Abstract

A large body of experimental research on stereotype threat concentrated on immediate consequences of this effect. Far less attention has been given to the underlying mechanisms that may explain accumulative and long-term consequences of stereotype threat. To shed new light on the dynamic of stereotype threat, the current research examined the strength of associations between experience of stereotype threat, working memory, mathematical achievement and intellectual helplessness using structural equation modeling on representative sample in three age cohorts (13–16 years). Corroborating previous research, working memory was a significant and stable mediator of the relation between chronic stereotype threat and achievement across cohorts. Moving beyond past work, the results showed that mediation through intellectual helplessness was stronger in older cohorts, offering preliminary support to the hypothesis about an accumulative effect of chronic stereotype threat on mathematical achievement. Results are discussed in terms of motivational models of stereotype threat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction and literature overview

Stereotype threat research proved that activating negative stereotypes about intellectual abilities in testing situations can decrease task performance exhibited by minority group members (Steele and Aronson 1995). In their seminal work, Steele and Aronson showed that Afro-Americans who were instructed that a test was diagnostic of their verbal abilities solved fewer verbal items of Graduate Record Examination than Afro-American students in the control condition in which the test was described as non-diagnostic for verbal abilities. Effects of stereotype threat have been documented in a wide range of domains: mathematics (Spencer et al. 1999), intelligence (Croizet et al. 2004), spatial orientation (Tarampi et al. 2016), free recall from memory (Hess et al. 2003), especially when tasks were difficult (Spencer et al. 1999) or required using new strategies (Carr and Steele 2009).

Explanations of observed test performance deficits are based on the assumption that stereotype threat manipulation leads to working memory deficits which are responsible for achievement impairments. For example, Schmader and Johns (2003) documented that negative stereotype activation reduced working memory capacity, as measured by the operational span task that required simultaneous storage and processing of information units. Similar results were obtained using other measures of working memory and its executive functions, such as antisaccade tasks (Jamieson and Harkins 2007), the Stroop-color naming task (Richeson and Shelton 2003; Hutchison et al. 2013) or a GO/NO-GO task (Mrazek et al. 2011). Additional analyses confirmed the mediational role of working memory capacity in explaining the effect of stereotype threat on math test results in female samples (Schmader and Johns 2003).

1.1 Chronic stereotype threat

Most of research on stereotype threat has traditionally focused on the experimentally induced impact of stereotypes on performance and academic achievement. This influence is temporary, as it is limited to the experimental situation and reversible effects of stereotype threat (see review: Schmader et al. 2008). However, in real educational settings stereotype threat does not appear at a single occasion but it repeats over time. Only recently, however, the consequences of such repeated experiences of stereotype threat have gained on importance (Woodcock et al. 2012; Kalokerinos et al. 2014).

This perspective that looks specifically at the process of motivational and cognitive changes as a consequence of chronic stereotype threat has not been studied extensively. In one of few works on that matter, conducted in the occupational context, von Hippel et al. (2011) indicated that the more strongly women working in male-oriented domains experienced stereotype threat the more negative were their job attitudes. These employees had also lower career aspirations. Similarly, recent research has also revealed that in female workers’ reduced job satisfaction, and elevated burnout symptoms (e.g., emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced personal accomplishment) are significantly predicted by chronic stereotype threat and these relations are mediated by negative emotions (Bedyńska and Żołnierczyk-Zreda 2015).

So far, there is scarcity of research on chronic stereotype threat in educational settings. In one of few studies that have been conducted, Woodcock et al. (2012) evidenced motivational deficits, namely a weaker intention to persist in science and a lower level of scientific identification in Latino students who experienced stereotype threat during their scientific career. This disidentification with scientific domain results from attempts to cope with stereotype threat and it builds on over time leading to final domain abandonment. Although domain disidentification is a well-documented consequence of stereotype threat, little is known about potential mediators of this relationship. We assume that intellectual helplessness may be a potential mediator of chronic stereotype threat and school achievement in stereotyped domain.

