Abstract

This country case study describes how science policy instruments are designed to shape publication patterns and identifies the changes in researchers’ productivity that can be observed over the period 2009–2016 in Poland by analysing data on 452,277 publications submitted to the country’s national research evaluation system. Our analysis reveals that policy instruments used in the country’s national research evaluation system, academic promotion procedures and competitive grants have increased the number of articles with an impact factor without compromising publication quality, as measured by a bibliometric indicator. Our findings highlight that only clear and stable incentives have influenced researchers’ publications. Therefore, patterns in scholarly book publications—for which regulations were not clear and stable—have not been significantly shaped by science policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Policy makers implement numerous policy instruments to stimulate world-class science and education, and to foster innovation at the national level, yet the question of how such science policy instruments shape and actually affect the production of knowledge and the dissemination of research results still remains unanswered, despite the various theoretical frameworks and empirical studies that have been proposed and conducted (Butler 2005; Schneider et al. 2016; van den Besselaar et al. 2017). Further, some studies argue that a single cause for the growth in publications recorded in international databases cannot be traced (Jiménez-Contreras et al. 2003), with a variety of factors needing to be investigated further (Pajić 2015).

In this paper, we understand shaping the dissemination of research as shaping the publication patterns of a given researcher, institute or discipline. These patterns are described in the types of publications (e.g. articles, scholarly books, patents), collaboration patterns and other indicators relevant to scholarly publications. In the sciences, publication patterns are shaped through a variety of factors depending on the discipline (Engels et al. 2012), such as epistemic cultures (Knorr Cetina 1999), citation cultures (Wouters 1999) and the growing importance of interdisciplinary research and cooperation (Levitt and Thelwall 2016). These factors are integral to science and research, and substantially influence what type of publications are favoured, what publication language is most often used, how many authors prepare publications, and which journals in a given discipline are acknowledged by the academic community as a valid way of communicating research results.

Science policy serves to achieve a number of goals that are important to society, the economy or to science itself. One of the most commonly used instruments of science policy is research evaluation. Ex post evaluation is conducted at the levels of individual researchers, higher education institutions, disciplines or regions, whereas ex ante evaluation is most often used to assess research project proposals. In all types of evaluations, publications are the key indicator through which researcher productivity and excellence or the impact of the research are assessed (Aksnes et al. 2012; Kulczycki 2017). The aim of research evaluation is very often connected to science policy goals. One such goal is to improve the productivity of researchers, such as by increasing the number of publications with an international author. Research evaluation may also facilitate the distribution of funding across institutions in a given country.

In general, it can be agreed that the level of public R&D funding is the most important instrument in shaping research activities at the institutional (Henriksen and Schneider 2014) and individual levels (Franzoni et al. 2011). Other mechanisms, such as different models of university governance, competitive grants and promotion procedures, also influence publication patterns to some extent. The instruments which focus on the productivity of researchers can have both positive and negative consequences on research practices. For example, such instruments can increase the number of publications in top-tier channels but, at the same time, can push researchers into conducting some questionable practices (Aagaard and Schneider 2017; Bal 2017). Nonetheless, there are no easy answers to the question of how science policy actually shapes publication patterns, due mostly to the complexity of the research and the policies themselves.

Policy makers design incentives to support the transformation of publication patterns and researcher behaviours. The incentive to publish first and foremost in international journals became common in the 1980s. Incentives to publish can be direct, such as the monetary reward systems in Mexico (Neff 2017) and China (Quan et al. 2017); as per these systems, if a researcher publishes in a way promoted by an incentive, they can receive extra funding or a larger salary. Not only do direct cash incentives influence how researchers publish their results, but can also affect career incentives (e.g. tenure in the U.S. or various national academic promotion procedures in European countries), with the evaluation of proposals for competitive grants also influencing publication patterns (Franzoni et al. 2011).

There are also two other types of instruments that incentivise institutions to transform the publication patterns of their academic staff members. The first is the performance-based research funding system (PRFS), which is often combined with a country’s research evaluation system at a national level (Hicks 2012; Kulczycki et al. 2017; Sivertsen 2016). Such systems operate in the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Poland and the United Kingdom. In these systems, bibliometric indicators serve to incentivise specific publication channels (e.g. journal articles have more weight than book chapters), languages, or by regulations on publication counting, cooperation across institutions and countries. Institutions are funded (fully or partially) on the basis of the results of research evaluation. Thus, changing publication patterns to improve the results and obtaining more funding has become one of the strategic goals of many institutions to bring direct funding to those institutions. The second instrument emphasises prestige distribution rather than financial incentives. Such an instrument can be observed in Australia where the national research evaluation framework (Excellence in Research for Australia) has shifted from a PRFS instrument to one that assesses the excellence and impact of the research. The results of this framework have no direct financial consequences.

Discussions on the effects of science policy on publication practices have focussed on a single discipline (Neff 2017), an institution (Hammarfelt and de Rijcke 2015), or countries (Aagaard 2015; Aagaard and Schneider 2017; Schneider et al. 2016). One of the first such studies showing the consequences of science policy on publication patterns at the national level was Butler (2003), analyzing Australia’s increased proportion of publications indexed in the Science Citation Index and showing that even with an increase in publications in top-tier journals, citation impact declined. Some years later, van den Besselaar et al. (2017) extended Butler’s analysis and then argued that the output-based research funding in Australia had a positive effect on research quality. Butler’s response (2017) to the contradiction highlighted that van den Besselaar et al. (2017) was inaccurate and misrepresented several of Butler’s (2003) original statements.

