Abstract

In this paper we analyse why in some countries the difference in subjective well-being between employed and unemployed young individuals is substantial, whereas in others it remains small. The strength of this relationship has important consequences, hence it affects the intensity of the job search by the unemployed as well as the retention and productivity of employees. In the analysis we are focused on youth and young adults who constitute a group particularly exposed to the risks of joblessness, precarious or insecure employment. We expect that in economies where young people are able to find jobs of good quality, the employment–well-being relationship tends to be stronger. However, this relationship also depends on the relative well-being of the young unemployed. Based on the literature on school-to-work transition we have identified macro-level factors shaping the conditions of labour market entry of young people (aged 15–35), which consequently affect their well-being. The estimation of multilevel regression models with the use of the combined dataset from the European Social Survey and macro-level databases has indicated that these are mainly education system characteristics (in particular vocational orientation and autonomy of schools) and labour market policy spending that moderate the employment–well-being relationship of young individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The detrimental effect of unemployment on well-being (usually proxied by the declared level of life satisfaction or happiness) is very well documented in the sociological, psychological and economic literature (for an overview, see Brand, 2015; Clark, 2018). We can distinguish two main channels through which the employment–well-being relationship is established. The first can be referred to as a direct psychological effect of a job loss on life satisfaction. The theoretical underpinning of this effect draws on the ‘latent deprivation model’ of Jahoda (1982), who identified five functions of professional work: time structure, collective purpose, social contact, social status and activity. These functions satisfy basic human needs helping to sustain individual well-being. On the other hand, the unemployed are deprived of the source of earnings which impairs their happiness. Therefore the second, indirect income effect of unemployment can be identified. Parental and marital status are other characteristics mediating the employment–well-being relationship. Labour market status affects the likelihood to establish family which, in turn, affects life satisfaction. Moreover, the detrimental effect of past unemployment persists regardless of current employment status, which in the literature is referred to as the scarring effect (Clark et al., 2001).

The core assumption of this paper states that job quality strengthens the employment–well-being relationship. We define this concept following Duncan Gallie who identified its five dimensions: skill use at work, work autonomy, opportunities for professional development, job security and work-life balance (Gallie, 2007, p. 6).Footnote 1 Within the so-called ‘bottom-up approach’ general life satisfaction depends on satisfaction with specific life domains, including professional work which, in turn, is influenced by job characteristics (Viñas-Bardolet et al., 2020).Footnote 2 In the extensive literature review Thomas Barnay (2016) showed that job features characterizing practically all dimensions distinguished by Gallie contribute to mental health or subjective well-being. Similar conclusions are presented in the study of Sonja Drobnič et al. (2010) who indicated that subjective well-being of workers increases with employment security, autonomy at work, good career prospects and task variety. Among all facets of employment quality, the moderating effect of job security has been most thoroughly studied (recent research, Viñas-Bardolet et al., 2020, the literature review, De Witte et al., 2015). On the other hand, life satisfaction of the unemployed also affects the employment–well-being relationship. The labour market policy has been the most recognized macro-level factor influencing their well-being (Vossemer et al., 2017; Wulfgramm, 2014).

The aim of the analysis presented in this paper is to verify which factors measured at the country level moderate the relationship between employment status and well-being among young individuals. The strength of this relationship has important consequences, hence it affects the intensity of the job search by the unemployed (see e.g. Mavridis, 2015) as well as the retention and productivity of employees (see e.g. Clark, 2018). It also shows how efficient the labour markets and economies are in providing young individuals with good-quality jobs. We mostly focus on institutional features therefore our paper contributes to a wider group of analyses studying the impact of public policies on well-being (see e.g. Boarini et al., 2013; Vossemer et al., 2017; Wulfgramm, 2014). The contribution of this analysis is twofold. First, we do not focus, as the vast majority of analyses in this field, on all individuals in prime age but on a subsample of people in the age group 15–35. The literature on the employment–well-being relationship is very rich, although rarely focused on young individuals. It is surprising given the fact that youth and young adults constitute a group particularly exposed to the risks of joblessness, precarious or insecure employment (see, e.g. Pastore, 2015; O’Reilly et al., 2015). Some authors claim that disappointments experienced at the beginning of a professional career are responsible for a drop in life satisfaction observed in early adult life (Ferrante 2017). They might have a long-term detrimental impact on well-being (so called ‘scarring effect’). Second, macro-level variables were selected based on school-to-work transition (SWT) literature. Therefore we take into account some institutional characteristics and public policies which were not analysed before (e.g. broad characteristics of education systemsFootnote 3). The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 presents the concept of school-to-work transition and discusses macro-level features potentially moderating the employment–well-being relationship among young individuals, Sect. 3 describes the empirical strategy and the data, and Sect. 4 discusses the results. The last section presents main conclusions.

2 Macro-Level Determinants of Well-Being and the Employment–Well-Being Relationship

In this paper we explain the cross-country variation in the employment–well-being relationship of young individuals by the international differences in SWT patterns. Raffe (2014, p. 177) defines SWT as a ‘sequence of educational, labour-market and related transitions that take place between the first significant branching point within educational careers and the point when (…) young people become relatively established in their labour-market careers’. Raffe mentions various factors shaping national SWT patterns: features of the educational system (standardisation, stratification, educational orientation, and institutional linkages), labour market structure (degree of flexibility and regulation, dominant national form of labour market organisation), labour market policy and other relevant policies, the broader economic environment, family and cultural factors (Raffe, 2008, pp. 284–287). In the remaining part of this section we will refer to most of these factors in order to understand the cross-country variation in the employment–well-being relationship among young people. At the end of each subchapter we formulate our hypotheses on the expected moderating impact of those factors.

2.1 Educational Policy

The institutional features of education systems are characterized along several dimensions. Allmendinger (1989) has identified two of them: the standardisation of educational provisions and the stratification of educational opportunity. The first attribute of the educational system concerns the nationwide standards of education quality. Two forms of this dimension are further distinguished. The standardisation of input refers to the degree of freedom schools have with respect to what and how they teach. In highly standardized educational systems the quality and content of training provided by schools is regulated at the national level. The standardization of output refers to the way the educational performance of students is verified. In highly standardized educational systems the competences of graduates are tested through centralized exit examinations. The stratification of educational opportunity characterizes the selectivity of tracking system in education. High level of stratification of educational opportunity describes those education systems in which students are selected into tracks at an early age and the selection is based on abilities or interests, where the tracks differ in terms of curricula and the mobility between tracks is limited. Another attribute of the educational system refers to its vocational orientation (Shavit & Muller, 2000). In vocationally oriented education systems the proportion of students choosing the vocational track is high and the teaching process of occupation-specific skills includes practical training at the workplace (so-called dual apprenticeship system). Some authors refer to this latter aspect as institutional linkages of the education system (Levels et al., 2014).

