Abstract

In this study, we use the General Regionally Annotated Corpus of Ukrainian (GRAC, www.uacorpus.org) as an experimental field for testing stylometric approaches for variationist analysis. While, in the last years, quantitative methods such as binomial mixed-effects regression models as well as machine-learning methods such as random forests have gained considerable popularity in corpus linguistics, methods from stylometry have not been used for variation-linguistic analysis very often. Using data from GRAC, we show that a stylometric approach can be useful to analyze the diachronic development of Standard Ukrainian in the 20th century. We take departure from the two main variants of Standard Ukrainian used in the interwar period in Soviet Ukraine, on the one hand, and Western Ukraine as it was part of the Polish republic, on the other. We ask: what can stylometry tell us about how these standards differed and about their subsequent fate in enlarged Soviet Ukraine after WWII?

Our analysis shows that certain specifically Western Ukrainian features common during the first decades of the 20th century did not find their way into the post-WWII standard, while others were retained. Moreover, we show that, by and large, stylometry shows a stronger continuity of the Eastern than the Western standard.

Methodologically, we demonstrate that stylometry can be used as a tool to start corpus-linguistic research from a bird’s-eye view and in an inductive manner, without formulating any hypotheses regarding particular variables, and later zoom in on hitherto unknown variables representing regional or diachronic differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Ukrainian has an exceptionally complex history (Shevelov, 1979; Moser, 2016). Based on Central Ukrainian dialects, it first thrived in Austrian-governed Western Ukraine, namely Galicia, where it was in a multilingual setting with strong Polish and German influence. Here, it acquired important functions and registers and was widely used in schools and some higher education. During this period, the conditions for a Standard Ukrainian language in Central and Eastern Ukraine, then part of imperial Russia, were much worse; the printing of Ukrainian books was banned and Ukrainian only acquired some recognition for a short period after 1905. This situation reversed in the interwar period, when Western Ukraine became part of newly reestablished Poland, while Central and Eastern Ukraine eventually formed the Ukrainian Soviet Republic as part of the USSR. As a result of these divergent developments, two standard variants of Ukrainian developed that were both based on the same Central Ukrainian dialects, but differed in many other details, including orthography, lexicon, and morphology (Shevelov, 1966).

It was only after the Second World War that these pluricentric variants effectively merged into a new Soviet Standard Ukrainian. However, many details of these developments are unclear. While some scholars take the view that the norm of postwar Soviet Ukrainian can be exhaustively described as artificial russification of the standard (which, without doubt, was part of the program), other scholars stress that both Western and Eastern elements found their way into the standard. Ultimately, notwithstanding work on individual phenomena and developments, due to the lack of suitable and comprehensive corpus data, these developments have not been empirically analyzed and are still not well understood.

This paper makes an empirical contribution to the study of the differences between the Standard Ukrainian written before WWII in Western Ukraine, on the one hand, and Central and Eastern Ukraine, on the other, and how these differences diminished after WWII.

We use data from the General Regionally Annotated Corpus of Ukrainian (GRAC, Shvedova et al., 2017–2022), the largest and most comprehensive reference corpus of Ukrainian to date. We use a selection of novels by authors from Lviv, on the one hand, and Kyiv, on the other, written in two time periods before and after WWII. We thus base our analysis on four text samples broadly representing Western and Eastern Standard Ukrainian before and after 1945.Footnote 1

Methodologically building on von Waldenfels and Eder (2016), we use stylometry as implemented in the R (R Core Team, 2022) package stylo (Eder et al., 2016) to approach the differences between these sets of texts.

Stylometry is an approach to the study of register and linguistic styles that relies on taking measurements by counting linguistic features. Linguistic features in this sense refers to a wide range of possible linguistic elements ranging from letters, grammatical categories such as parts of speech (Stamatatos, 2009), to punctuation. The most widespread approach, introduced by Mosteller & Wallace (2007 [1964]) and used in this study, is the use of the most frequent word forms as features; these are overwhelmingly synsemantic words such as English I, is, or it. The frequencies of these features (in our case: of word forms) are determined and then taken as the input for computational methods that distribute texts into different groups or clusters.

