Abstract

Morphologically unmarked transitive (or accusative) impersonals, often also referred to as Adversity Impersonals or Elemental Constructions, have long been considered a primarily East Slavic phenomenon, with a somewhat marginal status in Polish. More recent research has claimed that these impersonal constructions also occur in other West Slavic languages and even in Slovenian. The present paper refines some of the previous assumptions about morphologically unmarked transitive impersonals in twelve Slavic and two non-Slavic languages by drawing on the results of a parallel corpus study. The analysis of empirical data suggests that it is necessary to identify the Štokavian dialectal continuum as a transitional area with a declining acceptability of morphologically unmarked transitive impersonals from the Northwest (Croatian) to the Southeast (Serbian). Moreover it will be shown that impersonals of this type are not an exclusively Slavic phenomenon.

Аннотация

Морфологически нейтральные безличные конструкции с переходными глаголами, часто также называемые ‘Adversity Impersonals’ или ‘стихийные конструкции’, традиционно считаются особенностью в основном восточнославянских языков и маргинальным явлением в польском языке. Недавние исследования показали, что такого рода безличные конструкции также встречаются в других западнославянских языках и даже в словенском. В настоящей статье, исходя из анализа данных параллельного корпуса и учитывая двенадцать славянских и два неславянских языка, пересматривается ряд предположений о морфологически нейтральных безличных конструкциях с переходными глаголами. Анализ эмпирических данных указывает на то, что штокавский диалектный континуум следует воспринимать как переходное пространство, в котором приемлемость безличных конструкций с переходными глаголами снижается с северо-запада (хорватский) на юго-восток (сербский). Кроме того, показывается, что такого рода безличные конструкции не являются исключительно славянским явлением.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Abbreviations for languages: Bg—Bulgarian; BCS—Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian, Bn—Bosnian, BRu— Belorussian, Cr—Croatian, Cz—Czech, Pl—Polish, Ru—Russian, Slk—Slovakian, Sln—Slovene, Sr—Serbian, Ukr—Ukrainian, Upper Sorb.—Upper Sorbian. Abbreviations for grammar: aor – aorist, conj – conjunction; the other abbreviations used adhere to the Leipzig Glossing Rules https://www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/pdf/Glossing-Rules.pdf.

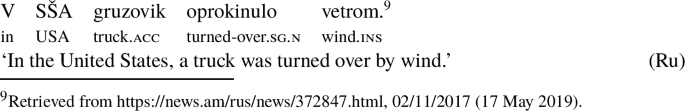

Impersonal constructions are defined here as constructions lacking an overt or contextually recoverable nominative subject, and whose verbal predicate is in the third person singular (and, if marked for gender, in the neuter gender). Transitive impersonals include a transitive verb and its direct object. The focus of this paper is restricted to morphologically unmarked transitive impersonals, that is, to transitive impersonals whose verbal predicate is in the active (unmarked) voice.Footnote 2 Morphologically unmarked transitive impersonals have also been referred to as Adversity Impersonals in English (since Babby 1994), or as stixijnye konstrukcii ‘Elemental Constructions’ in Russian (since Mustajoki and Kopotev 2005). To avoid any of the semantic implications associated with these two labels, the constructions in question will be called Active Transitive Impersonals here (henceforth ATI). Typical cases in point are:

- (1)

- (2)

The verbs occurring in ATI are usually regular transitive verbs in impersonal use (Kopejkin 1959, p. 227; Galkina-Fedoruk 1958, p. 146; Babajceva 2004, p. 216 for Russian ATI). Moreover, and although this is often acknowledged only implicitly, ATI are causative constructions (cf. Markman 2004; Lavine 2010; Junghanns et al. 2017; SchlundFootnote 3). More precisely, the core of ATI as a conceptual category consists of a causative construction expressing an event of external physical causation, that is, of prototypical physical causation in the sense of Croft (1991).Footnote 4 This adds a semantic note to the otherwise formal definition of ATI given above, but it does not reduce ATI to events with negative results (as implied by the label ‘Adversity Impersonal’), nor to events caused by natural forces (as implied by the label stixijnaja konstrukcija ‘Elemental Construction’).

ATI have often been regarded as a typical East Slavic, in particular Russian, phenomenon (e.g. Xodova 1958, p. 151). Yet, isolated examples of ATI from Slavic languages other than East Slavic can be found already in the earliest treatises on Slavic impersonals (Miklosich 1883, pp. 49–50; Jagić 1899, p. 20). Junghanns et al. (2017) provide a recent overview of the availability of morphologically marked and unmarked transitive impersonals in the Slavic standard languages.