1.2 Intellectual helplessness

Intellectual helplessness is theoretically rooted in the informational model of learned helplessness (e.g., Sedek and Kofta 1990; Kofta and Sedek 1998) extended to the educational domain of school learning. This model (Kofta and Sedek 1998; Sedek and Kofta 1990; Sedek et al. 1993; von Hecker and Sedek 1999) strongly contrasts mental activity of people in controllable and uncontrollable task situations. In controllable situations mental activity is systematic and productive so that by paying attention to the requirements of the task and selecting diagnostic pieces of information people quickly notice the progress in task solution. This progress is additionally facilitated by applications of generative modes of thinking such as building mental models or developing plans with sub-goals. However, in uncontrollable task situations (i.e., unsolvable tasks) the mental activity of people is qualitatively different so that despite intensive mental efforts a lack of any progress in problem understanding is observed. Even when an individual might formulate some preliminary hypotheses it would be impossible for her or him to differentiate between good and poor options. According to this theoretical framework long-lasting cognitive exertion without any progress leads to a dysphoric psychological state called “cognitive exhaustion”. The state was found to seriously diminish the generation of new ideas or plans and was especially disruptive in task situations demanding more complex information processing such as initiating nonstandard task solutions or generating mental models (Kofta and Sedek 1998; Sedek and Kofta 1990; von Hecker and Sedek 1999; von Hecker et al. 2013).

The concept of intellectual helplessness (Rydzewska et al. 2017; Sedek and McIntosh 1998) applies the informational model of learned helplessness to difficulties in the acquisition of new and complex school knowledge (e.g., understanding the logarithms on math lessons). It assumes that repeated difficulties in assimilating new material despite the prolonged mental effort constitute a critical condition for the development of intellectual helplessness symptoms in specific school subjects (e.g., motivational loss or negative emotions). Repeated situations of no progress in understanding during class learning produce a state of cognitive exhaustion and in consequence block active thinking (e.g., skills involving comparison, reasoning or building consistent knowledge schemas). As demonstrated by previous research, intellectual helplessness is not only related to cognitive deficits (lower school achievements measured with grades and scores on knowledge tests), but also leads to motivational (lack of intrinsic and instrumental motivation, disengagement from the domain), and emotional (negative emotions, anxiety) dysfunctions in educational settings (Rydzewska et al. 2017; Sedek and McIntosh 1998).

2 Aims of the present study

Chronic stereotype threat is a dynamic process. However, almost no research, to our knowledge, has examined the motivational (intellectual helplessness) and cognitive (working memory) changes evoked by chronic stereotype threat. The present study advances literature on stereotype threat in several substantial ways. The central aim of this study is to deliver a tentative evidence on dynamics of motivational and cognitive changes as an effect of chronic stereotype threat. To do so, we examine the strength of mediational links between chronic stereotype threat and mathematical achievement via intellectual helplessness and working memory in three age cohorts (13-, 14-, and 15-year old) of female students. This model corroborates our previous research (Bedyńska et al. 2018).

Following Woodcock et al.'s (2012) reasoning, we hypothesize that the experience of stereotype threat in educational settings is rather frequent and continually repeating. Therefore, some effects of chronic stereotype threat may be stronger in older cohorts. Borrowing logic from intellectual helplessness studies (e.g., Sedek and McIntosh 1998), we assume that motivational symptoms of intellectual helplessness develop gradually so that the mediational path from chronic stereotype threat and achievement through intellectual helplessness would become stronger in older cohorts. Additionally, the repeated experience of stereotype threat should lead to a switch into cognitive exhaustion, with cognitive resources being blocked. In consequence, the strength of the mediational path from stereotype threat to math achievement via working memory should be similarly strong in all cohorts of female students.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Participants and procedure

Data from six hundred twenty-two females from three levels of classes (three cohorts) in gender mixed secondary schools was analyzed in the study. There were 214 first cohort students (Myears = 13.52, SD = 0.307), 195 second cohort students (Myears = 14.62, SD = 0.519), and 213 third cohort students (Myears = 15.54, SD = 0.312). The sampling procedure with stratification was implemented. In the first step, 24 secondary schools were randomly sampled from two regions of Poland and from three school locations (village, small city, medium city). In the second step, classes were randomly selected from each school. All students belonging to the selected class were invited to the study (655 female students were selected). Around 5% of the invited students were not able to participate in the study due to their absence at school, therefore the final sample consisted of 622 students.

The research protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Educational Research Institute. The present study was conducted in compliance with ethical standards adopted by the American Psychological Association (APA 2010). Accordingly, prior to participation, pupils, parents and school authorities were informed about the general aim of the research, and about the anonymity of student’s data. The research was presented as testing new online educational games and none of the students resigned from the participation during the study. All parents were asked to sign a written consent for their children to participate in the study. The participation was voluntary and pupils did not receive compensation for their participation.

