Abstract

COVID-19 challenges the value systems of family firms and urges them to adapt their behaviors, affecting their identities. This study aims to explore how and why family businesses strategically respond to challenges to their identity during COVID-19. Based on a qualitative case study of six German family firms, we propose a process model of family business identity variations during COVID-19 with three propositions, highlighting the interplay between strategy and identity. Counterintuitively, we found that an exogenous shock like COVID-19 can have a positive effect on family business identity, leading to identity clarification or consolidation. We contribute to the growing stream of research investigating the impact of COVID-19 on SMEs, as well as research on family business identity heterogeneity and organizational identity literature by illustrating the interplay between strategy and identity.

Plain English Summary

The silver lining of COVID-19 for family business identity: COVID-19, as one recent exogenous shock, posed a strong challenge for family businesses. However, little is known about how family businesses deal with exogenous shocks that force strategic responses and thus challenge family businesses to question “who are we as an organization”. In this study, we investigated how strategic responses induced by COVID-19 affected the identity of German family firms. Counterintuitively, our study reveals that COVID-19 provided an opportunity for family business identity consolidation. It highlights how a firm’s unique identity stemming from the closeness with the family can serve as a guidance for strategy-making during COVID-19. Specifically, the study unearths that, when facing the uncertainty of external challenges like COVID-19, the competing family business goal systems are challenged, providing an opportunity for family business owners to refine and re-define the identity of the family businesses. Overall, it thus shows that exogenous shocks can have a positive impact on the family businesses’ identity, by leading to a consolidation of an already existing identity, as well as to a clarification of a previously unclear identity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

COVID-19, a recent exogenous shock, was unforeseeable with unpredictable duration and impact. It forced businesses to respond strategically to changing market conditions and uncertainty (Batjargal et al., 2023). As exogenous shocks, such as COVID-19, force businesses to reconsider their strategic positioning, they provide a valuable context for the study of organizational identity change (Doern et al., 2019). Exogenous shocks compel companies to not only re-evaluate their environment (look out), but above all to re-evaluate their own identity and what they want to stand for in view of the changing external conditions (look in). While the literature has pointed out that exogenous shocks have drastic and detrimental effects on small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) globally (e.g., Belitski et al., 2022; Pedauga et al., 2022; Miklian & Hoelscher, 2022), some research also found that exogenous shocks benefit SMEs by re-allocating resources to efficient SMEs (Dörr et al., 2022) and strengthen the SMEs in preparation for future shocks (Grözinger et al., 2022). However, there is still a lack of research on SMEs’ behaviors during exogenous shocks (Belitski et al., 2022).

Family firms, as the majority of SMEs in most countries, are also under a major threat (De Massis et al., 2020). To survive, family firms needed to be strategic and radically adapt to the challenges brought by exogenous shocks, like supply and demand disruption, restricted access to finance, and constraints on social interactions (Adian et al., 2020; Eggers, 2020).

However, changes in family businesses are complicated not only due to resource constraints but also due to their focus on non-economic goals (e.g., Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). As a result, family business identity can be severely challenged by COVID-19 (De Massis et al., 2020). Family businesses have to make important strategic decisions regarding their identity, defined as “who we are as an organization” (Albert & Whetten, 1985, p. 80), during the COVID-19 pandemic (Soluk et al., 2021; Le Breton-Miller and Miller, 2022). While studies highlight how identities are constructed in family firms and how they change over generations (Berrone et al., 2012; Bettinelli et al., 2022; Zellweger et al., 2013), it remains unclear how exogenous shocks impact the family businesses’ identities (De Massis and Rondi, 2020). We address this research gap by asking, “how and why do family businesses strategically respond to challenges to their identity during COVID-19?”.

Empirical research indicates that in family firms, the family identity and business identity overlap (Shepherd and Haynie, 2009). Variations in family identity result in prioritizing either financial or socio-emotional goals, and consequently, their reaction to exogenous shocks and potential organizational decline (Ponomareva et al., 2019). Reay (2009) proposes that a strong, resilient, and malleable family business identity is critical to long-term success. Shedding light on how the malleability/enduringness balance is achieved allows an understanding of why some family businesses remain competitive when facing institutional pressure, and others do not. The aim of this study is to shed light on the influence of exogenous shocks and the resulting strategic repositioning on the organizational identity of family businesses. In doing so, the objective is to highlight the possible organizational identities that family businesses may adopt and to explore the extent to which these identities may change in response to exogenous shocks and associated shifts in strategic focus.

Empirically, we investigate six German mid-sized family businesses operating in diverse industries through interviews and archives. Studying the influence of COVID-19 on German SMEs is particularly insightful because these companies, more than 90% of which are family-owned, are considered to be the engine of Germany’s economy (Stiftung Familienunternehmen, 2022). These so-called “Mittelstand” firms are resource-constrained small- or medium-sized businesses in Germany, Austria, or Switzerland (De Massis et al., 2018; Soluk and Kammerlander, 2021). Due to their unique combination of firm size (less than 500 employees) and owner–management allowing quick reactions to changing market conditions, Mittelstand firms are regarded as particularly resistant to crisis (Berlemann et al., 2021; Pahnke et al., 2023). Because of Mittelstand firms’ positioning as the “backbone of the German economy”, paired with their crisis resistance, they represent a unique phenomenon to study crisis management (Audretsch and Lehmann, 2016, Berlemann et al., 2021, p.1182). Additionally, as the German government gave a similar package to support SMEs during COVID-19, compared to other EU countries, some level of generalizability of the experiences is guaranteed when the boundary conditions of our research are met.

Counterintuitively, our analysis reveals that COVID-19 provides an opportunity for family business identity consolidation. Namely, despite research on risks and uncertainties brought about by COVID-19, our research points to a positive effect on family businesses. We find that during the pandemic, family businesses with a clear identity strengthen their identity by maintaining the strategy they executed before the shock. For family businesses with an unclear identity before the shock, the crisis simultaneously triggered stabilization and destabilization processes that facilitated clarifying the previously unclear identity. We identify three strategy changes of family firms during exogenous shocks: identity retention (focused on family and growth), identity reconstruction (focused on family), and new identity formation (focused on survival). Thus, this study reveals that COVID-19 is a strategic opportunity for family businesses to reflect on their identity of “what do we stand for” and to consider “what do we want to stand for in the future”.

Our study responds to recent calls for research on how major crises influence organizational identity (Ashforth, 2020; De Massis and Rondi, 2020) and deepens the understanding of the effect of COVID-19 on SMEs (Belitski et al. 2022). We make three main contributions. First, we contribute to family business literature, by explaining the strategic response, including the formation, alteration, and elimination, of family business identity. Our approach of combining strategic responses with family business identity extends the literature on family business heterogeneity (Daspit et al., 2021; Neubaum et al., 2019; Ponomareva et al., 2019) by showing why some family businesses see themselves more as such and others embody the family aspect less. The dynamics are further explained by our propositions clarifying the interplay between different types of identities with varying stability degrees, and a family or growth focus in their identity changes.

Second, our model responds to the call for further investigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SMEs (Belitski et al., 2022; Conz et al., 2023; Hadjielias et al., 2022; McCann et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2023) by introducing a process model of identity reconstruction during COVID-19, as an example of exogenous shock. In particular, we extend the literature on Mittelstand crisis resistance (e.g., Audretsch and Lehmann, 2016; Berlemann et al., 2021) by highlighting how Mittelstand the firms’ unique identity stemming from the closeness with the family can serve as a guidance for strategy-making during COVID-19.