Numerous studies offer evidence showing that stratified and vocationally oriented education systems (those with strong institutional linkages with firms in particular) improve the labour market matchFootnote 4 (see Scherer 2005, pp. 428–430) contributing to employment quality at least in three dimensions distinguished by Gallie–skill use at work, work autonomy and job security. This is usually explained with the use of a signalling/credential theory (vocationally oriented or stratified education systems send employers relatively precise information about graduates’ skills) or human capital theory (vocational education equips graduates with skills required by employers). The empirical findings indicate that strong skill- or education-job match of graduates corresponds to a high level of stratification (Andersen & Werfhorst, 2010; Bol & Werfhorst, 2013; Levels et al., 2014). Similar findings with respect to vocational orientation are less conclusive (Andersen & Werfhorst, 2010; Wolbers, 2003). However, the results are stronger if we consider education organized as a dual apprenticeship system (Levels et al., 2014). Further evidence can be found in the analyses of the determinants of employment stability of youth which can be also treated as a measure of match quality. It has been found to correlate positively with vocational orientation (Lange et al., 2014; Shavit & Muller, 2000; Wolbers, 2003, 2007) and stratification (Bol and van de Werfhorst 2013; Shavit & Muller, 2000). Since the relationship between the level of match and employees’ well-being is also well documented (Badillo‐Amador and Vila 2013; Mavromaras et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2015; Zhu & Chen, 2016), we expect that the high level of vocational orientation or stratification strengthens the employment–well-being relationship.

The high standardization of output in the education system should increase educational outcomes since the perspective of an exit examination motivates students, teachers and school authorities. Various studies have confirmed this claim (see e.g. Bishop, 1997; Hanushek & Woessmann, 2010; Woessmann, 2016). On the other hand we can expect a negative correlation between standardization in input and educational outcomes since low school autonomy harms competition between schools decreasing the quality of education (Fuchs & Woessmann, 2007; Horn, 2009; Woessmann, 2016). The level and the quality of education, in turn, increases the likelihood to find employment of a better quality which is well proved in the rich literature on the nonpecuniary returns to schooling (classic studies in economics, see e.g. Duncan, 1976; Lucas, 1977, for the overview, see Gunderson & Oreopolous, 2020; Oreopoulos & Salvanes, 2011). Therefore, we expect that a high level of standardization of output (input) strengthens (weakens) the employment – well-being relationship.

2.2 Labour Market Flexibility

One should expect that strong employment protection increases the difference in well-being between labour market insiders and outsiders by boosting the feeling of job security of employees and by diminishing the chances of the jobless to enter employment. Although there are studies confirming the existence of such a moderating effect (Boarini et al., 2013; to some extent Voßemer et al., 2017), there is a number of empirical analyses showing that employment protection has a detrimental effect on employees’ well-being (Böckerman, 2004; Clark & Postel-Vinay, 2009). It might happen since the higher level of protection increases a cognitive job security (not expecting dismissal) but diminishes a perceived labour market security (expecting to find a comparable job easily) (Hipp, 2016:3). Depending on the relative importance of these two effects, the total impact of employment protection on employees’ well-being can be either positive or negative. However, it is difficult to expect that under high employment protection employees should suffer more than the unemployed. Therefore we expect that employment protection will strengthen the employment–well-being relationship.

2.3 Labour Market Policies

The existing studies suggest that instruments of passive (e.g. unemployment benefits) and active (e.g. professional training) labour market policy (PLMP and ALMP respectively) are beneficial to the unemployed. They not only offer a financial cushion but also have significant non-pecuniary effects. A generous unemployment protection system fights the unemployment stigma, and many active labour market policy measures, like apprenticeship schemes, resemble paid employment and offer intangible benefits similar to those offered by professional work. Therefore, it is hypothesized that labour market policies should weaken the employment–well-being relationship (Wulfgramm, 2014; Voßemer et al., 2017). These analyses, however, abstain from the empirical evidence indicating that in countries with developed LMP also employees declare higher life satisfaction (Clark & Postel-Vinay, 2009; Di Tella et al., 2001; Green, 2011; Hipp, 2016). Many ALMP measures help to bridge the competency gap and generous benefits support the unemployed in their search for jobs that will match their skills. Therefore, both types of LMP contribute to a better quality of employment leading to greater well-being of employees. Since the developed LMP should increase the well-being of both unemployed and working individuals, their moderating effect on the employment–well-being relationship depends on the strength of the effect in these two groups.

2.4 Broader Economic Environment

At the macro level GDP per capita is strongly correlated with the average happiness in nations. On the other hand, the seminal study of Easterlin (1974) indicated that in the USA economic growth had not contributed to the increase in well-being since the end of World War II. The recent findings suggest that subjective well-being is affected by economic growth, however this effect depends on various circumstances (e.g. how the nation’s income growth is divided, Diener et al., 2013; Slag et al., 2019). Inflation and the unemployment rate, i.e. ingredients of the so-called ‘misery index’, are well recognized determinants of well-being. The latter factor has a much more detrimental influence (di Tella et al., 2001). The unemployment rate reduces well-being of both the unemployed and employees. However, it is not clear which group is hit harder. Social comparisons should soothe the determinantal influence of losing a job in areas where the unemployment rate is high (the so-called ‘social norm effect’, Clark, 2003, 2010). On the other hand, the high unemployment rate lowers the perceived employability, decreasing well-being of jobless individuals (Green, 2011). To sum up, the existing literature does not allow to formulate clear predictions how economic conditions moderate the employment –well-being relationship. However, measures of national income and unemployment rate should be considered in the international comparative research on well-being determinants.

2.5 Cultural Factors–a Social Norm to Work

Within this dimension the social norm to work is the most recognized moderator of the employment–well-being relationship. We can expect that in societies which attach a particular value to work, the detrimental effect of unemployment on well-being will be stronger. Jobless individuals in societies with a strong norm to work are more likely to be exposed to informal social sanctions (e.g. gossiping) and experience the feeling of guilt. Stutzer and Lalive (2004) indeed found such moderating effect using the results of a referendum deciding on the level of unemployment benefits as a proxy. This effect has been also observed when the social norm to work was operationalized with the use of survey questions concerning the value of work ethic (Eichhorn, 2014; Roex & Rözer, 2018).