Data was collected during regular school hours in a single session that lasted 45 min. First, the procedure and the aim of the study were explained to students. Then students solved Functional Aspects of Working Memory Test (FAWMT), and then online scales assessing chronic stereotype threat, intellectual helplessness, gender identityFootnote 1 and mathematical achievement among other self-descriptive measures regarding their learning motivation, attitudes toward school and learning. These additional questions were administered before the stereotype threat scale to avoid any potential influence of stereotype threat activation.

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Working memory

Computerized Functional Aspects of Working Memory Test was used to measure working memory. The FAWMT consists of three tasks that measure simultaneous storage and processing function, supervision function, and relational function of working memory. The test was adapted from an experimental procedure used by Oberauer et al. (2000, 2003) and three tasks were selected to provide the functional complexity of the working memory (Kane et al. 2004; Oberauer et al. 2003). The test proved to have a high predictive value of early school mathematical achievement (Krejtz and Sedek 2014; Sedek et al. 2016). The percentage of correct answers constituted the indicator of the tasks.

3.2.2 Intellectual helplessness

We used four items selected from the Intellectual Helplessness Scale (IHS, Sedek and McIntosh 1998) to assess the level of intellectual helplessness. Students provided, on a 6-point Likert type scale (from 1—‘never’ to 6—‘always’), answers to questions concerning their feelings and thoughts during math classes which were symptomatic for intellectual haplessness, e.g.,—‘I feel tired’; ‘I feel helpless’. The short version of the scale showed high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.80), similarly to the IHS.

3.2.3 Chronic stereotype threat

Chronic Stereotype Threat Scale (CSTS) was constructed on the basis of Steele and Aronson’s scale (1995, Experiment 4). Original items were rephrased. We included two items measuring specific stereotype threat of being judged by other students (e.g., ‘Other students in my class feel that I have a lower mathematical ability because of my gender’), one item measuring stereotype threat in relations to the teacher (i.e., ‘I worry that if I fail, my teacher will attribute my poor performance to my gender’), and three items measuring general stereotype threat (e.g., ‘I worry that if I fail during mathematical test, it will prove that all girls are poor at maths’). Participants provided their answers on a 6-point Likert scale, with 1—‘strongly disagree’ and 6—‘strongly agree’. The reliability of the scale was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.89). To test construct validity of the CSTS confirmatory factor analysis was conducted and it supported unidimensionality of the scale [Χ2 = 73.556, df = 14, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.928, TLI = 0.891, SRMR = 0.047, RMSEA = 0.083, 90% CI (0.065, 0.102), p < 0.01].

3.2.4 Mathematical achievement

Mathematical achievement was measured with self-assessed Grade Point Average (GPA) in mathematics from two semesters prior the study. It is important to note that in the Polish educational system a higher GPA reflects better achievement, with 1—‘not passing’, and 6—‘excellent’ grade.

3.3 Data preparation and analytical approach

All analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén 2015). Structural equation modeling with complex sampling and the Maximum Likelihood Robust (MLR) approach was used to deal with clustered data (students nested in classes) and continuous but non-normally distributed variables (Muthén and Satorra 1995).

In the first step of data preparation, five classes smaller than three students were excluded from the analysis (ten participants). Additionally, four students were excluded from the data set due to missing values on at least one of the variables. In the second step, a preliminary model was constructed with multiple mediation with working memory capacity as a latent variable and intellectual helplessness as an observed variable. A multiple mediation with intellectual helplessness and working memory as potential mediators was tested using the INDIRECT function in Mplus. On the basis of the preliminary model we proposed a reduced model in which nonsignificant paths were excluded. The proposed mediational paths of chronic stereotype threat and mathematical achievement through (1) intellectual helplessness and (2) working memory were investigated using 95% confidence intervals (CI) method (MacKinnon et al. 2002). According to this approach, the indirect effect is significant if the CI does not include zero.

All structural models were evaluated using fit indices following Kline’s (2011) recommendations. We used Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) as well as the general fit based on Χ2 test of model fit and its associated probability (p). We used the most widely recommended cut-off values indicative of an adequate model fit to the data, respectively: RMSEA and SRMR < 0.06 and < 0.08, CFI and TLI > 0.95 and > 0.90 (Lance et al. 2006).

