 48–74.

Ruiz, L. D., McMahon, S. D., & Jason, L. A. (2018). The role of neighborhood context and school climate in school-level academic achievement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61(3–4), 296–309. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12234

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press.

Sahranavard, S., Miri, M. R., & Salehiniya, H. (2018). The relationship between self-regulation and educational performance in students. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 7, 154. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_93_18

Selvitopu, A., & Kaya, M. (2023). A Meta-Analytic Review of the Effect of Socioeconomic Status on Academic Performance. Journal of Education, 203(4), 768–780. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220574211031978

Selvitopuhttps, A., & Kaya, M. (2021). A meta-analytic review of the effect of socioeconomic status on academic performance. Journal of Education, 203(4), 768–780. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220574211031978

*Sen, A. K., & Hagtvet, K. A. (1993). Correlations among Creativity, Intelligence, Personality, and Academic Achievement. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 77(2), 497–498. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1993.77.2.497

Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L. A., & PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ, 350, g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

Shoukat, A., Ilyas, M., Azam, R., & Ch, A. H. (2013). Impact of parents’ education on children’s academic performance. Secondary Education Journal, 2(1), 53–59.

*Smrtnik-Vitulić, H., & Zupančič, M. (2011). Personality traits as a predictor of academic achievement in adolescents. Educational Studies, 37(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055691003729062

Snyder, K. E., Carrigm, M. M., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2021). Developmental pathways in underachievement. Applied Developmental Science, 25(2), 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1543028

Snyder, K. E., Fong, C. J., Painter, J. K., Pittard, C. M., Barr, S. M., & Patall, E. A. (2019). Interventions for academically underachieving students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 28, 100294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100294

Spreitzer, C., & Hafner, S. (2023). Effects of characteristics of school quality on student performance in secondary school: A scoping review. European Journal of Educational Research, 12(2), 991–1013. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.12.2.991

Stack, K. F., & Dever, B. V. (2020). Using internalizing symptoms to predict math achievement among low-income urban elementary students. Contemporary School Psychology, 24, 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-019-00269-6

*Stankov, L., Lee, J., Luo, W., & Hogan, D. J. (2012). Confidence: A better predictor of academic achievement than self-efficacy, self-concept and anxiety? Learning and Individual Differences, 22(6), 747–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.05.013

*Stankov, L., Morony, S., & Lee, Y. (2014). Confidence: The best non-cognitive predictor of academic achievement? Educational Psychology, 34(1), 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.814194

Steenbergen-Hu, S., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Calvert, E. (2020). The Effectiveness of Current Interventions to Reverse the Underachievement of Gifted Students: Findings of a Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Gifted Child Quarterly, 64(2), 132–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986220908601

Steinmayr, R., Meiǹer, A., Weideinger, A. F., & Wirthwein, L. (2014). Academic achievement. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/OBO/97801997568100108

*Steinmayr, R., Heyder, A., Naumburg, C., Michels, J., & Withwein, L. (2018). School-related and individual predictors of subjective well-being and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2631–2647. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02631

*Steinmayr, R., & Spinath, B. (2009). The importance of motivation as a predictor of school achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 19(1), 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2008.05.004

Steinmayr, R., Weidinger, A. F., Schwinger, M., & Spinath, B. (2019). The importance of students’ motivation for their academic achievement – Replicating and extending previous findings. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1730. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01730

*Theis, D., Sauerwein, M., & Fischer, N. (2019). Perceived quality of instruction: The relationship among indicators of students’ basic needs, mastery goals, and academic achievement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(S1), 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12313

Tomaszewski, W., Xiang, N., Huang, Y., Western, M., McCourt, B., & McCarthy, I. (2022). The impact of effective teaching practices on academic achievement when mediated by student engagement: Evidence from Australian high schools. Education Sciences, 12, 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12050358

Tsaousis, I., & Alghamdi, M. H. (2022). Examining academic performance across gender differently: Measurement invariance and latent mean differences using biascorrected bootstrap confidence intervals. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 896638. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.896638

Vaillancourt, T., & McDougall, P. (2013). The link between childhood exposure to violence and academic achievement: Complex pathways. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(8), 1177–1178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9803-3

*Valiente-Barroso, C., Martínez-Vicente, M., Cabal-García, P., & Alvarado-Izquierdo, J. (2020). Estrés infantil, estrategias de aprendizaje y motivación académica: Un modelo estructural predictor del rendimiento académico [Childhood stress, learning strategies and academic motivation: A predictive structural model of academic performance]. Revista De Psicología y Educación, 15(1), 46–66.

Van der Beek, J. P. J., Van der Ven, S. H. G., Kroesbergen, E. H., & Leseman, P. P. M. (2017). Self-concept mediates the relation between achievement and emotions in mathematics. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(3), 478–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12160

*Vrdoljak, G., & Velki, T. (2012). Metacognition and intelligence as predictors of academic success. Croatian Journal of Education, 14(4), 799–815.

Wentzel, K. R., Jablansky, S., & Scalise, N. R. (2021). Peer social acceptance and academic achievement: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(1), 157–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000468

Wu, H., Guo, Y., Yang, Y., Zhao, L., & Guo, C. (2021). A meta-analysis of the longitudinal relationship between academic self-concept and academic achievement. Educational Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09600-1

Xuan, X., Xue, Y., Zhang, C., Luo, Y., Jiang, W., Qi, M., & Wang, Y. (2019). Relationship among school socioeconomic status, teacher-student relationship, and middle school students’ academic achievement in China: Using the multilevel mediation model. PLoS ONE, 14(3), e0213783. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213783

Ye, L., Posada, A., & Liu, Y. (2019). A review on the relationship between Chinese adolescents’ stress and academic achievement. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 163, 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20265