Abstract

Intergroup conflicts can be triggered and perpetuated by collective perceptions of injustice. In two experiments, we applied the qualifying of subjective justice views, a justice-focused intervention initially introduced to resolve interpersonal conflicts, and evaluated whether it can mitigate intergroup conflicts. This intervention included explicating opposing justice perceptions, explaining the dilemma structure of justice conflicts, and emphasizing that each conflict party applies different justice standards in different situations. In a realistic conflict setting, among advantaged group members, the intervention enhanced the willingness to pay monetary concessions to the out-group. This effect was mediated through an enhanced understanding of the justice dilemma (Study 2) and legitimacy judgments of the out-group’s justice claim (Studies 1 and 2). Furthermore, effects of the justice-focused intervention were compared to those of empathy induction as a benchmark to evaluate the effectiveness. The comparison provided additional evidence for the effectiveness of the justice-focused intervention to mitigate intergroup conflicts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social conflict is a ubiquitous phenomenon in human life. It can offer the potential for personal growth and social enhancement (Rubin et al., 1994), but the escalation of conflict often has detrimental consequences for individuals and collectives involved. Accordingly, devising measures to mitigate conflicts early on is a task of high importance.

While conflict contexts are diverse, most conflicts are characterized by asymmetries with respect to power or resources as well as seemingly incompatible goals or values of the parties involved (Bar-Tal & Halperin, 2011). Such asymmetries and incompatibilities may result in very different understanding of what is just or unjust (Kim & Smith, 1993; Mikula & Wenzel, 2000). As a consequence, (collective) decisions and actions are likely to be in line with the in-group’s justice standards but to simultaneously violate those of an out-group. Conversely, perceived violations of the in-group’s justice standards by an out-group trigger strong negative emotions (e.g., Barclay et al., 2005) and intentions to retaliate (Gollwitzer & Denzler, 2009). As such, opposing perceptions of justice can be at the core of conflict emergence and escalation (see also Törnblom & Kazemi, 2012). Dealing with these perceptions thus seems indispensable when aiming to prevent the escalation of conflicts (Müller et al., 2008). In the present paper, we evaluated an intervention strategy specifically directed at discrepant justice perceptions in an intergroup conflict.

The Necessity of Reconciling Discrepant Justice Views

Discrepancies in justice perceptions may arise when parties apply different justice standards in the same situation. For example, regarding the allocation of resources, need and equity represent alternative justice standards that, applied in the same situation, lead to conflicting solutions as a matter of principle (Deutsch, 1975). One conflict party may assert their own entitlement to a resource because of a special need for this resource, for instance to guarantee survival or to allow adequate performance (neediness claim), whereas for another conflict party, its own contributions or achievements may constitute a legitimate claim for the goods in question (equity claim). According to the conceptualization of justice conflicts by Törnblom and Kazemi (2012), these opposing principles constitute a conceptual distributive justice conflict that can manifest in social conflict between individuals or groups.

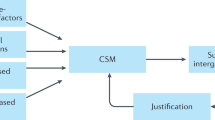

In the context of interpersonal conflicts, Montada (2003, 2007) introduced an intervention strategy specifically aimed at reconciling divergent justice perceptions. This strategy is called qualifying subjective justice views (Montada, 2007) and consists of three central steps. First, subjective justice standards of the conflict parties are identified and explicated. This allows for addressing the core conflict regarding fundamental values underlying claims for resources. Second, the dilemma structure of justice conflicts is explained and discussed on a general level. The goal is to help conflict parties understand that alternative justice standards that are incommensurate as a matter of principle can be applied in one situation (i.e. a justice dilemma). Third, to facilitate this understanding, examples of situations are given in which a single person may apply different and principally conflicting justice standards. Through these steps, the intervention strategy presents diverging justice perceptions as equally legitimate, thereby qualifying subjective justice views.

Since divergent justice views often constitute the core of intergroup conflicts, we argue that qualifying these views should also be effective in mitigating intergroup conflicts. Hence, the goal of the present research was to systematically implement the central steps of qualifying subjective justice views in a justice-focused intervention program at the group level and to test its effectiveness in mitigating conflict. Concretely, we administered the justice-focused intervention to members of an advantaged group that put forward an equity claim and tested whether it would increase their willingness to pay concessions to members of a disadvantaged group that put forward a neediness claim.

