Abstract

Teachers have a major impact on students’ social cognition and behaviors, and previous research has found that students who have positive relationships with their teachers tend to be less bullied by their peers. However, this line of research is limited in that it has been (a) Dominated by cross-sectional studies and (b) Treated bullying victimization as a global construct without differentiating among its different forms (i.e., verbal, physical, and relational). The links might be reciprocal but further studies are needed to investigate the directionality. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the longitudinal associations between student–teacher relationship quality and two forms of bullying victimization, namely verbal and relational victimization. Three waves of data from 1885 Swedish fourth- through sixth-grade students were analyzed with cross-lagged panel models. The findings showed that the student–teacher relationship quality predicted and was predicted by verbal and relational victimization. Our findings thus underscore the importance of striving for caring, warm, supportive, and respectful student–teacher relationships as a component of schools’ prevention efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Bullying can be defined as repeated aggression or inhumane behaviors toward individuals who are less powerful in relation to the perpetrator(s) (Hellström et al., 2021) and occurs in different forms including physical, verbal, and relational bullying (Borntrager et al., 2009). Bullying victimization is associated with various negative health outcomes such as mental health problems (Chouhy et al., 2017; Schoeler et al., 2018) and physical health problems (Deryol & Wilcox, 2020). Researchers also show how bullying victimization is associated with poor academic performance (Fry et al., 2018) and low school liking (Bardach et al., 2022).

Bullying is a social phenomenon dependent on the social context of the school (Cui & To, 2021; Espelage et al., 2015; Saarento et al., 2015; Sjögren et al., 2021; Thornberg et al., 2019; Waasdorp et al., 2022). This includes the quality of the classroom climate and interpersonal relationships (Behrhost et al., 2020; Marengo et al., 2021; Rambaran et al., 2020; Sijtsema et al., 2014; Thornberg et al., 2018, 2022), where especially the quality of the student–teacher relationship quality has been found to be associated with levels of school bullying and victimization (Espelage et al., 2015; Longobardi et al., 2022; Thornberg et al., 2022). For example, a Swedish study found that peer victimization was less likely to occur in school classes characterized by lower moral engagement and warmer, fairer, and more supportive patterns of relationship among students and between teachers and students (Thornberg et al., 2017). In contrast, a Canadian study found that early adolescent students who reported longer duration and greater frequency of peer victimization were also more likely to report greater difficulties in their relationships with adults in school and community (Hong et al., 2020).

Since the direction of the links between student–teacher relationship quality and bullying victimization does not seem to be clear in the literature, we conducted this study to investigate the bidirectional nature of the relationship between student–teacher relationship quality and bullying victimization within a social-ecological perspective of bullying. Thus, the aim of our study was to examine the longitudinal associations between student–teacher relationship quality and two forms of bullying victimization, namely verbal and relational victimization. More specifically, we examined whether student–teacher relationship quality predicted verbal and relational victimization, whether verbal and relational victimization predicted student–teacher relationship quality, or whether there were reciprocal relationships.

1.1 A social-ecological perspective on bullying

According to the social-ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), bullying perpetration and victimization emerge, persist, and change as a result of an ongoing, reciprocal and complex interplay between individual and contextual factors (Hong & Espelage, 2012; Swearer & Hymel, 2015). A social-ecological perspective on bullying highlights how bullying is nested within four interconnected systems referred to as the micro, meso, exo- and macrosystems (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). In this study, we focus on the micro and mesosystem while also acknowledging how the exosystem (e.g., organizational level, action plans) and macrosystem level (e.g., societal norms) has an impact on bullying victimization.

The microsystem refers to those relationships and contexts, in which the individual has direct contact with as peers, parents, teachers and the immediate physical environment and its characteristics (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). A critical level of analysis in our study is the microsystem, as it involves proximal processes that play a significant role in students’ development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). In the school context, the microsystem might refer to the peer–peer relationships, the student–teacher relationships, the relationship between school principals and students, or the relationship between students and their physical school environments. One of the most important microsystems for students in school is their relationship with their teachers (Bouchard & Smith, 2017; Farmer et al., 2011). In terms of the social-ecological perspective, Bouchard and Smith (2017) argue that “the moment-by-moment teacher-student interactions can profoundly affect children’s relationships with peers, and more specifically, children’s bullying experiences” (p. 115).

Furthermore, students’ bullying experiences in the peer group may, in turn, influence their interactions and relationships with their teachers. This is highlighted in terms of the mesosystem. Mesosystem refers to the interactions of two or more microsystems that influence children’s development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Applied to the school context and with a focus on two in-school microsystems, namely the student–teacher relationship and the peer group, the interaction between these two systems can affect bullying experiences (Thornberg et al., 2018). As argued by Bouchard and Smith (2017), “the mesosystem provides perspective on the interconnected role of teachers and peers in complex social processes such as children’s bullying experiences” (Bouchard & Smith, 2017, p. 120).

Several studies have found that positive student–teacher relationships are associated with less bullying victimization, while negative student–teacher relationships are linked with greater bullying victimization (for meta-analyses, see Krause & Smith, 2022; ten Bokkel et al., 2023). In this study we chose to focus on verbal and relational bullying victimization. By also focusing on the microsystem of the student–teacher relationships we can improve our understanding of how verbal and relational victimization are associated with student–teacher relationships (Hong & Espelage, 2012).

1.2 Student–teacher relationship quality and its consequences for students

According to the social-ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), teachers play an important role in how students interact with each other in school because of their unique and salient position as classroom leaders, significant adults, and socialization agents in the school context (Bouchard & Smith, 2017; Farmer et al., 2011). Teachers interact with their students, on a daily basis especially with elementary school students who have the same teachers in most subjects and remain in the same classroom throughout their school days. How students perceive their relationships with their teachers in terms of how they interact with and treat students is thus important and when it comes to bullying prevention, specifically, teachers have been found to play a crucial role (Yoon et al., 2020).