The present paper seeks to examine these previous studies on ATI on an empirical basis, including not only a number of Slavic standard languages, but also the two non-Slavic languages German and Lithuanian. The Parallel Corpus of Slavic and other languages, henceforth ParaSolFootnote 5 is a suitable tool for this endeavor, cf. Sect. 3.Footnote 6

The goals of the present study are as follows. First, the study aims to determine in which Slavic (and non-Slavic) languages ATI can be attested empirically. Second, the study seeks to establish what syntactic patterns occur instead of ATI in languages that do not, or only marginally, tolerate them.

2 Active Transitive Impersonals (ATI) in Slavic

A major distinction among ATI in Slavic exists in the availability of an overt instrumental phrase indicating the semantic role of Cause.Footnote 7 Junghanns et al. (2017) assume that ATI with open Cause phrases are acceptable only in East Slavic, that is, in Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian, and in the West Slavic languages Polish and Slovakian (Junghanns et al. 2017, pp. 149f.). The following examples illustrate ATI with Cause phrases in the instrumental case in these languages:

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

- (7)

However, ATI with open Cause phrases seem to be so rare in Slovakian that Mrazek (1990, p. 104), while giving two examples from Slovakian, categorises them as exceptions.

Table 1 summarizes the availability of ATI with open Cause phrases in Slavic as assumed by Junghanns et al. (2017):

As distinguished from ATI with open Cause phrases, ATI without open Cause phrases are clearly more widespread in Slavic. Junghanns et al. (2017) assume that the following distribution of ATI without Cause phrases exists in Slavic (Table 2):

Tables 1 and 2 suggest that ATI without open Cause phrases exist, in principle, in all Slavic standard languages except Bulgarian and Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian, while ATI with open Cause phrases are only present in East Slavic and, to a lesser extent, in Polish and Slovakian. The corpus analysis conducted in Sect. 3 aims to check these assumptions on an empirical basis.

3 Corpus study

The study was conducted using the parallel corpus ParaSol (cf. fn. 6). The latest information available on the website dating from March 2014 indicates that the corpus includes 27 million tokens from 31 languages.Footnote 8 The tokens originate from post-war belletristic sources, namely novels that were originally written in one of the languages of the corpus. The corpus includes originals and translations in twelve Slavic languages: Belarusian, Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, Czech, Upper Sorbian, Slovakian, Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian, Bulgarian, and Macedonian. Moreover, ParaSol includes a number of texts in Germanic, Romance, Baltic and Finno-Ugric languages.

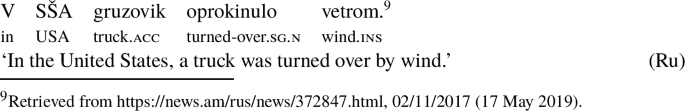

Since ATI are particularly well-established in Russian (Galkina-Fedoruk 1958, pp. 148f.; Ivić 1965), Russian was selected as the primary language in the queries, and all Slavic languages represented in ParaSol were chosen as aligned languages. All texts of the corpus that were available in Russian were included in the queries in order to find a relevant number of ATI, regardless of whether the texts were originally published in Russian or in another language represented in ParaSol. The queries included word forms of verbs that typically occur in ATI. These are causative verbs denoting instances of external physical causation that need not necessarily be initiated by an animate or even human instigator, such as sorvat’ ‘to rip off’, ubit’ ‘to kill’, udarit’ ‘to hit’, and the like. The verbs searched were derived from a database of Russian ATI compiled by Mustajoki and Kopotev (2005) for a study on Russian ATI and amended by Schlund (see fn. 4) for the same purpose. The search was restricted to the past tenseFootnote 9 because only the past is non-ambiguous with respect to the impersonal form.Footnote 10 This means that the queries were conducted for the exact forms of sorvalosg.n ‘ripped-off’, ubilosg.n ‘killed’, udarilosg.n ‘hit’, etc. Restriction to the past tense does not appear too problematic for the purpose of this study, since the past tense is the predominant tense in narrative texts, which constitute the ParaSol corpus. In this way, 106 Russian ATI could be retrieved from ParaSol, with the number of equivalents in other languages varying from 84 equivalents (in Polish) to 7 (in Upper Sorbian).

In a second step, the Russian ATI were divided into ATI with and without open Cause phrases. Then, descriptive categories to characterize the different kinds of equivalents attested for the Russian ATI in the other languages were developed.

Table 3 summarizes and illustrates the different types of equivalents of Russian ATI distinguished in the analysis. The first column indicates the coding number given to the categories in the coding procedure. The second column includes the name of the category. The middle column provides a representative Russian ATI, and the rightmost column gives an example from one of the aligned languages.

