Abstract

While academic entrepreneurship depends on the entrepreneurial behavior of university scientists, management studies show that identity development precedes behavioral enactment. This paper extends our understanding of why and how individuals who define themselves as a scientist develop or fail to develop a new commercialization-focused entrepreneurial identity. We develop an explanatory process model by drawing from the concept of liminality, a transitional state during which individuals construct or reconstruct an identity, as well as the entrepreneurship literature. The model not only provides a stylized illustration of identity development and its associated behavioral outcomes, but it also includes several factors such as agency and passion, liminal competence, social support, organizational and institutional support, and temporal factors that moderate the process. We contribute to the literature on entrepreneurial identity by providing a dynamic conceptualization of identity construction and incorporation, among other outcomes, as well as to the academic entrepreneurship literature by elucidating the origin and development of entrepreneurial identities among scientists. A conceptual focus on identity-related micro-processes may help explain why some scientists are more successful at commercializing technologies derived from their research than others. Implications for theory and future research are discussed.

Plain English Summary

This article explains how scientists develop a new entrepreneurial identity and the factors responsible for the successful (or unsuccessful) identity-related transition that enables commercialization of new technology derived from scientific research. The involvement of scientists, including faculty, postdocs, and graduate students, is crucial for the transformation of scientific knowledge and technology into commercialized products and services. These individuals generally possess a strong professional identity as a scientist, which can constrain their involvement in entrepreneurial activities. Drawing from research on both professional identity and academic entrepreneurship, this article introduces a conceptual model that explains how and why scientists develop (or fail to develop) a new commercialization-focused entrepreneurial identity. The article also provides a template for future empirical research that not only tests its findings but might also provide a richer understanding of barriers and enablers to entrepreneurial identity development. Such knowledge is crucial for policy and programmatic interventions that seek to promote academic entrepreneurship and therefore increase the economic impact of research universities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Identity is defined as “a self-referential description that provides contextually appropriate answers to the question ‘Who am I?’ or ‘Who are we?’” (Ashforth et al., 2008, p. 327). Empirical research demonstrates that entrepreneurial behavior depends on entrepreneurial identity centrality, the subjective importance of an identity relative to other professional identities (Farmer et al., 2011; Fauchart & Gruber, 2011; Hoang & Gimeno, 2010). The more central an entrepreneurial identity, relative to other identities, the more an individual will develop passion for their venture (Murnieks et al., 2014), attempt to grow and sustain their startup (Farmer et al., 2011), and develop the capability to identify and pursue market opportunities (Fauchart & Gruber, 2011).

University scientists, including faculty, postdoctoral fellows (postdocs), and graduate students, confront growing expectations to engage in academic entrepreneurship, the commercialization of technologies derived from university research (Siegel & Wright, 2015). While studies show that scientists may lack the requisite skills, resources, and social networks (Hayter et al., 2018), their purposeful engagement is among the most critical factors for successful technology commercialization (Rasmussen et al., 2011).

The compatibility and interaction of multiple personal and professional role identities impacts the behavioral enactment of each (Ladge et al., 2012). Pioneering research attributes commercialization-related behavior among scientists to the construction of a hybrid role identity that balances both scientific and entrepreneurial responsibilities (Huyghe et al., 2016; Jain et al., 2009). However, like orchestral musicians (Faulkner, 1973), elite military units (Thornborrow & Brown, 2009), and airline pilots (Fraher & Gabriel, 2014), scientists possess a strong professional identity that usually remains central even after developing a new identity as a commercialization-focused entrepreneur (Jain et al., 2009).

Of course, scientific and entrepreneurial identities share overlapping attributes, such as networking, project management skills, and ability to discover, evaluate, and exploit opportunities that, following the identity literature (e.g., Ashforth et al., 2000) ease the transition between and support the behavioral enactment of both (O’Kane et al., 2020). Scientists nonetheless experience internal conflict between scientific and commercialization-oriented goals (Ambos et al., 2008; Meek & Wood, 2016) and are socialized and work in departments that, despite growing institutional and policy emphasis on commercialization, may not support fully, or even constrain, entrepreneurial identity development (Hayter, 2016a; Klingbeil et al., 2019). Further, academic entrepreneurship scholars have yet to conceptualize how and why academic scientists develop and behaviorally enact that identity or, perhaps equally important, why do they not (Balven et al., 2018; Hmieleski & Powell, 2018).

This paper introduces liminal venturing as a novel framework to explain the process of entrepreneurial identity development among individuals who already possess a strong central identity as an academic scientist. Our framework builds upon the concept of liminality, a transitional state during which individuals construct or reconstruct an identity, especially what Söderlund and Borg (2018) term “liminality as process.” Liminality-based concepts are increasingly employed by identity scholars to frame important managerial and policy issues and other types of professional transitions, such as work role loss (Conroy & O’Leary-Kelly, 2014), contract or temporary employment (Tempest & Starkey, 2004), pregnancy among professionals (Ladge et al., 2012), and, recently, entrepreneurial development (Callander & Cummings, 2021; Prashantham & Floyd, 2019).

The theoretical potential of liminality and its affiliated processes lies in their emphasis on how identity development occurs as well as why, including the role of specific factors that spark and moderate identity development and influence whether or not individuals achieve identity re-incorporation (Ibarra & Barbulescu, 2010). Re-incorporation, what Rogers and colleagues (2017) term identity holism, is a developmental outcome whereby individuals either reconcile aspects of old and new identities so they may co-exist, or instead exit from a new or existing identity completely (Ebaugh, 1988; Petriglieri, 2011). Scholars conceptualize reincorporation as an intermediate outcome that is especially relevant to academic entrepreneurs who themselves must reconcile their existing scientific and new entrepreneurial identities so that commercialization-focused behavior may occur (Jain et al., 2009). Finally, liminality-based research frames the behavioral enactment of an identity as a function of how individuals experience the identity development process, including supportive (or constraining) contextual factors.

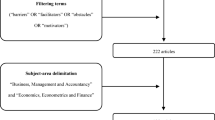

Figure 1 provides a conceptual illustration of our liminal venturing process model as well as factors that moderate the process, including agency and passion, liminal competence, social support, organizational and institutional support, and temporal factors. While liminal venturing is derived primarily from the management-oriented identity literature, we demonstrate the potential efficacy of the model with observations from entrepreneurship research, especially academic entrepreneurship. Specifically, we integrate insights from the entrepreneurship literature that demonstrate how identity related concepts can frame and explain academic entrepreneurship outcomes.

We make two main contributions. First, we contribute to the entrepreneurial identity literature by theorizing how an individual with a strong central identity (in our case, scientist) develops a commercialization-focused entrepreneurial identity (or not), incorporates that identity into their existing self-concept (or not), and the degree to which they behaviorally enact that identity. Prior studies examine how a focal identity forms (e.g., how an individual who goes to business school develops a business mindset), and scenarios within which individuals may potentially transition to a different identity (e.g., entrepreneur, see Haynie & Shepherd, 2011). In this paper, we provide a dynamic conceptualization of the identity development process, especially relating to how identities emerge, interact, and evolve collectively over time, that can be used by scholars to frame and study a variety of entrepreneurial identity development scenarios.

Second, specific to academic entrepreneurship, we theorize as to how scientists balance academic and commercial roles, transitioning from one to the other (or not), and the moderating impact of contextual and temporal factors during this liminal venturing process. By extending discussions on the importance of identity beyond one point in time (Huyghe et al., 2016; Jain et al., 2009), our liminal venturing process model also elucidates how entrepreneurial identities occur and develop temporally. By this, we contribute to scholarly understanding of why some scientists may be more successful commercializing their research than others. Understanding the origins, support environment, and triggers leading to a transition from a scientific to an entrepreneurial identity, and the potential interplay between, has important implications for practice, as well as management and policy interventions that seek to cultivate and support academic entrepreneurship (Jain et al., 2009).

