Abstract

Prior to the February 2019 announcement that the Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) will be used to estimate household food insecurity, there has not been a standardised measurement approach used in the United Kingdom (UK). Measurement has instead been somewhat inconsistent, and various indicators have been included in national and regional surveys. There remains a gap relating to the comparative usefulness of current and past food insecurity measures used in Northern Ireland (NI) (HFSSM; European Union-Survey of Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) food deprivation questions), and the potential usefulness of a headline indicator similar to that used to measure fuel poverty. This study presents findings from Northern Ireland (NI) stakeholder interviews (n = 19), which examined their perspectives on food insecurity measures which have previously been or are currently, or could potentially, be used in the UK/NI (HFSSM; EU-SILC food deprivation questions; headline indicator). Interview transcripts were coded using QSR NVivo (v.12) and inductively analysed to identify relevant themes. Stakeholders preferred the HFSSM to the EU-SILC, reasoning that it is more relevant to the food insecurity experience. A headline indicator for food insecurity was considered useful by some; however, there was consensus that it would not fully encapsulate the food insecurity experience, particularly the social exclusion element, and that it would be a complex measure to construct, with a high degree of error. This research endorses the use of the HFSSM to measure food insecurity in the UK, and provides recommendations for consideration of any future modification of the HFSSM or EU-SILC measurement instruments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Food insecurity has been defined as “the inability to acquire or consume an adequate quality or sufficient quantity of food in socially acceptable ways, or the uncertainty that one will be able to do so” (Radimer et al., 1992, p. 39). To date various indicators have been used to approximate food insecurity in both developing and developed countries (Beacom et al., 2020). Food insecurity has been measured annually in the US since 1995 (Rafiei et al., 2009) and in Canada since 2004 (Tarasuk, 2016) using standardised indicators. However, in the UK, there had been no established government-endorsed indicator of food insecurity which was consistently used across all regions (Smith et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2018), until the recent announcement that food insecurity would begin to be measured across all four regions of the UK from April 2019 (Butler, 2019), using the 10-item version of the United States Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM). Prior to this, England, Wales, Scotland and NI have included food insecurity measurement questions in their respective household surveys, but there has been variation in the measures and questions which have been selected by each, therefore making it difficult to accurately monitor food insecurity comparably across time and across locations throughout the UK. Although comparative data across regions are not yet available, current findings indicate food insecurity is a problem in the UK. Recent survey (Food and You—Wave Five) data found that 10% of adults living in England, Wales and NI are food insecure (as measured using the 10-item version of the HFSSM), having experienced inadequate access to food due to a lack of money (Fuller et al., 2019). A further 10% of respondents were found to be only marginally food secure using this measurement approach (Fuller et al., 2019), meaning that although not categorised as food insecure, they answered affirmatively to some questions, such as worry related to accessing adequate food, experiencing having inadequate food, and some occurrence of being unable to afford balanced meals. In NI specifically, the most recently published results from the Health Survey for Northern Ireland in 2018/19 (using questions on food deprivation from the European Union-Survey of Income and Living Conditions) found that 4% of households reported that there had been at least 1 day when they had not eaten a substantial meal in the last fortnight due to a lack of money (Department of Health, 2021). Comparison of food insecurity prevalence across locations and across time periods is difficult when different indicators are used. This study qualitatively investigates relevant stakeholder’s opinions on two indicators currently used in NI (and also used elsewhere in the UK), as well as investigating perspectives on the feasibility of a novel measurement approach (headline indicator), similar to how fuel poverty is currently measured in NI. The following literature review presents an overview of the implications of food insecurity, justifying the need for a consistent indicator; an overview of past, present and potential approaches to measuring food insecurity in NI; and presents theoretical underpinning for measurement of social indicators such as food insecurity. Methods are then outlined, followed by a thematic presentation of study findings, discussion of findings, and conclusions.

2 Literature Review

Living in food insecurity not only impacts on dietary intake, and related physical health, but can also impact on mental health, and can leave people and families socially excluded (Grimaccia & Naccarato, 2020; Martinez et al., 2020; O’Connell et al., 2019). Furthermore, physical and mental implications of the food insecurity experience (i.e. hunger, lack of energy, anxiety) can result in diminished effectiveness in work and education (Martinez et al., 2020). Measuring food insecurity and investigating the demographics of those who experience it can help identify vulnerable groups in order that policy attention can be focused towards tackling contributors where possible (Palmeira et al., 2019).

UK policy is currently uninformed due to the lack of comparable data on those experiencing food insecurity and on the population-level factors which make people more susceptible to food insecurity (Smith et al., 2018). Collecting quantitative data using a standard measure across the UK will allow for monitoring of changes over time and across locations, and can aid assessment of policy implications and help policy development in order to develop more focused strategies and targeted interventions to tackle diet-related health inequalities in society (End Hunger, 2019; O’Connell et al., 2019; Palmeira et al., 2019; Sharpe, 2016). Therefore, it is important that informed decisions are made to choose the most appropriate measure.

Since 2012 food security questions have been included in the NI Health Survey, and both the EU-SILC food deprivation questions and the HFSSM have been used. The EU-SILC is a survey developed to monitor deprivation and social exclusion across countries in the European Union (Alkire et al., 2014; Arora et al., 2015) and carries four questions pertaining to food insecurity (Table 1) which have been adopted in the NI Health Survey since 2012 (Department of Health, 2019).

The HFSSM (Table 2) consists of eighteen questions (in households with children), or ten questions (in households without children) which assess the degree of food security experienced by households over the past 12 months (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2015; Kharisma & Abe, 2020). A six-item version of the HFSSM has also been used, as have other shorter adaptations or modifications of the module, e.g. adaptations for different cultures, modification of the recall period, or rapid approaches to measurement using just two of the HFSSM questions (Beacom et al., 2020; Knowles et al., 2016).

The annual NI Health Survey included HFSSM questions from 2012 to 2016 (Department of Health, 2019). In 2016, the Food Standards Agency ‘Food and You’ survey administered in England, Wales and NI began collecting data on food security using the ten-item adult HFSSM, and in February 2019 it was announced that the ten-item HFSSM would be included in the UK Department for Work and Pension’s annual Family Resources Survey.

