Abstract

Is it possible to identify a ‘riches line’, distinguishing the ‘rich’ from the ‘super-rich’? Recent work in political philosophy suggests that this is theoretically possible. This study examines for the first time the empirical plausibility of a riches line, based on novel data collected from a representative sample of the Dutch population. The data reveal that the Dutch indeed draw such a line, namely between 1 and 3 million euros. Strikingly, respondents agree on its approximate location irrespective of their own income and education. Although most do not consider extreme wealth itself a severe problem and object to the government’s enforcement of limits to wealth and income, widespread support exists for increased taxation of the super-rich if that would improve the quality of life of the most vulnerable members of society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Recent years have seen much discussion of inequality, in academia as well as outside academia. The Occupy movement that in 2012 mobilized mass protests worldwide against wealth disparities spurred subsequent debate among leading economists (Mankiw 2013). In 2014, the discussion was centered around Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century, in which he documented the rise in inequality and, in particular, the strengthened position of the wealthiest (Piketty 2014). More recently, the book The Triumph of Injustice by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, has argued how in the USA recent fiscal policies have increased inequality at the top of the income- and wealth distribution, hence consolidating the position of the richest Americans (Saez and Zucman 2019). In politics too, policies targeting the superrich are increasingly being discussed. In 2019, a proposal by the US-Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio Cortez to raise a 70% marginal tax rate on incomes above 10 million dollars was followed by heated political discussion and further academic debate (Saez and Zucman 2019; Krugman 2019).Footnote 1 At the time of writing (first half of 2020), several candidates for the Democratic nomination for the next US presidential elections are proposing wealth-taxes on the extremely rich.

At the same time, philosophers have taken these redistributive proposals one step further, and have argued that, analogous to a poverty line under which no one should ideally fall, one can also conceptualize a riches line above which one owns or earns too much (Robeyns 2017, 2019; Volacu and Dumitru 2019; Zwarthood 2018; Timmer 2019). What follows from this philosophical work are both an evaluative and a normative claim. The evaluative claim is that members of a society can agree on the approximate location of a line between the rich and those who have much more than needed to lead a fully flourishing life. The normative claim is that institutional (including fiscal) measures should be taken to move in the direction of a situation where no one lives above the riches line.

We move beyond philosophical research by investigating for the first time whether the evaluative claim stands up to empirical scrutiny, and whether the normative claim is met with support from the members of a society. To this end, we designed a vignette-based questionnaire uniquely aimed at gaining evidence regarding a riches line and gathered this data for a representative sample of the Dutch population.

Our aim is to find answers to two questions. The first is whether a riches line can be drawn, similar to a poverty line, and where to draw it. We conceptualize this riches line, and then test whether it can instead be validated in a wealthy country. This boils down to the question whether we can distinguish the rich from the super-rich.

The second question is whether citizens believe that such a riches line should be enforced by their government. In other words, we ask whether this is a limit people think no one should be allowed to exceed and that it should therefore be enforced. From a fiscal perspective, this would mean levying a 100 per cent tax on wealth or inheritances exceeding a particular amount. From a ‘pre-distribution’ perspective, this would mean taking measures to prevent large pre-taxation differences in wealth from arising, such as the introduction of maximum wages or applying highly progressive tax rates to profits.

2 Background

Identifying a riches line can be seen as the symmetrical exercise from identifying the poverty line. Anyone situated below the poverty line has not enough resources to enjoy a minimal standard of living, whereas anyone situated above the riches line has more resources than one needs to maximally flourish. The literature on the construction of the poverty line has also been an important source of information and inspiration for the research that is presented in this paper. It is obvious that poverty measurement is by now a very developed field of empirical analysis. For one thing, the vast scientific literature on poverty lines shows that they can be constructed in different ways (Sen 1983; Atkinson 1987; Foster 1998). To mention just two of the many developments, we can note that there is a growing literature that measures poverty with multidimensional metrics (e.g. Dewilde 2004; Alkire and Santos 2013; Batana 2013; Alkire et al. 2015; Nowak and Scheicher 2017). Another refinement in the poverty measurement literature is to measure poverty for specific subgroups, such as poverty among children (e.g. Roelen et al. 2010; Chzhen and Ferrone 2017; Stewart and Roberts 2019).

However, we cannot simply copy the poverty line and apply it to the other side of the distribution, since we are measuring different concepts. Moreover, we cannot simply assume that the level of consensus that can be reached on the question what poverty is, can also be reached on the question when we regard someone as too rich. In this paper, we therefore take a first step in the measurement of the riches line, whereby we investigate where the population itself would draw that line.

Interestingly, in an almost entirely forgotten paper published in Social Indicators Research, Jan Drewnowski (1978) argued for what he called an ‘affluence line’, which he defined as “the line above which consumption need not and should not rise” (Drewnowski 1978, 264). He argued that we needed an affluence line because it would be a better allocation of resources, because social justice required it since no-one could claim to deserve so much, and because excessive affluence would lead to social evils such as “deterioriation of common honesty standards” and “the decline of a sense of duty among the leading and most affluent professions” (Drewnowski 1978, 267). Drewnowski argues that the affluence line should be conceptualized in terms of when objective needs are fully satisfied, and that expenditures above those standards have no merits for the individual. The approach we take in this paper is to a very large extent congruent with Drewnowski’s general proposal for an upper limit to affluence. Yet in contrast to Drewnowski’s general outline of the idea, we put the idea to an empirical test: can we, in a methodologically sound way, empirically establish a riches line, and is this idea of a riches line also endorsed by present-day populations who grew up in a capitalist society? As we will show in what follows, both questions can be answered affirmatively. Also, Medeiros (2006) defines and actually tests an affluence line for Brasil, but he does not use the judgements of people themselves but instead relies on macro-economic data about incomes. So does Concialdi (2018) in a more recent paper. They both apply rules that do not rely on the definition of perceived affluence in absolute terms. We are interested in the judgement of people themselves about what they consider rich.

To measure the riches line, we follow the theoretical account as developed by Ingrid Robeyns (2017), drawing the line at the point where one additional monetary unit (income or wealth) cannot expand an individual’s “flourishing”, conceptualized as an objective account of material quality of life. Robeyns (2017, 25–26) argues that non-material dimensions of the quality of life should not be included in the construction of a riches-line, because ‘being rich’ needs to be distinguished from scoring high or low on immaterial dimensions of the quality of life. For example, a black or female American lawyer may be very rich, while also being faced with racism or sexism. Robeyns’s argument is that while surely being discriminated against is unjust and lowers a person’s overall quality of life, it doesn’t make a rich person non-rich. Whether or not one is poor, decently off, or rich, is only one dimension of life that matters. The question on the table is how to distinguish the rich from the super-rich, and for this question we need to draw a line on a metric of material quality of life.

Concretely, the conceptualization of this metric goes as follows. Each person has a certain material quality of life: the quality of her housing, her access to transport, food, clothing, basic amenities, and so forth. At low levels of material quality of life, we define a minimal set that a person must have access to in order to not count as poor. At the other opposite of the distribution, the riches line is the point at which additional money cannot add to the material quality of life of a person. What is the point in the wealth distribution where a person or a family may be able to buy another car, or buy a still larger house, or still further increase its savings and assets, yet where this can arguably be seen not to lead to a further increase of her quality of life? Put differently, if a portion of an individual’s wealth does not contribute to a higher quality of life, then that individual is living above the riches line and has much more than needed for leading a fully flourishing life.

Given the lessons that can be learnt from the vast literature on the poverty line, we should pause to ask why we do not measure the riches line in a relative way. After all, there is a huge debate on whether poverty should be measured in an absolute or a relative way (Townsend 1979; Sen 1983; Foster 1998; Ravallion and Chen 2011). We believe that there can be reasonable disagreement on whether one should measure poverty in a relative or absolute way, and similar reasonable disagreement exists for the riches line.