Lastly, we bring in the discussion on family dynamics’ influence on organizational identity (Albert and Whetten, 1985) by illustrating the interplay between strategy and family firm identity (He and Balmer, 2007, 2013). We contribute to the understanding of organizational identity research of family businesses (Whetten et al., 2014) by shedding light on how family business identities can influence particular strategic decisions, especially on strategic change and continuity (Ravasi et al., 2020).

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Organizational identity

Organizational identity refers to “the central and enduring attributes of an organization that distinguishes it from other organizations” (Albert & Whetten, 1985, p. 80), thus not only clarifying “who we are as an organization” (Albert & Whetten, 1985, p. 80) but also “what we do as a collective” (Nag et al., 2007, p. 842; Pratt and Kraatz, 2009; Pratt et al., 2016). A clear organizational identity is a coherent guide for how members are expected to behave and how other organizations relate to them (Dutton and Dukerich, 1991; Whetten and Mackey, 2002).

2.2 Organizational strategy and identity dynamics

Scholars agree that a firm’s organizational identity is “dynamic, not static, and is greatly affected by changes in the external environment” (Balmer and Greyser, 1995; Jeyavelu, 2009; Pérez and del Bosque, 2014). Therefore, organizational identity should be adaptable and malleable to respond to changes in the external environment, the corporate strategy, and organizational members’ conflicting identity claims (He and Balmer, 2013). To deal with these challenges, scholars propose that organizational identity needs to be understood and maintained with corresponding strategies (Anthony and Tripsas, 2016; Cornelissen et al., 2007; Graddy-Reed, 2021; Rindova et al., 2011). The firm’s organizational identity determines its corporate strategy, including how it positions itself in the market, its allocation of resources, and its corporate structure (Block and Wagner, 2014; Melewar and Wooldridge, 2001; Ravasi et al., 2020). Strategic tensions, discrepancies between the values that constitute the identity, goals, and strategy implementation, entail continuously reinterpreting, experimenting, nudging, and reinterpreting the identity (Kreiner et al., 2015). As a result, a certain level of organizational identity flexibility is needed over time to enable the firm to shift strategically (Smith and Besharov, 2019).

However, due to the involvement of various stakeholders in forming the organizational identity, identity inconsistency or conflicts may ensue (Gioia et al., 2010; Rodrigues and Child, 2008), meaning multiple organizational identities compete for predominance (Daft and Macintosh, 1981).

In the following, we refer to identity inconsistency as a temporary state of misalignment of strategy and identity resulting from a shifting identity and/or strategy, leading to a lack of a collective understanding of the organizational identity (Bövers and Hoon, 2021). Inconsistency results from misalignment of strategy and identity, caused by (1) changes in strategy (identity inconsistency), (2) changes in identity (strategy inconsistency), (3) or both (strategy–identity inconsistency) (Bövers and Hoon, 2021). Organizational identity serves as a filter that can direct the organization’s attention, but can also blind it to market opportunities or other changes that would require a change in corporate identity (Ravasi et al., 2020).

Drastic identity instability occurs during key moments of institutional transformation, such as organizational restructuring, leadership changes (Balmer and Greyser, 2002), spin-offs, forming strategic alliances, mergers and acquisitions (van Knippenberg et al., 2002), potentially causing changes to the organizational identity and requiring a re-alignment between the strategy and identity (Ravasi et al., 2020). Drastic identity instability occurs during key moments of institutional transformation, such as organizational restructuring, leadership changes (Balmer and Greyser, 2002), spin-offs, forming strategic alliances, mergers, and acquisitions (van Knippenberg et al., 2002), potentially causing changes to the organizational identity and requiring a re-alignment between the strategy and identity (Ravasi et al., 2020).

2.3 Family business identity

In family firms, the development of an organizational identity entails complex dynamics ensuing from the interplay between the family and the business (Harrison and Leitch, 2019), in turn determining family firm behaviors (Habbershon et al., 2003; Zellweger et al., 2010). Family firms’ vision is shaped and pursued by a dominant coalition that constitutes the family or a small number of families (Chua et al. 1999). Bettinelli et al. (2022) further emphasize that the identity of family firms is shaped by complex interactions between actors at different levels inside and outside the firm, both from family and non-family members. The construction of an organizational identity lies in the hands of firm leaders (Balmer, 2008; Kärreman and Rylander, 2008), or the family coalition in family firms (Chrisman et al., 2003). Recently, Bövers and Hoon (2021) have highlighted the interplay of strategy and identity by showing that when navigating through times of change family firms’ identity is inextricably linked to strategy, causing identity adaptation, modification, and change. In family firms, the business and family identities may be segmented or integrated to different degrees. In the case of segmentation, the firm has its own identity autonomous from the family (Sundaramurthy and Kreiner, 2008). Family identity is defined as “the set of behavioral expectations associated with the family role” (Shepherd and Haynie, 2009, p. 1251) or the meaning that family members attach to the family for internal self-verification (Weigert and Hastings, 1977; Zellweger and Dehlen, 2012).

When the family and business identities overlap and intersect, a “meta-identity” arises (Shepherd and Haynie, 2009, p. 1246). The co-existence of both a family and a business identity implies that the rationale for decisions (e.g., on management, finance, and strategy) and behaviors could be based on either of the two identities (Boers and Nordqvist, 2012), termed as paradoxical goal systems (Barrett and Moores, 2020). These competing goals invite research on the trade-offs between family and business logic (McAdam et al. 2020)

For family firms, understanding “who we are as a family business” is especially important, as the firm is often much more than just a business, a manifestation of the individual and collective identity, and a source of recognition and pride (Parada and Viladás, 2010; Berrone et al. 2010). Due to their emotional attachment to the firm, the family acts as a “keeper of the past,” or “guarantor of care and continuity” (Micelotta and Raynard, 2011, p. 204). The business, on the other hand, reflects “temporality as a disconnection from the past and a projection into the future”, as it focuses primarily on financial development (Micelotta and Raynard, 2011, p. 209).

Research is aligned on the heterogeneity of family business identities and behavioral differences (Daspit et al., 2021; Neubaum et al., 2019; Rau et al., 2019). Ponomareva et al. (2019) propose that family firms’ strategic behaviors are influenced by two opposing identities—the clan identity, meaning the family is the carrier of the identity and the central decision-making factor, and financial identity, where business values take priority. A growing stream of research addresses the influence that organizational identity has on family firms’ strategic decision-making such as family firms’ repose to technological transformation (Prügl and Spitzley, 2021), the utilization of mottos and philosophies during change (Sasaki, et al., 2020), or the role identity plays in family firms conducting (un)ethical behavior (Dieleman and Koning, 2020).

Despite the array of studies focusing on organizational identity deviation, there is a lack of research on how changes in the external environment, such as COVID-19 influence the family business identity (Bövers and Hoon, 2021; De Massis and Rondi, 2020). Remaining unclear are the dynamics between identity and strategy during shocks, what value the organizational identity can provide in crises, and the role that family and non-family members play in maintaining and shaping the identity in times of institutional pressure. Therefore, our research follows the call to investigate how different types of identities affect strategic decisions and the impact of diversely constructed identities on strategic change and continuity in the context of family firms (Bettinelli et al., 2022; Ravasi et al., 2020).

To determine how and why COVID-19 affects family business identity, we consider the rich family business narratives (Dawson and Hjorth, 2012, p. 350). In the next section, we elaborate on our research methodology.

