Abstract

Choosing a field of study (study major) is challenging for prospective students. However, little research has examined factors measured prior to enrollment to predict motivation and well-being in a specific study major. Based on literature on affective forecasting and person-environment fit, prospective students’ well-being forecast could be such a factor. However, affective forecasts are often biased by individuals’ inaccurate theories about what makes them happy and their misconstrual of future situations. Thus, we hypothesize that subjective and objective interest-major fit forecasts improve predictions as these factors are based on a well-founded theory (person-environment fit theory) and objective interest-major fit forecasts are additionally based on a more accurate construal of the future situation (expert estimates of a study major). We tested these hypotheses in a longitudinal field study. Over 2 years, more than 4000 prospective students were asked for their well-being forecast and subjective interest-major fit forecast before using an online-self-assessment to assess their objective interest-major fit forecast. Of these prospective students, 234 subsequently entered the psychology major and took part in a survey about their motivation and well-being in their study major. As hypothesized, higher well-being forecasts predicted higher motivation, more positive affect, and higher satisfaction in the respective major. Beyond that, higher subjective interest-major fit forecasts predicted higher motivation, less negative affect, and higher satisfaction, while objective interest-major fit forecasts incrementally predicted higher motivation, more positive affect, and higher satisfaction. We discuss theoretical implications for affective forecasting and person-environment fit theory and practical implications for study orientation and guidance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The choice of a field of study (study major) is the first step for students along the path of higher education and represents an important life choice (Schindler & Tomasik, 2010). To make a good choice, prospective students need to know not only how well they will do in a particular major, but also how motivated and satisfied they will be. The difficulty of this task is shown by about 30% of students changing their major (NCES, 2018), and more than 20% of students ending up not being satisfied with their studies (Wong & Chapman, 2023). While some higher education systems offer orientation phases for students to explore various majors and find out how much they like different majors, other education systems (e.g., the German system) do not have such a phase (Messerer, Karst & Janke, 2023). Instead, they usually expect prospective students to choose a study major before entering university and stay with it as dropping out or changing the study major comes with costs for the individual and the organization and therefore is often seen as an event that should be avoided (Behr et al., 2020; Soppe et al., 2019). Thus, especially in education systems without an orientation phase it is important to predict how successful prospective students will be in a specific study major even before they enter university.

There is a broad body of literature focusing on the prediction of objective study success outcomes, for example predicting academic performance or dropout using high school grade point average (e.g., Geiser & Santelices, 2007), or tests in the selection procedure (e.g., trial-studying tests, Niessen et al., 2016). However, several models of study success (e.g., Bean & Metzner, 1985; Heinze, 2018) not only include objective outcomes such as grades and dropout as indicators of students’ success but also subjective outcomes such as their motivation and satisfaction. Regarding the prediction of subjective outcomes there is less research, and the existing research focuses mainly on factors predicting the intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being of students independent of the respective study major (e.g., Respondek et al., 2017; Steel et al., 2008). Little research has focused on factors that target a specific study major and thus have the potential to predict students’ intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being within a specific study major (e.g., Etzel & Nagy, 2016) and to the best of our knowledge there is no research that explores major-specific predictors for intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being (e.g., positive affect, negative affect and satisfaction) in a study major measured even before entering university.

We aim to fill this gap by implementing an ecologically valid field design accompanying prospective students in their transition to university. Drawing from theories of affective forecasting (e.g., Wilson & Gilbert, 2003) our first goal is to examine to which extent prospective students’ forecast of their subjective well-being within a specific study major (well-being forecast) can predict their later intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in the respective study major. Combining theories of biases in affective forecasting (e.g., Wilson & Gilbert, 2003) with the person-environment fit theory (e.g., Le et al., 2014), our second goal is to test whether prospective students’ forecast of their interest-major fit (subjective interest-major fit forecast) improves the prediction of their later intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in the respective study major. Building on this, our third goal is to examine whether prospective students’ forecast of their interest in specific contents which represent a valid construal of the respective study major (objective interest-major fit forecast) can further improve the prediction. Our research will shed light on whether prospective students need more support in predicting their major-specific intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being before entering university and how this support could look like to ensure successful decisions to pursue a particular study major.

1.1 Interest-major fit—explaining students’ major-specific subjective well-being

A large number of studies has already identified many factors predicting the intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being of students within their studies, including personality traits (e.g., Clark & Schroth, 2010; Sood et al., 2012) or study circumstances such as perceived demands like time pressure (e.g., Lesener et al., 2020), perceived resources like social support (e.g., Mokgele & Rothmann, 2014) and perceived academic control (e.g., Respondek et al., 2017). However, when it comes to choosing one study major among many, it is most relevant to know which factors that target a specific study major determine intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in a specific study major. Based on person-environment fit theory a fit between a person’s characteristics and the characteristics of the environment leads to more success (e.g., Bretz & Judge, 1994; Cable & DeRue, 2002; Edwards & Shipp, 2007; Le et al., 2014). In the university context the fit between students’ interests (person) and study contents (environment) is referred to as interest-major fit (person-environment fit) and has proven to be a predictor for study satisfaction and dropout intention (Etzel & Nagy, 2016). However, these research findings on interest-major fit stem from students who had already chosen their major and were in the middle of their studies. Thus, it remains unclear whether variables already measured before entering a study major can predict later intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being within this specific major and thus could be useful to guide prospective students’ decision-making process.

