Abstract

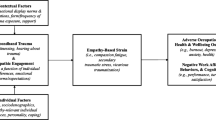

Theorizing a sociology of emotion that links micro-level resources to macro-level forces, this article extends previous work on emotional capital in relation to emotional experiences and management. Emerging from Bourdieu’s theory of social practice, emotional capital is a form of cultural capital that includes the emotion-specific, trans-situational resources that individuals activate and embody in distinct fields. Contrary to prior conceptualizations, I argue that emotional capital is neither wholly gender-neutral nor exclusively feminine. Men may lay claim to emotional capital as a valued resource within particular fields. The concept of emotional capital should be seen as distinct from emotion management and felt emotional experience and distinctions between primary and secondary sources of capital clarify the simultaneously durable and evolving nature of capital and the habitus. To illustrate these conceptual refinements, I use interview and diary data from male nurses. Men bring primary emotional capital, developed during primary socialization, to the nursing profession while also developing secondary capital through occupational socialization centered on empathy and compassion. The construct of emotional capital is refined as a structured yet dynamic resource developed through primary and secondary socialization and activated and embodied in everyday emotion practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Under-theorized but increasingly utilized in the sociology of emotion, education, and occupations, the concept of emotional capital holds promise for furthering emotion scholarship by linking individual resources and processes to macro-structural forces, including “social order, social inequality, and social cohesion” (Thoits 2004, p. 372). While the utility of Bourdieu’s conception of social and cultural capital is “beyond dispute” (Lareau and Weininger 2003, p. 568), current research has increasingly conceptualized emotion, too, as a type of embodied cultural capital that shapes the development of “caring selves” (Stacey 2011), self-processes of “emotional mining” (Schweingruber and Berns 2005), and the reproduction of class inequality (Reay 2004).

Emotional capital is a tripartite concept composed of emotion-based knowledge, management skills, and capacities to feel that links self-processes and resources to group membership and social location. In contrast to other conceptions of emotion-based resources such as “emotional intelligence” (Goleman 1995; Salovey and Mayer 1990) and “emotional competencies” (Gendron 2004), emotional capital posits a direct relationship between macro-structures and micro-resources. Like economic capital, emotional capital is unequally distributed in society and is distinct from practice—in this case, the situated activation and embodiment of emotional experience, expression, and management (Hochschild 1979; Shott 1979). Within this framework, emotion is reflective of “the interests of individuals within everyday interaction while, at the same time, (re) producing the broader structural and cultural conditions in which such interactions occur” (Erickson and Stacey 2013, p. 179). As a trans-situational resource, emotional capital is inextricably linked to variations in power and privilege in contemporary society, making it a key concept for addressing the role of emotion in classic sociological concerns.

This article examines emotional capital directly. The first section reviews Bourdieu’s theory of social practice and situates emotional capital within this framework as a form of embodied cultural capital. In the second section, I trace the concept’s development in the literature to highlight three conceptual gaps related to (1) gender, (2) emotion practice, and (3) socialization. Finally, I offer a revised conceptualization of emotional capital using case study data from men in nursing. Emotional capital emerges as a gendered, simultaneously rigid and dynamic resource that individuals possess and use as they engage in emotion practice. The accumulation, embodiment, and activation of emotional capital are theorized as part of an individual’s habitus—the product and productive force of social relations—including the maintenance of privilege through exercises of power.

Bourdieu’s theory of social practice

Poststructuralist at its core, Bourdieu’s (Bourdieu 1986, 1990) theoretical work seeks to transcend (1) the dualism between structural determinism and humanistic voluntarism, (2) the modern view of the consciously-calculating individual, and (3) the objective/subjective divide. Bourdieu “roots human consciousness in practical social life” (Swartz 1997, p. 39) by attending to the non-conscious, pre-reflexive practice of everyday living. Critical to his theory is the concept of habitus: “systems of durable, transposable dispositions” that include “structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures” (Bourdieu 1990, p. 53). Straddling mind/body and conscious/non-conscious dualisms, habitus operates at the visceral level of everyday being and doing rather than as a reflected upon, cohesive set of known beliefs and values held by Enlightenment’s idealized rational actor. Operating in tandem with habitus, capital consists of “attributes, possessions, or qualities of a person or a position exchangeable for goods, services, or esteem” (DiMaggio 1979, p. 1463). In bringing one’s habitus—one’s “embodied schemes” (Bourdieu 1996, p. 467) and “durable dispositions” (Bourdieu 1990, p. 62)—to bear on situated practical needs, individuals draw upon transferable resources, including economic, social, and cultural capital. Social conditions shape these forms of capital, with dominant forms operating as those with the greatest social value (Bourdieu 1986).

Bourdieu’s theory has been criticized as circular and deterministic (Jenkins 1982; King 2000; Swartz 1997) as well as insufficiently attentive to inequalities beyond class, such as gender (Adkins 2004; Skeggs 2004) and race (Emirbayer and Desmond 2012). While his grand theory is beyond the scope of the current analysis, critiques of the Bourdieuian actor as overly-determined highlight the utility of clarifying capital’s dynamic yet fixed nature—clarity, I argue, offered in distinguishing between capital gained in primary socialization versus capital acquired through secondary socialization sources such as occupations. An individual’s habitus is “a generative schema in which social structures come, through the process of socialization, to be embodied as schemes of perception that enable a practical mastery of the world” (Nash 2003, p. 47). Socialization sources include family and education as well as sources that span the length of the life course to shape attitudes, behavior, and emotion (Ryder 1965; Singh-Manoux and Marmot 2005).

Although Bourdieu’s work has been critical to the development of emotional capital, I also synthesize this work with emotion management theory. Emotion management refers to the active effort of individuals and groups to align felt and expressed emotions with interactional emotion norms (or feeling rules)—the constructed and situation-specific expectations for what and how to feel (Hochschild 1979, 1983). These rules vary by gender (Brown 2005; Chaplin et al. 2005; Garside and Klimes-Dougan 2002) as well as occupational setting (Pierce 1995; Wingfield 2010). While emotion management theory has successfully redefined emotion as inherently social (McCarthy 1989; Shott 1979), its fixed attention to the interactional level has limited our understanding of emotion’s scope and the potency with which emotion reciprocally shapes and is shaped by social life. Emotion is more than its conscious management and Hochschild’s approach has, in contrast to Bourdieu, been critiqued as overly agentic and rational (Theodosius 2006). Using emotional capital to understand the emotional resources that individuals hold and how they activate and experience emotion in practice can shed light on the embodied and nonconscious aspects of emotion within social hierarchies of power and distinction (Erickson and Stacey 2013; Scheer 2012). By synthesizing notions of social practice with emotion management theory, a framework of emotion-as-practice combines the determined Bourdieuian social actor with Hochschild’s overly rational emotion manager. The result is a broad conception of emotion as embodied and felt, while also managed and strategically used in interactions contextualized by distinct fields.