Neff (2017), in investigating the Mexican situation, showed that the system of monetary incentives had increased productivity (more publications in top-tier journals) but, at the same time, had undermined Mexico’s ability to benefit from ecological research conducted by Mexican researchers. That study was criticised by Williams and Morrone (2018), who argued that the system has actually strengthened the quality of science at regional, national and international levels. Neff (2018) replied, stating that what the Mexican incentive system primarily does is unintentionally influence the research agenda of Mexican scholars.

So, in this paper, we aim to advance knowledge in regard to the effects of science policy on publication patterns, with specific respect to the Polish policy regimes. To this end, we reconstruct the goals and instruments of science policy in Poland and analyse the data from the Polish research evaluation system in the period 2009–2016 in all fields of science. We investigate how the country-level science policy shaped publications patterns over the last decade through PRFS incentives included. In our view, in the analysis of the long-term outcomes of the policies, it was not possible to investigate isolated factors and determine how they actually influenced the effects. Rather, we assume that understanding the historically determined social, economic and cultural contexts allows us to describe and detail the interacting network of factors that shaped the publication practices.

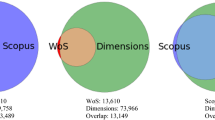

Science policy in Poland

The Polish case might be interesting for several reasons. First, Poland is one of the countries that underwent a democratic transition at the end of the previous century, and had to design an entirely new science policy. Secondly, for almost three decades Poland has used a performance-based funding system, which for over a decade implemented direct incentives regarding publication patterns. Finally, Poland is one of the biggest European countries that collects and uses full (not only indexed in the Web of Science [WoS] or Scopus) bibliographic information in their national research evaluation system. Thus, investigating what science policy instruments have been implemented and analysing changes in publication patterns may shed more light on how science policy shapes researcher publication practices.

Starting point and the context: democratic transition and teaching mission

After World War II, Poland entered the communist bloc. The aim of research then in all fields was to develop a socialistic economy and society. This aim was to be achieved through central planning of all research activities, topics and resources. The evaluation of the sciences was not perceived as a way to assess the quality of research, but rather as a tool to verify whether plans had been realised (Balazs et al. 1995).

The transition from this communist legacy to a democratic state influenced science funding and organisation from 1989 (Heinecke 2016, 2017; Jablecka 1995), after which the new socio-economic situation shaped new roles for higher education and science systems. On one hand, the higher education system evolved from an elite into an egalitarian system by, among others, strong privatisation of the system, which included boosting the 403,824 students in 1990 to 1,953,832 students in 2005 (Kwiek and Szadkowski 2018). On the other hand, research and science systems lost their important role in universities. The teaching orientation was predominant even at the top public research-intensive universities, especially within the social sciences and humanities (SSH) faculties. The massive expansion of higher education and the focus on the teaching mission made it so that 30–40% of the academics from the public sector (SSH) held parallel employment in the private sector during the expansion period (the peak was in 2005). Moreover, in the early 90 s, the economic crisis and the bankruptcy of many enterprises of the previous century broke down the many of the long-established industry-academia relationships.

As a consequence, universities abandoned their research mission from the 1990s to the mid-2000s, and Polish scholarly publications lost their international visibility (Kozak et al. 2014). In 1990, in the Polish higher education system there were 403,000 students and 112 institutions (11 universities), whereas in 2016 there were 1.35 million students and 390 institutions, of which 19 were universities (Główny Urząd Statystyczny 2017). The number of R&D personnel increased from 47,433 full-time equivalents in 1994 to 82,594 in 2015 in all sectors in Poland (Eurostat 2018).

Re-institutionalisation of the research mission: waves of reform since 2009

In 2008 the Ministry of Science and Higher Education presented the policy statements “Building on Knowledge” (2008a) and “Strategy for Development of Science in Poland until 2015” (2008b), which initiated large-scale reforms of the science and higher education sector. The reconfiguration of the system was intended to restore the research mission at Poland’s institutions of higher education (Kwiek 2014). The Ministry focused on four strategic goals: (1) raising the level and effectiveness of science in Poland and increasing its contribution in world science, (2) enhancing the use of science for national education and culture and raising the country’s civilisation level, (3) stimulating innovation in the Polish economy, and (4) achieving closer integration with the European Research Area.

Throughout the period 2009–2016 there have been various regulations and incentives to promote publishing in journals with an impact factor. The strategic goals of the Polish science policy have been translated into various instruments. Incentives for the first goal were expressed by (1) highlighting the importance of publications in the Journal Citation Reports within the national research evaluation system, academic promotion procedures and competitive grants; (2) assigning in the national evaluation more points to publications written in English than in other languages; and (3) limiting the number of publications that could be submitted to the national evaluation exercise, which motivated the scientific units to focus on collecting better publications (in terms of obtained points) rather than more publications. For the second goal, a special ministerial programme for funding projects in the humanities was established. The third goal was incentivised by emphasising publications in the JCR and not limiting the number of patents that could be submitted for assessment in the national evaluation. Finally, achieving the fourth goal was incentivised by focusing on publications in English and publications in the JCR within the national evaluation.

Three aspects of the 2009–2012 reforms were found to be actual game changers. The first such was establishing the Committee for Evaluation of Scientific Units (KEJN), which designs and conducts the evaluation of universities and research institutions. The second such was moving various mechanisms of funding from the state level to the intermediary level of the new agencies (Woźnicki 2013): the distribution of grant funding for basic and applied sciences was moved to the National Science Centre (NCN) and the National Centre for Research and Development (NCBR), respectively. The other game changer was introducing updated rules of academic promotions, especially for obtaining a habilitation degree (the scientific degree obtained after a PhD), which included an official list of scientometric criteria.