2.6 Transition Regimes and Clustering of macro-level factors

Most of the abovementioned features are interdependent and various characteristics of SWT tend to cluster forming the so-called ‘transition regimes’. The most prominent typology distinguishes five regimes: employment-centred, liberal, universalistic, sub-protective and post-communist (Pohl & Walther, 2007; Walther, 2006). In the employment-centred transition regime fitting the cases of German-speaking countries as well as France and the Netherlands to a certain extent (see Tamesberger, 2017), the educational system is highly tracked and selective. Vocational education often combines school- and firm-based training (dual-apprenticeship system) offering strong institutional linkages with employers. The features of this education system favour employment of graduates and strengthen education-job match. High employment protection combined with moderately developed (at least with comparison to Nordic countries) ALMP limits the employment prospects of unemployed graduates who have not experienced a smooth school-to-work transition. The liberal transition regime is typical for Anglo-Saxon countries. The schooling system is inclusive, not stratified, offering mostly general education which is not institutionally linked to the labour market. ALMP is not developed and aims at fast employment. The level of unemployment benefits is low and they are conditioned by job-search activities. The low level of employment protection increases employment insecurity of graduates, however does not discourage employers to hire young individuals. It results in dynamic flows between labour market states and instability of employment at the beginning of professional career. Nordic countries (and Belgium to a certain extent) (see Tamesberger, 2017) represent the universalistic transition regime. In this cluster the schooling system is inclusive, not stratified, and offers access to higher education to a vast majority of graduates. The employment protection is relatively low although significantly higher than in countries representing the liberal regime. However, the lower employment security is offset by highly developed active and passive LMP (so called ‘flexicurity model’). In the sub-protective regime typical for many Mediterranean countries the schooling system is neither selective nor stratified, with the focus on general education. Vocational training is moderately developed and mostly school-based. Therefore the institutional linkages with employers are limited. High level of employment protection combined with underdeveloped LMP makes it difficult to enter the core segment of the labour market forcing many young individuals to accept peripheral and precarious jobs. The post-communist cluster is represented by the heterogeneous group of CEE countries which has some features of sub-protective and employment-centred regimes. However, the transition systems in CEE countries have little in common.

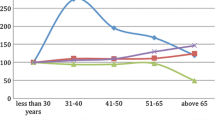

Figure 1. shows patterns of the employment–well-being relationship represented by differences in the average life satisfaction between employed and unemployed young individuals. Countries are sorted in a descending order according to the well-being gap. In many cases the size of the gap coincides with the transition regime type confirming that the macro-level factors might moderate the employment–well-being relationship. The biggest gap is observed in countries representing the employment-centred regimes (DE, CH, AT) where the employment quality of young people is high due to the developed vocational system, strong institutional linkages and employment protection. However, for those who are not successful in the school-to-work transition process, the employment entry might be difficult. In countries representing the universalistic regime a well-being gap is smaller and life satisfaction of both employees and the unemployed is high (best seen in DK, NO, FI) which might be a merit of the flexicurity model. The low well-being gap is noticeable also in countries representing the sub-protective regime (in IT, GR, PT in particular). Contrary to Nordic countries, life satisfaction of both the unemployed and employees is considerably lower which might reflect low employment quality of young individuals and underdeveloped LMP measures. Perhaps for the same reason a similar pattern can be observed in GB representing the liberal model, however in IE the well-being gap is much larger. As discussed earlier, the post-communist cluster consists of countries with various transitions systems, which is reflected by heterogeneity in terms of the well-being gap.

3 Data and Methods

3.1 Micro-Level Variables

The micro-level variables come from the European Social Survey (ESS), which is a project offering high-quality comparative data covering a broad range of European countries. The study has been organized on a biennial basis since 2002. Table 1 presents the detailed description of the micro-level variables used in the study.

The dependent variable (life satisfaction) reflects only one, cognitive dimension of subjective well-being. The affective dimensions (positive and negative emotions) are excluded from the analysis, which is a common practice in socio-economic research. The theoretical framework of this study does not concern self-employed or inactive individuals, therefore we included only employees (regardless of the contract type or working time) and the unemployed in the sample. Due to numerous missing values and inconsistent coding of income groups in ESS, the proxy for income was created based on the respondents’ assessment of financial status. Our focus is on the direct psychological impact of employment status on well-being thus we included the mediating variables proxying other, indirect channels of that relationship (income, parental and civil status). Other independent variables are treated as confounders, which are correlated both with well-being and employment status, and were therefore included in the model to calculate the unbiased effects. Moreover, unemployment in the past reflects the so-called ‘scarring effect’–a determinantal influence of the past unemployment on present well-being regardless of the current employment status.

3.2 Macro-Level Variables

Table 2 presents the macro-level variables used in all models as well as the summary of their hypothesised moderating impact on the employment–well-being relationship. The set of employment protection indices comes from the OECD and the database of Avdagic (2012, 2015) who calculated EPR and EPT indicators for many CEE countries according to the OECD (2020a) methodology. In order to increase the comparability, LMP spending was expressed as a share of GDP and normalized by unemployment rate to account for cross-country differences in demand for such policies.Footnote 5

Table 3 includes additional macro-level variables which will be analysed only in one group of models (due to the data constraints) as well as the summary of their hypothesised moderating impact on the employment–well-being relationship. The scales of sub-indices characterizing the level of stratification and standardization of input were aligned. Therefore, the higher values of STRAT and STANDIN variables indicate the higher level of tracking and standardization of input respectively. The STANDOUT index is a dummy variable with a limited variance (in general, the lack of central exit exams is typical for some Mediterranean countries and for most federal states, i.e. Belgium, Switzerland, or Austria) and will be treated with caution. The index of a social norm to work is a country-level average score for five questions of the World Values Survey on a 1–5 scale: ‘To fully develop your talents, you need to have a job’, ‘It is humiliating to receive money without working for it’, ‘People who don’t work become lazy’, ‘Work is a duty towards society’, ‘Work should always come first, even if it means less free time.’ Such variable is a popular proxy of a social norm to work (for the overview, see Stam et al., p. 315). The study of Eichhorn (2013, p. 1667) confirmed that all these items indeed load on one factor. All variables except STANDOUT (a binary variable) are standardized with the mean value of 0 and the standard deviation of 1.

3.3 Empirical Strategy

In the empirical part of the analysis we use hierarchical regression techniques. This strategy allows to avoid the underestimation of standard errors when variables at different levels of aggregation are combined (Moulton, 1986). In particular we apply two types of models accounting for three- and two- level hierarchy respectively. First, we apply a three level random intercept modelFootnote 6 where individuals are nested within country-years and countries:

where,

\({y}_{ijt}\): a well-being proxy: a level of life satisfaction (0–10) of an individual i in country j in year t,

\({E}_{ijt}\): employment status of an individual i in country j in year t: 1 – employee, 0 – the unemployed, other – excluded,

\({X}_{ijt}\): a set of individual-level control variables (described in Table 1).

\({I}_{jt}\): macro-level variables (features of SWT).

\({E}_{ijt}{I}_{jt}\): interaction term between employment status and a macro-level variable.

\({u}_{ijt},{\varepsilon }_{jt},{e}_{j}\): error terms at individual, country-year and country level.

\(M\): time variable (year).

Despite the fact that the dependent variable’s scale is ordinal, we treat it as the interval one, following the recommendations of Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004), and estimate the linear model where \({\beta }_{pq}\) is the most important parameter. The positive value of this coefficient indicates a larger well-being divide between the employed and the unemployed, hence a stronger employment–well-being relationship.

In the three-level models we analyse only a set of macro-level variables presented in Table 2. The extended set of contextual variables (presented in Tables 2 and 3) was available only for one year (2008). For this data we apply two-level random intercept models where individuals are nested within countries:

The specification described in Eq. (2) is a two-level equivalent of model (1). In this case, parameter \({\beta }_{pq}\) is again most important and concerns the interaction term between individual employment status and a macro-level variable. The interpretation of its values remains the same as in model (1).

