Abstract

This study focuses on the long-term trend in happiness by income level in the United States. General Social Survey data suggest that in the past, rich and poor Americans were not only more equal in terms of income, but also in terms of their subjective wellbeing: the happiness gap between the poor and the rich has been increasing. Today’s poor suffer greater relative unhappiness than the poor of past decades. The gap between the poor and the rich is substantial, approximately 0.4 on a 1–3 happiness scale. The increase in the happiness gap is striking: comparing the 1970s to the 2000s, the gap has widened by about 40 % between the poor and the rich, and by about 50 % between the middle class and the rich.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use the terms subjective wellbeing and happiness interchangeably. Happiness, life satisfaction, and subjective wellbeing do overlap. Although they are to some degree distinct, in the happiness literature it is customary to treat these concepts interchangeably (see e.g., Veenhoven 2008; Frey and Stutzer 2002; Diener and Lucas 1999; Radcliff 2013).

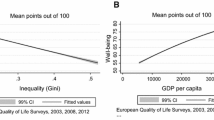

There was a lively discussion between Veenhoven and Delhey, and it resulted in many papers (http://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=veenhoven+delhey+inequality). This debate, however, is beyond the scope of this article, which deals with the US and changes over time, not cross-sectional comparisons across countries. The results of the present study do not necessarily conflict with Berg and Veenhoven (2010), who found that across nations there is no correlation between income inequality and average happiness. It is even possible that income inequality can add to average happiness in many countries by increasing the pie, though probably not anymore in the US—some economists think that current levels of inequality in the US are bad for the economy. Income inequality can actually hurt the economy, not only society (The Economist 2012a, b, 2013). Stevenson and Wolfers (2008) found happiness inequality to be decreasing, but they did not establish a connection with income inequality. Easterlin (2001) focused on happiness by income, but only at one point in time. Blanchflower and Oswald (2004) looked at change over time, but at the effect of income on happiness, not on the effect of income inequality on happiness inequality.

General reduction of inequality in happiness or reduction between some two groups, say racial groups, can co-exist with increasing inequality in the happiness across income groups. Taking Using a public health analogy, the life expectancy gap between Blacks and Whites has decreased but the life expectancy gap between the educated and the uneducated has increased (Meara et al. 2008).

We are grateful for this suggestion to an anonymous reviewer who pointed out a need: “to find a convincing way of handling trends other than the increase in inequality, which may be causing changes in the level and distribution of happiness.”

However, the Easterlin Paradox is observed in many countries, and our explanation may not hold up across the board—we are grateful for this point to Richard Easterlin.

References

Alesina, A., Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2009–2042.

Attanasio, O., Hurst, E., & Pistaferri, L. (2012). The Evolution of Income, Consumption, and Leisure inequality in the US, 1980–2010. Tech. rep., National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bartal, I., Decety, J., & Mason, P. (2011). Empathy and pro-social behavior in rats. Science, 334, 1427–1430.

Berg, M., & Veenhoven, R. (2010). Income inequality and happiness in 119 nations. repub.eur.nl.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., Fischer, J. A., Schnellenbach, J., & Gehring, K. (2013). Inequality and happiness: When perceived social mobility and economic reality do not match. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 91, 75–92.

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (2003). Does inequality reduce happiness? Evidence from the states of the USA from the 1970s to the 1990s. Mimeographed, Warwick University.

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2011). International happiness: A new view on the measure of performance. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 25, 6–22.

Bok, D. (2010). The politics of happiness: What government can learn from the new research on well-being. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brickman, P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Buman, R. (1978). Lottery winners and accident victims: Is happiness relative? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 917–927.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cassidy, J. (2013). American inequality in six charts. New York: The New Yorker.

Chokshi, N. (2009). Education costs rising faster than health care. Washington: The Atlantic.

Davis, J. A. (1966). The campus as a frog pond: An application of the theory of relative deprivation to career decisions of college men. American Journal of Sociology, 72, 17–31.

Davis, J. A., Smith, T. W., & Marsden, P. V. (2007): General Social Surveys, 1972–2006 [Cumulative File], Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Delhey, J., & Dragolov, G. (2014). Why inequality makes Europeans less happy: The role of distrust, status anxiety, and perceived conflict. European Sociological Review, 30, 151–165.

Delhey, J., & Kohler, U. (2010). Is happiness inequality immune to income inequality? New evidence through instrument-effect-corrected standard deviations. Social Science Research, 40(3), 742–756.

