Abstract

Students face frequent formal and informal tests, both in the academic context and social life. On each of these occasions, they risk falling short of their own or others’ expectations. Facing failure is a psychological challenge, and people can react with defensive strategies, which may have negative consequences. Here we investigated the role of self-esteem as a possible buffer against these defensive strategies. Previous research has demonstrated that, in the face of failure, individuals with discrepant (fragile: high explicit and low implicit, or damaged: high implicit and low explicit) self-esteem are more likely to engage in defensive mechanisms than individuals with consistent implicit and explicit self-esteem. Two studies investigate the relationship between implicit and explicit self-esteem and two defensive strategies against the threat of failure: subjective overachievement and retroactive excuses. In Study 1 (N = 176 high school students), we find an association between fragile self-esteem and subjective overachievement. In Study 2 (N = 101 university students), damaged self-esteem is related to the increased use of retroactive excuses as a form of self-serving bias. These results add to the growing body of evidence documenting the maladaptive nature of fragile and damaged self-esteem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In everyday life, students encounter many situations where they are put to the test. The educational settings are characterized by learning assessments. In social interactions, adolescents and emerging adults have to try out and refine their social skills. At times, their performance falls short of their expectations and wishes or those others set out for them. Facing failure is a challenge, both from the practical and psychological perspectives. For instance, a student who fails an exam has to form a strategy to achieve a better level of preparation and manage the possible implication of the result for self-evaluation. Indeed failing, or performing below one’s expectations, can influence mood, affect, and emotional states (Nummenmaa & Niemi, 2004), threaten the sense of self-worth (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001), and is associated with adverse outcomes in psychological well-being in the longer term: Longitudinal studies connect failure at younger ages with clinical depression in adulthood (McCarty et al., 2008), and important failures on one’s job may engender adverse reactions such as shame and anxiety, enhancing the risk of further mistakes (Sirriyeh et al., 2010).

An unfavorable outcome that might suggest a lack of valuable skills poses a threat to self-esteem and to the self-enhancement motive, which is the motivation to maintain, boost, and preserve a positive self-view (Sedikides & Gregg, 2008). A person can enact various defensive strategies for self-protection against the negative psychological consequences of failure (Campbell & Sedikides, 1999; Cramer, 2015; Oleson et al., 2000). The present research investigates the relationship between defense strategies and self-esteem. Self-esteem is an interpersonal difference dimension particularly relevant to reactions to failure and negative feedback. To give a few recent examples, Beekman and colleagues (2017) investigated a sample of young adult women. They found that the negative impact of social rejection on affect and restrictive eating was increased for participants with lower self-esteem levels. Similarly, Tobia and colleagues (2017) showed that, after social exclusion, children with lower relational self-esteem scores performed worse on a logical reasoning task.

The study focuses on defensive strategies to deal with the request to succeed, with samples of adolescents and emerging adults. Adolescence, the life stage between childhood and adulthood, commonly situated between 10 and 20 years of age (and expanded adolescence between 10 and 25 years; Sawyer et al., 2018), is characterized by biological maturation and social role transition. One of its main tasks is to develop a clear identity, which is closely related to well-being (Branje, 2022). The subsequent phase of emerging adulthood, mainly between 18 and 29 years old, transitions into adulthood. These two developmental stages are characterized by changes and instability (Arnett, 2014; Maree & Twigge, 2016). Adolescents and emerging adults have to make important choices, and often experience confusion, stress, and uncertainty; these life stages are characterized by an increase of psychological difficulties such as anxiety and impaired self-esteem (Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2018). Emerging adults' difficulties in defining themselves negatively impact their psychosocial well-being (Baggio et al., 2017). In these stages of life, the request to be successful can be particularly exacting, as individuals deal with the challenges of forming a coherent sense of identity and building positive self-esteem and self-efficacy (Arnett, 2014; Erol & Orth, 2011; Porfeli & Lee, 2012; Schunk & Meece, 2006; Schwarz et al., 2010). Moreover, adolescents confront frequent occasions in which their abilities are subjected to verification and there is the risk of failure. In education settings, students face graded interrogations and tests; moreover, the occasions where they have to speak in front of the class or teachers ask questions can be perceived as situations in which their skills are challenged. Furthermore, they must develop new social competencies and try them out in the social arena, at the risk of doing or saying the wrong thing in front of their peers. Especially in these life stages, inadequate strategies to cope with actual or feared failures hinder the possibility of solving one’s self-doubts and forming a solid sense of one’s abilities. This interferes with the critical task of identity formation (Becht et al., 2021). These are also phases where practitioners and educators most probably have more room for intervention than in subsequent moments of life. A better understanding of the characteristics and correlates of defensive strategies at such ages of life can increase theoretical knowledge. Perhaps more importantly, it can help identify individuals at higher risk of coping inadequately with failure and develop interventions to support them in forming more adequate strategies.

1.1 Self-esteem and self-esteem discrepancies

Self-esteem has been defined in various ways, mostly having a common core in the idea that it consists of an evaluation of oneself and in the sense of one’s self-worth. Initially, self-esteem was typically conceived as a unitary concept, but various authors have recently proposed that it may have different manifestations (Carraro et al., 2013). The differentiation between implicit and explicit self-esteem has proven particularly useful. This perspective distinguishes between a more controlled evaluation of one’s self-worth based on an intentional self-appraisal (i.e., explicit self-esteem—ESE) and a more spontaneous affective reaction toward the self (i.e., implicit self-esteem—ISE). ESE is typically investigated through self-reported questionnaires, such as the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965). ISE is generally assessed through associative measures like the Implicit Association Test (Greenwald & Farnham, 2000) or spontaneous evaluations of stimuli associated with the self, most notably the initials of one’s name in the Name Letter Task (NLT; Lebel & Gawronski, 2009). Implicit and explicit expressions of self-esteem can be inconsistent (Zeigler-Hill & Jordan, 2010; Zeigler-Hill et al., 2011a, 2011b), which is considered maladaptive (Schröder-Abé et al., 2007a, 2007b). Some individuals describe themselves in highly favorable terms in controlled self-evaluations. Still, their spontaneous reactions suggest a less positive implicit self-esteem: Their self-esteem is considered fragile, insecure, and vulnerable to threat. This personality setup is associated with unrealistic optimism and an idealized self-view (Bosson et al., 2003), and with an increased tendency to process threatening information with anger and hostility, which is considered a defensive reaction (Kernis et al., 2008). There is substantial agreement that people with fragile self-esteem are more easily threatened by failure and less readily accept their bad qualities than individuals with secure high self-esteem (Bosson et al., 2003).

The other situation of inconsistency is when individuals hold low ESE and high ISE, or in other words, show a lower than average self-regard in responses to questionnaires but display high positivity in their automatic reactions to the self-concept. This condition, labeled damaged self-esteem, is thought to be present in individuals who initially had high self-esteem but could not meet their high self-expectations and, therefore, lowered their conscious self-regard. This inconsistent self-esteem pattern has been related to enhanced defensiveness (Schröder-Abé et al., 2007a, 2007b).

1.2 Self-esteem inconsistencies and reactions to failure

Facing a failure, or a difficult situation that could result in failure, is demanding for anyone, but solid self-esteem can help. Indeed, the ability to react to failure without being excessively conditioned indicates robust self-esteem (Lobel & Teiber, 1994; McFarlin & Blascovich, 1981). In front of a difficult task or negative feedback, individuals with secure high self-esteem will perceive the situation as a challenge (Seery et al., 2004), which requires commitment but can become a success. Even if the outcome is not the success one expects, they can cope with the negative intrusive thoughts associated with an ego threat (Borton et al., 2012). Therefore, we can expect individuals with consistent high self-esteem to cope with negative outcomes, or the risk of future failure, without heavy use of defensive strategies.