A distinction regarding whether the Cause or the Patient of a Russian ATI occurs as the nominative subject of an active construction in another language (categories 4 and 5) applies only to ATI with Cause phrases. Personal counterparts of Russian ATI without Cause phrases were simply classified as active. As the focus of the study is on structure, not on the lexicon, category 9 (free translation) was chosen only when the structure of the equivalent did not fit into any of the other descriptive categories, and not in cases in which only lexical differences occurred.

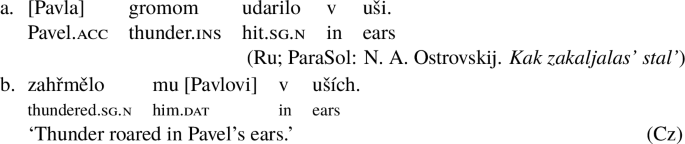

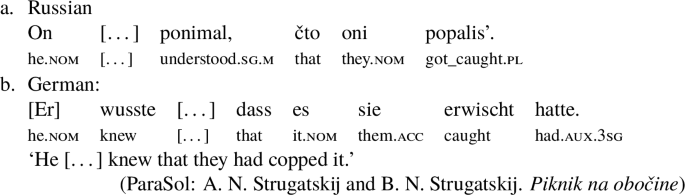

The categories are not above criticism. For instance, there is a tendency for quite heterogeneous constructions to be lumped together in categories 2 and 4. Since category 2 does not distinguish the type of impersonal construction used as an equivalent of a Russian ATI in another language, any kind of impersonal construction that is not an ATI will be included in this category. Examples (8) and (9) indicate cases in point:

- (8)

- (9)

Both Czech equivalents of the two Russian ATI in (8) and (9) are impersonal constructions, which is why they have been classified as category 2 equivalents. This, however, ignores the structural difference that (8b) is a reflexive impersonal, while (9b) is not.

Equivalents of Russian ATI labelled ‘active’ (category 4) may likewise include quite different things in one category. The following examples illustrate this heterogeneity:

- (10)

- (11)

- a.

[…] tut

ego

s

xrustom

udarilo

v

zatylok.

him.acc

with

chrunch

hit.sg.n

in

neck

(Ru; ParaSol: Arkadij i Boris Strugackie. Gadkie lebedi)

- b.

[…] v tozi mig

glavata

mu

izpraščja

ot

udar

v

tila.

head_art

him.dat

cracked.3sg.aor

from

hit

on

neck

‘[…] at that moment he was violently hit on the neck.’ (Bg)

- a.

The Slovakian (10b) equivalent of the Russian ATI is structurally different from the Bulgarian one (11b); yet both are classified as belonging to category 4, that is, as active equivalents.

However, the small amount of data in this pilot study made it reasonable to not create too many categories and leave further differentiations to future studies.

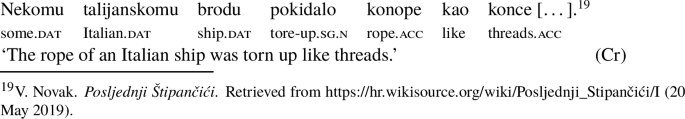

3.1 Equivalents of Russian ATI with Cause phrases

Table 4 gives the absolute numbers of the equivalents of Russian ATI with open Cause phrases in eleven other Slavic languages. The different shades of colors indicate the frequency of the respective equivalent type, with dark green indicating the most frequent equivalent found in a given language and light grey indicating the least frequent type.

Across all Slavic languages included in the study, personal transitive constructions with the Cause functioning as the subject are by far the most frequent structure (\(n = 154\)) used instead of Russian ATI with Cause phrases. This is true for all languages except East Slavic (Ukrainian and Belarusian). Equivalents in which the Patient of the Russian ATI figures as the subject of the active personal construction take second place, with a total number of \(n = 29\). Equivalents of Russian ATI in the passive voice are clearly less frequent, with a total number of only \(n = 11\). Even if one adds the recipient passive category, which is represented only in Polish and Czech with three cases altogether, the equivalents of Russian ATI in the active voice (\(n = 154\)) still outnumber all passive voice equivalents (\(n = 14\); 11 instances of participial passive and 3 instances of recipient passive) across all languages.

