Abstract

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) students face victimization in multiple contexts, including the educational context. Here, teachers can serve as an important resource for LGB students. However, teachers who are prejudiced against students from sexual minorities might not be able to fulfill this role. Accordingly, it is important to find out more about teachers' attitudes and their correlates, as such information can provide starting points for sensitization interventions in teacher education programs, which have the potential to improve the situation of LGB students in the school setting. In the present preregistered questionnaire study, we investigated the attitudes of 138 preservice teachers from the University of Luxembourg toward LGB students and tried to identify predictors of teachers’ attitudes. Results suggested that Luxembourgish preservice teachers hold mostly positive attitudes toward LGB students. Using correlation and multiple regression analyses, we identified the frequency of participants’ contact with LGB people in family or friend networks, hypergendering tendencies, sexual orientation, and religiosity as reliable predictors of attitudes toward LGB students. Age, gender, and right-wing conservatism did not reliably predict preservice teachers’ attitudes in the regression models. Our findings thus offer support for intergroup contact theory and have implications for teacher education in Luxembourg.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The present study examined preservice teachers’ attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) students at the University of Luxembourg to replicate findings from a study previously conducted by Gegenfurtner (2021), who investigated preservice teachers’ attitudes toward transgender students. We addressed various limitations the author pointed out and aimed to expand the study’s scope by analyzing the influence of another correlate, namely, hypergendering. In his study, Gegenfurtner had over 500 participants from a large German university who filled out his questionnaire, which not only assessed preservice teachers’ attitudes toward transgender students but also possible predictor variables, such as participants’ age, gender, and sexual orientation, as well as previous contact with transgender people, religiosity, and political preference. Gegenfurtner’s results showed that, in general, preservice teachers had positive attitudes toward transgender students. On the basis of intergroup contact theory, which we present later in this article, Gegenfurtner found that participants who had prior contact with or had a transgender individual in their family or friend network tended to have more positive attitudes toward transgender students. Furthermore, he found that less religious as well as left-wing liberal preservice teachers had more positive attitudes toward transgender students compared with their more religious and right-wing conservative peers. Finally, female preservice teachers were found to have more positive attitudes toward transgender students than male preservice teachers did.

In his limitations paragraph, Gegenfurtner (2021) addressed two issues we aimed to address in the current paper. That is, Gegenfurtner used feeling thermometer scales, adapted from Norton and Herek (2013), to assess attitudes using a one-dimensional, 101-point rating scale. However, he suggested that more explicit measures should be used to assess attitudes more accurately. The same applies to the attitudes’ correlates, which were assessed dichotomously, whereas Gegenfurtner suggested that they should be measured on a continuous scale.

Additionally, regarding the correlates of preservice teachers’ attitudes, we decided to explore whether hypergendering tendencies, which can be defined as adherence to traditional gender roles and their stereotypes (Hamburger et al., 1996), could predict preservice teachers’ attitudes. Even though there is some evidence that traditional gender role beliefs are linked to negative attitudes toward homosexuality, we decided to explore this possible correlate, as it has not previously been assessed in preservice teacher samples.

Whereas prior research has included both preservice and in-service teachers’ attitudes toward a multitude of sexual- and gender-minority students, such as transgender (e.g., Gegenfurtner, 2021) or queer youth (e.g., Kosciw et al., 2022), the present study exclusively focused on preservice teachers’ attitudes toward LGB students. Thus, as we report findings from the literature, we refer specifically to the minority groups examined in each respective paper.

1.1 Sexual diversity in the school setting

In a 2021 survey conducted in the United States by Gallup, researchers found that almost 21% of Americans born between 1997 and 2003 (Generation Z) identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT; Jones, 2022). Thus, compared with only 10.5% of Americans born between 1981 and 1996 (Millennials) surveyed in the same poll, an apparent trend for young people to identify as LGBT has become more visible. However, these LGBT youth are likely to face adversity, discrimination, and victimization not only in their lives in general but also in education. In the 2021 National School Climate Survey (Kosciw et al., 2022), 50.6% of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or other sexual or gender identity (LGBTQ+) students indicated feeling unsafe in school because of their sexual orientation, leading most of them (78.8%) to avoid school functions or extracurricular activities and one third of them (32.2%) to skip at least 1 day of school each month. Furthermore, LGBTQ+ students reported being verbally (60.7%) and physically (22.4%) harassed because of their sexual orientation, with almost one out of 10 reporting being physically assaulted (8.8%). A similar picture has been painted in Europe. In a large, Europe-wide study surveying over 93,000 LGBT people age 18 or older, almost half of the participants (47%) indicated that they had felt discriminated against in the 12 months preceding their participation in the survey, with young lesbian women between the ages of 18 and 24 being most likely to have faced discrimination (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014). In general, young LGBT people reported feeling more discriminated against (57% of 18- to 24-year-olds) than older LGBT people (45% of 25- to 39-year-olds and 38% of 40- to 54-year-olds). In the educational context, 18% of participants indicated that they felt harassed by school or university personnel. In addition, 67% of participants indicated that they had always hidden their sexual orientation at school or university, with only 4% of participants showing their sexual orientation openly. Compared with the presented EU averages, Luxembourg ranks among the countries where discrimination against LGBT people is less frequent, as a total of only 33% of Luxembourg’s LGBT people felt discriminated against, reflecting its high ranking on the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association’s (ILGA) rainbow map (rainbow-europe.org), which rates the tolerance of European countries toward the LGBT community on the basis of political and societal achievements. This claim can also be supported by the extensive work of Meyers et al. (2019), who reviewed multiple large international surveys and suggested that the Luxembourgish population’s attitudes toward LGBT people are mostly positive. In the context of education, however, Luxembourg sits only just below the EU average, with 16% of its LGBT population feeling harassed by school or university personnel (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014).

According to a meta-analysis synthesizing 18 individual studies with a total of over 55,000 middle and high-school LGBT students participating, young gay men in particular, but also young lesbian women, are more likely to experience high levels of school-based victimization compared with their heterosexual peers (Toomey & Russell, 2016). This victimization, a term that includes any form of aggressive behavior aimed at hurting another person (Toomey & Russell, 2016), contributes to emotional distress in LGBT students, who experience more depressive symptoms and are more likely to report self-harming behavior and suicidal ideation (Almeida et al., 2009). Victimization at school was also shown to be associated with absenteeism and lower academic achievement in LGB students (Birkett et al., 2014). Of course, the associations between victimization at school and emotional distress on the one hand and lower academic achievement on the other are not exclusive to LGBT students, as this problem also affects heterosexual students who face victimization for other reasons (Estévez et al., 2005; Nakamoto & Schwartz, 2010; Rigby, 2000; Toomey & Russell, 2016).

1.2 Why teacher attitudes matter

Bearing in mind the trend that more and more minors are identifying as LGBT, it should become more likely that future teachers will have at least one or two LGBT students in their classes. Therefore, “to minimize these negative school experiences for sexual minority children and adolescents, it is important to sensitize pre-service teachers early in their teaching careers and increase their attitudes toward these vulnerable groups of students […]” (Gegenfurtner et al., 2023, p. 510). The importance stems from the fact that teachers can serve as a protective resource for some students by preventing homophobic behavior (Glikman & Elkayam, 2019) and helping these students feel safer at school (Goldstein-Schultz, 2022; Kosciw et al., 2022; Lenzi et al., 2017). Further, teachers can also serve as role models, aiding character formation and teaching virtues such as honesty, fairness, and respect (Lumpkin, 2008). In another light, and hypothetically, experiencing non-heterosexual (queer) teachers as positive role models may positively influence all students’ acceptance of different sexual orientations and, at the same time, LGBT students’ gender identity (Gegenfurtner & Gebhardt, 2017). To make schools safer for LGBT students, professional development gives teachers important tools to support and protect this minority group (Russell et al., 2021). At the same time, antibullying policies in schools and so-called gender and sexuality alliances (GSAs) lead teachers to engage in LGBT-supportive behaviors more frequently than teachers who do not work in schools that have implemented such policies (Kosciw et al., 2022; Swanson & Gettinger, 2016).