3 Methodology

Due to the explorative nature of our study (De Massis and Kammerlander, 2020), we answer our research question through inductive theory-building based on qualitative data (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). Because there is limited prior research, we use a broad research question of “how” and “why” that allows us to flexibly address observed phenomena (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). The aim of our inductive approach is to explain variance in strategy and identity processes and the resulting outcomes, understanding the underlying motives (Eisenhardt et al., 2016). Through our inductive exploratory research, we gain in-depth insights into changes of the organizational identity of family businesses, including the underlying values of family members, the relationship between non-family and family members, and the firms’ self-reflexivity processes, all complex social progressions not easily captured by quantitative data (Cassell et al., 2017).

We follow the recommendations by De Massis and Kotlar (2014) to use multiple data sources and multiple rounds of validation to triangulate our findings, i.e., apply different angles to observe the same phenomenon to inductively develop our theoretical propositions, ensuring construct validity (Yin, 2009). In doing so, we seek to rule out misleading interpretations of data from the initial research questions to the model and propositions. The propositions aim to inspire future confirmatory research thus strengthening the “testability” of our findings (De Massis and Kotlar, 2014). To achieve a high degree of reliability, after the two rounds of interviews and secondary data collection had been completed, the findings were shown to the CEOs of the six family businesses (De Massis and Kotlar, 2014).

3.1 Data collection

We followed a “theoretical sampling” approach (Symon and Cassell, 2017, p. 42) whereby we collected, immediately analyzed, and coded the data to generate a first theory that then allowed for improving and specifying the questions we asked in the subsequent interviews.

For adequate comparability, we carefully selected the six German “Mittelstand” SMEs (Pahnke et al., 2023; Pahnke and Welter, 2019), all of which conform to the European Commission definition of family firms (European Commission, 2021a), and small- and medium-sized enterprises (European Commission, 2021b). Studying strategic responses to shocks in Mittelstand firms is especially insightful as Mittelstand firms are not only regarded as constructive pillars of the German economy, but also because of their especially high crisis resistance due to their size, concentrated ownership structure, and closeness to their customers (Berlemann et al., 2021; Franch Parella and Carmona Hernández, 2018).

As suggested in the literature (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2009), we settled on a theoretical sample of six German family firms of similar size, revenue, and age, but differing in terms of industry and response to the exogenous shock. SMEs were chosen due to their size and the resulting limited resources and ability to influence their external environment, SMEs are more severely impacted by exogenous shocks than larger firms (Miklian & Hoelscher, 2022). Studying the impact of COVID-19 on German family businesses is particularly insightful for two reasons. First, in Germany, more than 90% of all companies are family-owned and contribute 58% of all jobs, thus a stabilizing factor of the employment market in times of economic downturn (Stiftung Familienunternehmen, 2022). Second, by specifically supporting SMEs, Germany has issued the most comprehensive financial aid measures in the history of the country (Federal Ministry of Finance, 2022). Before the pandemic, the selected family SMEs employed between 15 and 50 people and generated between €4 m and €10 m in revenues. The majority of decision-making rights are in the hands of the family, and at least one family representative or kin is formally involved in the firm’s governance.

For a holistic view of the influence of COVID-19, we selected firms operating in various industries that faced different obstacles during the pandemic. Thus, the cases build a “common process design”, as all observed the same phenomenon, namely COVID-19, but in different settings (Eisenhardt, 2021, p. 150). Although the companies operate in different industries, they have in common that they were all initially negatively affected by the pandemic and had to shut down their operations for more than 10 days. All six companies did not apply for financial assistance from the government but initially suffered financial losses in the second quarter of 2020. Using this design, our research facilitates generalizations and higher external validity. Theoretical replication and the observation of similarities in cases with different theoretical conditions allowed a more robust understanding of the relationship between COVID-19 and family business identity, strengthening the internal validity of our multiple case study (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). To anonymize the firms and the associated families, we have allocated them Greek letters (see Table 1). All six family businesses were wholly owned and managed by the family at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. A total of 60% of the company Gamma was sold to another family business 11 months after the onset of the pandemic. Gamma family retains 100% ownership for the remaining 40% of Gamma and continues to be responsible for the management of this part of the company, where we based our analysis on.

We collected our data from three sources to ensure a thorough understanding of the cases and allow data triangulation (Yin, 2009), namely the firms’ digital archives including press websites, internal communication and external communication, documentation (annual reports and corporate documents), and qualitative interviews. The interviews were conducted between May and August 2021 in two rounds. We further conducted a round of validation interviews in January 2023.

Data was collected in two rounds. In round one, openly available information, such as press websites, corporate reports, and newspaper articles was evaluated. After analysis of the secondary data, 13 interviews with family CEOs, CIOs, retired former CEOs, NextGen, or heads of sales were conducted as well as two interviews with non-family managing directors. Also, internal communication (archival items sent to employees, customers, and partners) was gathered to understand how the market responded to the exogenous shock and how the crisis is described. Through analysis of external sources (websites of competitors, trade unions, and associations), the interviewees’ statements were validated or refuted to be questioned again in the second round of interviews. In round two, which took place 3 weeks after the first interviews, a further eight interviews were conducted with family CEOs, in which unclear or contradictory statements from the previous interviews were questioned. As recommended by Eisenhardt (2021), to select the relevant data, rather than aiming to increase the quantity of data, we decided to focus on family members in the second interview round, as non-family managers, despite having opinions on the strategy and identity of the business, do not have the power to influence these strategies. We were satisfied with the data collection after eight interviews in the second interview round, as no new information was gathered thereby reaching data saturation (Fusch and Ness, 2015). To achieve further validation of the collected data, the information collected was presented to the owning family via email and validated by them.

During data collection, we followed Eisenhardt’s (1989) suggestion on using probing questions, such as “Prior interviews have shown…”, “Why/why not?” or “What would have happened if…?” (De Massis and Kammerlander, 2020, p. 11), to achieve validation. To collect the most diverse information possible, minimize biases, and achieve a high degree of triangulation, the interviews were conducted with the generation currently running the firm and at least one family or non-family senior executive. A total of 23 interviews were conducted in which the information was triangulated by within-case comparison. Data collection was discontinued after 23 interviews and the use of secondary data, as data saturation had been reached and statements by individual informants and between informants were duplicated and no new information could be obtained (Fusch and Ness, 2015).

We further conducted a validation round with all six family businesses. During this stage, we discussed our findings and the process model with the family business CEOs and interviewed all six CEOs of family businesses to learn how the identity of the businesses had changed since the shock due to the strategic responses triggered by the shock. By showing our results to the CEOs, we have been able to triangulate our findings, increasing the level of detail of our data structure and confirming the validity of our model (De Massis and Kotlar, 2014; Yin, 2009).

First, we formed the questions drawing on the existing literature, then iteratively refined and expanded them from interview to interview (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). As we encouraged the interviewees to tell stories and provide vivid examples, an increasingly detailed picture of their understanding of the business identity emerged (Eisenhardt, 1989). Thus, our theoretical results are grounded in our data (Table 2) yet developed and refined through constant comparison with the existing literature (Eisenhardt, 2021).

During the first interviews, we only looked at changes in identity but quickly realized that the changes were significantly influenced by the chosen strategy. Throughout the interviews, it became increasingly clear to us that identity and strategy are mutually interdependent. We therefore iteratively expanded our research to shed light on the interplay of strategy and identity. In total, we collected 1192 min of interviews, generating 506 pages of transcripts. The length of the interviews is attributable to the different lengths of interviewees’ answers as well as the adaptation of the interview guide depending on the interviewees’ responses.