Institutional evaluation and its publication-oriented instruments

Evaluation in Poland is conducted at the level of a ‘scientific unit,’ such as an institution of higher education, a unit within an institution of higher education (e.g. a faculty), a research institute, or an institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences. Each institution submits publications of its academic staff member, and for each submitted publication (an evaluation item), the given scientific unit obtains a specified number of points. The number of points depends on various factors, including the type of publication channels, publication language and the number of authors. During the last three cycles of evaluation, the range of points assigned to the same publication types was changed several times.

Apart from publications, data concerning several other parameters were gathered for the purposes of the evaluation exercise (Kulczycki et al. 2017). These parameters were aggregated into four main criteria, which were later weighted and summed. As a result, the position of a scientific unit was determined among similar units in terms of scientific discipline. Based on the position of the unit in the ranking, a scientific category (A+, A, B or C) was assigned by the Ministry. Ultimately, the scientific category translated into the size a block grant from the Ministry. The block grants in case of units from universities is about 10% of their annual budget, while for basic and applied research institutes it is up to 30% of their annual budget.

Table 1 presents a comparison of science policy instruments related to publication patterns implemented in the regulations over the last three evaluation cycles. We focus on bibliometric indicators, publication counts, and patents.

Other national instruments focused on publication patterns

Via the 2009–2012 reforms, two other instruments were implemented:

-

1.

Mechanisms of the NCN in Poland:

-

a.

Since the very first call for proposals in March 2011, researchers presenting their research portfolio are obliged to provide the values of their h-indexes and the total number of citations: researchers from the hard sciences must use the WoS Core Collection, whereas researchers from the soft sciences must use either WoS or Scopus (they can also use other sources, such as Google Scholar).

-

b.

Researchers must provide bibliographic information for up to 10 publications from the last 10 years with the number of citations (without self-citations) for each publication. Where it is possible, a 5-year journal impact factor for journals must be provided.

-

a.

In the era before the NCN, grant proposals were submitted to the State Committee for Scientific Researchers and later to the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, which officially did not use any bibliometric indicators for the required bibliographic records of publications (Antonowicz et al. 2017).

-

2.

Assessment criteria in the habilitation procedure:

-

a.

In September 2011, the Ministry of Science and Higher Education established for the very first time detailed criteria of assessment for candidates for a habilitation degree. The old rules ran parallel to the new one (i.e. established in September 2011) until September 2013.

-

b.

Candidates from the humanities and the arts must list their publications that are indexed in the WoS or the ERIH. For candidates from social sciences, these publications must be listed in the JCR or the ERIH. For candidates from the hard sciences, these publications must be listed in the JCR. Additionally, candidates must present the values of three bibliometric indicators on the basis of the WoS: citations, h-index and the Total Impact Factor [whose formula is similar to the ‘total impact’ (Beck and Gáspár 1991) and the ‘author impact factor’ (Pan and Fortunato 2014)].

-

a.

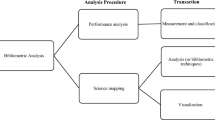

Data and methods

Dataset

A complete data set from the previous two cycles of evaluation was used in our analysis. During the evaluations, all scientific institutions submitted a questionnaire along with bibliographical records of publications and patents affiliated with those units for the periods 2009–2012 and 2013–2016. Each bibliographical record or patent submitted by an institution is called an evaluation item. From the perspective of a given institution, an evaluation item always refers to a ‘publication’, therefore in presenting our results, we use the term ‘publications’.

In Poland, an adaptation of whole counting of publications was used (Kulczycki 2017). A publication authored by three scholars from three different Polish scientific units was submitted separately by each of those units. Thus, in the final dataset, there were three evaluation items (bibliographical records) for one publication. All data concerning publications are aggregated in the same way as in the evaluation, that is, using the whole counting method.

For the 2009–2012 period, scientific units submitted 532,343 evaluation items related to publications and 4503 items related to patents, while for the 2013–2016 period they submitted 581,106 and 5932 items, respectively. The full-time equivalent of academic staff members in the first period was 82,867.09 and in the second period 86,461.84.

As discussed in the previous section, the evaluation assessed a limited number of evaluation items related to publications; i.e. 3N − 2N0, where N is the annual arithmetic mean of the full-time equivalent (FTE) of academic staff members who worked in a scientific unit during the evaluated period, and N0 is the FTE of academic staff members not publishing during the evaluated period. The result of the 3N − 2N0 formula presents the number of slots that can be filled by evaluation items. One evaluation item (i.e. publication) can take one slot, three-quarters of a slot or half a slot depending on the number of authors from the submitting institutions (see Table 1 for further details). The number of assigned points to a publication is multiplied by the amount of slot space taken.

In our analysis, therefore, we use the evaluation items that meet the following criteria: (1) were affiliated with researchers who were academic members of scientific institutions to which they affiliated publication; (2) were accepted by the experts, meaning that the publications met all the criteria (e.g. a monograph’s length is at least six author sheets); and (3) the filled slots were calculated by the 3N − 2N0 formula. All exceptions from these rules are clearly marked.

For the analysis, the following variables were used:

-

Five nominal variables: (1) language (all original values were re-coded to English, Polish and other languages); (2) publication type (journal article, monograph, edited volume, book chapter); (3) article journal type (A list, other); (4) field (Natural Sciences, Engineering and Technology, Medical and Health Sciences, Agricultural Sciences, Social Sciences, Humanities); and (5) patent type (national, international).