Since food insecurity questions were first introduced to the NI Health Survey in 2012, use of these questions has been inconsistent. There have been variations each year in which questions from the HFSSM are chosen (Department of Health, 2019), and furthermore, since 2016 HFSSM questions have been removed entirely and EU-SILC questions are instead the sole measure used (Table 3).

Although NI stakeholders have highlighted the need for a consistent food insecurity measurement approach (King et al., 2015), there is currently no published qualitative literature regarding the opinions of stakeholders as to the appropriateness of existing measures (EU-SILC and HFSSM) for use in a UK/NI context, or whether a headline indicator similar to the fuel poverty measurement would be a useful alternative. A headline indicator can be defined as a quantifiable measurement approach or monitoring tool which can be used to track progress towards strategic targets (e.g. health system performance or policy impacts) and to facilitate comparisons across areas and time periods (Perić et al., 2018). Fuel poverty in NI has an identified and widely-used indicator, with households indicated to be experiencing fuel poverty if they spend more than 10% of household income on heating the home (DECC, 2019). Therefore, there is potential to explore if a similar headline indicator approach which examines food expenditure as a percentage of household income can be used to indicate food insecurity.

2.1 Theoretical Underpinning

Social indicators, such as food insecurity levels, can be measured using either an objective or subjective approach (Townsend, 1979). An objective approach, which dates back to social research in the nineteenth century, focuses on measuring observable factors such as income (Mahmood et al., 2019; Veenhoven, 2002). Conversely a subjective approach, which gained prominence in the 1960s stemming from survey research, considers perceptions and feelings related to the phenomenon such as satisfaction with income (Veenhoven, 2002). The literature notes a shift in perception and measurement of food insecurity through objective indicators to subjective perceptions (Mahmood et al., 2019; Maxwell, 1996; Webb et al., 2006). The subjective viewpoint that one does not have enough to get along can be classified as either absolute (i.e. less than an objectively defined, absolute minimum) or relative (i.e. having less than others), or somewhere in between (Hagenaars & de Vos, 1988). Webb et al (2006) discuss how conceptually, subjective or experiential assessments of food insecurity aim to capture expressions of how people experience hunger and food insecurity, expressions which are often captured using qualitative data collection methods such as interviews or focus groups with those experiencing food insecurity (Crawford et al., 2014; Purdy et al., 2007; Radimer et al., 1990). Garnering information this way means experience is more likely to be culturally and personally relevant and reflective of their actual experience, rather than of others’ perceptions of it (Grimaccia & Naccarato, 2019; Webb et al., 2006). These three aforementioned categorisations of how food insecurity can be defined and measured (objective/absolute, relative, subjective) will each result in different estimates of the determinants/predictors of food insecurity, and the extent to which it exists (Hagenaars & de Vos, 1988). The food insecurity measurement modules discussed in this paper (EU-SILC food deprivation questions, HFSSM) combine objective and subjective questions, while the headline indicator approach adopts a relative perspective. This study aims to address the gap in the literature regarding stakeholder’s opinions on subjective/objective food insecurity measurement modules currently used in NI/the UK, and on the feasibility of an alternative objective headline indicator food insecurity measurement approach.

3 Methods

3.1 Data Collection

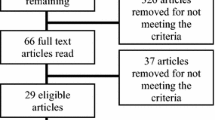

Data were collected through interviews with a diverse purposive sample of stakeholders (n = 19). This study was part of a larger research study, which used a semi-structured interview topic guide consisting of six main topics related to food insecurity, of which one was measurement. The interview topic guide excerpt relating to measurement is available as an appendix (“Appendix 1”). Prior to constructing the interview topic guide, the researcher had read both the related academic and grey literature (e.g. media publications, government reports), and met with two stakeholders (a non-governmental organisation representative and a public health representative) to discuss some of the issues around the topic, which helped to form the interview topic guide themes and questions. During these preliminary discussions with stakeholders, and during consultation of grey literature produced in the UK, it was realised that the term ‘food poverty’ is more commonly used in practitioner settings in the UK than the term ‘food insecurity’ when referring to the state of being unable or uncertain about one’s ability to acquire sufficient food in socially acceptable ways [as per the earlier introduced definition by Radimer et al. (1992)]. Although it is acknowledged by the research team and considered in the literature that there are nuances between both terms (Beacom et al., 2021; O’Connor et al., 2016), in this instance it was decided that for purposes of clarity and understandability, the term ‘food poverty’ would be the nomenclature used during stakeholder interviews, as synonymous with food insecurity.

3.2 Participants

Before selecting a sample of participants to invite to interview it was important to consider whose perspectives would be most useful and appropriate considering the interview topic guide and focus of the research. As it was important to get a variety of perspectives, a range of stakeholders (e.g. policy makers, political representatives, practitioners, campaigners, consumer sub-group representatives, community workers and academics) were invited to interview. Stakeholder relevance was determined by criteria that they either work in or have an interest in the area of food insecurity, or work closely with or on behalf of consumer groups, some of whom may experience food insecurity. As the larger project focused on food insecurity in NI, only stakeholders from NI were recruited as participants. Recruitment was not limited to a specific region in NI, and the eventual sample included participants from three of the six counties in NI. Some of the participants were previously known to the research team, and some had agreed to an interview prior to being sent an email with further information. Others were unknown to the research team but were contacted via email, using their publicly available contact details, or following introduction by a mutual contact, in order to increase the variety of groups represented in the sample. Of the 30 suitable participants identified and contacted, 19 of these correspondences proceeded to interview. Participants were contacted on an ongoing basis between October 2017–May 2018 and interviews continued until it was believed an appropriate number of groups had been represented and data saturation had been reached.

