Abstract

The aim of the study is to explore the diachrony of orality and literacy in the Old East Slavic birch-bark corpus. One of the most striking characteristics of the birch-bark documents is their high degree of orality. Due to their rootedness in the communication situation, they possess many linguistic and pragmatic features that are typical for spoken discourse. In addition, they show clear signs of literacy, i.e., properties that are common for the written word in general as well as features that typically occur in Church Slavic documents, the model corpus for literacy in Old Rus’. Considering the long period that is covered by birch bark literacy we may assume that the relation between orality and literacy features changed over time. To uncover these changes, the author analyzes the diachronic development of selected lexical, morphological, and syntactic features that characterize different registers and thus serve as markers of literacy or orality. The results support the thesis that Church Slavic bookishness, the initial model for literacy, was replaced by another model, namely non-bookish, official writing on parchment. Over time, the birch bark documents lost the features of literacy that were the immediate impact of Church Slavic writing, and adapted writing practices that were typical for non-bookish parchment documents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

After the in-depth analysis and understanding of the graphical, morphological, and syntactic aspects of the Old East Slavic birch-bark documents, the attention of “berestologists” has turned to their pragmatic and sociolinguistic features. One of the most salient pragmatic characteristics of birch-bark literacy is their high degree of “orality”.Footnote 1 Birch-bark writing is characterized by several features that are typical for spoken discourse, which is, in turn, a corollary from their being firmly embedded in the immediate communication situation.

Since writing practices change over time, and since the birch-bark corpus covers more than four centuries, we would expect to see changes in the oral quality of birch-bark writing, or, to put it more generally, a shift in the relation of orality and literacy features. Dekker’s analyses of selected phenomena shows that there was progress to more literacy over time (cf. Dekker 2018a, 2022). There are also indications that the development was not unidirectional. The study of address formulae and of the use of the vernacular script point to a shift away from literacy.Footnote 2 However, to date there is no comprehensive study of these processes. The aim of this paper is to propose a more systematic account of the diachrony of the orality–literacy dichotomy in the birch-bark documents by analyzing the development of selected lexical, morphological, and syntactic features that are typical for certain registers and evaluating their role in the development of orality or literacy in birch-bark writing.

2 Birch-bark literacy

The earliest birch bark documents date from the mid-11th century, the oldest extant ecclesiastical documents are from the same period. While there are no doubts that the official Conversion in 988 was the trigger for church-related writing, the origins of writing on birch bark and its relation to ecclesiastical writing is less clear. According to Franklin, there had been a separate, independent thread of secular writing that even predated Christianization and fed into different types of secular writing including the birch-bark documents. His arguments and conclusions are based on the existence of a few script-bearing objects such as the Gnezdovo inscription from the early 10th century, and on deliberations over how and when the inhabitants of Rusʹ could have come in contact with the written word (Franklin, 2002, pp. 121–127). Gippius disputes the existence of pre-Christian “native use of Slav script” (2011, p. 227), arguing that there is no compelling evidence for such an assumption. The documents Franklin and others claim to be witnesses of such early literacy, are, so Gippius, either of unclear origin (e.g., due to unreliable dating), or are not necessarily an example of Slavic script.Footnote 3 For Gippius, “Slav writing” in Rusʹ starts in the wake of the Conversion. The emergence of writing on birch bark as a manifestation of “lay practical writing” (Gippius, 2012, p. 225) is closely connected to confessional writing. Birch-bark writing continues the tradition of oral messaging, but according to Gippius ultimately had its roots in the Christian tradition and was “a spontaneous by-product of the spread of Christian education” (Gippius, 2012, p. 237). The birch-bark documents were the result of the convergence of “writing as a fundamental attribute of Christian culture” and “the oral practices of everyday urban life” (Gippius, 2012, p. 242). Gippius argues that this dual origin is the reason for the socio-linguistic and pragmatic variation displayed in the birch-bark documents:

“[…] as a piece of writing, the birchbark letter belongs to the periphery of Slavonic literary tradition founded by Sts Cyrill and Methodius. Although in the hierarchy of literary genres comprising this tradition pragmatic birchbark writing occupied the lowest end, its concrete examples may or may not reveal the writers’ orientation towards the higher levels of the hierarchy. The use of Cyrillic script for practical purposes left plenty of room for variation on different levels. Much depended here on the competence and literary ambitions of a scribe. Handwriting may be professional or that of an amateur; orthography may be the same as that of the church manuscripts or deviate from it […], and the language (phonetics and morphology) may be pure Old Novgorod dialect or its ‘standardised’ version, avoiding the most salient local features as non-prestigious. And last but not least, vocabulary and phraseology may or may not be influenced by Church Slavonic.” (Gippius, 2012, p. 245)

Even though the use of Church Slavic elements especially in early birch-bark writing seems to support Gippius’s thesis, we will probably never know whether secular pragmatic writing emerged independently of ecclesiastical writing or not. For the purposes of my investigation, the eventual origin of secular writing is not relevant, therefore I will not dwell on the topic.

3 The data

The birch-bark corpus is a difficult corpus when it comes to the study of diachronic change and variation, despite the fact that it stretches over more than four centuries. Firstly, it is not very big. According to Drevnerusskie berestjanye gramoty (DBG) the excavations have unearthed 1223 documents,Footnote 4 most of which are quite short and often badly damaged. Secondly, they are not evenly distributed chronologically, which at times makes it hard to assess diachronic developments. Figure 1 shows the chronological distribution (periodization and dating are taken from DBG). At first, there is a steady increase of birch-bark documents with a peak in the late 12th century (up to 180 documents in a two-decade period). This is followed by a sharp and sudden decline. Between the second decade of the 13th century and the mid-14th century the number of birch barks was relatively low, ranging from 20 to less than 60 documents in a two-decade period. Then there was a second increase followed by a second peak, but not as high as the first one (up to 100 in a 20-year period). After that the number of documents decreased and finally ran dry towards the end of the 15th century.Footnote 5

All this makes a quantitative analysis and the interpretation of data across time a challenging task. In this study I will confine myself to a mere description of the frequency of certain features over time in relation to the overall number of birchbark documents.