Comparing Intervention Techniques

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of the justice-focused intervention, we considered it necessary to situate its effects within the realm of existing interventions. This would allow us to determine how the justice-focused intervention fares in comparison with other interventions, rather than merely testing whether it mitigates conflict in comparison to a situation in which no intervention is applied. To this end, we used a well-established intergroup conflict intervention as a benchmark, namely empathy induction (for an overview, see Batson & Ahmad, 2009). Empathic responses to thoughts and feelings of out-group members have been shown, for example, to improve attitudes towards the out-group and increase the willingness to help the out-group (Batson & Ahmad, 2009; Čehajić-Clancy et al., 2016). In our studies, we compared the justice-focused intervention with empathy induction through perspective-taking, considered to be the cognitive component of empathy (Batson et al., 1997). We argue that by addressing thoughts and feelings of out-group members, it seems plausible that out-group’s justice claims would appear more legitimate as a side effect. In other words, empathy induction might contribute to legitimizing the out-group’s claim, similar to the justice-focused intervention.

However, there are some critical differences between the two interventions: First, per definition, the two interventions should function partly through different mechanisms; while the justice-focused intervention requires the understanding of the dilemma structure on an abstract level, empathy induction should take an emotional route. Second, rather than acknowledging both claims simultaneously (a key component of the justice-focused intervention), empathic responses guide thoughts and feelings towards the suffering and needs of the out-group (Batson et al., 1999). To the degree that the out-group’s claim is then seen as more justified, it becomes more difficult to see one’s own claim as legitimate. Consequently, empathy induction might mitigate conflict through increased legitimacy perceptions of the out-group’s claim and decreased legitimacy perceptions of the in-group’s claim.

In summary, we expected that the justice-focused intervention and empathy induction would lead to the perception of an out-group’s claim as more legitimate, compared to a control condition without intervention (Hypotheses 1a and 1b). Conversely, with regard to the in-group’s claim, we expected that the justice-focused intervention should not affect as how legitimate it is perceived, compared to the control condition (Hypothesis 2a), while empathy induction should decrease its perceived legitimacy (H2b).

For both interventions, we predicted that heightened legitimacy perceptions of the out-group’s claim should help to settle a conflict by increasing the willingness to make concessions to the out-group (Hypotheses 3a and 3b). Here, we also explored whether legitimacy perceptions of the in-group’s claim affect the willingness to make concessions as well.

The Present Research

To test our hypotheses, we conducted two experiments in the context of a realistic conflict concerning the allocation of tuition fees among two university departments. Between 2006 and 2013, some German federal states raised tuition fees for university students. The decision to introduce tuition fees was controversial, and intense conflicts emerged over how this money should be spent (e.g., Friedmann, 2006; Mahner, 2008). We utilized this context to devise a conflict between two departments over the distribution of tuition fees. Specifically, we put students of the psychology department in an advantaged position, with their department allegedly having more money at its disposal due to a higher number of students, compared to the history department. The psychology department then put forward an equity claim which was in conflict with the history department’s neediness claim. We tested whether the justice-focused intervention would increase the willingness of psychology students to make financial concessions to the history department.

Complete material, data, and scripts are available here https://osf.io/vw3fu/.

Study 1

Method

Sample and Design

Ninety-two students (24% male, Age M = 22.18, SD = 5.06), enrolled in the Department of Psychology at a Bavarian university, participated in the study.

Five participants indicated that they did not pay tuition fees. Their data were omitted from analyses because it could be assumed that they were less personally concerned with a redistribution of tuition fees. The data of six further participants were omitted from analyses because they were enrolled in both departments, and, thus, did not exclusively belong to one of the conflict parties.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three experimental conditions [i.e., justice-focused intervention, n = 29 (17% men, age M = 22.71, SD = 8.37); empathy intervention, n = 24 (25% men, age M = 21.54, SD = 2.11); or control group, n = 28 (25% men, age M = 22.25, SD = 2.88)].

The sample size was partly determined by the fact that German psychology tracks are traditionally small, resulting in a small population of psychology students. We computed sensitivity analyses for the central analyses with G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) which indicated that with N = 81 and a critical α of 0.05, we obtained test power of 1-β = 0.80 for main effects with effect sizes of f = 0.35 (between-subjects ANOVA with three groups), f = 0.18 (mixed ANOVA with three groups and two levels on a repeated measure), and d = 0.70 (t-tests).

Procedure

The study was introduced as a survey on tuition fees conducted by psychology students. Students from the psychology department were approached individually on campus. If they agreed to participate in the survey, they received a paper-based questionnaire, which took about 15 min to fill out. This questionnaire first introduced an allocation conflict between the psychology department and the history department. Depending on experimental conditions, this information was followed by a conflict intervention or no further information. Then, the dependent measures were assessed, followed by control and demographic variables. Finally, participants were probed for suspicion, thanked, and thoroughly debriefed verbally and via a written flyer describing the study’s main purpose. We complied strictly to ethical requirements of the APA.