For those characterized by fragile self-esteem, on the contrary, failure constitutes a threat (Seery et al., 2004), a disruptive event, harder to cope with (see also Zeigler-Hill et al., 2011a, 2011b). They will probably anticipate succeeding as they have a positive view of themselves in their more controlled reasoning, at a more reflective level. Still, their less positive spontaneous self-reactions may color their expectations with a shade of insecurity; the possibility of unfavorable results is a threat, as a failure would confirm their spontaneous insecurities. Therefore, we can expect that, in the face of challenging situations, individuals with fragile self-esteem take a more defensive position than those with solid self-esteem.

Persons with damaged self-esteem might have trouble dealing with difficult situations too, but for different reasons: These individuals hold a high expectation to fail, in line with their explicit low self-esteem. But, linked to the implicit high self-esteem, a 'grain of hope' remains: They still harbor the wish of succeeding and restoring a positive explicit view of themselves (Jordan et al., 2003), and interpret ambiguous feedback about themselves more positively (Schröder-Abé et al., 2007a, 2007b). Therefore, even if expected, the experience of failure will still hurt. Accordingly, it is plausible that these people will avoid challenging situations and adopt a defensive approach towards these situations. In line with this reasoning, individuals with damaged self-esteem show higher self-enhancement (Bosson et al., 2003) and higher defensiveness (Jordan et al., 2003).

Finally, individuals with consistent low self-esteem will not have high expectations of success (Lane et al., 2004). However, they will not fear the possible failure they envisage as a result of the task, as this is consistent with their spontaneous reactions. For this reason, we can expect consistent low self-esteem persons not to enact pronounced defensive dynamics.

In sum, it is plausible that people with incoherent self-esteem show more defensive responses to failures and challenging tasks, even though for different reasons. This expectation is consistent with the literature suggesting that self-serving biases are stronger when self-evaluations are discrepant (Kernis, 2000). This notion has been supported by empirical evidence showing that inconsistency between ISE and ESE was related to various defensive mechanisms as, for example, giving more importance to those attributes that the individual believes to possess (Kernis et al., 2005), increased outgroup derogation (Kernis et al., 2005), positive reactions to ambiguous statements and more superficial examination of negative feedback (Schröder-Abé et al., 2007a, 2007b). Both fragile/insecure self-esteem and damaged self-esteem are related to defensive responses (Bosson et al., 2003; Kernis et al., 2008; Schröder-Abé et al., 2007a, 2007b).

1.3 Discrepant self-esteem and defensive strategies in adolescence and emerging adulthood

Empirical evidence on the correlates of discrepant self-esteem in adolescence is sparse. It has been shown that discrepant self-esteem during adolescence relates to various important outcomes, including aggression (Sandstrom & Jordan, 2008) and social anxiety (Schreiber et al., 2012; van Tuijl et al., 2014). This evidence shows that discrepancies in self-esteem are, at the very least, a sign of difficulty in this critical developmental stage.

Adolescents often cope with failures and challenging tasks with self-serving strategies, like self-handicapping (Midgley et al., 1996; Yu & McLellan, 2019) and procrastination (Klassen et al., 2009).The existing knowledge of the relationship between self-esteem discrepancies and self-defensive strategies in adolescents is limited, and we must rely mostly on studies conducted with adult participants. However, in considering such strategies, the individual’s age is an important factor (Cramer, 2015), as individuals’ level of cognitive sophistication varies with the development stage, and so does the structure of self-knowledge. We aim to address this gap in research by investigating the relationship between discrepancies and self-defensive strategies in adolescence and emerging adulthood.

It is plausible that adolescents and emerging adults with low self-esteem make greater use of defensive strategies to cope with failure. Apparently contradicting this expectation, some empirical evidence suggests that adolescents with very high levels of self-esteem make excessive use of defensive strategies. For example, Robins and Beer (2001) showed that students with very high self-reported self-esteem reacted with a discounting strategy to the contradictory evaluations of their teachers, in order to maintain their positive self-view. It is conceivable, however, that this pattern of reactions is the consequence of fragile self-esteem, or in other words, the students resorted to the protective strategy because a consistent spontaneous sense of self-worth did not support their grandiose explicit self-view. More research is, therefore, needed to understand the relationship between self-esteem discrepancies and defensive strategies.

The present research focuses on two defensive strategies: subjective overachievement (i.e., a preventive strategy focalized on the avoidance of failure; Oleson et al., 2000), and the use of self-serving biases (i.e., retroactively explaining failure away once it has occurred; Campbell & Sedikides, 1999, p. 23). Both strategies have the negative side-effect of limiting the possibility of self-knowledge and can therefore be particularly harmful for the identity formation task that characterizes adolescence and emerging adulthood (Becht et al., 2021), where self-doubt can have significant life consequences (Porfeli & Lee, 2012).

1.4 Subjective overachievement, concern with performance and self-doubt

Subjective overachievement is a tendency to be highly concerned to always have good performances because of the implications that success and failure have for one’s competencies and self-worth, associated with doubts about possessing the abilities required by the situation (Oleson et al., 2000). For subjective overachievers, success is the measure of their worth and the demonstration of their talent. They fear the negative implications that failure could have for their abilities, both in terms of their sense of self-worth and the impressions they give to others. Therefore, they protect themselves from failure by spending extraordinary effort on the task. For instance, a student might react to the fear of a written test by studying for an exceptionally high amount of time, learning by heart every single line of the book, and rehearsing the materials repeatedly. The result would hopefully be a good note, and the relevant others (parents, teachers, peers) would not think that s/he lacks the relevant academic competencies. However, this overstudying comes with a cost for self-knowledge: This excessive outflow of effort in the task renders performance less informative regarding one’s abilities, because success can be explained away by the exceptional effort; therefore, it perpetuates self-doubt (Wichman & Hermann, 2010). In such a way, the strategy of subjective overachievement creates difficulties in gathering important information about one’s strengths and weaknesses and confidence in one’s abilities.

Oleson and colleagues (2000) have developed a scale to measure subjective overachievement, which allows assessing two distinct dimensions: concern with performance and self-doubt. The concern with performance subscale tackles the tendency of subjective overachievers to strongly desire to obtain good results and their belief that it is important to always succeed and never fail. According to Oleson and colleagues (2000), this tendency is based on the conviction that one’s performance demonstrates one’s worth and their concern for how one’s performance appears to others; for individuals with high concern with performance, success is a signal to others that they are competent, worthy people.

The self-doubt subscale measures unsureness about one’s competencies and self-worth. Self-doubt does not imply the belief of being incapable of performing specific tasks: It can be better described as insecurity regarding one’s level of competence. As stated by Braslow and colleagues (2012, p. 472): “chronically self-doubting individuals might be viewed as having a wide confidence interval around judgments of their ability.” It is normal to experience self-doubt sometimes, but chronic self-doubt is problematic and negatively related to well-being. It is related to enhanced sensitivity to the implications of one’s results, which can negatively impact performance by diverting attention from the task and focusing it on the self (Braslow et al., 2012). Self-doubt is thought to trigger self-defensive strategies to cope with challenging tasks, most notably self-handicapping and overachieving.