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

The relation between variables included in the model and the associated descriptive statistics for three age cohorts are shown in Table 1. Generally, in all three cohorts, mathematical achievement was negatively correlated with intellectual helplessness, and positively correlated with all three functional aspects of working memory. Stereotype threat was also mildly correlated with intellectual helplessness and working memory measures.

4.2 Path model with working memory and intellectual helplessness as mediators

4.2.1 Evaluation of the model

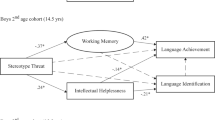

Results indicated that the model with intellectual helplessness and working memory as mediators (see Fig. 1) achieved quite a good fit to the data. The general test of fit for the reduced model was nonsignificant Χ2 = 34.39, df = 26, p = 0.13, and it was supported by the fit indices values: CFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.964, RMSEA = 0.039, 90% CI (0.001, 0.072), p = 0.667. Only SRMR value (0.083) exceeded the acceptable value of good fit. The model explained 26.2% of mathematical achievement variability (R2 = 0.262) in the first cohort, 31.2% (R2 = 0.312) in the second cohort and 39.8% (R2 = 0.398) in the third cohort. Chi square contributions from each group were as follows: 13.22 for the first cohort, 5.95 for the second cohort, and 15.23 for the third cohort. The path coefficients for all three cohorts are displayed in Table 2.

Full mediational models in three age cohorts predicting mathematical achievement by chronic stereotype threat with two mediators: working memory, and intellectual helplessness. Note: non-significant paths are indicated by dashed lines, while significant paths are indicated by solid lines; all coefficients are standardized solutions

4.2.2 Model for the first cohort (13.5 years)

In the first cohort, majority of the relationships between the variables is consistent with the hypotheses. First, stereotype threat was negatively related to working memory (β = − 0.300, p < 0.001) and positively to intellectual helplessness (β = 0.135, p = 0.024). Working memory was a significant predictor of mathematical achievement (β = 0.419, p < 0.001). Intellectual helplessness was negatively associated with mathematical achievement (β = − 0.181, p = 0.012). Second, to analyze the mediational role of working memory and intellectual helplessness, three indirect effects were calculated: (1) stereotype threat on mathematical performance mediated only by helplessness, (2) stereotype threat on mathematical performance mediated only by working memory, (3) stereotype threat on mathematical performance mediated by both mediators: intellectual helplessness and working memory. The analysis of the indirect effects showed that only working memory was a significant mediator of the relation between stereotype threat and mathematical achievement [β = − 0.126, p = 0.003, CI (− 0.191, − 0.041)].

4.2.3 Model for the second cohort (14.6 years)

A similar pattern of the relationships between the variables was obtained for the second cohort. Stereotype threat was negatively related to working memory (β = − 0.380, p < 0.001) and positively to intellectual helplessness (β = 0.281, p < 0.001). Working memory was positively related to mathematical achievement (β = 0.400, p = 0.001), while intellectual helplessness was negatively related to achievement (β = − 0.209, p = 0.009). As in the previous group, three indirect effects were calculated and these analyses suggested that both paths for mediators were significant: indirect effect via working memory was slightly stronger [β = − 0.152, p = 0.039, CI (− 0.256, − 0.004)] than via intellectual helplessness [β = − 0.059, p = 0.038, CI (− 0.097, − 0.003)]. Both mediators operated in parallel and not in sequence because the indirect effect with both variables as mediators was not significant.

4.2.4 Model for the third class level (15.5 years)

Results for the third group of students matched the results of the second cohort. Again, stereotype threat was negatively associated with working memory (β = − 0.317, p < 0.001) and positively with intellectual helplessness (β = 0.194, p = 0.022). Similarly to previous groups, both working memory (β = 0.341, p < 0.001), and intellectual helplessness (β = − 0.380, p < 0.001) were significant predictors of mathematical achievement and both indirect effects via those variables were significant—indirect effect via intellectual helplessness was a bit stronger than in previous groups [β = − 0.074, p = 0.033, CI (− 0.144, − 0.003)] while indirect effect via working memory was at the similar level [β = − 0.108, p = 0.001, CI (− 0.172, − 0.045)].

To sum up, path models showed that working memory was a mediator of the relationship between chronic stereotype threat and mathematical achievement in all age cohorts with a similar effect sizes across groups. As predicted, the mediational effect of intellectual helplessness was stronger in older participants and nonsignificant in younger, supporting the postulated accumulative effect of chronic stereotype threat on motivational consequences of repeated exposure to stereotype threat. Additionally, mediational effects—via working memory and via intellectual helplessness—seemed to be independent as a mediational path involving both mediators in sequence was not significant.