Emotional capital: definitions and development

Nowotny (1981) is commonly cited for coining the term “emotional capital” (Gillies 2006; Reay 2004). However, its usage goes back further to Jackson’s (1959) examination of grief. Religion, he argues, enables the individual to “meet the fact of death at the physical level with a firm sense of reality, a healthful expression of feelings, and a capacity to reinvest emotional capital where it will produce the best fruits in life” (1959 p. 219, italics added). The phrase, “capacity to reinvest” hints at the tension between structure and agency that underlies social theory more generally (Archer 1990; Fuchs 2001). Capacities precede an individual’s active role or “reinvestment,” while reflexive agency in shaping emotional capital can, ideally, lead to the “best fruits in life.”

Nowotny’s (1981) work on Austrian women in public life was the first to theorize emotional capital using Bourdieu. She defines emotional capital as “knowledge, contacts, and relations as well as access to emotionally valued skills and assets” (p. 148). Froyum (2010) extends this definition to see emotional capital as an interpersonal resource that “treats emotions and their management as skills or habits that translate into social advantages” (p. 39). Knowledge of situationally appropriate emotional experiences and expressions complements the skills needed to manage emotions. Adding to this definition further, Thoits (2004) argues that emotional capital encompasses not only emotion-based knowledge and skills, but also the capacity to experience “social emotions” predicated on role-taking (Mead 1934; Shott 1979). Combining these definitions, I use emotional capital to refer to one’s trans-situational, emotion-based knowledge, emotion management skills, and feeling capacities, which are both socially emergent and critical to the maintenance of power.Footnote 1 Among the types Bourdieu theorized, emotional capital is a form of embodied cultural capital that emerges from the cultural socialization of the “mindful body” (Scheper-Hughes and Lock 1987)—where “bodily capacities and cultural requirements meet” (Scheer 2012, p. 202).

While Nowotny provided an initial definition of emotional capital, her work did not engage with the sociology of emotion—research being developed contemporaneously by Hochschild (1979, 1983) and others. Similar to Bourdieu’s “sharp separation between masculine society and feminine society” in France (2004, p. 580), Nowotny contextualizes emotional capital within contemporary divisions between public and private spheres. For her, women’s role in the family supplies them with more emotional capital than men. Following this logic, emotional capital has been developed and applied primarily to studies of education and family (Colley 2006; Gillies 2006; Nixon 2011; O’Brien 2008; Reay 2000, 2004; Reid 2009; Zemblyas 2007), though research in the sociology of occupations has begun to use the concept (Cahill 1999; Schweingruber and Berns 2005), particularly in healthcare (Erickson and Stacey 2013; Husso and Hirvonen 2012; Stacey 2011; Virkki 2007). Below I outline three conceptual limitations in this prior work on emotional capital: (1) the concept has been inconsistently linked to gender, (2) its use often conflates capital with practice, and (3) it has been inconsistently theorized as static or dynamic over time.

Emotional capital as feminine or gender-neutral

Prior research largely frames emotional capital as a distinctly feminine resource. Education scholars have critically developed the concept in relation to gender and inequality, however their treatment often fails to examine the full scope of gender’s influence on emotion-based resources. Following Nowotny (1981), Reay (2000, 2004) traces emotional capital across relationships between mothers and children as each navigate class constraints and opportunities within the educational system. She finds that just as wealthier, middle-class families are able to pass along economic resources to their children, middle-class mothers are better positioned to equip their children with emotional resources. Reay theorizes emotional capital as equivalent with mothers’ overall emotional support of their children, obfuscating the relationships among gender, capital, and practice (see Manion 2007; Zemblyas 2007 for a similar critique).Footnote 2

Gillies’ (2006) work on mothers’ support for their school-aged children details the ways in which class shapes the links among emotional capital, self-esteem, protection, and economic success. Explaining her choice to focus on mothers rather than fathers, Gillies argues that fathers took an emotionally detached approach to their child’s schooling because they were unable to manage (control) their feelings of anger. This, she argues, suggests that it is primarily the mother’s emotional capital in service of educational goals that is transferred to the child. Unfortunately, this presumes that men, fathers specifically, have less emotional capital to transfer to children rather than seeing this emotional capital as taking on different forms based on a father’s gendered location and the different emotion norms to which men and women are held. She overly feminizes emotional capital in a manner that precludes theoretical and empirical attention to how it may be shaped by masculinity and mobilized and embodied in men’s everyday lives. Furthermore, a focus on mothers’ transfer of emotional capital to children overlooks the foundational translation of emotional capital into emotion practice, as well as its transformation into other forms of capital. Men in nursing can provide an illustrative case of the relationship between masculinity and emotional capital and men’s activation and embodiment of capital in practice.

In contrast to education scholars, occupational scholars have theorized emotional capital as largely gender neutral. Cahill (1999) and Schweingruber and Berns (2005) examine the role of occupational socialization in shaping emotional capital. Cahill’s study of mortuary students emphasizes student’s prior experiences with death and mortuary work. Schweingruber and Berns’s research on how a sales company trains workers to develop emotional capital for the job connects self-constructions with emotion management. The role of gender or other social statuses in the development of capital is absent from these approaches, suggesting a more gender-neutral conception of emotional capital.

One exception to the absence of gender in occupational work is Virkki’s (2007) study of female social workers and nurses in Finland. Virkki frames emotional capital as a resource exclusive to women: “emotional capital may be a dead letter in the masculine, working-class sphere, where physical superiority is more valued than emotional skills and caring” (p. 278). While this may be the case, the implication that men do not possess any emotional resources is overly essentialist and dilutes the concept’s theoretical possibilities (Manion 2007; Zemblyas 2007).

Conflating emotional capital with practice

Parallel to seeing emotional capital as exclusively feminine or gender-neutral, prior research on the concept often conflates emotional capital with emotional support and well-being—failing to distinguish emotional capital clearly as a resource from its activation in practice. Scholars have operationalized emotional capital as the act of maternal investment women make in the education of their children (Gillies 2006; Reay 2000, 2004). This work equates the intense emotions women reflect in interviews surrounding their child’s education with emotional capital. For example, Gillies (2006) defines emotional capital itself as “emotional investments made by parents as part of their desire to promote their children’s wellbeing and prospects” (p. 285). Such a conceptualization reduces capital to markers of a mother’s concern for her child. Certainly a mother’s concern is an important aspect of socialization, but measuring emotional capital through concern alone is inconsistent with prior definitions (Froyum 2010; Thoits 2004) and limits the focus to rationally articulated emotions. Without clarity about how parents impart knowledge of emotion norms, skills, or experiential capacities to their children, the links among a parent’s emotional capital, the mobilization of that capital, and children’s accumulation of capital remain obscure. Such distinctions are critical to theorizing emotional capital as a resource that is distinct from its use in practice.