Delhey, J., & Urlich, K. (2006). From nationally bounded to Pan-European inequalities? On the importance of foreign countries as reference groups. European Sociological Review, 22, 125–140.

Desmond, M. (2015). Severe deprivation in America: An introduction. RSF 1(2):1–11. http://www.rsfjournal.org/doi/full/10.7758/RSF.2015.1.2.01. Retrieved 12 Jan 2016.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. R. (1999). Personality and subjective well-being. In E. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 213–229). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., & Lucas, R. E. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz (Vol. 89, pp. 98–125). New York: Academic Press Inc.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. The Economic Journal, 111, 465–484.

Easterlin, R. A., McVey, L. A., Switek, M., Sawangfa, O., & Zweig, J. S. (2010). The happiness–income paradox revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 22463–22468.

Easterlin, R. A., Morgan, R., Switek, M., & Wang, F. (2012). China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 9775–9780.

Edelman, P. (2012). So rich, so poor: Why it’s so hard to end poverty in America. New York: The New Press.

Edin, K. J., & Shaefer, H. L. (2015). $2.00 a Day: Living on almost nothing in America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Fischer, C. S. (2008). What wealth-happiness paradox? A short note on the American case. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 219–226.

Fischer, C. S. (2010). Made in America: A social history of American culture and character. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Frank, R. H. (2010). Hey, big spender: You need a surtax. New York: New York Times.

Frank, R. (2012). The Darwin economy: Liberty, competition, and the common good. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Frank, R. H. (2014). The vicious circle of income inequality. New York: New York Times.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic literature, 40(2), 402–435.

Gilbert, D. L. (2011). The American class structure in an age of growing inequality (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Gould, E., & Davis, A. (2015). Persistent poverty’s largest cause is inequality, not family structure. August 10. https://thesocietypages.org/families/2015/08/10/poverty-caused-by-inequality-not-family-structure/. Retrieved 17 Feb 2015.

Graham, C., & Felton, A. (2006). Inequality and happiness: Insights from Latin America. Journal of Economic Inequality, 4, 107–122.

Helliwell, J., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2012). World happiness report. New York: The Earth Institute, Columbia University.

Hout, M. (2004). Getting the most out of the GSS income measures. Washington: National Opinion Research Center.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291.

Ligon, E. ([1989] 1994). The development and use of a consistent income measure for the General Social Survey. National Opinion Research Center, The University of Chicago

Massey, Douglas S. (2007). Categorically unequal: The American stratification system. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Meara, E. R., Richards, S., & Cutler, D. M. (2008). The gap gets bigger: changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981–2000. Health Affairs, 27, 350–360.

Michalos, A. (1985). Multiple discrepancies theory (MDT). Social Indicators Research, 16, 347–413.

Myers, D. G. (2004). Exploring psychology. London: Macmillan.

Ng, Y.-K. (1997). A case for happiness, cardinalism, and interpersonal comparability. The Economic Journal, 107, 1848–1858.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2006). Conversations with History: Martha Nussbaum. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qy3YTzYjut4&list=PLDmIbYyjfK8BAq8q-ZYzakLXnGtQ8PS0I&index=147.

O’Connell, M. (2004). Fairly satisfied: Economic equality, wealth and satisfaction. Journal of Economic Psychology, 25, 297–305.

Oishi, S., Kesebir, S., & Diener, E. (2011). Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science, 22, 1095–1100.

Oishi, S., Schimmack, U., & Diener, E. (2012). Progressive taxation and the subjective well-being of nations. Psychological Science, 23, 86–92.

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A., Holmes IV, O., & Avery, D. R. (2014). The subjective well-being political paradox: Happy welfare states and unhappy liberals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(6), 1300–1308.

Oshio, T., & Kobayashi, M. (2010). Income inequality, perceived happiness, and self-rated health: Evidence from nationwide surveys in Japan. Social Science and Medicine, 70, 1358–1366.

Oshio, T., & Kobayashi, M. (2011). Area-level income inequality and individual happiness: Evidence from Japan. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 633–649.

Pickett, K. E. & Wilkinson, R. G. (2014). Income inequality and health: A causal review. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 316–326.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the 21st century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Putnam, R. D. (2001). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Putnam, Robert D. (2015). Our kids: The American dream in crisis. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Radcliff, B. (2013). The political economy of human happiness: How voters’ choices determine the quality of life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schulz, W. (1995). Multiple-discrepancies theory versus resource theory. Social Indicators Research, 34, 153–169.

