Abstract

Individual prosperity and welfare can be measured using both objective and subjective criteria. Although theory and previous research suggest that these two methods can produce corresponding results, the measurements can also be inconsistent. Against this background, the current paper investigates the relationship between the objective income position of older Europeans (aged 50 + years) and their perception of their financial situation, using the seventh wave of the Survey of Health, Aging, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) conducted in 2017. The main research questions include (1) how is objective income distributed in old age across Europe?, (2) how do elderly Europeans evaluate their income situation subjectively?, (3) is there a discrepancy between the objective prosperity position and their subjective perception observable?, (4) are there country-specific differences that are observable?, and (5) how can such discrepancies be explained?

The results show that objective income positions can be congruent with subjective self-perceptions, both good (well-being) and bad (deprivation), of one’s income situation. However, this is not always the case, and country-specific variations do exist. In analyzing the causes of the 2 forms of nonconformance—namely, adaptation (satisfaction paradox) and dissonance (dissatisfaction dilemma)—this paper concludes that sociodemographic and socioeconomic determinants alone cannot account for discrepancies. The consideration of certain social-psychological influences or personality traits and especially social comparison processes (namely, with one’s past) is essential in explaining both the satisfaction paradox and the dissatisfaction dilemma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Increasing poverty and inequality continue to be prominent features of modern societies and key issues within social science research. The extent and structure differ strongly depending on the theoretical and empirical assumptions made by the researchers, which can be attributed to differences in the operationalization and in the methods of measurement”. Further complicating the matter is the fact that in social science research, individual prosperity can be measured in several ways. In addition to objective criteria, subjective aspects of the empirical distribution of resources—such as income or assets—must often be taken into consideration. Subjective criteria can involve individuals’ self-perceptions of their wealth and welfare as well as any feelings of being disadvantaged. Indeed, individual well-being is influenced by far more than economics. From a broader point of view, subjective well-being depends in general upon various subjective criteria like perceived values, individual preferences, (life) satisfaction or the general quality of life (see for example Zapf 1979a, and for different concepts in general Hagerty et al. 2001).

Objective and subjective measurements of well-being can correspond or be inconsistent. In this vein, Zapf’s typology of welfare positions (which will be discussed in greater detail below) combines objective living conditions with subjective dimensions of well-being and distinguishes four categories for welfare. The consistent positions are characterized by either well-being (if good objective living conditions and a good subjective evaluation correspond) or deprivation (if unfavorable objective conditions are evaluated as such). Individuals with inconsistent welfare positions can be either subjectively satisfied with objectively unsatisfying living conditions or unsatisfied even though their living conditions are good. The former situation is characterized by adaptation, a phenomenon referred as the satisfaction paradox. The experience of the latter group has been described as dissonance, or the dissatisfaction dilemma.

Against this background, the paper presents findings regarding the relationship between objective income positions and their subjective evaluation in a specific vulnerable population group: older people. Drawing on data from the seventh wave of the Survey of Health, Aging, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) in 2017, our study analyzed the possible causes of inconsistent welfare positions among the older European population (aged 50 + years) in 26 countries. As older people are an expanding population group in contemporary societies, it seems beneficial to focus on the objective and subjective well-being of this age group. Older populations are also marked by specific vulnerabilities that make them a compelling subject for study. Several challenges during old age can affect an individual’s life satisfaction and well-being. Examples include losing independence because of physical or cognitive impairments, experiencing health challenges, losing close relationships through the death of a spouse or partner, or facing relocation to new contexts (see Hansen and Slagsvold 2012; Donisi et al. 2020; Lara et al. 2020; Smith et al. 2002).

Surprisingly, previous research on the well-being of different age groups reveals a paradox of higher subjective well-being in older age groups even though the objective quality of life is often lower (see, for example, Steptoe, Deaton and Stone 2014). In light of this, the specific research questions of the manuscript are as follows: (1) how is objective income distributed in old age across Europe?, (2) how do elderly Europeans evaluate their income situation subjectively?, (3) is there a discrepancy between the objective prosperity position and their subjective perception observable?, (4) are there country-specific differences that are observable?, and (5) how can such discrepancies be explained?

2 Background (Theoretical)

The question when somebody can be regarded as poor or rich is an important sociological topic and shaped the research scene for several decades. As there are different criteria available to determine an individual’s welfare position, ranging from various objective indicators to several subjective measurements, the extent of poverty and inequality as well as the consternation can differ strongly (for an overview of related concepts, see, for example, Hagenaars and Vos 1988). For objective criteria, poverty can be defined and measured either directly in terms of consumption or indirectly in terms of income (see Ringen 1988). While the concept of relative deprivation directly takes into account a visible lack of resources and the associated low level of consumption, the indirect method measures according to income poverty lines. In contrast, subjective criteria take into account a self-evaluation of the economic situation and consider, for example, the minimum income required to make ends meet in a given area. Another approach regarding subjective poverty is to ask the family heads what they consider to be the minimum income level for their own family (for further subjective concepts, see, in detail, Flik and van Praag 1991).