The empirical strategy is determined by the limitation of the sample size at higher levels (country-years, countries). Results of the simulations indicate that the minimum number of cases allowing to calculate unbiased coefficients and standard errors ranges between 15 and 25 for simple models (Bryan & Jenkins, 2016; Stegmueller, 2013). Therefore, we add macro-level variables carefully applying a step-wise procedure,Footnote 7 which is a popular empirical strategy used in such cases (see, e.g. Chung, 2016). First, we estimate models described by Eq. (1) with a full set of micro-level variables but only one macro-level variable (and the interaction term with the employment status) at a time.Footnote 8 In the next step we repeat this procedure controlling additionally for GDP and UNEMP. In the third step we add to the specifications the second macro-level variable (with the interaction term) controlling for GDP and UNEMP. Due to the limited number of observations at the macro level, models described by Eq. (2) are calculated even more carefully. First, we analyse specifications with one macro-level variable at a time (with the interaction term). In the next step we additionally control for GDP or UNEP. Finally we analyse models with two macro-level variables (with interaction terms) without controlling for economic conditions (GDP, UNEMP). The applied step-wise procedure allows for inspecting the robustness of the results in case of limitation of macro-level variables which can be included in the models. Under another robustness check we estimate a non-hierarchical version of model (1)–a pooled linear model with country and year fixed effects with standard errors clustered at the country level. Such model emphasizes more within- (over time) than cross-country variation in estimation of effects. The detailed specification of that model is presented in supplementary materials.

3.4 Methodological Challenges

The outlined empirical strategy bears some further methodological issues: reversed causality, omitted variable and overcontrol bias. The first problem is probable in our model since not only unemployment affects well-being but also unhappy individuals are less likely to find/maintain employment (Böckerman & Ilmakunnas, 2012; Oswald et al., 2015). The omitted variable bias will occur if we do not control for all differences (affecting well-being) between employees and the unemployed. In studies investigating the employment – well-being relationship, the empirical strategies addressing these two problems are similar and include the instrumental variable (IV) approach (plants closures are popular instruments, see e.g. Kassenboehmer & Haisken-DeNew, 2009; Marcus, 2013) or panel data regression techniques (Winkelmann & Winkelmann, 1998). The dataset used in this analysis does not contain good candidates for instrumental variables, and its cross-sectional structure precludes the application of panel data models. Therefore the estimation is vulnerable to both types of the above-mentioned bias. However, there are at least three arguments supporting our empirical strategy. First, the paper is focused on international differences in the employment – well-being relationship. Even if the estimated impact of employment status on well-being can be biased, we assume that the size of the bias is similar in all analysed countries. Second, it is difficult to compare IV estimates internationally since they represent the effects calculated for a subgroup affected by the instrument, not for the entire sample. These subgroups might differ internationally. Third, currently there are no international longitudinal micro-level datasets allowing to conduct similar analyses applying panel data models. Therefore most comparative studies on macro-level determinants of well-being use cross-sectional datasets (see e.g., Boarini et al., 2013; Calvo et al., 2015; Vossemer et al., 2017; Wulfgramm, 2014). The overcontrol bias arises when the model controls for characteristics lying on the causal pathway between the independent variable of interest (in our case – employment status) and the dependent variable (well-being). In our setting income, marital and parental status are such potentially mediating variables, and including them in the model reduces the estimated impact of employment status. Therefore some authors prefer more parsimonious models (e.g. Voessemer et al. 2017). In the theoretical part of the analysis we mainly refer to the psychological influence of employment status on well-being (which we consider the main and direct effect), therefore we decided to control for other indirect effects (income, parental and civil status).

3.5 Sample

The theoretical part of this analysis concerns the unemployed and employees. Studies on transition between other states (e.g. employment–inactivity) are built up on different theoretical grounds. Moreover, as noted by Vossemer et al., (2017, p. 1236) the anticipated moderating effects of policies (e.g. employment protection) often do not apply to the group of self-employed. For this reason analyses in this field of interest are either focused on differences between employees and the unemployed (Eichhorn 2013, 2014; Vossemer et al., 2017) or include other groups (e.g. inactive) but do not formulate hypotheses nor interpret results referring to them (e.g. Clark & Oswald, 1994; Stam et al., 2016; Wulfgramm, 2014). Therefore we restrict our sample to employees and the unemployed only. Our sample consists of individuals aged 15–35. Such strategy is driven by the thematic scope of the analysis but also reduces the bias resulting from possible changes of education systems in time (micro-level characteristics are not lagged with respect to variables characterizing education systems). The final sample includes countries for which the full set of micro- and macro-level variables was available. In rare cases, at the macro level the missing values were substituted with values from the nearest year (see table S5 in supplementary materials). The final sample used in the three-level models covers 7 waves of ESS (2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014) and consists of 39,665 individuals from 27 countries. In the estimation of the two-level models we use the data from wave 2008 describing 6990 individuals from 22 countries. Tables 10, 11 in the Appendix and S1-S2 in supplementary materials present the micro- and macro-level descriptive statistics for both samples respectively.

4 Results

Table 4 presents the estimation results of the first-step regressions (where only one macro-level variable and its interaction term with employment dummy were included). The estimated micro-level effects are in accordance with the theoretical expectations. Working individuals declare on average 0.5–0.6 units higher life satisfaction than the unemployed. This result can be attributed to the direct psychological effect since the models control for characteristics potentially mediating the employment – well-being relationship, income, civil and parental status. The results confirm the existence of the scarring effect – regardless of the current labour market status, those who experienced unemployment in the past declare lower life satisfaction. In accordance with the literature, the relationship between age and life satisfaction is strong and non-linear (a statistically significant coefficient of age and its quadratic term). A significant and positive impact of the level of education is not unusual. However, it could also reflect the imperfect measurement of the income variable (strongly correlated with education). The effects of other mediating variables (parental, civil status) as well as confounders (disability, migrant status) are consistent with the current state of knowledge.

Results confirm that in countries with vocationally oriented education systems the employment – well-being relationship is stronger, particularly if it is organized according to the dual apprenticeship modelFootnote 9 (positive and statistically significant coefficients of interaction between the employment status dummy and VOC and VOCD variables). It accords to the expectations since such education systems offering hands-on experience for students and screening opportunities for employers increase the education-job match and employment quality of young individuals. The results indicating the stronger employment – well-being relationship in countries with a generous labour market policy can be interpreted in a similar way (both ALMP and PLMP contribute to the education- or skill-job match). However, contrary to the expectations, the general effects of these variables turned out to be insignificant suggesting that the well-being of the unemployed was not affected by LMP spending. It is less surprising with respect to the PLMP since all models control for household income. The insignificance of ALMP among the unemployed does not follow expectations, however, a similar lack of effect was already reported by other authors studying this topic (e.g. Vossemer et al., 2017). It suggests that ALMP measures do not reflect the conditions of professional employment. Their effects might also be reduced by some selection mechanisms or negative stigma effects. The estimates related to the employment protection legislation do not follow the expectations. Theoretically, we could explain why the stronger protection of regular contracts (EPR) negatively influences well-being of employees (it happens when the negative labour market security effect exceeds the positive job security effect). It is, however, difficult to explain why it does not affect the group of the unemployed or even has a positive impact on their well-being (positive and statistically significant coefficient of the EPT variable). The variance decomposition of the empty model (not reported) indicated that around 13 percent of (unexplained) differences in life satisfaction can be attributed to the country level – the result which is found in similar studies (Vossemer et al., 2017). The estimates presented in Table 4 show that ALMP, PLMP and VOCD best explain that variation (in models with those variables the unexplained variance at the country level amounts to 8 percent).