1.5 Retroactive excuses

Another way to deal with external feedback about failure is by resorting to explanations that retroactively discredit either the performance or the task as not indicative of one’s true abilities. This can be accomplished by producing excuses for why the current performance was not representative of one’s real ability or discounting the task as unable to detect relevant skills. These explanations fall in the broader concept of self-serving bias, which refers to “external attributions for outcomes that disfavor the self but internal attributions for outcomes that favor the self” (Campbell & Sedikides, 1999, p. 23). Self-serving attributions are thought to be motivated by the individuals’ need to protect or enhance their self-esteem (Mezulis et al., 2004). Research has generally evidenced a positive relationship between self-serving bias and self-esteem (Mezulis et al., 2004). Still, specific and more problematic self-serving biases might be characteristic of individuals with low self-esteem. Schütz (1998) found that, when reporting negative autobiographical accounts, individuals with high self-esteem focussed more on the behavior to reframe it as less negative, while those characterized by low self-esteem more often resorted to external attributions (we might say that they made excuses). Similarly, using a questionnaire to measure the tendency to use proactive and retroactive excuses, Maltese and colleagues (2012) found a low negative correlation between questionnaire measures of self-esteem and of the use of retroactive justifications (e.g., “In front of a failure, you can say that the test is too difficult”), in a large sample of high-school students. These excuses allow discounting the feedback received as irrelevant to one’s abilities and may lead to psychological disengagement (Beaton et al., 2015; Casad et al., 2019; Loose et al., 2012; Major & Schmader, 1998; Schmader et al., 2001), which in turn can have important psychological and behavioral implications. Similar to subjective overachievement, these latter self-serving biases are also related to costs in objective appraisal and knowledge of one’s strengths and weaknesses.

In sum, subjective overachievement and self-serving retroactive excuses are dysfunctional strategies to avoid negative performances influencing one’s sense of self-worth and how others evaluate one’s abilities. In subjective overachievement, this goal is pursued by trying to avoid failure at any cost. When retroactive excuses are used, it is pursued by explaining away the failure once it has happened. Importantly, both associate the protection of the self-image with costs in self-knowledge and may interfere with the discovery of one’s abilities as they obscure the connection between performance and competency.

1.6 Purpose of the present research and hypotheses

Previous research has evidenced that both fragile/insecure self-esteem and damaged self-esteem are related to defensive responses (Bosson et al., 2003; Kernis et al., 2008; Schröder-Abé et al., 2007a, 2007b). No study, however, has explored the relation between self-esteem inconsistencies and the two defensive strategies of subjective overachievement and self-serving attributions. The excessive use of these two strategies can damage the developmental task of self-knowledge construction that characterizes adolescence and emerging adulthood (e.g., Beaton et al., 2015; Wichman & Hermann, 2010). We, therefore, conducted two correlational studies to test the hypothesis that the use of these strategies is higher in individuals characterized by inconsistent self-esteem, with a sample of adolescents and one of emerging adults.

2 The research

In Study 1, in a sample of adolescents, we investigated how ESE, ISE, and their interplay, related to general tendencies to subjective overachievement. Next, in Study 2, we moved the focus from general defensive reactions to specific defensive attributional biases after a specific situational failure; we investigated a sample of emerging adults who received negative feedback regarding their ability to solve a logical task and put their measured ESE, ISE, and their interplay, in relation with self-serving attributions to this feedback.

The data are openly available here: https://osf.io/vmtc6/.

3 Study 1

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

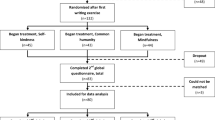

We contacted a total of 204 students enrolled in two Italian state high schools, one with an artistic curriculum (n = 107) and the other with a differentiated range of course options (scientific, linguistic, business, management, tourism, and geometers curricula; n = 93). In the case of minors, also their parents provided informed consent to their children’s participation in the study. In four cases, we did not receive the parents’ or the student’s consent, and two students could not complete the study for time reasons. The final sample consists of 198 Italian adolescents (75.77% female, mean age 17.55 years, SD = 1.51) who volunteered to participate in this study. The size of the sample is based on convenience reasons. We conducted a sensitivity analysis with G*Power (Faulet al., 2007), with significance level α = 0.0125Footnote 1 and power (1 − β) = 0.80. This analysis indicated that our sample size (N = 169 after exclusion of 21 participants who did not provide usable data on the NLT, and 8 participants with very extreme values, see Results section) was adequate for the detection of correlations equal or greater to |r|= 0.25, which is considered medium size. A second sensitivity analysis, with significance level α = 0.025 (also in this case we implemented a Bonferroni correction because we tested two different criteria of defensive mechanisms), power (1 − β) = 0.80, based on the F-test family for multiple regression with three predictors, with N = 169 (based on the sample on which the analysis was performed) indicated that we had an adequate level of power for an effect size of f2 = 0.08 or superior, which is considered medium (Cohen, 1992).

3.1.2 Measures

Implicit Self Esteem. As we needed a paper-and-pencil measure of ISE, we chose the NLT, which had proven useful in previous research, providing converging results with the more widely used IAT (e.g., Maroiu et al., 2016). We presented participants the NLT, in which they rated the letters from A to Z, in a fixed random order, on 10-point scales from 1 (I don’t like it at all) to 10 (I like it very much). We chose a 10-point scale to make it more similar to the Italian school evaluation system, which uses marks from 1 to 10, where 10 is the best result. We computed ISE scores with the I-algorithm (LeBel & Gawronski, 2009) that corrects both for differences in normative pleasantness of the letters and individual differences in baseline response tendencies in letter ratings. Higher scores indicated higher ISE.

Explicit Self Esteem. We used the Italian translation of the RSES (Prezza et al., 1997). Participants evaluated each of the RSES sentences on a 6-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The RSES is a widely used self-report measure of global trait Self Esteem and contains an equal number of positively (e.g., “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”) and negatively worded items (e.g., “At times I think I am no good at all”). We computed ESE as the summed score of the responses after reverse scoring the negatively worded items. Higher scores indicated higher levels of ESE.

Self-doubt and Concern with Performance. We presented participants with the Subjective Overachievement Scale (SOS; Oleson et al., 2000; translated in Italian for the present research), a 17-item questionnaire that includes two independent subscales: concern with performance and self-doubt. The Concern with Performance subscale consists of nine statements addressing the beliefs regarding the concepts of success and personal failure that underly the subjective overachievement tendency (e.g., “It is important that I succeed in all that I do; I try to avoid being too successful”). The self-doubt subscale consists of eight statements about the perception of one's own value and competence. These refer to the general sense of being unsure about one’s capabilities and the desire to avoid adverse outcomes, without any specific reference to coping strategies (e.g., “More often than not, I feel unsure of my abilities”). Participants evaluated each SOS sentence on a 6-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

3.1.3 Procedure

We initially contacted the high school principal, described the aims of the research and asked for approval to conduct the study. The school provided the students’ parents with a brief description of the study aims and a request for their child’s consent. The researchers subsequently administered the questionnaires during ordinary lessons. The teachers were present for supervision but did not intervene in the study administration. In class, we informed the students that the questionnaire consisted of aesthetical judgments, questions on how they faced life, and their attitudes and beliefs regarding alcohol. They provided their consent in study participation and completed a paper and pencil questionnaire composed of the measures described above, in the following order: the NLT, the RSES, and the SOS. Next, we presented participants with a questionnaire on alcohol consumption, unrelated to the scopes of the present research. In the end, we asked respondents to report their age, gender, and the first two initial letters of the given name. For the students to feel their privacy protected, we did not ask for the initial of their surname. After participants had completed the questionnaire, they received a brief verbal explanation of the study and had the opportunity to ask questions.

3.1.4 Hypotheses

We expected that self-esteem discrepancies would be related to the Concern with performance subscale of the Subjective Overachievement Scale, as this subscale directly tackles the individual’s stance towards success and failure. More specifically, we expected higher discrepancies to be associated with higher scores on this subscale. As concerns the subscale of self-doubt, previous research has evidenced a relatively high negative correlation between self-doubt and ESE (Duru et al., 2014; Oleson et al., 2000). We, therefore, hypothesized to replicate this correlation. Furthermore, we deemed it worth exploring its connection with ISE and the ISE-ESE interplay.