2 Liminal identity development

To provide the conceptual foundation for our liminal venturing framework, this section describes the concept of liminality, constituent concepts of identity work and identity play, and outcomes of liminality.

2.1 Liminality

Liminality is a transitional state through which identities are developed (Beech, 2011). The term was originally created by anthropologist Arnold van Gennep (1909) to describe a rite-of-passage from adolescence to adulthood in indigenous populations (Söderlund & Borg, 2018). Söderlund and Borg (2018) posit that van Gennep’s original rite-of-passage, what we term a liminal process, was comprised of three phases including (1) a separation or detachment from one’s existing environment and routines, (2) a liminal phase whereby individuals experience an uncertain yet temporary transition as a result of natural and evolutionary cues, and (3) a final reaggregation or reincorporation phase that signifies a new, stable status in society, resulting in a new, progressive identity. Though individuals experience uncertainty and anxiety, conceptualization of the original liminal transition included a culturally legitimate narrative to govern the process, guidance by elders, and a supportive cohort of fellow liminars, though these supportive elements are often missing from identity-related experiences, especially within contemporary organizations (Ibarra & Obodaru, 2016).

Turner (1967, 1977) develops further the liminality concept to describe individuals in transition who have no defined or recognized social position and are thus suspended between two identities (Ibarra & Obodaru, 2016), what Turner (1967, p. 96) terms “betwixt and between.” Management scholars have since appropriated the term to investigate identity-related phenomena within modern organizations. Scholars have over time improved the utility of liminality as a theoretical construct, though more detailed accounts are needed to explain how liminality occurs within different contexts (Ibarra & Obodaru, 2016; Söderlund & Borg, 2018). Understanding liminal processes is especially important given that identity development is a ubiquitous human experience, has implications for emotional and physical health and well-being (Petriglieri, 2011; Thoits, 1983), and can guide individual and managerial interventions (Ibarra & Obodaru, 2016).

2.2 Identity play and work

According to Ibarra and Obodaru (2016), the liminal process can be categorized, based on purpose and process, into identity play and identity work (also see Ibarra & Petriglieri, 2010). Identity play is defined as “people’s iterative engagement in provisional trials of possible future selves” (Ibarra & Petriglieri, 2010, p. 11). In other words, identity play is associated with self-exploration whereby individuals experiment with new and different versions of who they would like to become (Beech, 2011; Sturdy et al., 2006; Tempest & Starkey, 2004). Given that individuals can possess multiple identities, so too can they possess many possible selves, though most are amorphous and daydream-like (Farmer et al., 2011). As a possible self emerges, it is tested against internal and external standards and often discarded. Or, if an individual commits to the identity, the provisional identity becomes aspirational thus motivating identity work whereby an individual must learn the norms and practices of a particular group (Farmer et al., 2011; Ibarra, 1999). Provisional identities are therefore “akin to trying on different clothes and seeing what fits” (Ibarra & Obodaru, 2016, p. 59).

Scholars attribute identity play to human creativity and agency whereby individuals choose to construct a notional identity, not necessarily claim or have others grant their identity (Ibarra & Petriglieri, 2010). Conversely, individuals may choose not to undertake identity play or fail to pursue further an emergent identity (Fraher & Gabriel, 2014; Haynie & Shepherd, 2011; Rogers et al., 2017). Identity play is facilitated through freedom from existing ways of thinking and doing which, in turn, enhances creativity (Sturdy et al., 2006; Tempest & Starkey, 2004). Scholars therefore recommend that managers implement interventions and policies that facilitate and guide identity play toward a progressive outcome that aligns with the goals of their organization (Ibarra & Obodaru, 2016; Kahn, 2001).

Identity work is an individual’s engagement in forming, repairing, maintaining, strengthening, or revising an emerging or existing central identity (Ibarra & Petriglieri, 2010; Pratt et al., 2006). While identity play connotes exploration through a provisional self, identity work implies that an individual has embraced a particular identity and committed to develop it further. The relationship between identity play and work is non-linear, iterative and reflexive; no clear boundary exists. However, the extent to which an individual engages in identity work is represented by their relative commitment to the identity of interest (Turner, 2013).

Though scholars have yet to explore the transition from identity play to work, research empirically examines how identity work is triggered. Specifically, identity work can occur due to identity threat sparked by traumatic events or “experiences appraised as indicated potential harm to the value, meanings, or enactment of an identity” (Petriglieri, 2011, p. 644) that, in turn, necessitate identity construction or reconstruction (Ashforth & Schinoff, 2016). For example, studies investigate identity threats among pilots furloughed due to the economic shocks surrounding both 9/11 and the 2008 financial crisis (Fraher & Gabriel, 2014), soldiers experiencing trauma as a result of an improvised explosive device or gunshot wounds (Haynie & Shepherd, 2011), and job loss among matured-aged workers due to corporate downsizing or restructuring (Beech, 2011).

Identity work may also be triggered by dawning or epiphany, the gradual realization that one’s identity is misaligned with their work role or environment (Kira & Balkin, 2014). Individuals experiencing this type of identity threat may believe their career is plateauing or stagnating (Dutton et al., 2010) or feel that they are no longer trusted or accepted by their peers (Petriglieri, 2011; Pratt et al., 2006). Dawning occurs over time in an existing job or may result from a change of job or organizational restructuring (Beech, 2011; Ibarra, 1999; Ibarra & Petriglieri, 2010; Pratt et al., 2006). Finally, identity work occurs as individuals adopt a new identity due to socialization, a response to the collective expectations of a professional group, such as a British Paratrooper Regiment (Thornborrow & Brown, 2009), specialized physician sub-field (Pratt et al., 2006), or management consultancy (Sturdy et al., 2006).

2.3 Liminality outcomes

For liminal individuals, a desirable outcome is (re)incorporation, what Rogers et al. (2017) term holism, an identity development end-state that provides a coherent sense of self that influences work performance positively (Conroy & O’Leary-Kelly, 2014; Ibarra & Barbulescu, 2010; Pratt et al., 2006). When an existing identity is revised or a new identity created, reincorporation occurs when individuals find ways to reconcile aspects of old and new identities so they may co-exist (Petriglieri, 2011). Fraher and Gabriel (2014) show, for example, that furloughed airline pilots developed a new professional identity within aviation so they could regain control over their professional lives while integrating aspects of their previous identity.

Among individuals who achieve incorporation, the degree to which a new identity is enacted behaviorally can vary substantially. Ladge and colleagues (2012) find, for example, that while many expectant mothers plan to scale back time devoted to their role as a working professional and devote more time to their parental responsibilities, others nonetheless seek to “have it all,” defining their roles equally. Further, a small percentage of women seek to protect and maintain their professional identity, demonstrating only minimal interest in enacting their identity as a parent, at least prior to pregnancy, potentially indicating that they have not achieved holism. As discussed, individuals might also choose to enact few aspects of their former identity, though it remains a part of their self-concept (Petriglieri, 2011).

Among individuals who do not achieve identity incorporation, liminality may endure maladaptively with significant personal costs (Ibarra & Obodaru, 2016). The inability or unwillingness to complete the liminal process leads to individuals feeling stuck or trapped (Beech, 2011; Conroy & O’Leary-Kelly, 2014; Petriglieri, 2011). Empirical research highlights this notion of “permanent liminality” (Johnsen & Sørensen, 2015) among individuals who have experienced life-altering injuries (Haynie & Shepherd, 2011) or chronic and temporary unemployment (Boland & Griffin, 2015). Individuals who cannot complete the liminal process may experience significant cognitive and emotional loss, low self-esteem, shame, withdrawal, and stigmatization (Conroy & O’Leary-Kelly, 2014; Fraher & Gabriel, 2014; Kira & Balkin, 2014). Worse yet, individuals may choose to exit an identity and abandon the liminal process without constructing an alternative identity or undertaking restorative coping that can provide a sense of purpose, meaning, and connection (Ibarra & Obodaru, 2016; Petriglieri, 2011; Thoits, 1983).