It is not surprising that ATI with Cause phrases occur most often in the two other East Slavic languages, Belarusian and Ukrainian. The only ATI with open Cause phrases attested outside of East Slavic are for Polish (\(n = 1\)) and Upper Sorbian (\(n = 2\)). Interestingly, the only Polish ATI with a Cause phrase occurs in an originally Polish text, more precisely in an instance of direct speech. It is thus authentically Polish and colloquially marked, something that is usually believed to be the case for Polish ATI (cf. Siewierska 1988, p. 276):

- (12)

Moreover, the semantic Cause denoted by the instrumental case is merely a Means rather than a Cause or even a Force, just like in the other Polish example (6) above. One possible explanation is that only Causes ranging low on the agentivity scale (like a Means or an Instrument) are acceptable in the Cause phrase of ATI in Polish, whereas natural forces, which typically fulfil the semantic role of Force in ATI, are acceptable as Causes of ATI in East Slavic.

The two alleged ATI with Cause phrases from Upper Sorbian occur within a single sentence:

- (13)

Před Pawłowymaj wóčkomaj zabłyskny płomjo, zelene kaž magnezij,

One might object that these examples are actually ambiguous between ATI and a regular, personal transitive construction. This is because it is hard to determine whether the subject of the first clause of the sentence, płomjo ‘flame’, functions as the subject of the two following clauses as well. More data that will probably have to be collected by additional methods of data eliciting is necessary to obtain a more detailed picture of the acceptability of ATI with open Cause phrases in Upper Sorbian.

The fact that ATI with Cause phrases could be attested in Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian and Polish is in line with the assumptions made by Junghanns et al. (2017, p. 151). The marginal acceptability of ATI with Cause phrases in Slovakian remains questionable as the corpus research yielded no such results. The two examples occurring within the same sentence in Upper Sorbian remain in doubt as well.

Figure 1 illustrates the shares of the respective categories for different language groups, namely East Slavic, West Slavic, and South Slavic. Exact percentages are given for the two most frequent equivalents in East Slavic, namely ATI and personal active constructions.

The percentages provide an almost equal picture for West and South Slavic, with the main difference being that ATI with Cause phrases and recipient passives are attested as equivalents of Russian ATI in West Slavic, but not in South Slavic.

3.2 Equivalents of Russian ATI without Cause phrase

Table 5 gives the absolute numbers of the different equivalent types attested for Russian ATI without Cause phrases.

As expected, Russian ATI without Cause phrases are more frequently rendered as ATI in the aligned languages (\(n=42\)) than Russian ATI with Cause phrases. However, cases in which the equivalent of a Russian ATI without a Cause phrase is likewise an ATI without a Cause phrase are again clearly outnumbered by cases in which a Russian ATI corresponds to the personal transitive construction across all languages (\(n = 92\)). Recipient passives are again attested only for West Slavic, this time for Polish only (\(n = 6\)).

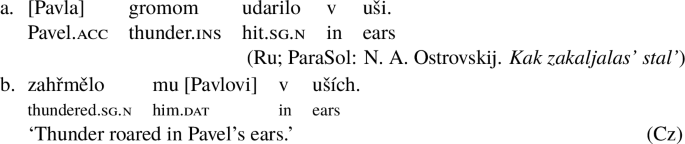

It seems counterintuitive that Russian ATI may be rendered as indefinite-personal constructions (Rus. neopredelenno-ličnye konstrukcii). This was the case in two Bulgarian examples from the same text. The following example is a case in point:

- (14)

Although indefinite-personal constructions refer to an unspecific, human Agent and ATI imply an unspecific inanimate, and hence necessarily non-human, Cause, both constructions can obviously function as equivalents. The two examples attested in the corpus are also in line with Cimmerling’s (2018, p. 19) observation that Russian ATI are often translated as indefinite-personal constructions in Bulgarian.

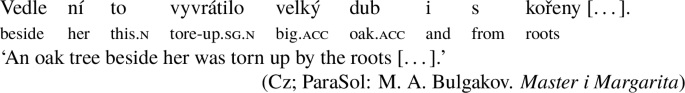

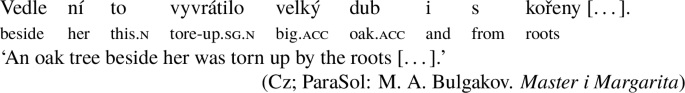

With respect to the ATI attested in Czech (\(n = 3\)), it is important to point out that all three instances include the indefinite pronoun to, which is in line with the observation made by Junghanns et al. (2017, pp. 151–153). Example (15) is a case in point:

- (15)

Therefore, it might have been equally justified to classify all instances of these types of alleged ATI in Czech as belonging to category 3 (that is, as active constructions with a neuter indefinite pronoun in the nominative subject). I have decided to include these cases into the ATI category proper nevertheless, as Czech to in cases like (15) is clearly less referential than Czech něco or Polish coś ‘something’ (the occurrence of which yielded the inclusion in category 3). In this respect, Czech toFootnote 11 seems to be an equivalent of the German expletive pronoun es rather than of German etwas ‘something’, the former of which is constitutive of ATI in German (see Sect. 4).