In applying the concept, Reay (2004) also conflates emotional capital with emotional experiences: “it was primarily working-class women, with negative personal experiences of schooling, who found it extremely hard to generate resources of emotional capital for their child to draw on if they [were] experiencing difficulties in school” (p. 63). Reay points to the negative emotions of humiliation, embarrassment, and anger that mothers feel as a result of their own educational failure to indicate limited emotional capital. Disagreeing with this characterization of working-class women, Manion (2007) argues that “conditions of poverty may catalyze the development and transfer of specific emotional capital resources” (p. 94). The experiences of the working-class and the poor may actually foster greater emotional capital needed to confront economic adversities. Such claims are difficult to assess when emotional capital is measured only through its practice in the form of proxies such as emotional concern or negative emotions.

Emotional capital as a fixed but malleable resource

A third theme in the literature on emotional capital is the tension between how rigidly capital as well as habitus is “anchored” by social forces during primary socialization (Manion 2007, p. 91) and its sensitivity to modification (Schweingruber and Berns 2005; Stacey 2011). Cahill (1999) examines the emotional capital that mortuary students gained in early family experiences as critical to explaining their occupational success. Students who remained in the mortuary program noted that they were raised around death and that it did not appear to bother them—did not lead to the same emotional experiences and management strategies—as compared to students who lacked this upbringing and ultimately dropped out of the program. In this case, emotional capital gained in primary socialization appears difficult to develop through occupational training. Those without the primary capital gained through early experiences with death were ultimately unable to develop emotional capital later on and, as a result, chose not to perform mortuary work.

By contrast, Schweingruber and Berns (2005) examine how emotional capital is successfully developed on the job through the training of book salespersons. Notably, they find that occupational training emphasizes “emotional mining” and “emotional bridging,” processes through which trainees produce and use their emotional capital for the purpose of selling books. These processes allow salespersons to develop the capital needed to be successful on the job. The question remains: how is it that Cahill’s (1999) mortuary dropouts were unable to produce, and in his view would never be able to develop, the emotional capital that second-generation mortuary students easily embodied while Schweingruber and Berns found that trainees’ dynamically construct new forms of emotional capital? Can emotional capital be developed later in life or is it fixed to one’s primary upbringing? Although Bourdieu’s theory attempts to interrelate “statics and dynamics, structure and process, and stability and change” (Emirbayer and Goldberg 2005, p. 504), the implications for theorizing emotional capital are unclear.

Overall, scholars of emotional capital have faced three conceptual limitations. A lack of definitional clarity has blurred the distinction between capital as a resource versus capital as activated in practice. As a result, emotional experience and expression have been used as a proxy for an individual’s capital (Gillies 2006; Reay 2004). Past research has also verged on reproducing essentialist ideology (see Manion 2007 for a similar critique), presuming that women have capital while men do not, or a modified view that women have more capital than men (Nowotny 1981). Finally, comparing findings from Cahill (1999) with Schweingruber and Berns (2005) raises questions about emotional capital’s sensitivity to modification as a result of secondary socialization. As conceptual ambiguity “is the basic deficiency of social theory,” (Blumer 1969, p. 144), I now turn to empirical data from male nurses to clarify the concept of emotional capital and its role in a sociology of emotion practice.

Methods and data

This article draws on data collected from forty male nurses from the United States, including twenty-nine men who participated in in-depth interviews, five men who provided daily audio diary recordings after each of six nursing shifts, and six men who provided both diaries and interview data. Such data allow for an in-depth examination of men’s situational emotion practice on the job as well as their semi-structured reflections on the types of emotional resources they possess and use as nurses (Kenten 2010; Ragin et al. 2004; Worth 2009). Men in the traditionally feminine occupation of nursing are a distinct group that can provide unique reflections on emotional resources and practice. The potential disconnect between men’s masculine habitus and the feminine nature of carework can provide a dissonance that elucidates processes that might otherwise remain invisible and unconscious. Furthermore, diary methods are well-suited to capturing emotions as they unfold in everyday life (Theodosius 2006).

As part of a larger project on identity and emotion among registered nurses, audio diaries were collected from male nurses from spring 2011 through the fall of 2012 at a large Midwestern hospital system. Respondents participated in a training session on operating a voice recorder. They were instructed to reflect on memorable events and how they felt during and after the shift. Eleven men completed audio diaries, for a total of approximately 9.5 hours of recording. Interviews were conducted from the spring of 2012 through the spring of 2013. To supplement the eleven men recruited regionally, I solicited participants through a national nursing association and recruited twenty-nine more men to the study. Combined with the eleven from the regional hospital, a total of forty men participated. In conducting in-depth interviews, I relied on a script of open-ended questions that probed participants on the emotional demands of nursing, reflections on their care, and examples of the unique experiences they have had as men in the profession. All interviews and diaries were recorded and transcribed.

Participants were, on average, 44 years old, with 14 years of nursing experience (ranging from under-one to 39 years), and worked within a variety of units (pediatrics, emergency, intensive care, community health, primary care, psychiatric, etc.). Most participants identified as white, with three identifying as Latino/Hispanic, 2 African-American, and 1 who identified as “other.” Compared to national nursing data (Institute of Medicine 2011), Black/African-American and Asian nurses are underrepresented and Hispanic/ Latino nurses are overrepresented in the sample.

The analysis focused on men’s responses to questions concerning their ability to be compassionate and caring; their specific experiences with patients and co-workers; if and how they felt that being a man shaped their nursing care; and advice they would give to younger men interested in nursing. Using emotional capital as a “sensitizing concept” (Blumer 1969, p. 147) and knowledge of the literature as my guide (Ong 2012), I honed in on men’s descriptions of emotion as a possible resource. The analysis moved between the data and prior literature in an abductive fashion (Timmermans and Tavory 2012), attending to how male nurses distinguish between capacities versus practice, and if and how they developed emotional capacities and skills as a result of their training and time spent in the profession. Using men in nursing as a theoretically illustrative case, I address the three critiques noted in the above literature review.

Refining the concept of emotional capital

Emotional capital: feminine or neutral?

Contemporary cultural beliefs presume women’s greater competency in nurturing and caring for others (Ridgeway 2011). Yet, male nurses contest these beliefs. They overwhelmingly argued that they possess the capacity for compassion in a manner similar to their female colleagues. While recognizing the professional stakes that overlap such claims, this seems to echo the limited research on male nurses’ emotional capabilities (Codier and MacNaughton 2012). When asked about the stereotypic gender beliefs that men were not as nurturing or compassionate as women, participants claimed that this stereotype was patently false:

I don’t agree with that. I believe that men can [be] as caring as women. (ArtFootnote 3)

Of course they [men] are compassionate and caring. (Walter)

Male nurses contest the hegemonic, essentialist belief that men lack the capacity to experience these emotions (Connell 2005). By stating “of course,” Walter hints at the commonsensical nature of his belief that men are compassionate. Following Epstein’s (2007, p. 11) characterization of habitus as the internalized “patterns and behaviors that we view as commonsensical,” Walter’s phrasing suggests that this attitude is deeply held as embodied cultural capital -- an unimpeachable aspect of his habitus. It is unsurprising then that Walter boasts 17 years in the profession.