In the present study, student–teacher relationship quality refers to the extent of caring, warm, supportive, and respectful student–teacher relationships and interaction patterns. According to this study, positive student–teacher relationships include high levels of warmth, open communication, and support provided by teachers to students, and are therefore caring, emotionally supportive, and trust-building (Sulkowski & Simmons, 2018). Negative student–teacher relationships include lack of closeness and support, anger, mutual dislike, and a lot of conflicts (Krause & Smith, 2022). Higher quality student–teacher relationships have been found to be associated with students with greater psychological well-being (Lin et al., 2022), school liking (Hallinan, 2008; Thornberg et al., 2023), academic engagement and achievement (for meta-analyses, see Roorda et al., 2017; Quin, 2017), peer relationships (for a meta-analysis, see Endedijk et al., 2022), prosocial behavior (Longobardi et al., 2021; for a meta-analysis, see Endedijk et al., 2022), motivation to defend bullying victims (Iotti et al., 2020; Jungert et al., 2016), defending victims when they witness bullying (Jungert et al., 2016; Sjögren et al., 2021), and sense of school belonging (for a meta-analysis, see Allen et al., 2018). It has also been associated with less disruptive behavior (for a meta-analysis, see Quin, 2017), externalizing behavior (for a meta-analysis, see Endedijk et al., 2022), and bullying perpetration and victimization (for meta-analyses, see Krause & Smith, 2022; ten Bokkel et al., 2023). However, two elements currently limit the findings and scope of the results regarding the links between student–teacher relationship and bullying victimization. Firstly, (a) It is dominated by cross-sectional studies and (b) Treats bullying victimization as a global construct without differentiating between its different forms.

1.3 Reciprocal negative influence between student–teacher relationship quality and bullying victimization

Although previous research has found a solid relationship between bullying victimization and student–teacher relationship quality, most studies rely on cross-sectional data, so the direction of the effect cannot be determined. However, in a recent meta-analysis of ten longitudinal studies available (ten Bokkel et al., 2023), on average, a small but significant negative association between bullying victimization and student–teacher relationship quality are found. Importantly, the studies were conducted in different countries, targeted different age groups, and used different research methods. Not surprisingly, then, results varied across the ten studies, from a non-significant effect to a small effect size, with regression coefficients ranging from -0.22 to 0.06. Among longitudinal studies that focused on elementary school children, some found support for negative longitudinal associations between positive student–teacher relationships and bullying victimization (Demol et al., 2020; Leadbeater et al., 2015; Serdiouk et al., 2016). Other studies found no significant relationship in their final models (Demol et al., 2022; Elledge et al., 2016; ten Bokkel et al., 2021). These partly inconsistent findings might be explained by methodological differences across studies such as using peer nominations to measure the quality of the student–teacher relationship (Demol et al., 2022; Elledge, 2016) or having a relatively short period of time (ten weeks) between measurements with little room to detect changes in student–teacher relationship quality and bullying victimization (Demol et al., 2022; ten Bokkel et al., 2021). Regarding the directionality of significant longitudinal effects reciprocal negative relationship between student–teacher relationship quality and bullying victimization found support in two studies (Demol et al., 2020; Leadbeater et al., 2015). These studies suggest that positive student–teacher relationships may predict higher levels of victimization and that higher levels of victimization may predict negative student–teacher relationships.

Besides the dominance of cross-sectional studies, another common feature of previous research is that bullying victimization has been treated as a global construct rather than focusing on its different forms (i.e., verbal, physical, and relational), which prevents a more fine-grained understanding of the relationship between student–teacher relationship quality and different forms of bullying victimization. Demol et al.’s (2020) study is a rare exception in this regard. Its findings suggest that the student–teacher relationship quality both predicts and is predicted by physical and relational victimization. However, a single study is not conclusive, and it should also be noted that in Demol et al.’s (2020) study, a bidirectional association was supported only from the first to the second wave, whereas there were only unidirectional effects from relationship quality to physical and relational victimization from the second to the third wave. These findings need to be replicated and extended to include also verbal bullying. In this study we extend previous research by including verbal victimization and focus on verbal and relational bullying victimization. Verbal bullying refers to an overt and direct bullying using verbal aggression such as teasing and name-calling. In contrast, relational bullying is a more covert and subtle form of bullying that includes rumor-spreading, social rejection, and social exclusion (Kennedy, 2021; Woods & Wolke, 2003).

We focus on verbal and relational victimization because previous studies suggest that these two types of bullying are most prevalent (e.g., Kennedy, 2021; Waasdorp & Bradshaw, 2015). It is also motivated to examine the unique contextual links between student–teacher relational quality and verbal and relational victimization (Casper & Card, 2017) as bullying prevention programs are found effective at reducing only relational bullying (Kennedy, 2021).

This study aimed to examine the longitudinal associations between student–teacher relationship quality and two forms of bullying victimization, namely verbal and relational victimization. More specifically, we examined whether student–teacher relationship quality predicted verbal and relational victimization, whether verbal and relational victimization predicted student–teacher relationship quality, or whether there were reciprocal relationships.

In light of the social-ecological perspective, we hypothesized to find reciprocal negative associations, that is better student–teacher relationships would predict less verbal and relational victimization, and less verbal and relational victimization would predict better student–teacher relationships. Considering that the two forms of victimization are different constructs (Casper & Card, 2017; Kennedy, 2021), and in line with the social-ecological framework (cf., Hong & Espelage, 2012), we also wanted to unpack whether there were any contextual differences between student–teacher relationships and verbal and relational victimization. We therefore distinguish between these forms of bullying to explore the interrelation between bullying forms and the micro- and mesosystem. Due to the novelty of this inquiry, we did not develop a priori hypotheses but examined possible differences in an exploratory manner. Finally, based on previous studies (Choi & Park, 2021; Chu et al., 2018; Demol et al., 2020; Hajovsky et al., 2021; Harvey et al., 2022; Pouwels et al., 2016; Zych et al., 2020), we expected significant autoregressive effects of the student–teacher relationship quality and victimization variables, indicating their relative stability over time.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

This study was part of a larger longitudinal project designed to examine social and moral correlates of peer victimization and bullying among Swedish fourth- through eighth-grade students. The original sample included 2,408 fourth-grade students from 74 schools. Out of these, 599 students did not get parental consent and 183 students were absent on the day of data collection or chose not to participate. In addition, 81 participants did not fill out the scales of student–teacher relationship quality, verbal victimization, and relational victimization. Thus, from the first wave, we analyzed data from 1,545 students (Mage = 10.54, SD = 0.35, girls = 52%). In each of the following data collection waves, some students chose to withdraw from the study, were absent on the day of data collection, or had transferred to schools that are not involved in the project, whereas some students joined in. From fourth to fifth grade, 182 students dropped out whereas 288 joined in, resulting in a fifth-grade sample of 1,651 students (Mage = 11.55, SD = 0.33, girls = 53%). From fifth to sixth grade, 256 students dropped out whereas 87 joined in, resulting in a sixth-grade sample of 1,482 students (Mage = 12.58, SD = 0.35, girls = 53%). In total, 1,885 students participated at least on one occasion. A final sample reduction was due to 91 students who transferred to other classes or schools during the study period. These students were excluded to minimize potential confounding effects that may arise from changes in teachers and classroom environments on the studied variables. Thus, the final sample consisted of 1794 students.