Perhaps surprisingly, this rather simplistic approach has been successfully used to distinguish texts from different authors; thus, the method was used for author identification (Eder, 2011), i.e., variation in individual style. Numerous other use cases are possible; for example, stylometry has been used for studying diachronic variation (Górski et al., 2019).

Here, we use this method to investigate different regional variants of the same standard language. We show that Standard Ukrainian texts from Western and Eastern Ukraine written in the pre-WWII period neatly divide into two groups, thus showing that there are significant linguistic differences between these two variants. After the war, in contrast, the division between East and West became blurred, as did the divisions between the prewar and postwar samples of the same variant. We argue that the results of these experiments show that the emerging postwar variant is neither a straightforward continuation of the Eastern or the Western variant, but in fact a merged variety that has elements of both variants, even if the discontinuity is stronger in the West than in the East.

The stylo package allows us, in a further step, to pinpoint those word forms that most contribute to the groupings we are interested in. We use this feature to systematically and empirically investigate the difference between the Eastern and Western prewar variants. We show that this approach yields interesting results that empirically replicate well-known East-West contrasts such as the variant prepositions од vs. від ‘from’, thus confirming the validity of the method. Moreover, the approach also yields contrasts that have hitherto gone largely unnoticed, presumably because they are of a more probabilistic nature and thus less susceptible to qualitative research: for instance, we show that in the Western group, usage of би instead of abbreviated б is more frequent than in the Eastern texts. Note that from the point of view of Labovian sociolinguistics differences between variants are seldom clear-cut, but normally gradual. We argue that our inductive approach is thus able to reveal significant contrasts that are necessarily overlooked in less quantitative approaches.

Our paper is structured as follows: In Sect. 2, we give a brief introduction to GRAC and how it can be used for research in variationist linguistics. The main Sect. 3 is devoted to our empirical analysis using methods from stylometry, and the discussion of the results obtained, followed by a conclusion.

2 Brief introduction to GRAC

The General Regionally Annotated Corpus of Ukrainian (GRAC, Shvedova et al., 2017–2022) is a large reference corpus of Standard Ukrainian that comprises, at the moment of writing, almost 900 mio tokens of text, making it the largest curatedFootnote 2 reference corpus of Ukrainian today. It is developed by a network of people and institutions, see www.uacorpus.org for up-to-date references. GRAC is POS-tagged, lemmatized (without disambiguation) and semantically tagged (Starko, 2021). GRAC is a panchronic corpus that includes texts ranging from the end of the 18th century up to the 2020s. What sets GRAC apart from other corpora is its regional annotation (Shvedova & von Waldenfels, 2021). Over 80% of the corpus is annotated for one or more regions, understood either as the places of the biography of authors, or, in the case of newspapers and periodicals, the place of publication. This feature is indispensable for research into Ukrainian due to its complicated history of standardization.

GRAC has been successfully used for a number of empirical studies investigating variation and change in Standard Ukrainian (e.g., Rabus & Švedova, 2021; Lotoc’ka, 2021; Taran & Lebedenko, 2021, see also http://uacorpus.org/Kyiv/ua/doslidzhennya-na-osnovi-grak). Using stylometry on raw data taken from GRAC opens up new directions of research with that kind of corpus data.

3 Using stylometric methods for variation-linguistic analysis

3.1 Data and methodology

In order to get a reliable and representative dataset for stylometric analysis, we selected authors from two different regions and two different time periods each. The data from the western region predominantly consists of texts from Lviv, while the data from the central region predominantly consists of texts from Kyiv.

Table 1 shows the overall size of the subcorpora (authors, texts and tokens).

Note that the prewar texts represented in the corpus have been included in the form in which they were republished after WWII, and thus in postwar orthography. Differences in orthography that would have existed between the Western and the Eastern standard before the war and that could have distorted the results obtained are thus not relevant in our study.