But men do differ from women, according to participants. Making an analytical distinction between capacity and expression, Ethan asserts that:

I think men have this full range of emotion [as] everybody else, but they’ve been acculturated not to express that to the degree that women are allowed to. (Ethan)

Ethan’s quote suggests that men have similar levels of emotional capital—capacity for a “full range of emotion”—but that they use this capital in different ways as a result of cultural norms that constrict men’s expression of emotions. Linked to dominant gender discourse and cultural beliefs (Ridgeway 2011), men and women may hold similar amounts of emotional capital, particularly in terms of capacity for feeling, but draw on and use this emotional capital in different ways in order to meet differing cultural and situational expectations.

While men affirm their capacity for care and compassion, they encounter others in the profession who disagree. Jason, for example, was told explicitly that men did not have the same emotional capacity as women:

My second year as a nurse, I had one of my managers told [sic] me that “for a guy you’re doing very well because guys are not capable of caring at the same level as a woman in a pediatric ICU.” (Jason)

Men confront diffuse gender beliefs espoused in our culture through managers, teachers, and co-workers who believe them to be less emotionally equipped for the profession (Snyder 2011).

Scholarly claims that men lack emotional capital of this sort may, in fact, be linked to gender ideology rather than empirical reality (for a similar critique, see Manion 2007). Alternatively, we might view men’s claims of equivalent emotional capacity as an exercise in power through which men seek to shore up a resource traditionally seen as feminine. As Swartz notes, “groups draw upon a variety of cultural, social, and symbolic resources in order to maintain and enhance their positions in the social order” (1997, p. 73). Facing an increasingly service-based economy with greater “affective requirements,” men may lay claim to the feminine qualities of nurturance and compassion in order to maintain economic relevance (Bulan et al. 1997). Men may downplay distinctions between men and women’s emotional capital because such distinctions might limit their economic advancement in the field of nursing. Emotional capital, as a distinct type of embodied cultural capital, is “used to exclude and unify people, not only lower status groups, but equals as well” (Lamont and Lareau 1988, p. 158).

Male nurses recognize the cultural stereotypes about men and emotion. For Ben, for example, such a belief fuels his motivation to prove his colleagues wrong:

I think the very same prejudices about men being not nurturing, not emotionally available works against me as well. And I think that, I don’t know if this is coming from me or my colleagues, probably both, but I feel like I need to prove that I’m capable and worthy of the profession that I can go into a room and sense if someone is uncomfortable and make them comfortable. (Ben)

Proving that he “can”—that he has the capacity, skills, and knowledge—Ben applies knowledge of the emotional states of others (“sense if someone is uncomfortable”) and skillfully manages their feelings of discomfort (“make them comfortable”). Criticisms of his claim to nurturance drive Ben to develop deft skills of emotion management. Beyond emotional capacity, Ben’s quote illustrates other facets of emotional capital—emotion-specific knowledge and skills.

While men claim equivalent capacities to care, the way that this care is expressed may be distinct. Alex, for example, argues that differences between male and female nurses lie in practice—the activation or embodiment of capital—and not capacity:

We [men and women] express our care and work with patients in different ways and there are times where I think there are some gender specific ways that we may behave but in general I don’t think that that gets in the way of being a caring nurse. (Alex)

True gender distinctions may arise in the expression of emotion and therefore the manner in which emotional capital is embodied and activated as practice in nursing. Turning to this difference, the next section examines how the situational use of emotional capital is distinct from emotional capital as a trans-situational resource.

Emotional capital and practice: capacity vs. expression

As the quotes above begin to suggest, a critical component of theorizing emotional capital is distinguishing the resource itself from the activation and embodiment of that resource through emotional experiences and management (i.e., emotion practice). Distinctions between capital and its activation have been fruitfully made in examinations of other forms of cultural capital (Merolla and Jackson 2014; Purcell 2013). Lareau and Weininger (2003), for example, use “possession” as distinct from the activation of capital. An individual possesses emotional resources that may be embodied or activated in distinct settings. Emotion practice involves the enactment/embodiment of emotional capital, while emotional capital is trans-situationally available regardless of its use in practice. Reay’s (2004) analysis confuses this issue by seeing a mother’s emotional support for her child’s education as emotional capital rather than emotion practice. Data from male nurses allows us to distinguish clearly between capital as a resource and the embodiment and enactment of that capital into practice. Just as other forms of cultural capital are mobilized or activated within situations, but remain trans-situationally available alongside the lasting dispositions of habitus (Bourdieu 1986), so too emotional capital is mobilized and embodied in the experience and management of emotion.

We saw in the above quotations that male nurses generally see themselves and other men as fully capable of feeling compassion and care for others—as holding similar emotional capacities and skills—as compared to women. However, they argue that they express their care differently as a result of their gendered location. This, they believe, explains the misconception that men do not care as much as women. Despite recognizing this difference, men in the sample were not always able to articulate how men and women express care differently in nursing:

[I]t’s definitely a different type of nurturing type thing. […] it’s hard to put my finger on it but I have been in the room, like a mothering type, female nurses become like the patient’s mother. Where I know I’m definitely not doing that. I think it’s just like a type of care that is given. As far as like I don’t think we have a word for it, like how males do that. […] I have a hard time putting my finger on it but I haven’t had anybody directly say, “you don’t care.” (Ron)

Ron contrasts his own style of care with a female nurse’s matronly style, but notes that he has difficulty describing what it is that distinguishes how he goes about providing care as a man from how his female colleagues provide care. His lack of clarity likely stems from the naturalization (and hence misrecognition) of the rules of the habitus that shape Ron’s emotion practice as a man. Despite having similar emotional resources as women, Ron argues that men embody that capital in distinct ways—ways that may even be unconscious and difficult to articulate. Emotion practice, then, should be conceptualized as the embodiment/activation of emotional capital that includes both conscious and nonconscious modes of being. Emotional capital exists alongside “long-lasting dispositions of both mind and body—in other words, in the form of habitus, and it is as much unconscious as conscious” (Virkki 2007, p. 278).

Explaining differences in care, participants highlight the cultural taboo that limits men’s affection and touch. Mason articulates this distinction for men and women in nursing:

A man in the situation can provide as much nurturing or just as much nurturing. The one reason I think a lot of people don’t see that is that we have to work within very strict parameters. (Mason)

Mason’s word choice here is key as he says men “can provide” as much nurturing as women. Men do not necessarily mobilize nurturing skills, but they do have access to those skills as trans-situational emotional resources. Men may still be “shielded” from performing emotional labor as a result of their status (Cottingham et al. 2015; Hochschild 1983). Mason goes on to describe how men’s touch can be potentially viewed as sexual and, as a result, men must express their care within the “strict parameters” of how others will interpret their actions. This limitation in comforting patients suggests that male nurses’ emotion management strategies (Cottingham 2015) might be reframed as alternative ways of mobilizing emotional capital.