5 Discussion

Bearing in mind the prevalence of stereotype threat in educational settings, understanding the dynamics of this phenomenon is of great importance. The present study was designed to corroborate the role of working memory capacity as a well-established mediator and to test a new mechanism of stereotype threat based on intellectual helplessness. Our findings suggest, similarly to previous research, that working memory capacity plays a mediational role in the relation of chronic stereotype threat and mathematical achievement, mapping the causal mechanism of stereotype threat proposed by Schmader et al. (2008). Additionally, we demonstrated that intellectual helplessness may transmit influence of chronic stereotype threat into mathematical underperformance. In our opinion, the latter result helps to integrate two accounts explaining working memory deficits observed under stereotype threat condition: the integrated model of stereotype threat proposed by Schmader et al. (2008), and the “mere effort” model formulated by Jamieson and Harkins (2007). Schmader and collaborators posit that cognitive deficits in stereotype threat are due to intrusive thoughts and monitoring processes, while Jamieson and Harkins (2007) suggest that working memory deficits are caused by extra motivation not to confirm the stereotype. We posit that these two models can be integrated into a two-stage processual model that follows the stages of the intellectual helplessness model: with cognitive mobilization as the first and cognitive exhaustion as the second stage. The first phase is well explained by the “mere effort” account, while the second one is better modelled by the integrated model of stereotype threat proposed by Schmader et al. (2008).

Empirically, our work contributes to the understanding of the dynamics of chronic stereotype threat by testing the strength of both mediators across three age cohorts. As predicted, the strength of the mediational path based on cognitive factor, that is working memory, was stable across three age cohorts. A different pattern emerged in the motivational mechanism involving intellectual helplessness. In the youngest cohort, there was no significant mediational relationship between stereotype threat and mathematical achievement via intellectual helplessness. This mediational relation involving intellectual helplessness emerged in the second and third age cohort. Such a pattern of results supports the hypothesis predicting the cumulative nature of the motivational mechanism of chronic stereotype threat based on intellectual helplessness. The cumulative nature of negative motivational consequences of intellectual helplessness may explain chronic domain disengagement (Woodcock et al. 2012). To sum up, the analyses yielded clear evidence that two mediators—a decrease in working memory and an increase in learned helplessness level—operate as parallel mechanisms leading to mathematical performance deficits. As predicted, the first effect is stable, while the second has a more accumulative nature and grows over time.

5.1 Limitations to the present research and future directions

It is important to note three limitations of this study. First, only one measure of school achievement, namely self-reported actual Grade Point Average, was measured. Although some educational research showed a strong link between GPA and standardized tests (Skórska et al. 2014; Brown et al. 2015), it can be strongly contaminated by teachers’ expectations and beliefs. To eliminate the influence of this factor, more standardized measures of school achievement such as final or semester tests should be applied in further studies. Second, the cross-sectional research design of the study seems to be another limitation of the study. In order to examine a causal relationship between the variables entered into the path model proposed above, a temporal sequence between variables should be tested in longitudinal studies. Third, the link between stereotype threat and performance may be influenced by several moderators. The literature on stereotype threat offers at least several suggestions, such as identification with the stereotypized domain (Aronson et al. 1999; Keller 2007), identification with one’s groups (Schmader 2002; Tempel and Neumann 2015), stereotype endorsement (Schmader et al. 2004), the level of achievement (Régner et al. 2016), or test anxiety (Tempel and Neumann 2014). In our study we used only one item to measure gender identity. With relatively small sample sizes in three age cohorts the results were equivocal and need to be replicated in the future studies with a more complex assessment of gender identity. Additionally, testing more complex patterns of moderation, involving more than one moderator might shed more light on the nature of stereotype threat. Future research examining the mechanism based on intellectual helplessness should consider addressing abovementioned limitations.

5.2 Conclusions

This research offers an important insight into the dynamics of chronic stereotype threat. It demonstrates intellectual helplessness as a novel mediator by which negative stereotype activation may influence not only performance but also identification with the domain. This mechanism should be highly important for teachers and policymakers as it can shape the interest and further motivation to pursuit education in STEM domains. As a recent analysis of PISA results demonstrated, these personal interests may have a stronger effect on engagement in STEM than equality policy, especially in equally-gender countries (Stoet and Geary 2018).