The unexpected EPT effect disappears once the economic conditions are controlled for (see Table 5) in the second step of the estimations. The other effects remain stable with one noticeable exception. The general effect of VOCD becomes negative indicating decreased well-being of the unemployed in countries with developed dual apprenticeship model of vocational education. In such systems many graduates are hired directly by companies in which they were employed as apprentices. It deteriorates the prospects of the unemployed and might harm their well-being. The economic conditions affect life satisfaction in accordance with expectations. In general, well-being is higher in richer countries and in economies not suffering from unemployment. The economic conditions explain well the international differences in life satisfaction. Adding GDP and unemployment rate to the model reduced unexplained country-level variance to less than 5 percent.

Under a robustness check we estimated a non-hierarchical version of models presented in Table 5, i.e. pooled linear models with country and year fixed effects and standard errors clustered at the country level. The estimated results are very similar – the moderating effects of VOCD and ALMP remain statistically significant (although at lower levels), other interaction effects have the same signs but became insignificant (results are presented in Table S7 in supplementary materials).

The motivation for the last round of estimations is the phenomenon of institutional complementarity (Hall & Soskice, 2001) which can lead to correlation between macro-level variables (see Table 6). For instance, the institutional complementarity may explain the correlation between vocational orientation, employment protectionFootnote 10 and LMP spending. Since vocational education leads to acquisition of specific human capital (productive only in a limited number of sectors), it is considered to be a more risky human capital investment. Therefore it requires some incentives in the form of institutional arrangements. High employment protection secures the return to human capital, generous PLMP gives the opportunity to search for jobs matching specific competences and ALMP covers some costs of retraining.

In order to avoid the potential omitted variable bias at the macro level, we analyse two macro-level institutional variables in the same model. We consider only the most correlated pairs of the variables (bolded in Table 6). The results of seven separate regression models with different combinations of institutional variables are presented in Table 7. The most stable coefficients concern the VOCD variable. Regardless of the specification of the model in countries with developed system of dual vocational education the employment – well-being relationship is stronger. In line with expectations generous labour market policy (both passive and active) as well as vocational orientation increase the difference in well-being between employees and unemployed. However, the results with respect to these variables are slightly less stable. Consequently, the hypotheses are not confirmed for employment protection proxies.

The following tables present estimations of Eq. (2) which included the extended characteristics of education systems as well as proxies for cultural factors (social norm to work). Those variables, however, were only available for the year 2008. Table 8 presents the estimates of the two-level random intercept models including one macro-level variable (top panel), additional control for GDP (middle panel) and UNEMP (bottom panel). The effects of the micro-level determinants are practically the same as in the three-level models and have not been reported. The effects of the already considered institutional features (labour market policy, employment protection legislation, and vocational orientation) were also very similar (see Table S3 in supplementary materials). Out of three additional proxies characterizing the education system only the effects of input standardization (STIN) follow expectations. In countries where the standardization is weaker, i.e. schools have more autonomy with respect to how to teach, the employment – well-being relationship is stronger. The analysis of variance suggests that STIN is the feature of the education system that best explains the differences in well-being at the macro level (highest reduction in unexplained country-level variance). The coefficients of standardization of output and stratification have the predicted signs however are statistically insignificant.

Contrary to expectations in countries with a stronger social norm to work (NORM) the employment – well-being relationship was weaker. The estimated effect was statistically significant and relatively stable across various model specifications. It is difficult to justify this finding, however, we suggest a potential explanation which could be tested under a separate study. The analysis of Stutzer and Lalive (2004) proved that in countries with a strong social norm to work, the unemployed used to find jobs quicker. It accords to the model proposed by Dos Santos Ferreira et al. (2015) in which a strong social norm to work decreases the reservation wage. Therefore a societal pressure can force the unemployed to accept jobs of lower quality. Moreover, a strong social norm to work may also distort the work-life balance. These processes can weaken the employment – well-being relationship.

In the last step we analysed models including the correlated pairs of macro-level variables. We conducted that analysis focusing on the proxy for standardization of input since only that effect followed the expectations and was stable across various model specifications. The coefficients presented in Table 9 confirm the robustness of the results indicating that high standardization of input reduces the employment – well-being relationship. All four sub-indices comprising that synthetic variable contributed to that effect (see Table S4 in supplementary materials).

5 Conclusions

The analysis presented in this paper confirmed that many features of SWT systems explain why in some countries employment status of young individuals is strongly correlated with their well-being, whereas in others the difference in life satisfaction between the unemployed and employees is small. We assume that it depends on the extent to which the SWT systems provide young adults with access to jobs of good quality. On the other hand, the impact of SWT features on life satisfaction of the unemployed also matters. Our analysis suggests that vocationally oriented education systems, particularly those organized as a dual apprenticeship model, strengthen the employment – well-being relationship. This result conforms to the allocative function of education. Vocational education, at least in a short-term perspective, strengthens the education-job match increasing employment quality at least in three aspects: skill use at work, work autonomy, and job security. However, it has to be emphasised that the vocational orientation of education systems, particularly those with strong institutional linkages with firms might have a negative impact on life satisfaction of the unemployed. In such systems many graduates are hired directly by companies which have employed them as apprentices. It reduces the chance of finding employment through the labour market. The level of input standardization measuring the autonomy of schools with respect to what and how they teach, is another feature of the education system moderating the employment – well-being relationship. According to expectations in highly standardized education systems the employment – well-being relationship was weaker. It is compatible with other research findings suggesting that more autonomy of schools boosts the quality of education. This in turn increases the likelihood of graduates to find employment of higher quality. Positive moderating effects were also observed with respect to active and passive labour market policy spending. LMP measures perform the allocative function (like education) increasing the education- or skill-job match and contributing to the well-being of employees. We indicated that it was theoretically sound to expect that the LMP influences not only the well-being of the unemployed (as hypothesized by Vossemer et al., 2017 and Wulfgramm, 2014) but also of employees. That latter relationship was confirmed empirically.

Contrary to our hypotheses, the LMP spending was not positively correlated with life satisfaction of the unemployed. The lack of impact of PLMP measures (e.g. unemployment benefits) might be justified since our models controlled for income. The lack of effects of ALMP might suggest that its measures (e.g. internships) do not reflect the conditions of paid employment as expected or the selection mechanisms biasing the results are at play: the effective ALMP increases the inflow to employment leaving a subset of those least employable in the population of unemployed. Their specific characteristics, for example the level of disappointment, might offset the positive influence of ALMP spending. This possible selection mechanism, as well as potential stigma effects, are worth further investigation.