Stating that he is not as “touchy-feely” as some of the female nurses, Russell, an ER nurse with 6 years of experience, suggests an individual explanation for not using physical touch in patient care rather than a social or cultural explanation. Russell discusses this as complementary (“one of the things that I bring different to the table than a lot of female nurses”) and not problematic. Russell also goes on to explain this approach as rooted in his primary socialization: “because of the way I was brought up.” This suggests a primary form of emotional capital linked to early family socialization rather than occupational or secondary socialization sources. Expanding on this distinction in the following section, I use the concepts primary and secondary emotional capital to examine the sources of men’s emotional resources.

Primary and secondary emotional capital

A third gap in the literature on emotional capital has been a failure to theorize it as an accumulated resource gained in early socialization—a process constrained by social location—while also susceptible to modification in educational (Froyum 2010) and occupational (Cahill 1999) settings. Socialization refers to the “quasi-magical” processes (Bourdieu 1990, p. 58) through which individuals form identities, values, beliefs, and habitual ways of being and doing. The family and early education are thought to exert the most influence because “the habitus tends to ensure its own constancy” (Bourdieu 1990 p. 60). However, secondary sources encountered later in life, including occupational training and education may influence emotional capital accumulation.

When asked if they had developed empathy, compassion, and care for others as a result of their work in a caring profession, men in nursing responded in ways that suggest a view of emotional capital as both a set of innate qualities brought to the profession and skills, capacities, and knowledge developed over time. While they argued that they had the capacity for empathy and compassion before entering the profession, their experiences in nursing and taking care of others helped them develop this capital further. Emotional capital in its embodied form is rarely seen as something one has, but who one is. This is in keeping with Bourdieu’s theorizing on embodied capital when he says that “What is ‘learned by body’ is not something that one has, like knowledge that can be brandished, but something that one is” (Bourdieu 1990, p. 73). But this does not mean that embodied capital is innate or inherent to the body. Rather it is through the social process of accumulating and embodying capital that “fundamental social choices” come to be seen as natural and inevitable (Bourdieu 1990, p. 71). And in this way mechanisms of power can remain undetected.

Thus, while men see differences in innate characteristics and developed emotional resources, I use the terms primary and secondary capital to conceptualize capital as a social resource linked to primary socialization in the family and school as well as susceptible to expansion and modification through occupational training. These terms also help to distinguish emotional capital from trait-based, personality theories of the individual.

Several male nurses emphasized empathy as part of who they are—hence linked to habitus and primary capital—rather than a capacity developed on the job:

I think some people are naturally predisposed to being more empathetic and I think I’m one of those people. (Carl)

I think that some people were just born to have compassion and [be] caring. (Walter)

Adding to the description, Max sees the capacity for compassion as both innate and developed:

I think that I’ve always had it [capacity for compassion] and I do think that because of nursing it has developed and gotten stronger. (Max)

Max’s description highlights the tension between primary and secondary sources of socialization. Critiques of Bourdieu’s conception of habitus, capital, and practice have argued that, in an effort to explain the reproduction of inequalities, he paints an overly deterministic portrait of social life, and of class inequality in particular (Jenkins 1982). Using the term primary emotional capital connotes the more rigid, socially constrained aspects of habitus developed during formative years that individuals bring to bear within various situations. Such forms of capital are likely to be seen by individuals as innately linked to who one is, rather than a resource that one possesses.

Secondary capital complements this concept by making room for agentive efforts to shape and modify emotional resources and, in theory, the habitus. While socialization is often characterized as an outside force that acts upon individuals, secondary emotional capital can be actively accumulated as individuals seek to meet practical goals. This type of capital may be more easily recognized as a resource that one has rather than an innate feature of who one is. We can also think about the commonsensical terms that individuals use in discussing their everyday social practice. Terms like “of course,” “obviously,” and “naturally” can point to elements of the self that individuals take for granted as part of their primary capital. We might also see this in an individual’s inability to articulate an element of their social practice as in the case of one of the first quotes from Walter.

Similar to Max above, Ben discusses the primary “emotional framework” that he received from male members of his family, as well as how his primary emotional capital was modified over the course of taking care of his chronically ill mother:

So when I was a kid, there were a couple—my dad, a couple other uncles, […] are also sensitive and communicative, at least they were when I was younger. We talked about love and we talked about life and I really loved the guys that helped me become emotionally aware of myself, emotionally intelligent as much as possible, there’s always room for growth. So that I think laid the emotional framework for me, then there’s also just who you are as a person I think that plays some part, an inexplicable part.

My mom became chronically ill about 7 years ago, she got diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and I’ve been a caretaker for her. […] My relationship for her got better and I guess I kind of go back and forth between being a son and a caretaker for her and it’s helped me be a lot more patient being a caretaker for her. (Ben)

Ben notes the specific men in his life that helped him become “emotionally aware” during his childhood socialization. With this primary capital as a “framework” for him, he later notes that his time as a caretaker further developed his emotional capital, namely his skill in managing his feelings of annoyance and/or frustration—i.e., becoming more patient. This secondary emotional capital linked to his adult experience as a caretaker for his mother, suggesting that an individuals’ emotional capital is malleable to different situational experiences. This narrative is similar to Stacey’s (2011) findings concerning home care aides. Caring for others informally in an unpaid setting helped aides in her study develop the emotional capital that they would later transfer to paid work.

Carl describes empathy as stemming from primary socialization as well as concerted introspection and experience:

Empathy is really something you can develop, not everyone really thinks about it. If you’re someone who reflects a lot and you’re put in those situations, you try to understand what that person feels and that’s something I’ve done my whole life. (Carl)

The capacity for empathy forms part of Carl’s primary emotional capital—“something I’ve done my whole life”—while also being susceptible to modification through reflection and experience. Carl later notes that you have to become “a chameleon to a certain extent and adapt to situations” in order to care for others. Such adaptation might be framed in terms of “emotional reflexivity,” as men are able to assess the emotions of others and adapt their behavior accordingly (Holmes 2010, 2015). Working in the field of healthcare, men’s experiences help them develop their emotional capital, including the ability to read and respond to the emotions of others. In this way, emotion practice can lead to new capital as individuals confront new situational demands and engage in reflexivity.

But Carl’s capacity to empathize has its limits:

It’s always hard to be empathetic with parents when there’s [sic] suspected cases of abuse. […] It is hard to be empathetic to that parent. Certainly more, I can understand, for instance with shaken babies. I can understand the frustration of having a colicky baby and to how it just might make you crazy. I can empathize with that. […] But it’s hard; those are the times where it’s really hard to empathize. (Carl)

Here Carl still makes a concerted effort to put himself in the position of a parent with a colicky baby and imagine how that might frustrate a parent. Where others might demonize abusive parents as abhorrent, Carl taps the limits of his empathic resources.