Notes

Following a reviewer suggestion we tested a model with gender identity as a moderator of relationship between stereotype threat and mathematical achievement but the results were inconclusive, and we decided not to report the results.

References

APA. (2010). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/.

Aronson, J., Lustina, M. J., Good, C., Keough, K., Steele, C. M., & Brown, J. (1999). When white men can’t do math: Necessary and sufficient factors in stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(1), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1998.1371.

Bedyńska, S., Krejtz, I., & Sedek, G. (2018). Chronic stereotype threat is associated with mathematical achievement on representative sample of secondary schoolgirls: The role of gender identification, working memory, and intellectual helplessness. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00428.

Bedyńska, S., & Żołnierczyk-Zreda, D. (2015). Stereotype threat as a determinant of burnout or work engagement. Mediating role of positive and negative emotions. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 21(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2015.1017939.

Brown, J. L., Halpin, G., & Halpin, G. (2015). Relationship between high school mathematical achievement and quantitative GPA. Higher Education Studies, 5(6), 1–8.

Carr, P. B., & Steele, C. M. (2009). Stereotype threat and inflexible perseverance in problem solving. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.003.

Croizet, J., Després, G., Gauzins, M., Huguet, P., Leyens, J., & Méot, A. (2004). Stereotype threat undermines intellectual performance by triggering a disruptive mental load. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(6), 721–731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204263961.

Hess, T. M., Auman, C., Colcombe, S. J., & Rahhal, T. A. (2003). The impact of stereotype threat on age differences in memory performance. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(1), P3–P11. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.1.p3.

Hutchison, K. A., Smith, J. L., & Ferris, A. (2013). Goals can be threatened to extinction using the Stroop task to clarify working memory depletion under stereotype threat. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612440734.

Jamieson, J. P., & Harkins, S. G. (2007). Mere effort and stereotype threat performance effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(4), 544–564. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.544.

Kalokerinos, E. K., von Hippel, C., & Zacher, H. (2014). Is stereotype threat a useful construct for organizational psychology research and practice? Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 7(3), 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/iops.12167.

Kane, M. J., Hambrick, D. Z., Tuholski, S. W., Wilhelm, O., Payne, T. W., & Engle, R. W. (2004). The generality of working memory capacity: A latent variable approach to verbal and visuospatial memory span and reasoning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133, 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.133.2.189.

Keller, J. (2007). Stereotype threat in classroom settings: The interactive effect of domain identification, task difficulty and stereotype threat on female students’ maths performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906x113662.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Kofta, M., & Sedek, G. (1998). Uncontrollability as a source of cognitive exhaustion: Implications for helplessness and depression. In M. Kofta, G. Weary, G. Sedek, M. Kofta, G. Weary, & G. Sedek (Eds.), Personal control in action: Cognitive and motivational mechanisms (pp. 391–418). New York: Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-2901-6_16.

Krejtz, I., & Sedek, G. (2014). Właściwości psychometryczne testu (Psychometric properties of the FAWTM test). In R. Kaczan, P. Rycielski, K. Rzeńca, & K. Sijko (Eds.), Metody diagnozy na pierwszym etapie edukacyjnym (Diagnostic Tools at the Primary Phase of Education) (pp. 217–222). Warszawa: Instytut Badań Edukacyjnych.

Lance, C. E., Butts, M. M., & Michels, L. C. (2006). The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria what did they really say? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 202–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105284919.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4.

Mrazek, M. D., Chin, J. M., Schmader, T., Hartson, K. A., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2011). Threatened to distraction: Mind-wandering as a consequence of stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(6), 1243–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.011.

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Muthén, B. O., & Satorra, A. (1995). Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. In P. V. Marsden (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 267–316). Washington, DC: American Sociological. https://doi.org/10.2307/271070.

Oberauer, K., Süß, H. M., Schulze, R., Wilhelm, O., & Wittmann, W. W. (2000). Working memory capacity facets of a cognitive ability construct. Personality and Individual Differences, 29, 1017–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(99)00251-2.

Oberauer, K., Süß, H. M., Wilhelm, O., & Wittman, W. W. (2003). The multiple faces of working memory: Storage, processing, supervision, and coordination. Intelligence, 31, 167–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-2896(02)00115-0.