Material

Introduction of the Allocation Conflict

The questionnaire contained, first, information about an alleged allocation conflict between the psychology department (i.e., participants’ own department) and the history department. It was outlined that the psychology department had more money available from tuition fees than the history department due to higher numbers in students. To be able to provide qualified academic education, the history department demanded a transfer of money from the psychology department (neediness claim). The psychology department, however, argued that its own students deserved their tuition fees to be spent for the improvement of their own study conditions (equity claim).Footnote 1

Interventions

Next, the experimental groups read additional instructions while the control group received no further information (see supplementary material for original wording of instructions). In the justice-focused intervention condition, participants received a short paragraph in which, first, each department’s justice standard was explicated; second, the general dilemma structure of justice issues was explained; and third, examples of situations were provided in which the same person could apply different justice standards.

The empathy induction was adopted from Batson and colleagues (2003). Participants were asked to take the perspective of a student from the history department (imagine-self; Stotland, 1969), to imagine how they would feel, think, and act if they were in the place of this student, and to take a few notes elaborating on their thoughts and feelings.

Dependent Variables

Participants’ legitimacy judgments regarding the claims of the psychology department (in-group’s equity claim) and the history department (out-group’s neediness claim) were assessed with three items each (“What do you generally think about the demand to use your tuition fees for the Faculty of History and the Arts/ solely for the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences?”, 0 (very negative) to 5 (very positive); “How fair or unfair do you find the demand to use your tuition fees for the Faculty of History and the Arts/ solely for the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences?”, -3 (very unjust) to 3 (very just) – recoded to 0 to 5; “Are you angry about the demand to use your tuition fees for the Faculty of History and the Arts/ solely for the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences?”, 0 (not at all) to 5 (very much) – reverse coded). We averaged the responses to the three items for each claim to obtain legitimacy judgments for the in-group’s equity claim (Cronbach’s α = 0.82) and for the out-group’s neediness claim (α = 0.93).

As a measure of concessions to the out-group, participants were asked what percentage of their tuition fees they agreed to transfer to the history department (11-point response scale ranging from 0 to 100% in steps of 10%).

Appropriateness Checks

To ensure that we had selected an appropriate context, we applied four appropriateness checks (using a rating scale ranging from 0 (does not apply at all) to 5 (applies very much): We measured identification with the psychology department, i.e., the in-group, with four items (e.g., “I identify with the psychology department”, α = 0.80; adapted from Doosje et al., 1998). Relevance of the conflict (“How tuition fees are used is very important to me personally.”), familiarity with the history department (“I know the history department very well”), and credibility of our cover story (“It is possible to transfer tuition fees paid in one department to another department”) were assessed with one item each. Further, we asked whether participants paid tuition fees and whether they were (also) enrolled in the history department with dichotomous items. These two items served as exclusion criteria.Footnote 2

Results

Appropriateness Checks

We ensured that the chosen context was sufficiently relevant and credible to participants (see Table 1, left panel, for means, standard deviations, and comparisons to the theoretical scale midpoint). Participants identified with the psychology department (i.e., the in-group) and saw the conflict regarding the allocation of tuition fees as personally relevant. Overall, participants were not familiar with the history department and believed the main aspect of the cover story, that is, that a redistribution of tuition fees was negotiable. Additional explorations of appropriateness checks can be found in the supplementary material.

Effectiveness of Interventions

To evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions, the two legitimacy judgments were submitted to a 3 (Experimental Condition: justice-focused intervention/ empathy induction/ control condition) × 2 (Claim: equity claim/ neediness claim) ANOVA with repeated measures on the second factor. Furthermore, we employed an ANOVA to compare concessions to the out-group between the experimental conditions.

Legitimacy Judgments

We found a significant main effect of experimental condition on the evaluation of claim legitimacy, F(2,78) = 3.46, p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.08. In addition, there was a significant interaction effect of Experimental Condition x Claim, F(2,78) = 7.07, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.15 (see Fig. 1). Consistent with Hypotheses 1a and 1b, post-hoc t-tests (Benjamini–Hochberg corrected; corrected p-values henceforth denoted with pbh)Footnote 3 showed that the out-group’s neediness claim was judged as significantly more legitimate after the justice-focused intervention, t(50.55) = 3.87, pbh < 0.001, d = 1.02, and the empathy induction, t(50) = 4.44, pbh < 0.001, d = 1.23, compared to the control group. Consistent with Hypothesis 2a and 2b, the judgment of the in-group’s equity claim was significantly lower in the empathy induction group, t(50) = −2.46, pbh = 0.03, d = −0.68, but not in the justice-focused intervention group, t(55) = − 1.53, pbh = 0.20, d = −0.40, compared to the control group. However, judgment of the in-group’s claim did not differ between the intervention groups, t(51) = −0.89, pbh = 0.45, d = − 0.25.