However, how can differences between the objective income position on one hand and the perceived situation on the other hand be displayed? According to Zapf (1984), the combination of individual objective income positions and their subjective evaluations results in four possible categories of welfare positions (see Table 1). The positions are classified as consistent if both measurements (objective and subjective) correspond with one another. The welfare position is characterized as well-being if objectively good living conditions are also subjectively evaluated as good or, in contrast, as deprivation if objectively unfavorable conditions are evaluated as unfavorable. Individuals with inconsistent welfare positions can be either subjectively satisfied with objectively unsatisfying living conditions (adaptation) or unsatisfied even though their living conditions are good (dissonance). Olson and Schober (1993) have labeled the former phenomenon as satisfaction paradox. Here, poor objective living conditions—in our case, characterized by low incomes—are evaluated subjectively as good or are characterized by positive life satisfaction despite poverty. The experience of the second inconsistent group has been described as the dissatisfaction dilemma. Persons belonging to this group have good objective living conditions yet simultaneously evaluate their income situation as subjectively bad.

Why are some people satisfied despite poor objective conditions or unsatisfied despite good objective conditions? From a combined theoretical and empirical point of view, discrepancies between objective living conditions and their subjective evaluation can be explained by various theories. In social psychological research and other health-related disciplines, such as medicine, the satisfaction paradox can be explained by differences in a person’s adaptation to demands, coping behaviors, individual personality traits, basic attitudes toward life, or set-points in life satisfaction (see Staudinger 2000; Herschbach 2002; Huck 2006; Filipp and Klauer 1991).

From a psychological point of view the manifestation of well-being depends strongly on individual fixed average levels of happiness. According to the set-point theory of well-being (Kuhn 1962; see also Fujita and Diener 2005; Headey 2007), set-points do not change except temporarily, when major life events occur. Brickmann and Campbell (1971) coined the adaptation theory of well-being as they observed that individuals returned to a baseline even after life-changing events. This phenomenon has been labeled the hedonic treadmill, with the baseline being referred to as the equilibrium level (Headey and Wearing 1989, 1992) or set-point (Diener, Lucas and Scollon 2006). According to Lucas et al. (2003), adaptations are quick, complete, and inevitable. Stability can be explained mainly because of personality and genetic predisposition (Lykken and Tellegen 1996). In this vein, Costa and McCrae (1980) show that individuals have different baselines of subjective well-being that are partly due to differences in their scores of stable personality traits.

Previous findings underline that personality matters for life satisfaction and well-being (see also Diener et al. 1999). For instance, the dimensions of extraversion and neuroticism have a positive and negative impact, respectively (see, for example, Watson and Clark 1984 or Lucas, Diener and Suh 1996). Self-esteem, self-efficacy, and a sense of coherence also play a relevant role (for an overview, see Herschbach 2002). According to Steel, Schmidt and Shultz (2008), life satisfaction in general is greater among people who are more open to new experiences, conscientious, extroverted, agreeable, and emotionally stable. In contrast, neuroticism leads to more depression and lower life satisfaction values.

Meanwhile, explanations offered by economic and sociological research focus on sociodemographic and economic differences, as well as how individuals compare their current situation to their past and to the situation of others. According to Zapf (1979b) and Glatzer, Berger and Zapf (1984), the traits of age, gender, educational level, and income are important determinants of well-being and welfare positions. Previous research describes a U-shaped relationship between life satisfaction and age (see, for example, Blanchflower and Oswald 2008 or Stone et al. 2010). However, the empirical results concerning gender-specific differences in life satisfaction are contradictory. While some studies have reported that women are more satisfied with their lives than men, others have found the opposite, and still others have observed negligible gender-differences (for an overview of related studies, see Joshanloo and Jovanović 2019). Another important determinant of life satisfaction is education. There are some hints that education has a significant effect on life satisfaction independent of its effect on income, with higher-educated individuals tending to be more satisfied with life in general (see Salinas-Jiménez, Artés and Salinas-Jiménez 2011). Furthermore, the relationship between individual economic resources, such as income, and subjective well-being is also positive but weak (see Schyns 2002, 2000; Diener and Oishi 2000).

In addition to demographic and economic differences, social comparative processes are important (Glatzer 1992). Psychologists like Festinger (1954) have argued that self-image depends strongly upon comparison to others, to personal norms and values, and between the actual situation and goals and targets (see also Argyle 1987; Veenhoven 1991). Similar to the Easterlin paradox (1974, see also 1995, 2001), which states that happiness does not increase as a country’s income rises, individuals rate their situation not according to objective, rational criteria but in comparison to significant others. From the perspective of social comparisons, life satisfaction should increase when the comparison with other individuals’ current situations or one’s own past situation leads to a positive result. Conversely, life satisfaction should decrease when the comparison with either others or the past leads to a negative result. In general, Dittmann and Goebel (2010) claim that some empirical evidence suggests that social networks have the strongest effect on individual life satisfaction. Analyzing neighborhood effects on life satisfaction, these authors noted higher life satisfaction among those living in a higher socioeconomic environment. Furthermore, well-being is also affected when a gap between individual economic status and the status of the neighborhood exists. Further research from Zou, Ingram and Higgins (2015) suggests that network density also makes a difference in satisfaction. Having a larger number of close relationships has a positive impact on an individual’s level of satisfaction with life (see also Diener and Seligman 2002; Reis and Gable 2007).

On the basis of theoretical implications and previous findings, this paper combines objective and subjective well-being to analyze individual welfare positions in Europe. As older people represent a growing population group in contemporary societies as well as one often marked by vulnerabilities, it seems beneficial to focus on this specific age group and shine light on the welfare positions of the older population in Europe. Against this background, it is important to bear in mind that the extent of (life) satisfaction and happiness vary widely across European countries (for an overview, see for example Huppert et al. 2009). Variations of well-being can be explained to a large extent by the economic performance, the social security level, and the political culture, which in turn enable people to live relatively comfortable (e.g., Böhnke 2008; Diener and Lucas 2000; Haller and Hadler 2006).