This paper is another analysis contributing to our understanding of public policy impact on life satisfaction. With the increasing availability and quality of subjective well-being indicators (e.g. OECD Better Live Initiative), the body of research in this area is steadily growing. The development of studies in this field seems natural since one of the main goals of public policy is to influence the well-being of citizens. The validity of subjective well-being as a policy evaluation criterion has been recognized by Romina Boarini and co-authors who empirically proved that it is policy amenable (Boarini et al., 2013). To date, the impact of selected policies has been analysed from this perspective in the areas of health (Boarini et al., 2013; Calvo et al., 2015), employment (Vossemer et al., 2017) and labour market (Vossemer et al., 2017; Wulfgramm, 2014). The analysis conducted in this paper enriches the above body of work by recognizing the impact of a new group of instruments, from the sphere of education policy in particular. Moreover, it verifies the impact of the already analysed policies on the well-being of young people. They constitute a specific group particularly vulnerable to job insecurity, precarious working conditions and unemployment.

More specifically, our analysis contributes to the rich literature investigating labour market outcomes of SWT systems. Studies in this field analyse the impact of various SWT features on such outcomes as education-job match, youth unemployment rate, length of job search, employment stability and occupational status of young adults. We enrich this branch of literature studying how a broad range of SWT characteristics influence the strength of the employment – well-being relationship which could be considered an indirect proxy for job quality. As mentioned above, this study can be perceived as a particular evaluation of public policies, where their impact on life satisfaction is the main assessment criterion. What can we learn from this evaluation?

Vocational orientation, autonomy of schools and developed LMP increase life satisfaction of young employees. The contemporary evidence shows that the well-being of workers is positively correlated with their productivity, retention, and mental and physical health (Clark, 2018, pp. 258–259). Some of these benefits take the form of positive externalities. Their existence is the traditional economic argument supporting state interventions. Moreover, according to the economic theory, the stronger the employment – well-being relationship is, the deeper the utility gap associated with the job loss becomes. This, in turn, increases the motivation of the unemployed to intensify their job search effort. This line of reasoning has been confirmed empirically (Gielen & van Ours, 2014; Mavridis, 2015). However, it cannot be extrapolated without limits. A very weak employment – well-being relationship might be in fact associated with voluntary unemployment (see, e.g. Blanchflower, 2001) while an extensive well-being gap can also have potentially adverse effects (Deter, 2021). Low life satisfaction of the unemployed might lead to discouragement, lower levels of skill acquisition or poorer performance in job interviews (Anderson, 2009, p. 348). That is why the evaluation of all relevant policies should address possible contrasting well-being effects in various groups. To make things even more complex, we should keep in mind that the macro-level factors studied in this paper are not independent but correlate as a consequence of institutional complementarity, forming a limited set of transition regimes.

The analysis presented in this paper has its limitations. The estimation of the employment – wellbeing relationship with the use of cross-sectional data is potentially prone to reversed causality or omitted variable bias as discussed in Sect. 3.4. The macro-level indicators used in the analysis tend to be relatively constant over time. This is typical for variables characterizing institutional arrangements since radical reforms are rarely implemented. Therefore, the estimated effects were identified through international comparisons rather than changes in indicators’ values over time. This also increases the risk of biasing the results by omitted variables, this time—at the macro level. In the conducted analysis, however, efforts were made to reduce this risk by using a step-wise approach and thorough examination of the effects of different combinations of variables at the macro level. Moreover, the estimation of the pooled model emphasising within-country changes (over time) in effects estimation confirmed the robustness of results, in particular with respect to ALMP and VOCD. It should be also highlighted that due to the data constraints macro-level variables were characterized at the national level, whereas there is evidence that SWT systems might be shaped at the regional level (Scandurra et al., 2021a). Finally, this paper, similarly to the majority of studies in this field, is mainly focused on supply-side determinants of the labour market. The better understanding of transition systems requires studying also the impact of demand-side factors reflecting the employers’ perspective (Scandurra et al., 2021b, p. 853). This topic paves the way for further scientific exploration.

Availability of data

The final dataset combining micro- and macro-level data (STATA format).

Code availability

STATA do-file for running final regressions and descriptive statistics.

Notes

For other definitions of employment quality, see Boccuzzo and Gianecchini (2015)

As pointed by Drobnič et al. (2010) this picture is probably more complex. The specific life domains are interdependent through spill-over and compensation mechanisms. Regardless of the actual structure of this relationship, various studies indicate that job quality contributes to life satisfaction.

To the best of our knowledge the paper of Högberg et al. (2019) is the only study focused on the moderating role of education policy. However, that study has been built up on different theoretical grounds and considered a narrower group of variables characterizing education systems.

In the literature there is a distinction between skill and educational mismatch. The former term refers to discrepancies between workers’ actual skills and skills required at the workplace while the latter to similar discrepancies with respect to formal education. In a recent paper Hanushek et al. (2017) showed that early employment gains from vocational education can be offset by reduced adaptability questioning the efficiency of vocational education in the lifetime perspective. However, in this paper our focus is on young people at the beginning of their professional careers.

To adjust for the possible low coverage of LMP measures among young individuals, also other variants of ALMP and PLMP variables were used in regressions (ALMP and PLMP variables were additionally multiplied by the coverage rate in the age group < 25). Regardless of the LMP variables’ variants, the results remain basically the same (see Table S6 and comments in supplementary materials).

According to Schmidt-Catran and Fairbrother (2016), optimally, the country-year level should be nested both in a country and in a year level. Such models are often computationally challenging. Therefore, specification with additional control for the year of the analysis (as presented in Eq. 1) is recommended (see Voessemer et al. 2017, Wulfgramm 2014).

It refers to the procedure in which macro-level variables are added to the model gradually, one by one. It is not related to procedures typical for simultaneous equations models or structural models.

The estimated models differ only with respect to the macro-level variable included in the specification.

The difference in effects strength does not result from the difference between samples used in both specifications of the model (due to the data constraints the model with the VOCD variable is estimated in a smaller group of countries). Models including VOCD and VOC variables estimated for the same samples show very similar results.

The negative correlation between EPT and vocational orientation seems to contradict this logic. It is however consistent with the arrangements of the employment-centred regime where protected core of the labour market is accompanied by unprotected peripheries (Gallie, 2007, p. 17). Such model is typical for example in Germany or Austria, which are countries with well-developed vocational education systems.

References

Avdagic, S. (2012). Database of employment protection reforms in Central and Eastern Europe, 1990 2009. UK Data Service ReShare, http://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/id/eprint/850598

Allmendinger, J. (1989). Educational systems and labor market outcomes. European Sociological Review, 5(3), 231–250.

Andersen, R., & Werfhorst, H. G. V. D. (2010). Education and occupational status in 14 countries. The British Journal of Sociology, 61(2), 336–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2010.01315.x

Anderson, C. J. (2009). The private consequences of public policies: Active labor market policies and social ties in Europe. European Political Science Review, 1(3), 341–373. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773909990130

Avdagic, S. (2015). Does deregulation work? Reassessing the unemployment effects of employment protection. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 53(1), 6–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12086

Badillo-Amador, L., & Vila, L. E. (2013). Education and skill mismatches: Wage and job satisfaction consequences. International Journal of Manpower. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-05-2013-0116

Barnay, T. (2016). Health, work and working conditions: A review of the European economic literature. The European Journal of Health Economics, 17(6), 693–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-015-0715-8

Bishop, J. H. (1997). The effect of national standards and curriculum-based exams on achievement. The American Economic Review, 87(2), 260–264.