1.2 Well-being forecast—influenced by biases

When making decisions people are guided by their affective forecasting, their anticipation about how they will feel in a future situation (Conner et al., 2015; Wilson & Gilbert, 2003). The affective forecasting literature shows, in a wide variety of contexts, that this approach is reasonable as people can to some extent forecast their own subjective well-being before they have experienced the respective situation (e.g., Gilbert et al., 1998). We assume that these findings also hold in the context of choosing a study major because prospective students had a lifetime of collecting information about themselves in different learning environments. Because of these previous experiences prospective students should be able to forecast their intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in a study major to some extent before they enter university. However, more importantly, the affective forecasting literature also shows that these forecasts are far from perfectly accurate and identifies several biases that could explain forecasts’ deviations from reality, including inaccurate theories and misconstrual (for an overview, see Gilbert et al., 1998; Wilson & Gilbert, 2003). Those biases can help to better understand why prospective students’ well-being forecast could deviate from later reality. This better understanding in turn can help to identify important factors that could improve the prediction of later intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in a study major.

1.3 Subjective interest-major fit forecast—reducing inaccurate theories

Formed by culture or personal experiences, individuals may have very different theories about the emotional consequences of specific events or actions and some of these are partly wrong, for example the assumption that money is the key to happiness (Aknin et al., 2009; Wilson & Gilbert, 2003). Affective forecasts based on those theories are also likely to be wrong to some extent (Wilson & Gilbert, 2003), for example, choosing a study major for materialistic reasons is not related to more study satisfaction (Janke et al., 2021). If one reason for prospective students' biased well-being forecasts is their use of inaccurate theories, then using a scientifically proven theory should help them make better forecasts. In the context of predicting study satisfaction such a theory would be the person-environment fit theory (Cable & DeRue, 2002; Edwards & Shipp, 2007), based on which it can be assumed that higher interest-major fit predicts higher study satisfaction (Etzel & Nagy, 2016). Following this rationale, subjective interest-major fit forecast (assessed by simply asking prospective students to forecast their interest-major fit) should improve the prediction of later subjective well-being because it directs prospective students’ forecast to an empirically proven cause of later subjective well-being.

1.4 Objective interest-major fit forecast—reducing inaccurate theories and misconstrual

To forecast their fit to a specific study major, prospective students not only need a lot of insight about themselves but also a lot of information about the respective study major in question. In some education systems students have an orientation phase to get to know different study majors (Messerer, Karst & Janke, 2023) or take part in a curriculum-sampling test during the selection procedure which contains fidelity simulations of (parts of) the major in question (Niessen et al., 2018). However, in other education systems, prospective students must decide on a major without having any study experience in that major. In these cases, they likely have misconceptions about the contents of the study major (Heublein, 2014). For example, they might expect content in the undergraduate psychology major that is not part of the curriculum. Misconstruing an event (in our example having wrong expectations regarding the content of the undergraduate psychology major) in turn can lead to biased forecasts (Wilson & Gilbert, 2003). Following this rationale, assessing prospective students’ interest-major fit forecast based on a valid theory (person-environment fit theory) and based on a valid construal of the future situation (in our example a valid construal of the undergraduate psychology major based on expert estimates of the psychology major) should improve the prediction of intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being. Thus, we propose assessing prospective students’ interest (person) in specific contents which represent a valid construal of the respective study major (environment). Important criteria for ensuring that specific contents represent a valid construal of a study major are the following (Merkle et al., 2021): The specific contents should cover all central subfields of the respective study major (exhaustiveness), should be unambiguously assignable to the corresponding subfields of the respective study major (structure) and these subfields should be evenly covered so that no subfield is over- or underrepresented (prototypicality).

Following this procedure for the construction of the assessment of interest-major fit should lead to a more objective forecast of interest-major fit which is why we refer to it as objective interest-major fit forecast. Objective interest-major fit forecast should reduce the bias in prospective students’ forecast which is due to prospective students’ misconceptions about the contents of the study major. Thus, objective interest-major fit forecast should improve the prediction of intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being.

1.5 Research question and hypotheses

Thus, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to examine factors that fulfill two necessary conditions to support students in their decision-making process for a study major: First, the factors target a specific study major and thus have the potential to predict students’ intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in a specific study major (versus targeting studying in general and predicting subjective well-being during studying independent of a specific major). Second, these factors are assessed even before students start studying. As predictors we will specifically examine prospective students’ direct forecast of their subjective well-being (well-being forecast), students’ subjective forecast of their interest-major fit (subjective interest-major fit forecast) as well as interest-major fit measured objectively with a scientifically developed and validated interest test in an online-self-assessment (objective interest-major fit forecast). The theoretical arguments presented above can be transposed into a theoretical framework (Fig. 1) that includes the following hypotheses.

Hypothesized theoretical framework for the prediction of intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being within a study major by well-being forecast, subjective interest-major fit forecast (subjective IMFF) and objective interest-major fit forecast (objective IMFF). Black lines represent hypotheses while grey lines represent controls

Prospective students already have many years of personal experience in different learning environments before entering university. Therefore, we hypothesize that a higher prospective student well-being forecast predicts higher later intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being (positive affect, negative affect, satisfaction) within their major (hypothesis 1). Directing prospective students’ forecast away from possible inaccurate theories to an empirically proven cause of later subjective well-being, such as interest-major fit, should improve this prediction of subjective well-being. Thus, we hypothesize that a higher prospective student subjective interest-major fit forecast predicts higher later intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being within their major (positive affect, negative affect, satisfaction) beyond prospective students’ well-being forecast (hypothesis 2). Additionally, assuring a valid construal of the respective major in the process of assessing interest-major fit forecasts (objective interest-major fit forecast) should reduce the bias in prospective students’ forecast which is due to prospective students’ misconceptions about the contents of the study major. Therefore, we hypothesize that a higher prospective student objective interest-major fit forecast predicts higher later intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being within their major (more positive affect, less negative affect, higher satisfaction), beyond prospective students’ well-being forecast and subjective interest-major fit forecast (hypothesis 3).