3 Data and Methods

Based on the aforementioned theoretical assumptions and previous research, this paper attempts to detect the occurrence of inconsistent welfare positions. As we focus on older Europeans, our analyses are based on the seventh wave of the SHARE, conducted in 2017 (for details on the data, please refer to Börsch-Supan 2020b). Specifically, we focused on information related to respondents aged 50 years and older in 26 European countries. As the SHARE includes different types of respondents for specific modules, we further restricted our sample to the so-called household respondents, as these individuals answered all questions related to objective income on behalf of the entire household.

To analyze possible causes of inconsistent welfare positions based on multilevel logistic regression models with the occurrence of the satisfaction paradox and the dissatisfaction dilemma set as dependent variables, we operationalized respondents’ individual welfare positions in accordance with the assumptions introduced by Zapf (1984).

First, the objective financial position was based on the overall income of the entire household (after taxes and contributions). Objective living conditions were further assigned to the categories “good” and “bad” based on the household’s relative income distribution. This was calculated using the household’s net equivalent income and the square root scale, which divides household income by the square root of all household members (for details, see OECD 2011, 2008). Households who live in precarity (characterized by less than 75% of the country-specific median household net equivalent income) were assigned to the category “bad”. All others above this threshold were considered to be living in an objectively “good” income position.

The subjective evaluation of respondents’ income position and a proxy of feeling financial restrictions were drawn from the question “how often do you think that shortage of money stops you from doing the things you want to do?” and the four answer categories: “often”, “sometimes”, “rarely”, and “never”. People who rarely or never experienced financial shortages were assigned to the category “good”, while those facing financial restrictions either often or sometimes in everyday life held a “bad” subjective income position.

To explain the two inconsistent welfare positions—that is, the so-called satisfaction paradox and the dissatisfaction dilemma—we took different indicators into account, controlling for individual and family-related characteristics. Moreover, to capture the influence of structural patterns and explain country-specific differences, we further included relevant contextual indicators. According to previous research, two important social-demographic indicators of discrepant individual welfare positions are age and gender. Given that migrants earn, on average, lower incomes (OECD 2015) and thus have a higher risk of objective poverty, we included the migration background of the respondents to measure differences attributable to ethnic and cultural discrepancies. Furthermore, the multivariate analyses also include the civil status of the respondent as well as the number of children. For number of children, respondents could choose between none, one, two, and three or more children. The question regarding civil status included the options of being either married, never married, divorced, or widowed.

To control for socioeconomic differences and class-specific patterns, we considered the individual level of education and the occupational status of the respondents. Level of education was recorded in accordance with the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) as (1) low (ISCED score of 0–2 points), (2) medium (ISCED score of 3–4 points), or (3) high (ISCED score of 5–8 points) education. Occupational status consisted of the following categories: (1) employed, (2) unemployed, (3) retired, and (4) not employed (such as being a homemaker or being permanently sick or disabled). Moreover, since previous research has shown that not only social comparisons matter but also comparing one’s current situation with the past, we further considered respondents’ past financial situation. Experienced financial hardship covers (1) those who had never exposed to a financially difficult situation and (2) those who have experienced or currently experiencing in financial hardship. However, this question was only included in the retrospective part of the seventh wave and was thus not asked of respondents who had already participated in the first retrospective version of SHARE, called SHARELIFE, in 2011 (for details, see Börsch-Supan 2020a). Therefore, information on financial hardship for these respondents was gathered from the SHARELIFE interview in 2011, meaning that the financial situation of respondents who did not report an experience of hardship in 2011 may have changed.

Furthermore, our estimations included indicators of subjective well-being and personality. One variable that may influence an individual’s evaluation of their economic situation is the physical health status. In reporting their physical health status, respondents could choose from five categories: (1) excellent, (2) very good, (3) good, (4) fair, and (5) poor. Additionally, we included overall life satisfaction on a linear scale, with scores ranging from zero to 10 points where zero points indicated a respondent was completely dissatisfied and 10 points indicated a respondent was completely satisfied.

Reported personality traits were based on the 10-item Big Five Inventory (BFI-10), which covers openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (for details, see John and Srivastava 1999). The traits that reflect having an openness to experiences include characteristics like being artistic, curious, original, and imaginative as well as “intellectual” attributes like being intelligent, insightful, and sophisticated. Conscientiousness covers individual differences in the propensity to be self-controlled and to delay gratification as well as to be task- and goal-directed, organized, efficient, precise, and deliberate. Extraversion encompasses characteristics such as sociability, activity, assertiveness, and positive emotions. In contrast with hostility or quarrelsomeness, agreeableness implies tender-mindedness (being sensitive, kind, soft-hearted, or sympathetic), altruism (being generous, helping, praising), and trust (being trusting or forgiving). Finally, neuroticism is characterized by feelings of tension, anxiety, and the tendency to be temperamental. This stands in contrast to a state of emotional stability, which is marked by calmness and contentedness. Each of these 5 personality dimensions was measured with 2 prototypical statements representing the high and the low poles of each factor, respectively. For each statement, respondents answered according to a five-point Likert scale that ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”.