Concessions to the Out-Group

The interventions had a significant effect on concessions to the history department, F(2,77) = 5.07, p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.12. Participants in the control condition were substantially less willing to transfer their tuition fees to another department (M = 17.14, SD = 16.52) compared to participants in the justice-focused intervention condition (M = 31.43, SD = 20.13), t(54) = 2.90, pbh = 0.02, d = 0.78, and the empathy condition (M = 31.67, SD = 21.20), t(50) = 2.78, pbh = 0.01, d = 0.77. Concessions in the two intervention groups did not differ significantly from each other, t(50) = − 0.04, pbh = 0.97, d = 0.01.

Mediation Analysis

Did legitimacy judgments mediate the effect of interventions on the willingness to make concessions to the out-group? Using the R-package lavaan (Rosseel, 2012), we conducted a mediation analysis with legitimacy judgments of the in-group’s and out-group’s claims as parallel mediators and justice-focused intervention and empathy induction as predictors (dummy-coded, with control condition coded 0; see Fig. 2). Consistent with Hypothesis 2a, the indirect effect of justice-focused intervention through perceived legitimacy of the out-group’s claim on concessions was significant, B = 14.87, SE = 4.20, 95% CI [6.64, 23.11]. Similarly, in line with Hypothesis 2b, the indirect effect of empathy induction through perceived legitimacy of the out-group’s claim on concessions was significant, B = 16.26, SE = 4.42, 95% CI [7.59, 24.92]. No other indirect effect was significant.

Discussion

Utilizing a realistic conflict setting, we tested the effectiveness of a justice-focused intervention, the qualifying subjective justice views, among members of an advantaged group to mitigate conflict. In line with our hypotheses, both the justice-focused intervention and empathy induction led to higher concessions to the out-group, mediated by judgments of the out-group’s claim as legitimate. At the same time, only empathy induction affected the judgment of the in-group’s claim: Compared to the control group, empathy induction reduced the perception of the in-group’s claim as legitimate. However, this did not appear to negatively affect the willingness to make concessions.

While Study 1 provided initial support for the effectiveness of the justice-focused intervention, we considered it necessary to replicate and extend these findings in a second study.

Study 2

We utilized the same conflict context but implemented three modifications. First, instead of comparing the justice-focused intervention with empathy induced through an imagine-self procedure, we used an imagine-other procedure. The latter has been shown to induce feelings of empathy while the former can induce empathy coupled with personal distress (Batson et al., 1997). Potentially, feeling distressed – rather than empathic – may have affected the judgment of the in-group’s claim in Study 1. Moreover, we added manipulation checks, measuring the understanding of the structure of justice dilemmas as well as experienced empathy. We tested whether they distinctly mediated the effects of the justice-focused intervention and empathy induction to shed light on the hypothesized partly distinct mechanisms underlying both interventions. Lastly, we included a combination condition in which both techniques were applied consecutively to explore potential additive effects. Possibly, experiencing empathy for the out-group could set the stage for, and thus increase the effectiveness of, the cognitively challenging qualifying of subjective justice views.

Method

Sample and Design

In total, 181 students (20% male; age M = 23.55, SD = 6.46), enrolled in the Department of Psychology at a Bavarian university, participated in the study.

Data of 21 participants who did not indicate that they paid tuition fees were excluded from analyses. Furthermore, four participants in the empathy condition, three in the control condition, and two in the combination condition did not follow the instructions to take notes on thoughts and feelings (see below). Their data were excluded because interventions may have been less effective.Footnote 4

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions [i.e., justice-focused intervention (n = 37, 24% men, age M = 22.03, SD = 6.85), empathy induction (n = 36, 19% men, age M = 24.28, SD = 6.55), combination group (n = 44, 21%, age M = 23.39, SD = 5.60), or control group (n = 34, 27% men, age M = 22.88, SD = 5.29)].

With N = 151, a critical α of 0.05, and effect sizes as observed in Study 1 (f ≥ 0.29; d ≥ 0.68) we obtained test power > 0.88 for interactions and main effects, respectively, in the focal analyses.

Procedure

Students were invited to participate in the study at the end of an introductory lecture. The same procedure was applied as in Study 1 with the following exceptions.

Material

Interventions

In the empathy condition, the imagine-other instructions were adapted from Batson and colleagues (2003). Participants were instructed to imagine how students of the history department feel in a situation in which their department is unable to improve teaching conditions due to a lack of tuition fees. Participants were then asked to take notes about the others’ thoughts and feelings.