The choice for an absolute line flows from our theoretical basis, namely the theoretical riches line conceptualized by Robeyns (2017). In that theoretical piece, Robeyns (2017, 15–20) argues for an absolute riches line. She argues that relative poverty/riches lines are insensitive to a shift in the income distribution. In the poverty literature, the importance of this argument has also been illustrated empirically by Ravallion and Chen (2011) who showed that with economic growth, the number of absolutely poor fell while the number of relatively poor rose. A relative riches line could not account for a society in which all have modest standards of living, and then, e.g. due to the discovery of an extremely valuable economic resource all become significantly better off. In addition, we need to distinguish between being the person who has the best position in material terms, which is a comparative notion that could be captured by a relative riches line, and being rich, which is an absolute notion that we are interested in here.

However, Robeyns captures from the discussion on relative versus absolute poverty lines another insight, which she argues should be used in the development of a riches line. Her arguments just mentioned entail reasons not to opt for a distribution-relative measure, which “define riches or poverty as being at a certain distance from the average of the distribution.” (Robeyns 2017, 18). However, she does accept the rationale for context-relative or contextual measures, which means that the concept does refer to the context (time and space, hence the particular society in which one lives). She gives the example that in Western Europe owning a non-luxurious new car doesn’t in itself make one rich, but that this might be the case in other areas of the world. One implication of adopting a distribution-insensitive but context-sensitive measure of riches is that the methodology we offer should be adapted to different contexts in which it could be applied. We will return to this point when we elaborate on the empirical design.

Now that we have established the conceptualization of the riches line, we need to test whether the riches line is merely a theoretical yet unmeasurable construct, or whether it can instead be validated in a wealthy country. Simply asking people where to draw such a line would be too difficult for them. A better way is to contextualize a possible riches line by using vignettes. Vignettes present a hypothetical real life situation in which respondents can imagine themselves or other people so that they are able to genuinely respond to the questions asked about the vignettes. In our case, the vignettes contain descriptions of families including indicators of their standard of living. These typically include the level of wealth, material goods, and luxury consumption. Respondents are then asked how they evaluate the richness of these families. We think that the concrete descriptions help respondents to provide these evaluations and we have tried to create descriptions that provide enough variation around the point where respondents distinguish between rich and super-rich. Below we provide the details of the vignette design and we will later evaluate to what extent we think we succeeded in reaching these measurement goals.

3 Data and Methods

The survey, consisting of a vignette study and measures of agreement with a series of statements, was conducted among members of the LISS Panel (Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences).Footnote 2 The LISS Panel is a true probability sample of households drawn from the population register by Statistics Netherlands, and as such representative of the Dutch population. The survey was sent to 3350 panel members in 2018. A total of 2561 respondents (76 per cent) completed the questionnaire.

To determine whether respondents agreed on where to draw the line between rich and extremely rich, the survey presented them with specific example situations—‘vignettes’. Ten vignettes were designed, each describing a hypothetical family’s standard of living; containing information about their home, second home (if any), cars, holidays, and savings. They are displayed in Table 1.

The items listed in the vignettes are aspects of the standard of living and material inequalities that make up the bulk of the dimensions that inequality studies in the Netherlands look at, including studies and periodic analyses by research agencies that are tasked by the Dutch government to analyze material inequalities in the Netherlands (SCP 2019; WRR 2014). It is quite possible that the concrete selection of the dimensions, and hence the description of the vignettes we used, are specific to the Netherlands. For example, the Dutch welfare state has a universal pension system (only condition on years of legal residency in the Netherlands) as well as additional pension saving schemes as a standard social right in almost all sectors of the labor market. It also has a high-quality public health care system that is accessible to all residents. In countries that lack these properties, one might consider adding pension rights or having good health care insurance as a relevant dimension of the material standard of living, yet in the Netherlands these items would add little information.

This series of qualitative descriptions was used so that respondents could envision each hypothetical family rather than evaluate an abstract quantity. In addition, it allows us to identify the contributions of different dimensions of wealth to individuals’ overall assessments of family wealth. It would be more difficult for respondents to come up with a number themselves on what they would consider extremely rich (Van Schuur 2003).

Respondents were asked to assess the standard of living of each family, choosing from an ordered set of five answers, ranging from ‘just enough to get by’ to ‘extremely rich’:

Just enough This family has just enough to get by. They can never permit themselves any luxury.

Reasonable This family has enough to live on. They can afford some luxury now and then, but they could certainly lead a better life if they had some extra money.

Good This family is not lacking anything. They have a good life and can afford to do plenty of nice things, but they have to consider carefully before spending larger amounts on luxury.

Rich This family has more than they need to lead a good life. They rarely have to consider whether they can afford larger luxury spending.

Extremely rich This family has much more than they need to lead an affluent life. They never have to consider whether they can afford certain luxury spending, and even then, they still have plenty of money left to do extraordinary things that almost no one can afford. No one needs that much luxury.

3.1 Construction of a Scale Variable

Because we are interested in the riches line, we are particularly interested in whether a respondent considered a family extremely rich. Therefore, the ten items are recoded into dummy variables indicating whether a family was considered extremely rich. The vignettes were ordered such that with each successive vignette, one or more of these parameters increased in value or luxury standard, thus reflecting families with progressively greater wealth. Respondents could thus be expected to rate wealth in each successive vignette at least as high as in the preceding vignette: If one considers a family with some possessions rich, then if another family has those same possession plus other possessions, the latter family should not be considered less rich than the former. If we assume such monotonicity, whereby richness assessments are non-decreasing in possessions, then the vignettes together form a Mokken scale, a unidimensional scale that consists of hierarchically-ordered items that measure the same underlying, latent concept (Mokken 1997).

We evaluated whether the items form a Mokken scale. When we include all items in the scale, we obtain a Loevinger’s H of 0.94, which indicates an extremely strong scale confirming that most respondents’ answers satisfy the monotonicity property. This was indeed true for 95 per cent of the respondents. The Mokken scale analysis shows that the scale becomes even better (Loevinger’s H = 0.96) if we exclude the first (least rich family) and the last two (most rich families) from the scale. This happens because non-monotonic responses are relatively prevalent among respondents who considered the first family already extremely rich or the last two families not yet extremely rich. Therefore, we will indeed drop the three items that fit less well into the scale for further analysis. We also performed all the analyses on the scale consisting on all ten items, but no substantive differences were found for that scale. Hence, at the respondent’s level, we construct a variable riches line 1 as a count of the number of families from family 2 until family 8 that someone considers extremely rich. In addition, riches line 2 is a count of the number of all families that someone considers extremely rich, which is then used for the robustness check; the correlation between these two variables is 0.985. Table 2 provides summary statistics about the vignette families, the two operationalizations of the riches line and the key demographic variables used below. Education is measured at a six point scale (primary education, lower vocational, pre-college secondary education, higher vocational, college degree, university degree). Income is measured as gross income in 14 categories (0 is no income).

3.2 Construction of a Monetary Variable

To quantify the riches line, we aggregated the six features of each vignette into a total wealth amount. We translated our vignettes into a number that quantifies the wealth the vignette represents, representing each vignette element with a euro amount. We worked with Dutch price levels in euros because the respondents were Dutch. We determined each respondent’s riches line as the total wealth level of the least wealthy vignette characterized as ‘extremely rich’. Table 3 illustrates how this conversion was achieved.

4 Results

4.1 The Evaluative Claim

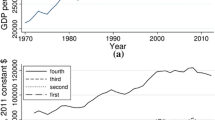

The evaluative claim we test is that members of a society can agree on the approximate location of a line between the rich and those who have much more than needed to lead a fully flourishing life. Nearly all Dutch people draw some line between a family that is ‘rich’ and a family that is ‘extremely rich’. The left panel in Fig. 1 shows the percentage of respondents who judge each family to be ‘extremely rich’. Less than four per cent of the respondents decided that none out of the ten families can be labelled ‘extremely rich’. This indicates that for nearly all subjects the riches line lies within the range of wealth levels presented to them. Important triggers seem to be having a second house, a swimming pool or reaching the 1 million euro savings.