I considered all birch-bark documents published on DBG, i.e., all birch barks excavated until the excavation season 2021. A short survey of the 2022 documents displayed in Sičinava (2022) did not produce data that would substantially change my findings.

4 The orality – literacy continuum

The well-known dichotomy of literacy and orality (cf. Koch, 1985; Koch & Oesterreicher, 19861986, 1994) targets different communicative strategies. The orality: literacy dichotomy is independent of the medial transmission of the message (i.e., speaking vs. writing) and is a non-binary concept that allows intermediate stages and gradual shifts. Literacy and orality manifest themselves in specific linguistic and pragmatic phenomena. Some of them are universal, while others are language specific. The universal features originate in the respective prototypical communication situations of spoken and written discourse. On a universal level, a high degree of literacy means above all elaboration on all linguistic levels (high degree of lexical differentiation, hierarchically ordered syntactic constructions, etc.) as well as the absence of elements that indicate speaker attitude. Texts at the “oral end” of the continuum typically show less lexical elaboration, coordination rather than subordination, self-corrections, expressions relating to speaker attitude, etc. (Koch & Oesterreicher, 19941994, 1986, p. 27).

Language specific features do not necessarily originate in the different communication situations. They are linked to text models that are prototypical for either spoken or written discourse. If a document that exemplifies a bookish style within a certain speech community the linguistic features that distinguish it from other registers count as features of literacy. The same applies, mutatis mutandis, to oral language and vernacular documents.

4.1 Orality and literacy in the birch-bark documents

The bookish model in Old Rusʹ is represented by the Church Slavic text corpus. Church Slavic features that are different from the features we usually find in non-bookish texts are per se features of literacy, on any linguistic level.

The oral nature of writing on birch bark has been a topic in the study of birch-bark manuscripts since Aleksej Gippius’s seminal article from 2004. A birchbark document is firmly rooted in the communication act. Often it is not even the main element of the act, but plays a mere supporting role (Gippius, 2004, pp. 184–185). This situation regularly results in so-called communicative heterogeneity (term coined by Gippius, 2004, see also Dekker, 2018a, pp. 14–30 and Schaeken, 2019, pp. 159–169 for discussion), i.e., the convergence of more than one communicative act on one physical piece of birch bark. A birch bark may include two messages to two different addressees (e.g., N358,Footnote 6 Gippius, 2004, pp. 189–190; N831, Gippius, 2004, pp. 224–226), two messages from different addressers (e.g., N952, Janin & Zaliznjak, 2015, pp. 46–49), a direct reference to the messenger (e.g., N406, N771, N879, Smolensk 12, Gippius, 2004, pp. 199–203; Schaeken, 2014), even a message and its answer (N497, Schaeken 2011, 2014, pp. 156–158). The almost complete integration in the communication situation may also have a bearing on the usage of grammatical devices such as the imperative subject (Dekker 2014, 2018a, pp. 51–70).Footnote 7

In addition, the birch-bark documents show clear characteristics of literacy. Most messages are obviously carefully crafted. They are usually well organized, concisely formulated and informationally dense, spelling or writing errors are rather rare (Zaliznjak, 1987, pp. 181–182; 2004, passim; Gippius, 2019, pp. 51–52). Many of the letters adhere to a strict form. They begin with an address formula, followed by a clearly stated topic of concern, some end with a closing formula (Zaliznjak, 1987). We also find traces of literacy on a purely linguistic level, such as the use of Church Slavic lexical items, bookish morphological forms, and syntactic constructions.

If we look at orality and literacy from a diachronic perspective, we get a complex picture. Writing on birch bark seemed to have gained literacy, at least when it comes to certain features, such as speech reporting (Dekker, 2018a, pp. 71–114), or the changing role of the messenger (Lazar, 2014, p. 140).

There are also indications to the opposite development. In some respects, the writing on birch bark moved away from the models used in Church Slavic, a process that can be interpreted as a loss of literacy. One of these features is the evolution of address formulae, which has been described in great detail (Worth, 1984; Zaliznjak, 1987, pp. 150–159; 2004, pp. 36–37; Gippius 2009, 2012, pp. 245–249). The birch-bark documents possess several ways of addressing the recipient and none of them was consistently used over the whole time span of birch-bark literacy. The opening form poklanjanie and the closing form tsěluju tja are Church Slavic expressions and mostly occur in the early birch-bark documents, while East Slavic poklonъ belongs to a later period.Footnote 8 At the same time, the replacement of elements that explicitly refer to oral communication such as X molvitь tobě ‘X says to you’ by more neutral expressions (oтъ X-a kъ Y-u ‘from X to Y’; Gippius, 2009, pp. 291–292) is a development away from orality. The address formulae also became more diverse, more tuned to the addressee, with an overall growth of the expression of servility (Ru. rabolepie, Zaliznjak, 1987, p. 159). This probably reflects the fact that the agents in communication by birch bark became more socially differentiated (Zaliznjak, 1987; Gippius, 2009).

