Abstract

This study employs the synthetic control method to assess the effects of Romania’s 2016 research reforms on the nation’s research output. Prior reforms were unstable and led to persistent deviations from international publication practices, where a disproportionate share of national research was published in national journals and subsequently in conference proceedings. The 2016 reforms, which introduced rigorous publication quotas and criteria, including reduced emphasis on conference proceedings, were notably stable. However, these reforms coincided with a consistent reduction in research funding. To understand the impact of the tension between increased publication demands and reduced research funding, the study analysed changes in research output distribution before and after the reform, focusing on total scientific output, conference proceedings, and articles published in MDPI and non-MDPI journals. The results revealed a significant decline in overall scientific production following the intervention. This decrease can be attributed to two key factors. First, the shift away from conference proceedings was not fully compensated for by the increase in articles published in MDPI journals. Second, there was also a decline in the articles published in non-MDPI journals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research drives economic growth, fosters technological innovation, propels social progress, and boosts international competitiveness. It also serves as a source of national prestige and pride. These factors motivate nations to establish robust research systems, with adequate resource allocation being a key determinant of success. The surge in government research expenditures over the past decades, with a more than threefold increase in global research and development spending between 2000 and 2019 (National Science Foundation, 2022), underscores the growing emphasis on research investments. Empirical evidence aligns with this trend, indicating that larger research spending generally leads to higher research output (Courtioux et al., 2022; Docampo & Cram, 2017; Ebadi & Schiffauerova, 2016; Lin et al., 2014).

Beyond funding, governments also seek to optimize research fund distribution. Performance-based research funding is gaining popularity among various existing funding mechanisms due to its potential to increase and improve scientific production through competition and accountability. Recent data on the countries that have adopted performance-based research funding show a significant positive impact on research output (Banal-Estañol et al., 2023; Cattaneo et al., 2016; Checchi et., 2019). However, inconsistencies between research funding goals and incentive structures (Civera et al., 2020; Elton, 2000), diminishing returns (Geuna & Martin, 2003), and increasing complexity and costs over time (Martin, 2011) can undermine the intended effects.

While many countries have ensured adequate resources and successfully implemented and calibrated performance-based research funding systems, others have struggled, and their governments have been sending mixed signals regarding their intentions and expectations (Lepori et al., 2009). This study focuses on such a case, specifically on Romania, a country with a history of highly fluctuating research policies and permeable academic integrity norms. In 2016 Romania implemented its most stable research reform. The research policies adopted then made the minimum criteria for academic hiring and promotion more stringent, by marginalizing conference proceedings and requiring publications in journals with an impact factor. However, despite enforcing more demanding criteria, the government started reducing its allocations for research spending. How has the gap between rising publication demands and diminished research funding impacted Romania’s research output? To address this question, the article initially describes the research context, formulates the most likely scenarios, and then tests them by analyzing shifts in the distribution of research output using the synthetic control method.

Romania: a history of incomplete and unstable research reforms

The communist period: setting up a difficult transition

While science endured significant setbacks under communist rule across the former Eastern Bloc, Romania’s plight was particularly dire. At the outset of the communist era, Romania’s anti-Bolshevik stance and limited urban proletariat presented a formidable challenge to the Soviet takeover, leading to the most severe large-scale persecutions within the Communist Bloc. These persecutions decimated Romanian elites, opening the way to extreme political control over scientists (Judt, 2005; Tismăneanu, 2003).

Despite an initial period of seeming liberalization, the control and marginalization of science were further exacerbated under Nicolae Ceaușescu. First, the dictatorship’s grip on the country grew so strong that in the last decade of the communist rule, Romania had only two independent movements, considerably fewer than other communist countries, and was the only country in the Bloc that did not have an underground publication (Linz & Stepan, 1996). Second, Ceaușescu’s outdated vision of a Stalinist economy favored research projects centered on heavy machinery, manufacturing, construction, and related industries, while almost completely neglecting basic research (Eisemon et al., 1996). Third, the imposition of a rigid and autarchic national-communist ideology forced social and humanistic sciences to endorse ludicrous theories and subjected them to severe reprisals when the regime perceived any deviation from the approved lines of inquiry (Boia, 2001). The autarchic policies also severely restricted communication between Romanian researchers and the international scientific community in most fields of study. As a result, Romania was left with a significantly weaker scientific output and international collaboration compared to other communist states (Teodorescu & Andrei, 2011).

The post-communist period: quick and strong reconstitution, slow and fragile reform

Romania was the last to transition from communism in the region and its transition was slow and difficult. Because Ceaușescu eliminated the political actors necessary for a “pacted transition”, his removal from power was followed by a reconstitution of the regime by the communist elites (Linz & Stephan, 1996). In many ways, in the first years after the fall of the dictator, Romania experienced continuation rather than reform. For instance, while other former communist countries were reforming their research institutes and universities (Tarlea, 2017; Waligóra & Górski, 2022), it took Romania five years to enact its first education law. Even though this law introduced some departures from the past, change was often met with fierce resistance (Boia, 2001).

The economic legacy of Ceaușescu’s regime, however, did force some significant changes. The collapse of the outdated communist economic system plunged the country into a severe economic downturn, taking over a decade to recover to its 1989 GDP level. This had a profound impact on the research institutions linked to the struggling industries, as research funding was barely sufficient to cover salaries (Eisemon et al., 1996). Consequently, Romania’s R&D personnel decreased dramatically, falling from a total of 150,000 employees in 1989 to 38,433 in 2002 (Florian, 2004).