-

Four numeric variables: the number of authors from a scientific unit, the number of authors not from a scientific unit, the total number of authors, and the publication length.

-

Two rank variables: (1) year (2009–2016) and (2) journal quartile according to the 5year impact factor.

In this study, we present yearly data only on journal articles from the A list and monographs. Due to the limited number of publications and range of points, other publications types (i.e. chapter, articles from the B and C lists journals and edited volumes) were pushed out of the final set of evaluation items. On the contrary, the A list articles and monographs were assigned a substantially higher number of points; thus, there was no push out effect. This means that in the final number of publications (more precisely, evaluation items related to publications) calculated on the basis of the 3N − 2N0, there is a substantially lower number of publications in local journals or book chapters. This is why we did not analyse other publication type except the A list articles and monograph because the scale point would bias the results.

We used five-year impact factor values from a given year and rankings designed within the subject categories and not the points to avoid biases caused by changes in the range of points assigned to the A list. Based on this information, we calculated in which quartile a given journal within a subject category was classified in every year. If a journal was classified in more than one subject category, we chose the maximum value (i.e. the highest quartile). This operation allowed us to investigate whether the quality of articles affiliated with Polish scientific institutions (measured by the impact factor values) had been changing over the analysed period.

Mapping evaluation items to the OECD fields

In Poland, evaluation is conducted at the level of scientific units. In this way, all publications and patents are classified to fields according to the organisational classification (Daraio and Glänzel 2016).

Each scientific unit was assigned to one of the 60 Joint Evaluation Groups in the 2013 evaluation and 67 Joint Evaluation Groups in the 2017 evaluation. For instance, all faculties of history were assigned to a single Joint Evaluation Group for the units from higher education institutions, and institutes of the Polish Academy of Sciences from the social sciences and humanities group were assigned to their single Joint Evaluation Group.

For the purpose of the analysis, we manually assigned each of the 1000 + scientific units according to their Joint Evaluation Group and type of science to one of the six Fields of Science and Technology of the OECD fields.Footnote 1 All scientific units from the group of art sciences and artistic production were excluded from the final dataset because in the overwhelming majority they submitted artworks and not publications to the evaluation. All the publications and patents of a given scientific unit were assigned to one OECD field.

Publication types

All publications in both the 2013 and 2017 evaluations were classified into one of four publication types: journal article, monograph, edited volumes and book chapters.

Publications were translated into points a given unit could obtain (Kulczycki et al. 2017). The average of points per FTE (not only obtained via publications but also via other R&D activities) served to assign the scientific category (A+, A, B, C) for the unit, which expressed the quality of outcome and activities of a given scientific unit. Scientific categories are used as an indicator in the formula for annual distribution of government block grants to scientific units.

Journal articles were assessed according to the Polish Journal Rankings (Kulczycki and Rozkosz 2017) published in 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2015 and 2016 by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland. Each ranking consists of three lists: A, B and C. The number of points assigned to a journal depended on the following:

-

A list (15–50 points): journals with a five-year impact factor (or two-year impact factor if the five-year impact factor was not available). The number of points was normalised using the WoS subject categories.

-

B list (1–15 points): journals not indexed in the Journal Citation Reports were assessed according to various formal (e.g. the share of authors from foreign institutions) and bibliometric (e.g. the predicted impact factor) criteria.

-

C list (10–25 points): journals indexed in the European Reference Index for Humanities. The number of points depended on the journal category within the index.

During the 2009–2016 period, numerous changes to the Polish Journal Ranking regulations were implemented, especially for the B list. The most significant changes concerned the range of points assigned to journals indexed in the 2009–2012 period (a normalisation was not conducted): articles from 2009 had a substantially lower number of points in relation to articles published in the same journals after 2009. This change, in combination with the 3N − 2N0 formula, provided an unusually large number of publications in the B list from 2010 in relation to publications from 2009 and 2011–2012 in the final dataset used in the evaluation.

Monographs (20 or 25 points according to the publication language), edited volumes (4 or 5 points according to the chapter language) and book chapters (4 or 5 points according to the chapter language) were assessed according to various formal and technical criteria presented in Table 1. The 3N − 2N0 formula and a low number of points assigned to book chapters also provided in the final dataset a share of book chapters substantially lower than when we took into account all the publications that were not limited by any formula (Kulczycki et al. 2018).

Results

Characteristics of the publications included in the 3N − 2N 0 limit

Table 2 shows the distribution of publication types in the period 2009–2016. For the analysed period 452,277 publications were submitted for the two evaluation exercises. The highest number of researchers (more precisely, FTE of academic staff members) were from Engineering and Technology (22,195), and the lowest number of researchers from Agricultural Sciences (7326). In the so-called hard sciences, the highest share was constituted by journal articles from the A list (from 38.3% in Engineering and Technology to 88.4% in Natural Sciences), whereas in Social Sciences and Humanities this share was 7.1% and 2.4%, respectively. Journal articles from the B list played a major role in Social Sciences. Monographs were prevalent in Social Sciences and Humanities. However, in none of the fields was the share close to the limit (e.g. only 23.1% of monographs in Humanities, where the limit was 40%). Patents were submitted in all fields except for Humanities. The highest number of patents was submitted in Engineering and Technology (7010 patents), the lowest number of patents was submitted in Social Sciences (48 patents), and no patents were submitted in Humanities. In Table 2, we present all submitted patents except those rejected by the evaluators.