There are also two sides to the evolution of spelling practices. In Old Novgorod two orthographic systems were in use: the knižnaja sistema (bookish system) and the bytovaja sistema (“everyday system” or “vernacular system”Footnote 9). The bookish system is more or less the system we know from other documents from that time, including Church Slavic writing. The vernacular system deviates from the bookish system in a number of features, the most conspicuous being the interchangeability of the letters <о> and <ъ> and <е> and <ь> (Zaliznjak 2002, 2004, pp. 21–28). There is no clearcut divide between the systems, and the choice of one or the other system is neither user nor usage oriented. The two systems do not correspond to the category of document, its contents, or the social characteristics of the authors (Bunčić, 2016, p. 136).Footnote 10 Birch barks showing the vernacular system are attested from the very beginning of birch-bark writing but were at first greatly outnumbered by documents that used the bookish system. The 12th century saw a steady rise of vernacular orthography, in the 14th century it subsided again. The emergence of vernacular spelling does very likely not have a phonemic / phonetic background but is, as suggested by Zaliznjak, linked to the pronunciation of Church Slavic texts when read out loud. The ecclesiastical pronunciation practice read out the graphemes representing the jer vowels <ъ> and <ь> as [o] and [e] regardless of their actual value. This was also practiced in the teaching of how to read. If there was no systematic teaching of how to write the resulting quasi-equivalence of the graphemes <o> and <ъ> and <e> and <ь> would then have been transferred to the process of writing (Zaliznjak, 1986, pp. 104–105; 2002, pp. 597–602).Footnote 11 Dekker (2018b, pp. 183–187) tries to align the two orthographic systems with the orality: literacy contrast and comes to a “paradoxical appraisal” (Dekker, 2018b, p. 187). On the one hand, the lack of uniformity in the vernacular system is a feature of orality, on the other hand, its origin in the context of and based on ecclesiastical reading practices and the subsequent deviation from the (assumed) vernacular pronunciation makes it a feature of literacy.Footnote 12 Taking the argument a step further, one could come to the conclusion that at least the rise of vernacular spelling is a movement away from the Church Slavic model, i.e., away from literacy. The reasons for its decline must then be sought elsewhere. It could be an overall adaptation to Muscovy writing practices (Bunčić, 2016, p. 134) or, as Zaliznjak suggests, a change in ecclesiastical pronunciation towards a more natural reading («замен[а] прежнего искусственного произношения реальным», 2002, p. 611).

The development that seems to become manifest in the diachrony of the opening and closing formulae and, possibly, in the rise of vernacular orthography, has not gone unnoticed. Worth (1984, p. 330) calls it “Russification” or “de-Slavonification”, Fakkani [Faccani] (2003, p. 228) sees an «освобождение письменности от ее ‘сакральности’» (“a liberation of writing from its ‘sacredness’”) and an “emancipation” of vernacular writing («эмансипаци[я] письма отражающего живую речь определенного социума»). Gippius notes a “vulgarisation of writing habits” in connection with the “outburst of ‘everyday’ orthography” and the “steady abandonment of Church Slavonic formulas of salutation as well as of the initial cross” (Gippius, 2012, p. 249).

In the following sections I will analyze the development of selected linguistic features that could have a bearing on the degree of orality or literacy of a text and are typical for the bookish or the non-bookish registers. The choice is to a certain degree random and partly determined by the possibility of conducting an efficient corpus search in the birch-bark supcorpus of the Russian National CorpusFootnote 13 for the relevant features.

5 The diachronic development of orality and literacy: selected features

5.1 Use of function words

5.1.1

Iže

Iže

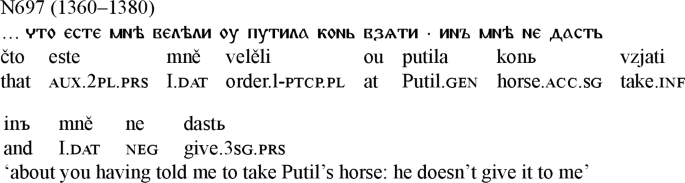

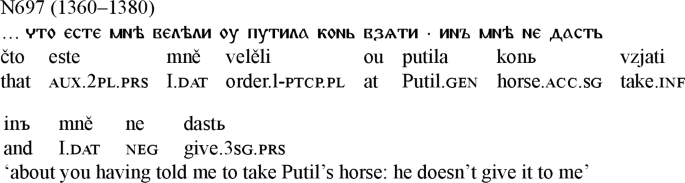

The use of the relative pronoun iže and its variants is typical for Church Slavic literacy. The Old East Slavic vernacular employs mostly pronouns based on čto, or in later periods, kotoryj (cf. Borkovskij, 1958, pp. 112–146; for relative words in the birch-bark corpus see Mendoza, 2007). The bookish pronoun iže is, however, attested in the birchbark documents. There are five occurrences of iže and seven occurrences of iže to. Table 1 lists the birch barks that contain iže (to) and shows that almost all of them are early documents (12th c.) The only attestations from a later period (1360–1380) are the occurrences of ježe in N948 and N266. Note that the function of iže is not always necessarily that of a relative pronoun. This is particularly true for the form ježe. In N266 it could be a either conjunction or a pronoun,Footnote 14 in N266 it is part of the expression ježe denь ‘every day’.

5.1.2

Jako

Jako

The connective word jako (to) ʻhowʼ, ʻthatʼ, ‘if’, ‘when’ is also typical for the bookish style. It is attested five times in the birch-bark documents,Footnote 15 all of them dating from the 12th century. Table 2 shows the occurrences of jako with context.

5.1.3 The form ničto že in genitive position

In Church Slavic the form ničьto že, which looks like a nominative/accusative form, is regularly used in object position in negated sentences, a position that usually requires the genitive (Zaliznjak, 2004, pp. 159–160). The birch-bark documents show both ničьto že and the genitive form ničego že. We find four attestations of ničьto že in negated sentences in birch-bark documents form the 12th century and two occurrences of the genitive form ničego že from the 12th and 13th centuries. The attestations for both ničьto že (N109, N644, N9, possibly N924) and ničego že (N1045, N651) are listed in Table 3.

The uses of iže, jako, and ničьto že do not correspond to any particular style within the birch-bark documents. For example, N731 and N644 show dialect features, N9 uses standard orthography and morphology and the author/scribe of N752 obviously was familiar with the bookish register (Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 251) but employs vernacular orthography and Old Novgorodian forms.

Zaliznjak interprets the attestations of iže, jako and ničьto že in genitive position in the birch-bark documents as indications of their occurrence in the spoken language of that time (Zaliznjak, 2004, pp. 160, 301, 393). The disappearance of these expressions would then be a mere matter of language change, without any socio-linguistic implications. Given the fact that they abound in Church Slavic documents and given the developments “away from literacy” as described in Sect. 4.1, their disappearance from the birch-bark texts could, as a side effect, have been a manifestation of the emancipation from Church Slavic bookishness.