The changing economic landscape also had a profound impact on higher education. While Romania had approximately 12,000 university teaching staff and 165,000 undergraduate students in 1989, most pursuing technical specializations, the higher education sector underwent a dramatic transformation in the following years. Fueled by the appearance of new state universities and the first private universities on one hand, and by an input-based funding mechanism and the introduction of tuition-paying students on the other hand, the number of teaching staff nearly tripled, reaching 32,000, while the number of undergraduate students rose to 900,000, with a substantial shift towards social science disciplines and private universities. This explosive growth, however, was followed by a period of decline that disproportionately affected the newly established private universities. Over the past decade, student enrollment has stabilized at around 410,000 annually and teaching staff at around 26,000 (National Institute of Statistics, 2023).

The sudden and substantial growth in the number of academic staff mainly occurred in the expanding fields of social sciences, where there was a shortage of qualified specialists. This required significant professional and ideological reconversion, and the university hiring and promotion standards were low. A study of that period showed that Romanian academics mostly published their scientific articles in low-quality national journals. The ratio of articles published in national journals to Web of Science (WoS) articles was 8 to 1 in 2003, while the ratio of books published by national publishers to international publishers was 15 to 1 (Florian & Florian, 2006). In time, Romanian researchers learned to index their national journals in WoS, a trend they shared with colleagues from other former communist countries. However, as several analyses have shown, these journals were largely used for “local promotions and formal fulfilment of policy rules” and Romania was among the countries engaging most frequently in such behaviors (Hladcenko & Moed, 2021; Pajic, 2015).

Another idiosyncratic and repetitive feature of Romanian research reform has been its tendency to be undermined by resistance justified by autarchic sentiments. In 2005, under the leadership of a reformist minister, the government introduced stricter academic hiring and promotion criteria based on WoS publications. Previous guidelines had merely stipulated quantitative requirements without specifying how many articles needed to be published in “internationally recognized journals”, and without defining what international recognition means. For the first time in Romania’s post-communist history, the new criteria, however, specified a minimum number of articles published in WoS-indexed journals: four in the past 5 years for a professor and two for an associated professor. Yet, this reform was disingenuously undone just a few months later by an amendment that, while seemingly raising the minimum number of required articles, also allowed candidates to substitute some or all WoS articles with a specific number of publications in other journals.

A similar situation recurred a few years later. In 2011, a reformist minister introduced stricter hiring and promotion criteria for higher education and research, but these standards, together with other important reformist policies, were significantly weakened in 2012 and 2013. The 2011 criteria explicitly emphasized WoS indexing and incorporated journal impact factor or article influence score into their formulas. Again, the subsequent countermeasures permitted alternatives: while the stricter criteria imposed a minimum score exclusively based on articles published in WoS journals with an impact factor, subsequent modifications allowed proceeding papers to contribute to this minimum score.

Post-communist Romania has also struggled with plagiarism amid a deep-seated culture of corruption, where politicians and other elites have fraudulently obtained doctoral degrees to elevate their social status. Despite Romania’s lower educational investment and research productivity compared to most of Europe, it surprisingly has a higher ratio of doctoral to tertiary students, at 4.11% versus the EU average of 3.63% (Eurostat, 2023). The discrepancy is largely due to funding structures and salary incentives that favor doctoral candidates, highlighting a problematic nexus between political elites and universities that compromises academic integrity. This relationship has led to power abuses, including altering regulations and dissolving institutions to shield individuals accused of plagiarism, with recent cases showing persistent unethical behavior and even severe retaliation against anti-plagiarism advocates (Abbott, 2012; Ghiațău, 2021; Ives et al., 2017; Stan & Turcescu, 2004).

The 2016 reform: a new beginning or a déjà vu in disguise?

Hiring and promotion criteria

In 2016, Romania implemented its most stringent reformist criteria for hiring and promotion to academic positions. These new standards mandated publication in international journals with an impact factor (IF) for candidates in most disciplines. As an example, in psychology, prior reformist guidelines allowed for full professorship qualification with a single article published in a journal with an article influence score of at least 0.25. In contrast, the newly introduced criteria established a formula requiring a minimum of five articles published in journals with an IF of 1 or fewer articles in higher IF journals. Additionally, while previous standards did not require primary authorship, the 2016 criteria introduced this constraint while excluding articles published in journals with an IF below 1.

Funding mechanism

The 2016 reforms also targeted Romania’s university funding, where efforts to introduce a performance-based funding system have also followed a winding path. After 1989, funding was primarily allocated based on inertial factors. From 1999 to 2003, an input-based funding formula was implemented, distributing funds proportionately to student enrollment. Between 2003 and 2011, this input-based system was complemented by “quality indicators” that evaluated teaching staff, research output, material resources, and university management. However, the impact of these quality indicators remained limited, accounting for only 6.5% of total funding during this timespan (Vîiu, 2015).

In 2012, the Romanian government introduced a funding system that distinguished between a basic, size-based component, and a supplemental, quality-based component. Initially, the supplementary component was based on a five-level ranking of academic programs by study cycle (undergraduate, master, and doctoral). The philosophy behind this system was to help transform the most promising Romanian universities into research-oriented universities, whereas the rest were to become teaching-oriented universities (Vlăsceanu & Hâncean, 2015). Consequently, only the top-ranking departments were to receive money.

Because resistance against this dichotomizing approach was strong, from 2016 onward, supplementary funding has been based on 15 indicators applied by scientific discipline. These quality indicators, which ensured a more uniform distribution of funding, address four key areas: (1) teaching, (2) research, (3) internationalization, and (4) regional focus and social equity. In short, the current funding scheme comprises two main components: basic funding based on student enrollment, accounting for 72% of the total funding; and supplementary funding based on quality indicators, representing 26.5%.