3.3 Data Analysis

An inductive thematic analysis process was used for data analysis, following the six-stage process for qualitative data analysis recommended by Braun and Clarke (2006). The first stage in data analysis involved familiarisation with the data through transcribing all interviews, cleaning the data, and then reading and re-reading transcripts before beginning the analysis process in order to achieve data immersion. Transcripts were first and second level coded in hard copy to generate initial codes and deduct meaning (Miles et al., 2013; Saldana, 2015), and a codebook was developed containing predetermined codes related to the interview topic guide and research objectives. Transcripts were uploaded to the qualitative analysis software NVivo 12 and coded according to predetermined and emerging codes. Codes were then examined to find common themes, and four main preliminary themes were identified. Following theme searching/identification, Braun and Clarke (2006) recommend reviewing of themes, therefore transcripts were again re-read and an overview of three to five themes or main points emerging from each interview were noted. The ‘themes’ of each individual transcript were then compiled and considered in order to group common themes for the entire dataset. The purpose of this was to check if the preliminary themes emanating from the identified codes were similar to the themes coming from the transcripts. This confirmed that the themes emanating from the codes were the same themes/main points from each interview. Themes were then defined and named (Braun & Clarke, 2006), and codes were grouped into subthemes, with a total of two subthemes identified within each theme.

4 Results

One of the four themes emanating from the overarching research was the ‘Need to raise awareness and provide evidence’, with the corresponding subthemes of ‘Defining food insecurity’ and ‘Measuring food insecurity’. The following results which address the aim of this study are therefore extracted from the subtheme ‘Measuring food insecurity’, and are presented according to stakeholders’ opinions on (i) the EU-SILC food deprivation measures, (ii) the HFSSM, and (iii) the feasibility of a headline indicator. Where there was clear similarity of opinion among stakeholders, findings are presented alongside numerical indication as to the strength of opinion among participants.

4.1 Opinions on the EU-SILC Food Deprivation Measures

Several participants (n = 9) felt that the EU-SILC measures needed updating as they considered certain questions to be no longer culturally relevant:

It just maybe needs a bit of a 2017 reality check on it. (Participant 18, Consumer organisation)

Question two, “does your household have a roast joint once a week”, was believed to be particularly dated as stakeholders felt this was something that may no longer be custom and practice in familial homes. This may be because of change in lifestyle, such as the rise of one person and dual person households, as well as general changes in diets, as large multi-national retailers and globalisation have allowed for a greater range of food options to be available:

I think there’s probably less people having a roast dinner on Sunday than there was 20 years ago because there’s just different things and different lifestyles, more different options [of food]. (Participant 4, Consumer representative)

One stakeholder stated the opinion that questions regarding consumption of meat (or vegetarian equivalent) are of no benefit as it is paramount to simply asking a question regarding income/food spend:

Does your household have a joint? All you’re really saying is ‘that’s an expensive thing, how often do you have it?’ So you might as well say ‘how much do you spend on food a week?’ (Participant 6, Campaigning organisation)

However, they also questioned the appropriateness of asking about ‘vegetarian alternative’ consumption as equivalent to meat, as these two categories of products may be different from an affordability perspective:

it seems to be all about affordability and I suppose… the vegetarian equivalent sort of throws me a bit because meat generally is more expensive, but maybe they’re talking about Quorn and things which are more expensive because they’re processed (Participant 6, Campaigning organisation)

Similarly, another stakeholder (Participant 11, Local council) was of the view that the EU-SILC food deprivation questions shown are more concerned with the quality rather than the quantity of foods consumed.

One participant considered the equipment that would be required to cook the foods specified in question one and two, commenting that some of those in food poverty may not even have an oven in which to cook the roast:

If you don’t have a cooker to cook your roast joint in… I’ve heard of people heating food on the radiator because they have no cooker. (Participant 5, Consumer representative)

Other participants (n = 5) from a variety of backgrounds (consumer representative, food bank practitioner, local council representative, political councillor, academic) made similar comments regarding equipment. One (Participant 19, Political Counsellor) stated that in their experience people sometimes didn’t have the equipment necessary to cook food (e.g. pots and pans), while a food bank practitioner (Participant 17) discussed how even if people have the necessary equipment and are given food (e.g. from food banks), they may not have electricity or gas to fuel their cooker or microwave to cook it.

Some also believed that similarly to question two, question four “Does the household have family or friends for a drink or a meal once a month?” may also be outdated. This may be because it is perhaps more common now to eat out, as well as increasing globalisation (e.g. moving away for work) resulting in people living apart from family and friends and therefore being less likely to socialise inside the home.

One participant was of the opinion that question three, “During the last fortnight was there ever a day (i.e. from getting up to going to bed) when you did not have a substantial meal due to lack of money”, was the EU-SILC question most likely to make an impact and capture the attention of the public, the media and policy makers. This is because it was considered more hard-hitting than the others:

Whilst I get why these questions are there [EU-SILC questions 1, 2 and 4] there is only one of these [EU-SILC Q3] which would make any traction. (Participant 1, Public Health)

… I think if you took those out in a straw poll to the man or woman on the street… Hypothetically speaking, if you put figures around this like 25,000 households in Northern Ireland are not able to have meat every [day] ... [and asked them] what do you think? They would probably think ‘ok, that’s a bit unfortunate but so what?’ 30,000 aren’t able to have roast, what do you think of that? 25,000 aren’t able to have friends and family, well that one there is maybe a wee bit more hard hitting, but that one - 25,000 at least once in fortnight go without food - is the one that would grab their attention more than any others, and politically it is just the same. (Participant 1, Public Health)

When stakeholders were asked to consider if there was anything they thought the EU-SILC module of questions is lacking, some participants suggested that a reference to cooking skills, and/or a reference to whether or not meals were cooked from scratch would be a useful addition. The point was made by some that meals with meat, chicken and fish (as per question one) are available at McDonald’s, or they could be ready meals; therefore just because consumers are eating from this food group does not necessarily mean they are acquiring food from healthy sources. It was also noted that as there was a mention of meat in questions one and two, it was surprising there was no likewise mention of fruit and vegetables. These suggestions imply that some stakeholders were implying the ‘adequate quality’ terminology in Radimer et al.’s (1992) definition to refer to adequate quality nutritionally. In terms of questions which would be a potentially useful addition, it was thought that a more explicit mention of, or question about, skipping meals would be useful as it represents the certain indication that people are in food poverty. Additionally, one suggested the inclusion of a question addressing the anxiety related to the uncertainty of not knowing where your next meal will come from, thereby addressing the uncertainty element of the definition of food insecurity they were provided with:

There could be something there about anxiety…. So do you ever worry about providing for your family or whatever, and something about mental health. (Participant 13, Food redistribution organisation)

There was also consideration that the questions may not be specific enough to ascertain whether the food eaten was nutritious or not:

See that every second day: that could be pre-heated meals which doesn’t have the same nutritional value. (Participant 13, Food redistribution organisation)

Although the comment was made that it needed to be a quantifiable indicator to get attention, others were however adamant that the social inclusion aspect was important:

What I especially love is the fourth question, which other stakeholders might well downplay, because I think the social exclusion issue shouldn’t be underestimated. (Participant 16, Academic)

Although the brevity of the module was considered positive by some: “this one is short and to the point” (Participant 8, Social Policy), others considered the measures too brief to capture the food poverty experience accurately: “I don’t think four measures are enough” (Participant 19, Political Councillor).

4.2 Opinions on the HFSSM

The feedback on the HFSSM was mostly positive (n = 15): “very comprehensive” [Participant 7, Health Policy]; “very relevant” (Participant 17, Food bank); and “they’re fairly simple questions; when you first said to me I thought, well, four questions would be better than eighteen but those questions are quite … I can see you would get more out of those.” (Participant 4, Consumer representative).

However, some stakeholders who work with consumers considered the module to be “too long” (Participant 10, Community campaigner) or repetitive:

I think there seems to be a lot of duplication. You really really have to examine the questions to see how is that different from the last. I would say it would probably be quite complicated for them to answer. (Participant 18, Consumer organisation)

There were mixed opinions among stakeholders: one stakeholder (Participant 10, Community campaigner) was of the opinion that “surely this one [question eight] would just answer it all” [Q8—In the last 12 months did you ever lose weight because you didn’t have enough money for food?], while another stated:

I don’t know whether number 8 works really… Whereas, once upon a time, food poverty led to [weight loss], it’s now more likely to lead to obesity. (Participant 18, Consumer organisation)

The likeliness of ambiguity around what certain terms such as ‘a balanced diet’ would mean to different people was considered, therefore reinforcing the need for clarity around terminology to aid understanding:

I would love to ask the people in here ‘describe a balanced meal to me’. What they would describe to me might be different than what I would describe to them. (Participant 17, Food bank)

I suppose the thing that jumps out at me is assuming people know what’s meant by a balanced meal, and that’s open to a lot of interpretation. (Participant 6, Campaigning organisation)

One stakeholder working in the community remarked surprise that there was no explicit mention of, or question on, health considering the link between being food insecure and having health problems:

This is really quite interesting because none of these, ever explicitly talk about health, [and the] link between people suffering from food poverty and the increase in diet related poor health is known in every doctor’s surgery across the province. (Participant 10, Community campaigner)

Overall, views on the HFSSM were generally more positive than those on the EU-SILC measures. Of those stakeholders who cited a preference for one or the other measure (n = 11), the majority (n = 8) preferred the HFSSM to the EU-SILC:

Well, I mean I’m only half way through it, but it’s already a lot better than the first one from the point of view of giving a much more tangible measure of how somebody’s income relates to what food they’re able to buy. (Participant 6, Campaigning organisation)

[The HFSSM] will illicit more information from a person and actually asks, you know, do you worry that food will run out? That’s a big indicator that you’re in food poverty. That’s not addressed in this [EU-SILC]. (Participant 14, Political representative - MLA)

As well as considering the HFSSM to be a superior measure in terms of how it addresses various dimensions of the food poverty experience that stakeholders perceived as important, it was also believed that respondents would prefer the format and content of the HFSSM to the EU-SILC:

I definitely think the way that [the way] this one [HFSSM] is worded would be more appealing for someone to fill in. It’s definitely easier to understand. (Participant 15, Local council)

I think people would respond to that better. (Participant 14, Political representative - MLA)

Other feedback considered that the HFSSM questions were starker and much harder hitting than the EU-SILC so they would be more likely to get media and policy attention:

Well I haven’t read them all, but the first thing that strikes me right away is these [HFSSM] are much starker, harder hitting questions if they were in the public domain. (Participant 1, Public Health)

However, it was suggested that the 12-month reference period of the HFSSM may be more difficult to recollect in comparison with the current and ongoing time frame of the EU-SILC:

Those [EU-SILC] are probably easier to answer… Do you have a roast joint once a week? You could probably say yes or no, whereas these [HFSSM] are probably more, in the last 12 months, probably quite a long [reference period] ... although if you’re living in that situation it probably is daily. (Participant 11, Local council)

Opinions were varied as to which module was easier to answer. One person who worked in the community with participants who were vulnerable to food insecurity considered the way the EU-SILC questions were worded was more difficult to interpret than the HFSSM questions and that this may be off-putting for some:

I’m not sure what information you would really gain from that. Even if I was to go round with these to some of our clients or constituents within our Borough, even the way those are written [EU-SILC] is much more highfalutin than these American ones, and even that could be a barrier. The way that they’re written could put people off and put people on the negative. (Participant 15, Local council)

4.3 Feasibility of a Headline Indicator

Prior to discussing the feasibility of a headline indicator for food poverty, the example of fuel poverty was discussed to ascertain whether participants were aware of the existing fuel poverty measure and to discuss how a similar headline indicator could be used for food poverty.