The vignettes show that two-thirds of the population described the wealth of the top half of families (six through ten) as ‘extremely rich’, while only a minority includes any family below six, thus placing the median halfway the Mokken scale (in Fig. 1, the dashed line in boldface). One concern may be that our set of vignettes suggested to respondents that the riches line had to lie somewhere in the given range. However, respondents did not reserve the most extreme qualification of wealth for just the one or two most extreme example families. Indeed, the distribution of responses was so skewed that the majority qualified the wealth of all families as being at least ‘good’ (category 3) and the wealth of all but the two poorest families as at least ‘rich’ (category 4). This severe skew suggests that had we excluded some of the wealthiest vignettes or included poorer ones, the data would have continued to suggest the same riches line.

Figure 1 displays the observed distribution of respondents’ riches lines expressed in total wealth (closed circles) as well as its geometric mean, 2.2 million euros. The figure reveals striking agreement among most respondents that the riches line lies between 1 and 3 million euros. Practically no one considered the vignettes with wealth levels below 1 million euros extremely rich, yet at a little over 2 million for a majority the riches line has already been crossed, while at 3 million a broad consensus has been reached. For comparison, we added the distribution that would have resulted from respondents drawing a riches line at a randomly chosen vignette (open circles). A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test confirms that the empirical distribution is significantly different (p < 0.001).

While Fig. 1 shows general consensus on the riches line lying between 1 and 3 million, some respondents do draw it substantially higher. One might wonder whether the place where the riches line is drawn depends on demographics of the respondents. Table 4 shows the geometric mean for subjects with varying income, education, gender, and age. Women and younger people draw the riches line lower, while those with higher incomes and those with a college degree place it higher. Still, all subgroups place the riches line a little above 2 million euros.

To explore the extent to which Dutch society is divided in its judgments on the location of the riches line across basic demographic lines we performed multiple regression analysis, predicting the location of the riches line from respondent demographics. The dependent variable is the second Mokken scale “riches line 2” discussed in the previous section. As independent variables we include gender as a dummy variable (1 = female, 0 = male) and age as an interval variable. In addition we include Income in categories as an interval variable using categories 1–10 for 500 euro categories up to 5000 euro gross household income, category 11 for between 5000 and 7500 euro and category 12 for over 7500 euro gross income. We add also a dummy for respondents who did not share information on their income. We use a categorical variable for level of education as a linear predictor with an extra control dummy for respondents with only primary education, because that category stands out a bit in its relation with the riches line. Alternative choices with regards to variable operationalization do not impact the substantive results.

Table 5 shows the results of the regression analysis. A positive coefficient implies that the riches line is placed at a lower level of wealth (more families are categorized as extremely rich). Overall, demographics matter remarkably little. While some subgroup differences are statistically significant, only about 2 percent of the variance can be attributed to these properties. Women place the riches line at a lower level as well as younger people, and people with lower education. The exception is the relatively small group of people with only primary education, who set the riches line at a higher level. There is a weak tendency for people with a higher income to place the riches line at a higher level, while people who do not provide information on their income place it at a lower level. The effects of income largely disappear after controlling for age. Overall, effects are substantively small, with differences between demographic categories always falling well below 1, meaning that the typical member of each group draws the line near the same family, namely family 5. It is particularly striking that respondents agree on the approximate location of the riches line largely irrespective of their own income and education.

4.2 The Normative Claim

We have found strong support for the evaluative claim: Not only can a riches line be established in theory; the vignette study shows that a riches line can also be established empirically. If a specific example is given of how people live, then the Dutch do draw a distinction between the ‘rich’ and the ‘extremely rich’, and are even able to give a precise figure for where the riches line lies. In essence, the riches line is—as is also the poverty line—a social construct: something citizens can debate and policy makers can decide upon, together with input from experts. In such a discussion, not only scientists may contribute, but possibly also those who have experience with living in poverty. As we indicated in the introduction, the vast scientific literature on poverty lines shows that they can be constructed in different ways. The same goes for a riches line. For instance, when constructing a riches line on the basis of public opinion, we must decide whether it is enough for two-thirds of the population to see a certain standard of living as ‘extremely rich’, or whether instead a broader consensus is needed. The information from our vignette study must therefore be combined with a judgement on how much endorsement from the population is required.

While the evidence suggests a riches line can be drawn, analogous to a poverty line, this does not imply that the respondents believe that such a line should also be taken as norm or ideal. We may be able to identify an agreed-upon line between ‘rich’ and ‘extremely rich’, but we do not know if people also find that the government has a legitimate task in reforming economic institutions to keep people below it. The normative claim we seek to test is that institutional (including fiscal) measures should be taken to move in the direction of a situation where no one lives above the riches line.

We gauged normative support for a riches line by soliciting respondents’ attitudes toward a series of normative statements. The respondents were asked whether they wanted to see limits placed on income, wealth, and inheritances, and whether they approved of a range of hypothetical instruments the government could use to limit inequality at the top of the income and wealth scale. Table 6 contains the answers to four statements of a relatively abstract nature.

The levels of agreement with these abstract statements show that most people in the Netherlands do not necessarily see extreme riches as a problem. We also presented respondents with more concrete statements, divided into three categories: firstly, a statement more specifically describing the life of a very rich person; secondly, a statement about what is generally seen as an undesirable societal phenomenon that could be the consequence of extreme riches; and thirdly, a statement about government interventions aimed at reducing poverty and deprivation via redistribution. Levels of agreement with these statements are presented in Table 7. For each of these more concrete statements, respondents tended much more towards normative support for a riches line.

Tables 6 and 7 reveal a striking discrepancy between the answers given to abstract and concrete statements about the desirability of extreme riches. When given abstract statements, a vast majority indicate not to have a problem with extreme wealth, as long as it is acquired fairly. Yet when presented with a concrete case of extreme wealth, Jeff Bezos, more people see it as a problem for society than those who don’t. Perhaps this is because respondents believe that Jeff Bezos did not earn his money in a fair way, or because they think that, in general, it is impossible to accumulate so much wealth fairly. Alternatively, these results might be due to the specific—rather than abstract—nature of the questions, leading to more skeptical judgments of extreme wealth.

Many respondents indicate that they do not think that the extremely rich should be able to exert more influence on politicians than those who are less rich. Political philosophers name this greater influence as a primary reason to keep extreme wealth within limits (Rawls 2009; Christiano 2012; Robeyns 2017; Timmer 2019). If a vast majority of a population is against the rich having more political influence, and these views are supported by valid arguments from ethics and philosophy, then people will be more likely to identify this problem in practice.

Only a small percentage of respondents are in favor of measures to cap income, inheritance or wealth; the vast majority are not in favor of such limits. However, if they have to choose between policies that impose higher taxes on the rich and policies that cut services for the most vulnerable in society, then more than two-thirds of the population would support increasing taxes on the rich. This again shows that whether the issue of extreme wealth is placed in context, its consequences for power, democracy, and poverty illuminated, might have an impact on public opinion.

In turns out that all the more or less concrete statements discussed above form a quite reliable scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79). We can add this norm scale (constructed by taking the mean of all 12 items) to the analysis above. This variable has as expected a positive effect. People who are more concerned about income differences place the riches line at a lower level. This variable explains almost 4% of the variance, which is more than all the other variables together (see Table 8).

5 Conclusions and Discussion

The data used in this study is the very first attempt of which we are aware that aims to establishing a riches line using judgements of people using a quantitative approach.Footnote 3 Hence it must be seen as the first in a series of empirical studies looking into the evaluative question of whether society believes that there is an upper limit to how much wealth can contribute to the standard of living of a family, and the normative question of whether society thinks such an upper limit should be reinforced.