Publication patterns: articles in journals indexed in the Journal Citation Reports

Table 3 shows the distribution of journal articles published in the A list journals (indexed in the JCR) per quartile (calculated according to the procedure described in Sect. 3.1) in the period 2009–2016. The total number of publications submitted by all scientific units was 237,158, of which 84.5% (200,417 publications) was included in the final number of publications limited by the 3N − 2N0 formula. A significant growth in the number of publications classified was observed; for example, there was an increase from 4930 publications in Q1 in 2009 to 13,363 publications in Q1 in 2016. In total, the number of publications multiplied in each quartile: the number of publications in Q1 rose to 2.7 times between 2009 and 2016, to 2.6 in Q2, to 1.9 in Q3 and to 2.1 in Q4.

Because of the points scale, if a unit has a large number of publications from the A list, only publications with the highest number of assigned points fall within the 3N − 2N0 limit. The overall number of publications in the A list increased over the analyzed period, and as a consequence, some with the lowest number of points were not taken into account in the evaluation. Over the analyzed the eight-year period the number of researchers who were an author or co-author of at least one publication during a year had grown 70% from 20,261 to 34,508.

Figure 1 displays the share of publications limited by the 3N − 2N0 formula from the A list per type quartile across the OECD fields in the period 2009–2016. In all fields, the publication patterns were stable. Nonetheless, there was a small growth in the share of publications in Q1. The highest share of publications in Q1 was in Natural Sciences, and the lowest share was in Humanities.

Figure 2 shows the number of academic staff members publishing in the A list journals across the OECD fields in the period 2009–2016. There are two numbers in each field: the number of academic staff members whose publications were submitted and not rejected, and the number of academic staff members whose publications were included within the 3N − 2N0 formula limit. In total, the number of academic staff members (whose publications from the A list journals were submitted and not rejected) rose in each field. The number of academic staff members in Natural Sciences rose by 2.2 times between 2009 and 2016, by 1.9 in Engineering and Technology, by 1.8 in Medical and Health Sciences, by 2.3 in Agricultural Sciences, by 3.5 in Social Sciences and by 5.1 in Humanities. Natural Sciences had the largest number of publications not included in the 3N − 2N0 limit, meaning that there were more articles than slots for publications which could be included in the 3N − 2N0 limit.

Figure 3 displays the number of authors of A list articles. Three values for each field are presented: the mean number of authors from a scientific unit, the mean number of authors not from that scientific unit and the total number of authors. In all groups of sciences except Social Sciences, the number of external authors rose as a result of an increase in scientific cooperation. The results in Natural Sciences and Engineering and Technology were disrupted by publications from high-energy physics, in which publications with thousands of authors are quite common.

Publication patterns: monographs

Figure 4 shows the median length of monographs across the OECD fields. In the Polish system, an author sheet is used as a unit of analysis: one author sheet is 40,000 characters (approximately 6000 words). We used the median instead of the mean length because there were outliers caused by the small number of dictionaries, encyclopaedias and handbooks (especially in Medical and Health Sciences) which had a few standalone volumes, but were counted as a single publication with an excessive number of author sheets. As the length of the monograph was the key criterion of the scholarly book evaluation, and there were no other quantitative criteria, the changes in monograph length could show that science policy influences publication patterns.

In all fields the median length was stable and no substantial variances were observed, despite changes in the definition of monographs from three to six author sheets as a counted type of publication in the evaluation. In almost all years in all fields, the mean length of monographs was between 8 and 16 author sheets. Humanities had the highest median, while Medical and Health Sciences and Agricultural Sciences had the lowest median.

Figure 5 displays the share of monographs written in English. Overall, in the 2009–2016 period, 86.3% of monographs were written in Polish, 9.3% were written in English, 3.4% were written in congress languages (other than English), and 1.1% were written in other languages. The share of monographs in English was rather stable in all fields except Natural Sciences, in which there was a substantial drop in 2013.

Figure 6 presents the mean number of authors across the OECD fields. In the whole period the mean number of authors was stable.

Patents

Figure 7 shows the number of patents submitted across the OECD fields in the period 2009–2016. In this comparison we used all submitted patents that were not rejected by the evaluators (i.e. not limited by the 3N − 2N0 formula). Humanities had no patents submitted in this field. Until 2012, there was substantial growth in the number of obtained patents. From 2013 the number of obtained patents stabilised, with a small decline in Agricultural Sciences.

The share of actual publication output we see in the evaluation

Since 2013, information about all publications by Polish scholars has been gathered in a national-level database: the Polish Scholarly Bibliography (PBN). Scientific units are responsible for the quality of data submitted to the PBN. A data quality check was only performed by KEJN for publications included within the 3N − 2N0 limit. Table 4 displays the number of publications produced by Polish researchers in the period 2013–2016. We assume that, ideally, the PBN covered the total volume of publications from all fields in Poland.

From all the scientific units, 805,806 publications were submitted in the 2013-16 period, of which 565,161 (70.1%) were submitted for evaluation and 240,965 (29.9%) were included in the final number of publications limited by the 3N − 2N0 formula. A total of 161,519 of the A list articles were submitted to the PBN by all the scientific units. Moreover, 159,648 (98.8%) of the A list articles were submitted to the 2017 evaluation and 121,720 publications (75.4%) were included in the final number of publications. There were 55,257 monographs, of which 33,345 (60.4%) were submitted to the evaluation and 20,457 (37.0%) were included in the final number of publications.