Other male nurses see the capacity for compassion and empathy as effortful (has to be “reached for”) and potentially developed over time through teaching and situations encountered later in life:

It’s hard to find compassion for that—when they calmly tell you my pain is 14 out of 10 and then go back to laughing and joking on the phone. […] It’s not a terrible experience, but it’s one where you have to really reach for the compassion, you know? (Max)

Yeah, I think you can teach them [nurses] that [empathy]. I think [for] most people you can help them develop what they have and how to use it better. I do think there are some people, and they’re usually called sociopaths, that don’t have that ability. (Carl)

Or after somebody has a bowel movement, and you clean them, using a nice one of those wet wipes to just make it nice and clean and put a little powder, simple basic stuff like that. Seeing how that can totally change somebody’s mood. I think that’s really powerful and somebody who does not become more empathetic after a few of those experiences is a sociopath. (Ben)

Max, confronting situations that test the limits of his capacity for compassion, must “reach for the compassion,” suggesting that through difficult occupational experiences he extends his capacity for feeling, and with it his emotional capital. Carl believes that empathy is teachable and distinguishes between helping others “develop what they have” (capital) and “how to use it better” (practice). Ben frames nursing as a set of skills that alleviate suffering. By exercising those skills and seeing the effect on others’ emotional state, nurses necessarily “become more empathetic”—developing their emotional capital through practice.

In pathologizing individuals without empathy as sociopaths, Carl and Ben mark boundaries between themselves and “uncaring others” in a manner similar to the home care aides in Stacey’s ethnographic work (2011, p. 117). Virkki (2007) theorizes this type of demarcation using Bourdieu: “For Bourdieu, the formation of one’s capital is based on social exclusion: one’s possession of capital requires that some others lack it” (p. 275). In this way, emotional capital marks social boundaries and maintains hierarchies of distinction, making it a force for stratification. Unlike the social workers and nurses in Virkki’s study who distinguished themselves from emotionally “illiterate” clients, men in the current study use an extreme group of stigmatized others—sociopaths—to distinguish themselves socially. Male nurses seem to simultaneously erase distinctions between themselves and female nurses while highlighting their superiority in comparison to the emotionally inept. This demarcation bolsters men’s claim to emotional capital while also minimizing the scarcity of these resources. If only sociopaths lack these resources, their value is diminished and their conversion into other forms of capital such as monetary value may be limited.

Discussion and conclusion

A review of prior conceptualizations of emotional capital reveals three gaps that limit the utility of the concept. These include: contradictions in the conception of emotional capital in relation to gender; the use of emotional capital interchangeably with management and experience; and a failure to distinguish primary from secondary capital sources. Attending to these gaps, I use data from men in nursing to illustrate that men, though culturally assumed to hold limited emotional capital, lay claim to emotional resources and see their capacity for compassion as similar to women’s despite differences in activating that capital. Emotional capital can be developed over the course of occupational experiences and is a vital concept for understanding emotion’s role in social practice. While the experiences of men in nursing suggest a tension between primary emotional capital (perceived as “innate”) and secondary emotional capital developed on the job, it is critical that future work attempt to tease out which aspects of emotional capital are more rigidly fixed within the habitus during primary socialization versus those susceptible to change through secondary socialization. Cahill’s (1999) study of mortuary students, for example, suggests that occupational training was insufficient for developing the emotional resources that students with a mortuary background took for granted.

Emotional resources are embodied and activated through emotional experience and management as an everyday feeling/doing practice at the conscious and nonconscious level. As part of the trans-situational, but field-specific habitus, emotional capital operates in tandem with other forms of cultural capital as a “feel for the game” (Bourdieu 1990). Not seen as naturally caring, men argue that caring, compassion, and empathy are things they “can” do. Their status as men in a caring profession renders aspects of their “feel for the game” effortful rather than natural. While men and women’s use of capital likely differs, some prior literature has framed emotional capital as an exclusively feminine resource, perhaps in an effort to raise its value by emphasizing its scarcity. This conceptual power move may increase the value of emotions and carework, but it has unnecessarily limited the theoretical reach of the concept. Men’s claim to such capital, likewise, may represent an attempt to maintain economic relevance, and thus power, in the care-based field of nursing. Here, male nurses might be seen as “capital accumulating subjects” (Huppatz 2006, p. 129) who must accumulate emotional capital in order to adapt masculine, “durable dispositions” (Bourdieu 1990, p. 62) to the economic and social conditions of the twenty-first-century labor market.

I am also arguing for a clearer distinction between emotional capital and practice. This can allow for a better conception of how emotional capital is converted into other forms of capital. Nowotny’s (1981) early considerations suggest that “different rules of conversion of capital” (148) might exist between men and women. While we might question Nowotny’s claim that emotional capital is only accumulated in the private sphere, her suggestion of gendered rules of capital conversion might explain men’s advantage in female-dominated occupations (Williams 1992). Ben’s narrative suggests that “proving” his colleagues wrong concerning men’s lack of capacity for care and compassion fueled his emotion practice on the job. By activating capital, men may prove their resources to others, meet professional norms, and challenge the constraints of a masculine habitus. These moves convey agency in a manner that distinguishes them from their female colleagues—colleagues whose capital and feel for the game may be less conscious and hence less socially recognized and rewarded. And yet, by claiming that only sociopaths lack empathic resources, male nurses undercut the scarcity and potential economic value into which emotional capital might be converted. If empathy is a resource that everyone has, there is no need to pay a premium for its convincing embodiment.

Male nurses, by their very position as men in a caring profession, call into question assumptions about “innate” feeling capacities and skills. Here, distinctions between primary and secondary emotional capital are useful for emotion and gender theory. Dominant discourses dichotomize reason and emotion while conflating women with the emotional (Ridgeway 2011). Prior work on emotional capital has reaffirmed this ideology, often assuming that women’s gendered experiences and socialization inherently lead to emotional capital acquisition. Male nurses’ discussion of primary and secondary emotional capital implicates a more nuanced triadic relationship among reason, gender, and emotion. Participants argue that through experiences, self-reflection, and conscientious teaching and learning empathic capacities may develop. Rather than see emotional capacities, skills, and knowledge as overly determined by one’s gender-socialization, men might actively acquire knowledge and skills in order to meet the practical demands of their work. This, in turn, modifies the trans-situational emotional resources linked to habitus. These capacities are not solely linked to their gender nor to their primary socialization, but are shaped through the reciprocal relationship between an individual’s active “reaching” and the practical demands of nursing.

While noting that self-reflexivity and practical experiences can be a source of developing emotional capital, these elements are also shaped by social location and other forms of capital. Although working in the theoretical tradition of Giddens, Lupton notes that self-reflexivity requires “the cultural and material resources” of those who are advantaged (1999, p. 116). Education provides the means to engage in self-reflexivity and, in turn, develop emotional capital through self-reflexivity. Experiences, too, are shaped by social, cultural, and economic capital, while also providing the practical conditions in which emotional capital might develop. Here though it is important to note that different experiences might lead to different configurations of emotional capital rather than more or less of it. While I focus here on the field of healthcare and nursing, other fields that may appear more traditionally masculine such as war, sports, or fatherhood (Wall and Arnold 2007) might also be sites in which men develop and use emotional capital (though different aspects of emotional capital may come to be seen as scarce and valued in these different fields). Similarly, future research could assess how emotional capital is developed through primary socialization by looking at how children acquire emotion-based knowledge, skills, and capacities rather than assessing maternal emotions as indicators of capital transfer.