The first conclusion is that it is indeed possible to establish a riches line empirically. There appears to be a clear difference what “rich” and “super rich” means for people. Similar to the poverty line, this riches line proves to be a social construct. An implication is that politicians can use the riches line to discuss the level of riches in society, in a similar way as is already done in discussions about the poverty line. The evaluative claim which indicates that people can estimate what is super rich is thus supported. A riches line has already been developed in previous work based on the income distribution (Medeiros 2006; Concialdi 2018). We now have developed one which is based on judgements of people themselves.

The second conclusion is that such a riches line is not necessarily a norm for people. They do not perceive extremely rich people as a problem in itself. When a statement is presented in the abstract, not many people are in support of limiting extreme riches. By the same token, we can also conclude that a larger share of the population has a problem with riches when the statement is made concrete by means of a real-life situation. People thus appear in support of measures to limit riches when presented with specific cases of extraordinary wealth, and also when the societal gains from such limits are made salient. Most people are in support of a tax on the incomes of the super-rich if they are also told what that money will be used for—and if that money benefits the most vulnerable people in society.

The instrument we have shown seems to be able to establish how a certain population (in this case a representative sample of people in the Netherlands) thinks about where a riches line should be and at what point there might even be broad consensus that the riches line is reached. One advantage of our vignette method is that we provide respondents with an illustrative description of wealth of families rather than providing just a number of income or capital. We believe that this way of picturing helps respondents to judge richness more easily. In addition, the data have shown that the vignettes are also rightly chosen: we have quite fine-tuned distinctions around where respondents indicate that the riches line should be, while we also include the extremes where hardly any respondents think such a family is too rich or where almost everyone holds that such a family is too rich.

Clearly, the disadvantage of an illustrative instrument as this is that it is rather context dependent. The descriptions and variations used here might be reasonable for countries that have a similar welfare state infrastructure as the Netherlands. Countries with a significantly different type of welfare state, for example with a health care system or educational system that has a significant private sector, or without public pension provisions, might need to add those items to the vignettes in the questionnaire. In addition, the descriptions should be certainly adjusted if one were to use a similar methodology in less developed countries. This also implies that the outcomes might be used to guide politics within a certain country, but the method is less suitable to guide more global distributional questions. The context-relative nature of the measures we have adopted also implies that when societies change drastically over time, the measure might require adaption. At a methodological level, it should be noted that this vignette based set-up is flexible and easily adaptable to settings that require different variables while the essence of the analyses can remain the same. Finally, it is important to stress that this empirical method reveals the views by a population of people on when a person can be qualified as ‘extremely rich’, but does not directly address normative questions as to what reasons we might have for considering someone too rich, let alone what (if anything) would follow for policies.

Future research should take further steps towards refining the methodology for constructing and measuring the riches line. One question is whether mixed quantitative–qualitative methods, such as Q-methodology, would confirm the appropriateness and validity of quantitative surveys such as the one designed for this study. After we completed our study, a Report was published in which the idea of riches line was tested empirically with focus groups in London (Davis et al. 2020). One interesting line of future research would be to apply both the qualitative methods used in that study with the quantitative methods used in our study, and analyze possible differences in the results.

A second topic for further research relates to the context-sensitivity of absolute riches lines. To what extent does this make comparisons between the phenomenon of ‘superriches’ in different countries difficult, and how exactly? As we argued above, the content of the vignettes needs adapting in case the method we proposed is used in significantly different contexts. But what does this imply for intertemporal and international/interregional comparisons of studies of riches? Are they simply impossible, or are the merely difficult, and if so, what makes them (im-)possible? This study focused on the Netherlands, and it would be very interesting to investigate how the methodology can be generalized for different countries and to study whether it would be possible to quantify by means of an international comparative study to what extent the riches line depends on the economic development, policies and culture of a country.

In addition, subsequent research may probe the robustness of the tentative relationship between descriptive judgements and normative judgements identified here. Others may investigate whether public support for government policies imposing a riches line would be greater if concrete benefits of such policies were specified. Citizens may be unwilling to support policies that limit a person’s wealth if it is unclear what society would gain. Future studies may also make a clearer distinction between inequality generated by processes that people see as unfair and processes experienced as fair, such as income from employment being taxed differently than income from business activity (profit) or from capital gain. People may find ‘fairness’ important, which may not always be the same as ‘equality’ (Starmans et al. 2017).

Notes

For the interview with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez by CBS news https://www.cbsnews.com/news/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-the-rookie-congresswoman-challenging-the-democratic-establishment-60-minutes-interview-full-transcript-2019-01-06/ (last accessed October 10, 2019).

See “Appendix 1” for the complete questionnaire translated into English. The original questionnaire (in Dutch) can be found in “Appendix 2”.

A first descriptive analysis, which didn’t include the statistical analysis and broader embedding in the literature, was presented in Robeyns et al. (2018). More recently, a team conducted an analysis based on London-based focus groups discussing where a riches line could be drawn (Davis et al. 2020).

[3] Note to the translation: ‘Randstad’ is the most urban area in the Netherlands, consisting of the four big cities Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht. It is one of the most densely populated areas in North-Western Europe.

References

Alkire, S., Foster, J., Seth, S., Santos, M. E., Roche, J. M., & Ballon, P. (2015). Multidimensional poverty measurement and analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2013). A Multidimensional approach: Poverty measurement & beyond. Social Indicators Research, 112(2), 239–257.

Atkinson, A. B. (1987). On the measurement of poverty. Econometrica, 55, 749–764.

Batana, Y. M. (2013). Multidimensional measurement of poverty among women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Social Indicators Research, 112(2), 337–362.

Christiano, T. (2012). Money in politics. In D. Estlund (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of political philosophy (pp. 241–257). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chzhen, Y., & Ferrone, L. (2017). Multidimensional child deprivation and poverty measurement: Case study of bosnia and herzegovina. Social Indicators Research, 131(3), 999–1014.

Concialdi, P. (2018). What does it mean to be rich? Some conceptual and empirical issues. European Journal of Social Security, 20(1), 3–20.

Davis, A., Hecht, K., Burchardt, T., Gough, I., Hirsch, D., Rowlingson, K. & Summers, K. (2020). Living on different incomes in London. Can public consensus identify a ‘riches line’? CASE report 127. London: London School of Economics and Political Sciences.

Dewilde, C. (2004). The multidimensional measurement of poverty in Belgium and Britain: A categorical approach. Social Indicators Research, 68(3), 331–369.

Drewnowski, J. (1978). The affluence line. Social Indicators Research, 5(1), 263–278.

Foster, J. E. (1998). Absolute versus relative poverty. American Economic Review, 88, 335–341.

Krugman, P. (2019). Notes on excessive wealth disorder. NYTimes, 21, 16–49.

Mankiw, N. G. (2013). Defending the one percent. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(3), 21–34.

Medeiros, M. (2006). The rich and the poor: The construction of an affluence line from the poverty line. Social Indicators Research, 78(1), 1–18.

Mokken, R. J. (1997). Nonparametric models for dichotomous responses. In W. J. van der Linden & R. K. Hambleton (Eds.), Handbook of modern item response theory (pp. 351–367). New York: Springer.

Nowak, D., & Scheicher, C. (2017). Considering the extremely poor: Multidimensional poverty measurement for Germany. Social Indicators Research, 133(1), 139–162.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the 21st century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ravallion, M., & Chen, S. (2011). Weakly relative poverty. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(4), 1251–1261.

Rawls, J. (2009). A theory of justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Robeyns, I. (2017). ‘Having Too Much’. In NOMOS LVIII: Wealth, edited by Jack Knight and Melissa Schwartzberg, 1–45. Yearbook of the American Society for Political and Legal Philosophy. New York: NYU Press.

Robeyns, I. (2019). What, if anything, is wrong with extreme wealth? Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 20, 251–266.