Blanchflower, D. G. (2001). Unemployment, well-being, and wage curves in eastern and central Europe. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 15(4), 364–402. https://doi.org/10.1006/jjie.2001.0485

Boarini, R., Comola, M., de Keulenaer, F., Manchin, R., & Smith, C. (2013). Can governments boost people’s sense of well-being? The Impact of Selected Labour Market and Health Policies on Life, 114(1), 105.

Boccuzzo, G., & Gianecchini, M. (2015). Measuring young graduates’ job quality through a composite indicator. Social Indicators Research, 122(2), 453–478.

Böckerman, P. (2004). Perception of Job Instability in Europe. Social Indicators Research, 67(3), 283–314. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SOCI.0000032340.74708.01

Böckerman, P., & Ilmakunnas, P. (2012). The job satisfaction-productivity nexus: A study using matched survey and register data. ILR Review, 65(2), 244–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391206500203

Bol, T., & van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2013). Educational systems and the trade-off between labor market allocation and equality of educational opportunity. Comparative Education Review, 57(2), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1086/669122

Brand, J. E. (2015). The far-reaching impact of job loss and unemployment. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043237

Bryan, M. L., & Jenkins, S. P. (2016). Multilevel modelling of country effects: A cautionary tale. European Sociological Review, 32(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv059

Calvo, E., Mair, C. A., & Sarkisian, N. (2015). Individual troubles, shared troubles: The multiplicative effect of individual and country-level unemployment on life satisfaction in 95 nations (1981–2009). Social Forces, 93(4), 1625–1653. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou109

Chung, H. (2016). Dualization and subjective employment insecurity: Explaining the subjective employment insecurity divide between permanent and temporary workers across 23 European countries. Economic and Industrial Democracy. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X16656411

Clark, A. E. (2003). Unemployment as a social norm: Psychological evidence from panel data. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(2), 323–351. https://doi.org/10.1086/345560

Clark, A. E. (2018). Four decades of the economics of happiness: Where next? Review of Income and Wealth, 64(2), 245–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12369

Clark, A., Georgellis, Y., & Sanfey, P. (2001). Scarring: The psychological impact of past unemployment. Economica, 68(270), 221–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0335.00243

Clark, A., Knabe, A., & Rätzel, S. (2010). Boon or bane? Others’ unemployment, well-being and job insecurity. Labour Economics, 17(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2009.05.007

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1994). Unhappiness and unemployment. Economic Journal, 104(424), 648–659.

Clark, A., & Postel-Vinay, F. (2009). Job security and job protection. Oxford Economic Papers, 61(2), 207–239. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpn017

de Lange, M., Gesthuizen, M., & Wolbers, M. H. J. (2014). Youth labour market integration across Europe. European Societies, 16(2), 194–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2013.821621

De Witte, H., Vander Elst, T., & De Cuyper, N. (2015). Job insecurity, health and well-being. In Sustainable working lives: Managing work transitions and health throughout the life course (pp. 109–128). New York, NY, US: Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9798-6_7

Deter, M. (2021). Hartz and minds: Happiness effects of reforming an employment agency. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(4), 1819–1838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00297-7

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2001). Preferences over Inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness. American Economic Review, 91(1), 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.1.335

Diener, E., Tay, L., & Oishi, S. (2013). Rising income and the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030487

Dos Santos Ferreira, R., Lloyd-Braga, T., & Modesto, L. (2015). The destabilizing effects of the social norm to work under a social security system. Mathematical Social Sciences, 76, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mathsocsci.2015.04.004

Drobnič, S., Beham, B., & Präg, P. (2010). Good job, good life? Working conditions and quality of life in Europe. Social Indicators Research, 99(2), 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9586-7

Duncan, G. J. (1976). Earnings functions and nonpecuniary benefits. The Journal of Human Resources, 11(4), 462–483. https://doi.org/10.2307/145427

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and Households in Economic Growth (pp. 89–125). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-205050-3.50008-7.

Eichhorn, J. (2013). Unemployment needs context: How societal differences between countries moderate the loss in life-satisfaction for the unemployed. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(6), 1657–1680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9402-y.

Eichhorn, J. (2014). The (Non-) effect of unemployment benefits: Variations in the effect of unemployment on life-satisfaction between EU countries. Social Indicators Research, 119(1), 389–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0474-9

Eurostat. (2020a). LMP expenditure by type of action, [access: 12.11.2020] https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/empl/redisstat/databrowser/view/LMP_EXPSUMM/default/table?lang=en

Eurostat. (2020b). Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey), [access: 12.11.2020] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/lfs/data/database

EVS. (2015). European values study longitudinal data file 1981–2008 (EVS 1981–2008). GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA4804 Data file Version 3.0.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.12253

Ferrante, F. (2017). Great expectations: The unintended consequences of educational choices. Social Indicators Research, 131(2), 745–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1268-7.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How Important is Methodology for the estimates of the determinants of Happiness?*. The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00235.x

Fuchs, T., & Woessmann, L. (2007). What accounts for international differences in student performance? A re-examination using PISA data. Empirical Economics, 32(2), 433–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-006-0087-0

Gallie, D. (2007). Employment Regimes and the Quality of Work. Oxford University Press.

Gielen, A. C., & van Ours, J. C. (2014). Unhappiness and job finding. Economica, 81(323), 544–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12089

Green, F. (2011). Unpacking the misery multiplier: How employability modifies the impacts of unemployment and job insecurity on life satisfaction and mental health. Journal of Health Economics, 30(2), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.12.005

Gunderson, M., & Oreopolous, P. (2020). Chapter 3 - Returns to education in developed countries. In S. Bradley & C. Green (Eds.), The Economics of Education (Second Edition) (pp. 39–51). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815391-8.00003-3

Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of Capitalism. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0199247757.001.0001/acprof-9780199247752

Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2010). The Economics of international differences in educational achievement (No. 15949). NBER Working Papers. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/15949.html. Accessed 17 March 2020

Hipp, L. (2016). Insecure times? Workers’ perceived job and labor market security in 23 OECD countries. Social Science Research, 60, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.04.004

Högberg, B., Voßemer, J., Gebel, M., & Strandh, M. (2019). Unemployment, well-being, and the moderating role of education policies: A multilevel study. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 60(4), 269–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715219874386

Horn, D. (2009). Age of selection counts: A cross-country analysis of educational institutions. Educational Research and Evaluation, 15(4), 343–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803610903087011

Ilmakunnas, & Böckerman. (2006). Elusive effects of unemployment on happiness. Social Indicators Research, 79(1), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-4609-5

Jahoda, M. (1982). Employment and unemployment: A social-psycho logical analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Kassenboehmer, S. C., & Haisken-DeNew, J. P. (2009). You’re fired! the causal negative effect of entry unemployment on life satisfaction*. The Economic Journal, 119(536), 448–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02246.x

Levels, M., van der Velden, R., & Stasio, V. D. (2014). From school to fitting work How education-to-job matching of European school leavers is related to educational system characteristics. Acta Sociologica, 57(4), 341–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699314552807

Lucas, R. E. B. (1977). Hedonic wage equations and psychic wages in the returns to schooling. The American Economic Review, 67(4), 549–558.