While supplementary funding is domestically categorized as performance-based (Păunescu et., 2022), international comparisons exclude Romania due to its lack of a fully implemented performance-based research funding system (Checchi et., 2019; Zacharewicz et al., 2019). To clarify this issue, it should be stated that although some quality indicators consider research outputs, supplementary funding itself is not specifically designated for research purposes. According to current national regulations, university administrators can utilize these funds to enhance their best-performing departments as deemed appropriate. Research spending is a potential use of these funds, but in practice, the absence of robust accountability mechanisms hinders a comprehensive assessment of how this money is spent. However, universities use some money to invest in research. A noteworthy post-2016 development is that an increasing number of universities invest in internal grants that enable all academic staff to cover publication fees for open-access journals. For instance, Romania’s largest university is offering annually around $1,000 per employee via internal seed grants that can be used to cover “expenses for the publication of articles in renowned journals,” because the university supports “free access to research results, especially open science” (Babeș Bolyai University, 2023).

Another issue with supplementary funding is that many of the so-called quality indicators measure quantity (e.g., number of published articles or books) and are weighted by university size. Since institutional size is the prime predictor of research production (Docampo & Cram, 2017), it should be unsurprising that when we analyze the data provided by the National Council for the Financing of Higher Education (NCFHE) on the funding of the 46 Romanian state universities, there is a very strong correlation (r = 0.931) between the basic and supplemental funding components (NCFHE, 2023).

However, the most important for the current discussion is that the research output indicators implemented in 2016 are based on the strict hiring and promotion criteria established in the same year. This alignment creates a situation where the pressure to publish numerous articles in WoS-indexed journals is not just an individual concern but also a broader institutional imperative. While individual researchers may delay promotion applications, universities are subjected to annual evaluations, making them highly motivated to optimize their research output. This is further amplified by the potential gains or losses in prestige, as NCFHE publicly releases the annual evaluation results.

Remarkably, the demanding criteria introduced in 2016 have also proven to be the most enduring: unlike previous reforms, no subsequent measures have been taken to reverse them. Does this mean that the conflict over research reform finally subsided through a consensus among reformists and conservatives on the need to enhance Romania’s international scientific standing? To properly answer this question, we must further examine government budget allocations for research.

Government budget allocations for research

Romania’s ambitious reforms demanded significant resources but the Romanian government did not allocate the necessary funds. Figure 1 effectively illustrates this issue, showing the dynamics of Romania’s R&D expenditure as a percentage of the total government budget on the primary axis, and the national GDP on the secondary axis.

Government budget allocations for research have closely mirrored the GDP trajectory up to 2016. Post-1989, Romania’s GDP of $41.45 billion plummeted to a mere $25.12 billion in 1992 and remained stagnant for most of the 1990s. At the same time, there was a substantial decline in budget allocations for research. The path of European integration reversed the economic tide and this positive dynamic was mirrored in the upward trend of research expenditures that lasted until the global financial crisis from 2007 to 2009, which had a significant impact on Romania’s economic trajectory.

After 2015, Romania embarked on a new wave of sustained economic growth, reaching new historical heights with each passing year. Inexplicably, government allocations for research followed an opposing trajectory, declining from 0.81 in 2016 to 0.56% in 2017, 0.5% in 2018, and ultimately reaching a minimum of 0.3% in 2022. This figure represents the lowest budget national allocations for research in recent decades and is far below the EU average of 1.49% or the 1.02% average of the former communist EU countries. While the strong economic growth during this period mitigated the impact of the greatly reduced budget allocations, when adjusted for purchasing power standards (PPS), research spending decreased from 412.8 million PPS in 2015 to 367.5 million PPS in 2022 (Eurostat, 2023).

How did the 2016 research reform impact Romania’s scientific output?

The imposition of stringent hiring and promotion criteria has pressured both individual researchers and research institutions to increase their research output rapidly and significantly. Studies conducted in similar contexts have found that imposing hiring and promotion constraints to produce more indexed publications usually has the desired effect. For example, in Ukraine, the introduction of stricter requirements for academic promotion has led to an increase in research output, though there were also negative effects related to research impact (Abramo et al., 2023). In Eastern Europe, the pressure to publish more and better has contributed to a threefold increase in WoS-indexed publications in the fields of economics between 2000 and 2015 (Grančay et al., 2017).

However, the implementation of these policies has coincided with the start of a notable and persistent decline in annual government allocations for research and development. While existing evidence suggests that the relationship between research spending and research output at the national level may be complicated by spillover effects, the lag between investment and return, or by decreasing effects over time (Crespi & Geuna, 2008), it is generally agreed that countries cannot hope to increase their research output without being serious about their budget allocations (Courtioux et al., 2022).

The decline in government allocations for research took place in an environment characterized by very lenient official attitudes toward the social norms that uphold academic integrity and mitigate academic misconduct and corruption. This is a significant issue because incentives or constraints aimed at boosting research output can cause a range of questionable practices. For example, researchers may prioritize publishing in questionable journals, split their papers into smaller ones to artificially inflate their output, engage in self-citation tactics, and so forth (Elton, 2000; Franzoni et., 2011; Seeber et al., 2017). Such behaviors are not restricted to individual researchers, as journals, research institutions, and even governments may also act to game the metrics (Biagioli et al., 2019; Siler & Larivière, 2022).

In general, dishonest behaviors are more likely when the researchers, although aware of the nature of the questionable behaviors, are under heavy constraints to publish and are working in permissive environments, where the probability of getting punished is low and many people are building successful careers through dishonesty (Hall & Martin, 2019). The current situation appears to meet all these criteria.

Furthermore, whereas trade-offs between research output and research quality are a problem even in countries with well-established research systems, in countries with weaker systems large parts of their scientific output can suffer. As described above, during its post-communist transition, Romania’s research was published mostly in national journals or national journals disguised as international journals (Hladcenko & Moed, 2021). The repeated attempts at reform improved this situation and increased the international participation of Romanian researchers. However, there is evidence that a large proportion of the total scientific output has followed a path of least resistance, shifting from the excessive use of one convenient outlet to another. Specifically, it seems that, gradually, proceeding papers took the place previously dominated by national journals.