Robeyns, I., van der Lippe, T., Buskens, V., & Vergeldt, N. (2018). Vinden Nederlanders dat er grenzen zijn aan rijkdom? Economisch-Statistische Berichten, 103(4765), 399–402.

Roelen, K., Gassmann, F., & de Neubourg, C. (2010). Child poverty in Vietnam: Providing insights using a country-specific and multidimensional model. Social Indicators Research, 98(1), 129–145.

Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2019). The triumph of injustice. How the rich dodge taxes and how to make them pay. New York: WW Norton.

SCP. (2019). De Social Staat van Nederland. Den Haag: Sociaal Culturaal Planbureau.

Sen, A. (1983). Poor, relatively speaking. Oxford Economic Papers, 35(2), 153–169.

Starmans, C., Sheskin, M., & Bloom, P. (2017). Why people prefer unequal societies. Nature Human Behavior, 1, 82.

Stewart, K., & Roberts, N. (2019). Child poverty measurement in the UK: Assessing support for the downgrading of income-based poverty measures. Social Indicators Research, 142(2), 523–542.

Timmer, D. (2019). Defending the democratic argument for limitarianism. Philosophia, 47, 1331–1339.

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom: A survey of household resources and standards of living. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Van Schuur, W. H. (2003). Mokken scale analysis: Between the gutman scale and parametric itemresponse theory. Political Analysis, 11(2), 139–163.

Volacu, A., & Dumitru, A. (2019). Assessing non-intrinsic limitarianism. Philosophia, 47, 249–264.

WRR. (2014). Hoe Ongelijk is Nederland?. Den Haag: Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid.

Zwarthood, D. (2018). Autonomy-based reasons for limitarianism. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 21, 1181–1204.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank two anonymous referees for comments, and Bas van Bavel, Manuel Buitenhuis en Cok Vrooman for discussions of our research, and Colin Hickey for advice on the translation of the survey. In this paper, we make use of the data of the LISS (Longitudinal internet studies for the Social Sciences) panel administered by CentERData (Tilburg University, The Netherlands), and we gratefully acknowledge our collaboration on gathering the data.

Funding

The funding was provided by H2020 European Research Council (Grant No. 726153).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: English Translation of the Questionnaire

This survey is being conducted on behalf of Researchers from Utrecht University.

With this survey, the researchers want to establish at what point you think someone has enough money and possessions needed for a good life, and at what point you think someone has too much money. We are only interested in your opinion and not in what you believe others think. Hence, there are no wrong answers, because the only thing that matters is what you think

1.1 Question 1

We give you a description of the lives of 10 families. Each family consists of two parents (in their forties) and two children. For each family, we would like to know your judgement on how affluent they are. The information that is provided on savings/wealth includes all forms that personal wealth can take, hence besides savings also home equity, as well as expensive cars, collections of valuable items, investments, and so forth.

You can choose from 5 options:

-

Just enough This family has just enough to get by. They can never permit themselves any luxury.

-

Reasonable This family has enough to live on. They can afford some luxury now and then, but they would certainly lead a better life if they had some extra money.

-

Good This family is not lacking anything. They have a good life and can afford to do plenty of nice things, but they have to consider carefully before spending larger amounts on luxury.

-

Rich This family has more than they need to lead a good life. They rarely have to consider whether they can afford larger luxury spending.

-

Extremely rich This family has much more than they need to lead an affluent life. They never have to consider whether they can afford certain luxury spending, and even then, they still have plenty of money left to do extraordinary things that almost no one can afford. No one needs that much luxury.

Family A

- House:

-

Semi-detached/120 m2/RandstadFootnote 4/garden: 45 m2

- Second house:

-

No

- Car(s):

-

1 s-hand Ford Fiesta

- Holidays:

-

2 times a year: 1 week on a holiday-resort in the Netherlands, 2 weeks in the South of France

- Savings/wealth:

-

10,000 euro

How do you judge the standard of living of this family?

-

Just enough This family has just enough to get by

-

Reasonable This family can lead a reasonable life, but without luxury

-

Fine This family can lead a good life, with enough luxury

-

Rich This family has more than what is needed to live a good life, and amply enjoys luxury

-

Extremely rich No-one needs so much money and luxury.

Family B

- House:

-

Semi-detached/160 m2/Randstad/garden: 60 m2

- Second house:

-

No

- Car(s):

-

1 Volkswagen Passat

- Holidays:

-

2 times a year: 1 week on a holiday-resort in the Netherlands, 2 weeks in the South of France

- Savings/Wealth:

-

50,000 euro

How do you judge the standard of living of this family?

-

Just enough This family has just enough to get by

-

Reasonable This family can lead a reasonable life, but without luxury

-

Fine This family can lead a good life, with enough luxury

-

Rich This family has more than what is needed to live a good life, and amply enjoys luxury

-

Extremely rich A person does not need so much money and luxury.

Family C

- House:

-

Villa/230 m2/Randstad/Garden: 150 m2

- Second:

-

House: No

- Car(s):

-

1 Volkswagen Passat and 1 Audi A4

- Holidays:

-

3 times a year of which: 1 time winter holiday, one week Canary Islands and two weeks Thailand

- Savings/Wealth:

-

100,000 euro

How do you judge the standard of living of this family?

-

Just enough This family has just enough to get by

-

Reasonable This family can lead a reasonable life, but without luxury

-

Fine This family can lead a good life, with enough luxury

-

Rich This family has more than what is needed to live a good life, and amply enjoys luxury

-

Extremely rich No-one needs so much money and luxury.

Family D

- House:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/garden: 150 m2

- Second house:

-

Vacation home in the South of France

- Car(s):

-

1 Volkswagen Passat and 1 Audi A4

- Holiday(s):

-

3 times a year: 1 time a winter holiday, one week Canary Islands and two weeks Thailand

- Savings/Wealth:

-

150,000 euro

How do you judge the standard of living of this family?

-

Just enough This family has just enough to get by

-

Reasonable This family can lead a reasonable life, but without luxury

-

Fine This family can lead a good life, with enough luxury

-

Rich This family has more than what is needed to live a good life, and amply enjoys luxury

-

Extremely rich A person does not need so much money and luxury.

Family E

- House:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/garden: 300 m2/private pool

- Second house:

-

Vacation home in the South of France

- Car(s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz E-class and 1 Audi A4

- Holidays:

-

3 times a year: 1 time a winter holiday, one week Canary Islands and two weeks to Thailand

- Savings/Wealth:

-

200,000 euro

How do you judge the standard of living of this family?

-

Just enough This family has just enough to get by

-

Reasonable This family can lead a reasonable life, but without luxury

-

Fine This family can lead a good life, with enough luxury

-

Rich This family has more than what is needed to live a good life, and amply enjoys luxury

-

Extremely rich No-one needs so much money and luxury

Family F

- House:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/garden: 300 m2/private pool

- Second house:

-

Vacation home in the South of France

- Car(s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz E-class and 1 Audi A4

- Holidays:

-

Five times a year: 1 time a winter holidays, one week Canary Islands, twice to a European City, and two weeks to Thailand

- Savings/Wealth:

-

500,000 euro

How do you judge the standard of living of this family?

-

Just enough This family has just enough to get by

-

Reasonable This family can lead a reasonable life, but without luxury

-

Fine This family can lead a good life, with enough luxury

-

Rich This family has more than what is needed to live a good life, and amply enjoys luxury

-

Extremely rich No-one needs so much money and luxury

Family G

- House:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/garden: 500 m2/private pool

- Second house:

-

Vacation home in the South of France

- Car(s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz S-class en 1 Porsche

- Holidays:

-

Five times a year: 1 time a winter holidays, one week Canary Islands, twice to a European City, and two weeks to Thailand

- Savings/Wealth:

-

1 million euro

How do you judge the standard of living of this family?