5.1.4 Formulaic se

The particle se ‘this, here’ has several functions. One of them is its formulaic use at the beginning of a document when it introduces an official act. Examples (1) and (2) show the formulaic use, whereas se in (3) is an attestation of “neutral” (Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 398) se (deictic reference to the birch bark):

-

(1)

-

(2)

-

(3)

Most of the documents with formulaic se occur in the category “official documents” (“officialʹnye dokumenty”Footnote 18), such as testaments or confirmations of business transactions; only very few belong to other categories.Footnote 19 Formulaic se is found in two environments. One is the formula se azъ ‘hereby I’ at the beginning of a testament, and the other one is formed by a context that includes the performative use of a past tense form, mostly an aorist (cf. below).

Formulaic se is a relatively new phenomenon in the birch-bark corpus. There are two attestations before the mid-13th century, only then they start to get more frequent, cf. Fig. 2.

The formula se azъ is well known from secular parchment documents. Its origin, however, is Church Slavic (Zoltán, 1987). The fact that formulaic se is only attested in younger birch barks could be witness to a different development from the one described so far, namely the adaptation of writing practices typical for official and administrative writing. Since formulaic se is basically restricted to official documents it should be interpreted in the context of the evolution of official writing on birch bark. Figure 3 shows that the chronological distribution of birch barks labeled “official documents” on DBG is very similar to the distribution of formulaic se. The low number of formulaic se and the official documents in the 12th century is particularly significant considering the high number of birch barks in this period.

Hence, the spread of formulaic se cannot be taken separately but has to be interpreted with regard to the increase of official documents on birch bark.Footnote 20 The rise of the latter enables the rise of formulaic se and together they are part of a development of birch-bark wiriting towards the model represented by non-bookish parchment documents.

5.2 Usage of tense forms

Unlike Church Slavic, non-bookish registers show only restricted usage of imperfect and aorist. It is still an open question when these tenses became obsolete in Old East Slavic. Some argue that they were fully functional up until the mid-13th century, others suggest that they disappeared from the vernacular as early as the 11th century. The usage of imperfect and aorist forms in non-bookish documents are then interpreted as a striving for bookishness.Footnote 21 Similar to the cases discussed above, the development of tense usage is possibly also a manifestation of the socio-linguistic process of the emancipation of birch bark literacy from Church Slavic bookishness.

5.2.1 Imperfect

With only six attestations the occurrence of imperfect forms is an “extraordinary rarity” (črezvyčajnaja redkostʹ; Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 142) in the birch-bark documents. All birch barks date from the late 11th–12th centuries with three attestations occurring in the same text, cf. Table 4.

There is one imperfect form attested in a Church Slavic birch bark ([bě]3sg.impf N930, 1400-1410). In addition, N510 (1120-1240) shows bьšь.3sg.impf as part of a pluperfect form (stalь bьšь; Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 470).

The interpretation of the chronological distribution depends on the assumptions on the disappearance of the imperfect from the vernacular language. If we assume that the imperfect was extant until the 13th century, then the distribution of the imperfect forms in the birch-bark documents is just a function of its eventual disappearance in Old East Slavic. If we presume that it was obsolete as early as the late 11th the imperfect forms are another manifestation of the influence of the bookish register on early birch-bark literacy.

5.2.2 Aorist

The aorist forms paint a different picture. Not only are they more frequent than imperfective forms, but they also occur in later documents and even become increasingly frequent in younger documents, cf. Fig. 4.Footnote 23

In addition to its temporal-aspectual function the aorist was used in a “performative” function (Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 175). A performatively used aorist flags the document as a concomitant or ratification of the performed act referred to in the message.Footnote 24 This usage was typical for official documents, cf. (1) above for illustration, here repeated as (4):

-

(4)

If we divide the aorist forms by function, the picture changes somewhat. As Fig. 5 shows, the temporal-aspectual use of the aorist is scattered across the centuries, while performative aorists forms do not appear until the late 13th century except for an early outlier from the early 12th century (ce posъlaxově N842, 1120–1140).Footnote 25

If we now look at some of the data from a qualitative point of view the chronological relation will shift a bit more. The peak of non-performative aorist forms in the period from 1320 to 1340 is caused by one single document, the birch bark N46:

-

(5)

This document is some kind of riddle or joke and consists of ready-made text chunks (Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 542). One could now argue and suggest that the aorist forms in N46 should not be considered in the Fig. 5. This would further reduce the number of non-performative aorist forms in the younger documents, cf. Fig. 6.

The performative aorist often occurs in incipits together with formulaic se, hence the distributions of se and the performative aorist are quite similar. Like formulaic se, the performative aorist is a marker for officiality, and its increase is very likely connected to the rise of official writing on birch bark.

5.3 Linkage of predicative units

5.3.1 Linking of active participle and finite clause

The extensive use of participles and the syntactic complexity that comes with it is a typical feature of the bookish register. The frequency of participles in the birch-bark documents is much lower and their morphological and syntactic potential is restricted (Živov, 2017, pp. 330, 456-457, and passim). According to Zaliznjak, long form participles and short form participles in oblique cases behave like adjectives. Active participles that only inflect for number and gender are used in a converb-like function (Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 134; 2004, pp. 184–185). It is the latter function that will play a role in this section.

A well-known feature of both Church Slavic and Old East Slavic syntax is the linking of participle and finite clause by a connective element (a, i, da, and othersFootnote 26), especially when the participle comes before the finite clause. See the following examples for illustration. In (6) the participle precedes the finite clause and (7) shows the reverse order:

-

(6)

-

(7)

The ratio of active participles in relation to the overall number of birch-bark documents remains relatively stable across the centuries, see Fig. 7 and compare it with the chronological distribution of the birch barks as shown in Fig. 1.

However, there are noticeable changes in the way participle and finite unit are connected. Figure 8 represents the chronological distribution of participle-constructions with and without a connective element between participle and finite clause, regardless of their relative position.Footnote 27 The asyndetic type (w/o conn) becomes relatively more frequent over time whereas the relative number of the syndetic type (w conn) declines.Footnote 28

If we look at constructions with pre-posed participles and those with post-posed participles separately, the pictures changes. Post-posed participles generally prefer linkage without a connective element while the syndetic type is consistently infrequent, cf. Fig. 9.