2 Method

2.1 Sample and procedure

In a first step (t1), we collected data of 4,262 prospective students who completed an online-self-assessment for psychology (OSA-Psych) prior to their enrollment in the period between February 2020 and September 2021 to self-reflect on whether psychology is the major which they want to decide on. Before they completed the online-self-assessment they agreed that their data can be used for scientific purposes and voluntarily took part in an accompanying survey. In the survey they answered questions about their demographics, their trait subjective well-being, their well-being forecast within the psychology major and their subjective interest-major fit forecast. In the online-self-assessment, prospective students’ objective interest-major fit was assessed and reported back in a feedback.

Of these 4,262 prospective students, 234 started studying psychology in the 2020 or 2021 cohort, took part in a second survey within their first two months of study at one of five surveyed universities (t2) and thus form the sample for our analyses (Mage = 20.07, SD = 2.67, range = 17–42 years, 87.2% women). In the second survey they were asked about their intrinsic motivation, satisfaction as well as positive and negative affect within their study major and received either credit points or an online-shopping voucher in exchange for their participation. All instructions and measures were provided in German.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Well-being forecast

To obtain a reliable measure and valid score of well-being forecast, we combined different approaches to measure affective forecasting. First, we used a single item which is often used in the affective forecasting literature to measure affective forecasts, asking how happy one would be in a specific situation (Gilbert et al., 1998). We adapted this item to the study context, asking “I would be happy in the undergraduate psychology major”. However, to be able to estimate the reliability and validity of this measure, we added four more items. Two items were based on the study satisfaction scale from Westermann et al. (1996) and adapted to the future tense “I would really enjoy studying in an undergraduate psychology major” and “Overall, I would be satisfied with an undergraduate psychology major”. One more item was adapted from Diener et al.’s (1985) life satisfaction scale and adapted to the future tense and the study context “In most areas, studying in an undergraduate psychology major would meet my ideal expectations” and one more item was self-constructed to reflect the affective component of subjective well-being “It would feel really good to study in an undergraduate psychology major”. Participants used a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 7 (applies completely) to indicate how they envision the future undergraduate psychology major. As the scale was self-constructed, we conducted a pretest which showed first empirical evidence for its reliability, as well as its factorial and construct validity.Footnote 1 The internal consistency in the present study was good with Cronbach’s α = .86.

2.2.2 Subjective interest-major fit forecast

We adapted three items from Etzel and Nagy’s (2016) need-supply fit in the academic context scale to measure subjective interest-major fit forecast in the academic context by replacing the word expectations with the word interests (e.g., “The offerings of the undergraduate psychology major fit my expectations of the major” was adapted to “The offerings of the undergraduate psychology major fit my interests”). Participants used a 7-point Likert scale to indicate the extent to which each statement applied to them ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (completely). The internal consistency for the scale was good, Cronbach’s α = .81.

2.2.3 Objective interest-major fit forecast

Objective interest-major fit forecast was assessed using the interest subscale of the expectation-interest test (Merkle et al., 2021) which consists of 61 items: 55 items addressing all central contents of the undergraduate psychology major (environment); six items addressing content that is often mistaken for content of the undergraduate psychology major. Prospective students (person) could rate on a 7-point Likert scale how interested they were in the specific contents (e.g., “which causes underlie mental disorders”) on a scale ranging from − 3 (not interested at all) to 3 (very much interested). The objective interest-major fit forecast (person-environment fit) was calculated by building the mean of the 55 interest items regarding central contents, the higher the value the higher the interest-major fit forecast. The internal consistency for the interest subscale was excellent, Cronbach’s α = .91.

2.2.4 Intrinsic motivation

Intrinsic study motivation was assessed using an adapted German translation (Messerer, Karst & Janke, 2023) of the interest subscale of the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (Deci & Ryan, 2013). It consisted of 6 items; sample item: “I find it exciting to study”. The scale was anchored at 1 (not true at all) and 7 (completely true). The internal consistency for this scale was excellent, Cronbach’s α = .92.

2.2.5 Subjective well-being

To measure subjective well-being within a specific major we assessed study satisfaction with a subscale of Westermann et al.’s (1996) study satisfaction scale which explicitly addresses satisfaction with the content of the studies. The subscale consists of three items (e.g., “Overall, I am satisfied with the undergraduate psychology major.”). Participants had to rate to what degree each statement applied to them on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (completely). The scale showed a good internal consistency, Cronbach’s α = .86.

Additionally, we assessed positive and negative affect with a slightly modified version of the German Version (Rahm et al., 2017) of the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE, Diener et al., 2010). Participants were instructed to indicate on six items how frequently they felt this way in the first weeks of their semester “positive”, “good”, “happy”, “pleasant”, “content” “joyful” and on six items how frequently they felt “negative”, “bad”, “sad” “unpleasant, “afraid”, “angry”). The scale was anchored at 1 (very rarely or never) and 7 (very often or always). Following Rahm et al.’s (2017) conceptualization of this measure and in congruence with confirmatory factor analyses results, positive and negative affect scores were computed separately,instead of together as a common difference score.Footnote 2 Internal consistency for the positive affect subscale was excellent, Cronbach’s αPos = .89, internal consistency for the negative affect subscale was good, αNeg = .80.

2.2.6 Control variables

To control for trait subjective well-being, we used two single items. We asked participants to report satisfaction (item taken from Beierlein et al., 2014) and happiness (item taken from Breyer & Voss, 2016) with their own life on scales from 1 to 7. Given the correlation of r = .81, we use the mean score of these two items.