3.2 Data analysis

We conducted an inductive thematic analysis of our data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Employing a constant comparative method, in the first cycle, we used an open coding mechanism to form concepts from the data, subsequently developing the most frequent into more defined themes (De Massis and Kammerlander, 2020). The interviews were conducted in such a way that once a deep understanding of what each company stood for before the pandemic was achieved; rough categories were first formed from the raw data to address how the individual interviewees perceived their company before the shock. In doing so, we drew within-case and cross-case insights and classified the family businesses into two categories: family firms with a stable identity and family firms with an unstable identity. This process allows us to not only explain “what differs” but also the depth of how these differences appeared in different cases, and the distinctiveness of family influences on businesses’ strategic behaviors (Chrisman et al., 2016). Also, two logics emerged from these first interviews, family logic and growth logic.

The second round of interviews evaluated how the companies described themselves during the pandemic and what strategic steps they took during the shock. Also, the codes from the first round were refined and adapted in the second round. By repeatedly reshaping, combining, or deleting codes, the rough first-or concepts resulted in increasingly clear second-order codes that enabled a higher level of theoretical abstraction. For example, after realizing that the identity of family businesses was affected by the strategic reorientations necessitated by the pandemic, we expanded our code system to reflect this. Specifically, the second-order themes’ lack of strategic direction, threats to business survival, and need to change and adapt resulted from validating the findings from the first round of interviews with CEOs with additional family and non-family members. Through constant refinement of the second-order themes within and across cases as well as the timing of the events, the overarching dimensions then emerged (Gioia et al., 2013).

All authors compared and reviewed the codes independently to increase rigor. All authors, based on initial coding by one author, looked at the codes and discussed how they could be abstracted into higher second-order themes and consequent overarching dimensions. Thus, different interpretations of the quotes were discussed and interview questions for the next round of interviews were developed. As our theory emerged, we repeatedly verified and confirmed insights through focused questioning. Our iterative verification and discussions eventually led to our final process model.

To reveal the individuals’ perceptions of “who we are as a family”, “who we are as a business”, “who we are as a family business”, and “what the shock means to us”, we conducted a thematic analysis of family members’ narratives. In family businesses, sharing narratives about the family contributes to the creation of a shared identity and reduces the disparity between the family identity and the firm identity (Dalpiaz et al., 2014; Jaskiewicz et al., 2015). Sharing narratives about the family imbues a sense of where the family comes from, how they got to where they are, and why they do the things they do (Parada and Viladás, 2010). The often informally communicated stories, legends, and myths nourish and clarify why some strategies emerged (Discua Cruz et al., 2012) and even form part of these strategies (Ge et al., 2022). Therefore, we specifically analyzed the personal accounts of the interviewees’ experiences (De Fina and Georgakopoulou, 2015; Larty and Hamilton, 2011), focusing on the narratives of events, the relational and historical context, and the relationship among the stories (Smith, 2018; Somers, 1994). These narratives include “personal and social histories, myths, fairy tales, novels or everyday stories that are used to explain or justify our own, or others, actions, and behaviors” (Smith and Anderson, 2004, p. 127).

After the within-case interpretations, to achieve internal validity, we moved on to make cross-case interpretations focusing on differences and similarities in the patterns from each of the studied cases (De Massis and Kotlar, 2014). Following the initial cross-case interpretations by comparing the empirical patterns identified in the within-case interpretations, we identified more general themes from the patterns that emerged during the interpretive work (Nordqvist et al., 2009).

Guided by our aim to understand the effects of COVID-19, we identified the three stages by asking the interviewees retrospective as well as prospective questions regarding their strategies and identities regarding the beginning of the pandemic, current descriptions, and future plansFootnote 1. In particular, “first encounter” refers to the period when the family business identity first faced the challenge, was under threat, and needed change. The “new normal” refers to the outcome of the identity-stabilizing strategy in the previous period. These accounts were triangulated with archives for validation. For example, we check the self-identifying of the interviewees with the websites and the company documentation. Since the description of the family businesses on their websitesFootnote 2 was very vague and did not go beyond the description of “family business”, we based our analysis on our primary research data (interviews) and other archive data. The family businesses have not made any statement regarding their strategies on their websites, which can be attributed to the fact that the websites are not perceived to have a high value for their external marketing. We witnessed strategic changes in all six firms with interesting directions. Further, we formed comparisons between cases. For example, we grouped the case changes based on the themes that emerged from data—family- or growth-focused logic. These formed the initial propositions, which we discuss further in the discussion section. We grouped the identity-related narratives into three different stages—before COVID-19, first encounter, and new normal—and coded their different themes accordingly. Our data analysis consisted of two phases. Triangulation was achieved by asking different interviewees in the same company the same question as well as analyzing secondary data to validate the narratives (De Massis and Kotlar, 2014).

The first-order concepts enabled the uncovering of the key elements of the informants’ understanding of their family business identity in their own language. We discovered that at this stage, the family businesses were trying to understand “who they are” in different ways. This generated interesting codes, such as “succession plans” and “too small to compete”.

In the second phase, we grouped the refined concepts of the first-order codes into broader themes and patterns regarding family members’ perception of their organization’s identity. In doing so, we carefully considered key elements in a more structured analysis at a higher level of theoretical abstraction (Charmaz and Henwood, 2017). For example, we grouped first-order codes, such as “pivot strategy to ensure longevity” and “abandon family atmosphere” into “new identity formation”. We used constant comparison techniques to identify the second-order themes that subsumed the first-order concepts.

In the third phase of the analysis, we grouped the 11 main themes into five aggregate analytical dimensions reflecting the identity change process. We categorized the three strategies to deal with COVID-19 on the family business identity into “identity stabilizing strategies”. We then further abstracted the theoretical dimensions to provide our own contribution to the literature. The ongoing coding and comparison process began with each interview to generate categorized knowledge then used to improve the questions in the subsequent interviews (Glaser and Strauss, 2017). We used the computer-based qualitative software application Nvivo 12 to support the coding of narratives throughout the process, facilitating the described coding waves, and identifying the overlap between codes. In the following section, we illustrate our findings.

4 Findings

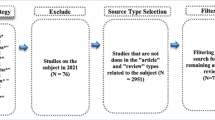

From reading and inductively coding the 23 interviews, 6 validation interviews, and archives from the six cases, we identified competing identity logics and identity inconsistency (before COVID-19), changes in identity context and identity stabilizing strategies during the first encounter (of COVID-19), and co-responding consolidated identity or clarified identity during the new normal (when the companies are adapting to COVID-19). We find that when faced with COVID-19, family firms not only showed strategic flexibility, which influenced their organizational identity. Our findings below explain the five aggregate dimensions emerging from our data (Fig. 1) Footnote 3.

4.1 Identity before COVID-19

Among the first few interviews, two phenomena became apparent: competing identity logics and differently consistent identities. It became clear that the selected firms faced competing family and growth logic, entailing a strategic trade-off between prioritizing family and growth goals. The family firms had variously stable identities before the pandemic: Alpha, Delta, and Epsilon had a uniform and relatively stable narrative of “who we are as a family business”, while, Beta, Gamma, and Sigma underwent strategic changes in a period of 6 months before the COVID-19 pandemic that made them question their understanding of “what we stand for”.

Alpha and Epsilon were characterized by identity consistency, meaning a stable understanding of “who we are as a family business”. Their identity was based on the perception that family takes priority and their long-term orientation focused on maintaining trusting relationships with employees, suppliers, and customers, whereas profit-making was not prioritized. As Alpha and Epsilon relied heavily on the firm’s long-term survival, the ultimate goal was to pass the business to the next generation of family members. The Alpha family CEO said, “Of course, we hope that one of our children will take over the business. […] We are a family business, and we are already the fifth generation, and we live by that”. This is also shown in Alpha’s website section—A family business for generations.