Proceeding papers, a specific type of scientific publication, are not inherently problematic and have served an important role in disseminating scientific findings in certain disciplines (González-Albo & Bordons, 2011). However, in some countries, their use has escalated beyond reasonable levels and into fields where they are not the primary conduit for scientific communication. According to a recent analysis, Bangladesh, Bulgaria, and Romania exhibit the most pronounced deviations from the global average in terms of the sheer number of proceeding papers published (Guskov & Kosyakov, 2023). Theoretically, the 2016 reform, which marginalized proceeding papers and shifted focus to WoS journals, should have resulted in a substantial decline in this type of publication as proceedings would have become less attractive for researchers seeking employment or promotion and for universities seeking improved funding. Notwithstanding this expectation, the data provided by Guskov and Kosyakov encompasses the 2017–2019 period, leaving open the possibility that the 2016 hiring and promotion criteria had minimal or no impact on discouraging research from publishing proceeding papers.

Recent evidence strongly suggests the post-2016 rise of a new accessible and affordable publishing outlet. A recent study found that in 2021 almost a third of all published WoS-indexed articles in Central and Eastern European countries were published in MDPI journals, with Romania and Poland recording the largest shares (Csomós & Farkas, 2023). According to the 2023 Journal Citation Reports this publishing group owns 208 journals with calculated impact factors and has expanded its global market share at a rapid pace, particularly in countries situated at the periphery or semi-periphery of international research. It charges relatively accessible publication fees and offers a much shorter turnaround time compared to other publishers. However, MDPI has garnered criticism for publishing a vast number of articles in special issues while keeping a low rejection rate (Crosetto, 2021; Knöklhemann et al., 2022), for its suspect citation practices (Oviedo-García, 2021), for strategically using declining journal quality for profit extraction (Siler & Larivière, 2023), and its largest mega-journal was recently delisted from WoS. Although such issues are not exclusive to this group and other publishers also provide fast publication, it is important to highlight that MDPI distinguishes itself by its significant regional presence. Notably, a third of its offices are situated in Romania, Serbia, and Poland, setting it apart from its competitors (Csomós & Farkas, 2023).

To resume, we have a situation where the principal asks the agents to produce more with less and has a long history of lenient and complicit attitude toward scientific integrity. Based on these simultaneous constraints and the existing data, we can build some likely scenarios of the effects of the 2016 research reforms.

Since recent evidence has shown that Romania stands out from the world average both in terms of proceeding papers and MDPI articles, it seems likely that Romanian researchers solved the post-2016 constraints by directing their research toward these affordable and accessible outlets. The financial support provided by universities to cover open-access publishing fees particularly supports the MDPI hypothesis. However, while the MDPI’s recent global expansion and its overrepresentation in Romania imply a certain post-2016 surge in the MDPI articles published by Romanian researchers, it remains unclear whether this growth has been accompanied by a similar increase in articles published in journals from other publishers and how it compares to the trajectory of proceeding papers.

In the first case, it seems reasonable to assume that simply covering the publication fees in open-science journals or awarding cash for publication in journals with a high impact factor can only get you so far (Vîiu & Păunescu, 2021). Without providing the resources necessary to cover the costs of more elaborate research projects it is hard to envision an increase in the number of high-quality studies needed to stand a chance for publication in top international journals.

In the second case, proceeding papers were encouraged until 2012–2013, strongly encouraged afterward, and sidelined by the latest reform. It is reasonable to expect researchers to prioritize meeting the mandatory criteria for hiring and promotion, which focus exclusively on articles. However, since proceedings have not been eliminated, they may still be considered valuable outlets for publication, albeit to a lesser extent. This means that they have either kept their pre-2016 levels or entered a period of decline.

Finally, we lack a clear understanding of how Romania’s research output stacks up against other countries. As mentioned above, recent years have witnessed a significant rise in research spending and publication. Romania’s decision to address this tough race by reducing research funding while simultaneously increasing the pressure to publish carries the potential for either significantly harming its research production or enabling it to maintain it at the expense of continuing to excessively use some research outlets or switching to new ones.

Data and methods

This study employs the synthetic control method to evaluate the impact of the 2016 reforms on Romania’s research output. The synthetic control method (SCM) is a valuable statistical tool for assessing the effects of aggregate interventions. It has been successfully employed to assess the effect of various socio-political events or interventions on economic outputs (Abadie, Diamond, & Hainmueller, 2015; Abadie & Gardeazabal, 2003) but also the impact of research policies on scientific output (Banal-Estañol et al., 2023).

The essence of SCM lies in constructing a counterfactual scenario that depicts the trajectory of the target unit in the absence of the intervention. This counterfactual is then compared to the actual post-intervention data to isolate the causal effect of the intervention. Unlike traditional comparative case studies, which rely on a subjective selection of comparison units and may not provide adequate matches for the intervention unit, SCM employs a data-driven approach that utilizes pre-intervention information on covariates and the outcome variable to create a weighted combination of control units that maximizes similarity with the intervention unit’s pre-intervention trajectory. It is this synthetic unit that serves as a counterfactual reference point for comparing the post-intervention outcomes of the intervention unit. When applying SCM it is important to consider both the context of the study and the nature of the data. Control units must be chosen carefully, as large discrepancies in the observed characteristics could result in biased estimates. For these reasons, it is recommended to select control units based on economic similarity, geographic proximity, or other relevant criteria and to avoid control units that have experienced significant idiosyncratic changes (Abadie, 2021).