As mentioned above, we used the stylo package (Eder et al., 2016) as well as ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016) for visualization, ggsignif (Ahlmann-Eltze & Patil, 2021) for the visualization of statistical significance, and RStudio (RStudio Team, 2022) as an integrated desktop environment. In order to obtain comparable results, we used stylo’s classification function with the settings MFW 500 meaning that incrementally the 500 most frequent words have been taken into account by the algorithm.Footnote 3 Additionally, we avoided tell-tale author- or genre-specific words by eliminating words that do not appear in the majority of the texts. We set culling to 70, meaning that only words have been taken into account that occur in more than 70 percent of the texts, making our clustering more robust and making it possible to highlight actual structural differences and not merely lexical idiosyncrasies. Moreover, we used Eder’s delta, as this is a distance measure that works well with highly inflected languages such as Ukrainian (Eder, 2015). As compared to Burrows’ (2002) delta, the ‘classical’ delta measure in stylometry,Footnote 4 it weighs the token frequencies in order to decrease the influence of less frequent (inflected) word tokens.

3.2 Cluster analysis

The main domain of basic stylometry methods is clustering different texts according to their authors. Authors with similar styles are clustered together. Since style is dependent upon linguistic features such as vocabulary use, word frequencies, and collocations, we expect authors from the same region to be clustered together meaning that their language is similar to each other, but differs systematically from the language of authors from other regions.

For our dataset labeled ‘old’, i.e. Western and Eastern texts written before WWII, apart from some confusion and the outlier Ivan Nečuj-Levyc’kyj (see below), the clustering is rather obvious, as can be seen in Figs. 1a and 1b.

Additionally to hierarchical clustering (Eder, 2017a), we visualize the data in a NeighborNet (Bryant & Moulton, 2004; von Waldenfels, 2014). NeighborNets are comparable to hierarchical clustering as they also divide the data into increasingly smaller groups based on the Nearest-Neighbor-Tree building algorithm. The main advantage of NeighborNets, however, is that they can visualize conflicting clustering, shown as rectangles or trapezoids in the graph. They therefore visualize more variation in this data and are less prone to display large differences in their structure based on small differences in the input data that could also be discarded as noise. The more robust NeighborNet in Fig. 1b confirms the clustering found by hierarchical clustering and also shows that Western and Eastern texts are well divided.

However, for our newer dataset with Western and Eastern texts written after WWII, the clustering isn’t that obvious. The linguistic features that the stylo algorithm took into account, i.e., the 500 most frequent words, are similar in some Western and Eastern texts, leading to them being clustered together, as can be observed from Figs. 2a, 2b.

This means that, based on our data, we see an overall tendency for differences between the two groups to be minor. Again, we also visualize the distances between texts in a NeighborNet, confirming our assessment with a visualization technique less sensitive to noise.

While the visualization of groups is an important technique that allows us to follow up on groups and individual outliers, a more principled approach is to numerically measure how well Eastern and Western texts fall into distinct groups. To do this, we use Nearest Shrunken Centroids (NSC), a supervised classification algorithm included in the stylo package that attempts to maximize the division into the groups we want to identify by performing cross-validated supervised classifications and pinpointing structural and lexical differences between these groups. The advantage of the cross-validation approach is a lower degree of loss of information. While the most common way of model training is to split the corpus into a training and validation set, cross-validation-trained models are trained and validated several times, based on every text within the corpus (Eder, 2017b).

Figure 3 shows the performance of the NSC classifier depending on how many most frequent words (MFWs) are taken into account. The graph clearly shows that, already taking into account the 200 most frequent words, the F1 scoreFootnote 5 of the division of Eastern and Western texts in the Old corpus, i.e., prewar texts, reaches short of 100 percent. Distinguishing the Eastern and Western texts written after the war, in contrast, is much harder and reaches just around 80 percent. We interpret this to mean that due to tendencies of convergence of the language used in the West and in the East, it is harder for the algorithm to classify newer texts correctly.

Figure 3 also shows how well prewar Western and prewar Eastern texts can be distinguished from postwar Western and Eastern texts, respectively. The line representing prewar and postwar texts from the West (‘West’ in the graph) reaches almost .95 taking into account the 400 most frequent words. This we take to mean that the language written in the West changed considerably between the two periods. Pre- and postwar texts written in the East, in contrast, are much more difficult to distinguish and the performance measured as F1 score only reaches around 80%.