Finally, potential regional and country-specific differences can be explained by cultural and contextual conditions. Therefore, we also controlled for respondents’ area of residence to capture regionally anchored differences within countries and to distinguish whether the respondents live in big cities, suburbs of big cities, large towns, small towns, or rural areas. To take country-specific differences into account, we further considered contextual indicators for each of the 26 European countries. In addition to the national economic power measured by the GDP per capita, we looked at the welfare distribution of states, as captured by the annual percentage of public social expenditures in relation to the GDP. Moreover, the general economic situation and recent economic crises in several European countries were captured by the national poverty rate (60% median line after taxes and transfers) and the extent of income inequality (Gini coefficient). All indicators at the country level were drawn from Eurostat and refer to the year preceding the interview.

To analyze the determinants of inconsistent welfare positions, we conducted separate multivariate analyses for both dependent variables: the satisfaction paradox and the dissatisfaction dilemma. Here, the satisfaction paradox included all respondents with an objectively bad income situation and distinguished between those who evaluate their financial situation as subjectively good (one point) or bad (zero points). In contrast, the analyses performed regarding the dissatisfaction dilemma covered all respondents with an objectively good income situation and differentiated between those who rate their situation as subjectively bad (one point) or good (zero points). Given the nonindependence between observations, the hierarchical data structure of the SHARE (45,726 respondents nested in 26 countries) violates basic regression assumptions and might result in inaccurate significance values as well as biased standard errors. Therefore, and based on the operationalization of our dependent variables, we analyzed inconsistent welfare positions by estimating multilevel logistic regressions (see, for example, Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal 2008). In addition to the fixed or released parameters at the individual level, these analyses included context variables separately to avoid estimation biases that stem from multiple macro-level indicators (Maas and Hox 2005). Moreover, all non-dichotomous variables have been standardized, resulting in all of these variables having a mean value of zero points and a standard deviation of one point (see Table 3 for sample characteristics in the annex).

4 Empirical Results

At first glance, the distribution of the objective situation and the subjective evaluation of older Europeans reveal that both measurements of welfare differ strongly among countries. The objective income situation, as measured by the annual median net household equivalent income and adjusted for purchasing power parity, varies strongly across Europe (see Fig. 1). While elderly Europeans have, on average, almost 14,400 euros per year, the average is by far the highest in Luxembourg (around 32,000 euros), followed by Switzerland (approximately 25,000 euros) and Denmark (23,000 euros). In contrast, elderly residents in Romania average the lowest median household income in Europe, receiving less than 4600 euros per year, followed by those in Bulgaria (5470 euros) and Latvia (5650 euros). Overall, the distribution of the objective income highlights a European divide in which the countries in Northern and Western Europe achieve incomes (from labor, pensions, or other sources) above the European average, while those in Southern and Eastern earn incomes below the average.

Furthermore, the distribution of the subjective evaluation of the income situation also differs across Europe (see Fig. 2). In general, around 48% of all people in Europe aged 50 + years stated that they often or sometimes experience financial constraints. Again, however, the proportions differ sharply between countries. While the percentage of self-reported difficulties in Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, and Austria was under 30%, the rates were significantly higher in major parts of Southern and Eastern Europe. In Greece, for instance, roughly 90% of the older population reported that a shortage of money stops them from doing the things they want to do. This rate is also high in Lithuania (76%), Latvia (75%), Bulgaria (68%), Romania (67%), and Cyprus (67%). Meanwhile, in Luxembourg, Germany, and Belgium, followed by Finland, Hungary, Slovakia, and France, there is a comparatively low proportion of families who face financial constraints in everyday life. Thus, all Southern and Eastern European countries (with the exception of Hungary and Slovakia) experience financial restrictions above the European average. Moreover, such country-specific patterns remain generally constant if one were to focus only on those respondents who indicated that their financial situation often blocks them from doing things they want to do. While less than 17% of all Northern and Western Europeans, as well as respondents from Malta and Slovakia, often face such shortages, respondents in Greece (57%) experience such critical situations more often, followed by a considerable proportion of persons aged 50 + years living in Lithuania (48%), Latvia (42%), and Romania (41%). In relation to the European average, almost all other Southern and especially Eastern European countries show higher rates of individuals facing regular economic restrictions, meaning that older respondents in these countries must deal with financial shortages more often than those in the Northern and Western parts of Europe.

If we further compare the overall situation of objective and subjective financial hardship in Europe, we have to note a considerable mismatch between these two income measurements (see Fig. 3). While approximately 48% of elderly Europeans are confronted at least sometimes with feelings of financial shortages, less than 29% can be considered poor according to their objective financial situation (i.e., earning less than 75% of the national net median income, adjusted for household size). However, this unbalanced situation again varies strongly amongst the European countries. While the proportion of elderly Europeans with an objectively “bad” income situation differs across Europe (ranging from 20% in the Czech Republic to 36% in Cyprus), the differences are more pronounced when considering the subjective ability to participate in activities that require money. Here, the results show that the discrepancy between the objective and subjective situation is more pronounced in Eastern and Southern European countries. For instance, more older Europeans in Greece report financial constraints than report being in an objectively poor income situation. While 90% of the Greek population 50 + years old often or sometimes experience money shortages, only one in four have less than 75% of the national median income available and live, therefore, in an objectively precarious financial situation. The discrepancy between subjective feelings versus objective situations is especially remarkable in Latvia (77% vs. 29%), Lithuania (76% vs. 27%), and Estonia (62% vs. 24%). Meanwhile, in Western and Northern European countries, individuals’ objective situation and their subjective feelings are better aligned (especially in Luxembourg, Germany, and Austria). In some cases, objective situations of financial precarity even outweigh the subjective feelings of financial problems. This can be seen especially in Denmark, Sweden, and Switzerland.