Case study data from men in nursing illustrate men’s possible access to emotional capital. These data also reveal the relationship between emotional capital as a trans-situational resource and emotion practice as situationally embodied and mobilized capital, as well as the utility of distinguishing capital based on primary and secondary socialization sources. Theorists and emotion scholars should account for these distinctions and processes in future work. Using emotional capital as part of a larger emotion-as-practice perspective (Erickson and Stacey 2013; Scheer 2012), scholars can develop the sociology of emotion in a way that links social psychological processes to systemic factors and, in doing so, revitalize the relevance of emotion for broad sociological inquiry.

Notes

In line with Bourdieu’s discussion of economic competencies and capacity (Bourdieu 1990, p. 64), I view emotional competence like “all competence (linguistic, political, etc.), far from being a simple technical capacity acquired in certain conditions, [it] is a power tacitly conferred on those who have power over the economy or (as the very ambiguity of the word “competence” indicates) an attribute of status.” There are no elements of emotional capital that are outside of power relations (just as no elements of capital exist outside of social relations). All resources have the potential to be used to create social distinction and hence can be used as an exercise of power. How specific resources become linked to power stems from the historic development of the field under investigation.

Reay has recently shifted away from a focus on emotional capital toward Bourdieu’s concept of habitus. I agree with Reay that merely “expanding the array of capitals” (2015, p. 9) for its own sake is not satisfying, but I see the shortcomings of prior work on emotional capital in terms of the three limitations laid out here as well as in insufficient consideration of the interrelationships among capital, habitus, and practice. Shifting to habitus, rather than capital, does not help us clarify the linkages among these important concepts. Capital, I believe, remains a useful term for understanding the connections among structural position, power, and the individual in a way that an exclusive focus on the psyche does not.

All names are pseudonyms and italics have been added to quotations for emphasis.

References

Adkins, L. (2004). Introduction: feminism, Bourdieu and after. The Sociological Review, 52, 1–18.

Archer, M. (1990). Human agency and social structure: a critique of Giddens. In Anthony Giddens: consensus and controversy (pp. 73–84). London: The Falmer Press.

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. E. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory of research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. (R. Nice, Trans.). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1996). Distinction: a social critique of the judgement of taste. (R. Nice, Trans.). London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (2004). The peasant and his body. Ethnography, 5(4), 579–599.

Brown, M. (2005). In the bad or good of girlhood: social class, schooling, and white femininities. In L. Weis & M. Fine (Eds.), Beyond silenced voices: class, race, and gender in United States schools (pp. 147–162). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Bulan, H. F., Erickson, R. J., & Wharton, A. S. (1997). Doing for others on the job: the affective requirements of service work, gender, and emotional well-being. Social Problems, 44(2), 235–256.

Cahill, S. E. (1999). Emotional capital and professional socialization: the case of mortuary science students (and me). Social Psychology Quarterly 62 (2), 101–116.

Chaplin, T. M., Cole, P. M., & Zahn-Waxler, C. (2005). Parental socialization of emotion expression: gender differences and relations to child adjustment. Emotion, 5(1), 80–88. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.80.

Codier, E., & MacNaughton, N. S. (2012). Are male nurses emotionally intelligent? Nursing Management, 43(4), 1–4.

Colley, H. (2006). Learning to labor with feeling: class, gender, and emotion in childcare education and training. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 7(1), 15–29.

Connell, R. W. (2005). Masculinities (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cottingham, M. D. (2015). Learning to “deal” and “de-escalate”: how men in nursing manage self and patient emotions. Sociological Inquiry, 85(1), 75–99. doi:10.1111/soin.12064.

Cottingham, M. D., Erickson, R. J., & Diefendorff, J. M. (2015). Examining men’s status shield and status bonus: how gender frames the emotional labor and job satisfaction of nurses. Sex Roles, 72(7–8), 377–389. doi:10.1007/s11199-014-0419-z.

DiMaggio, P. (1979). On Pierre Bourdieu. American Journal of Sociology, 84(6), 1460–1474.

Emirbayer, M., & Desmond, M. (2012). Race and reflexivity. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35(4), 574–599. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.606910.

Emirbayer, M., & Goldberg, C. A. (2005). Pragmatism, Bourdieu, and collective emotions in contentious politics. Theory and Society, 34(5–6), 469–518.

Epstein, I. (2007). Education, comparison, and the challenges of an embodied perspective. In I. Epstein (Ed.), Recapturing the personal: essays on education and embodied knowledge in comparative perspective (pp. 1–21). Charlot: Information Age Publishing.

Erickson, R. J., & Stacey, C. (2013). Attending to mind and body: engaging the complexity of emotion practice among caring professionals. In A. A. Grandey, J. M. Diefendorff, & D. E. Rupp (Eds.), Emotional labor in the twenty-first century: diverse perspectives on emotion regulation at work (pp. 175–196). New York: Routledge.

Froyum, C. (2010). The reproduction of inequalities through emotional capital: the case of socializing low-income black girls. Qualitative Sociology, 33, 37–54.

Fuchs, S. (2001). Beyond agency. Sociological Theory, 19(1), 24–40.

Garside, R. B., & Klimes-Dougan, B. (2002). Socialization of discrete negative emotions: gender differences and links with psychological distress. Sex Roles, 47(3–4), 115–128.

Gendron, B. (2004). Why emotional capital matters in education and labour? Toward an optimal exploitation of human capital and knowledge management. Les Cahiers de La Maison Des Sciences Economiques, 113, 1–37.

Gillies, V. (2006). Working class mothers and school life: exploring the role of emotional capital. Gender and Education, 18(3), 281–293.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. NY: Bantam.

Hochschild, A. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. The American Journal of Sociology, 85(3), 551–575.

Hochschild, A. (1983). The managed heart: commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Holmes, M. (2010). The emotionalization of reflexivity. Sociology, 44(1), 139–154. doi:10.1177/0038038509351616.

Holmes, M. (2015). Men’s emotions: heteromasculinity, emotional reflexivity, and intimate relationships. Men and Masculinities, 18(2), 176–192. doi:10.1177/1097184X14557494.

Huppatz, K. (2006). The interaction of gender and class in nursing: appropriating Bourdieu and adding Butler. Health Sociology Review, 15(2), 124–131.

Husso, M., & Hirvonen, H. (2012). Gendered agency and emotions in the field of care work. Gender, Work and Organization, 19(1), 29–51.

Institute of Medicine (2011). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/12956.

Jackson, E. N. (1959). Grief and religion. In H. Feifel (Ed.), The meaning of death (pp. 218–233). NY: McGraw-Hill.