3 Contextualizing entrepreneurial identity development among scientists

The purpose of the liminal venturing model is to explain why and how a commercialization-focused entrepreneurial identity develops among individuals who already possess a central professional identity as a scientist. This section provides conceptual background needed to explain identity development within the context of academic entrepreneurship, from origination through various behavioral outcomes (discussed in Sect. 4). It does so by drawing from both identity development and entrepreneurship literatures to derive five interrelated factors, defined in Table 1, including entrepreneurial agency and passion, liminal competence, social support, organizational and institutional support, and temporal factors. The subsections below describe and subsequently frame each factor within the liminality-as-process literature to establish the conceptual foundations of our model.

3.1 Entrepreneurial agency and passion

Scholars have traditionally focused on entrepreneurial motivations and, more recently passion, to explain entrepreneurial behavior. Murnieks et al., (2020a, b) define entrepreneurial motivation as “[E]nergetic forces that originate within as well as beyond individuals to initiate behavior and determine its form, direction, intensity, and duration” (p. 115). Academic entrepreneurship scholars have drawn from self-determination theory (SDT) to investigate intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for entrepreneurial behavior (Lam, 2011). Intrinsic motivations are based on individual interest, enjoyment, and altruism, while extrinsic motivations stem from separable consequences, such as recognition, penalty avoidance, and financial reward (Deci et al., 2017). Studies show, for example, that scientists derive intrinsic satisfaction from learning about entrepreneurship, developing entrepreneurial skills, and engaging in the application and transfer of knowledge (Lam, 2011). Academic faculty also establish spinoff companies for altruistic reasons, such as providing employment for their students or their local region (Hayter, 2011).

Extrinsic motivations can also take the form of recognition and financial incentives (Lam, 2011). Recognition may include acknowledgement from peers within the scientific community (Lockett & Wright, 2005) or commercialization-related criteria for tenure and promotion (Grimaldi et al., 2011). Motivating financial incentives include licensing revenue sharing and IP ownership schemes (Kenney & Patton, 2011), or the general desire to benefit financially from one’s entrepreneurial effort (Lam, 2011). Doctoral students and postdocs, especially those who are unable to find tenure-track faculty positions, are entrepreneurially motivated by the opportunity to build an alternative career (Hayter & Parker, 2019).

While studies of entrepreneurial motivations among scientists have yet to be framed in terms of a liminal process, Lam’s (2011) utilization of SDT provides a conceptual bridge to recent identity-related studies of passion, defined as a “motivational force” and “strong inclination toward certain activities” (Murnieks et al., 2014, p. 1584); passion encompasses the intensity of entrepreneurial motivations. In their review of the entrepreneurial motivations literature, Murnieks et al., (2020a, b) similarly show that passion is not only related to early-stage entrepreneurial motivations, it also remains important throughout venture growth and exit phases. Huyghe and colleagues (2016) empirically demonstrate that entrepreneurial passion among scientists drives entrepreneurial intentions, an antecedent to entrepreneurial behavior. Murnieks and colleagues (2014) posit that passion not only motivates entrepreneurial behavior, but their relationship is also reciprocal; passion may motivate identity development, just as identity centrality may ignite passion (see also Murnieks et al., 2020b). Other scholars hold that entrepreneurial action may precede and drive entrepreneurial passion (Collewaert et al., 2016).

Entrepreneurial passion can be reconciled with SDT by focusing on its conceptual relationship with intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, and how resultant behavior is autonomous or controlled (Deci et al., 2017). According to Deci et al. (2017), autonomy is important for self-worth, higher job performance, and better learning and adjustment outcomes. Autonomous behavior is motivated by intrinsic interest as well as the authentic and autonomous internalization of extrinsic motivations, while behavior can be internally or externally controlled through extrinsic contingent rewards, power dynamics, and other separable consequences. Murnieks et al., (2020a, b) similarly describe entrepreneurial passion as harmonious if entrepreneurship activities are engaged willingly and free of contingency, whereas passion is obsessive if an individual feels compulsion to engage in activities for the ego affirmation provided. In sum, motivations and passion are distinct, yet interrelated components of identity development.

Framed within the liminality-as-process literature, agency—not motivations per se—is the critical explanatory factor for determining whether an individual undertakes entrepreneurial identity work, including through initial engagement in identity play and subsequent commitment to identity work, or by being propelled with little choice into entrepreneurial identity work through a controlling event or scenario. Agency also helps explain why a scientist may choose not to undertake entrepreneurial identity leading to commercialization inaction. Further, passion may be viewed as a proxy for the degree to which an individual has developed and maintains an entrepreneurial identity relative to their scientific identity, regardless of the original rationale for undertaking identity work. For example, a postdoc might choose to pursue academic entrepreneurship out of necessity yet choose to develop a central entrepreneurial identity over time and thus exhibit high levels of entrepreneurial passion (see Murnieks et al. 2020b).

3.2 Liminal competence

An individual’s ability to undertake and successfully complete the liminal process is dependent on liminal competence, defined as the specific skills and personal narratives required to enact a desired identity (Meek & Wood, 2016; Pratt et al., 2006). Liminal competence is developed through educational and professional experiences, including professional training, participating in unique work projects, or experience from working in a variety of careers. Haynie and Shepherd (2011), for example, find that some soldiers injured during battle subsequently developed entrepreneurial identities by connecting the knowledge, skills, and habits gained during their military training and experience with those required to launch a new venture.

The emergence and growing centrality of an entrepreneurial identity increases the relative strength of entrepreneurial aspirations (Farmer et al., 2011) and associated commercial outcomes (Shepherd & Haynie, 2009). One’s self-conception as an entrepreneur also drives the acquisition of skills and networks required to actuate that role (Ibarra, 1999), including opportunity recognition (Ardichvili et al., 2003), new product and service development (Ward, 2004), coping and stress management (Uy et al., 2013), resource leveraging (Rasmussen & Wright, 2015), adaptive skills (Sexton & Bowman, 1985), and marketing knowledge and business planning competences (Hood & Young, 1993), among others. In other words, liminal competence is conceptually distinct, but related to individual and organizational competencies.

Academic entrepreneurship studies show that entrepreneurial competencies are also critical to spinoff establishment and performance (Grandi & Grimaldi, 2005). Competencies enable scientists to leverage resources, transform and refine observed opportunities into viable business concepts, and motivate others to join their spinoff (Rasmussen & Wright, 2015; Rasmussen et al., 2011). Scientists cultivate entrepreneurial competency-oriented skills through industry experience (Knockaert et al., 2011), co-publication and informal knowledge exchange with industrial partners (Link et al., 2007), engagement (Tartari et al., 2014), consulting (D’Este & Perkmann, 2011), and entrepreneurship education (Nabi et al., 2017). Entrepreneurial skills develop iteratively highlighting the importance of prior involvement in patenting (Kolympiris & Klein, 2017), product development (Karlsson & Wigren, 2012), and spinoff establishment (Rasmussen et al., 2011). Conversely, while most entrepreneurs necessarily develop a broad range of knowledge and skills (Lazear, 2004), the relatively narrow focus of scientific training and limited opportunity to work in industry limits the capacity of scientists to pursue entrepreneurial activities (Rasmussen et al., 2011).