In Sweden, elementary school students have one classroom (homeroom) in which most of their classes take place, and they have one class teacher and only a few other teachers. Therefore, the measurement of teacher-student relationships (TSR) was not targeted to a single teacher. However, when the students responded to the scale in the present study, they only had a few close teachers, including their most significant teacher (i.e., their class teacher), to consider. Furthermore, it is common for the same teachers to stay with students from fourth to sixth grade. As a result, almost all participants in our study had the same teachers during the three measurement occasions.

Attrition between waves was analyzed by comparing the mean scores of student–teacher relationship qualities and bullying victimization among those who continued participation from the first to the second and from the second to the third waves with those who dropped out after the first and second waves, respectively. A total of eight separate t-tests were conducted, with six revealing significant differences (for a detailed overview, see Appendix A in the Online Supplementary Material). In terms of student-relationship quality, students who dropped out after the first wave reported more negative relationships during the first wave compared to those who continued to participate in the second wave. Similarly, students who dropped out after the second wave reported less positive relationship quality in the second wave compared to those who continued to participate in the third wave. Regarding verbal and relational victimization, it was found that students who dropped out after the first and second waves were victimized to a greater extent, both verbally and relationally, in the first and second waves, respectively, compared to those who continued their participation. However, the group differences can be considered small as Cohen’s d ranged from 0.18 to 0.24 (Cohen, 1988).

Participating schools were strategically selected to provide a heterogeneous sample. The sample included students from a variety of sociogeographic regions (from rural areas to medium sized and large cities) and from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds (from lower to upper-middle socioeconomic status). Across the waves, 18–19% of the students, compared to the national average of 23–25% during the school years of data collection (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2022), had an immigrant background defined as not being born in Sweden or having two foreign-born parents.), had an immigrant background defined as not being born in Sweden or having two foreign-born parents.

2.2 Procedure

Prior to conducting the study ethical approval was obtained from our Regional Ethical review board. When introducing the study, both principals and teachers were informed about the study and allowed researchers access to classrooms. Both written informed parental consent and student assent were obtained from all participants prior to conducting the data. Participating students responded to a web-based questionnaire on tablets three times at one-year intervals, within three to five months from the start of each school year. The average completion time of the questionnaire was about 30 min. In the vast majority of cases, a member of the research team led the data collection sessions, explaining the study procedure and providing assistance to participants (e.g., explaining words or phrases on the questionnaire). In a few cases, teachers administered the questionnaire. These sessions started with a short video tutorial recorded by the research team addressed to the participating students about filling out the questionnaire. Additionally, the teachers were shown a video tutorial outlining their role during the sessions prior to the data collection occasions (e.g., that they were to be passive but available to give reading assistance upon request from participants).

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Verbal and relational bullying victimization

To measure bullying victimization, we used an 11-item self-report scale that did not mention the word bullying to reduce the risk of underreporting (Kert et al., 2010) and misunderstanding about what bullying is (Frisén et al., 2008). The scale had previously displayed adequate psychometric properties when used among Swedish school children (Thornberg et al., 2018). The scale asked, “Think of the past three months in school: How often have one or more students who are stronger, more popular, or more in charge in comparison to you done the following things to you?” The question was followed by 11 behavioral items, three depicting verbal (e.g., “Teased and called me mean names”), three depicting relational (e.g., “Spread mean rumors or lies about me”), and five depicting physical (e.g., “Hit or kicked me to hurt me”) bullying victimization. For each item, the students responded on a five-point response scale ranging from 1 = has not happened to me to 5 = several times a week. In the present study, we focused on verbal and relational bullying victimization. The mean scores of the three verbal and relational items at each data collection wave were computed as index variables for verbal and relational bullying victimization, respectively. Cronbach’s α across the three waves was 0.79 to 0.87 for verbal bullying victimization and 0.77 to 0.81 for relational bullying victimization. We examined the two-dimensionality of the scale across the waves by using confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) that accounted for the hierarchical structure of the data (i.e. students nested within classrooms) and obtained reasonable fit indices: χ2(8) = 45, p < .001, CFI = 0.978, RMSEA = 0.054, SRMR = 0.03 for wave 1; χ2(8) = 84, p < .001, CFI = 0.967, RMSEA = 0.076, SRMR = 0.039 for wave 2; and χ2(8) = 91, p < .001, CFI = 0.964, RMSEA = 0.083, SRMR = 0.044 for wave 3.

Student–teacher relationship quality. To measure students’ perceived quality of their relationships with their teachers, we developed and used a 13-item self-report scale which constitutes an expansion of a 9-item scale that previously had been used among Swedish school children with adequate psychometric properties (Sjögren et al., 2021). The scale included seven items that tapped positive student–teacher relationship qualities (e.g., “My teachers really care about me”) and six items that tapped negative student–teacher relationship qualities (e.g., “My teachers don’t like me”). For each item, the students responded on a seven-point response scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. The mean score of the seven positive and six negative items at each data collection wave was computed as index variables of positive and negative student–teacher relationship quality, respectively. Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.91 to 0.94 across the three waves. We examined the two-dimensionality of the scale across the waves by using confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) that accounted for the hierarchical structure of the data and obtained reasonable fit indices: χ2(64) = 323, p < .001, CFI = 0.944, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.05 for wave 1; χ2(64) = 479, p < .001, CFI = 0.953, RMSEA = 0.062, SRMR = 0.048 for wave 2; and χ2(64) = 539, p < .001, CFI = 0.932, RMSEA = 0.071, SRMR = 0.061 for wave 3.

2.4 Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed in R Studio 1.3.1073. The lavaan package, version 0.6–9 (Rosseel, 2012), were used to estimate cross-lagged panel models (CLPM) in order to examine longitudinal associations between bullying victimization and student–teacher relationship quality. CLPM estimates the effect of a predictor variable (A) measured at time point 1 on an outcome variable (B) measured at time point 2 (i.e., the cross-lagged effect), while controlling for the rank-order stability of (A) from time point 1 to 2 (i.e., the autoregressive effect) (see Selig & Little, 2012). For instance, a significant negative cross-lagged effect of positive student–teacher relationship quality on verbal victimization between time point 1 and 2 would indicate that students with better relationships with their teachers in fourth grade are less exposed to verbal bullying in fifth grade. To estimate reciprocal longitudinal associations, one simultaneously tests whether (A) at time point 1 predicts (B) at time point 2 and whether (B) at time point 1 predicts (A) at time point 2, while controlling for their autoregressive effects.