Similarly, Delta built its pre-pandemic identity on its long-term orientation, but with a perception that growth takes priority, regarding itself as a family business that acts professionally and rationally with the ambition to grow steadily and cautiously.

“It is clear to us that we want to grow—we have to get out of this in-between situation between small and medium-sized and You have to differentiate a bit and say yes, we are family-run, we are under the influence of the family, but we are still professional, and we are still profit-oriented” (Delta non-family manager), on their Facebook, they position themselves as “part of a strongly growing medium-sized road construction and civil engineering company with tradition.” (Facebook post Delta, published 09.12.2019, accessed 11.12.2022)

While Alpha, Delta, and Epsilon had a stable understanding of “who are we as a family business”, Beta, Gamma, and Sigma faced identity inconsistency due to changes in competition and strategy occurring in the 6 months before the pandemic, causing a lack of strategic direction. Despite the displaying of a “family” image in public, the family business owners were uncertain about their identity. Although they describe themselves as a “family business” on their website and social media, the family business owners were uncertain about what that meant.

For identity-unstable firms, inconsistency in their self-definition arose from changes in competition, as they operated in a shifting and declining price-driven environment. Under these conditions, the family firms either became smaller players as competitors merged with partners to remain competitive or served clients that were often much larger and financially stronger than the family business. For example, Beta’s CEO commented, “We already had a bit of turbulence in the company in the run-up to the pandemic. […] We simply have a lot of competing products, and demand is declining more and more.”

Second, identity inconsistency occurred due to strategy deviations and the lack of strategic direction. In their narratives, the family business managers revealed their uncertainty about “who are we as a family business” once the business executed strategic shifts. Strategic disorientation stemmed from the changing market conditions for some of the family firms, as they foresaw lower demand for their products, threatening the longevity of the business. Additionally, the unpredictable market situation sparked the question of whether the business should and could remain in the hands of the family.

This identity vagueness was exacerbated when strategic changes were implemented, such as mergers. Indeed, the merger with a non-family firm led Sigma to ask how it could remain true to its values of closeness to employees, open communication, and togetherness.

“We had to rethink, okay, who are we now? And [it] was also a concern that we had when we joined with [the buying group]. Will we be able to keep what we stand for?” (Sigma family CEO)

The analysis of the website and documents published by the family businesses themselves showed that the description of the family businesses refers exclusively to “a family business for generations” (Alpha), “a family business with tradition” (Beta and Epsilon), “owner-managed, traditional family business” (Sigma), and “family business” (Gamma). Only Delta does not describe itself as a family business on its website or other forms of communication.

4.2 First encounter

The unforeseen occurrence of COVID-19 led to family businesses having to fundamentally change their business models, sales strategies, and ways of working. In the process, two phenomena became apparent: identity stabilization and, at the same time, destabilization of the identity of some family businesses.

4.3 Changes in context

From the interviews, it became clear that identity stabilization during the pandemic was accompanied by a simultaneous destabilization of their identity. Just as before the crisis, identity destabilization was triggered by the shifting competitive environment and strategic changes, causing threats to business survival and an increased need to change and adapt. The family firms that challenged their identity the most during the pandemic were those that either sought growth because the pandemic offered growth opportunities or those that implemented strategic changes during or immediately before the pandemic to remain viable.

Since Alpha and Epsilon did not make strategic changes and growth efforts, they only marginally questioned their identity. For example, the former family CEO of Alpha commented: “We could have used the opportunity and also worked with recycled plastic, but that doesn’t suit us. […] we think in the long-term and it wouldn’t have suited us to suddenly track down new suppliers just to be able to sell more in the short-term.”

“We are able to continuously serve our customers keeping our sustainability DNA alive” (internal mail Alpha).

For the family firms with an already unstable identity before the pandemic, inconsistency heightened due to changes in competition, threatening the family business’ survival. As competition intensified, the pandemic forced them to either grow or adjust their portfolio. Indeed, Beta and Sigma were faced with the urgent need to re-evaluate how they wanted to position themselves in the long-term, including which products to offer and whom to target.

“We had to ask ourselves what do we want to do? Whom do we want to serve? Which products do we want to have? And this was caused by the fact that the market changed so much, and customers’ requirements changed so much, and we realized that we should no longer produce certain products” (Beta family CEO)

Second, in the already identity-unstable family firms, inconsistency increased due to strategic changes that increased the need to change and adapt the existing business model.

As the competitive environment changed, strategy adaptation became indispensable, proliferating the urgency for identity-inconsistent family firms to define their identity. In the case of Beta and Delta, both aiming for growth, the question arose as to how much they embodied a profit orientation and how much they sought familiarity. During the pandemic, both firms needed a higher degree of professionalism and profit orientation to enable growth. In the case of Beta, the firm had to ask itself to what extent it was prepared to lay off workers to remain viable in the long run.

“We are not a charity. Yes, we want to keep employees and good contact with suppliers, but not if we endanger the survival of the company” (Next Gen (CIO) at Beta).

“The Corona crisis is forcing many small and medium-sized winegrowers and suppliers to join larger communities after years of price wars.” (excerpt from the annual report of the trade association of winegrowers).

In the case of Delta, the firm questioned to what extent it was prepared to risk its cohesion through growth—“Of course, the family wants to preserve a certain familiarity, but I think we have been at the point for a long time now that we just have to find a way to continue to grow in order to preserve our life’s work.” (Delta non-family managing director).

For Gamma, identity inconsistency was heightened because the firm was aware that to survive in the long term, it needed a partner. But strategic realignment through the merger caused short-term doubts as to whether Gamma could continue to stand for its close connection between family and employees, trust, reliability, and transparency.

“How will communication with our employees change now? Will communication now be handled by [the medium-sized freight forwarder] or will communicate with our lorry drivers remain here at our site? And we thought about it a lot, we had a lot of sleepless nights. And when Corona came, it was a very, very big shock for us. […] At first, we didn’t know what that meant for us” (Gamma family CEO).

This is also shown in Gamma’s internal mail. Further uncertainty about the future strategic orientation arose as the pandemic created the desire to serve smaller customers even if the firm had proudly served large customers for generations.

“This question ‘who are we?’, we asked ourselves a lot. It was also a big discussion within the family because we were always very proud to have big clients and to work with clients who were 10, 20, 30 times as big as we were. […] I kept asking myself, if we stay the way we are now, we are too small for big customers and we won’t survive” (Gamma family CEO)

For Sigma, which had already completed the merger with a larger partner just before the pandemic, answering the question “what do we stand for?” took much less time, in their case in terms of “do we stand for the mass market or are we specialized?” due to the rapidly changing demand situation and simultaneous restructuring the product range.

“During COVID we could have expanded our portfolio and could have tailored our assortment more towards cheaper price ranges, but we just did everything to become more specialized again, so we did not want to lose that” (Sigma non-family managing director).

4.4 Identity-stabilizing strategies

Counterintuitively, we find that the shock caused identity stabilization in that the family businesses gained a clearer understanding of “who they are as a family business” through the shock.

The narratives revealed that identity stabilization was enacted in three strategic ways: retaining the existing identity by intentionally rejecting or embracing growth opportunities, regressing to a previous strategy, or consciously implementing a strategic turnaround to create a new identity.