Discussion

Rijcke et al. (2016) show that the indicators affect the behaviour of institutions and individual scientists. The objectives of a scientific policy must be translated into a system of consistent indicators used throughout a system. Such a translation is needed in order to ensure that institutions and scientists in their daily work should not feel that what they must report is different or even incompatible from what must be delivered. On the basis of the conducted analysis, it can be concluded that in the scope of enhancing the effectiveness of Polish science, Poland has managed to build a coherent system consisting of a research evaluation system, academic promotion procedures and grant agencies.

Our findings show that the regulations of the Polish Journal Ranking for journals with an impact factor are working well. Namely, the number of publications indexed in the JCR has been growing steadily, and there is still potential to maintain this growth for another two or three evaluation periods. It is noteworthy that although the shares of publications in the JCR according to the quartiles were stable from 2009 to 2016, the number of publications from the JCR submitted for evaluation multiplied almost three times (from 15,624 in 2009 to 42,826 in 2016). This means that Polish researchers were able to increase productivity without decreasing the quality of their publications (in terms of the JCR quartiles).

We believe that the Polish model can be improved by implementing a non-linear scale that promotes publications in journals in higher quartiles (e.g. the current 15–50-point scale could be changed to a 10–100-point scale, for example). A new scale could prepare the Polish model for greater saturation with JCR publications. At present this can be observed in Natural Sciences, in which year by year, more and more publications from Q3 and Q4 have been pushed out by the 3N − 2N0 limit.

Moreover, the growth in researchers publishing in the JCR journals may be acknowledged as a desired outcome of the Polish science policy. This means that the publication output in the JCR journals had increased not only by a small group of researchers who publish more each year, but also by other researchers who b to publish in top-tier journals. If we assume that this trend continues, then good patterns and practices could also spread to other fields that are not as research-intensive (e.g. Social Sciences).

The PBN shows that the productivity of Polish researchers is stable; in other words, a similar number of papers are published each year. Nonetheless, the 3N − 2N0 formula has produced a bigger share in the total volume constituted by publications in desired (from the science policy perspective) publication channels.

The effectiveness of Polish science is also visible in the WoS Core Collection: InCites Dataset (see Fig. 8). The Category Normalised Citation Impact before 2009 was relatively stable between 0.78 and 0.82. Later it had risen to 1.17 in 2016. This demonstrates that the A list with a scale from 15 to 50 points fulfils its role, i.e. it encourages publishing in the JCR journals. The results of Polish researchers are being progressively more cited and are becoming increasingly visible in the world.

The whole counting method for multi-authored publications used in Poland encourages collaboration with external research units, both national and foreign. This counting method allocates the full number of points regardless of the contribution from a given unit. It was very profitable to enter research collaboration with external partners, especially for units with not such a strong publication register because it was a win–win situation. All of the participating units did not lose anything from the evaluation exercise point of view.

During the 2009–2016 period, the monograph patterns were also stable. A few times the policy makers changed the minimum length of monographs (from three author sheets to six authors sheets). In the policy document there is no information regarding why such a criterion was implemented. As our results show, however, in the whole period, the mean number of sheets was at least two times higher than required in all the OECD fields. This may show that those policy decisions were not based on empirical data on what books (in terms of the number of author sheets) researchers actually published. It was rather an instrument through which ‘too short books’ could be excluded from the evaluation, where such short monographs were an easy way to play the system and to obtain more points.

In our view, changing the regulations on the monograph length may be perceived as a type of ‘enhancement strategy’ of making the evaluation system more coherent and resistant to exploitation of the system gaps. Unlike the ‘enhancement strategy’, other regulations may be perceived as instruments of ‘influencing strategy’ that serve to incentivise specific channels of scholarly communication (e.g. the highest number of points for articles in journals with an impact factor) and other areas of scholarly publishing (e.g. publication counting model that favours publishing with researchers external to a scientific unit, which may increase the level of cooperation).

Regarding the publication language, the share of monographs in English was stable for the whole period for all fields except Natural Sciences, where a significant drop occurred in 2013. This drop resulted from the implementation of the regulations for academic promotion procedures: the last chance to be evaluated according to the old criteria was September 2013. Also, the mean number of monographs was stable.

Our analysis shows that the instruments designed for changing publication patterns, on one hand, worked as intended in the area of publications in top-tier journals, and, on the other hand, changed almost nothing in terms of the publication of monographs. If the policy instruments had not changed the publication patterns (either in a good or a bad way) for eight years, this may mean that the instruments were not well designed. Monographs were assessed according to various technical criteria which do not allow for differentiating good from bad quality monographs. Thus, researchers have not followed the incentives and have not changed their publication patterns (e.g. the share of monographs in English did not increase significantly). In our opinion, in the next version of regulations for monograph evaluation, such detailed formal criteria should be abandoned and other instruments should be implemented, such as the ranking of publishers of a peer-reviewed label (Giménez Toledo 2016).

The analysis of patent patterns reveals that the science system in Poland has saturated itself. From our point of view, therefore, it will be difficult to increase the annual number of obtained patents using only policy instruments focused on research evaluation. Giving more points for patents will not encourage scientific units to produce more patents because there is no unutilised research. Thus, aiming to increase more patents should be followed by introducing new instruments, such as programmes implemented by national funding agencies.