Although it was acknowledged that due to the multifaceted nature of food poverty it would be difficult to reduce the concept to a headline indicator, there was a general opinion (n = 13) among stakeholders that a headline indicator would be useful:

There needs to be a quantity, a percentage put on it to understand. (Participant 14, Political representative - MLA)

Government really needs a headline figure to be able to initially begin to address and identify those communities that are most at risk. (Participant 9, Academic/Political Councillor)

It was thought by some that a headline indicator would be particularly useful to streamline the setting of targets, and that a resultant simplified figure as to the prevalence of food poverty would help to get policy makers’ attention and catalyse change to improve the situation of those in poverty:

The reason why fuel poverty is streets ahead is because they’ve defined it. It’s very easy: whilst it remains largely unquantified and vague, the politicians don’t have to do anything about it… Until it’s quantified; until there is a figure that can be held up and campaigned upon it is going to be, in my view, very difficult to crack. (Participant 1, Public Health)

I think that, unfortunately, the way that public policy is formulated you have to have measurements and you have to have … you know, there has to be indicators, targets, in order for a resource to be allocated to it. … With the complexities, you’re never going to capture it in its entirety; but at least you have something you can touch and point to, and government can be embarrassed into doing something about it. (Participant 14, Political representative - MLA)

Government need [a measure] they can be held to account over rather than something vague. (Participant 9, Academic/Political Councillor)

Although several stakeholders (n = 13) shared the view that a headline indicator would be useful, particularly in terms of simplicity when communicating statistics about the prevalence of food poverty to the public and government, more than half (n = 11) of stakeholders did not think a headline indicator would be sufficient by itself and that experiential questions are needed to humanise the statistics and win hearts and minds of policy makers.

5 Discussion

When considering the EU-SILC, some stakeholders questioned the appropriateness of questions one and two which enquired about meat (or vegetarian equivalent) consumption, in particular question two which enquired about consumption of a roast joint (or equivalent) and was considered outdated by some participants. Although the EU-SILC questions regarding meat include a caveat of ‘or vegetarian equivalent’, the appropriateness of the focus on meat was questioned with regards to sustainability concerns and current health recommendations. The literature provides some rationale for referencing the ability to afford meat as an indicator of food insecurity, as a study found that in many countries across the EU, many households with children have had to decrease their meat consumption since the 2008 financial crisis for monetary reasons (UNICEF, 2014). Therefore this question can be considered relevant in showing that reduced income can affect nutritional adequacy of diets, and meat/protein sources can be a good indication of this (Husz, 2018). However, as discussed by one stakeholder, it is acknowledged that if the purpose of these questions are to assess respondents ability to afford certain food groups, there may be a disparity between the cost of meat products and meat alternative products. On the other hand, it may be considered that this question is adequately phrased in that respondents will either way indicate whether or not they have been able to consume enough of their chosen product type (meat or meat alternative).

Although some stakeholders felt that the fourth question regarding ability to have friends and family round for a meal/drink may not be as important as the others, and that it may like question two be outdated, Healy (2019) strongly endorses the fourth question, and other scholars emphasise the importance of the social aspect of having the ability to access sufficient, appropriate food (e.g. Caraher & Furey, 2018; O’Connell et al., 2019).

It was suggested that certain questions in the HFSSM and EU-SILC would indicate definitively if the person was food insecure or not, i.e. if people affirmed question eight in the HFSSM that they had lost weight due to lack of money for food, or if they affirmed question three in the EU-SILC that they had gone a full day without a substantial meal due to lack of money for food, that this would be a definitive indicator of food insecurity. This opinion therefore expressed the idea that asking fewer questions, or a single question, referencing severe food insecurity, can replace a long(er) module. However, this approach would potentially exclude those who are marginally/moderately food insecure. Therefore, in order to differentiate between severities, a longer questionnaire with incorporated severity levels is needed (Archer et al., 2017; Bickel et al., 2000). It is acknowledged though that compiling a staged module instrument can be more time consuming and challenging, as it is important to ensure that measures are reliable and valid, and that questions are sensitive and specific (Archer et al., 2017; Bjorney-Urke et al., 2014; Coleman-Jensen, 2009). For example, the design and ordering of the HFSSM questions is very specific and sensitive regarding how the questions capture the food insecurity experience and how the questions increase successively in the severity level of food insecurity they assess (Archer et al., 2017; Rafiei et al., 2009). Although an 18-item module appears long, especially in comparison to the four EU-SILC deprivation questions, the staged nature of the questionnaire means that in practice, the module has been found to take between 1 and 4 min to complete (Sharpe, 2016). Questionnaire length is however an important consideration, as the longer the module the greater the response burden for the respondent, and therefore the greater the risk that participants will not fully complete it, resulting in missing data (Groves et al., 2009). Further, as discussed by one stakeholder, longer questionnaires/measurement modules can be more costly to include in population surveys, which can be a factor influencing choice of indicator.

In comparison with the time frames referenced in EU-SILC questions (every second day, once a week, during the last fortnight, once a month), some stakeholders believed that the 12-month recall period of the HFSSM was too long, or thought that using a shorter time frame of 2 or 3 days would be useful when rapidly assessing if people are currently food insecure. Archer et al (2017) also interviewed stakeholders to assess their opinions on a single item measure with a 12-month recall time frame, and respondents suggested that this time frame was too long and may not provide an accurate estimation of household food security status due to the changes that can occur over a period of 12 months. Illustrating the feasibility of adapting the HFSSM to use a shorter recall time frame, various studies have successfully modified the recall time of the HFSSM from 12 months to 3 months (Ip et al., 2015), and from 12 months to 1 month (Guo et al., 2015; Huet et al., 2017), in order to assess seasonal food security. Modifying existing scales to use a shorter reference time can allow for repeated sampling to identify transient as opposed to long term food insecurity, and can also be useful to examine recall reliability (Huet et al., 2017). These aforementioned studies (Guo et al., 2015; Huet et al., 2017; Ip et al., 2015) have all however examined a specific population (the Canadian Inuit) over a time-bound period. Therefore although this approach has been successful in these study contexts, it is likely not feasible when examining the wider population. As food insecurity measurement modules are usually contained within annual population surveys, a recall time of 12 months is appropriate when examining the food security status of the general population. Further, although alternate indicators, such as dietary diversity and food frequency indicators, require participants to recall food intake from the previous 24 h, as opposed to the longer reference period of 12 months used in experiential indicators such as the HFSSM (Leroy et al., 2015), this shorter reference time can leave more room for error. There are many variables which may affect food consumption on a particular day, therefore a longer timeframe such as the 12-month recall used in the HFSSM may be a more representative, accurate indicator of typical food consumption.