Although individuals’ self-evaluation of their financial situation does sometimes differ from an objective measurement, the subjective and objective distribution of individual welfare positions for older persons living in Europe are often congruent with each other (see Fig. 4). Overall, more than 42% of elderly Europeans live in an objectively favorable income situation and are simultaneously aware of this, putting them in the category of well-being. In contrast, approximately 18% of the older population in Europe is characterized by deprivation, in which a bad objective position goes hand-in-hand with a bad subjective evaluation.

Still, more than one-third of the elderly respondents exhibited inconsistent objective and subjective welfare positions. Specifically, 29% showed dissonant positions (dissatisfaction dilemma), while 10% have adapted subjectively to their bad income situation (satisfaction paradox). In line with the variations between objective and subjective income across Europe (as shown in Fig. 3), the extent of the satisfaction paradox and dissatisfaction dilemma varies widely across Europe. There is considerable variation both in the extent of objective poverty and the perception of one’s income situation between countries as well as in the specific combinations of objective income situations and subjective perceptions within the observed countries. Older people living in a situation of well-being—meaning good objective and subjective conditions at the same time—most often reside in Denmark (59%), Sweden (58%), Austria (57%), Luxembourg (56%), Germany (55%), Denmark (54%), and Switzerland (54%). In contrast, this state of well-being is enjoyed by a comparably low percentage (under 30%) of the elderly population in Lithuania, Latvia, Cyprus, Romania, Bulgaria, and Croatia—especially in Greece, where the rate is only 9%. When focusing on the welfare position of deprivation, which means that people evaluate their poor objective income situation as bad, we can observe that the highest proportions (between 20 to 27%) are localized to Southern and Eastern European countries. In contrast, this situation appears to be relatively rare in Denmark (8%) and Sweden (10%). With rates between 12 and 17%, all other Northern and Western European welfare regimes show a level of deprivation that is below the European average (18%). This underscores the conclusion that deprivation is generally less pronounced in these areas than in the Southern and Eastern parts of Europe (with the exceptions of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Malta).

Like the consistent welfare positions, the discrepant forms also vary between European countries. Older people in the Southern and Eastern parts of Europe are more often dissatisfied with their financial situation even though their economic earnings are objectively good (dissatisfaction dilemma). However, in many Northern and Central European countries, the generation aged 50 + years displays the satisfaction paradox more frequently. The dissatisfaction dilemma occurs very often in Greece, with 65%, and appears to be comparatively rare (18% or lower) in Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, Germany, Luxembourg, and Austria. By contrast, the satisfaction paradox is most common in Northern and Western Europe. For instance, more than one-fifth of all older residents in Denmark report experiencing no financial shortages, even though they are objectively in an uncomfortable financial situation. This applies as well to members of the older population living in Switzerland, Sweden, Luxembourg, Finland, Austria, Belgium, Germany, and France, who report above-average rates of subjective satisfaction despite living in objective precarity.

To explain deviations between the objective economic situation of respondents and their subjective evaluation, we estimated multilevel logistic regression model (see Table 2). Overall, with increasing age, people tended to be more likely to be satisfied with their subjective income position even if their objective income situation was poor. In contrast, the likelihood of the dissatisfaction dilemma decreased with increasing age. Moreover, men tended to be more often satisfied with an objectively bad income situation than women. In contrast, women were more often dissatisfied with their income situation even when they lived in objectively good economic conditions. Migrants showed the satisfaction paradox less often and are thus less frequently satisfied with their bad objective situation than natives. Additionally, migrants are more often dissatisfied with their financial situation even when their objective income is not categorized as bad.

Furthermore, family situation seems to matter. As compared with married Europeans, in particular, divorced persons—who may rely on or have to pay alimony—less often find themselves in evaluating their poor financial resources as good. It seems that a partnership, and thus the possibility of various income streams, can somewhat compensate for objective financial restrictions. Single and divorced Europeans are, therefore, more often dissatisfied even when the objective situation is good. Furthermore, having children, which typically leads to a need for increased financial resources, reduces the satisfaction paradox and promotes also the probability of the dissatisfaction dilemma.

Further, socioeconomic circumstances influence the occurrence of both the satisfaction paradox and the dissatisfaction dilemma. An individual’s level of education is strongly linked to both dissonant positions. Here, tertiary-educated individuals tend to be more often satisfied with their objectively bad income situation. Similarly, having higher educational credentials prevents the bearers from feeling dissatisfied when living in an objectively good economic situation. A person’s occupational situation also plays a role. Gainfully employed older Europeans as well those who are economically inactive (such as pensioners, homemakers, or permanently sick individuals) and who may receive income from other sources or household members are more often satisfied in an objectively uncomfortable income position than those who are unemployed. In turn, the dissatisfaction dilemma occurs more often for respondents who temporarily had to leave the labor force due to unemployment or due to being a homemaker, permanently sick, or on parental leave. However, the explanation behind a match or mismatch of welfare positions goes beyond a person’s current professional and economic conditions. How an individual’s current situation compares with their past economic situation matters, too. Older people who have experienced financial hardship in their lives show the satisfaction paradox significantly less often and the dissatisfaction dilemma more often. This pattern indicates that past financial situations have a lasting effect when evaluating current financial conditions.