Though academic entrepreneurship studies examine skills and experience-related competencies and their relationship to engagement behavior (e.g., Knockaert et al., 2011), liminal competencies uniquely include narratives and skills that enable scientists a priori to construct and develop a robust entrepreneurial identity. In other words, scientists can develop entrepreneurship-related narratives without engaging in entrepreneurial activities, though liminal competencies are required to develop and eventually incorporate an entrepreneurial identity into their self-concept. Conversely, scientists may lack exemplar entrepreneurial narratives and related skills to guide their own rite-of-passage to a commercialization-related identity.

3.3 Social support

While original conceptions of liminality emphasize the supportive role of elders and a communitas, modern conceptions of identity development simultaneously describe the testing and validation of an individual’s emerging “identity narrative” by others whose opinion is valued (Ashforth & Schinoff, 2016; Conroy & O’Leary-Kelly, 2014; Rogers et al., 2017). Thornborrow and Brown (2009) find, for example, that recruits develop their identity as British Paratroopers, an elite military unit, by making social comparisons with peers and mentors to evaluate their progress and affirm their worthiness. Liminars can also derive social support as well as a sense of belonging from peers and colleagues who share the same liminal space (Czarniawska & Mazza, 2003). Conversely, the withholding of social validation by respected audiences can stunt or prevent identity development (Ashforth, 2001; Ashforth et al., 2008; Ibarra, 1999).

Academic entrepreneurship studies frame social support in terms of networks and concomitant resources that enable entrepreneurial success (Rasmussen et al., 2015). In general, the professional networks of scientists are homophilous, that is, comprised primarily of other academic contacts, limiting entrepreneurial outcomes (Hayter, 2016b). Further, following the academic entrepreneurship literature (e.g., Rasmussen et al., 2015), meaningful connections to individuals with industry and entrepreneurship experience may moderate social support from academic contacts and thus enable or constrain entrepreneurial identity development.

Research shows that scientists strongly identify with peer groups at the workplace and base their entrepreneurial intentions on social norms (Obschonka et al., 2012). While peer scientists can motivate entrepreneurial activities, so too can they discourage and penalize entrepreneurial behavior if viewed in conflict with traditional scientific values (Bercovitz & Feldman, 2008; Colyvas, 2007) or as an unnecessary distraction during, for example, the training of postdocs (Hayter & Parker, 2019). Social support (or opposition) for entrepreneurship also manifests at the laboratory, departmental, and institutional level for faculty (Bercovitz & Feldman, 2008; Klingbeil et al., 2019; Rasmussen et al., 2014) and students (Fini et al., 2011; Roach, 2017).

Daunting social barriers also exist for women and under-represented minorities who wish to participate in commercialization-focused activities (Ding et al., 2006; Gurău et al., 2020; Haeussler & Colyvas, 2011). Family and friends can also serve as entrepreneurial role models and provide (or withhold) support important for entrepreneurial identity development, especially among students (Hahn et al., 2019).

Social support is a critical determinant of the extent to which scientists experience the liminal process, especially liminality. As discussed above, liminal individuals experience uncertainty, anxiety, and even excitement. However, absent supportive mentors and colleagues (a “communitas”) or a shared entrepreneurial narrative, liminal scientists must “go it alone,” with potential consequences to their well-being (e.g., Petriglieri, 2011). Further, detrimental impacts experienced during entrepreneurial identity development may only be heightened when social barriers are manifest in institutional sexism and/or rasicm, which may also limit access to resources, policies, and programs (discussed below) that are important to entrepreneurial identity development.

3.4 Organizational, institutional, and ecosystem support

Organizational and institutional factors also have implications for how identities develop. Early studies frame the identity-related role of institutions in terms of socialization, whereby newcomers are transformed from outsiders to functional, engaged, and effective insiders within a specific organizational context (Van Maanen & Schein, 1979). Newcomers are introduced, often through formal means, to appropriate behaviors, cultural norms, and notions of success (Ashforth, 2001; Ashforth & Schinoff, 2016).

Socialization can be strongly institutionalized in environments, such as the military, whereby newcomers undertake initiating activities designed to foster loyalty and a collective identity that reflects shared norms and values (Haynie & Shepherd, 2011; Thornborrow & Brown, 2009). Indicators of successful organizational socialization include conformity to identity-related values, increasing performance outcomes, and the adoption of related workspace artifacts, attire, and lexica (Ashforth, 2001; Trice & Beyer, 1993). As mentioned, socialization is also guided and reinforced through institutionalized narratives that guide what is deemed appropriate behavior by organizations, institutions, and societies (Ibarra & Barbulescu, 2010).

Individuals may experience “over-socialization” whereby emotional space is limited or unavailable for sensemaking and identity play, thus diminishing individual creativity and adaptability (Thornborrow & Brown, 2009). Or individual transitions can be under-institutionalized when target roles remain undefined, leading to insecurity and isolation (Ibarra & Obodaru, 2016; Kahn, 2001). Nonetheless, Ibarra and Obodaru (2016) posit that under-institutionalized environments are best for fostering identity development especially when they encourage identity play in support of organizational objectives.

Academic entrepreneurship scholars describe the emergence of “entrepreneurial universities,” that encourage and support commercialization through robust programs and policies (e.g., Guerrero et al., 2016). Early institutional efforts focused on the establishment of university technology transfer offices (TTOs) to ensure statutory compliance and provide legal, technical, and entrepreneurship support (Bradley et al., 2013). Research universities have also established other types of entrepreneurship programs and policies, such as incubators (Kolympiris & Klein, 2017), seed funds (Croce et al., 2014), and commercialization-oriented criteria for promotion and tenure (Grimaldi et al., 2011). A growing number of entrepreneurship education programs (Bolzani et al., 2021), supplemented by business plan competitions (Hsu et al., 2007), and hackathons (Shah & Pahnke, 2014) offer students and faculty opportunities to develop related skills and experience.

Research interest has more recently highlighted the potential of ecosystem perspectives which frame entrepreneurial development in terms of constituent, multi-level institutional and regional elements, their interconnectivity, and collective ability to provide critical information and resources (e.g., Feldman et al., 2019; Hayter, 2016a; Hayter et al., 2018; Theodoraki et al., 2018). Ecosystem perspectives also emphasize the importance of geography (e.g., Acs et al., 2017) and regional economies (Casper, 2013) on entrepreneurial development, including recent research that ties early industrial evolution to place (Aversa & Jenkins, 2019).

From a liminal process perspective, entrepreneurship education, programs, and policies may provide scientists with discrete opportunities for identity play and reinforce early and ongoing identity work. Further, the emergent ecosystem concepts seem consistent with need for identity multi-level institutions and regions that can support an analogous rite-of-passage for scientists as they undertake the liminal process of developing an entrepreneurial identity. The challenge, however, is doing so in a way that is complementary to existing scientific disciplines and logics (Hsu et al., 2007), given that institutions and ecosystems shape the conditions for entrepreneurial development (Spigel, 2017).

3.5 Temporal factors

A critical, yet understudied component of identity development is the role of time, what the literature terms temporal factors (Beech, 2011). While liminality was traditionally conceptualized as a temporary transition, recent research finds that unemployed individuals may be “permanently liminal” (Johnsen & Sørensen, 2015) or that individuals, such as business consultants (Sturdy et al., 2006) and freelancers (Tempest & Starkey, 2004), choose to live a life where they move from project to project and are thus in continuous social limbo. Moreover, even in cases whereby entrepreneurial identity has been constructed and becomes central, an individuals’ passion towards venturing tends to decrease over time thus affecting the outcome of the liminal process (Collewaert et al., 2016).