From a practitioner viewpoint, when considering both the HFSSM and the EU-SILC measure time frames, some participants working in the community with those in food poverty suggested that a shorter reference time would be useful to allow practitioners, when visiting a home, an immediate assessment of whether it was thought to be vulnerable to or experiencing food poverty. The literature provides examples of a rapid approach to food insecurity measurement being used in practitioner settings (Bjorney Urke et al., 2014; Knowles et al., 2016; Swindle et al., 2012); however rather than altering the recall time, these studies altered the number of questions posed, using only two questions taken from the HFSSM rather than using the full module. Using a two-item questionnaire has been found to be a feasible, useful approach in health care/social service settings when time is limited (Bjorney Urke et al., 2014; Knowles et al., 2016; Swindle et al., 2012). Stakeholders’ suggestion that in a practical setting measurement should be rapid, and examples in the literature of measurement modules being adapted for practitioner use, indicate that a measure that is useful for government to inform policy and targets may not be as useful on a practical level for those working in the community, who may prefer a more practical measure. Further, those experiencing food insecurity could help inform phrasing of questions which is understandable to all, and inclusion of concepts that are relevant to the lived food insecurity experience.

Results from this study showed that using a headline indicator similarly to fuel poverty (i.e. food expenditure as a proportion of household income) (Liddell et al., 2012), although thought useful to provide a streamlined message and get media and policy maker attention, was largely thought to be insufficient in capturing the multidimensional nature of food poverty. Further, stakeholders generally opined that the complexity of food spend in comparison to fuel spend makes it more difficult to approximate a headline figure. Certain research has however examined and reported food spend as a proportion of household income, such as the ‘Family Spending in the UK’ survey (ONS, 2019), and an academic study which examined fuel versus food spend as a proportion of household income (Bhattacharya et al., 2003), providing evidence that a headline indicator is not entirely unfeasible. However, measuring food insecurity from a relative perspective in this way has been criticised in the literature (Niemietz, 2010) and would contrast with the move to using subjective indicators. Therefore the finding that stakeholders in the majority did not think a headline indicator was feasible, and that an experiential indicator would be preferable, aligned with the literature.

6 Conclusion

Stakeholders were largely in favour of the HFSSM as opposed to the EU-SILC as they felt it was more relevant to the food insecurity experience and that it was up-to-date and would provide more insight. This research provides a contribution in providing stakeholders’ opinions of EU-SILC and HFSSM measures which can be used to evaluate these modules. It has recently been announced that the HFSSM will be adopted as the chosen indicator to measure food insecurity annually across all UK regions (Butler, 2019), this research therefore endorses this choice. Further, findings from this research provide considerations to inform future appraisal of the HFSSM (in UK regions and elsewhere); for example, inclusion of the child-specific questions in locations (such as the UK) which do not include these, addition of a question relating to the social acceptability dimension of the food insecurity experience, use of the term ‘balanced meals’, and cultural or ethnic relevance.

For those countries across the EU which continue to use the EU-SILC food deprivation measures to assess food insecurity, it is recommended, based on the findings of this research, that this approach be re-evaluated, and these questions potentially updated. This recommendation is based upon stakeholder opinions that the EU-SILC questions are perhaps out of date or not fully relevant to the food insecurity experience.

Although findings from one region of the UK (NI) have assumed applicability to other regions of the UK, as well as to other developed regions elsewhere, it is recommended that further research would verify these findings regarding both indicators among other samples and in other locations. This research could be replicated in other regions in the UK, and outside of the UK in locations where these indicators are used. In addition to gaining opinions on the indicators from stakeholders with a similar profile to the sample in the current study, it may be useful to also gather opinions on indicator terminology from those with lived experience of household food insecurity, building on the work of Furey et al. (2019) who examined same in NI.

Finally, although some stakeholders strongly endorsed a quantitative headline indicator providing the rationale that a clear figure is needed to get public, media and policy attention to campaign for change, and to ultimately implement measures to improve the situation, stakeholders largely agreed this approach was not sufficient. It was thought that there was a need for more experiential questions and that it was important not to exclude from a measure consideration of the social exclusion aspect associated with food insecurity. Further, it was thought that it would be a complex measure to construct, with a high degree of error. Therefore this research does not recommend further steps towards a headline approach and instead endorses use of existing experiential measurement approaches, such as the HFSSM.

Data Availability

The data from this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical constraints.

References

Alkire, S., Apablaza, M., & Jung, E. (2014). Multidimensional poverty measurement for EU-SILC countries. OPHI Research in Progress: Oxford University, 36c.

Archer, C., Gallegos, D., & McKechnie, R. (2017). Developing measures of food and nutrition security within an Australian context. Public Health Nutrition, 20(14), 2513–2522. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017001288

Arora, V. S., Karanikolos, M., Clair, A., Reeves, A., Stuckler, D., & McKee, M. (2015). Data resource profile: The European Union statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC). International Journal of Epidemiology, 44(2), 451–461. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv069

Beacom, E., Furey, S., Hollywood, L., & Humphreys, P. (2020). Investigating food insecurity measurement globally to inform practice locally: A rapid evidence review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1798347

Beacom, E., Furey, S., Hollywood, L., & Humphreys, P. (2021). Stakeholder-informed considerations for a food poverty definition. British Food Journal, 123(2), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-03-2020-0237

Bhattacharya, J., DeLeire, T., Haider, S., & Currie, J. (2003). Heat or eat? Cold-weather shocks and nutrition in poor American families. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 1149–1154.