-

Just enough This family has just enough to get by

-

Reasonable This family can lead a reasonable life, but without luxury

-

Fine This family can lead a good life, with enough luxury

-

Rich This family has more than what is needed to live a good life, and amply enjoys luxury

-

Extremely rich No-one needs so much money and luxury.

Family H

- House:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/garden: 500 m2/private pool

- Second house:

-

Vacation home in the South of France

- Car(s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz S-class and 1 Porsche

- Holidays:

-

Five times a year: 1 time a winter holidays, one week Canary Islands, twice to a European City, and two weeks to Thailand

- Savings/Wealth:

-

2.5 million euro

How do you judge the standard of living of this family?

-

Just enough This family has just enough to get by

-

Reasonable This family can lead a reasonable life, but without luxury

-

Fine This family can lead a good life, with enough luxury

-

Rich This family has more than what is needed to live a good life, and amply enjoys luxury

-

Extremely rich No-one needs so much money and luxury.

Family I

- House:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/garden: 800 m2/private pool

- Second House:

-

Vacation home in the South of France

- Car(s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz S-class and 1 Porsche

- Holidays:

-

Five times a year: 1 time a winter holidays, one week Canary Islands, twice to a European City, and two weeks to Thailand

- Savings/Wealth:

-

10 million euro

How do you judge the standard of living of this family?

-

Just enough This family has just enough to get by

-

Reasonable This family can lead a reasonable life, but without luxury

-

Fine This family can lead a good life, with enough luxury

-

Rich This family has more than what is needed to live a good life, and amply enjoys luxury

-

Extremely rich No-one needs so much money and luxury.

Family J

- Housing:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/garden: 1500 m2/private pool

- Second House:

-

Vacation home in the South of France

- Car(s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz S-class and 1 Porsche

- Holidays:

-

Five times a year: 1 time a winter holidays, one week Canary Islands, twice to a European City, and two weeks to Thailand

- Savings/Wealth:

-

70 million euro

How do you judge the standard of living of this family?

-

Just enough This family has just enough to get by

-

Reasonable This family can lead a reasonable life, but without luxury

-

Fine This family can lead a good life, with enough luxury

-

Rich This family has more than what is needed to live a good life, and amply enjoys luxury

-

Extremely rich No-one needs so much money and luxury.

1.2 Question 2

We would like to know your views on a number of societal issues such as wealth, inequality and taxation. It is not possible to give a wrong answer: we are only interested in your views, not in what you think other people believe.

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following claims?

Possible answers:

Fully disagree/disagree/neither agree, nor disagree/agree/fully agree.

-

It is not a problem if people become extremely rich, as long as they earn their money fairly according to the rules and do not evade tax.

-

The richest man in the world, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, is worth an estimated 98,000,000,000 dollars (98 billion dollars). It is undesirable for one person to have so much money.

-

In the Netherlands no-one should be allowed to earn more than the prime minister of our country; that is 157,287 euro gross per year.

-

There’s nothing wrong with major income inequalities as long as there is no discrimination in the labor market and the government ensures that everyone has access to high-quality education.

-

If the government Rutte III had to choose between cutting services for the most vulnerable people in society or increasing taxes on the income of the rich and superrich, they should choose a tax increase.

-

Dutch income-taxation consists of several tax brackets. The highest tax rate is 51.95%: this has to be paid over gross annual incomes above 68,507 euro. It would be better if there would be an additional tax rate of 70% for the part of the gross annual income above 150,000 euro.

-

The tax rates on income from labor, and the tax rate on profit (income from entrepreneurship) should be the same (for your information: the tax rates on profit are now lower than the tax rates on income from labor).

-

The government should not try to redistribute wealth.

-

Too much inequality is not good for society. Even if that inequality is not caused by tax-evasion, it is nevertheless better that no-one becomes superrich.

-

It is a problem if some people become superrich due to the fact that their parents leave them large fortunes via gifts or inheritances.

-

It is a problem for society if extremely rich people have more influence over politicians than people who are not rich.

-

If someone inherits a house with a value of 1 million euro, they pay about 183,730 euro inheritance taxation. If someone inherits an enterprise with a value of 1 million euro, they pay no inheritance taxation. It is unfair that there exist different tax-rates for those who inherit a company, compared with those inheriting a house, money, or other things.

1.3 Question 3: Open Questions

-

(1)

In the Netherlands, a single person is officially considered poor if he or she has less to spend than 971 euro per month. The average disposable monthly income per person is around 2100 euro. But many citizens have disposable monthly incomes that are much higher.

Do you think that a maximum or upper limit should be imposed on disposable monthly income per person in the Netherlands?

-

No

-

Yes, namely … euro per month

-

I don’t know

-

I don’t want to answer this question

-

-

(2)

Do you think that, within a company or organization, there should be a maximal difference between the wage of people who earn most, and those who earn least?

-

No

-

Yes, namely: the person who earns most can earn maximally …. times the wage of the person who earns least.

-

I don’t know

-

I don’t want to answer this question

-

-

(3)

Do you think that there should be an upper limit to how much savings anyone can have?

-

No

-

Yes, namely … euro.

-

I don’t know

-

I don’t want to answer this question

-

-

(4)

Do you think that there should be an upper limit for a person’s total wealth? This includes savings, stocks, one’s own company, valuable objects (such as art, one’s primary accommodation and dwellings that are rented out), land, and so forth.

-

No

-

Yes, namely … euro.

-

I don’t know

-

I don’t want to answer this question

-

-

(5)

Do you think there should be an upper limit to how much wealth (money, dwellings, stocks, companies, valuables, and so forth) that a person throughout their life can inherit from their parents (or from others)? This question concerns the total inheritance that a person receives from all the inheritances taken together.

-

No

-

Yes, namely … euro.

-

I don’t know

-

I don’t want to answer this question

-

Appendix 2: Original Dutch Version of the Questionnaire

Deze vragenlist wordt afgenomen in opdracht van onderzoekers aan de Universiteit Utrecht.

Met deze enquête willen de onderzoekers te weten komen wanneer u vindt dat iemand zoveel geld en spullen heeft dat die persoon een goed leven heeft, en wanneer u vindt dat iemand te veel geld heeft. Wij zijn alleen geïnteresseerd in uw mening en niet wat u denkt dat anderen vinden. U kunt dus ook geen fout antwoord geven, want het gaat er alleen maar om wat u denkt.

2.1 Vraag 1

Hieronder geven we een omschrijving van de levens van 10 gezinnen. Elk gezin bestaat uit twee ouders (veertigers) en twee kinderen. Voor elk gezin vragen we om uw oordeel te geven over hoe rijk dit gezin is. De informatie die we geven over hun spaargeld en vermogen omvat alle vormen waarin mensen vermogen kunnen verzamelen, dus ook het gedeelte van de waarde van het huis waar geen hypotheek op rust, kunstcollecties, aandelen, enzovoort.

U kan kiezen uit 5 opties:

-

1.

Net genoeg: dit gezin heeft net voldoende om rond te komen. Ze kunnen zich echter nooit enige luxe veroorloven.

-

2.

Redelijk: dit gezin heeft voldoende om rond te komen. Ze kunnen zich heel af en toe wat luxe veroorloven, maar zouden zeker een beter leven hebben als ze wat extra geld ter beschikking zouden hebben.

-

3.

Prima: Dit gezin heeft niets te kort. Ze hebben een goed leven en kunnen ruim voldoende leuke dingen doen, maar de echte luxe-uitgaven die ze willen doen moeten ze goed afwegen.

-

4.

Rijk: Dit gezin heeft meer dan het nodig heeft om een goed leven te leiden. Ze hoeven zelden na te denken of ze zich bepaalde luxe-uitgaven wel kunnen veroorloven.

-

5.

Superrijk: Dit gezin heeft veel meer dan nodig is om een welvarend leven te leiden. Ze hoeven nooit na te denken of ze bepaalde luxe-uitgaven kunnen doen en houden dan nog geld over om uitzonderlijke dingen te doen die bijna niemand zich kan permitteren.