While academic entrepreneurship research rarely focuses on temporal factors, studies show that faculty scientists engage in entrepreneurial activities later in their career compared to other types of entrepreneurs (Haeussler & Colyvas, 2011). This may be because junior faculty are encouraged to focus on their scientific contributions and achieve tenure before pursuing commercialization-related activities (Clarysse et al., 2011). However, entrepreneurial engagement may differ by scientific training and background: Roach (2017) finds that PhD students who work in labs that encourage entrepreneurship are more likely interested in an entrepreneurial career and therefore work in a startup following graduation.

From a liminal process perspective, the identity development factors discussed above likely interact reflexively to slow or accelerate identity development. Müller (2010) shows, for example, that long lags prior to entrepreneurial engagement among scientists are attributed to time needed for the acquisition of entrepreneurial skills. Similarly, weak liminal competencies, including lack of entrepreneurial experience, may prolong the time required for a scientist to launch into and complete the liminal process, just as—following Haynie and Shepherd (2011)—prolonged liminality increases the probability of entrepreneurial identity exit among scientists.

Conversely, graduate students and postdocs are generally younger than most faculty and have therefore spent less time developing their scientific identity (or being socialized) potentially making them more amenable to commercialization-focused entrepreneurial identity development, depending on social support, among other factors. Further, scientists who have developed liminal competencies through prior experience developing and enacting other professional identities (e.g., former soldier, accountant, or journalist), are more likely to complete the liminal process compared to those who have not. Finally, institutional programs and policies may not only provide an opportunity for entrepreneurial identity play, but they might also accelerate identity work.

4 Model specification

Figure 1 provides a stylized illustration of the liminal venturing model the purpose of which is to explain why and how a commercialization-focused entrepreneurial identity develops among individuals who already possess a central professional identity as a scientist. It is important to note that while the model includes the five moderating factors discussed above, each may be positively or negatively activated at different times during the liminal process.

As the liminal process begins (a), scientists may conduct autonomous entrepreneurial identity play by, for example, taking an action-based entrepreneurship class or program (Mukesh et al., 2020; Rasmussen & Sørheim, 2006). Alternatively, individuals may experience a controlling event or scenario such as the eventual realization by postdoc scientists that they will not obtain a tenure-track position at a research university (Hayter & Parker, 2019; Hudson et al., 2018). These scenarios may result in outcomes b1 or b2, which are positively or negatively moderated by agency. During identity play, scientists may choose to discontinue the liminal process (b1), resulting in entrepreneurial inaction, or they may decide to autonomously commit to entrepreneurial identity work (b2). Individuals facing controlling circumstances are instead propelled into entrepreneurial identity work (b2) with little choice.

During identity work, scientists may experience uncertainty, anxiety, and potentially excitement associated with liminality. No matter the reason that individuals undertake identity work (i.e., by choice or not), passion provides a proxy for the degree to which an emerging entrepreneurial identity becomes important, if not central, and thus the extent to which individuals enact that identity relative to their existing scientific identity. It is also during identity work that social support becomes relatively more important and—positively or negatively—moderates how scientists experience liminality. For example, experienced entrepreneurial coaches and mentors can help liminal scientists build knowledge and skills that can improve their capabilities as entrepreneurs. Conversely, PIs might penalize postdocs for seeking out entrepreneurship-oriented training because it “distracts” from their scientific responsibilities (Hayter & Parker, 2019). Liminal competence is also critical for navigating identity work; individuals who have experience developing new personal narratives and skills are more likely to navigate liminality better.

As discussed, identity work not only focuses on forming and strengthening a new identity, but it may also simultaneously entail the revision of an existing identity. The liminal venturing model thus includes concurrent revision (d) which influences how an individual enacts their existing scientific identity (Jain et al., 2009). Specifically, an emergent entrepreneurial identity may positively or negatively impact academic responsibilities in areas such as publication productivity, graduate student mentoring, and community engagement (Fini et al., 2021; Jain et al., 2009; Lam, 2011).

The behavioral outcomes of undertaking identity work can vary widely. Scientists may discontinue entrepreneurial identity work (e) due to, for example, criticism from academic colleagues (Grimaldi et al., 2011; Roach, 2017), administrative conflicts (Ambos et al., 2008; Huyghe & Knockaert, 2015; Toole & Czarnitzki, 2010), or family conflicts (Nikunen, 2012). Individuals undertaking identity work due to a controlling event may similarly choose to discontinue their pursuit of non-scientific, non-entrepreneurial professional alternatives (e). In this instance, scientists may choose to singularly enact their primary scientific identity, seek to develop a new (non-entrepreneurial) identity type, and/or decide to exit their central scientific identity altogether, the latter associated with significant negative personal and emotional consequences (Ibarra & Obodaru, 2016; Petriglieri, 2011; Thoits, 1983).

In addition to discontinuing identity work, scientists may also (f) incorporate a new entrepreneurial identity into their self-concept, or their scientific and entrepreneurial identities may simultaneously exist in conflict. Incorporation is exemplified in the literature by Jain and colleagues (2009) who find that tenured faculty reconcile their scientific and commercial identities through hybridization, though they maintain the scientific as central through a process of delegating and buffering. Other instances likely exist whereby academic scientists, including graduate students and postdocs, cannot reconcile identity conflict. Regardless, the degree to which identities coexist harmoniously or are in continual conflict not only affects their behavioral enactment of an entrepreneurial identity (g), but it also impacts physical and emotional well-being of the individual. Regardless, scientists may choose to behaviorally enact their emergent entrepreneurial identity through commercially oriented activities, from a brief engagement in technology licensing or ongoing development partnership with a corporation or startup. These individuals may simultaneously exit their role as a scientist (h) by leaving their academic position to focus on building a new entrepreneurial career.

Of course, the liminal venturing process occurs within organizational and institutional environments, as well as entrepreneurship ecosystems, that impact identity development. A deep body of literature explores programmatic, policy, and regional factors that impact commercialization success (see Hayter et al., 2018 for a recent review) and, though not framed as such, likely influence identity development. Absent from the academic entrepreneurship literature (see Garud et al., 2014 for a notable exception) and critical to our liminal venturing model, however, is the role of shared entrepreneurial narratives. As discussed above, narratives are critical throughout the liminal process given that they guide liminal competence building, social support, and identity-supporting interventions. Narratives also guide other institutional functions, such as through routines, hiring practices, and formal enactment of cultural norms (Kahn, 2001) that are often neglected by scholars, yet significantly influence entrepreneurial culture and behavioral enactment.

Finally, the liminal venturing model influences and is influenced by temporal factors (Garud et al., 2014). Given that entrepreneurial engagement is a prerequisite for commercialization, the time necessary for scientists to engage in identity play, autonomously undertake or be propelled into identity work, and (if applicable) behaviorally enact an entrepreneurial identity is a critical component of commercialization success. For example, relating to early-stage university spinoff performance, all things being equal, the more time required for commercialization, the more likely a spinoff will fail or become a technology lifestyle company (Harrison & Leitch, 2010). Conversely, early-stage policies and programs (such as the U.S. National Science Foundation [NSF] I-Corps program, discussed below) and shared organizational and institutional entrepreneurial narratives may accelerate entrepreneurial identity development thus reducing the time necessary for commercialization. Perhaps just as important, policies and programs might also accelerate a scientist’s realization that they do not wish to develop an entrepreneurial identity.