Besides sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics, subjective indicators such as health status, general life satisfaction, and personality traits could help explain a mismatch in welfare positions. While older Europeans who report poor health show the dissatisfaction dilemma more often, the reverse is true for the satisfaction paradox, which occurred more often among respondents who reported being in excellent or very good health. In contrast, respondents who show a higher level of general life satisfaction are less likely to report financial problems despite their financial situation being objectively poor. They are also less likely to feel financially challenged when their situation is objectively good. In addition, personality, which previous research has identified as an important factor in general life satisfaction and happiness, has a limited effect on a person’s welfare position. Extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness have no significant impact. However, neuroticism and openness are essential characteristics for explaining a mismatch in welfare positions. Older Europeans with higher levels of neuroticism and openness tend to be more often subjectively dissatisfied with their objectively good income situations. Higher levels of neuroticism and openness seem to promote a more realistic level of self-assessment, since the higher the values for these personality traits, the less often the satisfaction paradox occurs.

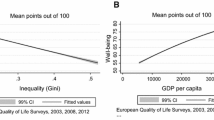

Finally, our empirical results reveal not only differences due to sociodemographic and socioeconomic indicators and social-psychological and subjective aspects but also differences that can be attributed to contextual influences. Regional differences based on population density within countries are only important for explaining the dissatisfaction dilemma, with dissatisfied income feelings occurring significantly more often in densely populated areas than in small towns or rural areas. Moreover, structural differences between European countries have a noticeable impact on situations of adaptation and dissonance. Here, the higher the prosperity of a country in general (as measured by the GDP per capita), the more often the satisfaction paradox occurs and the less often individuals are dissatisfied with objectively good income situations. In stronger welfare states with higher social expenditures, older people experience feelings of financial shortage less often, even though their objective income position is bad, than those in countries with lower social protection levels and higher occurrence rates of the dissatisfaction dilemma. In line with the country-specific level of economic power and welfare state arrangements, the economic uncertainties of European societies matter as well. Older persons living in countries with higher poverty rates and more income inequality present the satisfaction paradox less often. In contrast, the dissatisfaction dilemma occurs more often in European countries with higher risks of poverty and unequal distribution of income.

5 Conclusions

The objective distribution of income and as well as the subjective evaluation of one’s financial situation are important manifestations of one’s opportunities in life. On an individual level, objective and subjective welfare positions can correspond with one another or deviate from each other. Analyzing the causes of the two forms of nonconformance—namely, adaptation (satisfaction paradox) and dissonance (dissatisfaction dilemma)—this paper concludes that, overall, the older population in Europe falls into the category of well-being. Nearly every second older European lives in a relatively comfortable income situation and has no problem making ends meet. In contrast, 18% report living in an objectively bad income situation and feeling those financial restrictions. A further 10% are satisfied, although their financial situation is objectively bad, while 21% of the older population feel financial constraints even though their objective income is good. However, this pattern is not consistent across Europe. While older persons in Denmark, for instance, often show the satisfaction paradox, this phenomenon is almost nonexistent in Greece. Moreover, the highest proportion of dissatisfied older persons in a relatively good objective economic situation can be found in Greece, while Danish and Swedish residents experience the lowest rates of dissonance. Overall, we can observe a division between the Northern and Western European countries on one side and the Southern and Eastern parts of Europe on the other. The empirical results suggest that the satisfaction paradox is a phenomenon that we can observe mainly in the North and West of Europe, while in the South and East, the occurrence of the dissatisfaction dilemma is more prevalent.

How can we explain occurrences of the satisfaction paradox or the dissatisfaction dilemma? Beyond sociodemographic and socioeconomic determinants, subjective indicators (physical and psychological) influence a mismatch between objective and subjective income measurements. Compared to younger generations, older Europeans tend to be more often satisfied with their subjective income positions even if their objective income situation is bad. This indicates that the satisfaction paradox becomes more prevalent with increasing age, while the dissatisfaction dilemma is more common among the young. Moreover, our results highlight gender-specific differences in that, compared to women aged 50 + years, men tend to be more often satisfied despite objectively poor financial resources and simultaneously less often dissatisfied with good living conditions. Differences caused by migration, civil status, and family size should also factor in to welfare positions.

Next to sociodemographic indicators, economic resources and educational qualifications play an important role. Here, education seems to be relevant for explaining mismatches between objective and subjective income situations. The higher their level of education, the less often an individual is dissatisfied with good objective conditions, and vice versa. Furthermore, the occupational status and the accumulated assets of an entire household may help determine whether an individual experiences a situation of adaptation or dissonance. An individual’s subjective assessment is also influenced by how their current financial situation compares to their past situation. Individuals who have experienced financial hardship are less often satisfied with bad income positions. Instead, they are dissatisfied significantly more often than their peers, even when they do not live objectively precariously.

Finally, well-being in general has a lasting effect on individuals’ welfare positions. Older Europeans who are healthier (both physically and mentally) and more pleased with their life but who show less openness are more often satisfied when their objective income position is bad, and vice versa. The presence of the dissatisfaction paradox is linked to worse health, higher levels of neuroticism, and a general dissatisfaction with one’s life situation.