3.1.5 Data analyses

We used the 2-Median Absolute Deviations rule (2-MAD; Reimann et al., 2011) to identify outliers in our implicit and explicit self-esteem data. Next, we used principal components analysis (PCA) to investigate the internal validity of the scales used for assessing our criterion variables. We used parallel analysis and scree plot analysis to determine the optimal number of factors.

Finally, we analyzed our data using hierarchical stepwise regression analysis, which is frequently used in the literature on implicit-explicit self-esteem discrepancies (e.g., Maroiu & Maricutoiu, 2016). First, we transformed all raw scores into standardized scores (z-scores) and entered both self-esteem forms as predictors. Next, we used the medmod module (Selker, 2017) in the jamovi (The jamovi project, 2021) software to test our hypotheses regarding the moderation effects. In this stage, the software automatically computed the cross-product vector of the two standardized predictors and presented the regression equation with three predictors (i.e., the two forms of self-esteem and their interaction). If the cross-product vector of the two forms of self-esteem was a significant predictor, we conducted a simple slope analysis in which we estimated the relationships between explicit self-esteem and the criterion at different levels of implicit self-esteem (i.e., ± 1 SD).

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Preliminary analyses

Twenty-one participants did not evaluate one or more letters in the NLT, and one did not report the initial letter of their name (15 participants failed to evaluate one letter, two participants failed to evaluate two letters, one participant three letters, and three participants evaluated none of the letters). We eliminated the data of these participants from the analysis, leaving us with a sample of N = 176 participants.

We computed the internal consistency of the self-report scales (see Table 1). The RSES showed adequate internal consistency. The Self Doubt subscale of SOS showed acceptable internal consistency, and the PCA indicated that this subscale had a single component structure. For the Concern with Performance subscale, the PCA indicated two orthogonal components (oblimin rotation showed a correlation of r = .215 between the two components). One dimension included items describing success avoidance and discomfort with success (“There are some situations where I think it is better that I fail,” “I think that in some situations it is important that I not succeed,” “Sometimes I am more comfortable when I lose or do poorly,” and “I try to avoid being too successful”). We interpreted it as indicating psychological disengagement, which is a strategy opposite to subjective overachievement, as it consists in withdrawing one’s effort from a field to protect one’s psychological well-being (Osborne, 1997; Osborne & Rausch, 2001). The other dimension included items more clearly related to the beliefs in the necessity of success that characterize Psychological Overachievement (“Failure is unacceptable to me,” “It is important that I succeed in all that I do,” “I strive to be successful at all times,” “For me, being successful is not necessarily the best thing” (R). We deemed the internal consistency of these two components acceptable (Hair et al., 2010; Nunnally, 1967), considering that they were based on a restricted number of items, and computed the summed scores for these two components.

Based on the 2-MAD rule and the subsequent visual inspection of the histogram of frequencies, we detected five outliers for the variable ISE and three for the variable ESE, each distant from the median more than five MADs. These data were eliminated from the analysis listwise, leaving a final sample of 169 participants. Table 1 reports the main descriptive statistics and correlations between the variables.

3.2.2 Relationship between self-esteem and defensive strategies

We investigated the relationship between ISE, ESE, their interplay, and the three criteria: self-doubt, overachievement beliefs, and psychological disengagement. As indicated in Table 2, self-doubt was significantly associated with ESE, β = -0.61, t(166) = -9.83, p < .01, but no significant relationship emerged with ISE, β = 0.06, t(166) = 0.84, p = .40, and ESE*ISE interaction, β = 0.04, t(166) = 0.56, p = .58. Consistent with previous literature, the higher the ESE score, the lower the level of self-doubt. Disengagement, on the other hand, showed a negative association with ISE, β = -0.16, t(166) = .2.01, p = .04, which might suggest that implicit self-esteem might, indeed, be a protective factor against this possible negative reaction to failure; however, with the Bonferroni correction for multiple testing, this association was not significant. No relationship emerged between disengagement and either ESE, β = 0.04, t(166) = 0.42, p = .68, or the ESE * ISE interaction, β = -0.03, t(166) = -0.32, p = .75.

For subjective overachievement beliefs, ESE revealed a significant effect in Step 1, indicating that higher overachievement scores accompanied higher levels of ESE. In contrast, ISE was not significantly associated with this criterion in Step 1. The relation between subjective overachievement and ESE was positive, β = 0.18, t(167) = 2.41, p = .02, indicating that higher self-reported self-esteem scores were associated with higher overachievement. At first glance, this result might seem counter-intuitive. However, in Step 2, a significant ESE*ISE interaction effect emerged that helped clarify it, β = -0.21, t(166) = -2.54, p = .01. Indeed, a simple slope analysis indicated that ESE was significantly related to overachievement for participants with low levels of ISE (1 SD below the mean), β = 0.39, t(165) = 3.75, p < .01, and for participants with average levels of ISE, β = 0.18, t(165) = 2.36, p = .02. On the other hand, for participants with higher ISE scores (1 SD above the mean), no significant relation between ESE and overachievement emerged, β = -0.03, t(165) = -.27, p = .78. This latter result indicated that high ISE worked as a buffer, protecting participants from overachievement beliefs.

Figure 1 shows a graphical evaluation of the interaction. It indicates that participants with high fragile self-esteem (high ESE, low ISE) reported the highest levels of overachievement. Participants with low damaged self-esteem (low ESE, high ISE), on the other hand, reported levels of overachievement beliefs that were not the highest in overall terms, but significantly higher when compared with those of participants with consistent low self-esteem, β = 0.29, t(165) = 2.44, p = .02.

3.3 Discussion

The results of our first study showed, with a sample of adolescents, significant relations between self-esteem and general reports of self-defensive strategies. More specifically, zero-order correlations showed that subjective overachievement was positively associated with ESE. This positive correlation might seem counterintuitive, but the investigation of the interaction between ISE and ESE showed that, as hypothesized, it was those participants with fragile self-esteem who reported the highest use of such strategy, and participants with damaged low self-esteem reported scores that were significantly higher as compared to those of participants with consistent low self-esteem.

Interestingly, our analysis indicated the presence of two distinct dimensions in the concern with performance subscale. Besides the expected component, which encompassed the items referring to the necessity to avoid failure, another one emerged which referred to success avoidance. These two components were not correlated negatively, as one would expect if these were opposite aspects of the same dimension. Also, their patterns of relations with self-doubt and self-esteem differed. We interpreted the unexpected component as indicating psychological disengagement. This is a defensive strategy that has been primarily investigated in intergroup relations. It has been convincingly shown that membership in a stigmatized group that is stereotypically associated with bad performance in a given domain (i.e., stereotype threat; Schmader et al., 2001) may lead to devaluation of the domain or discounting of the negative feedback (Tougas et al., 2008). In this way, self-esteem is not negatively affected by a failure in that domain (Schmader et al., 2001). However, performance and intrinsic motivation are negatively impacted. Opposite to overachievers, disengagers withdraw their effort (Osborne, 1997; Osborne & Rausch, 2001). If overachievers jeopardize their possibility to claim their abilities because their successes can be attributed to the exceptional effort, disengagers, on the other hand, undermine their possibility of success in the domain from which they have disengaged. In particular, academic disengagement is associated with befriending delinquent peers and school dropouts (Archambault et al., 2009; Morrison et al., 2002), and psychological disengagement was shown to be negatively associated with global self-esteem during adolescence (Martinot et al., 2020).