5 Contributions and implications

This paper introduces liminal venturing, a process model for conceptualizing entrepreneurial identity development among academic scientists. Pioneering empirical works (e.g., Huyghe et al., 2016; Jain et al., 2009) investigate entrepreneurial identity dynamics among scientists, yet scholars have been slow to embrace identity as a critical explanatory factor for academic entrepreneurship (Balven et al., 2018). By integrating concepts from both identity and entrepreneurship, our model provides a stylized explanation of the origins of entrepreneurial identity, factors that influence identity development over time, and the relationship between entrepreneurial identity development and commercialization-focused entrepreneurial behavior. Our theorizing draws on the liminality-as-process literature (Söderlund & Borg, 2018) that explains how a new identity is generated, formed, and eventually integrated into one’s existing self-concept.

Entrepreneurship scholars have long been interested in how entrepreneurs employ cognitive strategies to behaviorally manifest individual motivations and needs (Haynie et al., 2010). According to Haynie and colleagues (2010), metacognition is a critical component of an entrepreneurial mindset, “a growth-oriented perspective through which individuals promote flexibility, creativity, continuous innovation, and renewal…[and] can identify and exploit new opportunities…” (Ireland et al., 2003, p. 968). In the parlance of liminal venturing, an individual who possesses an entrepreneurial mindset is already autonomously motivated and, following Haynie and colleagues (2010), cognitively enabled to undertake commercialization-focused entrepreneurial behavior. Of course, the entrepreneurship literature generally assumes that individuals engaging in entrepreneurial activity are motivated to be (or to become) entrepreneurs, just as academic entrepreneurship studies examine motivations among academic entrepreneurs after they have engaged in entrepreneurial activities.

What the literature does not provide are conceptual tools to understand why and how an entrepreneurial identity develops, as well as how identity dynamics influence firm-level performance, much less explain institutional and ecosystem impact. Liminal venturing helps fill this conspicuous theoretical gap by introducing a process model to explain not only the origins of an entrepreneurial identity, but also factors that influence its development and possible incorporation into one’s self-concept. As such, the paper addresses recent suggestions to focus on identity-based micro-processes that might provide insights into commercialization behavior among scientists (Balven et al., 2018).

To advance our understanding of identity development among academic scientists, and potentially other strong professional identities, empirical testing and refinement of the liminal venturing model is required. Specifically, elements of our model should be deconstructed to reflect micro-level theory related to identity development. Absent from both the identity and entrepreneurship literatures, for example, is research related to why and how scientists develop intrinsic interest in entrepreneurship as well as how intrinsically-motivated scientists experiment with provisional entrepreneurial selves. While intrinsic motivations and identity play are proposed as antecedents to identity work, future research might—in addition to testing these assumptions—illuminate the evolution and interdependencies between the two. Scholars might also explore how transition into identity work through extrinsically motivated, controlling circumstances impacts the extent to which scientists, especially graduate students and postdocs, are able to develop and incorporate a new entrepreneurial identity or if, instead, the they are more likely to exit the liminal process.

Another intriguing line of research focuses on further studying and refining the relationship among passion, motivations, and identity development. As discussed, research on entrepreneurial passion generally assumes that passion and behavior are functions of identity centrality, though differences exist regarding their sequencing. A recent study highlights the relationship between autonomy and compulsion in the development of entrepreneurial passion (Murnieks et al., 2020a, b). Given the proposed role of autonomous motivations in triggering identity development, future research might examine how harmonious entrepreneurial passions similarly develop during identity play as well as their interaction with entrepreneurial motivations (Murnieks et al. 2020b; Murnieks et al., 2020a, b). Similarly, how do entrepreneurial passions develop not only among individuals who are non-entrepreneurs, but also how these relate to existing passions associated with their central identity?

Systematic and longitudinal investigation of entrepreneurial identity development among scientists will also yield insights into the micro–macro emergence, composition, and evolution of entrepreneurial narratives. According to Garud and colleagues (2014), entrepreneurial actors and contexts are co-created as “entrepreneurs contextualize innovation through their relational, temporal and performative efforts” (p. 1178). Though the authors do not discuss identity, narratives are defined in the identity literature as stories constructed by individuals to provide meaning, or they are viewed as culturally-legitimized accounts that guide what is deemed appropriate behavior by organizations or societies (Ibarra & Barbulescu, 2010; Ibarra & Obodaru, 2016). While liminal venturing introduces identity development as a critical component for entrepreneurship ecosystems, future scholarship can investigate how individuals develop entrepreneurial narratives and the extent to which those narratives impact local ecosystems, among other contextual elements.

Mirroring the identity literature, temporal aspects of identity development seem to hold enormous potential for application to academic entrepreneurship. In general, little is known about the time it takes to commercialize university technologies, and even less regarding the time-related aspects of entrepreneurial identity development among scientists. Understanding the extent to which identity development is an iterative and cyclical process can offer guidance on refining support structures designed to foster technology transfer from academia to markets.

Scholars might also investigate the extent to which research universities and specific programs, policies, and other interventions promote or constrain identity development, including how impact may differ by gender, race, and other personal characteristics. The NSF Innovation Corps (I-Corps)Footnote 1 program is illustrative. I-Corps was established in 2011 to improve commercialization outcomes associated with the NSF’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grant programFootnote 2 by attempting to ensure that academic scientists “…[D]on’t build things that people don’t care about and/or aren’t accepted in the marketplace” (Arkilic, 2019, p. 73). Administered at the university and national level, I-Corps provides scientists with a mentored process of customer discovery,Footnote 3 a methodology for interviewing dozens of potential customers to understand their specific needs and inform a venture’s value proposition. While program impact has yet to be systematically evaluated, Arkilic (2019) describes I-Corps as a vehicle for scientists to “explore the unknown” (p. 80), while learning other aspects of commercialization. Outcomes among scientists range from subsequent spinoff establishment and receipt of equity financing, to dropping out of the program (Arkilic, 2019; Bozeman & Youtie, 2017).

Liminal venturing provides scholars with a framework to examine the impact of I-Corps based on the extent to which it provides structured identity play and empowers individuals to adopt and further develop an entrepreneurial identity. Further, programs like I-Corps operate within institutional and regional ecosystems generally comprised of constellations of actors, networks, and environments the confluence of which enable or constrain entrepreneurial identity development at the meso and macro levels. These multi-level interactions no-doubt hold promise for future investigation.

In conclusion, liminal venturing offers a novel approach to conceptualize entrepreneurial development among scientists emphasizing the extent to which their actions lead to commercialization-related outcomes. By dedicating attention not only to identity related enablers and constraints at the individual level but also moderating contextual and temporal factors, liminal venturing provides a more holistic perspective on why and how entrepreneurial identities develop—or do not. Considering the importance of academic entrepreneurs for the commercialization of university research, we are confident that the liminal venturing framework will offer scholars a nuanced framework to understand and evaluate the broader impact not only of research universities, but also public investments in scientific research writ large (Fini et al., 2018). From this starting point, we also hope that future scholarship will refine liminal venturing and examine its utility for explaining entrepreneurial identity development within the context of other non-entrepreneurial professional “callings,” such as musicians, artists, coders, and chefs, while theorizing further its role in academic entrepreneurship.

Notes

See https://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/i-corps/about.jsp (Accessed March 1, 2021).

The NSF SBIR program provides startups and small businesses with up to $1.75 million in non-equity funding to develop early-stage technologies. For more information, see https://seedfund.nsf.gov/about/ (Accessed March 1, 2020).

References

Acs, Z. J., Stam, E., Audretsch, D. B., & O’Connor, A. (2017). The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9864-8

Ambos, T. C., Mäkelä, K., Birkinshaw, J., & D’Este, P. (2008). When does university research get commercialized? Creating ambidexterity in research institutions. Journal of Management Studies, 45(8), 1424–1447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00804.x

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray, S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00068-4

Arkilic, E. (2019). Raising the NSF Innovation Corps. In M. Wisnioski, E. Hintz, & M. Kleine (Eds.), Does America Need More Innovators? (pp. 69–82). The MIT Press.