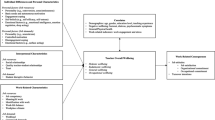

We estimated two reciprocal models, one including positive and one including negative student–teacher relationship quality (henceforth referred to as the positive and negative model, respectively) along with verbal and relational victimization. In both models, we examined the autoregressive (see paths a-f in Fig. 1) and cross-lagged effects (see paths g-n in Fig. 1) between adjacent time points. At time point 1, verbal victimization, relational victimization, and student–teacher relationship quality were allowed to covary, and at time points 2 and 3, their residuals were allowed to covary. The residual variances of the corresponding indicators were allowed to covary over time. Because χ2 is sensitive to sample size, the model was evaluated using the following fit indices: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). A CFI > 0.95, an RMSEA < 0.06, and an SRMR < 0.08 indicate adequate fit of the model (Hu & Bentler, 1999). To test for multivariate normality in the data, we conducted Mardia’s test using the mardia() function in psych package version 2.2.3. The results of the test indicated that the data deviated significantly from multivariate normality. Therefore, we used the robust MLR (Robust Maximum Likelihood) estimator to estimate the parameters of our CLPMs as the MLR estimator is known to be more robust to deviations from normality and heteroscedasticity compared to the standard ML estimator. We also used FIML (Full Information Maximum Likelihood) estimation to handle the missing data, as it is a powerful method that utilizes all available information from the observed data to estimate the model parameters. Furthermore, since the students were nested within classrooms, we accounted for this in our analyses by applying the cluster argument in the sem() function when running the cross-lagged panel models. This ensures that the estimated standard errors and confidence intervals for the parameters in the model are accurate given the hierarchical structure of the data. Additionally, we calculated the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) to measure the levels of dependency in the data regarding the nesting of students in classes. These values ranged, across the waves, from 0.13 to 0.15 for positive relationships; from 0.04 to 0.13 for negative relationships; from 0.06 to 0.13 for verbal victimization; and from 0.05 to 0.08 for relational victimization. This indicates that a portion of the variance in all variables can be attributed to the class level, which justifies the choice of using the cluster argument. In longitudinal studies, using the same scale does not guarantee that the same construct is being measured over time (Little, 2013). For example, interpretations of scale items may change as participants age or as the nature of the assessment changes from time to time. Therefore, measurement invariance was examined over time to ensure that potential associations between constructs could be reliably interpreted. To test for measurement invariance, two sets of CFA models were tested, one including positive and one including negative student–teacher relationship quality along with verbal and relational victimization. First, a CFA with unconstrained factor loadings and intercept across the three waves was conducted. Second, the unconstrained CFA was compared with a CFA in which the factor loadings were constrained to be equal over time. Weak/metric invariance was considered acceptable if the CFI did not decrease and the RMSEA did not increase by more than 0.010 and 0.015, respectively (Chen, 2007; Cheung & Renswold, 2002). In the third and final step, the CFA with constrained factor loadings was compared with a CFA in which both factor loadings and item intercepts had to be the same over time. Strong/scalar invariance was considered acceptable if CFI did not decrease and the RMSEA did not increase by more than 0.010 and 0.015, respectively, between the second and third steps (Chen, 2007; Cheung & Renswold, 2002).

The autoregressive and cross-lagged effects of the cross-lagged panel models Note. VER VIC = verbal bullying victimization, STUTEA = student-teacher relationship quality, REL VIC = relational bullying victimization. Paths a–f denote the six autoregressive effects, and paths g–n denote the eight cross-lagged effects. Note that two different models were examined, one for positive and one for negative student-teacher relationship quality.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for verbal victimization, relational victimization, and positive and negative student–teacher relationship quality in grades four through six. Mean scores for verbal and relational victimization remained stable over time, while positive and negative student–teacher relationship quality decreased and increased slightly in each grade, respectively. Table 2 shows the pairwise correlations within and between grade levels. All correlations were significant at the 0.01 level. The strongest within-grade correlations were between positive and negative student–teacher relationship quality, ranging from -0.61 to -0.72, while the within-grade correlations between student–teacher relationship qualities and bullying victimization ranged from -0.22 to -0.30. As with the correlations between-grade levels, associations between adjacent time points (i.e., from 4 to 5th grade and from 5 to 6th grade) were generally stronger compared to more distant time points (i.e., from 4 to 6th grade). Overall, the scales showed moderate stability over time, with correlations of 0.40 to 0.60 for positive student–teacher relationship quality, .39 to -.57 for negative student–teacher relationship quality, .27 to .44 for verbal victimization, and .37 to -.49 for relational victimization.

3.2 Longitudinal associations

Before estimating the model, we tested for measurement invariance and found support for strong invariance for both the positive and the negative model (see Appendix B). Consequently, we ran the hypothesized reciprocal models and found that they fit the data reasonably well, χ2(683) = 1539, p < .001, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.026; 90% CI [0.025, 0.028], SRMR = 0.040 for the positive model and χ2(574) = 1653, p < .001, CFI = 0.938, RMSEA = 0.032; 90% CI [0.031, 0.034], SRMR = 0.050 for the negative model. In the positive model, the proportion of variance explained for the endogenous variables was as follows: 0.27 (grade 5) and 0.41 (grade 6) for student–teacher relationship quality, 0.27 (grade 5) and 0.26 (grade 6) for verbal victimization, and 0.29 (grade 5) and 0.31 (grade 6) for relational victimization. In the negative model, the proportion of variance explained for the endogenous variables was as follows: 0.31 (grade 5) and 0.39 (grade 6) for student–teacher relationship quality, 0.29 (grade 5) and 0.26 (grade 6) for verbal victimization, and 0.31 (grade 5) and 0.32 (grade 6) for relational victimization.

Next, we went on to examine the autoregressive and cross-lagged effects of the models (for an overview of the standardized coefficients, see Figs. 2 and 3). All autoregressive effects were significant and quite strong (βs ranging from 0.46 to 0.61). This implies that the qualities of the students’ relationships with their teachers, as well as their exposure to bullying, were moderately to strongly stable over time or, more specifically, that the relative ordering of students on each of these constructs to a rather high degree was maintained from fourth to sixth grade.