Teachers’ attitudes toward LGBT students can be defined as psychological tendencies expressed by evaluating a student with a certain degree of approval or disapproval (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007). On the basis of their attitudes, especially prejudice and stereotypes (i.e., negative attitudes), teachers form certain expectations of their students (Reyna, 2008). Consequently, a teacher’s expectations hold the power to influence a student’s academic performance (Gentrup et al., 2020), an effect known as the Pygmalion Effect or the teacher expectancy effect (TEE), an effect that has been studied widely since it was introduced by Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) over 50 years ago. According to Rosenthal (1994), the mechanism underlying the Pygmalion effect could be as follows: A teacher forms their expectations toward a student on the basis of the information they have about that student. The teacher then modifies their behavior toward the student accordingly, thus implicitly communicating their expectations to the student. Consequently, if these expectations are high, the student gains the motivation to fulfill them, which eventually leads to better academic performance. If these expectations are low, the student loses motivation over time, making the student less committed to academic success, which leads to poorer academic performance. In general, the adverse effects on students’ academic performances of teachers with low expectations were found to be stronger than the positive effects of teachers with high expectations (Jussim et al., 1996). How high or low a teacher’s expectations ultimately are depends on various indicators, such as the students’ race, socioeconomic status, or gender (Ready & Wright, 2011). For instance, teachers tend to underestimate the potential of ethnic minority students (Tenenbaum & Ruck, 2007), students with low socioeconomic status backgrounds (Rist, 1970), and students with disabilities (Hurwitz et al., 2007). Evidence of the TEE toward LGBTQ+ students is scarce but should be expected, as the TEE is mainly applicable to students with particular surface characteristics that activate stereotypes in teachers, who then form biased expectations (Szumski & Karwowski, 2019). Thus, stereotypes play an important role as a starting point for TEEs. For example, Muntoni and Retelsdorf (2018) found that teachers with stronger stereotypical beliefs expected girls to perform better than boys on reading ability tests. In turn, girls who were graded by these teachers scored significantly higher on this test than boys.

1.3 Intergroup contact theory

One way to reduce prejudice toward and stereotyping of LGBT students may be to promote contact between teachers and these groups. Almost 70 years ago, Allport (1954) formulated the most influential statement about intergroup contact theory by postulating that, under optimal circumstances, mere social contact between two groups can effectively reduce intergroup prejudice. These circumstances include equal status between the groups in the contact situation, cooperatively pursuing common goals, and obeying the same authorities and laws. In an extensive meta-analysis, Pettigrew and Tropp (2006) concluded that their findings “provide substantial evidence that intergroup contact can contribute meaningfully to reductions in prejudice across a broad range of groups and contexts” (p. 766), even if the optimal circumstances described by Allport are not established. In addition, the authors identified the largest effects of reductions in prejudice for samples involving contact between straight people and gay men or lesbian women. This intergroup contact effect is quite robust. Even when members of one group feel threatened or discriminated against by outgroup members, the authors suggested that intergroup contact could still effectively reduce prejudice (Van Assche et al., 2023). Furthermore, intergroup contact was shown to be a strong moderator of the positive association between the implementation of equalitarian rights (e.g., legalization of same-sex marriages) and positive attitudes toward LGB people (Górska et al., 2017). For teacher samples, positive associations were found between social contact with LGBT people and reduced sexual prejudice, positive attitudes, and frequent interference against homophobic behavior at school (Baiocco et al., 2020; Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Grigoropoulos, 2022; Klocke et al., 2019; Zotti et al., 2019).

1.4 Hypergendering

In its essence, the term hypergender is used to describe men and women who adhere to exaggerated expressions of traditional gender roles (Kreiger & Dumka, 2006), with hypergender men being referred to as hypermasculine or “macho” (Mosher & Sirkin, 1984) and hypergender women being referred to as hyperfeminine (Murnen & Byrne, 1991). On the one hand, according to Mosher and Sirkin (1984), hypermasculine men are characterized by having callous sexual attitudes toward women (i.e., the belief that men must be dominant and women should be submissive during sexual intercourse), by perceiving violence as an acceptable way to express strength and dominance over other men, and by viewing danger as exciting because it activates a survival instinct in which dominance over a threatening environment is displayed. On the other hand, Murnen and Byrne (1991) proposed that a hyperfeminine woman determines her personal success by developing and maintaining a romantic relationship with a man, primarily uses her sexuality to maintain this relationship, and expects men to also adhere to their traditional gender role “of aggressive, sometimes forceful, initiators of sexual activity” (p. 481).

Research has found that hypergendering tendencies are associated with higher prejudice against LGBT people in U.S. university students (Caballero, 2013; Hackimer et al., 2021; Harbaugh & Lindsey, 2015; Kurdek, 1988; Whitley, 2001), heterosexual Filipino adults (Reyes et al., 2019), as well as in a broader, international context (Bettinsoli et al., 2020). But what does this association stem from? Kite and Deaux (1998, as cited in Whitley, 2001) suggested that one important source of prejudice lies in the gender belief system, a set of beliefs that include stereotypical beliefs about appropriate gender roles as well as perceptions of the people who violate those beliefs, including gay men and lesbians. As people with a traditional, rigid gender belief system expect others to fit into their constructed set of gender roles, psychological traits, and physical attributes, they tend to have more negative views of people who do not match their gender beliefs (e.g., gay men or lesbians) because their expectations are not met, and thus, negative attitudes arise (Whitley, 2001). Research has indicated that the strength of traditional gender belief systems may vary between cultures, for example, as Nierman et al. (2007) found that Chilean university students held more traditional gender role beliefs and, at the same time, were significantly more prejudiced toward lesbians and gay men than their peers from a U.S. university. Regarding the teacher education context, we were unable to find any research on the relationship between hypergendering tendencies and prejudice toward LGB students in preservice teachers.

1.5 Other correlates affecting attitudes toward LGB students

In addition to intergroup contact theory, Gegenfurtner et al. (2023) investigated other correlates of preservice teachers’ attitudes toward LGB students. These correlates include age, gender, sexual orientation, religiosity, and political preferences.

1.5.1 Age

Several studies have found that older teachers tend to have more negative attitudes toward sexual minority groups. For example, Page (2017) found that older teachers felt less comfortable using literature that included LGBT characters or storylines and felt less comfortable promoting LGBT literature (e.g., recommending an LGBT-themed book for pleasure reading) than younger teachers. Other studies investigating this relationship have mainly found that (preservice) teacher age was negatively correlated with favorable attitudes toward LGBT students (Andersen & Fetner, 2008; Baiocco et al., 2020; Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Hall & Rodgers, 2019).