2.3 Data analysis

We tested our hypotheses using hierarchical multivariate multiple regression analyses conducted in R (Version 4.1.2, R Core Team, 2021). In step one, we included trait subjective well-being as a control variable, in step two we added prospective students’ well-being forecast as a predictor, in step three prospective students’ subjective interest-major fit forecast and in step four we included objective interest-major fit forecast as a predictor. As outcomes we included intrinsic motivation, positive affect, negative affect, and satisfaction in the study major. A multivariate analysis was conducted to show for each predictor whether it uniquely and significantly contributes to explaining intrinsic motivation, positive affect, negative affect, and satisfaction in the study major (all outcomes considered together). Univariate analyses were conducted to provide more insights about each predictor’s contribution to predicting each specific outcome (all outcomes considered separately). Effect sizes were measured by Cohen’s f2. The recommended interpretation of Cohen’s f2 is 0.01 = small effect, 0.06 = medium effect, 0.14 = large effect (cf. Khalilzadeh & Tasci, 2017).

3 Results

The descriptives and zero-order correlations between all continuous variables in the following analyses are depicted in Table 1. All associations between the predictors and outcomes were significant and pointed in the expected direction.

Our goal was to predict first semester students’ intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being (positive affect, negative affect, satisfaction) in a specific major with prospective students’ well-being forecast (hypothesis 1), subjective interest-major fit forecast (hypothesis 2) and objective interest-major fit forecast (hypothesis 3).

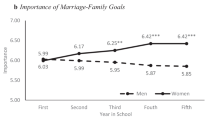

The multivariate analysis showed that trait subjective well-being (Pillai’s trace = .12, p < .001), well-being forecast (Pillai’s trace = .06, p = .003) and interest-major fit forecast (Pillai’s trace = .07, p < .001) proved to be overall significant predictors, while subjective interest-major fit forecast was not significant overall (Pillai’s trace = .03, p = .155). The results of the hierarchical univariate analyses are depicted in Fig. 2 (for further details, see Table 2). To be able to describe all results belonging to a particular hypothesis in a common section, the results of the univariate analyses (which were calculated with all predictors for each outcome separately) are summarized below across all outcomes and reported per predictor.

Results of the hierarchical univariate multiple regression analyses for the prediction of intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being within a study major by well-being forecast, subjective interest-major fit forecast (subjective IMFF) and objective interest-major fit forecast (objective IMFF). All regression coefficients are standardized (for further details, see Table 2). Black lines represent hypotheses while grey lines represent controls. Solid lines represent significant relations while dotted lines represent nonsignificant relations. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

3.1 Trait subjective well-being predicts motivation and well-being in a major

Higher trait subjective well-being was a significant predictor of higher intrinsic motivation, more positive affect, less negative affect, and higher study satisfaction. The effect sizes indicated small to medium effects (for further details, see Table 2, step 1 of each model).

3.2 Well-being forecast predicts motivation and well-being in a major

Hypothesis 1 stated that a higher prospective student well-being forecast predicts higher later intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being within their major (positive affect, negative affect, satisfaction). In line with our hypothesis, our analyses showed that a higher well-being forecast incrementally predicted higher intrinsic motivation, more positive affect, and higher satisfaction. However, unexpectedly, the relationship with negative affect was not significant but pointed in the expected direction. Thus, hypothesis 1 was partly supported. The effect sizes indicated no effect to small effects (for further details, see Table 2, step 2 of each model).

3.3 Subjective interest-major fit forecast predicts motivation and well-being in a major

Hypothesis 2 stated that a higher prospective student subjective interest-major fit forecast predicts higher later intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being within their major (positive affect, negative affect, satisfaction) beyond prospective students’ well-being forecast and trait subjective well-being. Our results partially supported this hypothesis as higher subjective interest-major fit forecast predicted more intrinsic motivation, less negative affect and higher study satisfaction beyond prospective students’ well-being forecast and trait subjective well-being. Contrary to our hypothesis, no incremental variance was explained for positive affect even though the beta pointed in the expected direction. Thus, hypothesis 2 was partially supported. The effect sizes indicated no effect to small effects (for further details, see Table 2, step 3 of each model).

3.4 Objective interest-major fit forecast predicts motivation and well-being in a major

Hypothesis 3 stated that a higher prospective student objective interest-major fit forecast predicts higher later intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being within their major (positive affect, negative affect, satisfaction), beyond prospective students’ subjective interest-major fit forecast, students’ well-being forecast and trait subjective well-being. As expected, our analyses showed that higher objective interest-major fit forecast predicted higher intrinsic motivation, more positive affect, and higher study satisfaction. However, it did not predict negative affect, but the beta pointed in the expected direction. Thus, hypothesis 3 was supported for intrinsic motivation, positive affect, and study satisfaction but not for negative affect. The effect sizes indicated no effect to medium effects (for further details, see Table 2, step 4 of each model).

4 Discussion

Predicting intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being within a specific study major before enrolling is crucial to support prospective students in their study decision process when choosing a major. There exist many studies that identified several factors assessed during studying predicting the intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being of students for studying in general (e.g., Lesener et al., 2020; Sood et al., 2012). However, there is almost no research dedicated to identifying factors measurable before enrolling to predict motivation and well-being in a specific major. Thus, combining theories about affective forecasting (e.g., Wilson & Gilbert, 2003) and person-environment fit theory (e.g., Le et al., 2014), we examined in a longitudinal field design to which extent prospective students’ well-being forecast and beyond that subjective interest-major fit forecast and objective interest-major fit forecast can predict intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in their major.