Standardized Coefficients of the Cross-Lagged Panel Model for Positive Student–Teacher Relationship Quality, Verbal Victimization, and Relational Victimization Note. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. VER VIC = verbal bullying victimization, POS STUTEA = positive student-teacher relationship quality, REL VIC = relational bullying victimization. w1 = grade 4, w2 = grade 5, w3 = grade 6. Non-significant paths are indicated by dashed arrows. Within-time coefficients in grade 4 refer to correlations between verbal victimization, positive student-teacher relationship quality, and relational victimization, whereas within-time coefficients in grades 5 and 6 refers to their residual correlations.

Standardized Coefficients of the Cross-Lagged Panel Model for Negative Student–Teacher Relationship Quality, Verbal Victimization, and Relational Victimization Note. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. VER VIC = verbal bullying victimization, NEG STUTEA = negative student–teacher relationship quality, REL VIC = relational bullying victimization. w1 = grade 4, w2 = grade 5, w3 = grade 6. Non-significant paths are indicated by dashed arrows. Within-time coefficients in grade 4 refer to correlations between verbal victimization, negative student–teacher relationship quality, and relational victimization, whereas within-time coefficients in grades 5 and 6 refers to their residual correlations

When examining the cross-lagged paths from positive student–teacher relationship quality to bullying victimization, three out of four paths were significant. More specifically, the cross-lagged paths from positive student–teacher relationship quality to verbal victimization were negative and significant, for both T1 to T2 (β = –0.09, SE = 0.03, p = 0.019) and T2 to T3 (β = –0.07, SE = 0.02, p = 0.035), while the cross-lagged paths from student–teacher relationship quality to relational victimization were significant from T2 to T3 (β = –0.09, SE = 0.03, p = 0.043) but not from T1 to T2 (β = –0.02, SE = 0.02, p = 0.591). Thus, the results showed a significant effect of positive student–teacher relationship quality on later levels of bullying victimization, but only from grade 5 to grade 6 for relational victimization. In other words, changes in student–teacher relationship over time predicted changes in bullying victimization, where increases in positive relationship quality was associated with decreases in bullying victimization, but only from T2 to T3 for relational victimization. As for the cross-lagged paths from bullying victimization to positive student–teacher relationship quality, one out of four effects were significant. More specifically, we found a significant cross-lagged effect from relational victimization to student–teacher relationship quality from T1 to T2 (β = –0.17, SE = 0.11, p = 0.002). The other cross-lagged effects were non-significant: β = –0.02, SE = 0.22, p = 0.825 from T2 relational victimization to T3 positive student–teacher relationship quality in T3; β = –0.03, SE = 0.09, p = 0.565 from T1 verbal victimization to T2 positive student–teacher relationship quality; and β = –0.08, SE = 0.09, p = 0.206 from T2 verbal victimization to T3 positive student–teacher relationship quality.

As for the negative model, three out of four paths from relationship quality to bullying victimization were significant. Just as in the positive model, both paths to verbal victimization were significant: β = 0.16, SE = 0.04, p < .001 from T1 to T2 and β = 0.08, SE = 0.03, p = .031 from T2 to T3, while one path, from T1 to T2, was significant (β = 0.11, SE = 0.04, p = .009) and the other, from T2 to T3, was non-significant (β = 0.09, SE = 0.03, p = .063) regarding relational victimization. In other words, changes in negative student–teacher relationship, too, over time predicted changes in bullying victimization, where increases in negative relationship quality was associated with increases in bullying victimization, but only from T1 to T2 for relational victimization. In the opposite direction, from bullying victimization to negative student–teacher relationship quality, one out of four cross-lagged paths was significant, from T2 verbal victimization to T3 student–teacher relationship quality (β = 0.12, SE = 0.07, p = .036). The other cross-lagged effects were non-significant: β = 0.03, SE = 0.10, p = .664 from T1 relational victimization to T2 student–teacher relationship quality; β = -0.06, SE = 0.08, p = .337 from T2 relational victimization to T3 student–teacher relationship quality; and β = -0.01, SE = 0.08, p = 0.976 from T1 verbal victimization to T2 student–teacher relationship quality. Overall, our findings displayed the same pattern in both the positive and negative models; that the longitudinal associations between student–teacher relationship quality and verbal and relational bullying victimization can be reciprocal but that relationship quality to a greater extent predicts bullying victimization than bullying victimization predicts relationship quality.

4 Discussion

The study aimed to investigate longitudinal associations between student–teacher relationship quality and two forms of bullying victimization, namely relational and verbal victimization. We also examined the directionality of the relationship (e.g., whether student–teacher relationship quality predicted verbal and relational victimization, whether verbal and relational victimization predicted student–teacher relationship quality, or whether there were reciprocal relationships). When exploring these relationships, we utilized a social-ecological perspective focusing on the two in-school microsystems, namely the student–teacher relationship and the peer group and how the interaction between these two systems can affect relational and verbal victimization.

Our findings showed that both verbal and relational victimization was predicted by the quality of students’ relationships with their teachers. This pattern was displayed in both the positive and negative models showing that that the relationship quality to a greater extent predicts bullying victimization. This supports previous studies showing that positive student–teacher relationships predict less bullying victimization (Demol et al., 2020; Leadbeater et al., 2015; Serdiouk et al., 2016) and how an increase or decrease in the student-relationship quality also predict bullying victimization.

Thus, the results showed a significant effect of positive student–teacher relationship quality on later levels of bullying victimization. In other words, improved quality in student–teacher relationship over time predicted changes in bullying, where increases in positive relationship quality was associated with decrease s in bullying victimization, but only from fifth to sixth grade for relational victimization. Likewise, the increase in negative student–teacher relationship quality also increased bullying victimization, but only from fourth to fifth grade for relational victimization. In addition, our results also showed that bullying victimization can predict student–teacher relationship quality, mirroring the findings of Demol et al. (2020) and Leadbeater et al. (2015) but only for verbal victimization from fourth to fifth grade.

In terms of the longitudinal associations, the present study found a significant longitudinal association between student–teacher relationship quality and relational victimization in line with Demol et al.’s (2020) study. In addition, we found a significant longitudinal association between student-relationship quality and verbal victimization. To our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the longitudinal association between student-relationship quality and verbal victimization, the most common form of bullying (e.g., Kennedy, 2021; Waasdorp & Bradshaw, 2015). By focusing on verbal and relational victimization, the current study continues recent research on the relationship between the quality of the student–teacher relationship and various form of bullying to provide a more detailed understanding of these relationships. As our study shows how both relational and verbal victimization are associated with the quality of student–teacher relationship, type of victimization appears less important than victimization itself.