Sen, A. (2000). Development as freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

Shaefer, H. L., Edin, K., & Talbert, E. (2015). Understanding the dynamics of $2-a-day poverty in the United States. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 1(1):120–38. http://www.rsfjournal.org/doi/full/10.7758/RSF.2015.1.1.0. Retrieved 12 Jan 2016.

Snowdon, C. (2010). The spirit level delusion: Fact-checking the left’s new theory of everything. Ripon: Little Dice.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Happiness inequality in the United States. Tech. rep., National Bureau of Economic Research.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2009). The paradox of declining female happiness. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 1, 190–225.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2012). The price of inequality: How today’s divided society endangers our future. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2013). Student debt and the crushing of the American dream. New York: The New York Times.

Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. (2009). Report by the Commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr.

The Economist. (2011). The rich and the rest What to do (and not do) about inequality. Economist.

The Economist. (2012a). For richer, for poorer. The Economist.

The Economist. (2012b). True progressivism. The Economist.

The Economist. (2013). Having your cake; Less inequality does not need to mean less efficiency. The Economist.

Tricomi, E., Rangel, A., Camerer, C., & O’Doherty, J. (2010). Neural evidence for inequality-averse social preferences. Nature, 463, 1089–1091.

Veenhoven, R. (2005). Return of inequality in modern society? Test by dispersion of life-satisfaction across time and nations. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 457–487.

Veenhoven, R. (2008). Sociological theories of subjective well-being. In M. Eid & R. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being: A tribute to ed Diener (pp. 44–61). New York: The Guilford Press.

Veenhoven, R., & Ehrhardt, J. (1995). The cross-national pattern of happiness: Test of predictions implied in three theories of happiness. Social Indicators Research, 34, 33–68.

Veenhoven, R., & Vergunst, F. (2013). The Easterlin illusion: economic growth does go with greater happiness. Munich Personal RePEc Archive, Paper No. 43983.

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. E. (2006). Income inequality and population health: A review and explanation of the evidence. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 1768–1784.

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. E. (2010). The spirit level: Why equality is better for everyone. London: Penguin.

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (2010). Does inequality harm the middle class? Kyklos, 63, 301–316.

Wynne, C. (2004). Animal behaviour: Fair refusal by capuchin monkeys. Nature, 428, 140–140.

Yellen, J. (2006). Economic inequality in the United States. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF) Economic Letter, 2006-33-34 (December 1, 2006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank Ruut Veenhoven. We take full responsibility for any errors or weaknesses that remain.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Additional Descriptive Statistics

See Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6 and Tables 3, 4, 5.

Happiness by deciles of income. Results are similar to those in Fig. 5: happiness is stable for the rich and declining for the poor

Appendix 2: Other Variables by Income Quintiles Over Time

Generalized trust: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” The higher the value, the more trust. There is little difference by income, but a very clear pattern in the overall trend exists as documented by many others (e.g., Putnam 2001): Americans report lower trust than in the past

Support for government action to reduce income differences. The higher the value, the greater the support. Numbers 1–5 shown at the right side of the graph denote income quintiles. As expected, the poorer the group, the more support there is for reducing income differences. Yet, the biggest increase in favor of redistribution is among the richest

Opinions about fairness. The higher the value, the more agreement that “people try to take advantage of you as opposed to be fair.” Along with the increasing income gap, there was an increase amongst the poorest in the opinion that people are taken advantage of. Numbers 1–5 shown at the right side of the graph denote income quintiles

Appendix 3: Happiness by Original Income Measures

See Fig. 10.

Happiness by original income measures. 95 % CI shown. The top row shows the two earliest income measures (gss names: income72 and income77). The bottom row shows the latest income measures (gss names: income98 and income06). Vertical lines are drawn to aid interpretation. In all years happiness for the richest is approximately 2.4. But there is a change for the poorest: in the 1970s it was approximately 2.0, but in the last decade it was below 2.0 (about 1.9). There are also some interesting irregularities: for instance, the least happy are not the poorest

Appendix 4: Comparison of Inequality Measures from GSS and from Census

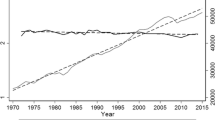

Gini data from the Census Bureau come from Table F-4 “Gini Indexes for Families, by Race and Hispanic Origin of Householder: 1947 to 2014,” available at https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/inequality. Note that this gini index is for families (in this paper we use family income from the GSS). Furthermore, it is worth noting that from 1947 until 1972, when the GSS series began, the gini decreased only slightly and reached a low of 0.348 in 1968 before increasing, through to the present day. Data are plotted in graph 1. The correlation between the two series is 0.85. There is a spike in the GSS gini, another reason to rerun the analyses without the post-recession years. Yet, both series show a virtually identical linear trend as shown by fitted values (Fig. 11).