To parallel these instructions, in the control condition, participants were asked to think and write about their own situation as a student of the psychology department and how they think and feel in a situation in which their own department is supposed to transfer tuition fees to the history department.

Furthermore, a combination condition received first the empathy induction followed by the justice-focused intervention.

Dependent Variables

We used the same items as in Study 1 to assess participants’ legitimacy judgments regarding the in-group’s equity claim (α = 0.80) and the out-group’s neediness claim (α = 0.83). To measure concessions to the out-group, we used two items (adding “What percent of tuition fees should the psychology department transfer to the history department?”, 0% to 100% in steps of 10%; r = 0.71, p < 0.001).

Manipulation Checks

To check whether participants had followed the instructions, we asked “To what extent did you focus on the feelings of students of the history department?” and “To what extent did you focus on your own feelings as a student of the psychology department?” (0 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Two items assessed whether participants had understood the structure of justice dilemmas (e.g., “Both departments have valid justice views”, 0 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree); r = 0.37, p < 0.001).

Experienced empathy and distress with regard to the transfer of tuition fees were assessed by means of 14 adjectives (Batson et al., 1997). Six items served as an experienced empathy index (e.g., “sympathetic”; 0 (not at all) to 5 (very much), α = 0.81) and eight items as a distress index (“alarmed”; α = 0.91).

Results

Appropriateness Checks

As shown in Table 1 (right panel), identification with the in-group and personal involvement with the conflict was high. Also, participants were not highly familiar with the history department and believed the cover story that a redistribution of tuition fees was negotiable. See supplementary material for further exploratory analyses involving these checks.

Manipulation Checks

The four experimental groups did not differ significantly in how much they focused on their own feelings, F(3,147) = 0.64, p = 0.59, ηp2 = 0.01, nor in their distress, F(3,147) = 0.53, p = 0.67, ηp2 = 0.01. However, as intended, groups differed significantly with regard to experienced empathy, F(3,147) = 3.997, p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.08, focusing on the feelings of others, F(3,147) = 14.36, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.23, and understanding of the justice dilemma, F(3,147) = 6.51, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.12. Table 2 displays descriptive statistics for each group and post-hoc t-tests. With regard to understanding the justice dilemma, we found a heightened understanding after the justice-focused intervention and the combination of interventions, compared to the control condition and empathy induction. The understanding of the justice dilemma was, instead, comparable in the control condition and after empathy induction. With regard to empathy, results showed that experience increased after empathy induction and in the combination condition, compared to the control condition. Experienced empathy in the justice-focused condition, however, did not differ significantly from neither the empathy induction nor the control condition.

Effectiveness of Interventions

Legitimacy Judgments

There was a significant interaction of Experimental Condition x Claim on the legitimacy judgments, F(3,147) = 5.16, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.10 (Fig. 3). Subsequent t-tests for each claim showed that the out-group’s neediness claim was judged as significantly more legitimate after the justice-focused intervention compared to the control group, t(69) = 2.47, pbh = 0.048, d = 0.58. Other than expected, the out-group’s neediness claim was not judged as significantly more legitimate after empathy induction compared to the control group, t(62.08) = 1.38, pbh = 0.30, d = 0.33. In the combination group, the neediness claim was judged as significantly more legitimate compared to the control group, t(56.03) = 3.59, pbh = 0.01, d = 0.86, and compared to the empathy group, t(78) = 2.59, pbh = 0.04, d = 0.59. The justice-focused group did not differ significantly from the other intervention groups, ps > 0.26.

Different from Study 1, the judgment of the in-group’s equity claim was not significantly lower in the empathy condition compared to the control group, t(68) = 0.78, pbh > 0.48, d = 0.17. However, in the combination group, the in-group’s equity claim was evaluated as less legitimate compared to the control group, t(76) = 2.82, pbh = 0.04, d = 0.59. The intervention groups did not differ significantly from each other, ps > 0.08.

Concessions to the Out-Group

There was a significant main effect of experimental condition on concessions to the out-group, F(3,147) = 4.68, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.09. Participants in the control group (M = 21.77, SD = 18.95) were significantly less willing to transfer tuition fees compared to justice-focused intervention group (M = 37.03, SD = 26.50), t(69) = −2.77, pbh = 0.04, d = −0.66, and combination group (M = 33.18, SD = 17.19), t(76) = −2.78, pbh = 0.02, d = −0.64, but not compared to empathy condition (M = 25.14, SD = 13.91), t(68) = −0.85, pbh = 0.48, d = − 0.85. The empathy condition also scored significantly lower than the justice-focused intervention group, t(54.77) = −2.41, pbh = 0.04, d = −0.56, and combination group, t(78) = −2.27, pbh = 0.04, d = −0.51.