The absence of a significant relationship between the psychological disengagement score and ESE (either direct or in interaction with ISE) might suggest that, for those using this defensive strategy, a clear separation exists between the disengaged domains and the sense of self-worth. Psychological disengagement might be a long-term reaction to domains that were initially perceived as threatening and perhaps were originally faced with other strategies, a withdrawal of effort and devaluation of success in such areas. However, a significant negative regression coefficient linked ISE and disengagement in the first step of the regression analysis. This might suggest that a high ISE might protect against this coping strategy. Given that this relation did not emerge in the zero-order correlation analysis and was low in size, we refrain from discussing it further, leaving a better comprehension of this phenomenon to future research.

In Study 1, participants characterized by discrepant self-esteem showed an increased tendency to avoid future bad performances through overachievement. With Study 2, we investigated a different condition in which the relevant performance is situated in the past, so the individual cannot change the outcome of their effort. We will investigate whether participants with discrepant self-esteem will show a greater tendency to use retroactive excuses to avoid the potential implications of a failure for their abilities.

4 Study 2

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Participants

The study was conducted at a Romanian University. Participants were University students recruited using their institutional e-mail lists and received course credits for their voluntary participation. Most participants (i.e., 58.06%) were 2nd year students in Psychology, and other specialities included Computer Sciences, Economics, and Humanities. Out of the 124 participants enrolled in the study, 101 students (55.88% female, mean age 22.86 years, SD = 4.24) did not find the solution to the problem-solving task and were included in the analyses. We did not analyze the data from participants who solved the task, as the present research is focalized on reactions to failure, and their number was too low to allow any meaningful statistical analysis. A sensitivity analysis based on N = 101, conducted with G*Power, with significance level α = 0.05, power (1-β) = 0.80, based on the F-test family for multiple regression with three predictors indicated that we had an adequate level of power for an effect size of f2 = 0.11, which is considered small-to-medium (Cohen, 1992).

4.1.2 Measures

Explicit and Implicit Self-Esteem. Participants answered paper-and-pencil versions of the RSES and the NLT. Regarding the RSES, we used an existing translation that showed good reliability in previous studies on Romanian samples (e.g., Maroiu et al., 2016; Moza et al., 2019). Regarding the NLT, we presented the participants with a list of the letters sorted alphabetically, and they had to rate each letter using a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (I do not like it at all) to 7 (I like it very much). Similar to Study 1, we used the I-algorithm (LeBel & Gawronski, 2009) to compute the scores of the NLT.Footnote 2

Retroactive excuses. We used a short self-report scale developed for this study and containing various self-serving explanations (excuses) that respondents could give, retrospectively, to distance themself from the negative performance in the task so as to diminish the possible implications of this negative performance for one’s abilities. Using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), participants rated items that assessed their tendency to attribute their result to situational factors (sample item: “I did not rest well last night, which has influenced my performance in the previous task”), to environmental disturbances (sample item: “The noise around me constantly distracted my attention so that I could not pay attention to the task I had to fulfill”), to their general inability to perform such tasks (sample item “I think you need special skills to solve problems like the previous one”), or simply allowed participants to minimize the importance of their failure (sample item: “A single task is not enough to assess my potential”). The whole list of items is presented in Table 3. Because this task was specifically developed for this study, we will briefly discuss its psychometric properties in the first part of the Results section.

4.1.3 Procedure

After completing an informed consent form, all participants responded to paper-and-pencil versions of the self-esteem measures (i.e., the RSES and the NLT). Then, we invited each participant to a private space, where we presented the problem-solving task. The instructions for the problem-solving task were: “You have six matchsticks. Your task is to use them to form a figure containing 8 equilateral triangles. You are not allowed to break the matchsticks or to use other materials. You have 4 min to complete the task.” Each participant completed the task alone, and the experimenter returned after 4 min. Most participants (101 out of 124) did not solve the task, and the experimenter presented them with the solution (i.e., to form two overlapping triangles that will form the structure of the star of David). Then, participants completed the Attribution Biases scale.

4.1.4 Hypothesis

We expected that higher self-esteem discrepancies would be related to higher use of retrospective excuses.

4.1.5 Data analysis

For the data analysis, we used the same approach as in Study 1.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Preliminary analyses

In our preliminary analyses, we investigated the internal validity of our criterion variables. We conducted a PCA that, based on parallel analysis and scree plot analysis, indicated that a single factor solution is optimal. Although the internal consistency of the scale containing all 16 items was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = 0.80), we excluded four items with loadings below 0.30 and re-analyzed the data. The remaining 12 items also grouped in a single-factor solution, and the internal consistency of this factor was good (Cronbach’s α = 0.86). Table 3 presents the loadings of all items. We computed Attributional Bias as the summed score of the responses to items in the final solution, and higher values indicate a higher tendency to external attributions of the failure.

4.2.2 Moderation analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations between study variables are presented in Table 4. Regarding the moderation analyses, we followed the analytical approach used in Study 1. Results presented in Table 5 suggested that the post-task attributional bias is associated with low ESE, r (99) = -.35, p < .01, while the regression analysis yielded a significant effect of the interaction between the two forms of self-esteem (β = -0.26, t(98) = -2.17, p = .03). To explain the interaction effect, we conducted a simple slopes analysis. We estimated the relationship between ESE and the attributional bias for high and low levels of ISE (1 SD above and 1 SD below the mean). The simple slope analysis indicated that the relationship between ESE and attributional bias was statistically significant only when ISE was high (β = -0.58, t(97) = -4.14, p < .01) or medium (β = -0.32, t(97) = 3.56, p < .01), not when ISE was low (β = -0.06, t(97) = 0.35, p = .73). The graphical analysis of the interaction, reported in Fig. 2, indicated that also in this case, similar to the pattern that emerged for subjective overachievement in Study 1, it was participants with discrepant self-esteem who made the highest use of retroactive excuses. Participants with low damaged self-esteem (low ESE, high ISE) showed the highest use of retrospective excuses. Participants with fragile self-esteem showed an average use of retrospective excuses that was higher as compared to those with secure high self-esteem, albeit the difference between participants with fragile high self-esteem and secure high self-esteem was not significant, β =-0.29, t(97) = 1.94, p = .06.

4.3 Discussion

Study 2 investigated self-defensive attributional biases after a specific situational failure was experienced; the results confirmed an association between self-esteem and defensive mechanisms: We found evidence that individuals with lower ESE showed more intense use of retroactive excuses as a form of self-serving bias. Notably, this relation between ESE and retroactive excuses differed depending on the level of ISE. Differently from Study 1, in this case, participants with damaged self-esteem used retrospective excuses to the highest intensity.

5 General discussion

This research examined, with two samples of students, two defensive reactions to failure that can be particularly harmful to young people because of their potentially detrimental effect on the development of solid self-knowledge and confidence in one’s abilities (Becht et al., 2021): subjective overachievement and the use of retroactive excuses as a self-serving bias in causal attributions of failure. Addressing the unexplored question of the relation between these defensive mechanisms and discrepant self-esteem helped shed light on the interindividual difference correlates of the use of these strategies.

The present results are consistent with the literature showing the role of self-esteem in reactions to failure and negative outcomes (e.g., Beekman and colleagues, 2017; Tobia et al., 2017), and in particular to the empirical evidence showing a relation between self-esteem inconsistencies and enhanced use of defensive strategies (e.g., Borton et al., 2012; Zeigler-Hill et al., 2011a, 2011b). The results showed that the use of both strategies was related to ESE and the interplay between ESE and ISE, but the patterns of results were different. As concerns the simple associations, subjective overachievement beliefs were positively associated with ESE (Study 1), while the use of retroactive excuses had a negative relation with ESE (Study 2). This may suggest that, depending on the personal beliefs that youngsters hold regarding their value at the explicit level, they tend to face the risk of failure differently. Youngsters with high ESE might be more inclined to face it proactively, working hard to succeed and preserve their high belief in their value. Youngsters characterized by low ESE seem more inclined to a reactive approach: Perhaps because of their lower expectations, they do not put an excessive amount of effort into the task, but, on the other hand, when a failure occurs, they strive to avoid that it damages their self-view and the way others evaluate them.