4.1 Summary of findings and theoretical implications

We showed that a higher prospective student well-being forecast predicted higher intrinsic motivation, positive affect, and satisfaction in their study major beyond prospective students’ trait subjective well-being. These results are in accordance with past findings in the affective forecasting literature indicating that people can predict their subjective well-being in specific situations to some extent (e.g., Gilbert et al., 1998; Wilson & Gilbert, 2003). We obtained these results while controlling for trait subjective well-being, suggesting that prospective students do not only project their trait average subjective well-being into the future but that they probably have some more insight about the specific future situation. However, prospective students’ well-being forecast explained no more than five percent of variance in intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in their study major. This finding is not surprising as affective forecasting theory additionally states that many biases (such as inaccurate theories or misconstrual) prevent people from making accurate predictions (for an overview, see Wilson & Gilbert, 2003). Thus, it is likely that those biases also are at work in the context of choosing a study major and might prevent prospective students from accurately forecasting their subjective well-being in a specific major.

Further evidence for this assumption provides our finding that prospective students’ subjective interest-major fit forecast improved the prediction of intrinsic motivation, negative affect, and study satisfaction by up to two percent. This finding shows that using a predictor based on an empirically proven cause of later subjective well-being (the person-environment fit in the context of choosing a study major, e.g., Cable & DeRue, 2002; Etzel & Nagy, 2016), improved the predictions of motivation and well-being. Thus, our results indicate not only that inaccurate theories are at work when prospective students decide on a study major but also show a first way of reducing this bias.

Finally, we found that objective interest-major fit could incrementally explain up to six percent of variance of intrinsic motivation, positive affect, and study satisfaction in a study major. These results demonstrate that using a predictor that reduces a potential misconstrual of the future situation (in our example a misconstrual of the undergraduate psychology major) further improves the prediction of students’ intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being. This finding is in line with past findings suggesting in different contexts that misconstrual of the future situation in question biases affective forecasts of the respective situation (Wilson & Gilbert, 2003) indicating that this is also a problem in prospective students’ process of deciding on a study major. Additionally, it explains why prospective students’ false expectations might be related to less study satisfaction (Hasenberg & Schmidt-Atzert, 2013) and adds to the existing literature a possible way to reduce such misconceptions in the study decision context to improve forecasts.

Taken together our research shows that prospective students can predict their intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in a specific major and that this prediction can further be improved by reducing affective forecasting biases. Thus, our research contributes to the affective forecasting literature by providing specific evidence for two affective forecasting biases in a new context—the context of deciding on a study major. Additionally, our research provides important theoretical implications for the process of deciding on a study major by deepening the understanding of prospective students’ underlying challenges in the decision-making process.

4.2 Unexpected findings, limitations, and future research questions

First, subjective interest-major fit was not a significant multivariate predictor and explained a relatively small amount of variance in the univariate analyses, and no variance in positive affect. A likely explanation for this finding is that the predictive power of subjective interest-major fit is not very strong, especially beyond trait subjective well-being and well-being forecast. One possible explanation for this small predictive power is that subjective interest-major fit only improves inaccurate theories. Thus, the condition for an improvement is prospective students’ use of inaccurate theories when making their well-being forecast. However, past research indicates that students already pay attention to their interest-major fit (an empirically proven cause of well-being, Etzel & Nagy, 2016) when choosing a study major (Janke et al., 2021; Watt et al., 2012) and thus it is likely that they also pay attention to this factor when making their well-being forecast. In addition, asking prospective students for their subjective interest-major fit forecast may have already acted as an intervention that led prospective students to take this factor into account when forecasting their well-being. If prospective students already accounted for their subjective interest-major fit forecast in their well-being forecast, this would explain why subjective interest-major fit forecast failed to predict intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being beyond well-being forecast (or only did so to a small extent). At the same time, it leaves open the possibility that the predictive power of subjective interest-major fit might be more robust and stronger at an even earlier stage (before attention is drawn to subjective interest-major fit). This interpretation is further supported by the fact that the zero-order correlations between subjective interest-major fit and all outcomes were significant while the hierarchical multiple regression analyses showed no or only small effects sizes for the incremental predictive value of subjective interest-major fit on the prediction of all outcomes after controlling for well-being forecast. Therefore, future studies should examine well-being forecast before attention is drawn to empirically proven causes for well-being to provide a better baseline measure of irrational theories. Moreover, in our study we focused on one single (subjective) theory in the study choice process. Future studies could examine in more depth which other factors prospective students consider important when choosing their future study major by building on existing research on different motivations for enrollment (Janke et al., 2021; Watt et al., 2012) to better understand the underlying processes of prospective students’ subjective theories in the study choice process.

Second, objective interest-major fit forecast did not significantly predict negative affect. Thus, one could conclude that objective interest-major fit forecast does not play a role in the perception of negative affect during studying. However, descriptively, the prediction pointed in the expected direction and even proved significant in the zero-order correlations. These results suggest that the predictive power of objective interest-major fit forecast for negative affect is probably not strong enough to persist beyond trait subjective well-being, well-being forecast, and subjective interest-major fit forecast. One possible reason for the small effect size is that the objective interest-major fit forecast scores of the respective samples are in a very high range (scores ranged from − 0.33 to 2.93, based on a − 3 to 3 Likert-like-scale). This is not surprising since we are dealing with a very special sample, namely those prospective students who, after using an online-self-assessment and the accompanying reflection on their interest-major fit forecast, made an informed decision to apply for a place in the respective major, received and accepted it, and finally even voluntarily participated in the survey. The resulting almost only positive level of objective interest-major fit forecast leaves enough variance to allow students with a higher positive objective interest-major fit forecast (compared to a lower positive objective interest-major fit forecast) to feel more positive emotions but leaves no room for negative emotions caused by a poor objective interest-major fit. Accordingly, this finding is aligned with the control-value theory of achievement emotions (Pekrun, 2006) stating that negative emotions only occur for negative values. This reasoning underscores the importance of the size of predictive power found for objective interest-major fit forecast, which significantly predicted intrinsic motivation, positive affect, and study satisfaction not only beyond trait subjective well-being, well-being forecast and subjective interest-major fit forecast but also despite massive restrictions in its variance.