Bickel, G., Nord, M., Price, C., Hamilton, W., & Cook, J. (2000). Guide to measuring household food security. USDA. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/FSGuide.pdf

Bjorney Urke, H., Cao, Z. R., & Egeland, G. M. (2014). Validity of a single item food security questionnaire in Artic Canada. Pediatrics, 133(6), e1616-1623. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3663

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Butler, P. (2019). UK hunger survey to measure food insecurity. The Guardian. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/feb/27/government-to-launch-uk-food-insecurity-index

Caraher, M., & Furey, S. (2018). The economics of emergency food aid provision: A financial, social and cultural perspective. Palgrave Macmillan.

Coleman-Jensen, A. J. (2009). U.S. Food insecurity status: toward a refined definition. Social Indicators Research, 95, 215–230.

Coleman-Jensen, A., Gregory, C., & Rabbitt, M. (2015). Food security in the US. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/survey-tools.aspx#household

Crawford, B., Yamazaki, R., Franke, E., Amanatidis, S., Ravulo, J., Steinbeck, K., Ritchie, J., & Torvaldsen, S. (2014). Sustaining dignity? Food insecurity in homeless young people in urban Australia. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 25(2), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE13090

DECC: Department of Energy and Climate Change. (2019). Annual fuel poverty statistics in England, 2019 (2017 data). Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/829006/Annual_Fuel_Poverty_Statistics_Report_2019__2017_data_.pdf

Department of Health. (2019). Health survey Northern Ireland. Retrieved November 12, from https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/topics/doh-statistics-and-research/health-survey-northern-ireland

Department of Health. (2021). Health survey Northern Ireland: first results 2019/20. Retrieved January 10, 2022, from https://www.healthni.gov.uk/publications/health-survey-northern-ireland-first-results-201920.

End Hunger. (2019). Campaign win! UK Government agrees to measure household food insecurity. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from http://endhungeruk.org/campaign-win-uk-government-agrees-to-measure-household-food-insecurity/

Fuller, E., Bankiewicz, U., Davies, B., Mandalia, D., & Stocker, B. (2019). The Food and You Survey – Wave 5. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/food-and-you-wave-5-combined-report.pdf

Furey, S., Beacom, E., McLaughlin, C., Quinn, U., & Surgenor, D. (2019). The issue of food poverty. Unpublished presentation at: UUBS Food Poverty Forum, January 9, 2019, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Grimaccia, E., & Naccarato, A. (2019). Food insecurity individual experience: A comparison of economic and social characteristics of the most vulnerable groups in the world. Social Indicators Research, 143, 391–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1975-3

Grimaccia, E., & Naccarato, A. (2020). Food insecurity in Europe: A gender perspective. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02387-8

Groves, R. M., Fowler, F. J., Jr., Couper, M. P., Lepkowski, J. M., Singer, E., & Tourangeau, R. (2009). Survey methodology (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Guo, Y., Berrang-Ford, L., Ford, J., Lardeau, M. P., Edge, V., Patterson, K., IHACC Research Team, & Harper, S. L. (2015). Seasonal prevalence and determinants of food insecurity in Iqaluit, Nunavut. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v74.27284

Hagenaars, A., & de Vos, K. (1988). The definition and measurement of poverty. The Journal of Human Resources, 23(2), 211–221.

Healy, A. E. (2019). Measuring food poverty in Ireland: The importance of including exclusion. Irish Journal of Sociology, 27(2), 105–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/%2F0791603519828313.

Huet, C., Ford, J., Edge, V., Shirley, J., King, N., IHACC Research Team & Harper, S. L. (2017). Food insecurity and food consumption by season in households with children in an Arctic city: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4393-6

Husz, I. (2018). ‘You would eat it if you were hungry’ Local perceptions and interpretations of child food poverty. Children and Society, 32, 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12274

Ip, E. H., Saldana, S., Arcury, T. A., Grzywacz, J. G., Trejo, G., & Quandt, S. A. (2015). Profiles of food security for US farmworker households and factors related to dynamic of change. Public Health Nutrition, 105(10), e42–e47. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302752

Kharisma, V., & Abe, N. (2020). Food insecurity and associated socioeconomic factors: Application of Rasch and binary logistic models with household survey data in three megacities in Indonesia. Social Indicators Research, 148, 655–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02210-z

King, G., Lee-Woolf, C., Kivinen, E., Hrabovski, G., & Fell, D. (2015). Understanding food in the context of poverty, economic insecurity and social exclusion. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/FS307008%20-%20Food%20Poverty%20Final%20Report.pdf

Knowles, M., Rabinowich, J., de Cuba, S. E., Cutts, D. B., & Chilton, M. (2016). “Do you wanna breathe or eat?’’: Parent perspectives on child health consequences of food insecurity, trade-offs, and toxic stress. Maternal Child Health Journal, 20, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1797-8

Leroy, J. L., Ruel, M., Frongillo, E. A., Harris, J., & Ballard, T. J. (2015). Measuring the food access dimension of food security: A critical review and mapping of indicators. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 36(2), 167–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572115587274.

Liddell, C., Morris, C., McKenzie, S. J. P., & Rae, G. (2012). Measuring and monitoring fuel poverty in the UK: National and regional perspectives. Energy Policy, 49, 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.02.029

Mahmood, T., Yu, X., & Klasen, S. (2019). Do the poor really feel poor? Comparing objective poverty with subjective poverty in Pakistan. Social Indicators Research, 142, 543–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1921-4

Martinez, S. M., Frongillo, E. A., Leung, C., & Ritchie, L. (2020). No food for thought: Food insecurity is related to poor mental health and lower academic performance among students in California’s public university system. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(12), 1930–1939. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318783028.