1.5.2 Gender

Gender differences in sexual prejudice have been studied widely, and there seems to be a tendency for heterosexual men to express more negative attitudes toward sexual minorities than heterosexual women do and to have more hostile reactions toward gay men than they do toward lesbians (Ahrold & Meston, 2010; Chen & Chang, 2020; Glotfelter & Anderson, 2017; Vieira De Figueiredo & Pereira, 2021). One possible explanation was offered by Herek and McLemore (2013), who put this phenomenon into a psychodynamic perspective. They argued that being sexually prejudiced could serve as a disguise for one’s unconscious homosexual attractions, which are feared especially by men. Feelings of aversion, hostility, and disgust thus serve as a “defense against the overwhelming anxiety that would result if inadequately repressed homosexual urges were to become conscious” (p. 320). Vieira de Figueiredo and Pereira (2021) suggested that heterosexual men, compared with women, feel a stronger need to differentiate themselves from gay men through prejudice, discrimination, and aggressive behaviors. Women, on the other hand, “are more tolerant of transgressions of gender roles and have less interest in upholding the tradition of these roles” (Vieira De Figueiredo & Pereira, 2021, p. 10), as they encounter less societal pressure to maintain a powerful and dominant social position. Indeed, some research was able to identify significant gender differences that hinted that female preservice teachers endorse more positive attitudes toward LGBT students than their male peers do (Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Heras-Sevilla & Ortega-Sánchez, 2020). However, other research could not find significant gender differences in sexual prejudice in preservice teacher samples (Mudrey & Medina-Adams, 2006; Wyatt et al., 2008). Gender differences in sexual prejudice can thus be regarded as inconsistent among preservice teachers.

1.5.3 Sexual orientation

It appears evident that nonheterosexual teachers would not express negative attitudes toward LGBT students, as they should be able to relate to the students’ sexual identities and show greater empathy. Research investigating the relationship between teachers’ attitudes and teachers’ sexual orientation is quite limited. Whereas Hall and Rodgers (2019) could not find significant differences in heterosexual versus nonheterosexual teachers’ attitudes, a few studies found that heterosexual teachers had higher levels of prejudice toward LGBT students than nonheterosexual teachers (Foy & Hodge, 2016; Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Stucky et al., 2020). Herek and McLemore (2013), as well as Vieira de Figueiredo and Pereira (2021), argued that heterosexual people may tend to reaffirm their conformity with traditional gender roles by holding on to negative attitudes toward LGBT people.

1.5.4 Religiosity

Warmth-based virtues, such as compassion, love, or forgiveness, are endorsed by most religions (Worthington & Berry, 2005). However, research on LGBT attitudes has found that stronger religious adherence is associated with more prejudice against LGBT people among teachers (Baiocco et al., 2020; Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Hall & Rodgers, 2019; Page, 2017; Stucky et al., 2020). Herek and McLemore (2013) discussed several explanatory approaches such that they described sexual prejudice in religious people as serving either social-expressive, value-expressive, or defensive functions. The social-expressive function postulates that religious people are prejudiced against LGBT community members to strengthen their group membership and social status within a religious affiliation that is sexually prejudiced as well. The value-expressive function concerns strongly religious people whose identity is closely tied to their religious values. However, traditional religious teachings are not always LGBT-tolerant, leading the believer to be prejudiced against sexual minorities as a means of expressing their religiosity. Finally, the defensive function serves people who have fragile self-esteem or who are insecure about their gender or sexuality so that the negative perception of nonheterosexuality in religion reduces the believer’s anxiety and restores their self-esteem.

1.5.5 Political orientation

Similar to religiosity, political preferences are also related to attitudes toward LGBT people, such that right-wing conservatism is related to more prejudice against sexual minorities (Herek, 2009; Hoyt & Parry, 2018). This finding can be transferred to the classroom context, as right-wing conservative teachers have been found to display stronger prejudice toward LGBT students than left-wing liberal teachers do (Baiocco et al., 2020; Foy & Hodge, 2016; Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Hall & Rodgers, 2019; Heras-Sevilla & Ortega-Sánchez, 2020).

1.6 Hypotheses

On the basis of Gegenfurtner’s (2021) findings that we aimed to replicate and past research in the area of teachers' attitudes toward LGB students presented above, we postulated the following hypotheses: We expected that (1) our preservice teacher sample would have mostly positive attitudes toward LGB students; (2) frequent contact with LGB people would be a reliable predictor of positive attitudes; (3) hypergendering tendencies in preservice teachers would be a reliable predictor of negative attitudes; (4) positive attitudes would be reliability predicted by (a) younger age, (b) female gender, and (c) homosexual sexual orientation; and (5) negative attitudes toward LGB students would be reliably predicted by (a) religiosity and (b) right-wing conservatism.

2 Methods

Prior to data collection, the project was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Luxembourg on December 9, 2022. This study was preregistered (https://osf.io/24ajg), so we documented and captured the sampling and data collection procedures, hypotheses, materials, and methods before the data were collected. In the spirit of Open Science, anyone can check whether we have adhered to our plans and any modifications we have made. A deviation log documenting the methodological and analytical changes from the preregistered procedure can be found in “Appendix A”.

2.1 Sampling procedure

Participants were recruited from the University of Luxembourg teacher education programs (i.e., Bachelor of Education and Master of Education). Links to the online questionnaire were distributed to preservice teachers via email and in lecture halls, where the study was also briefly presented. We also asked student representatives to share the link to the questionnaire in the students’ social media groups. All participants were entered into a raffle for vouchers with a total value of 200€. Only participants who indicated they were studying to become a teacher and spoke German well enough to complete the questionnaire were eligible to fill it out. All questions were presented in German. The questionnaire was created with the SoSci Survey Platform (Leiner, 2019) and was available online for 5 months, from December 2022 to April 2023. Study participation was voluntary, and anonymity was guaranteed.

2.2 Participants

A total of 146 participants answered the questions on the SoSci Survey platform. After excluding the participants who filled out less than 50% of the questionnaire or finished the questionnaire in under five minutes, 138 participants remained and were included in the analyses. Of these, 99 (71.7%) identified as women and 39 (28.3%) as men, which represents the typical proportions in Luxembourgish teacher education and schools (Service des statistiques et analyses, 2018). No participants indicated that they identified as another gender. More than half of the participants were between 21 and 23 years of age (52.2%)—representing the sample’s mode—and about a quarter were between 24 and 26 (26.8%), the age group representing the sample’s median; 15.9% were between 18 and 20, whereas only 3.6% were between 27 and 29. Only two participants were 30 or older (1.4%).

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Attitudes toward LGB students

We applied a broad understanding of attitudinal values and beliefs following the ongoing project “Einstellungen von Lehramtsstudierenden: Implizite Assoziationen mit Schüler*innen” [Attitudes of Student Teachers: Implicit Associations with Pupils] (ELIAS; for more information, see https://www.uni-augsburg.de/de/fakultaet/philsoz/fakultat/empirische-unterrichtsforschung/forschung/elias/). The ELIAS project is being conducted by Gegenfurtner and colleagues, who kindly provided us with explicit attitudinal questionnaire items directed toward lesbian and gay students. No studies have been published on this project to date. The multidimensional ELIAS questionnaire is adapted from Hachfeld et al. (2012), and its items represent four subscales: enthusiasm, self-efficacy, stereotypes, and beliefs. We adapted the items to fit our differentiated approach better, which included three separate item blocks assessing attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and bisexual students, respectively. Further, we excluded the belief subscale. Contrary to our differentiated approach, the belief items reflected attitudes toward sexual diversity in general. Therefore, they could not be meaningfully tailored to reflect attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and bisexual students separately. Participants rated their agreement with the given statements on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items include “Teaching gay/lesbian/bisexual students is fun” (enthusiasm) and, reversed, “Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual students have less interest in the topics relevant in school.” (stereotypes). To represent an even broader spectrum of attitudes toward LGB students, we also used the Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Men Scale, Revised 5-Item Version (ATLG-5; Herek & McLemore, 2011), which includes somewhat stronger statements, and which was translated from English to German by the first author. To fit the aims of our study, the scale was adapted by replacing the more general term “people” with “students”. Five new items were created by changing the terms “lesbian” and “gay” to “bisexual” to assess attitudes toward bisexual students. Participants rated their agreement with the given statements on the same 7-point Likert scale as the ELIAS items. Sample items included “Male homosexuality/Female homosexuality/Bisexuality is a natural expression of sexuality in some students” and, reversed, “I think gay men/lesbians/bisexual students are disgusting.” All questionnaire items can be found in Appendix B (all in English). For all participants, the item blocks were presented in the same order: lesbian first, gay second, bisexual third.