Data on income quintiles from the GSS and the Census are shown in Figs. 12 and 13. The Census data use 2011 constant dollars. The GSS uses 1986 constant dollars. The quintiles are more uneven for the GSS series. Incomes are estimates in the GSS and, for many years, not very continuous but rather, are presented more discretely. This limitation is unfortunate, particularly because these are the only data available that are consistent series and go back as far in time. The series are especially inconsistent in earlier years when there were fewer income categories, and so the cutoff points for quantiles are coarser. The fit between the two series is not close; to check whether the results might have been due to quantization, we reran the analyses using 3 and 7 classes (see “Appendix 5”). Results are similar.

Upper limits for family income fifths. 2011 CPI-U-RS adjusted dollars. Source: US Census Bureau, Table F1, see the link for data footnotes: http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/families

Appendix 5: Robustness Checks: Using 3 and 7 Classes

Stata (the statistical software used in this study) performs quantization (assigns variable values into quantiles) in a peculiar way by checking whether it passes the appropriate percentile for given quantile and if it does not, it uses the lower quantile for categorization. This yields non-optimal cutoff points when a variable has few levels. For instance, in 1972 real income has the following distribution:

Income | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|

2707 | 123 | 8.34 | 8.34 |

8122 | 165 | 11.19 | 19.54 |

13,537 | 160 | 10.85 | 30.39 |

18,951 | 160 | 10.85 | 41.25 |

24,366 | 192 | 13.03 | 54.27 |

30,458 | 217 | 14.72 | 69 |

37,226 | 159 | 10.79 | 79.78 |

43,994 | 103 | 6.99 | 86.77 |

50,763 | 63 | 4.27 | 91.04 |

60,915 | 67 | 4.55 | 95.59 |

74,452 | 33 | 2.24 | 97.83 |

109,355 | 32 | 2.17 | 100 |

Total | 1474 | 100 |

Hence, an optimal solution is to classify only the first two categories (2707, 8122) into the first quintile (they constitute 19.54 percent of the distribution), but Stata takes the third category as well (13,573), because it does not reach 20 % after taking the first two. This peculiar approach has been documented on the Stata listserv by Stata’s foremost expert Nick Cox http://www.stata.com/statalist/archive/2012-06/msg01193.html, and at http://www.stata.com/statalist/archive/2012-06/msg01187.html. An obvious question is what if the study’s result—that the poor and rich are more unequal in happiness—is due to this strange clustering? We use 3 and 7 bins as a robustness check. Results hold up as shown in Tables 6 and 7.

Appendix 6: Family Income Versus Personal Income

There are theoretical and technical reasons for using family income as opposed to individual income, but for robustness, we discuss here the results using personal income. With respect to family income reported here there is a rather smooth gradient: the richer the group, the smaller the decrease in happiness over time, and as a result the bigger the gap in happiness. With respect to respondents’ income, this is still true when comparing the first quintile to the others: the poorest people became less happy over time. Richer groups remained more flat in their happiness, so the happiness gap between the poorest and the rest has increased. The key difference in results when using personal income is that all richer income groups remained at about the same happiness levels over time, so whatever happiness differences there were in the 1970s, they remained after the 2000s. In addition, the very richest group became slightly less happy, though not nearly by as much as the poorest group. The three middle quintiles remained most stable over time. For the reasons mentioned above, family income is a better measure, and we base our overall conclusions on the family income variable. These results do not generalize entirely when using personal income. In particular, the happiness gap between the richest and middle class has not increased if individual income is used instead of family income.

Finally, we reran models using family income divided by the natural log of the number of people in the household +1 (to avoid zero from ln(1)). The effect of family income on happiness depends in part on the number of people in a household. The rationale for dividing family income by the natural log of the number of people in a household is to scale the effect to reflect the diminishing marginal effect of each additional member of a household on family income (the addition of each subsequent member of a household “costs” less).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A., Mazelis, J.M. More Unequal in Income, More Unequal in Wellbeing. Soc Indic Res 132, 953–975 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1327-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1327-0