Ashforth, B. E. (2001). Role Transitions in Organizational Life: An Identity-Based Perspective. Erlbaum.

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34(3), 325–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316059

Ashforth, B. E., & Schinoff, B. S. (2016). Identity under Construction: How Individuals Come to Define Themselves in Organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3, 111–137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062322

Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a Day’s Work: Boundaries and Micro Role Transitions. The Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472–491. https://doi.org/10.2307/259305

Aversa, P., & Jenkins, M. (2019). The primordial soup of cluster genesis: A historical case study of the British Motorsport Valley. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2019(1), 16510. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2019.16510

Balven, R., Fenters, V., Siegel, D. S., & Waldman, D. (2018). Academic entrepreneurship: The roles of identity, motivation, championing, education, work-life balance, and organizational justice. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2016.0127

Beech, N. (2011). Liminality and the practices of identity reconstruction. Human Relations, 64(2), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710371235

Bercovitz, J., & Feldman, M. (2008). Academic entrepreneurs: Organizational change at the individual level. Organization Science, 19(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0295

Blank, S. (2013). The Four Steps to the Epiphany: Succesful strategies for products that win. K&S Ranch.

Boland, T., & Griffin, R. (2015). The death of unemployment and the birth of job-seeking in welfare policy: Governing a liminal experience. Irish Journal of Sociology, 23(2), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.7227/IJS.23.2.3

Bolzani, D., Munari, F., Rasmussen, E., & Toschi, L. (2021). Technology transfer offices as providers of science and technology entrepreneurship education. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(2), 335–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-020-09788-4

Bozeman, B., & Youtie, J. (2017). Socio-economic impacts and public value of government-funded research: Lessons from four US National Science Foundation initiatives. Research Policy, 46(8), 1387–1398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.06.003

Bradley, S. R., Hayter, C. S., & Link, A. N. (2013). Models and methods of university technology transfer. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 9(6), 571–650. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000048

Callander, A., & Cummings, M. E. (2021). Liminal spaces: A review of the art in entrepreneurship and the entrepreneurship in art. Small Business Economics, 57(2), 739–754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00421-0

Casper, S. (2013). The spill-over theory reversed: The impact of regional economies on the commercialization of university science. Research Policy, 42(8), 1313–1324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.04.005.

Clarysse, B., Tartari, V., & Salter, A. (2011). The impact of entrepreneurial capacity, experience and organizational support on academic entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 40(8), 1084–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.05.010

Collewaert, V., Anseel, F., Crommelinck, M., De Beuckelaer, A., & Vermeire, J. (2016). When Passion Fades: Disentangling the Temporal Dynamics of Entrepreneurial Passion for Founding. Journal of Management Studies, 53(6), 966–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12193

Colyvas, J. A. (2007). From divergent meanings to common practices: The early institutionalization of technology transfer in the life sciences at Stanford University. Research Policy, 36(4), 456–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.02.019

Conroy, S. A., & O’Leary-Kelly, A. M. (2014). Letting go and moving on: Work-related identity loss and recovery. Academy of Management Review, 39(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0396

Croce, A., Grilli, L., & Murtinu, S. (2014). Venture capital enters academia: An analysis of university-managed funds. Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(5), 688–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-013-9317-8

Czarniawska, B., & Mazza, C. (2003). Consulting as a liminal space. Human Relations, 56(3), 267–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726703056003612

D’Este, P., & Perkmann, M. (2011). Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations. Journal of Technology Transfer, 36(3), 316–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-010-9153-z

Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-Determination Theory in Work Organizations: The State of a Science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108

Ding, W. W., Murray, F., & Stuart, T. E. (2006). Gender Differences in Patenting in the Academic Life Sciences. Science, 313(5787), 665 LP – 667. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1124832

Dutton, J. E., Roberts, L. M., & Bednar, J. (2010). Pathways for positive identity construction at work: Four types of positive identity and the building of social resources. Academy of Management Review, 35(2), 265–293. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2010.48463334

Ebaugh, H. (1988). Becoming an Ex: The Process of Role Exit. The University of Chicago Press.

Farmer, S. M., Yao, X., & Kung-Mcintyre, K. (2011). The Behavioral Impact of Entrepreneur Identity Aspiration and Prior Entrepreneurial Experience. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 35(2), 245–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00358.x

Fauchart, E., & Gruber, M. (2011). Darwinians, communitarians, and missionaries: The role of founder identity in entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 935–957. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0211

Faulkner, R. R. (1973). Career Concerns and Mobility Motivations of Orchestra Musicians. Sociological Quarterly, 14(3), 334–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1973.tb00864.x

Feldman, M., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2019). New developments in innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Industrial and Corporate Change, 28(4), 817–826. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtz031

Fini, R., Perkmann, M., & Ross, J. (2021). Attention to exploration: The effect of academic entrepreneurship on the production of scientific knowledge. Organization Science, Forthcomin.

Fini, R., Rasmussen, E., Siegel, D., & Wiklund, J. (2018). Rethinking the commercialization of public science: From entrepreneurial outcomes to societal impacts. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0206

Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., Santoni, S., & Sobrero, M. (2011). Complements or substitutes? the role of universities and local context in supporting the creation of academic spin-offs. Research Policy, 40(8), 1113–1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.05.013

Fraher, A. L., & Gabriel, Y. (2014). Dreaming of flying when grounded: Occupational identity and occupational fantasies of furloughed airline pilots. Journal of Management Studies, 51(6), 926–951. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12081

Garud, R., Gehman, J., & Giuliani, A. P. (2014). Contextualizing entrepreneurial innovation: A narrative perspective. Research Policy, 43(7), 1177–1188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.04.015

Grandi, A., & Grimaldi, R. (2005). Academics’ organizational characteristics and the generation of successful business ideas. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(6), 821–845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.07.002

Grimaldi, R., Kenney, M., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2011). 30 years after Bayh-Dole: Reassessing academic entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 40(8), 1045–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.04.005

Guerrero, M., Urbano, D., Fayolle, A., Klofsten, M., & Mian, S. (2016). Entrepreneurial universities: Emerging models in the new social and economic landscape. Small Business Economics, 47(3), 551–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9755-4

Gurău, C., Dana, L.-P., & Light, I. (2020). Overcoming the Liability of Foreignness: A Typology and Model of Immigrant Entrepreneurs. European Management Review, 17(3), 701–717. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12392.

Haeussler, C., & Colyvas, J. A. (2011). Breaking the Ivory Tower: Academic entrepreneurship in the life sciences in UK and Germany. Research Policy, 40(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.09.012

Hahn, D., Minola, T., & Eddleston, K. A. (2019). How do Scientists Contribute to the Performance of Innovative Start-ups? An Imprinting Perspective on Open Innovation. Journal of Management Studies, 56(5), 895–928. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12418

Harrison, R. T., & Leitch, C. (2010). Voodoo Institution or Entrepreneurial University? Spin-off Companies, the Entrepreneurial System and Regional Development in the UK. Regional Studies, 44(9), 1241–1262. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903167912

Haynie, J. M., & Shepherd, D. (2011). Toward a theory of discontinuous career transition: Investigating career transitions necessitated by traumatic life events. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 501–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021450

Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D., Mosakowski, E., & Earley, P. C. (2010). A situated metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.10.001

Hayter, C. (2011). In search of the profit-maximizing actor: Motivations and definitions of success from nascent academic entrepreneurs. Journal of Technology Transfer, 36(3), 340–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-010-9196-1

Hayter, C. (2016a). A trajectory of early-stage spinoff success: The role of knowledge intermediaries within an entrepreneurial university ecosystem. Small Business Economics, 47(3), 633–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9756-3

Hayter, C. (2016b). Constraining entrepreneurial development: A knowledge-based view of social networks among academic entrepreneurs. Research Policy, 45(2), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.11.003

Hayter, C. S., Nelson, A. J., Zayed, S., & O’Connor, A. C. (2018). Conceptualizing academic entrepreneurship ecosystems: a review, analysis and extension of the literature. Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(4), 1039–1082. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9657-5.

