Abstract

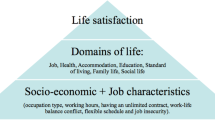

Cross-national comparisons generally show large differences in life satisfaction of individuals within and between European countries. This paper addresses the question of whether and how job quality and working conditions contribute to the quality of life of employed populations in nine strategically selected EU countries: Finland, Sweden, the UK, the Netherlands, Germany, Portugal, Spain, Hungary, and Bulgaria. Using data from the European Quality of Life Survey 2003, we examine relationships between working conditions and satisfaction with life, as well as whether spillover or segmentation mechanisms better explain the link between work domain and overall life satisfaction. Results show that the level of life satisfaction varies significantly across countries, with higher quality of life in more affluent societies. However, the impact of working conditions on life satisfaction is stronger in Southern and Eastern European countries. Our study suggests that the issue of security, such as security of employment and pay which provides economic security, is the key element that in a straightforward manner affects people’s quality of life. Other working conditions, such as autonomy at work, good career prospects and an interesting job seem to translate into high job satisfaction, which in turn increases life satisfaction indirectly. In general, bad-quality jobs tend to be more ‘effective’ in worsening workers’ perception of their life conditions than good jobs are in improving their quality of life. We discuss the differences in job-related determinants of life satisfaction between the countries and consider theoretical and practical implications of these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Davoine et al. (2008), however, contend that because of lack of political consensus the indicators exclude some fundamental dimensions of employment quality, such as wages. Also, Green (2006) points at deficiencies in the European definition in neglecting dimensions such as wages and work intensity.

The methodological question of whether such a ten-point scale can be used as a cardinal variable in an OLS regression has been addressed by Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004) in a study on happiness scores. They assert that assuming ordinality (as usually done by economists) or cardinality of happiness scores makes little difference for the results.

A potential problem with measuring working conditions is the reliance on self-reported attitudinal data that may have several biases. One such bias is habituation, where respondents get used to bad jobs, for example, and stop reporting their working conditions as poor. However, there are no other standardized methods of assessing job quality other than using surveys to ask workers about their jobs. With such caveats in mind, we nevertheless adhere to the view that subjective reports are valid and reasonably credible (see also Fahey and Smyth 2004).

The highest GDP per capita can be found in The Netherlands (€26,020), followed by Finland (€24,280), Germany (€24,140), the United Kingdom (€23,160), Sweden (€23,130), Spain (€19,100), Portugal (€16,920), Hungary (€12,300), and Bulgaria (€5,700).

For example, Dutch respondents were randomly assigned GDP per capita values ranging between €25,760 (Dutch GDP − 1%) and €26,280 (Dutch GDP + 1%).

Differences in the meaning and implications of the work-family conflict is perhaps at the core of the problem of transferring successful measures for improving the work-life balance from some countries to others (Leitner and Wroblewski 2006).

References

Allardt, E. (1976). Dimensions of welfare in a comparative Scandinavian study. Acta Sociologica, 19, 227–239.

Allardt, E. (1993). Having, loving, being: An alternative to the Swedish model of welfare research. In M. C. Nussbaum & A. Sen (Eds.), The quality of life (pp. 88–94). Oxford: Clarendon.

Anxo, D., & Boulin, J.-Y. (2006). The organization of time over the life course. European trends. European Societies, 8, 319–341.

Aycan, Z., & Eskin, Z. (2005). Relative contribution of childcare, spousal, and organizational support in reducing work-family conflict for males and females. The case of Turkey. Sex Roles, 53, 453–471.

Bedeian, A. G., Burke, B. G., & Moffett, R. G. (1988). Outcomes of work-family conflict among married male and female professionals. Journal of Management, 14, 475–491.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being u-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science and Medicine, 66, 1733–1749.

Böhnke, P. (2008). Does society matter? Life satisfaction in the enlarged Europe. Social Indicators Research, 87, 189–210.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multi-dimensional measure of work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56, 249–267.

Clark, A. (2001). What really matters in a job? Hedonic measurement using quit data. Labor Economics, 8, 223–242.

Clark, A. (2005). What makes a good job? Evidence from OECD countries. In S. Bazen, C. Lucifora, & W. Salverda (Eds.), Job quality and employer behavior (pp. 11–30). Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cummins, R. A. (1996). The domains of life satisfaction: An attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research, 38, 303–328.

Davoine, L., Erhel, C., & Guergoat-Lariviere, M. (2008). Monitoring quality in work: European employment strategy indicators and beyond. International Labour Review, 147, 164–198.

Delhey, J. (2004). Life satisfaction in the enlarged Europe. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 25, 276–302.

EQLS. (2003). European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions and Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. European Quality of Life Survey, 2003 [computer file]. (Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], February 2006. SN: 5260).

Erikson, R. (1974). Welfare as a planning goal. Acta Sociologica, 17, 273–288.

Erikson, R. (1993). Descriptions of inequality: The Swedish approach to welfare research. In M. C. Nussbaum & A. Sen (Eds.), The quality of life (pp. 67–87). Oxford: Clarendon.

European Commission. (2001). Employment and social policies: A framework for investing in quality. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

Fahey, T., & Smyth, E. (2004). Do subjective indicators measure welfare? Evidence from 33 European societies. European Societies, 6, 5–27.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Frone, M. R. (2003). Work-family balance. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 143–163). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Prevalence of work-family conflict. Are work and family boundaries asymmetrically permeable? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 723–729.