These measures thus suggest that there is more diachronic continuity in the language of texts written in the East than in the West. In other words, we see evidence for a stronger influence of the Eastern than the Western norm in the formation of the new postwar standard.

An important next step to confirm this result would be to look at a larger number of texts than in this pilot study. Moreover, one could take a more qualitative view, investigate outliers and understand which place certain texts and authors take on the clines between East and West, pre- and postwar. However, we leave this for further research and turn to a different qualitative question: which features – i.e., words – are relevant in distinguishing different groups of texts?

3.3 NSC: zooming in from a bird’s-eye view

A further feature of the classify-function in the stylo package using NSC is that it is possible to output the most significant word tokens that are different in two subcorpora. Simply put, NSC allows zooming in from the bird’s-eye view characteristic for the bulk of stylometric methods to individual features such as words (and, via function words with a high frequency, morpho-syntactic characteristics). We can thus take a more qualitative view and find and evaluate these features. In this section, we examine the set of prewar Western and Eastern texts, asking why certain authors cluster differently than others and how the Western and Eastern texts differ systematically.

Using NSC, we first analyzed the features that distinguish the main outlier Ivan Nečuj-Levyc’kyj from other old Eastern texts. We found that the single most significant distinguishing feature is Nečuj-Levyc’kyj’s use of неначе ‘as if’. It gained by far the highest distinguishing score observed in all our experiments (above 5) and is, thus, strongly associated with Nečuj-Levyc’kyj’s style.

When compared to all other (Western and Eastern) old texts (Fig. 4), it becomes obvious that неначе is a feature specific to the individual style of the author and, judging from its frequency, one of his favorite words, which is one reason for him being the main outlier in the trees reported above.

Interestingly, even though Nečuj-Levyc’kyj sticks out and неначе was identified as the main reason for that, неначе isn’t among the 20 most significant features distinguishing all old Eastern texts (including Nečuj-Levyc’kyj’s) from all old Western texts. This means that, overall, other features are more significant when it comes to differences between old Western and old Eastern texts. The five most significant words that distinguish old Eastern and old Central texts are presented in Table 2.

Most importantly (and perhaps not very surprisingly), the prepositions від vs. од ‘from’ are features that distinguish old Western from old Eastern texts, with від being more popular in the West and од more popular in the East (cf. the positive, respectively negative values of the figures in rows 1 and 4).

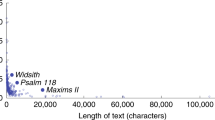

As can be seen in the left part of the two-dimensional plot represented in Fig. 5, there is a relatively clear-cut division between central texts that (almost) exclusively use од and western texts that (almost) exclusively use від. As a matter of fact, many of the texts without від and a high frequency of од are also from Nečuj-Levyc’kyj, who reportedly used this form exclusively (Simonyč, 1919: 55),Footnote 6 and others have been written by the second outlier in the trees Adrian Kaščenko. Dialectological data supports this relatively clear-cut division and the well-known assertion that, even though there were attempts to codify these forms as positional variants dependent on the preceding sound (Simonyč, 1919: 55), at the beginning of the 20th century, Ukrainian was pluricentric with one center in Galicia and another one in Central/East Ukraine (Matvijas, 2013).

For the postwar corpus, the clear-cut division between East and West has almost completely vanished, see the right part of Fig. 5. While there are some outliers (especially Janovs’kyj’s Myr (žyva voda), where від is used very rarely), most of the texts from the West and from the East are rather indistinguishable with respect to this variable. We observe a clear, but somewhat asymmetric convergence, meaning that texts from the East took up від to a greater extent, while certain texts from the West took up од, albeit to a lesser extent.

As opposed to other lexical items (see, e.g., Švedova, 2021),Footnote 7 here, the East moved more towards the West and not the other way round diachronically.

The second most significant distinguishing feature in the old subcorpus according to Table 2 is при ‘at’. При is significantly more frequent in old texts from the West than in old texts from the East (see Fig. 6) and seems to be rather polyfunctional.

Collocation analysis using AntConcFootnote 8 (Anthony, 2022) revealed that there are several non-spatial collocations such as при помочі ‘by help’ that exhibit a high frequency in the West. Moreover, the center seems to prefer other prepositions in certain cases even with spacial meaning. Figure 7 shows that біля seems to be preferred over при in certain contexts in (predominantly old) Eastern text. This holds for коло ‘round’ in a similar way (Figure not reported).