For practical reasons, to keep the analyses manageable (i.e., all analyses needed to be carried out for attitudes towards lesbian, gay, and bisexual students separately) and given overall relatively high bivariate correlations within the ELIAS subscales and between the ELIAS subscales and the ATLG-5 scale, we combined all 16 attitudinal statements from both measures into a composite score. Items were coded so that a high score on the composite measure reflects positive attitudes, thereby yielding homogenous scales based on Cronbach’s alpha for attitudes toward lesbian (α = 0.89), gay (α = 0.87), and bisexual students (α = 0.88), respectively.Footnote 1

Finally, we measured attitudes using a 101-point feeling thermometer, an approach also used by Norton and Herek (2013) and adapted by Gegenfurtner (2021). The thermometer ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating warmer feelings toward LGB students. This question was repeated in each block, so participants indicated their position on the feeling thermometer for each sexual orientation. The instructions, adapted from Gegenfurtner (2021), were as follows: “Think of an imaginary thermometer with a scale from 0 to 100. The warmer or more positive your feelings about lesbian/gay/bisexual students are, the higher the number you should give. The colder or more negative your feelings are toward lesbian/gay/bisexual students, the lower the number. If you have neither positive nor negative feelings, please give a 50. Which number describes your feelings about lesbian/gay/bisexual students?”.

2.3.2 Social contact with LGB people

To assess the participants’ social contact with LGB people, we again presented three blocks of items, with each block devoted to one sexual orientation. We asked the participants how frequently they come in contact with LGB people in their family as well as in their close and extended circle of friends. We asked participants to give their answers on a scale ranging from 1 (never or very rarely) to 7 (very frequently).

2.3.3 Hypergendering

Hypermasculinity was assessed with the Hypermasculinity Inventory-Revised (HMI-R; Peters et al., 2007), whereas hyperfemininity was measured with the Hyperfemininity Scale (Murnen & Byrne, 1991). Regarding reliability, both teams of authors reported very good reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90 for the HMI-R; retest reliability r = 0.89 for the Hyperfemininity Scale). Both scales were translated from English into German by native German speakers and were shortened due to their lengthiness. As Peters et al. (2007) proposed a three-factor solution for the HMI-R, the scale was shortened so that we could include the four items that loaded best on each factor, which resulted in a 12-item scale. We then adapted the Hyperfemininity Scale to match the HMI-R in length and response format. We tried to make the adaptations as identical as possible to the adaptations Peters et al. (2007) had made to the original Hypermasculinity Inventory proposed by Mosher and Sirkin (1984). As Murnen and Byrne (1991) proposed a one-factor solution, we chose 12 items intuitively. We tried to select contemporary items that required the smallest number of changes in their formulations and appeared to cover all facets of the construct. The response format was changed from a forced-choice to a 10-point phrase completion format. Sample items for the hypermasculinity assessment included “When it comes to taking risks…” 1 (I like to play it safe) to 10 (I’m a high roller) and, reversed, “Any man who is a man…” 1 (Needs to have sex regularly) to 10 (Can do without sex). Sample items for the hyperfemininity assessment included “When I want something from a man…” 1 (I never use my sexuality to influence him) to 10 (I sometimes act sexy to get what I want), and, reversed, “Most of the time, women…” 1 (need a man to lead a happy life) to 10 (do not need a man to lead a happy life). In light of these adaptations, the reliability of the HMI-R was acceptable in the present male sample (N = 34, α = 0.77). Cronbach’s alpha could not be improved by removing any items. For the Hyperfemininity Scale, the reliability was questionable (N = 91 women, α = 0.62). Again, Cronbach’s alpha could not be improved by removing any items.

As we did not expect homosexual participants to identify with the hypergendering items, and as it makes no sense to provide, for instance, the hyperfemininity scale to participating men, we used a filter so that only heterosexual men got to answer the hypermasculinity scale and only heterosexual women got to answer the hyperfemininity scale. Homosexual participants did not answer any hypergendering items. Bisexual men answered the hypermasculinity scale and bisexual women the hyperfemininity scale.

2.3.4 Background variables

The background variables we assessed were age, gender, sexual orientation, religiosity, and right-wing conservatism. For the age assessment, we asked, “How old are you?” and the participants could indicate their age category, ranging from 1 (18–20 years) up to 5 (30 years or older), with each age category representing a range of 2 years. We used age ranges to foster anonymity. For gender, we asked, “What gender do you identify yourself as?” with the answer options 1 (female), 2 (male), and 3 (other). For sexual orientation, we asked, “Who are you sexually attracted to?” Response possibilities were 1 (women only), 2 (mostly women), 3 (more to women than to men), 4 (to both sexes equally), 5 (more to men than to women), 6 (mostly men), and 7 (men only). Religiosity was measured with the 10-item Intrinsic Religious Motivation Scale (Hoge, 1972), also used in a paper by Kranz et al. (2020), who made the scale available to us. In their paper, the scale showed excellent reliability (α = 0.95) and good internal consistency (α = 0.87) in the present study. Sample items included “Religious beliefs lie behind my whole approach to life,” and, reversed, “I refuse to let religion influence my everyday affairs,” with agreement ratings ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Finally, conservatism, representing a right-wing political orientation, was measured with nine items selected from the Machiavellianism-Conservatism scale’s conservatism subscale (Cloetta, 1997), which was found to have a retest reliability ranging from r = 0.65 to r = 0.84. The answer format was changed from a 6-point Likert scale to a 7-point Likert scale in accordance with other scales from the questionnaire. Sample items included “It lies in human nature that humans need someone to look up to,” and, reversed, “Our society still prevents the satisfaction of important human needs,” with agreement ratings ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In the present sample, the scale’s internal consistency was low (α = 0.50). However, removing Item 5 (“Our society still prevents the satisfaction of important human needs”) increased the scale’s reliability from 0.50 to 0.60. Still, we decided not to remove the item before conducting our analyses to keep as many of the original items as possible.

2.4 Plan of analysis

As we disclosed in our preregistration, only participants who filled out more than 50% of the questionnaire were included in the data set we analyzed. In addition, participants who took less than five minutes to complete the survey were excluded, as they might not have read and answered the questions thoroughly. Because missings occurred rarely (i.e., < 3%), no data imputation was applied. Instead, missings were treated by listwise deletion in SPSS. No outliers were removed to avoid artificially boosting any effects and thus preserve the sample’s natural variations.

We began by extracting descriptive statistics for our sample. We then conducted bivariate analyses to check for gender differences (t tests) and correlations between attitudes and the background variables.

Finally, we conducted multiple regression analyses to verify our hypotheses and to check which predictor variables were significantly related to the preservice teachers’ attitudes when controlling for the other predictor and background variables. For our main regression analyses, a priori power analysis using the G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7) revealed that for a multiple regression analysis with a desired medium effect size, an alpha error probability of 0.05, a power of 0.95, and seven predictor variables, the recommended total sample size was 153. We included only seven predictor variables because, for the regression analysis, the hypermasculinity and hyperfemininity scales needed to be combined into one hypergendering scale. With a total of 138 participants who provided valid data, we missed the targeted sample size by 9.8%.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive and bivariate results

Regarding sexual orientation, most participating women indicated that they were attracted to men only (76.8%), with an additional 19.2% tending to be attracted to men. Only two women (2%) indicated that they were attracted to both genders equally, with another two women (2%) being more attracted to women. On the other hand, most men indicated that they were attracted to women only (89.7%). Only two men (5.1%) indicated being exclusively attracted to men, with another two (5.1%) indicating a tendency to be attracted to men.