Kan u voor onderstaande gezinnen zeggen of u vindt dat hun levensstandaard het beste omschreven kan worden als (1) net genoeg, (2) redelijk, (3) prima, (4) rijk, of (5) superrijk?

Gezin A

- Huis:

-

Twee-onder-een-kap/120 m2/Randstad/tuin: 45 m2

- Tweede huis:

-

Nee

- Auto(‘s):

-

1 tweedehands Ford Fiesta

- Vakantie:

-

2 keer per jaar waarvan: 1 keer een weekje vakantiepark in Nederland, 1 keer twee weken Zuid-Frankrijk

- Spaargeld/vermogen:

-

10.000 euro

Hoe beoordeelt u de levensstandaard van dit gezin?

-

1.

net genoeg dit gezin heeft net genoeg om rond te komen

-

2.

redelijk dit gezin kan een redelijk leven leiden, maar zonder luxe

-

3.

prima dit gezin kan een goed leven leiden, met voldoende luxe

-

4.

rijk dit gezin bezit meer dan wat nodig is om een goed leven te leiden, en geniet ruimschoots van luxe

-

5.

superrijk zoveel geld en luxe heeft een mens niet nodig.

Gezin B

- Huis:

-

Twee-onder-een-kap/160 m2/Randstad/tuin: 60 m2

- Tweede huis:

-

Nee

- Auto(‘s):

-

1 Volkswagen Passat

- Vakantie:

-

2 keer per jaar waarvan: 1 keer een weekje vakantiepark in Nederland, 1 keer twee weken Zuid-Frankrijk

- Spaargeld/vermogen:

-

50.000 euro

Hoe beoordeelt u de levensstandaard van dit gezin?

-

1.

net genoeg dit gezin heeft net genoeg om rond te komen

-

2.

redelijk dit gezin kan een redelijk leven leiden, maar zonder luxe

-

3.

prima dit gezin kan een goed leven leiden, met voldoende luxe

-

4.

rijk dit gezin bezit meer dan wat nodig is om een goed leven te leiden, en geniet ruimschoots van luxe

-

5.

superrijk zoveel geld en luxe heeft een mens niet nodig.

Gezin C

- Huis:

-

Villa/230 m2/Randstad/Tuin: 150 m2

- Tweede huis:

-

Nee

- Auto(‘s):

-

1 Volkswagen Passat en 1 Audi A4

- Vakantie:

-

3 keer per jaar waarvan: 1 keer wintervakantie, een week Canarische eilanden en twee weken Thailand

- Spaargeld/vermogen:

-

100.000 euro

Hoe beoordeelt u de levensstandaard van dit gezin?

-

1.

net genoeg dit gezin heeft net genoeg om rond te komen

-

2.

redelijk dit gezin kan een redelijk leven leiden, maar zonder luxe

-

3.

prima dit gezin kan een goed leven leiden, met voldoende luxe

-

4.

rijk dit gezin bezit meer dan wat nodig is om een goed leven te leiden, en geniet ruimschoots van luxe

-

5.

superrijk zoveel geld en luxe heeft een mens niet nodig.

Gezin D

- Huis:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/Tuin: 150 m2/privé-zwembad

- Tweede huis:

-

Buitenverblijf in Zuid-Frankrijk

- Auto(‘s):

-

1 Volkswagen Passat en 1 Audi A4

- Vakantie:

-

3 keer per jaar waarvan: 1 keer wintervakantie, 1 keer Canarische eilanden en 2 weken Thailand

- Spaargeld/vermogen:

-

100.000 euro

Hoe beoordeelt u de levensstandaard van dit gezin?

-

1.

net genoeg dit gezin heeft net genoeg om rond te komen

-

2.

redelijk dit gezin kan een redelijk leven leiden, maar zonder luxe

-

3.

prima dit gezin kan een goed leven leiden, met voldoende luxe

-

4.

rijk dit gezin bezit meer dan wat nodig is om een goed leven te leiden, en geniet ruimschoots van luxe

-

5.

superrijk zoveel geld en luxe heeft een mens niet nodig.

Gezin E

- Huis:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/Tuin: 300 m2/privé-zwembad

- Tweede huis:

-

Buitenverblijf in Zuid-Frankrijk

- Auto(‘s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz E-klasse en 1 Audi A4

- Vakantie:

-

3 keer per jaar waarvan: 1 keer wintervakantie, 1 keer Canarische eilanden en 1 grote reis naar land van keuze

- Spaargeld/vermogen:

-

150.000 euro

Hoe beoordeelt u de levensstandaard van dit gezin?

-

1.

net genoeg dit gezin heeft net genoeg om rond te komen

-

2.

redelijk dit gezin kan een redelijk leven leiden, maar zonder luxe

-

3.

prima dit gezin kan een goed leven leiden, met voldoende luxe

-

4.

rijk dit gezin bezit meer dan wat nodig is om een goed leven te leiden, en geniet ruimschoots van luxe

-

5.

superrijk zoveel geld en luxe heeft een mens niet nodig.

Gezin F

- Huis:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/Tuin: 300 m2/privé-zwembad

- Tweede huis:

-

Buitenverblijf in Zuid-Frankrijk

- Auto(‘s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz E-klasse en 1 Audi A4

- Vakantie:

-

5 keer per jaar waarvan: 1 keer wintervakantie, 1 week Canarische eilanden, 2 keer een week naar een Europese stad, en 1 keer twee weken naar Thailand

- Spaargeld/vermogen:

-

200.000 euro

Hoe beoordeelt u de levensstandaard van dit gezin?

-

1.

net genoeg dit gezin heeft net genoeg om rond te komen

-

2.

redelijk dit gezin kan een redelijk leven leiden, maar zonder luxe

-

3.

prima dit gezin kan een goed leven leiden, met voldoende luxe

-

4.

rijk dit gezin bezit meer dan wat nodig is om een goed leven te leiden, en geniet ruimschoots van luxe

-

5.

superrijk zoveel geld en luxe heeft een mens niet nodig.

Gezin G

- Huis:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/Tuin: 300 m2/privé-zwembad

- Tweede huis:

-

Buitenverblijf in Zuid-Frankrijk

- Auto(‘s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz S-klasse en 1 Porsche

- Vakantie:

-

5 keer per jaar waarvan: 1 keer wintervakantie, 1 week Canarische eilanden, 2 keer een week naar een Europese stad, en 1 keer twee weken naar Thailand

- Spaargeld/vermogen:

-

1 miljoen euro

Hoe beoordeelt u de levensstandaard van dit gezin?

-

1.

net genoeg dit gezin heeft net genoeg om rond te komen

-

2.

redelijk dit gezin kan een redelijk leven leiden, maar zonder luxe

-

3.

prima dit gezin kan een goed leven leiden, met voldoende luxe

-

4.

rijk dit gezin bezit meer dan wat nodig is om een goed leven te leiden, en geniet ruimschoots van luxe

-

5.

superrijk zoveel geld en luxe heeft een mens niet nodig.

Gezin H

- Huis:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/Tuin: 300 m2/privé-zwembad

- Tweede huis:

-

Buitenverblijf in Zuid-Frankrijk

- Auto(‘s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz S-klasse en 1 Porsche

- Vakantie:

-

5 keer per jaar waarvan: 1 keer wintervakantie, 1 week Canarische eilanden, 2 keer een week naar een Europese stad, en 1 keer twee weken naar Thailand

- Spaargeld/vermogen:

-

2,5 miljoen euro

Hoe beoordeelt u de levensstandaard van dit gezin?

-

1.

net genoeg dit gezin heeft net genoeg om rond te komen

-

2.

redelijk dit gezin kan een redelijk leven leiden, maar zonder luxe

-

3.

prima dit gezin kan een goed leven leiden, met voldoende luxe

-

4.

rijk dit gezin bezit meer dan wat nodig is om een goed leven te leiden, en geniet ruimschoots van luxe

-

5.

superrijk zoveel geld en luxe heeft een mens niet nodig.