The interaction between ISE and ESE, evidenced in both studies, provides additional important nuances to the picture. Indeed, in Study 1, we found that the association between subjective overachievement and ESE was significant for participants characterized by low or medium ISE scores. In contrast, it was non-significant and negligible for participants with high ISE scores. The highest scores in subjective overachievement beliefs were observed in participants with fragile self-esteem. This result suggests that a high ISE is protective against this defensive strategy. This finding is consistent with the notion that individuals with secure high self-esteem do not need defenses in front of the risk of negative self-relevant information (Kernis, 2003). In contrast, people with fragile self-esteem, because of the insecurities caused by their lower ISE, are thought to question their positive attitude toward themselves and need frequent validation (Zeigler-Hill & Jordan, 2010).

In Study 2, the interaction showed that the negative association between ESE and the use of retroactive excuses was present for participants with medium and high ISE, but not for those with low ISE. Therefore, this defensive mechanism was accentuated in case of damaged self-esteem. This pattern of results is consistent with the suggestion that individuals with damaged self-esteem may hold what has been called “a glimmer of hope” (Spencer et al., 2005): Even if their reflective evaluations of themselves are less positive than average, their more positive spontaneous affective reactions may stimulate them to strive to restore their damaged self-esteem.

Overall, these results indicate that the interplay between ISE and ESE is related to defensive strategies against failure and further suggest that youngsters use different strategies against failure depending on different patterns of inconsistency. Indeed, individuals might use both strategies to preserve their sense of self-worth, and they intervene in different moments because subjective overachievement is an anticipatory strategy to avoid failure, whereas the use of retroactive excuses acts to limit the damage caused by the failure’s implications for one’s abilities. However, they are importantly different in the context in which they emerge: before or after the task. Subjective overachievement leaves room for the possibility of having success (and, in fact, can increase the possibility of good performance). For subjective overachievement, the individual must believe that a good performance is within their reach, albeit there is uncertainty in how much of an effort is required: Hence the profusion of an enormous effort to avoid results that could cast doubt on a sense of self that, at an explicit and conscious level, is positive but precarious. Retrospective excuses, on the other hand, might express the “glimmer of hope” (Spencer et al., 2005) held by individuals with damaged self-esteem: an attempt to restore a spontaneous positive view of themselves, refusing the implications of a failure that is in line with explicit beliefs, but not with the spontaneous reactions. Future studies should systematically investigate the stability of these different patterns of relations between self-esteem inconsistencies and defensive strategies.

5.1 Limits and directions for future research

Every research has limitations, and this is no exception. Firstly, this is cross-sectional research, and we cannot infer the presence of causal relations between the self-esteem discrepancies and the use of defensive strategies. It is plausible that self-esteem and defensive strategies have reciprocal influences: On the one hand, certain configurations of self-esteem might increase the probability that individuals resort to certain defensive strategies. This is the case when damaged self-esteem needs to be restored, or fragile self-esteem needs to be protected. On the other hand, using these strategies places a veil between oneself and an honest reflection on one's abilities and characteristics, which contributes to maintaining the misalignment between the two self-evaluation dimensions. Experimental research, in which the levels of self-esteem are temporarily manipulated, and longitudinal research following the individuals over time, would be essential to gain an improved understanding of the relationships between self-esteem and defensive mechanisms.

Furthermore, when comparing the results of Study 1 and Study 2, it is important to consider their differences, most notably the age of the participants (adolescents in Study 1 and emerging adults in Study 2). It is possible that, similar to other defensive mechanisms, subjective overachievement and the use of retrospective excuses undergo developmental changes (Cramer, 2015), and their patterns of associations with self-esteem changes in life. For this reason, systematic research might analyze the patterns of use of these strategies at different ages, as well as how their link with self-esteem develops over time; the generalizability of these results to other age groups is an open question for systematic research.

Another limitation for generalizability is that both studies focused on students (high school students in Study 1, university students in Study 2). Students’ populations might be more susceptible to success and failure because they are required to sustain exams and tests more often than non-students and the outcomes of these tests are often taken into great consideration by teachers and parents. Therefore, another important future direction might be investigating whether these results generalize to non-student samples.

Another aspect of the present results worth further investigation concerns the relationship between subjective overachievement and psychological disengagement. In Study 1, these two dimensions emerged from the Concern with Performance subscale of the Subjective Overachievement Scale (Oleson et al., 2000). Subjective overachievement and psychological disengagement have opposite consequences on behavior. The first causes a disproportionate increase in effort to avoid failure at any cost. The second, on the contrary, causes disinterest in success in a specific area and withdrawal of effort. We found that these two dimensions were not negatively correlated, as one would expect if they expressed opposite reactions. This result suggests that some students could respond to the pressures related to the requests they face using both strategies. For example, a student could put a lot of effort into studying, so as not to risk getting bad grades and disappointing the parents. Still, at the same time, s/he might prepare mentally for the possibility of failure by saying themself that: “All in all, I don’t care about getting good grades. I just do it to make my parents happy”. Such a high effort and decrease in intrinsic motivation might be related to higher levels of exhaustion and academic burnout (e.g., Chang et al., 2015; Lyndon et al., 2017) and thus deserves further investigation. Future research should also investigate if, for students with a high tendency to both overachievement and disengagement, the use of these strategies is domain-specific. It is important to understand whether they devote all their efforts to certain domains and withdraw them from others, and how much these defensive reactions are subject—for a given domain—to the specific contingencies of success or failure. Anecdotal evidence from the daily experiences of many educators and parents suggests that some students increase their commitment after they receive good marks, while they react by showing disinterest in the subject after poor results, which could suggest that they make use of both strategies, depending on the immediate feedback.

5.2 Conclusions

Subjective overachievement and retrospective excuses may hinder the important developmental task of identity formation that characterizes adolescence and emerging adulthood. With this research, we highlight two correlates of these defensive strategies, namely ESE and self-esteem inconsistency. The results of this research show, in particular, that individuals with fragile self-esteem may be particularly vulnerable to subjective overachievement and individuals with damaged self-esteem to retrospective excuses. This knowledge can be helpful in identifying better students with such patterns of self-esteem and defensive mechanisms.

Parents and teachers rarely worry when a student shows a high commitment to studying and having good results unless this high commitment is related to stress and discomfort. But high commitment can sometimes conceal subjective overachievement: We need to correctly recognize such cases to avoid the risk of praising and rewarding a strategy that hinders identity development and the formation of consistent self-esteem. Similarly, when a student uses retroactive excuses for their bad results, it is essential to understand whether this signals an attempt to defend one’s damaged self-esteem. The relation between the excessive use of retroactive excuses and self-esteem is important also because it suggests that, if the excuses are an expression of damaged self-esteem, most probably interventions that address only the excuses might be ineffective and it might be more appropriate to help the individual develop more appropriate strategies to cope with negative results.

It is important that scientific research singles out the correlates of such strategies to help teachers and practitioners better understand the meanings of students’ commitment levels and use of excuses, and in particular, whether this commitment and these excuses are defensive strategies. The association between these strategies and self-esteem further suggests that, when dealing with students characterized by a pattern of subjective overachievement or retroactive excuses, it is important to help them distinguish the performance from stable characteristics, and undo the belief that a person having a bad performance is a failure.