Data

In the current case, the purpose is to test if the research reform implemented by Romania starting in 2016 had a significant impact on its scientific production. To achieve this goal, the current study uses the tidysynth R package (Dunford, 2023). Romania presents a contrasting profile in terms of scientific productivity and the relevant covariates incorporated into the analyses. For instance, based on WoS data, Romania ranks 41st in article production between 2010 and 2021, being outperformed by smaller countries, while placing 20th in proceeding papers, surpassing much larger or productive nations. Similarly, while classified as a high-income country, Romania falls well below the global average in education and research expenditures. Because some of these particularities are shared with other countries from the former Eastern Communist Bloc, while other characteristics are shared with countries outside the Bloc, the analyses will encompass both the global sample of 76 countries and a regional subset, composed of countries from the former Eastern Communist Bloc. The list of countries included in the global and regional datasets is presented in Table 1A in the Appendix.

The 2010–2015 period serves as the pre-intervention period, while the 2016–2021 period serves as the intervention period. Since varying trajectories are anticipated for distinct types of WoS documents, the analyses will focus on both overall scientific production, as reflected in WoS, and several key document types, namely articles, articles by publisher (MDPI articles and non-MDPI articles), and proceeding papers. The analyses will include the following covariates: population (log-transformed), gross domestic product per capita, research expenditure, education expenditure, corruption, political stability, rule of law, brain drain, economic inequality, and percent of urban population, plus the mean research output across the pre-intervention years.

Results

Descriptives

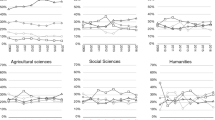

This section initially compares Romania’s scientific output against the averages of the global and regional datasets. Figure 2 depicts (a) total scientific production, (b) article production, (c) MDPI-published articles, (d) articles published by publishers other than MDPI, and (e) proceeding papers. To make the trajectories of lower-value subsets more visible, the y-axis reflects the average growth rate of scientific production relative to 2010. The values on which these charts are based are described in Table A2 of the Appendix.

The charts in Fig. 2 reveal Romania’s significant deviation from the global and regional patterns of scientific output growth. Notably, Romania’s trajectory diverges from that of other countries starting in 2016, exhibiting distinct patterns in total scientific output, MDPI articles, and proceeding papers. In the first case, Romania’s total output experiences a decline, a trend that stands in stark contrast to the overall upward trajectory observed in the global and regional averages. In the second and third cases, Romania’s production experiences a strong surge in MDPI articles but a fall in proceeding papers. This plunge is also evident in other countries, albeit with a lag. The reason why previous studies found Romania to rank significantly above the global average in proceeding papers production between 2017 and 2019 is that Romania started its decline in 2016, before other countries, but the decline began from a very high base (8,156 proceeding papers in 2015).

Interestingly, Romania also diverges in terms of the total article and non-MDPI article production, but this divergence begins after 2013. This suggests that the earlier dissolution of reformist research policies might have played a significant role in driving this divergence. Accordingly, the SCM analysis will also consider a scenario where the pre-intervention period extends from 2010 to 2013.

Romania’s trends are least dissimilar to those exhibited by its regional group. The ex-communist group exhibits a lower growth rate for total scientific output, articles, and non-MDPI articles than the global average. Conversely, the regional group demonstrates a higher growth rate for MDPI articles and, until 2017, for proceeding papers.

Proceeding papers exhibit the most divergent trajectories compared to other WoS document types. While all other indicators consistently increased in both comparison groups, proceeding papers experienced a period of growth until around 2017, followed by a decline.

Main results

The SCM results are presented in Fig. 3 and Table 1. Because a pre-intervention period ranging from 2010 to 2013 provided a better fit to the data when focusing on the total article and non-MDPI article production (i.e., the weighted combination of control units tracked the pre-intervention trajectory of the intervention unit more closely), these are the synthetic estimates depicted in the charts and the table. For all the other cases, the pre-intervention period is 2010–2015. For comparison purposes, Figure A1 from the Appendix depicts the SCM estimation for the total and non-MDPI article production when considering 2010–2015 as the pre-intervention period.

The findings support the notion that Romania’s recent research reforms have had a detrimental impact on its scientific output. The data show a discrepancy of 36,444 documents between the projected and actual scientific productions over the intervention period. This suggests that Romania’s scientific output might have been 31.21% higher had it maintained its pre-intervention growth trend.

This figure is quite close to the 29.85% difference observed when making the comparison with the regional synthetic output. In both cases, the discrepancy is not distributed uniformly across the six years of the intervention. On the contrary, consistent with the idea of a cumulative effect of reduced funding, it increased from 13.18 in 2016 to 62.72% in 2021 for the global synthetic comparison, and from 17.52 to 49.82% for the regional synthetic comparison. This overall trend is qualified by its components.

An important component of the downward trend of Romania’s total output was the strong decline of proceeding papers, which fell from a maximum of 8156 in 2015 to just 1853 in 2021. However, the synthetic controls, particularly the regional one, only differed from actual production between 2016 and 2019, after which they also recorded a similar plunge. Romania simply started this downward trend earlier than others but was eventually caught up. This is also reflected in the fact that placebo testing for this document type did not generate root mean squared prediction error ratios that put Romania in the top position (see Table 3A in the Appendix). Therefore, the observed changes in total output cannot be exclusively linked to the reduction in proceeding papers.

The bigger issue lies with article production. Romania’s production of MDPI articles has increased at an astonishing rate, from 101 in 2016 to 3434 in 2021, well above the increase observed in the global synthetic control, which goes from 95 to 1908, but below the growth observed in the regional synthetic control, which goes from 106 to 4735. It should be noted that the larger values of the later synthetic group suggest an opposite situation than the one recorded by the comparison with the actual averages. The reason for this contrast is that the SCM algorithm attributed the most important weights to Serbia and Poland, which had larger growth rates of MDPI articles than Romania (Table 3A in the Appendix describes all SCM weights).