Mediation Analysis

We extended the mediation analysis from Study 1 as we wanted to know whether effects of the interventions on the legitimacy judgments of the out-group’s claim and concessions were mediated by understanding of the justice dilemma and experienced empathy, respectively. We thus conducted a serial parallel mediation analysis with understanding of the justice dilemma and experienced empathy as a first set of parallel mediators and legitimacy judgments of the out-group’s and in-group’s claim as the second set of parallel mediators (see Fig. 4).

The effect of the justice-focused intervention was specifically and uniquely mediated by heightened understanding of the justice dilemma and perceived legitimacy of the out-group’s claim, B = 1.87, SE = 0.89, 95% CI [0.12, 3.61], and not by increased experienced empathy. Empathy induction had an indirect effect on concessions through experienced empathy and perceived legitimacy of the out-group’s claim, B = 2.49, SE = 1.10, 95% CI [0.33, 4.65], but not via understanding of the justice dilemma. Finally, the combination condition exerted its effects on legitimacy of the others’ claim and consequently on concessions, via both experienced empathy, B = 2.70, SE = 1.11, 95% CI [0.53, 4.87], and understanding of the justice dilemma, B = 2.02, SE = 0.92, 95% CI [0.21, 3.83].

Discussion

Replicating and extending the central findings of Study 1, Study 2 showed that the justice-focused intervention increased the willingness to make concessions among members of the advantaged group, through a heightened understanding of the justice dilemma and legitimacy judgments of the out-group’s neediness claim. Surprisingly, empathy induction through the imagine-other technique did not have a total effect on concessions. Yet, we found evidence for an indirect effect via experienced empathy and legitimacy judgments of the out-group’s claim. Hence, results indicated that indeed both interventions might exert effects through partly distinct psychological mechanisms. A combination of the qualifying of subjective justice views and empathy induction was successful in increasing legitimacy judgments of the out-group’s claim and the willingness to make concessions through both mechanisms, the experience of empathy and understanding of the justice dilemma. However, noteworthily, this combination also reduced legitimacy judgments for the in-group’s claim.

General Discussion

The main goal of the present research was to test the effectiveness of an intervention technique aimed at qualifying subjective justice views (Montada, 2003, 2007) for mitigating intergroup conflicts, by facilitating concessions to the out-group among advantaged group-members. As discrepant justice perceptions can be at the core of escalating conflicts (Kim & Smith, 1993; Mikula & Wenzel, 2000), a justice-focused intervention was tailored to help conflict parties understand the dilemma structure of conflicting justice standards and to present diverging justice perceptions as equally legitimate (Montada, 2003, 2007). Results of two experiments indicated that the justice-focused intervention could be effectively adapted for an intergroup context and yielded insight into the psychological paths through which this intervention exerted its effects. Consistently, the justice-focused intervention increased as how legitimate advantaged group members judged the out-group’s neediness claim and, through this, how willing they were to pay concessions. Crucially, Study 2 suggested that this was indeed driven by an understanding of the justice dilemma, but not experienced empathy. At the same time, the justice-focused intervention did not affect legitimacy judgments of the in-group’s claim. Thus, fostering the understanding of the justice dilemma at the core of an intergroup conflict helps mitigate it.

We further compared the effects of the justice-focused intervention with an established intervention, namely empathy induction, that also addresses concerns of an out-group. Using an imagine-self technique to induce empathy, Study 1 showed that both the justice-focused intervention and empathy induction were similarly effective in increasing the legitimacy judgments of the out-group’s claim and the willingness to pay concessions. However, the empathy induction also led to the devaluation of the in-group’s claim, compared to the control group. In Study 2, unexpectedly, empathy induction through an imagine-other technique did not affect legitimacy perceptions and even led to fewer concessions, compared to the justice-focused intervention. These inconsistencies across studies could be due to the different techniques (i.e., imagine-self in Study 1 and imagine-other in Study 2) but they may also point at potential downsides of empathy induction, in comparison to the justice-focused intervention, which need to be investigated further.