Regarding attitudes toward LGB students as assessed with the composite questionnaires, t tests did not identify significant gender differences for any of the three groups (i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual students). Furthermore, when comparing the means for participating men and women on the feeling thermometers, there were no significant differences for any of the three groups either. Women tended to have weaker hypergendering tendencies, the mean difference just missing statistical significance, t(130) = − 1.946, p = .054, Cohen’s d = − 0.384. There were no significant mean differences between the participants’ gender in their levels of religiosity. Women had significantly lower scores on right-wing conservatism than men, t(136) = − 3.633, p < .001, Cohen’s d = − 0.687.

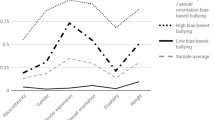

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for all variables, as well as bivariate correlations. Overall, the preservice teachers had positive attitudes toward LGB students, as their mean ratings were significantly higher than the theoretical mean of 3.5 for the questionnaires (p < .001) and 50 for the feeling thermometers (p < .001). The different measures of attitudes toward LGB students were positively correlated with each other with correlations ranging from .33 to .48, indicating that positive attitudes measured by the questionnaires were reflected by positive attitudes measured by the feeling thermometers. According to Cohen’s interpretation of Pearson correlation coefficients (Cohen, 1988), these correlations can be considered moderate. Furthermore, within measurement instruments, the attitudes toward LGB students were strongly intercorrelated (most correlations were above .90), indicating that positive attitudes toward one LGB group reflected positive attitudes toward the other groups. Regarding contact with LGB people, having a close or extended friendship with an LGB person was associated with more positive attitudes toward LGB students (r ranging from .17 to .28). Surprisingly, frequent contact with an LGB family member was not significantly correlated with positive attitudes toward LGB students. In addition, the corresponding correlation coefficients were small and did not exceed .10. Regarding the hypergendering variables, there were significant negative correlations for both hypermasculinity and hyperfemininity with attitudes toward LGB students measured with our questionnaires, indicating that less adherence to gender-specific stereotypes was associated with more positive attitudes toward LGB students. The correlations were stronger for hypermasculinity (r ranging from − .39 to − .44) than for hyperfemininity (r ranging from − .23 to − .25). However, these findings did not hold for the feeling thermometers. Participants’ age and gender were not associated with attitudes toward LGB students. Interestingly, sexual orientation was significantly positively associated with LGB attitudes (r ranging from .19 to .26), indicating that straight preservice teachers tended to hold more positive attitudes toward LGB students than their lesbian or gay peers. Religiosity was significantly negatively correlated with all questionnaire measures (r ranging from − .22 to − .26), indicating that less religious preservice teachers tended to have more positive attitudes toward LGB students. Interestingly, the correlation table also shows that less religious people tend to have more social contact with LGB people in their families as well as in their close and extended friendships. Finally, the negative correlation between right-wing conservatism and LGB attitudes was rather small and was not statistically significant in some cases (r = − .18 for significant correlations), which may be a consequence of the low reliability of the conservatism scale. Correlations between the hypergendering variables as well as between the hypergendering variables and gender were not available because no participants responded to both questionnaires, as only men responded to the hypermasculinity scale and only women responded to the hyperfemininity scale.

3.2 Multiple regression analyses

Three multiple regressions were computed, one for each LGB attitude composite measure. There were no signs of violation regarding the statistical assumptions of the data that had to be met to conduct a multiple linear regression, except for some indications of multicollinearity for the social contact variables “close friends” and “extended friends” (VIFs between 1.9 and 2.8). Even though these values could be considered negligible, we decided to combine the two variables into one variable representing social contact with LGB individuals in the participants’ network of friends to strengthen the regression model. Results of the multiple regression analyses can be found in Table 2. All three regression models significantly predicted preservice teachers’ attitudes toward LGB students. The most variance was explained in the model for attitudes toward lesbian students (R2 = 0.267), followed by bisexual (R2 = 0.256) and gay (R2 = 0.245) students. Social contact significantly predicted attitude scores in our questionnaire in light of all other variables; only family contact was not a significant predictor of attitudes toward bisexual students (p = .106). Whereas contact with LGB people within friend circles was related to more positive attitudes toward LGB students, surprisingly, frequent contact with LGB family members was related to more negative attitudes. Hypergendering significantly predicted attitudes in all three regression analyses, with less hypergendering tendencies being related to more positive attitudes. Age and gender were not significant predictors of attitudes when all the other variables were held constant, but the negative regression coefficients hinted that younger and female preservice teachers had more positive attitudes. Furthermore, sexual orientation also predicted the preservice teachers’ attitudes in all three regression models, the positive regression coefficients indicating that heterosexuality was related to more positive attitudes. Religiosity significantly predicted attitudes toward lesbian and bisexual students, such that less religious preservice teachers had more positive attitudes, whereas the regression coefficient for attitudes toward gay students approached significance (p = .059). Our measure of right-wing conservatism did not predict attitudes in either regression model.

To check which predictor explained the most variance in the regression model, we computed further multiple regression analyses (again, one analysis for each sexual orientation) with stepwise integration of three blocks of predictors. Block 1 included the social contact variables, Block 2 represented the hypergendering measures, and Block 3 included the demographic and individual variables (i.e., age, gender, sexual orientation, religiosity, and conservatism). Results of the stepwise regression analyses are presented in Table 3 and indicate that all three blocks of predictors were able to reliably predict attitude scores for all three sexual orientations. In general, this finding means that every group of predictors explained a significant proportion of the variance in the overall regression model presented above. For gay and lesbian attitudes, social contact was the strongest predictor, followed by individual and demographic variables and hypergendering tendencies. However, for attitudes toward bisexual students, the strongest predictor explaining the most variance was the block of individual and demographic variables, followed by social contact and hypergendering tendencies.

Finally, to directly compare our results to Gegenfurtner’s (2021) and Gegenfurtner et al.’s (2023) results, we conducted three more regression analyses for predicting preservice teachers’ attitudes measured with the 101-point feeling thermometer scale. The results of these multiple regression analyses can be found in Table 4. In fact, none of the three regression models were able to reliably predict attitudes on the feeling thermometers, as indicated by the nonsignificant F-values. Furthermore, the models explained much less variance (not exceeding 10%) than the models predicting the questionnaire scores (about 25% for all three models). Most predictors did not even approach statistical significance. The predictors closest to reaching statistical significance were contact with friends (close and extended) for attitudes toward lesbian students (p = .113), gender for attitudes toward gay students (p = .093), and once again contact with friends (close and extended) for attitudes toward bisexual students (p = .188).

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary and discussion of findings

In this preregistered study, we investigated preservice teachers’ attitudes toward LGB students in Luxembourgish teacher education programs and aimed to identify the attitudes’ correlates. At the beginning of this paper, we postulated different hypotheses that were based on previous attitude studies. Table 5 shows whether or not each hypothesis was supported by the data.

The support for Hypothesis 1 is in line with most research investigating (preservice) teachers’ attitudes toward LGB students (e.g., Gegenfurtner et al., 2023). The questionnaire measures worked fine for our sample, but no other published studies have used this questionnaire yet, so we cannot compare our sample’s results with other samples. Regarding the feeling thermometer scores, our sample of Luxembourgish preservice teachers had mean scores of about 72 for all three categories, findings that are consistent with the mean feeling thermometer scores that Gegenfurtner et al. (2023) generated in their sample of German preservice teachers. These numbers seem very promising, as Norton and Herek’s (2013) sample of heterosexual U.S. adults produced mean feeling thermometer scores for LGB people ranging from 34 to 42. These rather large differences may stem from differences in the samples, as Norton and Herek surveyed a much larger sample of more than 2,000 participants that was not limited to students. Besides these methodological differences, the difference in attitudes could also be due to a recent tendency toward declining homophobia in society (Diefendorf & Bridges, 2020).