Diachronically, we observe – notwithstanding a few outliers – a general decrease in the frequency of при and, thus, the “de-westernization” of modern Standard Ukrainian in this respect, in line with the overall tendency described in Švedova (2021).

Regarding the third-ranked distinguishing feature in the comparison of old Western and Eastern texts, the conditional marker би, there is no immediate counterpart used in the East (according to the NSC algorithm, the short variant б is not a significant distinguishing feature). When comparing the frequencies of би in all four groups, it is obvious that it is used more often in the West (and considerably more often in old texts from the West), see Fig. 8.

When plotting би against its possible (albeit not significantly distinguishing) counterpart б for the old subcorpus (Fig. 9), it becomes obvious that би is clearly dispreferred in the East, while б isn’t dispreferred proportionally in the West. In other words, a simple interpretation that would posit that би is more often shortened to б in the East than in the West does not seem viable. Rather, the situation is more complex.

This issue clearly requires further investigation.

The fifth most significant distinguishing feature of the old subcorpus is перед ‘before’. We observe a clear-cut and highly significant division between old Western and old Eastern texts (Fig. 10), with перед being used significantly more frequently in the former. The NSC table did not reveal any obvious alternatives used instead of перед in those texts where перед is used infrequently, which prompted us to conduct a collocation analysis.

The collocation analysis (using AntConc) revealed that перед seems to be used in a temporal sense more often in old Western texts: хвилиною ‘a minute’, хвилею ‘a moment’, or роками ‘years’ are among the top ten most significant collocations, whereas these collocations do not occur in the East. Similar to the preposition при discussed above, our analysis suggests that the contexts where перед is used in the East are wider than in the West. While diachronic analysis did not reveal a clear-cut picture, it suggests that one can observe diachronic convergence – new Western texts still tend to have a higher mean frequency of перед than new Eastern texts, but variation is rather high and the respective boxplots overlap.

4 Conclusion

In our analysis, we applied stylometric methods to analyze variation and change in 20th century Ukrainian. Using raw data taken from the GRAC, we created four subcorpora overall to cover both pre- and post-WWII texts and texts from the Western and the Central Ukrainian region.

The bird’s-eye view clustering using stylo trees and splitstrees confirmed that old (pre-WWII) texts from the Western and Eastern varieties of Standard Ukrainian are clearly distinguishable, while newer (post-WWII) texts do not cluster as clearly, suggesting diachronic convergence. Furthermore, the diachronic difference between the Western pre- and postwar texts turned out to be more easily detectable than between the Eastern pre- and postwar texts. This is an argument in favor of a more noticeable shift and stronger break in the continuity of standards in the West than in the East.

Starting from this observation, we zoomed in using the most distinguishing features in the subcorpora computed by the NSC algorithm, identified and explained outliers (such as the preferred use of неначе by Ivan Nečuj-Levyc’kyj) and analyzed individual linguistic variables such as the opposition од vs. від, при, би (versus б), and перед. We applied n-gram and collocation analysis to shed light on the underlying factors responsible for the differences. Using appropriate visualization techniques, we confirmed the known diachronic convergence away from од towards від. Regarding the other variables, we uncovered some hitherto unknown structural differences, namely that prepositions such as при and перед seem to be used in a wider range of functions and contexts in old Western texts, with some of the functions apparently being lost in the later development. Би (versus б) requires additional research, би seems to be dispreferred in old Eastern texts, but its use within different n-grams might play a role as well.

In our analysis, we demonstrated that stylometry and, in particular, the NSC algorithm, is a viable method to start corpus analysis with an inductive approach, i.e., without a predefined hypothesis as to which specific variables to analyze. After uncovering structural differences between two subcorpora, it subsequently allows zooming in to analyze specific variables identified by the NSC tables both quantitatively and qualitatively.

Future research perspectives include refining this approach and the pipeline of using NSC to identify variables of interest for advanced statistical analysis of linguistic variation and change in Ukrainian and other languages.