One possibility consists in helping students develop incremental implicit beliefs about their abilities. Dweck and her colleagues (e.g., Ehrlinger et al., 2016) have evidenced that some individuals have incremental beliefs about abilities (i.e., they believe that abilities are malleable). In contrast, others have entity beliefs (i.e., they believe that abilities are fixed and stable). Students with incremental beliefs handle negative feedback more constructively, whereas those with entity beliefs tend to avoid challenges and act defensively. Furthermore, experimental research provided causal evidence that the manipulation of incremental beliefs about one’s abilities in individuals characterized by self-doubt positively affected their performance, motivation and other psychological aspects (Zhao et al., 2019). Other approaches, which have proven useful for reducing self-doubt, might help tackle these conditions of increased defensiveness, in particular Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and mindfulness (Wichman & Hermann, 2010).

Availability of data and materials

The data are openly available at this link: https://osf.io/vmtc6/?view_only=9fd67a66b8aa457784eaf55b7cdf1a3a.

Notes

We implemented a Bonferroni criterion because the Principal Component Analysis revealed the presence of two separate sub-dimensions in the Concern with Performance scale. Therefore, we investigated the correlation between the two measures of self-esteem and two different indices of defensive mechanisms.

In this study we asked participants to report both initials, of name and surname, and used both for the computation of the ISE score.

References

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Fallu, J. B., & Pagani, L. S. (2009). Student engagement and its relationship with early high school dropout. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 651–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.007

Arnett, J. J. (2014). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Baggio, S., Studer, J., Iglesias, K., Daeppen, J.-B., & Gmel, G. (2017). Emerging adulthood: A time of changes in psychosocial well-being. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 40(4), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278716663602

Beaton, A. M., Tougas, F., Rinfret, N., & Monger, T. (2015). The psychological disengagement model among women in science, engineering, and technology. British Journal of Social Psychology, 54(3), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12092

Becht, A. I., Nelemans, S. A., Branje, S. J., Vollebergh, W. A., & Meeus, W. H. (2021). Daily identity dynamics in adolescence shaping identity in emerging adulthood: An 11-year longitudinal study on continuity in development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(8), 1616–1633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01370-3

Beekman, J. B., Stock, M. L., & Howe, G. W. (2017). Stomaching rejection: Self-compassion and self-esteem moderate the impact of daily social rejection on restrictive eating behaviors among college women. Psychology & Health, 32(11), 1348–1370. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1324972

Borton, J. L., Crimmins, A. E., Ashby, R. S., & Ruddiman, J. F. (2012). How do individuals with fragile high self-esteem cope with intrusive thoughts following ego threat? Self and Identity, 11(1), 16–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2010.500935

Bosson, J. K., Brown, R. P., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Swann, W. B. (2003). Self-Enhancement Tendencies among people with high explicit self-esteem: The moderating role of Implicit self-esteem. Self and Identity, 2(3), 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309029

Branje, S. (2022). Adolescent identity development in context. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.11.006

Braslow, M. D., Guerrettaz, J., Arkin, R. M., & Oleson, K. C. (2012). Self-doubt. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(6), 470–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00441.x

Campbell, W. K., & Sedikides, C. (1999). Self-threat magnifies the self-serving bias: A meta-analytic integration. Review of General Psychology, 3(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.3.1.23

Carraro, L., Zogmaister, C., Arcuri, L., Pastore, M., & Corti, C. (2013). On the factorial structure of self-esteem as measured by the Italian translation of the self-liking/self-competence scale-revised (SLCS-R). Psicologia Sociale, 8(3), 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1482/74880

Casad, B. J., Petzel, Z. W., & Ingalls, E. A. (2019). A model of threatening academic environments predicts women STEM majors’ self-esteem and engagement in STEM. Sex Roles, 80, 469–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0942-4

Chang, E., Lee, A., Byeon, E., & Lee, S. M. (2015). Role of motivation in the relation between perfectionism and academic burnout in Korean students. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.027

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Cramer, P. (2015). Defense mechanisms: 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Personality Assessment, 97(2), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2014.947997

Crocker, J., & Wolfe, C. T. (2001). Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review, 108(3), 593–623. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.3.593

Duru, E., & Balkis, M. (2014). The roles of academic procrastination tendency on the relationships among self-doubt, self-esteem and academic achievement. Egitim Ve Bilim, 39(173), 274–287.

Ehrlinger, J., Mitchum, A. L., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Understanding overconfidence: Theories of intelligence, preferential attention, and distorted self-assessment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 63(2), 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.11.001

Erol, R. Y., & Orth, U. (2011). Self-esteem development from age 14 to 30 years: A longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(3), 607–619. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024299

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Greenwald, A. G., & Farnham, S. D. (2000). Using the implicit association test to measure self-esteem and self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 1022–1038. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.I022

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

Jordan, C. H., Spencer, S. J., Zanna, M. P., Hoshino-Browne, E., & Correll, J. (2003). Secure and defensive high self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 969–978. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.969

Kernis, M. H. (2000). Substitute needs and the distinction between fragile and secure high self-esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 298–300.

Kernis, M. H. (2003). Toward a conceptualization of optimal self-esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 14(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1401_01

Kernis, M. H., Abend, T. A., Goldman, B. M., Shrira, I., Paradise, A. N., & Hampton, C. (2005). Self-serving responses arising from discrepancies between explicit and implicit self-esteem. Self and Identity, 4(4), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860500146028

Kernis, M. H., Lakey, C. E., & Heppner, W. L. (2008). Secure versus fragile high self-esteem as a predictor of verbal defensiveness: Converging findings across three different markers. Journal of Personality, 76(3), 477–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00493.x

Klassen, R. M., Ang, R. P., Chong, W. H., Krawchuk, L. L., Huan, V. S., Wong, I. Y., & Yeo, L. S. (2009). A cross-cultural study of adolescent procrastination. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19(4), 799–811. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00620.x

Lane, J., Lane, A. M., & Kyprianou, A. (2004). Self-efficacy, self-esteem and their impact on academic performance. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 32(3), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2004.32.3.247

LeBel, E. P., & Gawronski, B. (2009). How to find what’s in a name: Scrutinizing the optimality of five scoring algorithms for the name-letter task. European Journal of Personality, 23(2), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.705

Lobel, T. E., & Teiber, A. (1994). Effects of self-esteem and need for approval on affective and cognitive reactions: Defensive and true self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 16(2), 315–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)90168-6

Loose, F., Régner, I., Morin, A. J., & Dumas, F. (2012). Are academic discounting and devaluing double-edged swords? Their relations to global self-esteem, achievement goals, and performance among stigmatized students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 713–725. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027799

Lyndon, M. P., Henning, M. A., Alyami, H., Krishna, S., Zeng, I., Yu, T. C., & Hill, A. G. (2017). Burnout, quality of life, motivation, and academic achievement among medical students: A person-oriented approach. Perspectives on Medical Education, 6(2), 108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-017-0340-6

Major, B., & Schmader, T. (1998). Coping with stigma through psychological disengagement. In J. K. Swim & C. Stangor (Eds.), Prejudice: The target’s perspective (pp. 219–241). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-012679130-3/50045-4

Maltese, A., Alesi, M., & Alù, A. G. M. (2012). Self-esteem, defensive strategies and social intelligence in the adolescence. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 2054–2060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.164

Maroiu, C., Maricuțoiu, L. P., & Sava, F. A. (2016). Explicit self-esteem and contingencies of self-worth: The moderating role of implicit self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.022

Maree, J. G., & Twigge, A. (2016). Career and self-construction of emerging adults: The value of life designing. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(6), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02041