Frone, M. R., Yardley, J. K., & Markel, K. S. (1997). Developing and testing an integrative model of the work–family interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50, 145–167.

Gallie, D. (2002). The quality of working life in welfare strategy. In G. Esping-Andersen, D. Gallie, A. Hemerijck, & J. Myles (Eds.), Why we need a new welfare state (pp. 96–127). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gallie, D. (2007). Production regimes, employment regimes, and the quality of work. In D. Gallie (Ed.), Employment regimes and the quality of work (pp. 1–33). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gash, V., Mertens, A., & Gordo, L. R. (2007). Are fixed-term jobs bad for your health? A comparison of West Germany and Spain. European Societies, 9, 429–458.

Goode, W. J. (1960). A theory of role strain. American Sociological Review, 25, 483–496.

Green, F. (2006). Demanding work. The paradox of job quality in the affluent economy. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10, 76–88.

Haller, M., & Hadler, M. (2006). How social relations and structures can produce happiness and unhappiness: An international comparative analysis. Social Indicators Research, 75, 169–216.

ILO (1999). Decent work. (Report of the Director-General to the 87th Session of the International Labour Conference, Geneva).

Kalleberg, A. L. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers. Employment relations in Transition. American Sociological Review, 74, 1–22.

Lambert, S. J. (1990). Processes linking work and family: A critical review and research agenda. Human Relations, 43, 239–257.

Lance, C. E., Mallard, A. G., & Michalos, A. C. (1995). Tests of the causal directions of global–life facet satisfaction relationships. Social Indicators Research, 34, 69–92.

Leitner, A., & Wroblewski, A. (2006). Welfare states and work–life balance. Can good practices be transferred from the Nordic countries to conservative welfare states? European Societies, 8, 295–317.

Noll, H.-H. (2004). Social indicators and quality of life research: Background, achievements, and current trends. In N. Genov (Ed.), Advances in sociological knowledge over half a century (pp. 151–181). Wiesbaden: VS.

Oswald, A. J., & Wu, S. (2010). Objective confirmation of subjective measures of human well-being. Evidence from the USA. Science, doi:10.1126/science.1180606.

Pichler, F., & Wallace, C. (2009). What are the reasons for differences in job satisfaction across Europe? Individual, compositional, and institutional explanations. European Sociological Review, 25, 535–549.

Pleck, J. H. (1977). The work-family role system. Social Problems, 24, 417–427.

Präg, P., Guerreiro, M. d. D., Nätti, J., & Brookes, M. (2010a). Quality of work and quality of life of service sector workers. Cross-national variations in eight European countries. In M. Bäck-Wiklund, T. van der Lippe, L. den Dulk, & A. van Doorne-Huiskes (Eds.), Quality of work and life. Theory, practice, and policy. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan (forthcoming).

Präg, P., Mau, S., & Verwiebe, R. (2010b). Quality of life. In S. Mau & R. Verwiebe, European societies. Mapping structure and change. Bristol: Policy Press.

Rode, J. C., & Near, J. P. (2005). Spillover between work attitudes and overall life attitudes. Myth or reality? Social Indicators Research, 70, 79–109.

Royuela, V., López-Tamayo, J., & Suriñach, J. (2008). The institutional vs. the academic definition of the quality of work life: What is the focus of the European commission? Social Indicators Research, 86, 401–415.

Sirgy, J. (2002). The psychology of quality of life. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Sirgy, M. J., Efraty, D., Siegel, P., & Lee, D.-J. (2001). A new measure of quality of work life (QWL) based on need satisfaction and spillover theories. Social Indicators Research, 55, 241–302.

Staines, G. (1980). Spillover versus compensation: A review of the literature on the relationship between work and nonwork. Human Relations, 33, 111–129.

Szücs, S., Drobnič, S., den Dulk, L., & Verwiebe, R. (2010). Quality of life and satisfaction with work-life balance. In M. Bäck-Wiklund, T. van der Lippe, L. den Dulk, & A. van Doorne-Huiskes (Eds.), Quality of work and life. Theory, practice, and policy. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan (forthcoming).

van Praag, B. M. S., Frijters, P., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2003). The anatomy of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51, 29–49.

Veenhoven, R. (1996). Developments in satisfaction research. Social Indicators Research, 37, 1–46.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). The four qualities of life. Ordering concepts and measures of the good life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 1–39.

Verbakel, E., & DiPrete, T. (2008). The value of non-work time in cross-national quality of life comparisons: The case of the United States vs. the Netherlands. Social Forces, 87, 679–712.

Wallace, C., Pichler, F., & Hayes, B. (2007). First European quality of life survey. Quality of work and life satisfaction. Luxembourg: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Wilensky, H. (1960). Work, careers, and social integration. International Social Science Journal, 12, 543–560.

Zapf, W. (1984). Individuelle Wohlfahrt. Lebensbedingungen und wahrgenommene Lebensqualität [Individual welfare. Living conditions and perceived quality of life]. In W. Glatzer & W. Zapf (Eds.), Lebensqualität in der Bundesrepublik [Quality of life in the Federal Republic of Germany] (pp. 13–26). Frankfurt a. M. and New York: Campus.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported in part by the European Commission Sixth Framework Programme Project “Quality of Life in a Changing Europe” (QUALITY), and the Network of Excellence “Reconciling Work and Welfare in Europe” (RECWOWE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Drobnič, S., Beham, B. & Präg, P. Good Job, Good Life? Working Conditions and Quality of Life in Europe. Soc Indic Res 99, 205–225 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9586-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9586-7