Marcus, J. (2013). The effect of unemployment on the mental health of spouses – Evidence from plant closures in Germany. Journal of Health Economics, 32(3), 546–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.02.004

Mavridis, D. (2015). The unhappily unemployed return to work faster. IZA Journal of Labor Economics, 4(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40172-014-0015-z

Mavromaras, K., McGuinness, S., O’Leary, N., Sloane, P., & Wei, Z. (2013). Job mismatches and labour market outcomes: Panel evidence on university graduates. Economic Record, 89(286), 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4932.12054

Moulton, B. (1986). Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates. Journal of Econometrics, 32(3), 385–397.

O’Reilly, J., Eichhorst, W., Gábos, A., Hadjivassiliou, K., Lain, D., Leschke, J., et al. (2015). Five characteristics of youth unemployment in Europe: flexibility, education, migration, family legacies, and EU policy. SAGE Open, 5(1), 2158244015574962. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015574962

OECD. (2010). PISA 2009 results: What makes a school successful? (Vol. 4). OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2020a). Indicators of employment protection [access: 15.10.2020a], http://oecd.org/employment/protection

OECD. (2020b). Education at a glance statistics [access: 15.10.2020b], https://stats.oecd.org/

Oreopoulos, P., & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Priceless: The nonpecuniary benefits of schooling. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(1), 159–184. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.25.1.159

Oswald, A. J., Proto, E., & Sgroi, D. (2015). Happiness and productivity. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(4), 789–822. https://doi.org/10.1086/681096

Pastore, F. (2015). The youth experience gap. Explaining national differences in the school-to-work transition. Springer.

Pohl, A., & Walther, A. (2007). Activating the disadvantaged. Variations in addressing youth transitions across Europe. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 26(5), 533–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370701559631

Raffe, D. (2008). The concept of transition system. Journal of Education and Work, 21(4), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080802360952

Raffe, D. (2014). Explaining national differences in education-work transitions. European Societies, 16(2), 175–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2013.821619

Roex, K. L. A., & Rözer, J. J. (2018). The social norm to work and the well-being of the short- and long-term unemployed. Social Indicators Research, 139(3), 1037–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1723-0

Scandurra, R., Cefalo, R., & Kazepov, Y. (2021a). School to work outcomes during the Great Recession, is the regional scale relevant for young people’s life chances? Journal of Youth Studies, 24(4), 441–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2020.1742299

Scandurra, R., Cefalo, R., & Kazepov, Y. (2021b). Drivers of youth labour market integration across European regions. Social Indicators Research, 154(3), 835–856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02549-8

Scherer, S. (2005). Patterns of labour market entry – long wait or career instability? An empirical comparison of Italy, Great Britain and West Germany. European Sociological Review, 21(5), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci029.

Schmidt-Catran, A. W., & Fairbrother, M. (2016). The random effects in multilevel models: Getting them wrong and getting them right. European Sociological Review, 32(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv090

Shavit, Y., & Muller, W. (2000). Vocational secondary education. European Societies, 2(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/146166900360710

Slag, M., Burger, M. J., & Veenhoven, R. (2019). Did the Easterlin Paradox apply in South Korea between 1980 and 2015? A case study. International Review of Economics, 66(4), 325–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-019-00325-w

Stam, K., Sieben, I., Verbakel, E., & de Graaf, P. M. (2016). Employment status and subjective well-being: The role of the social norm to work. Work, Employment & Society, 30(2), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017014564602

Stavrova, O., Schlösser, T., & Fetchenhauer, D. (2011). Are the unemployed equally unhappy all around the world? The role of the social norms to work and welfare state provision in 28 OECD countries. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(1), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2010.11.002

Stegmueller, D. (2013). How many countries for multilevel modeling? A comparison of frequentist and Bayesian approaches. American Journal of Political Science, 57(3), 748–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12001

Stutzer, A., & Lalive, R. (2004). The role of social work norms in job searching and subjective well-being. Journal of the European Economic Association, 2(4), 696–719. https://doi.org/10.1162/1542476041423331

Tamesberger, D. (2017). Can welfare and labour market regimes explain cross-country differences in the unemployment of young people? International Labour Review, 156(3–4), 443–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12040

van der Meer, P. H. (2014). Gender, unemployment and subjective well-being: why being unemployed is worse for men than for women. Social Indicators Research, 115(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0207-5

Viñas-Bardolet, C., Guillen-Royo, M., & Torrent-Sellens, J. (2020). Job characteristics and life satisfaction in the EU: A domains-of-life approach. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(4), 1069–1098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09720-5

Vossemer, J., Gebel, M., Täht, K., Unt, M., Högberg, B., & Strandh, M. (2017). The effects of unemployment and insecure jobs on well-being and health: The moderating role of labor market policies. Social Indicators Research, 138(3), 1229–1257.

Walther, A. (2006). Regimes of youth transitions choice, flexibility and security in young people’s experiences across different European contexts. Young, 14(2), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308806062737

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (1998). Why are the unemployed so unhappy?Evidence from Panel data. Economica, 65(257), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0335.00111

Woessmann, L. (2016). the importance of school systems: Evidence from international differences in student achievement. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.3.3

Wolbers, M. H. J. (2003). Job mismatches and their labour-market effects among school-leavers in Europe. European Sociological Review, 19(3), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/19.3.249

Wolbers, M. H. J. (2007). Patterns of labour market entry a comparative perspective on school-to-work transitions in 11 European countries. Acta Sociologica, 50(3), 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699307080924

World Bank. (2020). World Bank open data, [access: 15.10.2020], https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD

Wu, C.-H., Luksyte, A., & Parker, S. K. (2015). Overqualification and subjective well-being at work: The moderating role of job autonomy and culture. Social Indicators Research, 121(3), 917–937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0662-2

Wulfgramm, M. (2014). Life satisfaction effects of unemployment in Europe: The moderating influence of labour market policy. Journal of European Social Policy, 24(3), 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928714525817

WVS. (2015). World value survey 1981–2014 official aggregate (Vol. 20150418). World Values Survey Association.

Zhu, R., & Chen, L. (2016). Overeducation overskilling and mental well-being. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejeap-2015-0187

Funding

The study presented in the article was financially supported through the National Science Centre (Narodowe Centrum Nauki) grant 2018/30/M/HS4/00744.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I am the sole author with 100% contribution.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Compliance with ethical standards

Not applicable. The analysis uses anonymized, publicly available data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Buttler, D. Employment Status and Well-Being Among Young Individuals. Why Do We Observe Cross-Country Differences?. Soc Indic Res 164, 409–437 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02953-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02953-2