Jenkins, R. (1982). Pierre Bourdieu and the reproduction of determinism. Sociology, 16(2), 270–281.

Kenten, C. (2010). Narrating oneself: reflections on the use of solicited diaries with diary interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research (Vol. 11). Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/viewArticle/1314.

King, A. (2000). Thinking with Bourdieu against Bourdieu: a “practical” critique of the habitus. Sociological Theory, 18(3), 417–433.

Lamont, M., & Lareau, A. (1988). Cultural capital: allusions, gaps and glissandos in recent theoretical developments. Sociological Theory, 6(2), 153. doi:10.2307/202113.

Lareau, A., & Weininger, E. B. (2003). Cultural capital in educational research: a critical assessment. Theory and Society, 32(5–6), 567–606.

Lupton, D. (1999). Risk. London: Routledge.

Manion, C. (2007). Feeling, thinking, doing: emotional capital, empowerment, and women’s education. In I. Epstein (Ed.), Recapturing the personal: essays on education and embodied knowledge in comparative perspective (pp. 87–109). Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

McCarthy, E. D. (1989). Emotions are social things: an essay in the sociology of emotions. In The sociology of emotions: original essays and research papers (pp. 51–72). Greenwich: JAI Press.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, & society. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Merolla, D. M., & Jackson, O. (2014). Understanding differences in college enrollment: race, class and cultural capital. Race and Social Problems, 6(3), 280–292. doi:10.1007/s12552-014-9124-3.

Nash, R. (2003). Social explanation and socialization: on Bourdieu and the structure, disposition, practice scheme. The Sociological Review, 51(1), 43–62.

Nixon, C. A. (2011). Working-class lesbian parents’ emotional engagement with their children’s education: intersections of class and sexuality. Sexualities, 14(1), 77–99.

Nowotny, H. (1981). Austria: Women in public life. In C. F. Epstein & R. L. Coser (Eds.), Access to power: cross-national studies of women and elites (pp. 147–156). London: George Allen & Unwin.

O’Brien, M. (2008). Gendered capital: emotional capital and mothers’ care work in education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29(2), 137–148.

Ong, B. K. (2012). Grounded theory method (GTM) and the abductive research strategy (ARS): a critical analysis of their differences. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(5), 417–432. doi:10.1080/13645579.2011.607003.

Pierce, J. (1995). Gender trials: emotional lives of contemporary law firms. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Purcell, D. (2013). Baseball, beer, and Bulgari: examining cultural capital and gender inequality in a retail fashion corporation. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 42(3), 291–319.

Ragin, C. C., Nagel, J., & White, P. (2004). Report on “Workshop on Scientific Foundations of Qualitative Research.” National Science Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2004/nsf04219/nsf04219.pdf.

Reay, D. (2000). A useful extension of Bourdieu’s conceptual framework? Emotional capital as a way of understanding mothers’ involvement in their hildren’s education. The Sociological Review, 48, 568–585.

Reay, D. (2004). Gendering Bourdieu’s concepts of capitals? Emotional capital, women, and social class. The Sociological Review, 52, 57–74.

Reay, D. (2015). Habitus and the psychosocial: Bourdieu with feelings. Cambridge Journal of Education, 45(1), 9–23. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2014.990420.

Reid, C. (2009). Schooling responses to youth crime: building emotional capital. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13(6), 617–631.

Ridgeway, C. (2011). Framed by gender: how gender inequality persists in the modern world. NY: Oxford University Press.

Ryder, N. B. (1965). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review, 30, 843–861.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Imagination, cognition and personality. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 195–211.

Scheer, M. (2012). Are emotions a kind of practice (and is that what makes them have a history)? A Bourdieuian approach to understanding emotion. History and Theory, 51(2), 193–220.

Scheper-Hughes, N., & Lock, M. M. (1987). The mindful body: a prolegomenon to future work in medical anthropology. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 1(1), 6–41.

Schweingruber, D., & Berns, N. (2005). Shaping the selves of young salespeople through emotion management. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 34(6), 679–706.

Shott, S. (1979). Emotion and social life: a symbolic interactionist analysis. American Journal of Sociology, 84, 1317–1334.

Singh-Manoux, A., & Marmot, M. (2005). Role of socialization in explaining social inequalities in health. Social Science & Medicine, 60(9), 2129–2133. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.070.

Skeggs, B. (2004). Context and background: Pierre Bourdieu’s analysis of class, gender and sexuality. The Sociological Review, 52, 19–33. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00522.x.

Snyder, K. A. (2011). Insider knowledge and male nurses: how men become registered nurses. In Research in the sociology of health care (Vol. 29, pp. 21–41). Greenwich, Conn: JAI press. doi:10.1108/S0275-4959(2011)0000029004.

Stacey, C. (2011). The caring self: work experiences of home care aides. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Swartz, D. (1997). Culture & power: the sociology of Pierre Bourdieu. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Theodosius, C. (2006). Recovering emotion from emotion management. Sociology, 40(5), 893–910. doi:10.1177/0038038506067512.

Thoits, P. A. (2004). Emotion norms, emotion work, and social order. In S. R. Manstead, N. Frijda, & A. Fischer (Eds.), Feelings and emotions (pp. 359–378). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Timmermans, S., & Tavory, I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: from grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory, 30(3), 167–186. doi:10.1177/0735275112457914.

Virkki, T. (2007). Emotional capital in caring work. In Research on emotions in organizations (Vol. 3, pp. 265–285). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group.

Wall, G., & Arnold, S. (2007). How involved is involved fathering? An exploration of the contemporary culture of fatherhood. Gender and Society, 21(4), 508–527. doi:10.1177/0891243207304973.

Williams, C. L. (1992). The glass escalator: hidden advantages for men in the “female” professions. Social Problems, 39(3), 253–267.

Wingfield, A. H. (2010). Caring, curing, and the community: black masculinity in a feminized profession. In Research in the Sociology of Work (Vol. 20, pp. 15–37). Greenwich, Conn: JAI press.

Worth, N. (2009). Making use of audio diaries in research with young people: examining narrative, participation and audience. Sociological Research Online, 14(4), 9. doi: 10.5153/sro.1967.

Zemblyas, M. (2007). Emotional capital and education: theoretical insights from Bourdieu. British Journal of Educational Studies, 55(4), 443–463.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here uses data from a larger study, “Identity and Emotional Management Control in Health Care Settings,” funded by the National Science Foundation (SES-1024271) and awarded to Rebecca J. Erickson (PI) and James M. Diefendorff (Co-PI). Participant compensation and research travel was also made possible through the financial support of the Barbara J. Stephens Dissertation Award from the University of Akron, Department of Sociology. I especially thank Becky Erickson for her careful reading and constructive criticism of earlier drafts. I also thank Clare Stacey, Rob Peralta, Kathy Feltey, Janice Yoder, and the editors and anonymous reviewers for Theory and Society for their valuable feedback on prior drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cottingham, M.D. Theorizing emotional capital. Theor Soc 45, 451–470 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-016-9278-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-016-9278-7