Uncovering the relationship between science policy and publication patterns remains a difficult task and is often inconclusive. We are aware that during the analysed decade there were factors other than those indicated in the three areas (i.e. research evaluation, academic promotion procedures and competitive grants) that could have influenced publication patterns. For instance, the growth in the number of journals indexed in the JCR from Central and Eastern European countries with which Poland researcher have a close cooperation or a generational change, manifests itself in the higher share of researchers who had rather English than Russian as a foreign language in school. Moreover, other factors related to mobility, like amendments of air transport availability (Ploszaj et al., 2018) could also influence cooperation and eventually the number of co-authored publications reported by Polish scientific institutions. Nonetheless, it is difficult to build statistical models when there are so many interdependent factors. Similar observations are raised by Aagaard and Schneider (2017), who ask the question of what we can learn from studies on the relation between science policy and perfomance. According to the authors, cases such as the one presented in this paper can improve our general understading of how the mechanisms actually work in a complex scientific system. We share the view that the lessons derived from the various national cases are not directly transferrable from one country to another. It also means that a study from one country should not justify policy decisions in another country. There are always very specific contexts that must be considered in the desigin and implementation of policies.

Conclusion

In this paper we reconstructed the goals of Polish science policy regarding publication patterns from 2007. The diversity of new instruments introduced by the reforms implemented from 2009–2012 show that the Polish government payed attention to how researchers communicate their research and what channels of publications they chose.

Focusing on increasing the effectiveness of science—understood as the share and number of publications indexed in the international databases—worked well. Thus, policy instruments related to this goal should be used for a longer period because Polish researchers still have the capacity to publish more and better publications. Understandably, improving the current system by changing the point scale for A list journal publications can encourage researchers to improve their publication practices.

We argue that micro-management within the evaluation regulations is unnecessary. The over-regulated criteria for monographs did not influence publication patterns. Moreover, the micro-management in this area (e.g. indicating the minimum number of author sheets) was not properly expressed by clear scientific policy expectations.

Overall, the Polish experience from 2009 to 2016 shows that science policy can shape publication patterns in a targeted way but only when the instruments are well fitted, science policy expectations are explicitly stated, and instruments are used coherently throughout the evaluation system, academic promotions regulations, and grant agencies. Such a science policy can improve publication patterns. However, policy makers need to remember that the effects of the policy are not immediately visible. Sometimes, it takes a decade to see how researchers have actually adapted to new circumstances and how the policy has influenced their publication practices.

Notes

OECD: revised field of science and technology (FOS) classification in the Frascati manual, version 26-Feb-2007, DSTI/EAS/STP/NESTI (2006)19/Final.

References

Aagaard, K. (2015). How incentives trickle down: Local use of a national bibliometric indicator system. Science and Public Policy, 42, 725–737. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scu087.

Aagaard, K., & Schneider, J. W. (2017). Some considerations about causes and effects in studies of performance-based research funding systems. Journal of Informetrics, 11, 923–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.05.018.

Aksnes, D. W., Schneider, J. W., & Gunnarsson, M. (2012). Ranking national research systems by citation indicators: A comparative analysis using whole and fractionalised counting methods. Journal of Informetrics, 6, 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2011.08.002.

Antonowicz, D., Kohoutek, J., Pinheiro, R., & Hladchenko, M. (2017). The roads of ‘excellence’ in Central and Eastern Europe. European Educational Research Journal, 16, 547–567. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116683186.

Bal, R. (2017). Playing the indicator game: Reflections on strategies to position an STS group in a multi-disciplinary environment. Engaging Science, Technology, and Society, 3, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.17351/ests2017.111.

Balazs, K., Faulkner, W., & Schimank, U. (1995). Transformation of the research systems of post-communist Central and Eastern Europe: An introduction. Social Studies of Science, 25, 613–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631295025004002.

Beck, M. T., & Gáspár, V. (1991). Scientometric evaluation of the scientific performance at the Faculty of Natural Sciences, Kossuth Lajos University, Debrecen, Hungary. Scientometrics, 20, 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02018142.

Butler, L. (2003). Explaining Australia’s increased share of ISI publications—the effects of a funding formula based on publication counts. Research Policy, 32, 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-7333(02)00007-0.

Butler, L. (2005). What happens when funding is linked to publication counts? In H. F. Moed, W. Glänzel, & U. Schmoch (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative science and technology research: The Use of publication and patent statistics in studies of S&T systems (pp. 389–405). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Butler, L. (2017). Response to van den Besselaar et al.: What happens when the Australian context is misunderstood. Journal of Informetrics, 11, 919–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.05.017.

Daraio, C., & Glänzel, W. (2016). Grand challenges in data integration—state of the art and future perspectives: An introduction. Scientometrics, 108, 391–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1914-5.

Engels, T. C. E., Ossenblok, T. L. B., & Spruyt, E. H. J. (2012). Changing publication patterns in the social sciences and humanities, 2000–2009. Scientometrics, 93, 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0680-2.

Eurostat (2018). Total R&D personnel by sectors of performance, occupation and sex [WWW Document]. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=rd_p_persocc&lang=en. Accessed August 5, 2018.

Franzoni, C., Scellato, G., & Stephan, P. (2011). Changing incentives to publish. Science, 333, 702–703. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1197286.

Giménez Toledo, E. (2016). Assessment of journal & book publishers in the humanities and social sciences in Spain. In M. Ochsner, S. E. Hug, & D. Hans-Dieter (Eds.), Research Assessment in the Humanities: Towards Criteria and Procedures (pp. 91–102). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29016-4_8.

Główny Urząd Statystyczny (2017). Szkoły wyższe i ich finanse w 2016 r. Higher Education Institutions and their Finances in 2016. Warszawa.

Hammarfelt, B., & de Rijcke, S. (2015). Accountability in context: Effects of research evaluation systems on publication practices, disciplinary norms, and individual working routines in the faculty of Arts at Uppsala University. Research Evaluation, 24, 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvu029.

Heinecke, S. (2016). The gradual transformation of the Polish public science system. PLoS ONE, 11, e0153260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153260.