It should be noted, however, that several longitudinal associations tested were not significant in the current study; student–teacher relationship quality in fourth grade did not predict relational victimization in fifth grade and verbal victimization in fourth grade and relational victimization in fifth grade did not predict student–teacher relationship quality in fifth and sixth grades, respectively.

In contrast, all three measured constructs consistently predicted themselves and, were thus, stable over time. In other words, consistent with our hypothesis and previous longitudinal research (Choi & Park, 2021; Chu et al., 2018; Demol et al., 2022; Pouwels et al., 2016; Zych et al., 2020), we found moderate stability for bullying victimization. Consistent with our hypothesis and previous studies (e.g., Hajovsky et al., 2021; Harvey et al., 2022), the quality of the student–teacher relationship also predicted the subsequent quality of the student–teacher relationship. Moreover, students who scored higher on student–teacher relationship quality were less likely to be targets of verbal and relational bullying perpetration at each time point.

Our study also showed reciprocal longitudinal associations in both the positive and negative models between student–teacher relationship quality and verbal and relational bullying victimization. This means that the association can be reciprocal but that relationship quality to a greater extent predicts bullying victimization than bullying victimization predicts relationship quality.

One possible explanation to this reciprocal associations could be a more or less fixed or stable interplay between individual factors and contextual factors (cf., Bronfenbrenner, 1979) in schools (Hong & Espelage, 2012; Saarento et al., 2015). Examples of individual factors that may contribute to the maintenance of the pattern include personality traits and developmental trajectories of social cognitions, interpersonal skills, and social behaviors that differ across students. School contextual factors that may help explain our findings include established patterns of teacher expectations and classroom management, in whichteachers’s approach, treat and interact with students differently in the classroom (Emmer & Sabornie, 2015; Roland & Galloway, 2002; Saarento et al., 2015). Other possible school contextual factors might be the reciprocal links between student–teacher relationship quality, peer relationships and social behaviors (Endedijk et al., 2022) developed into stable patterns, including a long-term group structure, perceived popularity, peer preference, and a set of social roles and expectations in the classroom and peer groups (Pouwels et al., 2018; Saarento et al., 2015; Salmivalli, 2010). Differences in associations between verbal victimization and relational victimization might be that verbal victimizataion is easier to detect than more subtle bullying. Teachers might have difficulty supporting verbally victimized students when they exhibit social withdrawal, avoidance, or aggression (Leadbeater et al., 2015) that are related to and rooted in their victimization. If lower quality of the student–teacher relationship predicts greater victimization that in turn predicts lower quality of the student–teacher relationship, and so on, this more or less bidirectional longitudinal association becomes an indirect part of the so-called “victim cycle” that plays out in the peer ecology (Lyng, 2018) like a negative or downward spiral. In contrast, a healthy and protective cycle occurs when high quality student–teacher relationships predict less bullying victimization, which in turn predicts high student–teacher relationships, and so on, over time. Thus, our findings may shed light on teachers’ so-called “invisible hand” (Endedijk et al., 2022; Farmer et al., 2011), which can either increase or decrease the likelihood of students’ verbal and relational bullying experiences in school. However, only at one timepoint were the reciprocal association found between verbal and relational victimization and student–teacher relationship quality so we need to be catious when interpreting the findings.

From a social-ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), we can draw the conclusion based on our findings that teachers play an important role in a relatively stable yet changing mesosystem in which the interaction between the microsystem of the student–teacher relationship and the microsystem of the peer group influences bullying victimization (Bouchard & Smith, 2017). Our findings support the notion that a student’s relationship with their teachers is a significant microsystem in school (Bouchard & Smith, 2017; Farmer et al., 2011; see also Endedijk et al., 2022). Therefore, it is devastating for students who experience bullying that their victimization predicts poorer quality of the student–teacher relationship.

4.1 Limitations

Some limitations of this study should be mentioned. One limitation is that no mediating mechanisms were examined, such as peer-to-peer relationships, which could potentially explain the relationship between the quality of the student–teacher relationship and verbal and relational victimization. It is possible that, students who have poor relationships with their teachers also have poor relationships with their peers, which would likely increase their risk for verbal and relational victimization. In addition, the study was based on self-report, so there may be limitations in terms of memory, text comprehension. The use of self-reports also carries the risk of social desirability bias. To increase validity and to overcome potential problems due to shared variance, future studies should a more mixed data collection approach and consider self-report in combination with peer nominations and teacher reports in addition to self-reports. Moreover, the attrition analysis showed that students who dropped out after the first and second wave were victimized to a greater extent than those who continued their participation, thus suggesting that the missing data were not missing completely at random. However, the effect sizes of Cohen’s d were, however, negligible to small, suggesting that although the observed differences were statistically significant, their practical impact may be limited. Finally, we did not conduct any a priori power analysis to determine an appropriate sample size. Based on power calculations of other studies, however, it is reasonable to assume that our study had sufficient power to detect relatively small cross-lagged effects (Barzeva et al., 2020; Masselink et al., 2018).

4.2 Practical implications

These limitations aside, the study findings have implications for school-based anti-bullying practice. The current findings suggest that warm, caring and supportive student–teacher relationships are a key component of bullying prevention programs and efforts. Given the relationship between the quality of relationships with teachers and experiences of verbal and relational victimization found in the study, practitioners need to assess not only the quality of students’ relationships with their peers but also with their teachers. For students with poor relationship quality with their teachers, it is necessary for practitioners to not only work with students but also include teachers in treatment or intervention plans. Students who have negative and conflictual relationships with their teachers may lack social skills, which would likely spill over to their relations with their classmates and peers (Longbordi et al., 2022; Thornberg et al., 2017). Finally, it may be useful to incorporate awareness of the quality of the teacher-student relationship into teacher training to make them more aware of the role of the teacher-student relationship in the psychological adjustment of students in general and the risk of peer victimization in particular.