Régner, I., Selimbegović, L., Pansu, P., Monteil, J. M., & Huguet, P. (2016). Different sources of threat on math performance for girls and boys: The role of stereotypic and idiosyncratic knowledge. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 637. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00637.

Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2003). When prejudice does not pay effects of interracial contact on executive function. Psychological Science, 14(3), 287–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.03437.

Rydzewska, K., Rusanowska, M., Krejtz, I., & Sedek, G. (2017). Uncontrollability in the classroom: The intellectual helplessness perspective. In M. Bukowski, I. Fritsche, A. Guinote, & M. Kofta (Eds.), Coping with the lack of control in the social world (pp. 62–79). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Schmader, T. (2002). Gender identification moderates stereotype threat effects on women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(2), 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2001.1500.

Schmader, T., & Johns, M. (2003). Converging evidence that stereotype threat reduces working memory capacity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 440–452. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.440.

Schmader, T., Johns, M., & Barquissau, M. (2004). The costs of accepting gender differences: The role of stereotype endorsement in women’s experience in the math domain. Sex Roles, 50(11–12), 835–850. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:sers.0000029101.74557.a0.

Schmader, T., Johns, M., & Forbes, C. (2008). An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychological Review, 115(2), 336–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.115.2.336.

Sedek, G., & Kofta, M. (1990). When cognitive exertion does not yield cognitive gain: Toward an informational explanation of learned helplessness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 729–743. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.729.

Sedek, G., Kofta, M., & Tyszka, T. (1993). Effects of uncontrollability on subsequent decision making: Testing the cognitive exhaustion hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1270–1281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.6.1270.

Sedek, G., Krejtz, I., Rydzewska, K., Kaczan, R., & Rycielski, P. (2016). Three functional aspects of working memory as strong predictors of early school achievements: The review and illustrative evidence. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 47(1), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1515/ppb-2016-0011.

Sedek, G., & McIntosh, D. N. (1998). Intellectual helplessness: Domain specificity, teaching styles, and school achievement. In M. Kofta, G. Weary, & G. Sedek (Eds.), Personal control in action: Cognitive and motivational mechanisms (pp. 391–418). New York: Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-2901-6_17.

Skórska, P., Świst, K., & Szaleniec, H. (2014). Szacowanie trafności predykcyjnej ocen szkolnych z wykorzystaniem hierarchicznego modelowania liniowego. Edukacja, 3(128), 75–94.

Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(1), 4–28. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1998.1373.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797.

Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2018). The gender-equality paradox in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education. Psychological Science, 29(4), 581–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617741719.

Tarampi, M. R., Heydari, N., & Hegarty, M. (2016). A tale of two types of perspective taking sex differences in spatial ability. Psychological Science, 27(11), 1507–1516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616667459.

Tempel, T., & Neumann, R. (2014). Stereotype threat, test anxiety, and mathematics performance. Social Psychology of Education, 17(3), 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9263-9.

Tempel, T., & Neumann, R. (2015). Gender role orientation moderates effects of stereotype activation on test performances. Social Psychology, 47(2), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000259.

von Hecker, U., & Sedek, G. (1999). Uncontrollability, depression, and the construction of mental models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(4), 833–850. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.4.833.

von Hecker, U., Sedek, G., & Brzezicka, A. (2013). Impairments in mental model construction and benefits of defocused attention: Distinctive facets of subclinical depression. European Psychologist, 18(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000133.

von Hippel, C., Issa, M., Ma, R., & Stokes, A. (2011). Stereotype threat: antecedents and consequences for working women. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029825.

Woodcock, A., Hernandez, P. R., Estrada, M., & Schultz, P. (2012). The consequences of chronic stereotype threat: Domain disidentification and abandonment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(4), 635–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029120.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of Piotr Rycielski in data acquisition and management.

Funding

The presented study was a part of the system level project “Quality and effectiveness of education—strengthening institutional research capabilities” executed by the Educational Research Institute and co-financed by the European Social Fund (Human Capital Operational Programme 2007–2013, Priority III High quality of the education system). This work was supported by the National Science Centre, Poland, under Grant 2015/17/B/HS6/04185 awarded to Grzegorz Sedek.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bedyńska, S., Krejtz, I. & Sedek, G. Chronic stereotype threat and mathematical achievement in age cohorts of secondary school girls: mediational role of working memory, and intellectual helplessness. Soc Psychol Educ 22, 321–335 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09478-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09478-6