Country-specific differences can mainly be explained against the background of welfare state arrangements and countries’ differing economic situations. Older people from stronger welfare states are more often satisfied even when their objective situation is bad. In contrast, they are less often dissatisfied in objectively good income situations. For societal poverty and income inequality, we can observe the opposite relationship. Persons from countries with greater societal poverty rates and income inequality show the satisfaction paradox less often, while they are more often found in the dissatisfaction dilemma.

However, what are the consequences? Although the majority of older Europeans live objectively and subjectively in a relatively comfortable welfare position, the question and reality about an apparent discrepancy between objectivity on one side and subjectivity on the other side can cause some problems. For individuals, it seems to be psychologically important that welfare positions are consistent with each other; otherwise, the mismatch can cause cognitive dissonance. Indeed, subjective assessments can become objectively real by virtue of the Thomas theorem, which states that “if men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (Thomas and Thomas 1928). Thus, a subjectively “bad” evaluated income situation can influence a persons’ behavior in general and their social participation in particular, even if there is no objective reason for their decisions. For social policy, it also seems especially important to consider those individuals who are satisfied despite an objectively bad situation, because they are often invisible with respect to state interventions. Therefore, sociological research should take the discrepancies between objective and subjective income positions into account more fully and combine both concepts systematically.

References

Argyle, M. (1987). The psychology of happiness. London: Methuen.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.030

Böhnke, P. (2008). Does society matter? Life satisfaction in the enlarged Europe. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9169-4

Börsch-Supan, A. (2020a). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 3 - SHARELIFE. Release version: 7.1.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set.

Börsch-Supan, A. (2020b). Survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE) wave 7. Release version: 7.1.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set.

Börsch-Supan, A., Brandt, M., Hunkler, C., Kneip, T., Korbmacher, J., Malter, F., et al. (2013). Data resource profile: The survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE). International Journal of Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt088

Brickmann, P., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In M. H. Appley (Ed.), Adaptation-level theory (pp. 287–305). New York: Academic Press.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(4), 668–678.

del Mar Salinas-Jiménez, M., Artés, J., & Salinas-Jiménez, J. (2011). Education as a positional good: A life satisfaction approach. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9709-1

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. E. (2000). Explaining differences in societal levels of happiness: Relative standards, need fulfillment, culture, and evaluation theory. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010076127199

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollon, C. N. (2006). Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. The American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.305

Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 185–218). Cambridge, MA, US: The MIT Press.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00415

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

Dittmann, J., & Goebel, J. (2010). Your house, your car, your education: The socioeconomic situation of the neighborhood and its impact on life satisfaction in Germany. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9489-7

Donisi, V., Tedeschi, F., Gonzalez-Caballero, J. L., Cresswell-Smith, J., Lara, E., Miret, M., et al. (2020). Is mental well-being in the oldest old different from that in younger age groups? Exploring the mental well-being of the oldest-old population in Europe. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00292-y

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 89–125). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(95)00003-B

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. The Economic Journal. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00646

Eurostat (2019a). Expenditure: main results [spr_exp_sum]. https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=spr_exp_sum&lang=en. Accessed 14 November 2019.

Eurostat (2019b). GDP per Capita in PPS: tec00114. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tec00114&plugin=1. Accessed 10 November 2019.

Eurostat (2019c). Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey: [ilc_di12]. https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_di12&lang=en. Accessed 14 November 2019.

Eurostat (2019d). People at Risk of Poverty or Social Exclusion by Age and Sex: [ilc_peps01]. https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_peps01&lang=en. Accessed 14 November 2018.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Filipp, S.-H., & Klauer, T. (1991). Subjective well-being in the face of critical life events: The case of the successful copers. In F. Strack (Ed.), Subjective well-being: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 213–234). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Flik, R. J., & van Praag, B. M. S. (1991). Subjective poverty line definitions. De Economist. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01423569

Fujita, F., & Diener, E. (2005). Life satisfaction set point: Stability and change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.158

Glatzer, W. (1992). Lebensqualität und subjektives Wohlbefinden. Ergebnisse sozialwissenschaftlicher Untersuchungen. In A. Bellebaum (Ed.), Glück und Zufriedenheit: Ein Symposion (pp. 49–85). Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Glatzer, W., Berger, R., & Zapf, W. (Eds.). (1984). Lebensqualität in der Bundesrepublik: Objektive Lebensbedingungen und subjektives Wohlbefinden. Frankfurt am Main: Campus-Verlag.

Hagenaars, A., & de Vos, K. (1988). The definition and measurement of poverty. The Journal of Human Resources. https://doi.org/10.2307/145776

Hagerty, M. R., Cummins, R., Ferriss, A. L., Land, K., Michalos, A. C., Peterson, M., et al. (2001). Quality of life indexes for national policy: Review and agenda for research. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique. https://doi.org/10.1177/075910630107100104

Haller, M., & Hadler, M. (2006). How social relations and structures can produce happiness and unhappiness: An international comparative analysis. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-6297-y

Hansen, T., & Slagsvold, B. (2012). The age and subjective well-being paradox revisited: A multidimensional perspective. Norsk Epidemiologi. https://doi.org/10.5324/nje.v22i2.1565

Headey, B. (2007). The set-point theory of well-being: Negative results and consequent revisions. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9134-2

Headey, B., & Wearing, A. J. (1989). Personality, life events, and subjective well-being: Toward a dynamic equilibrium model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.4.731

Headey, B., & Wearing, A. J. (1992). Understanding happiness: A theory of subjective well-being. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

Herschbach, P. (2002). Das „Zufriedenheitsparadox” in der Lebensqualitätsforschung. PPmP - Psychotherapie · Psychosomatik · Medizinische Psychologie, doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-24953.