Interestingly, the one Slovakian example attested in Table 4 does not include an overt expletive pronoun (16). However, I have been able to find a Slovakian ATI with to (17):

- (16)

- (17)

Although Junghanns et al. (2017) note that ATI without Cause phrases occur in Slovenian as well, it is somewhat unexpected that Slovenian outnumbers not only the other South Slavic languages in the corpus data, but also Czech and Slovakian. The following two examples are given for illustrative purposes:

- (18)

- (19)

The one Croatian ATI reads as follows:

- (20)

One might think that a single example is not very meaningful. However, Croatian ATI do not seem to be as exceptional as previously believed. The following examples are cases in point:

- (21)

- (22)

- (23)

It is noteworthy that all examples carry a colloquial flavor. This is underlined by the fact that examples (21) through (23) all omit the perfect tense auxiliary, the present tense form of biti ‘to be’, which is also typical of colloquial use. The examples suggest that ATI without Cause phrases are not alien to colloquial Croatian. They also seem to occur typically in contexts of auxiliary loss, which is indicative of a transitional stage of the perfect evolving into an overall past tense (Meermann and Sonnenhauser 2016).

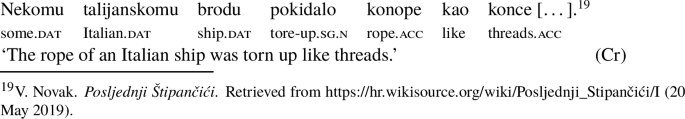

I also found one Štokavian example that is obviously not of Croatian origin:

- (24)

The fact that a subordinate clause is used instead of the infinitive (nisam mogla da gledam lit. ‘I could not that I see’ instead of nisam mogla gledatiinf, lit. ‘I could not see’) is indicative of a non-Croatian variant of Neoštokavian. Indeed, example (24) is a forum entry on a Bosnian information website about pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting. It is noteworthy that I have not been able to find any examples of ATI that could be ascribed to Serbian, which suggests that Neoštokavian represents a transitional area with decreasing acceptability of ATI without Cause phrases from Northwest (Croatian) to Southeast (Serbian).

Figure 2 provides an overview of the different categories of equivalents of Russian ATI without Cause phrases retrieved from the ParaSol corpus for the three groups of Slavic languages:

Importantly, six out of seven ATI attested in South Slavic are from Slovenian. Therefore, the percentages have been counted anew with Slovenian included in West Slavic. The share of ATI in South Slavic then drops from 8% to 1%, cf. Fig. 3.

4 ATI in non-Slavic languages

4.1 German

It has often been assumed that ATI, in particular when realized with open Cause phrases in the instrumental case, are an exotic property of (East) Slavic (Sulejmanova 1999, p. 172; Kizach 2014, p. 206). Yet, Miklosich (1883, p. 27) already indicated a number of German ATI occurring in the poem Der Taucher ‘The Diver’ by Friedrich Schiller:

- (25)

- (26)

More recently, Szucsich pointed out that Bavarian has ATI as well:

- (27)

- (28)

ATI in Bavarian dialects have even creeped into the local standard, as instances of ATI can be found in written documents of Bavarian origin on the Internet:

- (29)

- (30)

Importantly, the expression of physical, external Causes is not usually acceptable even in these colloquially flavored examples:

- (31)

Causes seem to be restricted to physiological, internal processes such as laughter or anger. These types of ATI are also acceptable in standard colloquial German and not restricted to dialects. Example (27) above, for instance, reads as follows in standard colloquial German:

- (32)

ATI in colloquial German are typically idiomatic in nature and have a figurative meaning:

- (33)

- (34)

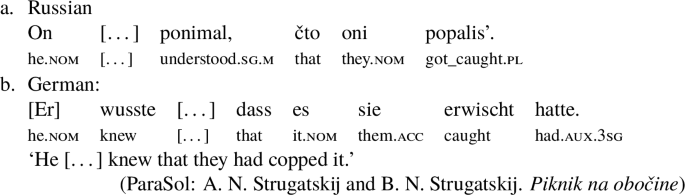

Curiously enough, I happened to come across examples in which German uses ATI without a Cause phrase while Russian features a personal construction. The following example is an illustrative case in point:

- (35)