Constructions with pre-posed participles are not as stable. We observe a decline of constructions with syndetic linking and a rise of constructions without connective element, see Fig. 10. Hence, the change of the relationship between asyndetic and syndetic constructions observed in Fig. 8 is mostly due to constructions with pre-posed participles.

Even though the use of a connective between participle unit and finite unit occurs in both bookish and non-bookish documents it is more a non-bookish than a bookish phenomenon (Larsen, 2001, p. 188; Živov, 2017, pp. 378, 454). Moreover, the ratio of syndetic and asyndetic linkage varies not only across registers but also across genres. Whereas birch-bark documents generally prefer syndetic to asynetic linking, non-bookish parchment documents show the opposite behavior (Živov, 2017, pp. 378, 389–390). Živov attributes this to their “higher status” and “stronger orientation toward the bookish texts”.Footnote 29 Hybrid texts, such as chronicles, exhibit a more heterogeneous picture (Živov, 2017, pp. 435–449).

Constructions with a connective element between active participle and finite verb and the way they are connected have been discussed from the perspective of the participle’s syntactic autonomy, the syntactic relation between finite verb and participle, and the “coordinating” or “subordinating” status of the connective element (for a summary and critical review of the discussion see Živov, 2017, pp. 435–438). Since the concepts of syntactic dependency, subordination, and coordination are not yet sufficiently defined when it comes to older linguistic stages it is difficult to interpret the development in birch-bark literacy in terms of universal features of literacy/orality, e.g., as an expansion of syntactic complexity. More promising is an explanation that reads the increase of asyndetic constructions as an adaptation to a certain model of writing. Since the intertextual link between birch-bark writing and official writing has already been established (see Secs. 5.1.4 and 5.2.2) I would argue that the model in this case is official writing rather than Church Slavic bookishness.

5.3.2 Linking of finite clauses

The choice between syndetic and asyndetic linking is also relevant when it comes to the combination of clauses with finite verbs. In Old East Slavic we often find structures like (8) and (9):

-

(8)

-

(9)

This type of clause combination is usually referred to as the connection of a preceding subordinate clause and a following main clause by a coordinative conjunction.Footnote 30 This paradoxical formulation once more reveals the difficulties we face when we transfer categories that might be fitting for modern languages to older stages. The dependency relation between the clauses and the characterization of the connective seem to have been classified by comparing the Old East Slavic structures to their corresponding structures in Modern Russian rather than by taking the older data at face value.

If we try and describe the data presented by the birch-bark documents without preconceived notions about syntactic categorization we realize that the difficulties run even deeper. Since there is no punctuation that separates clauses or sentences it is not always clear whether a sequence of two (or more) predicative units forms a higher, complex structure or whether we deal with a mere concatenation of units without any internal hierarchy. This is particularly true when it comes to predicative units preceded by the element a. A is highly frequent at the beginning of a predicative unit, cf. ex. (10), where it introduces almost every unit:

-

(10)

N109 (1100–1120)

gramota : otъ žiznomira : kъ mikoule : koupilъ esi : robou: plъskove : a nyne mja : vъ tomъ : jala kъnjagyni : a nyne sja drou=žina : po mja poroučila : a nyne ka : posъ=li kъ tomou : mouževi : gramotou : eli ou nego roba : a se ti xočou : kone koupi=vъ : i kъnjažъ moužъ vъsadivъ : ta na sъ=vody : a ty atče esi ne vъzalъ kounъ : texъ : a ne emli : ničъto že ou nego :

‘a gramota from Žiznomir to Mikula. You bought a female slave in Pskov, and now the princess arrested me for this, and now the retinue vouched for me, and now send a gramota to that man: does he have the slave? and I want this: after having bought horses and having mounted one of the prince’s man then to the hearing, and you, if you haven’taken that money and don‘t take anything from him’

We even find a at the very beginning of a birch-bark document, see example (11) that shows the use of a before an opening formula (incidentally, a also precedes the closing formula):Footnote 31

-

(11)

N501 (1320-1340)

a poklono ot nekefa ko maruku podo[b]oro [p]o[je]ni po rozmeri [i] me=ne jeni a jaza tobe kolone=jusja

‘and a bow from Nekef to Mark take the “podbor”Footnote 32 in the right size and take [one] for me and I bow to you’

In these and many other examples the element a serves as a device that separates discourse units. This may happen on different levels, on the macro level (constituent elements of the message, (11)) or on a lower level (separation of content units, (10)). Hence a obviously operates on the discourse rather than the syntactic level.

In order to gather a sufficient number of clause combinations (as opposed to mere concatenations) I searched the birch-bark subcorpus of the Russian National Corpus for all conjunctionsFootnote 33) exept for a and i, and for relative words. I then manually selected the examples that were in preposition and checked for syndetic and asyndetic linking of the following clause. This method did not detect combined structures whose first unit is introduced by a or i or is not introduced by a connective at all, but it yielded enough material for a diachronic comparison. For lack of a better term I call these structures “correlative structures”, even though there is obviously no correlative element with asyndetic linkage.

Figure 11 displays the development of asyndetic and syndetic linking across the centuries. It shows that the structures without connective caught up or even outnumbered the attestations with connective in the late 12th century.

The connectives preceding the second unit vary greatly in frequency and across time. The element a is the most numerous by far (72 out of 124 instances), i does not appear until 1300 (nine attestations), da occcurs until the mid-13th century (six times), to appears 20 times scattered across the centuries, ino is attested for the first time in the 1380–1400 period and occurs only four times. In addition, there are a few instances of other connectives and combinations of connectives.

Syndetic linkage is common in non-bookish documents and does not seem to be a bookish feature. Even though it does occur in Old Church Slavic (Večerka, 2002, 360–362) and in East Slavic bookish documents (Pičxadze, 1999, p. 30), it is apparently the exception rather than the rule. In addition, in the bookish registers the connective element is usually to, not a or i (Pičxadze, 1999, p. 30; Borkovskij, 1973, p. 163). The interpretation of the chronological distribution of syndetic and asyndetic linking in correlative structures in the birch-bark texts is not easy for the time being, since I do not possess enough data on these constructions in bookish texts and non-bookish parchment documents. The relative increase of asyndetic constructions could be an indication that the connectives, especially a lose their discourse structuring function and become a syntactic device. This, in turn, could be interpreted as an increase of literacy, since the frequent use of discourse structuring signals is a universal feature of orality (Koch & Oesterreicher, 1986, p. 27). However, for a full account of this trajectory we need an analysis of the use of said connectives outside correlative structures.