The support for Hypothesis 2 serves as an indicator that intergroup contact affects attitudes toward sexual minority groups in a positive way and is in line with findings from a number of previous studies (Baiocco et al., 2020; Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Grigoropoulos, 2022; Klocke et al., 2019; Zotti et al., 2019). This finding is particularly important because an increasing number of young people identify as LGB (Jones, 2022), which promotes intergroup contact in a natural way (i.e., as more and more people identify as LGB, the natural consequence is that it becomes more likely to get to know an LGB person). Ultimately, expressed simplistically, LGB people disclosing their sexual orientation may promote other people’s benevolent attitudes toward these sexual minority groups. However, and surprisingly, this positive effect applies only when contact occurs in the context of friendships and not between family members, an observation Gegenfurtner et al. (2023) also made in their study. In our sample, having frequent contact with an LGB family member was even associated with negative attitudes toward lesbian women and gay men. To explain this surprising association, one could speculate that it may stem from the fact that common interests are usually shared within friendships, whereas within family relationships, common interests do not necessarily occur. This phenomenon implies that, for instance, the “weird and unpopular uncle” who happens to be gay may be responsible for negative attitudes in one person, whereas the nice lesbian couple living next door with lots of common interests may be responsible for positive attitudes in another person. If such effects are indeed occurring, then the positive attitudes are not necessarily due to pure intergroup contact. Accordingly, maintaining friendships with LGB people may play a bigger role than pure intergroup contact in fostering benevolent attitudes toward LGB people in general.

In finding support for Hypothesis 3, we identified another correlate of preservice teachers’ attitudes toward LGB students, namely, hypergendering. Whereas previous research found that hypergendering tendencies were associated with higher prejudice against LGBT people in different samples, such as in U.S. university students (e.g., Caballero, 2013; Hackimer et al., 2021) and in Western society in general (Bettinsoli et al., 2020), we were the first research team, to our knowledge, to find this relationship in preservice teachers. This finding is alarming, as traditional gender roles remain prevalent in Germany, even among young adults, and especially among young men. In a large survey study published by Plan International Germany, the authors reported, for instance, that 50% of surveyed men would oppose entering a relationship with a woman who had many sexual partners in the past, that 33% of surveyed men find it acceptable to slap their partner once in a while, and that 52% of surveyed men view it as their responsibility to make enough money and think their partner should take care of the household (Hofmann et al., 2023). As we already discussed, this finding that hypergendering is related to negative attitudes toward LGB students in preservice teachers could be explained by the fact that LGB students violate preservice teachers’ rigid gender belief systems, causing negative attitudes to arise (Whitley, 2001). One could speculate that preservice teachers’ gender belief systems have grown rigid due to cultural influences, as traditional gender role beliefs are deeply rooted in society and can be transmitted via family, peer, or specific media content. Considering intergroup contact theory, one could also speculate that preservice teachers with rigid gender belief systems tend to avoid contact with LGB people (as they perceive them negatively). Consequently, such teachers end up with a lack of exposure to and a lack of familiarity with LGB people, which leaves them without any opportunity to change their stereotypical beliefs. Our results partially supported this claim, as we found that hyperfemininity was significantly negatively associated with LGB social contact (r ranging from − 0.20 to − 0.32), but hypermasculinity was not.

Regarding background variables, we found that age (Hypothesis 4a) and gender (Hypothesis 4b) did not reliably predict preservice teachers’ attitudes. The lack of support for Hypothesis 4a conflicts with previous research (Andersen & Fetner, 2008; Baiocco et al., 2020; Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Hall & Rodgers, 2019) and may have occurred due to the small number of participants in the extreme age groups, as the vast majority (79%) of our participants were between 21 and 26 years of age. A more balanced distribution of the age categories may have revealed a statistically significant result. The lack of support for Hypothesis 4b corresponds to findings from previous research (Mudrey & Medina-Adams, 2006; Wyatt et al., 2008). At the same time, rejecting gender as a reliable predictor of teachers’ attitudes toward LGB students contradicts other research (Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Heras-Sevilla & Ortega-Sánchez, 2020) and thus suggests inconsistency in the role of teacher gender as a correlate of teacher attitudes. As our sample consisted mostly of women (71.7%), the results must be interpreted carefully, as another sample with a more balanced gender distribution may provide different findings. Thus, we were unable to find support for the assumption brought up by Vieira de Figueiredo and Pereira (2021) that women tend to be more tolerant of gender role transgressions and consequently tend to have less homonegative and binegative attitudes than men.

Our lack of support for Hypothesis 4c is in line with the findings from Hall and Rodgers (2019) but contradicts other studies on teacher attitudes (Foy & Hodge, 2016; Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Stucky et al., 2020). Surprisingly, our results supported the opposite effect, as straight sexual orientation reliably predicted positive attitudes toward LGB students in our sample. Again, this finding hints that there are inconsistencies in the findings on whether teachers’ sexual orientation is a correlate of LGB prejudice. It remains unclear whether this effect stems from methodological issues—as only six of 138 participants indicated that they were gay or lesbian and only two that they were bisexual, skewing this variable substantially, or whether there is a deeper explanation. For instance, we could speculate that the few gay or lesbian participants had elevated levels of internalized homonegativity. Internalized homonegativity “refers to the process whereby lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) persons internalize societal messages toward gender and sex—often unconsciously—as part of their self-image,” which can result in “negative feelings toward oneself when a person recognizes his or her own homosexuality or bisexuality” (Berg et al., 2016, p. 541). In this way, LGB preservice teachers may view LGB students more negatively even though they may share the same marginalization experiences.

Finally, the support we found for Hypothesis 5a is in line with most previous research (Baiocco et al., 2020; Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Hall & Rodgers, 2019; Page, 2017; Stucky et al., 2020). Even though religious values have drastically dropped in Luxembourg over the last decade (Allegrezza, 2023), they were still reliably associated with negative LGB attitudes in the preservice teachers in this study. Many religions have teachings that could be interpretated as viewing homosexuality as immoral or sinful without explicitly teaching hatred toward sexual minority groups. For instance, in early Islamic culture, “male-male sexual relations apparently were ridiculed, but not formally sanctioned. Poetry celebrated heterosexuality, while proverbs and ritual insults stigmatized men ‘acting like women’ by being sexually receptive to other men” (Roscoe & Murray, 1997, p. 307). Individuals who strongly adhere to interpretations condemning homosexuality may internalize this implicit homonegativity and consequently develop negative attitudes toward LGB people. Regarding Hypothesis 5b, and contrary to most previous research, right-wing conservatism could not reliably predict negative attitudes toward LGB students in preservice teachers (Baiocco et al., 2020; Foy & Hodge, 2016; Gegenfurtner et al., 2023; Hall & Rodgers, 2019; Heras-Sevilla & Ortega-Sánchez, 2020). In our reliability analysis, we found the internal consistency of the right-wing conservatism scale to be quite low in our sample, which could be one of the reasons why this predictor could not be classified as reliable in the regression analyses. Similar to hypergendering tendencies (and maybe even religiosity), one might argue that the construct of right-wing conservatism includes traditional values and social norms. Such a tendency could partially be observed in our results, as we found a significant moderate correlation between right-wing conservatism and hyperfemininity (i.e., traditional female gender role beliefs) despite the low reliability of the conservatism scale. Again, adhering to these traditional values may conflict with the acceptance of nonheterosexual orientations, leading right-wing conservative individuals to form negative attitudes toward LGB people.