4.2 Lithuanian

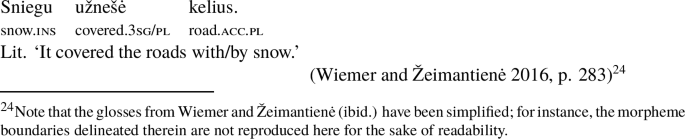

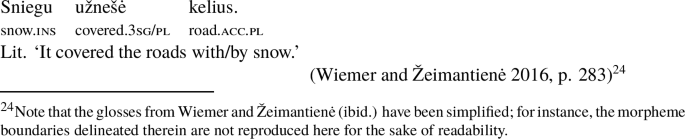

ATI also exist in Lithuanian. ATI in Lithuanian sometimes even allow for the open expression of a Cause by means of an instrumental phrase, just like East and some West Slavic languages. Wiemer and Žeimantienė (2016) give a number of examples of ATI with open Cause phrases in the instrumental:

- (36)

- (37)

- (38)

The authors note that this construction includes a causative verb and allows for realization with or without an instrumental phrase denoting the Cause of the event (Wiemer and Žeimantienė 2016, pp. 201, 270). Yet, a possible problem with ATI in Lithuanian is that the predicate is ambiguous between the third person singular and plural. However, cases like the above strongly suggest an interpretation of the predicate as 3rd person singular because there is no reason to assume the presence of human agents. Like their Slavic cognates, Lithuanian ATI with open Cause phrases lend themselves to reformulation by means of a regular, personal transitive construction (Wiemer and Žeimantienė 2016, p. 271).Footnote 12

The following citation from Lavine (2016, p. 111) about transitive impersonals in Lithuanian applies to East Slavic ATI as well: “Some Lithuanian externally caused verbs realize their non-Theme argument either as a nominative Agent (with a sentient, volitional Causer reading) or as an oblique Causer (giving “out-of-control” semantics) […].”

Example (39) is another instance of a Lithuanian ATI without an open Cause phrase:

- (39)

Interestingly, natural forces do not seem to be acceptable Causes in the instrumental phrases of Lithuanian ATI (Wiemer and Žeimantienė 2016, p. 300), which distinguishes Lithuanian ATI from ATI in East Slavic:

- (40)

As noted with respect to Polish in Sect. 3.1, the restriction on natural forces in Lithuanian ATI may be due to the fact that the semantic role of Force ranges higher on the animacy scale than other inanimate Causes, such as substances (sand, snow) and other entities associated with the semantic role of Means (e.g. the pimples in (37)). While the more agentive semantic role of Force seems to block encoding as a Cause in ATI in Lithuanian, Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian allow for the expression of a semantic Force in terms of an oblique in ATI.

5 Conclusion and further reasoning

Although the overall tendencies established here are in line with previous knowledge about the distribution of ATI in Slavic, the results also reveal some significant additional information. The corpus analysis suggests that the transitive, personal active construction constitutes the most frequent equivalent of Russian ATI with Cause phrases in West and South Slavic, while ATI are only strongly represented in the two other East Slavic languages, Ukrainian and Belarusian, in particular as equivalents of Russian ATI without Cause phrases.

The data presented in Sect. 3 call for a modification of the assumption that ATI “seem to be unattested only in BCS and Bg” (Junghanns et al. 2017, p. 148). While the tolerance of ATI indeed seems to decrease from Northern East Slavic (Russian) to Eastern South Slavic (Bulgarian), the Neoštokavian dialectal continuum appears to represent a transitional zone, with acceptability of ATI without Cause phrases decreasing from West (Croatian) to East (Serbian). As is the case with many other structural and lexical properties of the Neoštokavian dialectal continuum, Bosnian seems to constitute the connective link between Croatian in the West and Serbian in the East also with respect to ATI. What is more, ATI are not an exclusively Slavic phenomenon, as the German and Lithuanian data have shown.

As noted above, some of the categories to describe the equivalents of Russian ATI are heterogeneous and might profit from the introduction of more sophisticated subcategories, for instance by distinguishing different kinds of impersonal constructions used instead of Russian ATI, and possibly also by distinguishing different kinds of recipient passives used in West Slavic. Moreover, the method of comparing translations is not without risks, since translations may be biased or even incorrect (cf. Berger 2016, p. 39f. about potential downsides of translation comparison). This is why the data presented here are only a first step toward an empirically based typology of ATI in Slavic and non-Slavic languages. In the future, it will be necessary to gather more quantitative and qualitative empirical evidence, not only from corpus data, but also from acceptability tests and other ways of eliciting empirical data. Higher case numbers are of course required to review and refine the tendencies observed in this initial study, and research into dialectal variation will be particularly relevant in the domain of ATI.