6 Conclusion

The features I discussed changed over time in quantity or quality or both. The changes give rise to the following hypothesis: the socio-linguistic and pragmatic development of birch-bark literacy was multi-dimensional. While some changes lead away from the Church Slavic model, others point to an increasing impact of non-bookish parchment documents on birch-bark literacy.

The changes that most clearly indicate an “emancipation” of writing on birch bark from Church Slavic literacy are the changes of address formulae (disappearence of Church Slavic forms, spread of East Slavic poklonъ) and, possibly, in the dominance of the vernacular script in the 12th–13th centuries. In addition, one can observe the disappearance of typically bookish forms and expressions, such as the relative pronoun iže, the connective jako, the form ničьto že in negated sentences, the imperfect and the non-performative aorist. This development is compatible with the trend to less bookishness, if not a manifestation of it.

Another group of changes can be read as an adaption of linguistic practices typical for official writing. It includes the rise of official documents and the characteristic features that go with them, such as the formulaic use of se and the performative aorist. It seems that the registers of non-bookish parchment documents had a growing impact on birch-bark literacy and replaced Church Slavic as a model.

The diachronic changes of clause linkage could be interpreted in a similar vein. This holds in particular for constructions with pre-posed participles. Early birch-bark documents strongly prefer the introduction of the finite predicative unit by a connective element whereas the asyndetic type does not gain ground until the late 13th century. The dominance of syndetic linking sets birch-bark writing apart from both bookish documents and non-bookish documents on parchment.

With regard to the literacy-orality continuum the replacement of one model by the other must be interpreted on two levels. On the “global” level the abandonment of the Church Slavic model means a loss of literacy since Church Slavic writing represents the highest degree of literacy. On the level of individual changes, however, there may be movements away from orality, such as the increase of the asyndetic linking of participles.

Correlative structures are even more difficult to construe in terms of literacy and orality. In the analyzed material the syndetic type prevails, especially until the 13th century. Asyndetic linking then slowly increases. I had little data on bookish and non-bookish parchment documents, so the relation to a potential model structure in other registers or genres was difficult to gauge. In addition, correlative structures have to be looked at in a broader context that includes all types of clause combining and concatenation. On a preliminary basis I suggest to interpret the connectives in question, in particular the connective a as being in a process of transition from a discourse structuring element to a syntactic device. This, in turn, may be read as the loss of a universal feature of orality. Ultimately, that could also be true for the linking of participles.

Concluding, I want to stress the fact that these results are highly tentative, since the numbers we are dealing with are very small, often in the single digits. For corroborating them we need more data on features that have a bearing on the orality vs. literacy and bookishness vs. non-bookishness contrasts and compare them with Church Slavic and non-bookish documents on parchment (legal texts, treaties, private deeds, cf. Živov, 2017, 212).

Notes

The terms “literacy” and “orality” translate Koch and Oesterreicher’s concepts Schriftlichkeit and Mündlichkeit (Koch & Oesterreicher, 1986). See also Franklin (2002, p. 4) on the meaning of the terms “orality” and “literacy”: “In cultural history ‘literacy’ has acquired a third meaning: it denotes the sum of social and cultural phenomena associated with the uses of writing (here the notional opposite of ‘literacy’ is ’orality’).”

For details and references see Sect. 4.1.

The script of the Gnezdovo inscription, the most powerful argument for the theory of pre-Christian literacy, could be either Cyrillic or Greek. If the latter were the case the inscription would be “a monument of Bulgarian rather than of East Slavonic epigraphy” (Gippius, 2012, pp. 228–229).

This number does not include the 15 birch barks from the 2022 excavations, which have not been published yet. They were presented by A.A. Gippius in the traditional annual lecture on November 11, 2022, available on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EYtoonQ1hTk&t=1261s. See also Dmitrij Sičinava’s presentation on https://arzamas.academy/mag/1160-beresta22 (Sičinava, 2022; both sites accessed February 10, 2023).

See Schaeken (2019, pp. 27–32) for a detailed chronology and possible reasons for this distribution.

N=Novgorod.

36 out of 39 occurrences of poklanjanie and all instances of tsěluju tja in Gippius’s material are attestations from the pre-Mongol period (Gippius, 2012, p. 248). The latest occurrence of poklanjanie occurs in N615 (1280–1300), poklonъ appears for the first time in Staraja Russa 31 (1180–1200) and is very frequent in the late 13th century.

I will henceforth use the term “vernacular system”, suggested by Bunčić (2016).

We also find traces of the vernacular system in parchment documents (e.g., the treaty of Smolensk with Riga and Gotland) and graffiti, and sometimes even in bookish texts, cf. Zaliznjak (2002, p. 577).

An insightful and elaborate explanation is offered by Petruxin (2020). He convincingly argues that, in addition to the ecclesiastical pronunciation, the teaching and learning practice of “reading by syllables” (čtenie po skladam) played an integral role in the emergence of the verncular system.

This view finds support in Petruxin’s assessment of the vernacular spelling as a certain kind of alphabetical-syllabic system, whose emergence represents a step backwards in the evolution of writing systems (Petruxin, 2020, p. 123–125).

For obvious reasons, I did not include the Church Slavic birch barks in my analysis, but I will refer to them for comparison.

… [je]že bude[š]e ne otda=(l)… ‘if you don’t give (it) away…’

… [je]že bude[š]e ne otda=(l)… ‘if you don’t give (it) away…’In the Church Slavic birch barks jako is quite frequent.

N924 is only a fragment and the reading is mostly conjecture (Zaliznjak, 2004, pp. 520, 766).

The letter

is damaged, it could also be a

is damaged, it could also be a  (Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 444), which would make it another instance of ničьto že.

(Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 444), which would make it another instance of ničьto že.See Zaliznjak (2004, p. 20) and DBG for the categorization of birch-bark documents in terms of contents.

Private letter (N842) and label (N309).

Cf. Živov (2017, pp. 608–618) for discussion and Zaliznjak (2004, pp. 173–175) on the use of imperfect and aorist in the birch-bark documents. Based on the difference between the chronicles, where aorist and imperfect were fully functional until the 14th century, and the birch-bark documents, where the perfect functioned as the general past tense, while the simple preterits did not have a specific semantic load, Zaliznjak argues that the aorist was transferred form active usage to passive knowledge in the 12th century. He further assumes that the development of the imperfect, which is attested only a few times, took a similar course (Zaliznjak, 2004, pp. 173–174).

There is one imperfect form attested in a Church Slavic birch bark ([bě]3sg.impf N930, 1400-1410). In addition, N510 (1120-1240) shows bьšь.3sg.impf as part of a pluperfect form (stalь bьšь; Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 470).

In addition to the forms used for Fig. 4 there are two more potential aorist forms: vъda and vosprosi. The form vъda (N1050, 1100–1120) could be either an aorist or a present tense form (Janin & Zaliznjak, 2015, p. 151) and for vosprosi (N755, 1420–1430) an aorist, present tense or even imperative reading is possible (Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 637). The Church Slavic birch barks also contain several aorist forms (N419, 1280–1300 with two attestations, N727, 1180–1200 with twelve attestations, N916, 1280–1300 with two attestations and N930, 1400–1410 with five).

Two forms did not go into Fig. 5, since their function could not be determined due to the lack of legible context (sta and (po)slaxomъ in N137, 1300-1320).

The numbers do not add up to the total number of active participles, since in many cases it is not possible to determine the position of the participle or the type of linkage due to damages to the birch bark.

«это, надо думать, связано с более высоким статусом пергаменных грамот и соотнесенной с этим статусом большей ориентацией на книжные тексты» (Živov, 2017, p. 390).

See for example, Zaliznjak (2004, p. 191): «Как известно, в древнерусском, в отличие от современного русского, в сложноподчиненном предложением главное предложение молго соединиться с препозитивным придаточным (относительным, условным или обстоятельным) с помощью сочинительного союза» (“It is known that in Old Russian, unlike Modern Russian, in complex sentences the main clause may be connected to the preceding subordinating clause (relative, conditional, or adverbial) by a coordination conjunction”).

According to Zaliznjak (2004, p. 299), the use of a at the beginning of a birch-bark letter is a «явная черта народного синтаксиса» (“clear feature of vernacular syntax”).

The meaning of podborъ is not completely clear in this context (Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 559).

I.e., lexemes classified as “sojuzy” in Zaliznjak (2004).

References

Borkovskij, V. I. (1958). Sintaksis drevnerusskix gramot. Moskva: Izdatelʹstvo Akademii Nauk SSSR.

Borkovskij, V. I. (1973). Sravnitel’no-istoričeskij sintaksis vostočnoslavjanskix jazykov. Složnopodčinennye predloženija. Moskva: Nauka.

Bunčić, D. (2016). Thirteenth-century Novgorod: medial diorthographia. In D. Bunčić, S. L. Lippert, A. Rabus, & A. Antipova (Eds.), Biscriptality. A sociolinguistic typology (pp. 129–139). Heidelberg: Winter.

Dekker, S. (2014). Communicative heterogeneity in Novgorod birchbark letters: a case study into the use of imperative subjects. In E. Fortuin (Ed.), Dutch contributions to the Fifteenth International Congress of Slavists (pp. 1–23). Leiden: Brill.

Dekker, S. (2018a). Old Russian birchbark letters. A pragmatic approach. Leiden: Brill.

Dekker, S. (2018b). Three dimensions of proximity and distance in the Old Russian birchbark letters. In A. Kapetanović (Ed.), The oldest linguistic attestations and texts in the Slavic languages (pp. 176–190). Vienna: Holzhausen.

Dekker, S. (2022). Past tense usage in Old Russian performative formulae. A case study into the development of a written language of distance. In I. Mendoza & S. Birzer (Eds.), Diachronic Slavonic syntax: traces of Latin, Greek and Church Slavonic in Slavonic syntax (pp. 179–198). Berlin, Boston: Mouton de Gruyter.

DBG = Drevnerusskie berestjanye gramoty. gramoty.ru (accessed March 3, 2023).

Fakkani [Faccani], R. (2003). Nektotorye razmyšlenija ob istokax drevnenovgorodskoj pisʹmennosti. In V. L. Janin, A. A. Gippius, A. A. Zaliznjak, E. A. Rybina, & J. Schaeken (Eds.), Berestjanye gramoty: 50 let otkrytija i izučenija (pp. 224–234). Moskva: Indrik.

Franklin, S. (2002). Writing, society and culture in early Rus, c. 950–1300. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gimon, T. V. (2015). Letopisanie i razvitie pisʹmennoj kul’tury (Novgorod, XI–pervaja polovina XII v.). Slověne, 4, 94–110.

Gimon, T. V. (2016). Razvitie delovoj pisʹmennosti v Novgorode v XI–XIV vv. Vostočnaja Evropa v drevnosti i srednevekovʹe, 28, 72–78.

Gippius, A. (2012). Birchbark literacy and the rise of written communication in Early Rusʹ. In K. Zilmer & J. Jesch (Eds.), Epigraphic literacy and Christian identity. Modes of written discourse in the newly Christian European North (pp. 225–251). Turnhout: Brepols.

Gippius, A. A. (2004). K pragmatike i kommunikativnoj organizacii berestjanych gramot. In V. L. Janin, A. A. Zaliznjak, & A. A. Gippius (Eds.), Novgorodskie gramoty na bereste. Iz raskopok 1997–2000 gg. (pp. 183–232). Moskva: Russkie slovari.

Gippius, A. A. (2009). Nabljudenija nad ėtiketnymi formulami berestjanyx pisem. In L. L. Fedorova (Ed.), Stereotipy v jazyke, kommunikacii i kulʹture (pp. 279–300). Moskva: RGGU.