Maxwell, S. (1996). Food security: A post-modern perspective. Food Policy, 21(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9192(95)00074-7

Miles, M. B., Huberman, M. A., & Saldana, J. (2013). Qualitative data analysis: A methods handbook (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Niemietz, K. (2010). Measuring poverty: Context-specific but not relative. Journal of Public Policy, 30(3), 241–262. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X10000103

O’Connell, R., Owen, C., Padley, M., Simon, A., & Brannen, J. (2019). Which types of family are at risk of food poverty in the UK? A relative deprivation approach. Social Policy and Society, 18(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746418000015

O’Connor, N., Farag, K., & Baines, R. (2016). What is food poverty? A conceptual framework. British Food Journal, 118(2), 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-06-2015-0222

ONS. (2019). Family spending in the UK: April 2017 to March 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/expenditure/bulletins/familyspendingintheuk/financialyearending2018

Palmeira, P. A., Bem-Lignani, J., Maresi, V. A., Mattos, R. A., Interlenghi, G. S., & Salles-Costa, R. (2019). Temporal changes in the association between food insecurity and socioeconomic status in two population-based surveys in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Social Indicators Research, 144(3), 1349–1365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02085-0

Perić, N., Hofmarcher, M. M., & Simon, J. (2018). Headline indicators for monitoring the performance of health systems: Findings from the European Health Systems_Indicator (euHS_I) survey. Archives of Public Health, 76(32), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-018-0278-0.

Purdy, J., McFarlane, G., Harvey, H., Rugkasa, J., & Willis, K. (2007). Food poverty: fact or fiction? Public Health Alliance.

Radimer, K. L., Olson, C. M., & Campbell, C. C. (1990). Development of indicators to assess hunger. Journal of Nutrition, 120(11), 1544–1548. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/120.suppl_11.1544

Radimer, K. L., Olson, C. M., Greene, J. C., Campbell, C. C., & Habicht, J. P. (1992). Understanding hunger and developing indicators to assess it in women and children. Journal of Nutrition Education, 24(1), 36S-44S. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3182(12)80137-3

Rafiei, M., Nord, M., Sadeghizadeh, A., & Entezari, M. H. (2009). Assessing the internal validity of a household survey-based food security measure adapted for use in Iran. Nutrition Journal, 8(28), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-8-28

Saldana, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Sharpe, L. (2016). Time to count the hungry: the case for a standard measure of household food insecurity in the UK. Retrieved September 10, 2019, from https://foodresearch.org.uk/roundtables/mapping-the-way-forward-on-food-poverty/

Smith, D., Thompson, C., Harland, K., Parker, S., & Shelton, N. (2018). Identifying populations and areas at greatest risk of household food insecurity in England. Applied Geography, 91, 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.12.022

Swindle, T. M., Whiteside-Mansell, L., & McKelvey, L. (2012). Food insecurity: Validation of a two-item screen using convergent risks. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(7), 932–941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9652-7

Tarasuk, V. (2016). Advancing food insecurity research in Canada. In Advancing food insecurity research in Canada, 17–18 November 2016, Toronto. Retrieved September 20, 2019, from https://proof.utoronto.ca/conference/

Thompson, C., Smith, D., & Cummins, S. (2018). Understanding the health and wellbeing challenges of the food banking system: A qualitative study of food bank users, providers and referrers in London. Social Science and Medicine, 211, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.030

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom: A survey of household resources and standards of living. Penguin.

UNICEF. (2014). Children of the recession: the impact of the economic crisis on child well-being in rich countries. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/rc12-eng-web.pdf

Veenhoven, R. (2002). Why social policy needs subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, 58(1–3), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015723614574

Webb, P., Coates, J., Frongillo, E. A., Rogers, B. L., Swindale, A., & Bilinsky, P. (2006). Measuring household food insecurity: Why it’s so important and yet so difficult to do. The Journal of Nutrition, 136(5), 1404S-1408S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.5.1404S

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium. This research was funded by the Department for Employment and Learning, Northern Ireland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Emma Beacom. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Emma Beacom and all authors commented on, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics Approval

Ethical permission was sought and granted from Ulster University Research Ethics Committee.

Consent to Participate

Participants provided both written and verbal informed consent.

Consent for Publication

Participants provided written consent for anonymised quotes to be published.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Appendix 1: Interview Topic Guide

Measuring food poverty

Unlike fuel poverty, food poverty does not have a government endorsed definition or measurement.

Do you think that there is merit in food poverty having a nationally agreed definition* and measurement or do you think it is adequate to continue to consider food poverty as an element of poverty more generally?

A household is said to be in fuel poverty if they spend over 10% of their income on fuel. Do you think a similar headline indicator would adequately measure household food poverty?* What are the advantages/disadvantages of this approach?

Do you think that food poverty should be measured consistently over time in Northern Ireland and the UK? Why or why not?/Do you think there is merit in measuring food poverty?/What do you think is the merit in measuring food poverty if any?

Can you think of any examples of when or where food poverty has been measured successfully? If not no problem.

If we were to measure food poverty in Northern Ireland or the UK, what factors can be measured or what factors should be considered when putting together a measure?

-

Do you think that a food poverty measure should include a severity scale (eg) slight/moderate/severe?

[Show Cue card 3 - the HFSSM and EU-SILC measures]

I’m very interested in getting your opinion on these two existing measures of food poverty. The first is a set of measures taken from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions, and these measures are what is currently used to measure food poverty in Northern Ireland (since 2013 they have appeared in the Health Survey for Northern Ireland. The second set of measures (the Household Food Security Survey Module) is a measure which is routinely used in Canada and the United States, and which has been adapted for some other cultures across the world. Some of these questions have also been used in the Health Survey for Northern Ireland alongside the EU-SILC measures. The HFSSM is a longer measure but is split into screening sections according to severity and according to whether or not there are children in the household, so although it seems long food secure households would only answer the first few questions and then would bypass the rest.

What are your opinions on these two measures?

-

How do you think they compare? Is one superior to the other? If yes, why? If no, why not?

-

Which one do you think would measure food poverty more accurately?

-

Is there anything you think these measures are missing?

-

Do you think these measures would be easily understood and answered by consumers or can you see any potential problems with them?

What do you think the advantages would be of measuring food poverty?

What do you think the barriers would be to measuring food poverty?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beacom, E., Furey, S., Hollywood, L. et al. Food Insecurity Measurement: Stakeholder Comparisons of the EU-SILC and HFSSM Indicators and Considerations Towards the Usefulness of a Headline Indicator. Soc Indic Res 162, 1021–1041 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02865-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02865-7