However, and this is the most crucial aspect, the analysis of the complete sample reveals that, while actual MDPI articles published worldwide in 2021 accounted for an average of 19.76% of the surplus of total articles published in 2021 compared to 2013, ranging from 4.09 to 59.48%, Romania’s corresponding figure was a staggering 98.46%, far surpassing any other country. This implies that Romania’s overall article output significantly diminishes when not considering MDPI journal articles. Indeed, the difference between Romania’s 2021 and 2013 non-MDPI article production is just 53.

This is reflected in charts (b) and (d) of Fig. 3, which demonstrate a greater disparity between actual production and the global counterfactual for non-MDPI articles than for overall article production. Even the regional synthetic control for non-MDPI articles, based on nations with strong increases in MDPI articles, is still well above actual Romania: the regional synthetic and actual outputs diverge by 23,979 documents in non-MDPI article production throughout the entire intervention period, suggesting that Romania’s output could have been a substantial 29.21% larger. The corresponding figures for the global synthetic control, where the publication of articles in MDPI journals is less remarkable, are 30,648 and 37.33%, respectively.

Thus, the substantial production of MDPI articles by Romanian researchers has not effectively countered the increasing deficit of articles published elsewhere. This, coupled with the fact that the rise in MDPI articles amounts to approximately half of the decline in proceeding papers, helps explain the discrepancies observed in overall scientific output. While a clear shift from proceeding papers to MDPI articles can be observed starting in 2016, the reforms implemented in that year have been unsuccessful in stimulating the publication of non-MDPI articles, which has plateaued since 2013. In contrast, Romania’s regional peers, who also had a strong increase in MDPI articles and a strong decrease in proceeding papers managed to increase their non-MDPI article production.

These main results are also observed when conducting the SCM analysis using output indicators adjusted by country population (see Fig. 2A in the Appendix).

Discussion and conclusion

This study examined if a highly unusual research policy mix, namely Romania’s recent research reforms, which sharply increased publication quotas while reducing government research allocations, has had a detrimental impact on research output. Previous research showed that increasing publication quotas generally has a positive effect on scientific production quantity (Abramo et al., 2023; Grančay et al., 2017), whereas reduced funding has a negative effect (Courtioux et al., 2022). Consequently, the study anticipated two possible outcomes: either a drop in scientific production or growth achieved at the expense of diverging from global norms by placing, yet again, excessive emphasis on a specific publishing outlet. The results support both scenarios.

Post-reform, proceedings papers plummeted while MDPI journal articles surged significantly. The first results appear to contradict earlier research by Guskov and Kosyakov (2023), which highlighted Romania's significant deviation from the global average in terms of the volume of proceeding papers published. However, the contradiction is only apparent. Although there has been a noticeable decline in Romania’s publication of conference papers since 2016, the country still ranked higher than many others between 2017 and 2019. This is attributable to its substantial initial volume. In 2015, Romania was the 15th highest country globally in proceeding papers, surpassing many larger nations. On the other hand, the other result is in line with recent findings showing that MDPI plays a dominant role in the overall scientific article output of Central and Eastern European countries (Csomós & Farkas, 2023).

Besides this divergent trend in proceeding papers and MDPI articles, publications in journals from other publishers remained stagnant. So much so, that the increase of MDPI articles in 2021 compared to 2013 accounts for 98.46% of the increase in total article output, by far the largest figure in the entire global sample of 76 countries. However, as the numeric rise in MDPI articles pales in comparison to the decline in proceedings papers, overall scientific output diminished greatly compared to the rest of the world. The synthetic controls built on global and regional samples of countries both suggest that Romania’s overall scientific production could have been approximately 30% higher in the absence of the reforms.

Interestingly, while most indicators changed after the 2016 reforms, the stagnation of non-MDPI articles seems to have started after 2013, that is after the undoing of the penultimate reform aimed at increasing national WoS article output. Why did Romania’s non-MDPI article output fall behind other countries after 2013 and continue to do so after 2016? Besides the obvious effect of reduced funding, another important factor could be that the Romanian authors simply did not have to publish in WoS-index journals between 2013 and 2015 or in non-MDPI journals afterward. Both individual institutions and national agencies actively incentivized researchers to publish proceeding papers and, subsequently, MDPI articles, potentially leading to a ‘read between the lines’ approach among many. It is also possible that the post-2016 decrease in research funding selectively affected the best-performing universities and research institutions, which were winning most of the research grants and were thus most able to publish in the most prestigious international journals. This is an issue that has to be addressed by future research.

The situation described here does not reflect the failure of a well-thought-out set of research policies. No theory and no existing evidence recommend such a policy mix. Rather, it seems more likely to reflect the continuation of a fundamentally dishonest position, based on preaching alignment with global best practices while overlooking the most significant deviations from academic quality and integrity and failing to allocate adequate resources and distribute them based on sound productivity criteria. In recent decades Romania has seen several instantiations of such wink-wink approaches and, unfortunately, its latest set of policies only served to replace one excessive publication habit with a new one. The outcomes discussed here demonstrate the harmful impacts observed before on both individual and institutional research actors when stringent publication demands coincide with lenient regulatory environments (Biagioli et al., 2019; Hall & Martin, 2019; Siler & Larivière, 2022).

In conclusion, these findings underscore the importance of clear and consistent government policies in supporting research activities. Vague and contradictory signals about academic goals and fluctuating funding levels can erode research integrity, hinder long-term planning, and ultimately impede research progress. Romania’s experience should serve as a cautionary tale for other countries half-heartedly seeking to overcome historical research development gaps.