The comparison between intervention techniques further showed that the justice-focused intervention and empathy induction function through partly different psychological mechanisms, namely through a heightened understanding of the justice dilemma or experienced empathy. On a theoretical level, this suggests that the two interventions respectively work via the assumed rather cognitive or emotional routes. On a practical level, this means that the justice-focused intervention could constitute a viable alternative to empathy induction to mitigate conflicts, especially in conflicts in which parties struggle to feel empathy for the out-group (see Cikara et al., 2011). For instance, in highly emotional conflicts, in particular with deep-seated negative emotions, the involved parties may be reluctant to feeling empathy for the out-group. Conversely, in some conflicts, such as professional disputes, an emotional approach to resolution may be seen as inappropriate. Especially in such cases it could be promising to employ the justice-focused intervention to mitigate conflict through a rather cognitive route. Moreover, interestingly, the two individual pathways were both relevant when combining the interventions; hence, the two interventions appear not to be redundant. If suitable in a given conflict context, their respective mechanisms can be combined sensibly for the mitigation of justice conflicts.

Originally developed for contexts of interpersonal conflict mediation (Montada, 2003, 2007), we successfully adapted the qualifying of subjective justice views to mitigate conflict in an intergroup context. Importantly, with short written instructions, interventions were minimal. Thus, our studies suggest that such intervention, directly targeting discrepant justice perceptions at the core of an emerging intergroup conflict, might be useful in various contexts, and are not limited to professional dispute resolution with the assistance of a third party (e.g., mediation).

Limitations and Future Research

While our studies provided consistent evidence for the effectiveness of the justice-focused intervention, some limitations need to be pointed out that may stimulate future research. First, the context we used to investigate our research questions allowed us to construe an emerging conflict between two actually existing groups. However, as mentioned earlier, psychology departments in German universities are traditionally small which restricted the population from which we could draw our samples. Consequently, the statistical power of our analyses was sufficient to detect medium to large effects and some of the effects we found to be significant fell below the effect sizes determined in the sensitivity analyses (Study 1) and used in the power analyses (Study 2). For example, that fact that we did not find differences between the justice-focused intervention and empathy induction in empathy experience may be an issue of power or suggest that the justice-focused intervention enlists some feelings of empathy as a byproduct. Hence, further research is needed to reliably determine potential differences and similarities in the specifics of the intervention techniques. Another methodological aspect that future research should investigate is whether the order of presentation matters when both interventions are applied in combination. While we used a fixed order in the combination condition in Study 2 (first anger induction, followed by the justice-focused intervention), future research could investigate whether the order of presentation affects the effectiveness of such a combined intervention.

Moreover, the specific conflict context in which we tested our hypotheses may have implications for the generalizability of our findings. First, as we used the context of an emerging conflict, additional research is needed to test whether the justice-focused intervention can also be effective in reducing escalated or long-lasting, intractable conflicts. In such situations, often either side of the conflict has developed strong narratives about the conflict which may get in the way of listening to conflicting justice views. Future research should thus explore under what conditions and additional efforts divergent justice views can be reconciled in long-lasting conflicts. Second, while our appropriateness checks ensured that participants identified with the in-group and did not have (close) ties with the out-group, both groups shared an overarching identity, namely, university students. Potentially, if this overarching identity was activated in our studies, it may have facilitated the effects of both interventions. Third, our investigation focused on monetary concessions made by members of an advantaged group. This begs the question whether the justice-focused intervention would also be effective in qualifying justice views in members of disadvantaged groups. This is not only an empirical question but is of political relevance: As perceptions of injustice have been identified as a main driver of collective action (Van Zomeren et al., 2008), qualifying opposing justice claims for members of disadvantaged groups could demobilize collective action. However, as our studies demonstrated that the legitimacy judgments of the in-group’s claim remained largely unchanged by the justice-focused intervention, it may also motivate conciliatory actions, such as dialog, without giving up collective action. Lastly, related to the characteristics of the group under study, it could be tested whether other justice standards (e.g., inborn status) can be qualified in a similar manner to equity vs. neediness claims.

Conclusion

Our research provides first evidence for effective mitigation of intergroup conflict through an intervention technique that directly addresses discrepant justice perceptions. The justice-focused intervention helped members of an advantaged group to acknowledge a dilemma structure inherent in justice conflicts, and consequently increased the perceived legitimacy of the out-group’s claim as a central process, leading to more willingness to make concessions. At the same time, it did not call into question the legitimacy of the in-group’s justice claim. As such, our findings advance the theoretical understanding of conflict mitigation and are of high practical relevance. At least at the emergence of conflicts, this may be an economic, minimal yet effective way of preventing the escalation of conflict.

Notes

In fact, a redistribution of tuition fees from one department to another was not possible. However, results indicated that almost all participants were not aware of this fact.

We provide the results of the analyses with the full sample in the supplementary material.

The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure allows to control the false discovery rate (FDR). That is, it controls the expected proportion of false positives among the rejected null hypotheses and thus provides more statistical power than more conservative procedures that control the probability of at least one false positive across tests (such as the Bonferroni procedure).