References

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Bardach, L., Yanagida, T., & Strohmeier, D. (2022). Revisiting the intricate interplay between aggression and preadolescents’ school functioning: Longitudinal predictions and multilevel latent profiles. Developmental Psychology, 58(4), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001317

Barzeva, S., Richards, J., Meeus, W., & Oldehinkel, A. (2020). The social withdrawal and social anxiety feedback loop and the role of peer victimization and acceptance in the pathways. Development and Psychopathology, 32(4), 1402–1417. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419001354

Behrhorst, K. L., Sullivan, T. N., & Sutherland, K. S. (2020). The impact of classroom climate on aggression and victimization in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 40(5), 689–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431619870616

Borntrager, C., Davis, J. L., Bernstein, A., & Gorman, H. (2009). A cross-national perspective on bullying. Child & Youth Care Forum, 38(3), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-009-9071-0

Bouchard, K. L., & Smith, J. D. (2017). Teacher-student relationship quality and children’s bullying experiences with peers: Reflecting on the mesosystem. Educational Forum, 81(1), 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2016.1243182

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist, 34(10), 844–850. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.844

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 993–1028). Wiley.

Casper, D. M., & Card, N. A. (2017). Overt and relational victimization: A meta-analytic review of their overlap and associations with social–psychological adjustment. Child Development, 88(2), 466–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12621

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Choi, B., & Park, S. (2021). Bullying perpetration, victimization, and low self-esteem: Examining their relationship over time. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(4), 739–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01379-8

Chouhy, C., Madero-Hernandez, A., & Turanovic, J. J. (2017). The extent, nature, and consequences of school victimization: A review of surveys and recent research. Victims & Offenders, 12(6), 823–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2017.1307296

Chu, X.-W., Fan, C.-Y., & Zhou, Z.-K. (2018). Stability and change of bullying roles in the traditional and virtual contexts: A three-wave longitudinal study in Chinese early adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(11), 2384–2400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0908-4

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cui, K., & To, S.-M. (2021). School climate, bystanders’ responses, and bullying perpetration in the context of rural-to-urban migration in China. Deviant Behavior, 42(11), 1416–1435. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2020.1752601

Demol, K., Leflot, G., Verschueren, K., & Colpin, H. (2020). Revealing the transactional associations among teacher-child relationships, peer rejection and peer victimization in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(11), 2311–2326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01269-z

Demol, K., Verschueren, K., Ten Bokkel, I. M., van Gils, F. E., & Colpin, H. (2022). Trajectory classes of relational and physical bullying victimization: Links with peer and teacher-student relationships and social-emotional outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(7), 1354–1373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01544-7

Deryol, R., & Wilcox, P. (2020). Physical health risk factors across traditional bullying and cyberbullying victim and offender groups. Victims & Offenders, 15(4), 520–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2020.1732510

Elledge, L. C., Elledge, A. R., Newgent, R. A., & Cavell, T. A. (2016). Social risk and peer victimization in elementary school children: The protective role of teacher-student relationships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(4), 691–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0074-z

Emmer, E. T., & Sabornie, E. J. (Eds.). (2015). Handbook of classroom management. Routledge.

Endedijk, H. M., Breeman, L. D., & van Lissa, C. J. (2022). The teacher’s invisible hand: A meta-analysis of the relevance of teacher–student relationship quality for peer relationships and the contribution of student behavior. Review of Educational Research, 92(3), 370–412. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211051428

Espelage, D. L., Hong, J. S., Rao, M. A., & Thornberg, R. (2015). Understanding ecological factors associated with bullying across the elementary to middle school transition in the United States. Violence and Victims, 30(3), 470–487. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-14-00046

Farmer, T. W., McAuliffe Lines, M., & Hamm, J. V. (2011). Revealing the invisible hand: The role of teachers in children’s peer experiences. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(5), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2011.04.006

Frisén, A., Holmqvist, K., & Oscarsson, D. (2008). 13-year-olds’ perception of bullying: Definitions, reasons for victimisation and experience of adults’ response. Educational Studies, 34(2), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690701811149

Fry, D., Fang, X., Elliott, S., Casey, T., Zheng, X., Li, J., Florian, L., & McCluskey, G. (2018). The relationships between violence in childhood and educational outcomes: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 75, 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.021

Hajovsky, D. B., Chesnut, S. R., Helbig, K. A., & Goranowski, S. M. (2021). On the examination of longitudinal trends between teacher–student relationship quality and social skills during elementary school. School Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1883995

Hallinan, M. T. (2008). Teacher influences on students’ attachment to school. Sociology of Education, 81(3), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070808100303

Harvey, E., Lemelin, J.-P., & Déry, M. (2022). Student-teacher relationship quality moderates longitudinal associations between child temperament and behavior problems. Journal of School Psychology, 91, 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2022.01.007

Hellström, L., Thornberg, R., & Espelage, D. L. (2021). Definitions of bullying. In P. K. Smith & J. O’Higgins Norman (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of bullying. A comprehensive and international review of research and intervention (pp. 3–21). Wiley-Blackwell.

Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(4), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003

Hong, I. K., Wang, W., Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. M. (2020). Peer victimization through a trauma lens: Identifying who is at risk for negative outcomes. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12488

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Iotti, N., Thornberg, R., Longobardi, C., & Jungert, T. (2020). Early adolescents’ emotional and behavioral difficulties, student–teacher relationships, and motivation to defend in bullying incidents. Child & Youth Care Forum, 49(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09519-3

Jungert, T., Piroddi, B., & Thornberg, R. (2016). Early adolescents’ motivations to defend victims in school bullying and their perceptions of student–teacher relationships: A self-determination theory approach. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.09.001

Kennedy, R. S. (2021). Bullying trends in the United States: A meta-regression. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(4), 914–927. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019888555

Kert, A. S., Codding, R. S., Tryon, G. S., & Shiyko, M. (2010). Impact of the word “bully” on the reported rate of bullying behavior. Psychology in the Schools, 47(2), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20464

Krause, A., & Smith, J. D. (2022). Peer aggression and conflictual teacher-student relationships: A meta-analysis. School Mental Health, 14(2), 306–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09483-1

Leadbeater, B., Sukhawathanakul, P., Smith, D., & Bowen, F. (2015). Reciprocal associations between interpersonal and values dimensions of school climate and peer victimization in elementary school children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(3), 480–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.873985

Lin, S., Fabris, M. A., & Longobardi, C. (2022). Closeness in student–teacher relationships and students’ psychological well-being: The mediating role of hope. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 30(1), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/10634266211013756

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press.