As for Romania itself, some of the consequences of the policies discussed here have gained public attention, ruining crucial national ambitions. In 2016, Romania had two universities close to entering ARWU’s top 500 and was hoping that more would follow suit. Not surprisingly given the SCM results outlined here, these aspirations were dashed in 2023 as not a single Romanian university managed to secure a position within ARWU’s top 1000. Rather than acknowledging this setback and engaging in a thorough analysis of the underlying causes, key decision-makers have resorted to perpetuating unrealistic narratives. For instance, despite overseeing a period of historically low national research funding and lacking any compelling justifications, Romania’s Research Minister continued to express ambitious goals, aspiring to regional leadership and placing the country among the global top 10 in specific domains (Hotnews, 2023). These reactions suggest that Romania’s journey towards responsible and effective research policies remains complicated and challenging. To achieve this objective, the country requires coherent, equitable, and realistic actions, resource allocation aligned with research goals, and a robust overlap between the explicit and implicit aspects of the enforced academic norms and guidelines.

References

Abadie, A. (2021). Using synthetic controls: Feasibility, data requirements, and methodological aspects. Journal of Economic Literature, 59, 391–425. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20191450

Abadie, A., & Gardeazabal, J. (2003). The economic costs of conflict: A case study of the Basque country. The American Economic Review, 93, 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282803321455188

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2010). Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105, 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2009.ap08746

Abbott, A. (2012). Romanian scientists fight plagiarism. Nature, 488, 264–265.

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Hladchenko, M. (2023). Assessing the effects of publication requirements for professorship on research performance and publishing behaviour of Ukrainian academics. Scientometrics, 128, 4589–4609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04753-y

Babeș Bolyai University (2023). Seed grants guide. Retrieved February 14, 2024, from https://www.ubbcluj.ro/ro/infoubb/files/InfoUBB_2020_10/2020_10_12_HCA_15100_privind_Ghidul_de_accesare_și_utilizare_a_granturilor_de_tip_seed_din_Fondul_de_Dezvoltare_UBB_2020.pdf

Banal-Estañol, A., Jofre-Bonet, M., Iori, G., Maynou, L., Tumminello, M., & Vassallo, P. (2023). Performance-based research funding: Evidence from the largest natural experiment worldwide. Research Policy, 52, 104780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104780

Biagioli, M., Kenney, M., Martin, B. R., & Walsh, J. P. (2019). Academic misconduct, misrepresentation and gaming: A reassessment. Research Policy, 48, 401–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.10.025

Boia, L. (2001). History and myth in the romanian consciousness. Central European University Press.

Cattaneo, M., Meoli, M., & Signori, A. (2016). Performance-based funding and university research productivity: The moderating effect of university legitimacy. The Journal of Technological Transfer, 41, 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-014-9379-2

Checchi, D., Malgarini, M., & Sarlo, S. (2019). Do performance-based research funding systems affect research production and impact? Higher Education Quarterly, 73, 45–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12185

Civera, A., Lehmann, E. E., Paleari, S., & Stockinger, S. A. E. (2020). Higher education policy: Why hope for quality when rewarding quantity? Research Policy, 49, 104083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104083

Courtioux, P., Métivier, F., & Rebérioux, A. (2022). Nations ranking in scientific competition: Countries get what they paid for. Economic Modelling, 116, 105976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2022.105976

Crespi, G. A., & Geuna, A. (2008). An empirical study of scientific production: A cross country analysis, 1981–2002. Research Policy, 37, 565–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.12.007

Crosetto, P. (2021). Is MDPI a predatory publisher? Retrieved February 14, 2024, from https://paolocrosetto.wordpress.com/2021/04/12/is-mdpi-a-predatory-publisher/

Csomós, G., & Farkas, J. Z. (2023). Understanding the increasing market share of the academic publisher “multidisciplinary digital publishing institute” in the publication output of central and Eastern European countries: A case study of Hungary. Scientometrics, 128, 803–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-022-04586-1

Docampo, D., & Cram, L. (2017). Academic performance and institutional resources: A cross-country analysis of research universities. Scientometrics, 110, 739–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2189-6

Dunford, E. (2023). Tidysynth: A tidy implementation of the synthetic control method. https://github.com/edunford/tidysynth.

Ebadi, A., & Schiffauerova, A. (2016). How to boost scientific production? A statistical analysis of research funding and other influencing factors. Scientometrics, 106, 1093–1116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1825-x

Eisemon, T. O., Ionescu, S. I., Davis, C. H., & Gaillard, J. (1996). Reforming romania’s national research system. Research Policy, 25, 107–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(94)00823-X

Elton, L. (2000). The UK research assessment exercise: Unintended consequences. Higher Education Quarterly, 54, 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2273.00160

Eurostat (2023). Eurostat database. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database.

Florian, R., & Florian, N. (2006). Majoritatea revistelor științifice românești nu servesc știința [The majority of romanian scientific journals do not Serve Science]. Ad. Astra, 5. http://www.ad-astra.ro/journal/9/florian_reviste_locale.pdf.

Florian, R. (2004). Migratia cercetatorilor romani. Situatia actuala, cause, solutii. Știința [The migration of romanian researchers. current status, causes, and solutions]. Ad Astra, 3. http://www.adastra.ro/journal/6/florian_migratia.pdf.

Franzoni, C., Scellato, G., & Stephan, P. (2011). Science policy. Changing Incentives to Publish. Science, 333, 702–703. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1197286

Geuna, A., & Martin, B. R. (2003). University research evaluation and funding: An international comparison. Minerva, 41, 277–304. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MINE.0000005155.70870.bd

Ghiațău, R. M. (2021). Fighting academic dishonesty in romanian universities: Lessons from international research. In A. W. Wiseman (Ed.), Annual review of comparative and international education 2020. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited: International Perspectives on Education and Society.

Gonzalez-Albo, B., & Bordons, M. (2011). Articles vs. proceedings papers: Do they differ in research relevance and impact? A case study in the library and information science field. Journal of Informetrics, 5, 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2011.01.011

Grančay, M., Vveinhardt, J., & Šumilo, Ē. (2017). Publish or perish: How central and Eastern European economists have dealt with the ever-increasing academic publishing requirements 2000–2015. Scientometrics, 111, 1813–1837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2332-z

Guskov, A. & Kosyakov, D. (2023). Country shifts in the authorship of conference papers. 27th International Conference on Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators. https://doi.org/10.55835/643fadb94e97d59d99bef125.