Martinot, D., Beaton, A., Tougas, F., et al. (2020). Links between psychological disengagement from school and different forms of self-esteem in the crucial period of early and mid-adolescence. Social Psychology of Education, 23(6), 1539–1564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09592-w

McCarty, C. A., Mason, W. A., Kosterman, R., Hawkins, J. D., Lengua, L. J., & McCauley, E. (2008). Adolescent school failure predicts later depression among girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43(2), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.023

McFarlin, D. B., & Blascovich, J. (1981). Effects of self-esteem and performance feedback on future affective preferences and cognitive expectations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(3), 521. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.40.3.521

Mezulis, A. H., Abramson, L. Y., Hyde, J. S., & Hankin, B. L. (2004). Is there a universal positivity bias in attributions? A meta-analytic review of individual, developmental, and cultural differences in the self-serving attributional bias. Psychological Bulletin, 130(5), 711–747. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.711

Midgley, C., Arunkumar, R., & Urdan, T. C. (1996). “If I don’t do well tomorrow, there’s a reason”: Predictors of adolescents’ use of academic self-handicapping strategies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 423–434. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.88.3.423

Morrison, G. M., Robertson, L., Laurie, B., & Kelly, J. (2002). Protective factors related to antisocial behavior trajectories. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 258, 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10022

Moza, D., Maricuțoiu, L., & Gavreliuc, A. (2019). Cross-lagged relationships between self-esteem, self-construal, and happiness in a three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Individual Differences, 40(3), 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000290

Nunnally, J. C. (1967). Psychometric Theory. McGraw-Hill.

Nummenmaa, L., & Niemi, P. (2004). Inducing affective states with success-failure manipulations: A meta-analysis. Emotion, 4(2), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.4.2.207

Olenik-Shemesh, D., Heiman, T., & Keshet, N. S. (2018). The role of career aspiration, self-esteem, body esteem, and gender in predicting sense of well-being among emerging adults. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 179(6), 343–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2018.1526163

Oleson, K. C., Poehlmann, K. M., Yost, J. H., Lynch, M. E., & Arkin, R. M. (2000). Subjective overachievement: Individual differences in self-doubt and concern with performance. Journal of Personality, 68(3), 491–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00104

Osborne, J. W. (1997). Race and academic disidentification. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(4), 728–735. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.4.728

Osborne, J. W., & Rausch, J. L. (2001). Identification with Academics and Academic Outcomes in Secondary Students. [Paper presentation] American Education Research Association Annual meeting, Seattle, WA, United States. Retrieved 21 February, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jason_Osborne2/publication/234565060_Identification_with_Academics_and_Academic_Outcomes_in_Secondary_Students/links/57cd83fc08ae83b37460d76b/Identification-with-Academics-and-Academic-Outcomes-in-Secondary-Students.pdf

Porfeli, E. J., & Lee, B. (2012). Career development during childhood and adolescence. New Directions for Youth Development, 2012(134), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20011

Prezza, M., Trombaccia, F. R., & Armento, L. (1997). La scala dell’autostima di Rosenberg: Traduzione e validazione Italiana [The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Italian translation and validation]. Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali, 233, 35–44.

Reimann, C., Filzmoser, P., Garrett, R., & Dutter, R. (2011). Statistical data analysis explained: Applied environmental statistics with R. Wiley.

Robins, R. W., & Beer, J. S. (2001). Positive illusions about the self: Short-term benefits and long-term costs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(2), 340. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.340

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

Sandstrom, M. J., & Jordan, R. (2008). Defensive self-esteem and aggression in childhood. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(2), 506–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.07.008

Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(3), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

Schmader, T., Major, B., & Gramzow, R. H. (2001). Coping with ethnic stereotypes in the academic domain: Perceived injustice and psychological disengagement. Journal of Social Issues, 57(1), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00203

Schreiber, F., Bohn, C., Aderka, I. M., Stangier, U., & Steil, R. (2012). Discrepancies between implicit and explicit self-esteem among adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43(4), 1074–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.05.003

Schröder-Abé, M., Rudolph, A., & Schütz, A. (2007a). High implicit self-esteem is not necessarily advantageous: Discrepancies between explicit and implicit self-esteem and their relationship with anger expression and psychological health. European Journal of Personality, 21(3), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.626

Schröder-Abé, M., Rudolph, A., Wiesner, A., & Schütz, A. (2007b). Self-esteem discrepancies and defensive reactions to social feedback. International Journal of Psychology, 42(3), 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590601068134

Schunk, D. H., & Meece, J. L. (2006). Self-efficacy development in adolescence. In F. Pajares & T. C. Urdan (Eds.). Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 71–96). Information Age Publishing.

Schutz, A. (1998). Autobiographical narratives of good and bad deeds: Defensive and favorable self-description moderated by trait self-esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology., 17(4), 466–475. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1998.17.4.466

Schwartz, S. J., Forthun, L. F., Ravert, R. D., Zamboanga, B. L., Rodriguez, L., Umana-Taylor, A. J., Filton, B. J., Kim, S. Y., Rodriguez, L., Weisskirch, R. S., Vernon, M., Shneyderman, Y., Williams, M. K., Agocha, V. B., & Hudson, M. (2010). Identity consolidation against health risk behaviors in college-attending emerging adults. American Journal of Health Behavior, 34(2), 214–224. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.34.2.9

Sedikides, C., & Gregg, A. P. (2008). Self-enhancement: Food for thought. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(2), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00068.x

Seery, M. D., Blascovich, J., Weisbuch, M., & Vick, S. B. (2004). The relationship between self-esteem level, self-esteem stability, and cardiovascular reactions to performance feedback. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(1), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.1.133

Selker, R. (2017). medmod: Simple mediation and moderation analysis. R package version 1.0.0. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/medmod/medmod.pdf

Sirriyeh, R., Lawton, R., Gardner, P., & Armitage, G. (2010). Coping with medical error: A systematic review of papers to assess the effects of involvement in medical errors on healthcare professionals’ psychological well-being. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 19, e43. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2009.035253

Spencer, S. J., Jordan, C. H., Logel, C. E., & Zanna, M. P. (2005). Nagging doubts and a glimmer of hope: The role of implicit self-esteem in self-image maintenance. In: A. Tesser, J. V. Wood, D. A. Stapel DA (Eds.). On building, defending and regulating the self: A psychological perspective (pp. 153–170). Psychology Press.

The jamovi project (2021). jamovi (Version 1.6) [Computer Software]. Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org

Tobia, V., Riva, P., & Caprin, C. (2017). Who are the children most vulnerable to social exclusion? The moderating role of self-esteem, popularity, and nonverbal intelligence on cognitive performance following social exclusion. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 789–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0191-3

Tougas, F., Lagace, M., Laplante, J., & Bellehumeur, C. (2008). Shielding self-esteem through the adoption of psychological disengagement mechanisms: The good and the bad news. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 67(2), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.67.2.b

van Tuijl, L. A., de Jong, P. J., Sportel, B. E., de Hullu, E., & Nauta, M. H. (2014). Implicit and explicit self-esteem and their reciprocal relationship with symptoms of depression and social anxiety: A longitudinal study in adolescents. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 45(1), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.09.007

Wichman, A. L., & Hermann, A. D. (2010). Deconstructing the link between self-doubt and self-worth: Ideas to reduce maladaptive coping. In R. M. Arkin, K. C. Oleson, & P. J. Carroll (Eds.), Handbook of the uncertain self (pp. 321–337). Psychology Press.

Yu, J., & McLellan, R. (2019). Beyond academic achievement goals: The importance of social achievement goals in explaining gender differences in self-handicapping. Learning and Individual Differences, 69, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.11.010