Reaffirming that they did not want to grow at any cost and striving to maintain their family atmosphere during the pandemic, Alpha and Epsilon achieved identity retention with a focus on family by refusing to take advantage of expansion opportunities from the pandemic. Instead, they highlighted their ambition to maintain their family affiliation. For example, the Epsilon manager stated, “We deliberately don’t want to get bigger now. […] we want to maintain this family atmosphere”.

We also found that identity retention with a focus on growth occurred by advancing a conscious growth strategy. The focus on “we stand for growth and professionalism” was demonstrated not only by increasing the number of employees but also by attaining a higher level of professionalism through non-family managers in leadership positions. For example, a non-family managing director at Delta said, “That’s one thing we also want to signal to our employees by adding [another non-family manager] perhaps: all the signs are pointing to growth, and we want to grow […] we are pretty clear about where we want to go and who we are now”.

“We are in a solid position due to our nationwide customer base and hope to be able to expand this in the first half of 2021” (internal mail Delta)

Gamma and Sigma’s understanding of their identity was clarified by the pandemic in that they decided to strive for identity reconstruction with a focus on family through merging with a partner, which allowed them to go “back to their roots”. This entailed focusing more on family cohesion within the firm and close customer contact to build a stable family-focused identity in the long-term and re-focus on what they specialize in. The non-family managing director at Sigma commented, “Both the pandemic and the merger brought an end to constantly competing on price, but it allowed us to stand for good quality again and good service”.

Beta, however, was forced by the changing market conditions to pivot from its current strategy and adapt it to the changing market conditions by increasing professionalism, efficiency, and internationalization, which caused an identity reconstruction through new identity formation. Through the formation of an entirely new understanding of “who we are” focused on survival, the firm sought to safeguard its financial stability and consequently its longevity.

4.5 New normal

Through the interview, we found that by August 2021 the family firms had established routines and have begun to consider the new way of working as normality, despite the unpredictable length of the pandemic.

Alpha and Epsilon, with a consolidated identity through the shock, reinforced their understanding of their firm’s consistency as their main identity claim and the value of trusting relationships with employees and partners, which is also shown in online articles. For these firms, the crisis confirmed that long-lasting partnerships prevent opportunism even in times of uncertainty. Although the pandemic provided the opportunity to expand, they preferred maintaining their current size so as not to jeopardize cohesion, and retain control.

“We realized again that we want to stand for what we are currently, and we are currently a small family-owned business, and we want to stay like that. We don’t want to grow, […] We have good relationships with our employees and good communication, and […] that is what matters to us” (Epsilon family CEO)

For the growth-oriented family business Delta, the pandemic consolidated its identity in that it intensified its ambition to professionalize, integrated non-family members in the firm (e.g., hiring announcements from an online newspaper article, accessed 20.09.2021, and grew despite the changing competitive landscape during the pandemic.

“We want to grow. Not rapidly, but steadily. We knew that before the pandemic, but now we are once again more aware that we have to grow and invest in order to remain competitive in the long term”(Delta non-family managing director)

For Beta, Gamma, and Sigma, all firms with identity inconsistency in the run-up to the pandemic, the crisis consistently led to clarification of their identity.

In the case of Gamma, the pandemic caused identity clarification as it enabled the firm to resolve its financial worries by merging with a medium-sized family-run partner, thus ensuring its long-term orientation as a small, specialized firm with a strong focus on family affiliation. In so doing, the family ensured control over Gamma, guaranteeing no employees were made redundant, and safeguarding the trusting and long-term relationship with employees.

“[The medium-sized freight forwarder] just has similar values to us. They stand for just as much reliability and just as much sense of responsibility as we do, and it was just a perfect fit (Gamma family CEO)

This reliability for the customer, for the employee and this big family feeling, so to speak […] remained. Even under [the medium-sized transport company] […] we wanted to maintain control over the processes, over customer dealings, over employees” (Gamma head of sales)

For Sigma, the pandemic similarly caused identity clarification, as the pre-pandemic merger with a large purchasing company did not diminish its strong relationship with long-time employees. The Sigma family manager described the merger as “remain[ing] true to our values” and “remain[ing] the small family business that we are now”. The pandemic and the resulting increase in demand additionally manifested in Sigma’s identity claim to not expand but specialize.

“We’ve realized that we are happy with how things are and that we want to maintain the size we have at the moment and rather focus more on the machinery services and on those high-quality products that require detailed consulting” (Sigma non-family managing director)

For both Gamma and Sigma, the shock led to identity clarification in that the mergers were understood as a way “back to their roots”, or as the Gamma family manager put it, allowing him to do “what I actually want, why I’m sitting here”. Instead of dealing with clients that are many times larger than themselves, they could now deal with clients of similar size and values. Both family businesses perceived the mergers as a way of regaining competitiveness while being able to focus on their core business and customers.

“We now can focus so much better on what we are good at and do not have to be concerned about the cost side all the time. I have so much more time now to actually deal with employees and operational things, which I enjoy so much more anyway” (Sigma non-family managing director)

For Beta, the pandemic also caused identity clarification. It became clear from the reduced demand during the pandemic that the family was willing to merge with a larger competitor if necessary and/or hand over management to someone outside the family if there was no successor and thus relinquish control of the firm, or professionalize and restructure parts of the firm to become more cost-efficient. As the Beta family manager put it, “We have to restructure to reduce costs. That is our main priority now after all the Covid mess”. This was also confirmed by her successor, “Covid has clarified to us that we have to do something to remain profitable”. This is also confirmed by industrial sources.

5 Discussion and theoretical contributions

Our research provides novel insights into the interplay between strategy and identity during COVID-19, and the role of strategic responses to changing environmental conditions in the identity transformation process. Through exploring the different behavior propensities and strategic drivers, we found the impact of family influence on business strategic behaviors (Chrisman et al., 2016) through a process model and explained the variances through three propositions. Our findings extend current knowledge of family business identity heterogeneity, and how different identity types contribute to corporate resilience. We discuss the theoretical contributions, limitations, and future research directions below.

5.1 Process model of identity change in family firms during COVID-19

Integrating the findings with the relevant literature, Fig. 2 proposes a model of identity deviation in family firms during shocks, describing the family business identity change process and its relation to strategy during COVID-19.

5.2 Stage 1: identity before COVID-19

Our study proposes two types of family business identities that are variously dynamic and modifiable due to the competing family and growth logic. First, a consistent and stable identity where the strategy and identity are meaningfully aligned (Gioia et al., 2000). Second, an inconsistent identity due to strategic tensions leads to inconsistent interpretations of the identity’s meaning (Corley and Gioia, 2004).

For family firms with a consistent identity, the alignment of the strategy and identity persisted, as no significant changes occurred in the recent family business history. Identity-stable family firms attached great importance to their long-lasting history, highlighting the firm’s longevity and stability.

In contrast, for family firms with an inconsistent identity, strategic tensions, meaning discrepancies between the values at the base of the identity and goals pursued through a strategy, caused inconsistent interpretations of the identity meaning (Smith and Besharov, 2019).

5.3 Stage 2: first encounter

As a reaction to the changing competitive situation caused by COVID-19, identity-consistent family firms persisted with their identity despite temporal identity questioning arising from minor strategic tensions. Family firms with a previously non-stable identity experienced both simultaneous stabilization and destabilization during the pandemic. In the following, we discuss the factors that contributed to identity destabilization, and how the family business leaders reacted to their identity change requirements.