Heinecke, S. (2017). On the route towards renewal? The Polish Academy of Sciences in post-socialist context. Science and Public Policy, 1, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scx063.

Henriksen, D., & Schneider, J. W. (2014). Is the publication behavior of Danish researchers affected by the national Danish publication indicator? A preliminary analysis. In Noyons, E. (Ed.) Proceedings of the science and technology indicators conference 2014 Leiden ‘Context counts: Pathways to master big and little data’ (pp. 273–275). Leiden: Universiteit Leiden.

Hicks, D. (2012). Performance-based university research funding systems. Research Policy, 41, 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.09.007.

Jablecka, J. (1995). Changes in the management and finance of the research system in Poland: A survey of the opinions of grant applicants. Social Studies of Science, 25, 727–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631295025004007.

Jiménez-Contreras, E., de Moya-Anegón, F., & Delgado López-Cózar, E. (2003). The evolution of research activity in Spain: The impact of the National Commission for the Evaluation of Research Activity (CNEAI). Research Policy, 32, 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00008-2.

Knorr Cetina, K. (1999). Epistemic cultures: How the sciences make knowledge. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kozak, M., Bornmann, L., & Leydesdorff, L. (2014). How have the Eastern European countries of the former Warsaw Pact developed since 1990? A bibliometric study. Scientometrics, 102, 1101–1117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1439-8.

Kulczycki, E. (2017). Assessing publications through a bibliometric indicator: The case of comprehensive evaluation of scientific units in Poland. Research Evaluation, 26, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvw023.

Kulczycki, E., Engels, T. C. E., Pölönen, J., Bruun, K., Dušková, M., Guns, R., et al. (2018). Publication patterns in the social sciences and humanities: Evidence from eight European countries. Scientometrics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2711-0.

Kulczycki, E., Korzeń, M., & Korytkowski, P. (2017). Toward an excellence-based research funding system: Evidence from Poland. Journal of Informetrics, 11, 282–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.01.001.

Kulczycki, E., & Rozkosz, E. A. (2017). Does an expert-based evaluation allow us to go beyond the Impact Factor? Experiences from building a ranking of national journals in Poland. Scientometrics, 111, 417–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2261-x.

Kwiek, M. (2014). Structural changes in the Polish higher education system (1990–2010): A synthetic view. European Journal of Higher Education, 4, 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2014.905965.

Kwiek, M., & Szadkowski, K. (2018). Higher education systems and institutions, Poland. In Encyclopedia of international higher education systems and institutions (pp. 1–10). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9553-1_392-1

Levitt, J. M., & Thelwall, M. (2016). Long term productivity and collaboration in information science. Scientometrics, 108, 1103–1117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2061-8.

Ministerstwo Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego (2008a). Budujemy na wiedzy: reforma nauki dla rozwoju Polski.

Ministerstwo Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego (2008b). Strategia rozwoju nauki w Polsce do 2015 roku. Warszawa.

Neff, M. W. (2017). Publication incentives undermine the utility of science: Ecological research in Mexico. Science and Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scx054.

Neff, M. W. (2018). Williams and Morrone misunderstand and inadvertently support my argument: Mexico’ s SNI systematically steers ecological research. Science and Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scy031.

Pajić, D. (2015). Globalization of the social sciences in Eastern Europe: Genuine breakthrough or a slippery slope of the research evaluation practice? Scientometrics, 102, 2131–2150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1510-5.

Pan, R. K., & Fortunato, S. (2014). Author impact factor: Tracking the dynamics of individual scientific impact. Scientific Reports, 4, 4880. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04880.

Ploszaj, A., Yan, X., & Börner, K. (2018). The impact of air transport availability on research collaboration : A case study of four universities (pp. 1–23). arXiv:1811.02106.

Quan, W., Chen, B., & Shu, F. (2017). Publish or impoverish: An investigation of the monetary reward system of science in China (1999–2016). https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-01-2017-0014

Rijcke, S. de, Wouters, P. F., Rushforth, A. D., Franssen, T. P., & Hammarfelt, B. (2016). Evaluation practices and effects of indicator use: A literature review. Research Evaluation, 25(2), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv038.

Schneider, J. W., Aagaard, K., & Bloch, C. W. (2016). What happens when national research funding is linked to differentiated publication counts?: A comparison of the Australian and Norwegian publication-based funding models. Research Evaluation, 25, 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv036.

Sivertsen, G. (2016). Publication-based funding: The Norwegian model. In M. Ochsner, S. E. Hug, & D. Hans-Dieter (Eds.), Research assessment in the humanities: Towards criteria and procedures (pp. 79–90). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29016-4_7.

van den Besselaar, P., Heyman, U., & Sandström, U. (2017). Perverse effects of output-based research funding? Butler’s Australian case revisited. Journal of Informetrics, 11, 905–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.05.016.

Williams, T., & Morrone, J. J. (2018). Science is strengthened by Mexico’s researcher evaluation system: Factual errors and misleading claims by Neff. Science and Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scy004.

Wouters, P. (1999). The citation culture. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

Woźnicki, J. (Ed.). (2013). Financing and deregulation in higher education. Warsaw: Institute of Knowledge Society. Polish Rectors Foundation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Science and Higher Education for its support in making the data available for our analyses.

Funding

This work was supported by the DIALOG Programme [Grant name ‘Research into Excellence Patterns in Science and Art’].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Korytkowski, P., Kulczycki, E. Examining how country-level science policy shapes publication patterns: the case of Poland. Scientometrics 119, 1519–1543 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03092-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03092-1