Longobardi, C., Ferrigno, S., Gullotta, G., Jungert, T., Thornberg, R., & Marengo, D. (2022). The links between students’ relationships with teachers, likeability among peers, and bullying victimization: The intervening role of teacher responsiveness. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 37(2), 489–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00535-3

Longobardi, C., Settanni, M., Lin, S., & Fabris, M. A. (2021). Student–teacher relationship quality and prosocial behaviour: The mediating role of academic achievement and a positive attitude towards school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(2), 547–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12378

Lyng, S. T. (2018). The social production of bullying: Expanding the repertoire of approaches to group dynamics. Children & Society, 32(6), 492–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12281

Marengo, D., Fabris, M. A., Prino, L. E., Settanni, M., & Longobardi, C. (2021). Student-teacher conflict moderates the link between students’ social status in the classroom and involvement in bullying behaviors and exposure to peer victimization. Journal of Adolescence, 87, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.01.005

Masselink, M., Van Roekel, E., Hankin, B. L., Keijsers, L., Lodder, G. M. A., Vanhalst, J., Verhagen, M., Young, J. F., & Oldehinkel, A. J. (2018). The longitudinal association between self-esteem and depressive symptoms in adolescents: Separating between-person effects from within-person effects. European Journal of Personality, 32(6), 653–671. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2179

Pouwels, J. L., Lansu, T. A. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2018). A developmental perspective on popularity and the group process of bullying. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 43, 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.10.003

Pouwels, J. L., Souren, P. M., Lansu, T. A. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2016). Stability of peer victimization: A meta-analysis of longitudinal research. Developmental Review, 40, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.01.001

Quin, D. (2017). Longitudinal and contextual associations between teacher–student relationships and student engagement: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 345–387. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316669434

Rambaran, J. A., Dijkstra, J. K., & Veenstra, R. (2020). Bullying as a group process in childhood: A longitudinal social network analysis. Child Development, 91(4), 1336–1352. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13298

Roland, E., & Galloway, D. (2002). Classroom influences on bullying. Educational Research, 44(3), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188022000031597

Roorda, D. L., Jak, S., Zee, M., Oort, F. J., & Koomen, H. M. (2017). Affective teacher–student relationships and students’ engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. School Psychology Review, 46(3), 239–261. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0035.V46-3

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more Version 05–12 (BETA). Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Saarento, S., Garandeau, C. F., & Salmivalli, C. (2015). Classroom- and school-level contributions to bullying and victimization: A review. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25(3), 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2207

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

Schoeler, T., Duncan, L., Cecil, C. M., Ploubidis, G. B., & Pingault, J.-B. (2018). Quasi-experimental evidence on short- and long-term consequences of bullying victimization: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 144(12), 1229–1246. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000171

Selig, J. P., & Little, T. D. (2012). Autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis for longitudinal data. In B. Laursen, T. D. Little, & N. A. Card (Eds.), Handbook of Developmental Research Methods (pp. 265–278). The Guilford Press.

Serdiouk, M., Berry, D., & Gest, S. D. (2016). Teacher-child relationships and friendships and peer victimization across the school year. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 46, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.08.001

Sijtsema, J. J., Rambaran, J. A., Caravita, S. C. S., & Gini, G. (2014). Friendship selection and influence in bullying and defending: Effects of moral disengagement. Developmental Psychology, 50(8), 2093–2104. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037145

Sjögren, B., Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Gini, G. (2021). Bystander behaviour in peer victimisation: Moral disengagement, defender self-efficacy and student-teacher relationship quality. Research Papers in Education, 36(5), 588–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1723679

Sulkowski, M. L., & Simmons, J. (2018). The protective role of teacher–student relationships against peer victimization and psychosocial distress. Psychology in the Schools, 55(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22086

Swearer, S. M., & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis–stress model. American Psychologist, 70(4), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038929

Swedish National Agency for Education. (2022). Sök statistik [Search statistics]. https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/sok-statistik-om-forskola-skola-och-vuxenutbildning?sok=SokA

ten Bokkel, I. M., Roorda, D. L., Maes, M., Verschueren, K., & Colpin, H. (2023). The role of affective teacher–student relationships in bullying and peer victimization: A multilevel meta-analysis. School Psychology Review, 52(2), 110–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2029218

ten Bokkel, I. M., Verschueren, K., Demol, K., van Gils, F. E., & Colpin, H. (2021). Reciprocal links between teacher-student relationships and peer victimization: A three-wave longitudinal study in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(11), 2166–2180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01490-4

Thornberg, R., Hammar Chiriac, E., Forsberg, C., & Wänström, L. (2023). The association between student-teacher relationship quality and school liking: A small-scale 1-year longitudinal study. Cogent Education, 10(1), 2211466. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2211466

Thornberg, R., Wegmann, B., Wänström, L., Bjereld, Y., & Hong, J. S. (2022). Associations between student-teacher relationship quality, class climate, and bullying roles: A Bayesian multilevel multinomial logit analysis. Victims & Offenders, 17(8), 1196–1223. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2022.2051107

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Hymel, S. (2019). Individual and classroom social-cognitive processes in bullying: A short-term longitudinal multilevel study. Frontiers in Psychology, 31, 1752. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01752

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Jungert, T. (2018). Authoritative classroom climate and its relations to bullying victimization and bystander behaviors. School Psychology International, 39(6), 663–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034318809762

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Pozzoli, T. (2017). Peer victimisation and its relation to class relational climate and class moral disengagement among school children. Educational Psychology, 37(5), 524–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2016.1150423

Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(5), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.002

Waasdorp, T. E., Fu, R., Clary, L. K., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2022). School climate and bullying bystander responses in middle and high school. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 80, 101412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2022.101412

Woods, S., & Wolke, D. (2003). Does the content of anti-bullying policies inform us about the prevalence of direct and relational bullying behaviour in primary schools? Educational Psychology, 23(4), 381–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410303215

Yoon, J., Bauman, S., & Corcoran, C. (2020). Role of adults in prevention and intervention of peer victimization. In L. H. Rosen, S. R. Scott, & S. Y. Kim (Eds.), Bullies, Victims, and Bystanders (pp. 179–212). Palgrave Macmillan.

Zych, I., Tfofi, M. M., Llorent, V. J., Farrington, D. P., Ribeaud, D., & Eisner, M. P. (2020). A longitudinal study on stability and transitions among bullying roles. Child Development, 91(2), 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13195

Funding

Open access funding provided by Linköping University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Forsberg, C., Sjögren, B., Thornberg, R. et al. Longitudinal reciprocal associations between student–teacher relationship quality and verbal and relational bullying victimization. Soc Psychol Educ 27, 151–173 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09821-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09821-y