Hall, J., & Martin, B. R. (2019). Towards a taxonomy of research misconduct: The case of business school research. Research Policy, 48, 414–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.03.006

Hladchenko, M., & Moed, H. F. (2021). The effect of publication traditions and requirements in research assessment and funding policies upon the use of national journals in 28 post-socialist countries. Journal of Informetrics, 15, 101190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2021.101190

Hotnews (2023). Ministrul cercetării: visul meu e ca românia să devină lider în regiune și top 10 mondial prin tehnologiile viitorului [research minister: my dream is for romania to become the leader in the region and top 10 in the world in the technologies of the future]. retrieved February 14, 2024, from https://www.hotnews.ro/stiri-politic-26724880-ministrul-cercetarii-visul-meu-romania-devina-lider-regiune-top-10-mondial-prin-tehnologiile-viitorului.htm.

Ives, B., Alama, M., Mosora, L. C., Mosora, M., Grosu-Radulescu, L., Clinciu, A., Cazan, A., et al. (2017). Patterns and predictors of academic dishonesty in Romanian university students. Higher Education, 74(5), 815–831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0079-8

Judt, T. (2005). Postwar: A history of Europe since 1945. Penguin Books.

Knöchelmann, M., Hesselmann, F., Reinhart, M., & Schendzielorz, C. (2022). The rise of the guest editor-discontinuities of editorship in scholarly publishing. Frontiers Research Metrics and Analytics, 6, 748171. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2021.748171

Lepori, B., Masso, J., Jabłecka, J., Sima, K., & Ukrainski, K. (2009). Comparing the organization of public research funding in Central and Eastern European countries. Science and Public Policy, 36, 667–681. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234209X479494

Lin, P. H., Chen, J. R., & Yang, C. H. (2014). Academic research resources and academic quality: A cross-country analysis. Scientometrics, 101, 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1362-z

Linz, J. J., & Stepan, A. (1996). Problems of democratic transition and consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and post-communist Europe. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Martin, B. R. (2011). The research excellence framework and the “impact agenda”: Are we creating a Frankenstein monster? Research Evaluation, 20, 247–254. https://doi.org/10.3152/095820211X13118583635693

National Council for the Financing of Higher Education (2023). Data on 2023 university financing. Retrieved February 14, 2024, from http://www.cnfis.ro/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/FI2023preliminar_site.pdf.

National Institute of Statistics (2023). Tempo online. Available at http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/.

National Science Foundation (2022). Research and development: U.S. trends and international comparisons. science and engineering indicators 2022. NSB-2022–5. Alexandria, VA. Available at https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20225/.

Oviedo-García, M. Á. (2021). Journal citation reports and the definition of a predatory journal: The case of the multidisciplinary digital publishing institute (MDPI). Research Evaluation, 30, 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvab020

Pajic, D. (2015). Globalization of the social sciences in Eastern Europe: Genuine breakthrough or a slippery slope of the research evaluation practice? Scientometrics, 102, 2131–2150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1510-5

Păunescu, M., Gheba, A., & Jitaru, G. (2022). Performance-Based Funding—the romanian experience of the last five years (2016–2020). In A. Curaj, J. Salmil, & C. M. Hâj (Eds.), Higher education in Romania. Cham Springer: Overcoming challenges and embracing opportunities.

Seeber, M., Cattaneo, M., Meoli, M., & Malighetti, P. (2019). Self-citations as strategic response to the use of metrics for career decisions. Research Policy, 48, 478–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.12.004

Siler, K., & Larivière, V. (2022). Who games metrics and rankings? Status, institutional logics and journal impact factor inflation. Research Policy, 51, 104608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104608

Siler, K., & Larivière, V. (2023). Varieties of diffusion in academic publishing: How status and legitimacy influence growth trajectories of new innovations. The Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24844

Stan, L., & Turcescu, L. (2004). Politicians, intellectuals, and academic integrity in Romania. Problems of Post-Communism, 51, 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2004.11052175

Tarlea, S. (2017). Higher education governance in central and Eastern Europe: A perspective on Hungary and Poland. European Educational Research Journal, 16, 670–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116677756

Teodorescu, D., & Andrei, T. (2011). The growth of international collaboration in East European scholarly communities: A bibliometric analysis of journal articles published between 1989 and 2009. Scientometrics, 89, 711–722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0466-y

Tismăneanu, V. (2003). Stalinism for all seasons: A political history of romanian communism. University of California Press.

Vîiu, G. A. (2015). Quality-related funding in romanian higher education throughout 2003–2011: A global assessment. The Romanian Journal of Society and Politics, 10, 26–59.

Vîiu, G. A., & Păunescu, M. (2021). The citation impact of articles from which authors gained monetary rewards based on journal metrics. Scientometrics, 126, 4941–4974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-03944-9

Vlăsceanu, L. & Hâncean, M. G. (2015). Policy incentives and research productivity in the Romanian higher education. An institutional approach. In: Curaj, A., Matei, L., Pricopoie, R., Salmil, J., and Scott, P. (Eds) The European higher education area. Cham: Springer.

Waligóra, A., & Górski, M. (2022). Reform of higher education governance structures in Poland. European Journal of Education, 57, 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12491

World Bank (2023). World Bank Indicators. Retrieved on October 17 from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator.

Zacharewicz, T., Lepori, B., Reale, E., & Jonkers, K. (2019). Performance-based research funding in EU member states–A comparative assessment. Science and Public Policy, 46, 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scy041

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there exists no competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

About this article

Cite this article

Cernat, V. The unprincipled principal: how Romania’s inconsistent research reform impacted scientific output. Scientometrics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-05118-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-05118-9