As for Study 1, results of the analyses with the full sample are provided in the supplementary material.

References

Barclay, L. J., Skarlicki, D. P., & Pugh, S. D. (2005). Exploring the role of emotions in injustice perceptions and retaliation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 629–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.629

Bar-Tal, D., & Halperin, E. (2011). Socio-psychological barriers to conflict resolution. In D. Bar-Tal (Ed.), Intergroup conflicts and their resolution: A social psychological perspective (pp. 217–239). Psychology Press.

Batson, C. D., & Ahmad, N. Y. (2009). Using empathy to improve intergroup attitudes and relations. Social Issues and Policy Review, 3, 141–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2009.01013.x

Batson, C. D., Ahmad, N., Yin, J., Bedell, S. J., Johnson, J. W., & Templin, C. M. (1999). Two threats to the common good: self-interested egoism and empathy-induced altruism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025001001

Batson, C. D., Early, S., & Salvarani, G. (1997). Perspective taking: Imagining how another feels versus imaging how you would feel. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 751–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297237008

Batson, C. D., Lishner, D. A., Carpenter, A., Dulin, L., Harjusola-Webb, S., Stocks, E. L., Gale, S., Hassan, O., & Sampat, B. (2003). “... As you Would have them do unto you”: does imagining yourself in the other’s place stimulate moral action? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1190–1201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203254600

Čehajić-Clancy, S., Goldenberg, A., Gross, J. J., & Halperin, E. (2016). Social-psychological interventions for intergroup reconciliation: An emotion regulation perspective. Psychological Inquiry, 27, 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2016.1153945

Cikara, M., Bruneau, E. G., & Saxe, R. R. (2011). Us and them: intergroup failures of empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(3), 149–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411408713

Deutsch, M. (1975). Equity, equality, and need: What determines which value will be used as the basis of distributive justice? Journal of Social Issues, 31, 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1975.tb01000.x

Doosje, B., Branscombe, N. R., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. R. (1998). Guilty by association: When one’s group has a negative history. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 872. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.872

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Friedmann, J. (2006). Studiengebühren – Feilschen ums Kleingedruckte [Tuition fees – Bargaining about details]. SPIEGEL Panorama. https://www.spiegel.de/lebenundlernen/uni/studiengebuehren-feilschen-ums-kleingedruckte-a-427821.html

Gollwitzer, M., & Denzler, M. (2009). What makes revenge sweet: Seeing the offender suffer or delivering a message? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 840–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.001

Kim, S. H., & Smith, R. H. (1993). Revenge and conflict escalation in theory. Negotiation Journal, 9, 37–44.

Mahner, S. (2008). Bezahlstudium – Wer bekommt wie viel? [Payed tuition – Who gets how much?]. Die Zeit. http://www.zeit.de/2008/27/C-Gebuehrenverwendung

Mikula, G., & Wenzel, M. (2000). Justice and social conflict. International Journal of Psychology, 35, 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/002075900399420

Montada, L. (2003). Justice, Equity, and Fairness in Human Relations. In I. B. Weiner (Ed.), Handbook of Psychology (pp. 537–568). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471264385.wei0522

Montada, L. (2007). Justice conflicts and the justice of conflict resolution. In K. Törnblom & R. Vermunt (Eds.), Distributive and procedural justice. Research and applications (pp. 255–268). Ashgate/Glower.

Müller, M. M., Kals, E., & Maes, J. (2008). Fairness, self-interest, and cooperation in a real-life conflict1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38, 684–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00322.x

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48.

Rubin, J. Z., Pruitt, D. G., & Kim, S. H. (1994). Social conflict: Escalation, stalemate, and settlement (2nd ed.). Mcgraw-Hill Book Company.

Stotland, E. (1969). Exploratory investigations of empathy. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 271–313). Academic Press.

Törnblom, K., & Kazemi, A. (2012). Advances in justice conflict conceptualization: A new integrative framework. In E. Kals & J. Maes (Eds.), Justice and conflicts (pp. 21–52). Springer.

Van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 504–535. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

Acknowledgements

We thank Leo Montada, Tobias Rothmund, Jane Zagorsky, and Eva Traut-Mattausch for important comments on this paper and Carolyn Jeschke for support in collecting the data.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Statement

The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and APA standards.

Consent to Participate

Consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Availability of Data and Material

Data and material have been made available on OSF https://osf.io/vw3fu/.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sasse, J., Nazlic, T., Alrich, K. et al. Mitigating Intergroup Conflict: Effectiveness of Qualifying Subjective Justice Views as an Intervention Technique in Comparison to Empathy Induction. Soc Just Res 35, 107–127 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-022-00387-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-022-00387-2