Questions for future studies include, among others, questions relating to the mechanisms governing the use of an open expletive or semi-expletive pronoun in some Slavic languages (mainly Czech and Slovakian), an explanatory account of the Causes acceptable in open Cause phrases in different languages, and the nature of causation expressed by ATI in different languages. Moreover, a distinction between ATI and transitive ‘impersonalia tantum’, that is, morphologically unmarked transitive impersonals with truly impersonal verbs, which seem to also exist in Bulgarian (Junghanns et al. 2017, p. 161), will be necessary.

Notes

Morphologically unmarked transitive impersonals thus do not imply any change in valency and / or verbal morphology, which distinguishes them from morphologically marked transitive impersonals, such as the Polish and Ukrainian -no / -to-construction, or reflexive impersonals whose only argument is a direct object (cf. also Wiemer 1995; Wiemer and Žeimantienė 2016; Junghanns, Lenertová, and Fehrmann 2017 for this distinction). Examples in point are:

- (i)

Przesyłkę

dostarczono

dzisiaj

rano.

parcel.acc

delivered-no/-to

today

morning

‘The parcel has been delivered this morning.’ (Pl; Słoń 2007, p. 258)

- (ii)

Buduje

się

tutaj

szkołę.

build.3sg.pres

refl

here

school.acc

‘One builds a school here.’ (Pl; Krzek 2013, p. 186)

- (iii)

Vazu

bulo

rozbito

vitrom.

vase.acc

was.sg.n

broken.sg.n

wind.ins

‘The vase was broken by the wind.’ (Ukr; Lavine 2010, p. 105)

- (i)

Schlund, K., The Russian ‘Elemental Construction’ from a synchronic and diachronic perspective: an empirical contribution to the understanding of an impersonal construction in Slavic (unpublished postdoctoral thesis, University of Heidelberg, 2018).

The only deviance from prototypical physical causation exists in the absence of a prototypical Agent, that is, of an animate Causer who is in full control of the whole causative event. For a detailed analysis of Russian ATI as causative constructions, cf. Schlund’s postdoctoral thesis (see fn. 4 above).

This study is an extended and revised version of the pre-study presented in Schlund (2017).

Semantic role labels are capitalized. Junghanns et al. (2017) ascribe the semantic role of Force to the instrumental phrase in ATI. I prefer the semantic role label of Cause as a cover term for different types of inanimate causers because the notion of Force is less suitable to capture the semantic role of substances in ATI like the following ones, which figure prominently among the Cause phrases of ATI:

- (i)

Snegom

pokrylo

čast’

Serbii.

snow.ins

covered.sg.n

part.acc

Serbia.gen

‘Part of Serbia covered with snow.’ (Ru)

(Retrieved from https://112.ua/video/snegom-pokrylo-chast-serbii-197411.html,

05/16/2016 (30 January 2018)

- (ii)

[D]rogi

zaniosło

wydmami […].

roads.acc

covered.sg.n

dunes.ins

‘The roads were covered with dunes.’ (Pl; ParaSol: S. Lem. Głos Pana)

- (i)

http://www.parasolcorpus.org/, last access 30 July 2019.

Note, however, that ATI are not restricted to the past tense.

Of course, potential hits had to be checked for the presence of a neuter noun or pronoun functioning as the syntactic nominative subject to make sure that only ATI were included in the data.

Czech to is a highly polysemic lexeme whose functions include, among others, use as a particle and different kinds of pronouns (cf. Berger 1993). Although definitely worth further study, the use of to in ATI and other impersonal constructions goes beyond the scope of this paper.

The fact that the personal cognates of ATI are always grammatically correct sentences does not, of course, imply that they are functionally identical with ATI. The functional (pragmatic, discursive, stylistic) aspects of ATI and their corresponding personal transitive clauses are not in the focus of this paper.

References

Babajceva, V. V. (2004). Sistema odnosostavnyx predloženij v sovremennom russkom jazyke. Moskva.

Babby, L. (1994). A theta-theoretic analysis of adversity impersonal sentences in Russian. In S. Avrutin, S. Franks, & L. Progovac (Eds.), Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL-2). The MIT meeting 1993 (Michigan Slavic Materials, 36, pp. 25–67). Ann Arbor.

Berger, T. (1993). Das System der tschechischen Demonstrativpronomina. Textgrammatische und stilspezifische Gebrauchsbedingungen (Habilitationsschrift. Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München). Retrieved from https://homepages.uni-tuebingen.de/tilman.berger/HabilBerger.pdf (30 July 2019).