Third, the results in the present study were obtained within the first academic year. Although motivation in the first year has been shown to predict motivation in later years (Messerer, Scherer, et al., 2023), following the argumentation of Niessen et al. (2016), data from later years are needed to gain insight into the long-term predictive power of the predictors, which may decrease with increasing time interval. Additionally, the outcomes in the present study show medium to strong correlations which raise the question of whether univariate analyses are appropriate or whether their results are partly redundant. To avoid inflated results we conducted multivariate analyses to examine our predictor effects’ controlling for the correlations between our outcomes. However, as our outcomes are not only theoretically distinguishable but also empirically distinct (as shown by the results of the confirmatory factor analysis reported in the measures section), conducting univariate analyses for each outcome gives us valuable insights in the psychological mechanisms underlying each of these variables.

Additionally for all indicators it should be considered that the present study was an ecologically valid field study, conducted in a setting with limited control of the situation (prospective students took part in the online-self-assessment as they were in their study major decision process, not in the context of taking part in a research study). Therefore, it is plausible that effect sizes do not reach the same size as in controlled experimental labor settings. Compared to the variance explained by well-established constructs such as trait subjective well-being, the reported effect sizes can even be considered comparatively good, as the well-being forecast, and the objective interest-major fit forecast can each incrementally explain (almost) as much variance in intrinsic motivation and satisfaction in the respective major as trait subjective well-being does.

Furthermore, it should be mentioned that all participants were (prospective) psychology students and consequently the interest test was specifically designed for the psychology major. Therefore, further studies should be conducted in other majors to check whether the findings can be generalized. However, as it is very hard to get a place to study psychology in Germany it is assumed that effect sizes of interest tests could be even stronger in other study majors as psychology students are probably more restricted in their variance of interest as well as intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in their major.

Finally, our results suggest that an objective interest-major fit forecast can predict intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being and therefore should be considered in study decision processes. However, we do not know yet whether prospective students automatically incorporate these scores in their decisions which is essential for the efficacy of such interest tests in the study choice decision process. Thus, future research should examine whether prospective students who receive feedback regarding their interest-major fit forecast take this score into account in their study choice process or whether more support is needed for prospective students to use such feedback in an adequate way.

4.3 Practical implications

Assuming some generalizability of the present results, important practical implications can be derived from our studies. The first implication is that to some extent prospective students should trust their “gut” feeling as it has proven to be a significant predictor that goes beyond prospective students’ potential projection based on their trait subjective well-being. However, many prospective students still feel overwhelmed with their study choice process.

To support students in this process, a wide variety of online-self-assessments has been developed over the last years which has been used by a high number of prospective students to self-reflect upon their expectations, interests, and skills (Hell, 2009). They are attractive for prospective students as they are easily accessible and free of charge and attractive for universities as they come with very low maintenance costs once they are developed, especially when weighed against the high potential costs of study dropout for both the individual as well as society due to poor study choices (Behr et al., 2020). Thus, they could have a big impact on prospective students’ study decisions which makes it even more important to find out whether online-self-assessments can be valuable guides or whether they lead prospective students astray. Our research demonstrates that an interest-major fit forecast measured objectively via an online-self assessment shows a relatively good incremental predictive validity compared with other established constructs in the field study, given the premise that it is developed using scientific methods to ensure structure, exhaustiveness and prototypicality of items regarding the study content (Merkle et al., 2021). Therefore, our results suggest that the use of online-self-assessments to assess interest-major fit should be promoted as they yield the potential to be cost-efficient tools to support prospective students in the decision-making process. The potential of using the results of online-self-assessment should be particularly high in admission procedures where there is a focus on the fit between students and the study major with an aim for high content validity. According to Niessen et al. (2016), one example for such a procedure would be the open admission program in the Netherlands where applicants take part in a mandatory matching procedure with nonbinding advice before they can self-select their study major. To better integrate online-self-assessments, we recommend as a first step, to invest time and money in a scientific development and continuous evaluation of online-self-assessments that assess interest-major fit in the study decision process. It could be argued that the development of new objective interest-major fit assessments is superfluous because the RIASEC model (Eder & Bergmann, 2015; Holland, 1959, 1997) has sometimes been used to operationalize interest-major fit (Allen & Robbins, 2010; Tracey & Robbins, 2006; Usslepp et al., 2020). However, the RIASEC operationalization of interest-major fit is based on vocational interests (Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional) whereas our operationalization is based on interests in contents of the respective study major. An operationalization of interest-major fit based on contents of the respective study major should be more accurate than an operationalization based on vocational content and showed a stronger association to study satisfaction in a recent study (Messerer, Merkle, et al., 2023). For these reasons we used an objective interest-major fit assessment based on interest in the contents of the study major in our paper and believe it makes sense to invest in the development of this type of interest-major fit assessments. Second, it seems promising to further motivate prospective students to use these tools. This could be done by restructuring the current online-self-assessment landscape in the study decision process to improve students experience by better guiding them in their study decision process. Additionally, the use of a validated online-self-assessment could be made a mandatory requirement for enrollment as it is already common practice in some universities.

4.4 Conclusion

The purpose of the current work was to examine factors that can predict students’ intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in a specific study major even before the start of studies. We found that a higher prospective student well-being forecast and beyond that a higher subjective interest-major fit forecast and a higher objective interest-major fit forecast predicted higher intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being in their study major. As one of the first studies to examine predictors of intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being prior to university enrollment in a specific major, this work underlines the importance of prospective students’ subjective forecasts in the study choice process. At the same time, it highlights the benefits of more objective predictors, such as objective interest-major fit forecast and identifies several important starting points for future interest-major fit research as well as online-self-assessment practice.