Data Availability

We used data from the GRAC (uacorpus.org).

Notes

“Central” and “Eastern” are used largely synonymously in this paper, as we use text that originated in Kyiv and Central Ukraine as the most productive center where the Eastern Ukrainian Standard was written. This reflects the fact that in GRAC, texts from the Kyiv region are tagged as “central” texts. For this reason, “Central” appears as a designation in our input data and, consequently, in some figures produced using these data. In these figures, “Central” is thus to be understood as representing the Eastern variant.

GRAC is a corpus curated by a human investigator, as opposed to automatically acquired web corpora, which are easily larger, but hardly as comprehensive and representative.

As shown below (Fig. 3), classification performance stabilized at 500 MFW, which is why we used 500 MFW in our experiments.

“Delta, as defined by Burrows, is a distance measure. It describes the distance between one text and a group of texts. This group is taken as a representation of the style of a period, a text genre at some time.” (Evert et al., 2017).

For an explanation of different classification methods, see Eder (2021).

We encountered a dozen or so instances of від in his texts used for this study, as opposed to more than 2,000 instances of од.

Using GRAC, Švedova (2021) conducted a corpus analysis, comparing 117 synonymous rows of Eastern and Western Ukrainian content lexemes. She concluded that the new (post-1930s) Standard Ukrainian norm has an Eastern Ukrainian foundation.

AntConc (https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software/antconc/) is an application that can be used to conduct corpus-linguistic analysis of plain-text corpora. Using our GRAC data, we created a corpus in AntConc and used the built-in collocation analysis function, i.e., in this case, we searched for the most significant collocates of при.

References

Ahlmann-Eltze, C., & Patil, I. (2021). ggsignif: R package for displaying significance brackets for ‘ggplot2’. PsyArxiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/7awm6.

Anthony, L. (2022). AntConc (Version 4.0.10) [Computer software]. Tokyo: Waseda University. https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software.

Bryant, D., & Moulton, V. (2004). Neighbor-Net: an agglomerative method for the construction of phylogenetic networks. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 21(2), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msh018.

Burrows, J. (2002). ‘Delta’: a measure of stylistic difference and a guide to likely authorship. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 17(3), 267–287. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/17.3.267.

Eder, M. (2011). Style-markers in authorship attribution: a cross-language study of the authorial fingerprint. Studies in Polish Linguistics, 6, 99–114.

Eder, M., Rybicki, J., & Kestemont, M. (2016). Stylometry with R: a package for computational text analysis. R Journal, 8(1), 107–121. https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2016/RJ-2016-007/index.html.

Eder, M. (2015). Taking stylometry to the limits: Benchmark study on 5,281 texts from “Patrologia Latina”. In Digital humanities 2015: conference abstracts. Retrieved July 14, 2022, from https://dh-abstracts.library.cmu.edu/works/2364.

Eder, M. (2017a). Visualization in stylometry: cluster analysis using networks. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 32(1), 50–64. https://academic.oup.com/dsh/article/32/1/50/2957386?login=false.

Eder, M. (2017b). Cross-validation using the function classify (). Computational Stylistics Group. Retrieved July 13, 2022, from https://computationalstylistics.github.io/docs/cross_validation.

Eder, M. (2021, July 27). Performance measures in supervised classification. Computational Stylistics Group. Retrieved May 5, 2022, from https://computationalstylistics.github.io/blog/performance_measures/.

Evert, S., Proisl, T., Jannidis, F., Reger, I., Pielström, S., Schöch, C., & Vitt, T. (2017). Understanding and explaining Delta measures for authorship attribution. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 32(2), ii4–ii16. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqx023.

Górski, R. L., Król, M., & Eder, M. (2019). Zmiana w języku. Studia kwantytatywno-korpusowe. Kraków: IJP PAN.

Lotoc’ka, N. (2021). Statistical research of the colour component ЧОРНИЙ (BLACK) in R. Ivanychuk’s text corpus. In Main conference: Vol. I. CEUR workshop proceedings. Proceedings of the 5th international conference on computational linguistics and intelligent systems (pp. 486–497). COLINS 2021, Lviv, Ukraine, 22–23 April 2021. http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2870/paper36.pdf.