5.3.1 Competition

Although they noticed the changes in competition, identity-stable firms adhered to their long-term strategy. However, for previously identity-unstable family firms, the exogenous shock triggered strong strategic tensions leading to identity reconstruction and strategy adaptation. The family businesses had to reconstruct their desired self-definition of how they saw the business in the future and whether their current strategy matched the changing competitive conditions. These inconsistencies between the current identity and how it should be in the future (Corley and Gioia, 2004) intensified as the strategic change caused disparities between the firm’s desired identity and the necessary strategic changes (Ravasi and Schultz, 2006).

5.3.2 Change in strategy

The changing competitive environment resulted in three strategic choices strengthening the family businesses’ identity during COVID-19: (1) retaining their current identity and strategy (Alpha, Epsilon, Delta—Proposition 1), (2) regressing to a previous identity and strategy (Gemma and Sigma—Proposition 2), and (3) strategic turnaround to establish a new identity (Beta—Proposition 3).

5.3.3 Retaining the original identity

For identity-stable family firms, this identity retention with a focus on either growth or family was enabled through self-legitimization, which consists of family business leaders reinterpreting the existing identity and strategy, justifying its retention solely by emphasizing its positive impact on the business (He and Balmer, 2007). The family thus acted as a “keeper of the past” (Micelotta and Raynard, 2011, p. 204), allowing the family firm to maintain continuity in the face of change (Maclean et al., 2018). Despite the changing conditions, such as growth opportunities, family businesses with a consistent identity and strategy re-enforced their original strategy and identity. For example, Delta retained its identity focused on growth, while Alpha’s interest is long-term survival with a focus on family succession. As highlighted by Lumpkin and Brigham (2011), the long-term orientation of family firms represents an overarching heuristic that provides a dominant rationale for decisions and actions. We theorize the impact of COVID-19 as a type of exogenous shock, forcing SMEs to strategically respond (Shepherd and Williams, 2022). Although identity enforcement, i.e., the preservation of a consistent sense of what the organization stood for and stands for, can result in missed business opportunities, the elaboration or reformulation of prior claims can cause stability during times of change (Cloutier and Ravasi, 2020; Harikkala-Laihinen, 2022). Thus, we propose the following:

-

Proposition 1. Faced with exogenous shocks, such as COVID-19, family firms with a consistent identity and strategy remain focused on their pre-shock identity, either family or growth-focused.

5.3.4 Identity reconstruction with a focus on family

In identity-inconsistent family firms, identity stabilization was achieved through identity reconstruction focused on the entrepreneurial activities and values that were previously important to the family. This reinterpretation of the identity through interpreting the past for the present led to building an identity inspired by a previous identity (Schultz and Hernes, 2013) and the family firm’s history (Ge et al., 2022).

For example, Sigma secured an exclusive contract with a supplier during the pandemic, which freed the firm from its financial worries and allowed concentrating on how the family wanted to be perceived, namely as a specialized small family firm. Gemma merged with another family business to keep employees and continue doing what they do for generations. We extend existing research (e.g., Schultz and Hernes, 2013; Ge et al., 2022) on the use of past influences on the articulation of claims for a future identity, by highlighting that during shocks, through recalling strategy and business practices from the past, family businesses find new strategic directions by orienting themselves towards a previous identity (Micelotta and Raynard, 2011). Similar to Bövers and Hoon (2021), we find that by “going back to the roots”, the family business reconstructs an identity that existed in the past, focused on the family and the distinctiveness of the business. Thus, we propose the following:

-

Proposition 2. Faced with exogenous shocks, such as COVID-19, with a clear solution for financial difficulties and competition, family firms with an ambiguous identity will resort to identity reconstruction with a focus on family.

5.4 New identity formation

We found this change predominantly in family firmsFootnote 4 that struggle between their perceptions of “who we are as a family business” and competitiveness in a rapidly changing and reduced market during COVID-19. As a result, they changed their strategy to form a new identity that is opportunistic and focused on survival. For example, faced with alarmingly shrinking market competitiveness, Beta undertook a strategic change by abandoning or “betraying” (Phillips and Kim, 2009, p. 497) its family business identity, completely moving away from its family values during the pandemic and towards growth-focused identity (Wiklund et al., 2003). This strategy ensured the firm’s survival but came at the cost of losing its family business identity. As a result, the incumbent and successor both expressed an interest in selling the business in the next 5 years. Although we did not observe the opposite, we theorize that this opportunistic behavior that results in a new identity can evolve toward both a family and growth-focused strategic direction. According to Davidsson (1989), the expectation of financial reward and greater independence (the prospect of a reduction in external dependencies) are the greatest motivators to seek growth for SMEs. Over time, modifications to family businesses’ meta-identity in response to a changing environment allow for strategic flexibility, thus positively contributing to the long-term survival of the family business (Reay, 2009). By disconnecting their identity from the past, family firms can establish a new identity which is primarily focused on financial development (Micelotta and Raynard, 2011). Through this growth-oriented identity, business objectives such as profit maximization and business growth provide the orientation for the new strategy (Ponomareva et al., 2019). Thus, we propose the following:

-

Proposition 3. Faced with exogenous shocks, such as COVID-19, without a clear solution for survival, family firms with an inconsistent identity will resort to opportunistic behavior to form a new identity for survival, disregarding the original family business values.

5.5 Stage 3: new normal

The model emerging from our analysis points to three types of family business identities arising from an exogenous shock—COVID-19.

First, consolidated identity with a retained strategy, whereby during a shock, family businesses strengthen their understanding of “the central and enduring attributes of [their organization] that distinguish it from other organizations” (Albert & Whetten, 1985, p. 80).

Second, clarified identity with identity restoration and an adapted strategy, which describes a family firm identity that through the shock returned to a previous identity, anchoring elements of past identity claims in their strategic orientation. Due to the shock and the resulting financial distress, these family businesses focus on a meta-identity based on re-establishing a family atmosphere and preserving family values rather than pivoting their business for the sake of profits.

Third, clarified identity with new identity claims and a new strategy, which emerges as competition forces the family firm to professionalize, not based on a past identity but aimed at a complete reorientation of the family business. This identity type comprises a reduced family presence in the business to ensure the firm’s survival, pivoting the family values toward a stronger focus on efficiency, professionalization, and either a merger, aggressive growth, downsizing, or profound restructuring.

Joining a growing stream of research on the impact of exogenous shocks, especially the COVID-19 pandemic on family businesses (e.g., Belitski et al., 2022; Hadjielias et al., 2022; Miroschnychenko et al., 2023), our research shows that an exogenous shock provides the opportunity for family businesses with a clear or inconsistent identity to reflect on their desired identity and re-focus their strategy. We thus demonstrate that successful identity management is not about preserving a fixed identity but the ability to balance a flexible identity amid shifting external conditions (Gioia et al., 2000). Further, we contradict the notion that family firms with a strong emphasis on family logic may be less entrepreneurial (Arzubiaga et al., 2018; Schepers et al., 2014). Rather we show that a clear focus on the family can serve as a guideline during an exogenous shock.

5.6 Strategy/identity dynamics during exogenous shocks

The proposed identity change process model refines our understanding of organizational identity in family businesses in the context of strategic deviations during exogenous shocks (Whetten et al., 2014). Through our model, we highlight that surprisingly, exogenous shocks, which are typically always described as evil (e.g., Adian et al., 2020; Chowdhury, 2011), can also have positive effects on (family) businesses. Exogenous shocks can lead to the stabilization and consolidation of organizational identity. Our study also extends knowledge of family business identity/strategy dynamics through two key theoretical contributions explaining how identity and strategy influence and rely on each other (He and Balmer, 2013).