Hayter, C. S., & Parker, M. A. (2019). Factors that influence the transition of university postdocs to non-academic scientific careers: An exploratory study. Research Policy, 48(3), 556–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.09.009

Hmieleski, K. M., & Powell, E. E. (2018). The psychological foundations of university science commercialization: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(1), 43–77. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2016.0139

Hoang, H., & Gimeno, J. (2010). Becoming a founder: How founder role identity affects entrepreneurial transitions and persistence in founding. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.07.002

Hood, J. N., & Young, J. E. (1993). Entrepreneurship’s requisite areas of development: A survey of top executives in successful entrepreneurial firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(2), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(93)90015-W

Hsu, D. H., Roberts, E. B., & Eesley, C. E. (2007). Entrepreneurs from technology-based universities: Evidence from MIT. Research Policy, 36(5), 768–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.03.001

Hudson, T. D., Haley, K. J., Jaeger, A. J., Mitchall, A., Dinin, A., & Dunstan, S. B. (2018). Becoming a legitimate scientist: Science identity of postdocs in STEM fields. Review of Higher Education, 41(4), 607–639. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2018.0027

Huyghe, A., & Knockaert, M. (2015). The influence of organizational culture and climate on entrepreneurial intentions among research scientists. Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(1), 138–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-014-9333-3

Huyghe, A., Knockaert, M., & Obschonka, M. (2016). Unraveling the “passion orchestra” in academia. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(3), 344–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.03.002

Ibarra, H. (1999). Provisional selves: Experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 764–791. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667055

Ibarra, H., & Barbulescu, R. (2010). Identity as narrative: Prevalence, effectiveness, and consequences of narrative identity work in Macro work role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 35(1), 135–154. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2010.45577925

Ibarra, H., & Obodaru, O. (2016). Betwixt and between identities: Liminal experience in contemporary careers. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36, 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.11.003

Ibarra, H., & Petriglieri, J. L. (2010). Identity work and play. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 23(1), 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811011017180

Ireland, R. D., Hitt, M. A., & Sirmon, D. G. (2003). A Model of Strategic Entrepreneurship: The Construct and its Dimensions. Journal of Management, 29(6), 963–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(03)00086-2

Jain, S., George, G., & Maltarich, M. (2009). Academics or entrepreneurs? Investigating role identity modification of university scientists involved in commercialization activity. Research Policy, 38(6), 922–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.02.007

Johnsen, C. G., & Sørensen, B. M. (2015). ‘It’s capitalism on coke!’: From temporary to permanent liminality in organization studies. Culture and Organization, 21(4), 321–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2014.901326

Kahn, W. A. (2001). Holding Environments at Work. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 37(3), 260–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886301373001

Karlsson, T., & Wigren, C. (2012). Start-ups among university employees: The influence of legitimacy, human capital and social capital. Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(3), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-010-9175-6

Kenney, M., & Patton, D. (2011). Does inventor ownership encourage university research-derived entrepreneurship? A Six University Comparison. Research Policy, 40(8), 1100–1112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.05.012

Kira, M., & Balkin, D. B. (2014). Interactions between work and identities: Thriving, withering, or redefining the self? Human Resource Management Review, 24(2), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.10.001

Klingbeil, C., Semrau, T., Ebers, M., & Wilhelm, H. (2019). Logics, Leaders, Lab Coats: A Multi-Level Study on How Institutional Logics are Linked to Entrepreneurial Intentions in Academia. Journal of Management Studies, 56(5), 929–965. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12416

Knockaert, M., Ucbasaran, D., Wright, M., & Clarysse, B. (2011). The relationship between knowledge transfer, top management team composition, and performance: The case of science-based entrepreneurial firms. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 35(4), 777–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00405.x

Kolympiris, C., & Klein, P. G. (2017). The Effects of Academic Incubators on University Innovation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 11(2), 145–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1242

Ladge, J. J., Clair, J. A., & Greenberg, D. (2012). Cross-domain identity transition during liminal periods: Constructing multiple selves as professional and mother during pregnancy. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1449–1471. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0538

Lam, A. (2011). What motivates academic scientists to engage in research commercialization: “Gold”, “ribbon” or “puzzle”? Research Policy, 40(10), 1354–1368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.09.002

Lazear, E. P. (2004). Balanced skills and entrepreneurship. American Economic Review, 94(2), 208–211. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828041301425

Link, A. N., Siegel, D. S., & Bozeman, B. (2007). An empirical analysis of the propensity of academics to engage in informal university technology transfer. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(4), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtm020

Lockett, A., & Wright, M. (2005). Resources, capabilities, risk capital and the creation of university spin-out companies. Research Policy, 34(7), 1043–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.05.006

Meek, W. R., & Wood, M. S. (2016). Navigating a Sea of Change: Identity Misalignment and Adaptation in Academic Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(5), 1093–1120. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12163

Mukesh, H. V., Pillai, K. R., & Mamman, J. (2020). Action-embedded pedagogy in entrepreneurship education: An experimental enquiry. Studies in Higher Education, 45(8), 1679–1693. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1599848

Müller, K. (2010). Academic spin-off’s transfer speed-Analyzing the time from leaving university to venture. Research Policy, 39(2), 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.12.001

Murnieks, C. Y., Klotz, A. C., & Shepherd, D. A. (2020a). Entrepreneurial motivation: A review of the literature and an agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(2), 115–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2374

Murnieks, C. Y., Mosakowski, E., & Cardon, M. S. (2014). Pathways of Passion: Identity Centrality, Passion, and Behavior Among Entrepreneurs. Journal of Management, 40(6), 1583–1606. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311433855

Murnieks, Charles Y, Cardon, M. S., & Haynie, J. M. (2020). Fueling the fire: Examining identity centrality, affective interpersonal commitment and gender as drivers of entrepreneurial passion. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(1), 105909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.10.007

Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 16(2), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0026

Nikunen, M. (2012). Changing university work, freedom, flexibility and family. Studies in Higher Education, 37(6), 713–729. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.542453

O’Kane, C., Mangematin, V., Zhang, J. A., & Cunningham, J. A. (2020). How university-based principal investigators shape a hybrid role identity. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120179

Obschonka, M., Goethner, M., Silbereisen, R. K., & Cantner, U. (2012). Social identity and the transition to entrepreneurship: The role of group identification with workplace peers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.007

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business Model Generation: a Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Petriglieri, J. L. (2011). Under threat: Responses to and the consequences of threats to individuals’ identities. Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 641–662. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0087

Prashantham, S., & Floyd, S. W. (2019). Navigating liminality in new venture internationalization. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(3), 513–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.01.001

Pratt, M. G., Rockmann, K. W., & Kaufmann, J. B. (2006). Constructing professional identity: The role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 235–262. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.20786060

Rasmussen, E. A., & Sørheim, R. (2006). Action-based entrepreneurship education. Technovation, 26(2), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2005.06.012

Rasmussen, E., Mosey, S., & Wright, M. (2011). The Evolution of Entrepreneurial Competencies: A Longitudinal Study of University Spin-Off Venture Emergence. Journal of Management Studies, 48(6), 1314–1345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00995.x

Rasmussen, E., Mosey, S., & Wright, M. (2014). The influence of university departments on the evolution of entrepreneurial competencies in spin-off ventures. Research Policy, 43(1), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.06.007