The aim of the present study was to replicate Gegenfurtner’s (2021) findings in Luxembourgish teacher education and address several limitations. In line with his results, we also found overall positive attitudes and supported the claim that intergroup contact and religiosity are important correlates of teacher attitudes. Contrary to Gegenfurtner (2021), we identified sexual orientation as an important predictor, but we did not find gender differences. We also did not find that right-wing conservatism reliably predicted attitudes. We were able to resolve Gegenfurtner’s issue regarding the use of the 101-point, one-dimensional feeling thermometer and provided evidence that the combination of the ELIAS questionnaire with the ATLG-5 scales is a reliable tool for assessing attitudes with a continuous measure. We were also able to assess most background variables on a continuum (and not dichotomously), but the internal consistency of our right-wing conservatism assessment was quite low. Choosing to employ an alternative assessment tool or to use the full 18 items from Cloetta’s (1997) Machiavellianism-Conservatism scale’s conservatism subscale may have raised the reliability of our right-wing conservatism assessment.

4.2 Limitations

Several limitations of our study are worth noting. First, we used convenience sampling. Similar to Gegenfurtner’s (2021) study, it may be possible that preservice teachers with stronger levels of prejudice against LGB students decided not to take part in our study. Therefore, it may be possible that our results overestimate the true scores from the attitude questionnaires. Second, the sample size and composition represent limitations. We were unable to recruit enough participants to reach the number of participants identified by an a priori power analysis, and older, male, as well as homosexual and bisexual preservice teachers were underrepresented in our sample. However, as only about 400 preservice teachers are enrolled in the University of Luxembourg’s teacher education program, we were able to recruit about one third of all eligible participants. Third, the fact that we combined the items from the ATLG-5 and those from Gegenfurtner and colleagues’ ELIAS project diminishes the comparability of our results with results from future studies emerging from the ELIAS project. In this regard, we note again that the ATLG-5 captures rather extreme attitudes toward LGB people, which might bias responses. A further methodological limitation arising from the combination of the ELIAS and ATLG-5 items is that it appears questionable whether all subscales capture attitudes in the core meaning of Eagly and Chaiken (2007). While according to their definition, attitudes are defined as psychological tendencies expressed through evaluating students with approval or disapproval, in our study, attitudes were understood more broadly. Specifically, we operationalized attitudes as a combination of teaching specific attitudinal values and beliefs targeting LGB students, such as enthusiasm and perceived self-efficacy to work with LGB students, as well as stereotypes and tolerance toward them. Against this background, some unexpected findings on attitude predictors may also have resulted from constructing our composite scales. For instance (we are speculating here), it could have been the case that women indeed had fewer stereotypes and more tolerance toward LGB students (as claimed in Hypothesis 4b), but this did not come out in the regression analysis because men endorsed the teacher self-efficacy items to a greater extent. Therefore, future research on the ELIAS subscales should apply a more differentiated analysis. Fourth, the feeling thermometer approach did not work for our sample as expected. Gegenfurtner (2021) and Gegenfurtner et al. (2023) also addressed the feeling thermometer as a limitation. Whereas we also believe that this approach is parsimonious, intuitive, and cost-effective, it does not seem well-suited for assessing preservice teachers’ attitudes toward LGB students. In particular, it is problematic that high values on the feeling thermometer do not represent a high sense of equality but rather a preference for LGB students over non-LGB students (in contrast to low scores, which represent the disapproval of LGB students), thus rendering this variable difficult to subject to correlational analyses. That is, because the anchor of 50 (the midpoint) represents the theoretical mean of the feeling thermometer (and thus represents equal attitudes toward minority and nonminority students), in rating minority students either higher or lower than 50, preservice teachers are admitting that they view minority students more positively or negatively than they view nonminority students. Such ratings would contradict the basic concept of equality in education. Apart from this issue, as with all self-report measures, all the attitude measures in our study are prone to social desirability effects. Preservice teachers may be aware of social norms and, consequently, they may want to treat and evaluate nonminority and LGB students equally, even though their attitudes toward LGB students may be negative. Overall, such a tendency would create more positive attitude measures. To tackle this issue, future research could use other attitude assessment tools (e.g., implicit association tests) and investigate whether preservice teachers’ scores differ significantly between the two measures. Fifth, we must note that we used two independent scales (one for hyperfemininity and one for hypermasculinity) to assess hypergendering in our study. Consequently, combining the two assessments into one scale (as we did for the multiple regression analysis) includes the limitation that measure and gender were confounded. We therefore suggest that future researchers use a gender-neutral assessment tool to measure this construct, such as the Hypergender Ideology Scale (HGIS) put forward by Hamburger et al. (1996).

4.3 Implications and directions for future research

By identifying positive attitudes toward LGB students, our results suggest that Luxembourgish preservice teachers’ attitudes toward all three of the sexual orientations we investigated are at the same level. This result means that they might not be prejudiced against any particular sexual orientation and may view homosexual and bisexual students in the same light as their straight peers, but this assumption needs to be investigated in direct comparative research. Future research could also investigate whether this finding holds for different gender identities, such as cisgender, transgender, or gender-queer students. Whereas sexual orientation is all about who the students are attracted to, gender identity refers to who the students really are and to the gender with which they self-identify. It may be important to investigate self-identification, as transgender and nonbinary students were previously found to report significantly more psychosocial burdens (e.g., lower life satisfaction, more loneliness, mental health problems) than their cisgender peers (Anderssen et al., 2020).

Our results also have implications for teacher education. In finding evidence for intergroup contact theory, teacher education programs should bring LGB students’ needs to the forefront or even promote contact between preservice teachers and LGB students, for instance, by including LGB students or LGBTQ+ experts’ views in the seminars (Gegenfurtner et al., 2023). These guest speakers can share their perspectives and experiences to foster dialogue and understanding among preservice teachers. Furthermore, teacher education programs could offer LGBTQ+ awareness workshops in which preservice teachers learn to create inclusive and affirming classroom environments. In addition, teacher education programs could design collaborative projects in which preservice teachers cooperate with organizations that support the LGBTQ+ community. For instance, they could develop LGBTQ+-inclusive educational resources or design interventions to raise awareness in active teachers. Future research could develop and test such interventions and could analyze intergroup contact theory in more detail, for instance, by investigating whether the quality or the quantity (or both) of the intergroup contact is responsible for positive attitudes. Further, research could focus on explaining why there seem to be differences in effects between intergroup contact in relationships with family members versus in friendships to fully understand the mechanisms behind preservice teachers’ attitudes toward LGB students.

Similarly, as adhering to traditional gender stereotypes may be responsible for prejudice against LGB students in preservice teachers, teacher education programs might raise awareness of this issue. For example, teacher education seminars could cover topics, such as the Pygmalion effect mentioned above, which can be perceived as a possible consequence of hypergendering. Additionally, or alternatively, teacher education seminars could teach preservice teachers how to rid themselves of stereotypes. For instance, Devine et al. (2012) developed a promising intervention program that significantly reduced ethnic prejudice in U.S. psychology students. The intervention program utilizes techniques, such as stereotype replacement (i.e., consciously identifying one’s own biased answers and actively trying to find an unbiased alternative response) or perspective taking (i.e., taking the perspective in the first person as a stereotyped group member), and may also be redesigned in the future to reduce sexual prejudice. As we are not aware of any studies that have investigated the Pygmalion effect for sexual orientation or sexual identity minorities, future research could aim to identify whether (preservice) teachers’ prejudice toward students who belong to these minorities leads to biases in teacher expectations and thus to a Pygmalion effect that negatively influences the students’ academic success or other important academic variables.