Matvijas, I. H. (2013). Vzajemodija sxidnoukraïns’koho j zaxidnoukraïns’koho variantiv literaturnoï movy v ustalenni norm u haluzi syntaksysu. Movoznavstvo, 1, 3–8.

Moser, M. (2016). New contributions to the history of the Ukrainian language. Toronto, Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press.

Mosteller, F., & Wallace, D. L. (2007 [1964]). Inference and disputed authorship: The Federalist (The David Hume Series). Stanford: Center for the Study of Language and Information.

R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

Rabus, A., & Švedova, M. (2021). Morphological variation in Ukrainian regional varieties: a corpus study. Slavia, XC(1), 1–24.

RStudio Team (2022). RStudio: integrated development for R. Boston: RStudio, PBC. http://www.rstudio.com/.

Shevelov, G. Y. (1966). Die ukrainische Schriftsprache 1798–-1965: ihre Entwicklung unter dem Einfluß der Dialekte. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Shevelov, G. Y. (1979). A historical phonology of the Ukrainian language. Heidelberg: Winter.

Simonyč, V. (1919). Hramatyka ukraïns’koï movy dlja samonavčannja ta v dopomohu škil’nij naucï. Kyïv-Ljajpcig: Kolomyja.

Stamatatos, E. (2009). A survey of modern authorship attribution methods. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60, 538–556. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21001.

Starko, V. (2021). Implementing semantic annotation in a Ukrainian corpus. In Main conference: Vol. I. CEUR workshop proceedings. Proceedings of the 5th international conference on computational linguistics and intelligent systems (pp. 435–447). COLINS 2021, Lviv, Ukraine, 22–23 April 2021. http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2870/paper32.pdf.

[Švedova] Shvedova, M. O., von Waldenfels, R., Yarygin, S., Rysin, A., Starko, V., Nikolajenko, T., et al. (2017–2022). GRAC: General Regionally Annotated Corpus of Ukrainian. Electronic resource: Kyiv, Lviv, Jena. Available at uacorpus.org.

Švedova, M. O. (2021). Leksyčna variantnist’ v ukraïns’kij presi 1920–1940-x rokiv i formuvannja novoï leksyčnoï normy (korpusne doslidžennja). Movoznavstvo, 1, 16–35.

[Švedova] Shvedova, M. O., von Waldenfels, R. (2021). Regional annotation within GRAC, a large reference corpus of Ukrainian: issues and challenges. In Main conference: Vol. I. CEUR workshop proceedings. Proceedings of the 5th international conference on computational linguistics and intelligent systems (pp. 32–45). COLINS 2021, Lviv, Ukraine, 22–23 April 2021. http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2870/paper4.pdf.

Taran, O. S., & Lebedenko, J. M. (2021). Semantyko-dystrybutyvnyj analiz slenhizmiv na osnovi danyx korpusu GRAK. Aktual’ni problemy filolohiï ta perekladoznavstva, 1(21), 119–123.

von Waldenfels, R. (2014). Explorations into variation across Slavic: taking a bottom-up approach. In B. Szmrecsanyi & B. Wälchli (Eds.), Aggregating dialectology, typology, and register analysis: linguistic variation in text and speech (Vol. 28, pp. 290–323). Berlin: de Gruyter.

von Waldenfels, R., & Eder, M. (2016). A stylometric approach to the study of differences between standard variants of Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian, or: is the Hobbit in Serbian more Hobbit or more Serbian? Russian Linguistics, 40, 11–31.

Wickham, H. (2016). ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Marija Švedova (Kyiv/Warsaw), Maciej Eder (Cracow), and Stefan Heck (Jena) for valuable help. The usual disclaimers apply.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Funding sources for this paper include the German Research Foundation (DFG, project “Rusyn as a minority language across state borders: a quantitative perspective”, RA 2212/2-2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Ruprecht von Waldenfels is one of the curators of GRAC. Apart from that, we declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below are the links to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lahjouji-Seppälä, M.Z., Rabus, A. & von Waldenfels, R. Ukrainian standard variants in the 20th century: stylometry to the rescue. Russ Linguist 46, 217–232 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-022-09262-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-022-09262-9