Gezin I

- Huis:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/Tuin: 300 m2/privé-zwembad

- Tweede huis:

-

Buitenverblijf in Zuid-Frankrijk

- Auto(‘s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz S-klasse en 1 Porsche

- Vakantie:

-

5 keer per jaar waarvan: 1 keer wintervakantie, 1 week Canarische eilanden, 2 keer een week naar een Europese stad, en 1 keer twee weken naar Thailand

- Spaargeld/vermogen:

-

10 miljoen euro

Hoe beoordeelt u de levensstandaard van dit gezin?

-

1.

net genoeg dit gezin heeft net genoeg om rond te komen

-

2.

redelijk dit gezin kan een redelijk leven leiden, maar zonder luxe

-

3.

prima dit gezin kan een goed leven leiden, met voldoende luxe

-

4.

rijk dit gezin bezit meer dan wat nodig is om een goed leven te leiden, en geniet ruimschoots van luxe

-

5.

superrijk zoveel geld en luxe heeft een mens niet nodig.

Gezin J

- Huis:

-

Villa/300 m2/Randstad/Tuin: 300 m2/privé-zwembad

- Tweede huis:

-

Buitenverblijf in Zuid-Frankrijk

- Auto(‘s):

-

1 Mercedes-Benz S-klasse en 1 Porsche

- Vakantie:

-

5 keer per jaar waarvan: 1 keer wintervakantie, 1 week Canarische eilanden, 2 keer een week naar een Europese stad, en 1 keer twee weken naar Thailand

- Spaargeld/vermogen:

-

70 miljoen euro

Hoe beoordeelt u de levensstandaard van dit gezin?

-

1.

net genoeg dit gezin heeft net genoeg om rond te komen

-

2.

redelijk dit gezin kan een redelijk leven leiden, maar zonder luxe

-

3.

prima dit gezin kan een goed leven leiden, met voldoende luxe

-

4.

rijk dit gezin bezit meer dan wat nodig is om een goed leven te leiden, en geniet ruimschoots van luxe

-

5.

superrijk zoveel geld en luxe heeft een mens niet nodig.

2.2 Vraag 2

Wij zouden ook graag uw mening weten over een aantal maatschappelijke kwesties over rijkdom, ongelijkheid, en belastingen. U kunt geen fout antwoord geven: wij zijn alleen geïnteresseerd in uw mening, niet in wat u denkt dat andere mensen vinden.

In hoeverre bent u het eens of niet eens met onderstaande stellingen?

Antwoord op een schaal van 1 tot 5, als volgt:

1 = zeer eens

2 = eens

3 = niet eens, niet oneens

4 = oneens

5 = zeer oneens

-

Zolang mensen hun geld op een eerlijke manier verdiend hebben en niet aan belastingontduiking doen, is het geen probleem als ze superrijk worden.

-

De rijkste man ter wereld, Jeff Bezos (de oprichter van Amazon) heeft een geschat vermogen van 98.000.000.000 dollar (98 miljard dollar). Het is onwenselijk dat één persoon zoveel geld heeft.

-

Niemand zou meer mogen verdienen dan de minister-president van ons land, namelijk 157.287 Euro bruto per jaar.

-

Grote inkomensongelijkheid is niet erg zolang er geen discriminatie is op de arbeidsmarkt en de overheid zorgt voor onderwijs van goede kwaliteit voor iedereen.

-

Als de regering Rutte III moet kiezen tussen versoberen van de voorzieningen voor de meest kwetsbare medeburgers of het verhogen van de belastingen op de inkomens van de rijken en superrijken, dan moet ze voor belastingverhoging kiezen.

-

De Nederlandse inkomensbelasting kent verschillende belastingtarieven. Het hoogste belastingtarief, is 51,95%: dit moet betaald worden over het bruto-jaarinkomen dat hoger is dan 68.507 Euro. Het zou beter zijn als er nog een extra belastingtarief van 70% zou ingevoerd worden, bijvoorbeeld voor het gedeelte van het brutojaarinkomen dat hoger is dan 150.000 Euro.

-

De belastingentarieven op inkomen uit arbeid, en de belastingtarieven op winst (inkomen uit bedrijvigheid) zouden even hoog moeten zijn.

-

De overheid moet zo weinig mogelijk proberen rijkdom te herverdelen om de mensen die slechter af zijn financieel te helpen.

-

Te grote ongelijkheid is niet goed voor de samenleving, zelfs als die gelijkheid ontstaat zonder dat mensen aan belastingontduiking doen, is het toch beter als ze niet superrijk worden, omdat te grote ongelijkheid niet goed is voor de samenleving.

-

Het is een probleem als sommige mensen rijk worden enkel vanwege het feit dat hun ouders rijk zijn en deze ouders via schenkingen of erfenissen grote vermogens overdragen aan hun kinderen.

-

Het is een maatschappelijk probleem als superrijke mensen veel meer politieke macht hebben dan mensen die niet rijk zijn.

-

Wie een huis erft ter waarde van 1 miljoen Euro, betaalt ongeveer 183.730 euro erfbelasting. Wie een bedrijf erft ter waarde van 1 miljoen Euro, betaalt geen erfbelasting. Het is oneerlijk dat het overerven van bedrijven veel minder zwaar belast wordt dan het overerven van geld, woningen of andere dingen.

2.3 Vraag 3: Open Vragen

-

(1)

In Nederland is iemand arm als hij minder dan 971 Euro per maand te besteden heeft. Het gemiddelde besteedbare maand inkomen per persoon is ongeveer 2000 euro. (cijfers voor 2014).

Maar veel landgenoten hebben een besteedbaar maandelijks inkomen dat veel hoger ligt.

Vindt u dat er een maximum of bovengrens zou moeten zijn aan het besteedbaar maandelijkse inkomen per persoon in Nederland?

-

Neen

-

Ja, namelijk… euro per maand

-

Ik wil/kan deze vraag niet beantwoorden

-

-

(2)

Vindt u dat er binnen een bedrijf of organisatie een maximale verhouding zou moeten zijn tussen het salaris van de mensen die het meeste verdienen en de mensen die het minst verdienen in dat bedrijf of in die organisatie?

-

Neen

-

Ja, namelijk: diegene die het meeste verdient mag maximaal …. keer het salaris verdienen van diegene die het minste verdient.

-

Ik wil/kan deze vraag niet beantwoorden

-

-

(3)

Vindt u dat er een bovengrens zou moeten zitten aan hoeveel liquide vermogen (spaargeld) iemand zou mogen bezitten?

-

Neen

-

Ja, namelijk … euro.

-

Ik wil/kan deze vraag niet beantwoorden

-

-

(4)

Vindt u dat er een bovengrens zou moeten zitten aan de hoeveelheid totale vermogen (spaargeld, aandelen, eigen bedrijf, waardevolle objecten zoals kunst, hoofdwoning en woningen die verhuurt worden, etc., gronden, etc.) dat iemand zou mogen bezitten?

-

Neen

-

Ja, namelijk … euro.

-

Ik wil/kan deze vraag niet beantwoorden

-

-

(5)

Vindt u dat er een bovengrens zou moeten zitten aan de hoeveelheid vermogen (geld, woningen, aandelen, bedrijven, waardevolle objecten etc.) dat iemand in zijn leven kan erven van zijn ouders of andere erflaters? Het gaat dus om het totale bedrag dat iemand ontvangt uit alle erfenissen tezamen.

-

Neen

-

Ja, namelijk … euro.

-

Ik wil/kan deze vraag niet beantwoorden

-

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Robeyns, I., Buskens, V., van de Rijt, A. et al. How Rich is Too Rich? Measuring the Riches Line. Soc Indic Res 154, 115–143 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02552-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02552-z