Data availability

Datasets generated and analyzed as part of the current study are not publicly available because participant consent does not allow data to be shared with researchers other than those on the project.

Notes

In the pretest the reliability of the scale was excellent (α = .92) and did not improve if any item was omitted, thus all items were kept. The fit statistics retrieved through a confirmatory factor analysis for a one-dimensional model indicated a good model fit, χ2(10) = 379.66, p < .001; CFI = .995; RMSEA = .039; SRMR = .023 (based on the guidelines by Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003). As expected, based on previous research (Wilson & Gilbert, 2003), the scale showed medium to strong correlations to current subjective well-being in their major: more positive affect (r = .70, p < .001), less negative affect (r = .57, p < .001), more study satisfaction (r = .81, p < .001). Additionally, students did forecast more subjective well-being in their major when they reported more intrinsic value (r = .75, p < .001), higher attainment value (r = .61, p < .001), higher utility value (r = .48, p < .001) and higher subjective interest-major fit (r = .65, p < .001).

Confirmatory factor analyses were computed separately for a one-factor-solution, a bi-factor-solution, and a tri-factor solution (positive vs. negative affect vs. study satisfaction) using R (Version 4.1.2; R Core Team, 2021). The models were compared regarding their information criteria (AIC, BIC), which revealed that the three-factor-solution, AIC = 24,012.74, BIC = 24,059.57 should be preferred to the two-factor-solution, AIC = 24,410.74; BIC = 24,454.73, should be preferred to the one-factor solution, AIC = 24,744.47; BIC = 24,882.30.

References

Aknin, L. B., Norton, M. I., & Dunn, E. W. (2009). From wealth to well-being? Money matters, but less than people think. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 523–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903271421

Allen, J., & Robbins, S. (2010). Effects of interest–major congruence, motivation, and academic performance on timely degree attainment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017267

Bean, J. P., & Metzner, B. S. (1985). A conceptual model of nontraditional undergraduate student attrition. Review of Educational Research, 55(4), 485–540. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430550044

Behr, A., Giese, M., Teguim Kamdjou, H. D., & Theune, K. (2020). Dropping out of university: A literature review. Review of Education, 8(2), 614–652. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3202

Beierlein, C., Kovaleva, A., László, Z., Kemper, C. J., & Rammstedt, B. (2014). Eine Single-Item-Skala zur Erfassung der Allgemeinen Lebenszufriedenheit: Die Kurzskala Lebenszufriedenheit-1 (L-1) [A single-item scale to measure general life satisfaction: the short scale Life Satisfaction-1 (L-1)]. GESIS-Working Papers, 2014/33. GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-426681.

Bretz, R. D., & Judge, T. A. (1994). Person-organization fit and the theory of work adjustment: Implications for satisfaction, tenure, and career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44(1), 32–54. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1003

Breyer, B., & Voss, C. (2016). Happiness and Satisfaction Scale (ISSP). ZIS - the Collection Items and Scales for the Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.6102/ZIS240

Cable, D. M., & DeRue, D. S. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.875

Clark, M. H., & Schroth, C. A. (2010). Examining relationships between academic motivation and personality among college students. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(1), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2009.10.002

Conner, M., McEachan, R., Taylor, N., O’Hara, J., & Lawton, R. (2015). Role of affective attitudes and anticipated affective reactions in predicting health behaviors. Health Psychology, 34(6), 642–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000143

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). Intrinsic Motivation Inventory. http://www.psych.rochester.edu/SDT/measures/intrins.html.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Eder, F., & Bergmann, C. (2015). Das Person-Umwelt-Modell von J. L. Holland: Grundlagen—Konzepte—Anwendungen [The Person-Environment-Model of J. L. Holland: Fundamentals—Concepts—Applications]. In C. Tarnai & F. G. Hartmann (Eds.), Berufliche Interessen Beiträge zur Theorie von J. L. Holland (pp. 11–30). Waxmann.

Edwards, J. R., & Shipp, A. J. (2007). The relationship between person-environment fit and outcomes: An integrative theoretical framework. In C. Ostroff & T. A. Judge (Eds.), Perspectives on organizational fit (pp. 209–258). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203810026

Etzel, J. M., & Nagy, G. (2016). Students’ perceptions of person–environment fit: Do fit perceptions predict academic success beyond personality traits? Journal of Career Assessment, 24(2), 270–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072715580325

Geiser, S., & Santelices, M. V. (2007). Validity of high-school grades in predicting student success beyond the freshman year: High-School record versus standardized tests as indicators of four-year college outcomes. Center for Studies in Higher Education, University of California.

Gilbert, D. T., Pinel, E. C., Wilson, T. D., Blumberg, S. J., & Wheatley, T. (1998). Immune neglect: A source of durability bias in affective forecasting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 617–638. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.617

Hasenberg, S., & Schmidt-Atzert, L. (2013). Die Rolle von Erwartungen zu Studienbeginn: Wie bedeutsam sind realistische Erwartungen über Studieninhalte und Studienaufbau für die Studienzufriedenheit [The role of expectations at the beginning of Academic studies: How important are realistic expectations for students’ satisfaction?]? Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 27(1–2), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652/a000091

Heinze, D. (2018). Die Bedeutung der Volition für den Studienerfolg [The importance of volition for study success]. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-19403-1

Hell, B. (2009). Selbsttests zur Studienorientierung: Nützliche Vielfalt oder unnützer Wildwuchs [Self-assessments for study orientation: Useful variety or useless proliferation?]? In G. Rudinger (Ed.), Self-Assessment an Hochschulen: Von der Studienfachwahl zur Profilbildung [Self-assessment at universities: From selecting a major to profile formation] (pp. 9–19). V&R Unipress.