Gippius, A. A. (2019). Berestjanye gramoty iz raskopok 2018 g. v Velikom Novgorode i Staroj Russe. Voprosy Jazykoznanija, 2019(4), 47–71.

Janin, V. L., & Zaliznjak, A. A. (2015). Novgorodskie gramoty na bereste No. 916-1063. In V. L. Janin, A. A. Zaliznjak, & A. A. Gippius (Eds.), Novgorodskie gramoty na bereste. Iz raskopok 2001–2004 gg. (pp. 12–165). Moskva: Izdatelʹstvo Akademii nauk SSSR.

Koch, P. (1985). Gesprochenes Italienisch und sprechsprachliche Universalien. In G. Holtus & E. Radtke (Eds.), Gesprochenes Italienisch in Geschichte und Gegenwart (pp. 42–76). Tübingen: Narr.

Koch, P., & Oesterreicher, W. (1986). Sprache der Nähe – Sprache der Distanz. Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit im Spannungsfeld von Sprachtheorie und Sprachgeschichte. Romanistisches Jahrbuch, 36, 15–43.

Koch, P., & Oesterreicher, W. (1994). Schriftlichkeit und Sprache. In H. Günther & O. Ludwig (Eds.), Schrift und Schriftlichkeit (pp. 587–604). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Larsen, K. (2001). The correlation between *tj-Reflex and syntax (based on forms of the present active participle in “Boпpaшaниe киpикa” and “Пoучeниe влaдимиpa мoнoмaxa”)’. Russian Linguistics, 25, 183–207.

Lazar, M. (2014). Von Geld und guten Worten. Entwicklung des russischen Geschäftsbriefes als Textsorte. München: Sagner.

Mendoza, I. (2007). Relativsätze in den Birkenrindensätzen. In U. Junghanns (Ed.), Linguistische Beiträge zur Slavistik XIII (pp. 49–62). München: Sagner.

Mendoza, I. (2016). Alltagssprache, Alltagswelt. Die russischen Birkenrindentexte zwischen Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit. In A. K. Bleuler (Ed.), Welterfahrung und Welterschließung in Mittelalter und Früher Neuzeit (pp. 117–133). Heidelberg: Winter.

Mendoza, I. (2017). The Novgorod birch-bark manuscripts. Manuscript Cultures, 10, 145–159.

Petruxin, P. P. (2020). Čtenie po skladam i grafiko-orfografičeskie osobennosti drevnerusskix berestjanyx gramot. Slověne, 9, 103–128.

Pičxadze, A. A. (1999). O značenijax i funkcijax sojuza a v drevnerusskom jazyke. In S. I. Gindin & N. N. Rozanova (Eds.), Jazyk, kulʹtura, gumanitarnoe znanie. Naučnoe nasledie G. O. Vinokura i sovremennostʹ (pp. 28–37). Moskva: Naučnyj mir.

Russian National Corpus (Nacionalʹnyj korpus russkogo jazyka). https://ruscorpora.ru/ (accessed February 20, 2023).

Schaeken, J. (2011). Don’t shoot the messenger. A pragmaphilological approach to birchbark letter no. 497 from Novgorod. Russian Linguistics, 35, 1–11.

Schaeken, J. (2014). Don’t shot the messenger: part two. In E. Fortuin (Ed.), Dutch contributions to the fifteenth international congress of slavists (pp. 155–166). Leiden: Brill.

Schaeken, J. (2019). Voices on birchbark. Everyday communication in medieval Russia. Leiden: Brill.

Sičinava, D. V. (2022). Berestjanye gramoty – 2022: deti v založnikax u knjazja i denʹgi nad pečkoj. https://arzamas.academy/mag/1160-beresta22 (accessed February 10, 2023)

Večerka, R. (2002). Altkirchenslavische (altbulgarische) Syntax, IV. Die Satztypen: der zusammengesetzte Satz. Freiburg i. Br.: Weiher.

Worth, D. (1984). Incipits in the Novgorod birchbark letters. In M. Halle (Ed.), Semiosis. Semiotics and the history of culture: in honorem Georgii Lotman (pp. 320–332). Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Zaliznjak, A. A. (1986). Novgorodskie berestjanye gramoty s lingvističeskoj točki zrenija. In V. L. Janin (Ed.), Novgorodskie gramoty na bereste. Iz razkopok 1977–1983 gg. (pp. 89–219). Moskva: Nauka.

Zaliznjak, A. A. (1987). Tekstovaja struktura drevnerusskix pisem na bereste. In T. V. Civʹjan (Ed.), Issledovanija po strukture teksta (pp. 147–182). Moskva: Nauka.

Zaliznjak, A. A. (2002). Drevnerusskaja grafika so smešeniem ъ - о i ь - е. In A. A. Zaliznjak (Ed.), “Russkoe imennoe slovoizmenenie” s priloženiem izbrannyx rabot po sovremennomu russkomu jazyku i obščemu jazykoznaniju (pp. 577–612). Moskva: Jazyki slavjanskoj kulʹtury.

Zaliznjak, A. A. (2004). Drevnenovgorodskij dialekt. Vtoroe izdanie, pererabotannoe s učetom materiala naxodok 1995–2003 gg. Moskva: Jazyki slavjanskoj kulʹtury.

Živov, V. M. (2017). Istorija jazyka russkoj pisʹmennosti. Moskva: Universitet Dmitrija Požarskogo.

Zoltán, A. (1987). ‘SE AZЪ … K voprosu o proisxoždenii načalʹnoj formuly drevnerusskix gramot. Russian Linguistics, 11, 179–186.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Paris Lodron University of Salzburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mendoza, I. Old East Slavic birch-bark literacy – a history of linguistic emancipation?. Russ Linguist 47, 343–365 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-023-09278-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-023-09278-9

Iže

Iže

Jako

Jako

… [je]že bude[š]e ne otda=(l)… ‘if you don’t give (it) away…’

… [je]že bude[š]e ne otda=(l)… ‘if you don’t give (it) away…’ is damaged, it could also be a

is damaged, it could also be a  (Zaliznjak,

(Zaliznjak,