Notes

Results from exploratory principal component analyses (with varimax rotation) yielded a three-factor solution for all three scales (i.e., attitudes towards lesbian, gay, and bisexual students, see Appendix C). We interpreted these solutions as reflecting a stereotype factor and a teacher self-efficacy factor, based on the ELIAS items. However, both factors may also reflect more generally a methodological component, as the former factor was mainly based on the reversed coded ELIAS items, hence, reflecting LGB disapproval in a broad sense, whereas the latter factor represented items reflecting LGB approval. This interpretation is also supported by the finding that the two enthusiasm items also loaded on this factor. The third factor represented the items from the ATLG-5 scale, which we interpreted as LGB-tolerance. Using Mplus, a confirmatory factor analyses indicated that a higher-order factor model, specifying a general attitude factor that underlies the ELIAS subscales (i.e., enthusiasm, self-efficacy, and stereotypes) and the ATLG-5 scale as four separate lower-order factors, yielded a good fit— given the breadth of the measures included in the questionnaire—for attitudes toward lesbian and gay students (CFI = .90/.91; TLI = .88/89; RMSEA = .12/.12; SRMR = .10/.13, respectively). Yet, the fit was considerably poorer for bisexual students (CFI = .76; TLI = .72; RMSEA = .21; SRMR = .12). We suspect that this was mainly due to a poor item selectivity for the positively worded items of the ATLG-5 scale in this case.

References

Ahrold, T. K., & Meston, C. M. (2010). Ethnic differences in sexual attitudes of U.S. college students: Gender, acculturation, and religiosity factors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(1), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9406-1

Allegrezza, S. (2023). Net recul des pratiques religieuses et montée des spiritualités alternatives au Luxembourg [A sharp decline in religious practices and rise of alternative spiritualities in Luxembourg] (No. 03/23; Regards). Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg (STATEC). https://statistiques.public.lu/fr/publications/series/regards/2023/regards-03-23.html

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

Almeida, J., Johnson, R. M., Corliss, H. L., Molnar, B. E., & Azrael, D. (2009). Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 1001–1014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9

Andersen, R., & Fetner, T. (2008). Cohort differences in tolerance of homosexuality: Attitudinal change in Canada and the United States, 1981–2000. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(2), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn017

Anderssen, N., Sivertsen, B., Lønning, K. J., & Malterud, K. (2020). Life satisfaction and mental health among transgender students in Norway. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8228-5

Baiocco, R., Rosati, F., Pistella, J., Salvati, M., Carone, N., Ioverno, S., & Laghi, F. (2020). Attitudes and beliefs of Italian educators and teachers regarding children raised by same-sex parents. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 17(2), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00386-0

Berg, R. C., Munthe-Kaas, H. M., & Ross, M. W. (2016). Internalized homonegativity: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(4), 541–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1083788

Bettinsoli, M. L., Suppes, A., & Napier, J. L. (2020). Predictors of attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women in 23 countries. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(5), 697–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619887785

Birkett, M., Russell, S. T., & Corliss, H. L. (2014). Sexual-orientation disparities in school: The mediational role of indicators of victimization in achievement and truancy because of feeling unsafe. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1124–1128. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301785

Caballero, N. (2013). Attitudes and beliefs towards LGBTQ community in a college campus [Master’s thesis, California State University]. Sacramento. https://csu-csus.esploro.exlibrisgroup.com/esploro/outputs/99257831282101671?skipUsageReporting=true

Chen, E. E., & Chang, J.-H. (2020). Investigating implicit and explicit attitudes toward sexual minorities in Taiwan. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(2), 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000362

Cloetta, B. (1997). Machiavellismus-Konservatismus [Machiavellianism-conservatism]. Zusammenstellung Sozialwissenschaftlicher Items Und Skalen (ZIS). https://doi.org/10.6102/ZIS82

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. L. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1267–1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003

Diefendorf, S., & Bridges, T. (2020). On the enduring relationship between masculinity and homophobia. Sexualities, 23(7), 1264–1284. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460719876843

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (2007). The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Social Cognition, 25(5), 582–602. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2007.25.5.582

Estévez, E., Musitu, G., & Herrero, J. (2005). The influence of violent behavior and victimization at school on psychological distress: The role of parents and teachers. Adolescence, 40, 183–196.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2014). European Union lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender survey: main results. Publications Office. https://doi.org/10.2811/37969

Foy, J. K., & Hodge, S. (2016). Preparing educators for a diverse world: Understanding sexual prejudice among pre-service teachers. Prairie Journal of Educational Research, 1(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4148/2373-0994.1005

Gegenfurtner, A. (2021). Pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward transgender students: Associations with social contact, religiosity, political preference, sexual orientation, and teacher gender. International Journal of Educational Research, 110, 101887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101887

Gegenfurtner, A., & Gebhardt, M. (2017). Sexuality education including lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) issues in schools. Educational Research Review, 22, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.10.002

Gegenfurtner, A., Hartinger, A., Gabel, S., Neubauer, J., Keskin, Ö., & Dresel, M. (2023). Teacher attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and bisexual students: Evidence for intergroup contact theory and secondary transfer effects. Social Psychology of Education, 26(2), 509–532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-022-09756-w

Gentrup, S., Lorenz, G., Kristen, C., & Kogan, I. (2020). Self-fulfilling prophecies in the classroom: Teacher expectations, teacher feedback and student achievement. Learning and Instruction, 66, 101296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101296

Glikman, A., & Elkayam, T. S. (2019). Addressing the issue of sexual orientation in the classroom—attitudes of Israeli education students. Journal of LGBT Youth, 16(1), 38–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2018.1526732

Glotfelter, M. A., & Anderson, V. N. (2017). Relationships between gender self-esteem, sexual prejudice, and trans prejudice in cisgender heterosexual college students. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(2), 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1274932

Goldstein-Schultz, M. (2022). Teachers’ experiences with LGBTQ+ issues in secondary schools: A mixed methods study. Community Health Equity Research & Policy, 42(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684X20972651

Górska, P., Van Zomeren, M., & Bilewicz, M. (2017). Intergroup contact as the missing link between LGB rights and sexual prejudice. Social Psychology, 48(6), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000313

Grigoropoulos, I. (2022). Greek high school teachers’ homonegative attitudes towards same-sex parent families. Sexuality & Culture, 26(3), 1132–1147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09935-5

Hachfeld, A., Schroeder, S., Anders, Y., Hahn, A., & Kunter, M. (2012). Multikulturelle Überzeugungen: Herkunft oder Überzeugung? Welche Rolle spielen der Migrationshintergrund und multikulturelle Überzeugungen für das Unterrichten von Kindern mit Migrationshintergrund? [Multicultural convictions: Origin or conviction? What role do migrant backgrounds and multicultural beliefs play in teaching children with migrant backgrounds?]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 26(2), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652/a000064

Hackimer, L., Chen, C.Y.-C., & Verkuilen, J. (2021). Individual factors and cisgender college students’ attitudes and behaviors toward transgender individuals. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(6), 2023–2039. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22546

Hall, W. J., & Rodgers, G. K. (2019). Teachers’ attitudes toward homosexuality and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer community in the United States. Social Psychology of Education, 22(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9463-9

Hamburger, M. E., Hogben, M., McGowan, S., & Dawson, L. J. (1996). Assessing hypergender ideologies: Development and initial validation of a gender-neutral measure of adherence to extreme gender-role beliefs. Journal of Research in Personality, 30(2), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1996.0011

Harbaugh, E., & Lindsey, E. W. (2015). Attitudes toward homosexuality among young adults: Connections to gender role identity, gender-typed activities, and religiosity. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(8), 1098–1125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1021635

Heras-Sevilla, D., & Ortega-Sánchez, D. (2020). Evaluation of sexist and prejudiced attitudes toward homosexuality in Spanish future teachers: Analysis of related variables. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 572553. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572553

Herek, G. M. (2009). Sexual stigma and sexual prejudice in the United States: A conceptual framework. In D. A. Hope (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities (Vol. 54, pp. 65–111). Springer.

Herek, G. M., & McLemore, K. (2011). Attitudes toward lesbians and gay men scale. In T. D. Fisher, C. Davis, W. Yarber, & S. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (3rd ed., pp. 415–417). Routledge.