Heublein, U. (2014). Student drop-out from german higher education institutions. European Journal of Education, 49(4), 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12097

Holland, J. L. (1959). A theory of vocational choice. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 6(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040767

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (3rd ed.). Psychological Assessment Resources.

Janke, S., Messerer, L. A. S., Merkle, B., & Krille, C. (2021). STUWA: Ein multifaktorielles Inventar zur Erfassung von Studienwahlmotivation [STUWA: A multifactorial inventory for the assessment motivation for enrollment]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 37(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652/a000298

Khalilzadeh, J., & Tasci, A. D. A. (2017). Large sample size, significance level, and the effect size: Solutions to perils of using big data for academic research. Tourism Management, 62, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.03.026

Le, H., Robbins, S. B., & Westrick, P. (2014). Predicting student enrollment and persistence in college STEM fields using an expanded P-E fit framework: A large-scale multilevel study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(5), 915–947. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035998

Lesener, T., Pleiss, L. S., Gusy, B., & Wolter, C. (2020). The study demands-resources framework: An empirical introduction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145183

Merkle, B., Schiltenwolf, M., Kiesel, A., & Dickhäuser, O. (2021). Entwicklung und Validierung eines Erwartungs- und Interessenstests (E × I - Test) zur Erkundung studienfachspezifischer Passung in einem Online-Self-Assessment [Development and validation of an Expectation-Interest Test (E × I - Test) to explore fit for a specific major in an online self-assessment]. ZeHf - Zeitschrift Für Empirische Hochschulforschung, 5(2), 162–183. https://doi.org/10.3224/zehf.5i2.05

Messerer, L. A. S., Karst, K., & Janke, S. (2023): Choose wisely: intrinsic motivation for enrollment is associated with ongoing intrinsic learning motivation, study success and dropout Studies in Higher Education, 48(1), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2121814

Messerer, L. A. S., Merkle, B., Karst, K., & Janke, S. (2023). Interest-Major Fit Predicts Study Success? Comparing Different Ways of Assessment. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Messerer, L. A. S., Scherer, R., Karst, K., & Janke, S. (2023). Is Every Semester the Same? The Interplay Between Intrinsic Motivation and Grades and How They Relate to Dropout Over the Course of University Studies. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Mokgele, K. R., & Rothmann, S. (2014). A structural model of student well-being. South African Journal of Psychology, 44(4), 514–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246314541589

National Center for Education Statistics. (2018). Beginning college students who change their majors within 3 years of enrollment (NCES 2018-434). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED578434.pdf.

Niessen, A. S. M., Meijer, R. R., & Tendeiro, J. N. (2016). Predicting performance in higher education using proximal predictors. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0153663. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153663

Niessen, A. S. M., Meijer, R. R., & Tendeiro, J. N. (2018). Admission testing for higher education: A multi-cohort study on the validity of high-fidelity curriculum-sampling tests. PLoS ONE, 13(6), e0198746. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198746

Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

Rahm, T., Heise, E., & Schuldt, M. (2017). Measuring the frequency of emotions—Validation of the scale of positive and negative experience (SPANE) in germany. PLoS ONE, 12(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171288

Respondek, L., Seufert, T., Stupnisky, R., & Nett, U. E. (2017). Perceived academic control and academic emotions predict undergraduate university student success: Examining effects on dropout intention and achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00243

R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 4.1.2) [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23–74.

Schindler, I., & Tomasik, M. J. (2010). Life choices well made: How selective control strategies relate to career and partner decision processes. Motivation and Emotion, 34(2), 168–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-010-9157-x

Sood, S., Bakhshi, A., & Gupta, R. (2012). Relationship between personality traits, spiritual intelligence and well-being in university students. Journal of Education and Practice, 3(10), 55–60.

Soppe, K. F. B., Wubbels, T., Leplaa, H. J., Klugkist, I., & Wijngaards-de Meij, L. D. N. V. (2019). Do they match? Prospective students’ experiences with choosing university programmes. European Journal of Higher Education, 9(4), 359–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2019.1650088

Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134(1), 138–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.138

Tracey, T. J., & Robbins, S. B. (2006). The interest–major congruence and college success relation: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(1), 64–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.11.003

Usslepp, N., Hübner, N., Stoll, G., Spengler, M., Trautwein, U., & Nagengast, B. (2020). RIASEC interests and the Big Five personality traits matter for life success—But do they already matter for educational track choices? Journal of Personality, 88(5), 1007–1024. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOPY.12547

Watt, H. M., Richardson, P. W., Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Beyer, B., Trautwein, U., & Baumert, J. (2012). Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: An international comparison using the FIT-Choice scale. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(6), 791–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.03.003

Westermann, R., Elke, H., Spies, K., & Trautwein, U. (1996). Identifikation und Erfassung von Komponenten der Studienzufriedenheit [Identification and recording of components of student satisfaction]. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 43(1), 1–22.

Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. T. (2003). Affective forecasting. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 35, pp. 345–411). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(03)01006-2

Wong, W. H., & Chapman, E. (2022). Student satisfaction and interaction in higher education. Higher Education. Advance online publication. 85(5), 957–978 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00874-0

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The presented research was funded by the Ministry of Science, Research, and the Arts of the State of Baden-Württemberg to Oliver Dickhäuser.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by BM. The first draft of the manuscript was written by BM and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval and consent

Informed consent was obtained for all participants. The Ethics Review Panel of the Faculty of Behavioural and Cultural Studies of the University of Heidelberg approved the study on 20th of July, 2019.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Merkle, B., Messerer, L.A.S. & Dickhäuser, O. Will I be happy in this major? Predicting intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being with prospective students’ well-being forecast and interest-major fit forecast. Soc Psychol Educ 27, 237–259 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09835-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09835-6