Huck, G. (2006). Gesundheitsförderung in der Psychiatrie: Konzepte und Modelle. In W. Marschall, J. Utschakowski, & M. Gassmann (Eds.), Psychiatrische Gesundheits- und Krankenpflege & Mental Health Care (pp. 39–64). Berlin: Springer.

Huppert, F. A., Marks, N., Clark, A., Siegrist, J., Stutzer, A., Vittersø, J., et al. (2009). Measuring well-being across Europe: Description of the ESS well-being module and preliminary findings. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9346-0

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The big-five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Joshanloo, M., & Jovanović, V. (2019). The relationship between gender and life satisfaction: Analysis across demographic groups and global regions. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-019-00998-w

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lara, E., Martín-María, N., Forsman, A. K., Cresswell-Smith, J., Donisi, V., Ådnanes, M., et al. (2020). Understanding the multi-dimensional mental well-being in late life: Evidence from the perspective of the oldest old population. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00090-1

Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2003). Reexamining adaptation and the set point model of happiness: Reactions to changes in marital status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 527–539.

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., & Suh, E. M. (1996). Discriminant validity of well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.616

Lykken, D., & Tellegen, A. (1996). Happiness Is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00355.x

Maas, C. J. M., & Hox, J. J. (2005). Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241.1.3.86

OECD. (2008). Growing unequal? Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2011). Divided we stand: Why inequality keeps rising. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2015). Indicators of immigrant integration 2015. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Olson, G. I., & Schober, B. I. (1993). The satisfied poor: Development of an intervention-oriented theoretical framework to explain satisfaction with a life in poverty. Social Indicators Research, 28(2), 173–193.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2008). Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using stata. College Station, Texas: Stata Press.

Reis, H. T., & Gable, S. L. (2007). Toward a positive psychology of relationships. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (4th ed., pp. 129–159). Washington, DC: American Psychological Assoc.

Ringen, S. (1988). Direct and indirect measures of poverty. Journal of Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279400016858

Schyns, P. (2000). The relationship between income, change in income and life-satisfaction in West Germany and the Russian Federation: Absolute, relative or a combination of both? In E. Diener & D. R. Rahtz (Eds.), Advances in quality of life theory and research (pp. 83–109). Dordrecht, London: Kluwer Academic.

Schyns, P. (2002). Wealth of nations, individual income and life satisfaction in 42 countries: A multilevel approach. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021244511064

Smith, J., Borchelt, M., Maier, H., & Jopp, D. (2002). Health and well-being in the young old and oldest old. Journal of Social Issues. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00286

Staudinger, U. M. (2000). Viele Gründe sprechen dagegen, und trotzdem geht es vielen Menschen gut: Das Paradox des subjektiven Wohlbefindens. Psychologische Rundschau. https://doi.org/10.1026//0033-3042.51.4.185

Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.138

Steptoe, A., Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2014). Psychological wellbeing, health and ageing. Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0

Stone, A. A., Schwartz, J. E., Broderick, J. E., & Deaton, A. (2010). A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1003744107

Thomas, W. I., & Thomas, D. S. T. (1928). The child in America: Behavior problems and programs. New York: A. A. Knopf.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00292648

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.96.3.465

Zapf, W. (1979). Applied social reporting: A social indicators system for West German society. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00289435

Zapf, W. (1979b). Lebensbedingungen und wahrgenommene Lebensqualität. In J. Matthes (Ed.), Sozialer Wandel in Westeuropa: Verhandlungen des 19. Deutschen Soziologentages, 17. - 20. April 1979 im Internationalen Congress Centrum (ICC) in Berlin (pp. 767–790, Verhandlungen des … Deutschen Soziologentages, Vol. 19). Frankfurt/Main: Campus-Verlag.

Zapf, W. (1984). Individuelle Wohlfahrt: Lebensbedingungen und wahrgenommene Lebensqualität. In W. Glatzer, R. Berger, & W. Zapf (Eds.), Lebensqualität in der Bundesrepublik: Objektive Lebensbedingungen und subjektives Wohlbefinden (pp. 13–26). Frankfurt am Main: Campus-Verlag.

Zou, X., Ingram, P., & Higgins, E. T. (2015). Social networks and life satisfaction: The interplay of network density and regulatory focus. Motivation and Emotion. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9490-1

Acknowledgements

This paper uses data from SHARE Wave 3 and 7 (DOIs: https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w3.710, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w7.710); see Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details. The SHARE data collection has been funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812), FP7 (SHARE-PREP: GA N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: GA N°227822, SHARE M4: GA N°261982), and Horizon 2020 (SHARE-DEV3: GA N°676536, SERISS: GA N°654221) and by DG Employment, Social Affairs, and Inclusion. Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the United States National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, HHSN271201300071C), and various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see http://www.share-project.org/).

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The following research has been conducted according to ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Isengard, B., König, R. Being Poor and Feeling Rich or Vice Versa? The Determinants of Unequal Income Positions in Old Age Across Europe. Soc Indic Res 154, 767–787 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02546-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02546-x