First, our findings provide insights into the interplay of identity and strategy by depicting how diverse identity types are affected by exogenous shocks (Kreiner et al., 2015). We reveal that exogenous shocks compel family businesses to not only re-evaluate their environment (look out), but above all to re-evaluate their own identity and what they want to stand for in view of the changing external conditions (look in).

In particular, our study suggests that a stable identity is not changed but strengthened by an exogenous shock, as the strategy is retained, while an inconsistent identity is further destabilized as strategic changes are executed, and comparable businesses deviate. To alleviate the identity inconsistency heightened by a shock, identity-inconsistent firms that are focused on family affiliation reconstruct their identity by connecting their desired identity to a past identity, while family businesses are forced to enhance their professionalization, adjust their identity, and abandon their family affiliation. Consequently, the effects of a shock on identity depend on the firm’s identity stability. The identity-reconstruction response in turn depends on the prominence of the family identity in the family-business meta-identity.

By highlighting the drastic interplay between strategy and identity as a means of identity deviation (He and Balmer, 2013), this study closes the identified research gap in three ways: revealing how and under which conditions family businesses’ organizational identity shifts during exogenous shocks (De Massis and Rondi, 2020); responding to the call of Ponomareva et al. (2019) to investigate what triggers firms to adopt a new identity; and illustrating how diverse identity types influence different strategic decisions (Ravasi et al., 2020).

5.7 Family business identity heterogeneity

Second, our research enriches the knowledge of family and business identity heterogeneity by providing evidence that a growth-focused identity, similar to a financial identity (Ponomareva et al., 2019), emerges when survival with a family-focused identity is no longer possible in view of price competition intensified by the pandemic. Consequently, our study shows that a dynamic growth-oriented family-business identity fosters greater economic advantages in a highly competitive or shrinking market environment, particularly effective in businesses at later stages of the family lifecycle when intra-family success becomes less relevant (Ponomareva et al., 2019). This view on the heterogeneity of identity in family businesses builds into an ongoing debate on the paradoxical tensions in family business goal systems (e.g. Barrett and Moores, 2020; McAdam et al. 2020). We explain that, facing the uncertainty of external challenges like COVID-19, the competing family business goal systems face more challenges and provide an opportunity for family business owners to refine and re-define the identity of the family businesses (Diaz-Moriana et al., 2022).

5.8 Research limitations and future research directions

Our research ventures into the underinvestigated, socially complex field of organizational identity research. Despite its exploratory nature, we note some limitations that also provide opportunities for future inquiry.

First, our research casts some light on understanding the strategic flexibility of family firms relating to the use of the past (Bövers and Hoon, 2021; De Massis et al., 2016). However, due to the research focus and scope, we did not explore this further.

Second, our sample size of six German “Mittelstand” cases could potentially limit generalizability. Companies in Germany received financial support from the state in the short term after the shock (Federal Government Germany, 2020), it can be assumed that family businesses in other countries faced different challenges and opportunities resulting from the exogenous shock. It would be interesting to see if family businesses in other countries have different strategy-identity dynamics.

Third, we explored a specific exogenous shock, COVID-19, for family business identity. However, family businesses have many competing goals and goal tensions during different times of stress/crisis both internal and external (see calls for SMEs’ response to unforeseen shocks, e.g., Fairlie et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022).

We propose further studies to explore from identity and use of past perspective, that past allows the family businesses the flexibility, especially in expressing their choice of strategic changes in identities, for family owners to manage and strategically position the business (Ge et al., 2022; Suddaby et al., 2020), to “address the trade-offs between continuity and change over time” (Sasaki et al., 2020, p. 619), and to adapt or shift competitive conditions during a shock matches existing identity claims (Ravasi and Schultz, 2006).

Another promising direction for future research refers to further unpacking how different dynamics and firm characteristics such as age on the identity and goal system of family firms (e.g., Barrett and Moores, 2020; McAdam et al. 2020). For example, considering the unique outcome of Beta, future research could utilize an in-depth single case study to understand unique (and counter-intuitive) cases of the interplay between the family business and strategic changes under exogenous shocks.

Future research could expand the cases to include family firms with internal changes, such as succession, during exogenous shocks to understand the succession and family business identity dynamics. Internal changes, such as succession, retirement, entry of family members, and procedural changes, such as selling parts of the firms are all considered important drivers of identity ambiguity (Corley and Gioia, 2004). It would also be interesting to look at identity over a longer period of time (e.g. over several generations) since identity stability can only ever be achieved temporarily and is frequently up for redefinition and revision by the organization’s members (Gioia et al., 2000).

Also, to better understand the influence of shocks, we encourage future research to explore the impact of internal shocks, for example, the (sudden) death of a founder (Heinonen and Ljunggren, 2022; Vincent Ponroy et al., 2019) as well as external shocks, for example, war (Widmaier et al., 2007) or natural disasters (Auzzir et al., 2018; Salvato et al., 2020). Last, due to the qualitative nature of our study, we propose but do not test our three propositions. Hence, it would be interesting to conduct further quantitative research on a larger scale to test these propositions and thus contribute to fine-grained theory-building.

Notes

Please see attached interview guideline.

We carefully considered the use of website information due to: (1) the websites of the family businesses (SMEs) are, in general, outdated and (2) We consider a website as a representation to the outside world, which is of limited support for our inquiry of identity, which is internally oriented.

Additional examples from our interviews are archives provided in Table S1 in the supplementary document.

With respect to proposition 3, we understand that to mitigate the potential risk of data shortage. We try to address this by adding on an informal conversation with another family firm that is in a similar situation to Beta. From these informal interviews we found confirmation that COVID-19 caused family firms without a clear solution for survival with an inconsistent identity to resort to opportunistic behavior to form a new identity for survival, disregarding the original family business values. Information about these interviews is available upon request. In addition, we conducted observations of publicly available secondary data from newspapers, annual reports, and websites to check whether the behavior proposed in proposition 3 occurred in other family firms.

References

Adian, I., Doumbia, D., Gregory, N., Ragoussis, A., Reddy, A., & Timmis, J. (2020). small and medium enterprises in the pandemic: Impact, responses and the role of development finance. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-9414

Albert, S., & Whetten, D. A. (1985). Organizational identity. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings, (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (pp. 263-295). Greenwich: JAI Press.

Anthony, C., & Tripsas, M. (2016). Organizational identity and innovation. The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Identity, 1, 417–435.

Ashforth, B. E. (2020). Identity and identification during and after the pandemic: How might COVID-19 change the research questions we ask. Journal of Management Studies, 57(8), 1763–1766. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12629

Arzubiaga, U., Kotlar, J., De Massis, A., Maseda, A., & Iturralde, T. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation and innovation in family SMEs: Unveiling the (actual) impact of the board of directors. Journal of Business Venturing, 33(4), 455–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.03.002

Audretsch, D. B., & Lehmann, E. (2016). The seven secrets of Germany: Economic resilience in an era of global turbulence. Oxford University Press.

Auzzir, Z., Haigh, R., & Amaratunga, D. (2018). Impacts of disaster to SMEs in Malaysia. Procedia engineering, 212, 1131–1138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2018.01.146

Balmer, J. M. (2008). Identity based views of the corporation: Insights from corporate identity, organizational identity, social identity, visual identity, corporate brand identity and corporate image. European Journal of Marketing, 42(9–10), 879–906. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560810891055

Balmer JM and Greyser SA (1995) The 1st Strathclyde statement, available at https://www.icig.org.uk/the-1st-strathclyde-statement (accessed 2 August 2021).