Berger, T. (2016). Noch einmal Imperfektiva in Handlungsfolgen. Wiener Slawistischer Almanach, 77, 37–54.

Cimmerling, A. V. (2018). Impersonal’nye konstrukcii i dativno-predikativnye struktury v russkom jazyke. Voprosy jazykoznanija, 5, 7–33.

Croft, W. (1991). Syntactic categories and grammatical relations. The cognitive organization of information. Chicago, London.

Faßke, H. (1981). Gramatika hornjoserbskeje spisowneje rěče přitomnosće. Morfologija. Grammatik der obersorbischen Schriftsprache der Gegenwart. Morphologie (Unter Mitarbeit von Siegfried Michalk). Bautzen.

Galkina-Fedoruk, E. M. (1958). Bezličnye predloženija v sovremennom russkom jazyke. Moskva.

Ivić, M. (1965). On the origin of the Russian sentence type (ego) zavalilo snegom. Die Welt der Slaven, X (3–4), 317–321.

Jagić, V. (1899). Beiträge zur slavischen Syntax. Wien.

Junghanns, U., Lenertová, D., & Fehrmann, D. (2017). Parametric variation of Slavic accusative impersonals. In O. Müller-Reichau & M. Guhl (Eds.), Aspects of Slavic linguistics. Formal grammar, lexicon and communication (Language, Context, and Cognition, 16, pp. 140–165). Berlin, Boston.

Kizach, J. (2014). A multifactorial analysis of the Russian adversity impersonal construction. Russian Linguistics, 38, 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-014-9128-z.

Kopejkin, M. A. (1959). Sinonimika bezličnyx i ličnyx predloženij v sovremennom russkom jazyke. Učenye zapiski Kujbyševskogo gosudarstvennogo pedagogičeskogo instituta imeni V. V. Kujbyševa, 26, 213–233.

Krzek, M. (2013). Interpretation and voice in Polish SIĘ and -NO/-TO constructions. In I. Kor Chahine (Ed.), Current studies in Slavic linguistics (Studies in Language Companion Series, 146, pp. 185–197). Amsterdam.

Lavine, J. E. (2010). Case and events in transitive impersonals. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 18(1), 101–130. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsl.0.0035.

Lavine, J. E. (2016). Variable argument realization in Lithuanian impersonals. In A. Holvoet & N. Nau (Eds.), Argument realization in Baltic (Valency, Argument Realization and Grammatical Relations in Baltic, 3, pp. 107–135). Amsterdam, Philadelphia.

Markman, V. G. (2004). Causatives without causers and Burzio’s generalization. In K. Moulton & M. Wolf (Eds.), Proceedings of the thirty-fourth annual meeting of the North East Linguistic Society (NELS, 34, Vol. 2, pp. 425–439). Amherst.

Meermann, A., & Sonnenhauser, B. (2016). Das Perfekt im Serbischen zwischen slavischer und balkanslavischer Entwicklung. In A. Bazhutkina & B. Sonnenhauser (Eds.), Linguistische Beiträge zur Slavistik. XXII. JungslavistInnen-Treffen in München. 12.–14., September 2013 (Specimina Philologiae Slavicae, 187, pp. 83–110). Leipzig.

Meyer, R., & von Waldenfels, R. (2006). ParaSol: a Parallel Corpus of Slavic and other languages. Available at http://parasolcorpus.org/.

Miklosich, F. (1883). Subjectlose Sätze. Wien.

Mrazek, R. (1990). Sravnitel’nyj sintaksis slavjanskix literaturnyx jazykov. 1: Isxodnye struktury prostogo predloženija (Opera Universitatis Purkynianae Brunensis Facultas Philosophica. Spisi Univerzity J. E. Purkyně v Brně Filozofická Fakulta, 289). Brno.

Mustajoki, A., & Kopotev, M. V. (2005). Lodku uneslo vetrom: uslovija i konteksty upotreblenija russkoj ‘stixijnoj’ konstrukcii. Russian Linguistics, 29(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-004-5205-z.

Schlund, K. (2017). Russkaja ‘stixijnaja konstrukcija’ (model’ “ee ubilo molniej”) i ee ėkvivalenty v drugix slavjanskix i neslavjanskix jazykax. Pilotovyj korpusnyj analiz. In E. Gutiérrez Rubio, E. Kislova, & D. Kruk (Eds.), Contributions to the 20th annual scientific conference of the Association of Slavists (Polyslav). Moscow, September 6th–8th, 2016 (Die Welt der Slaven. Sammelbände. Sborniki, 62, pp. 160–169). Wiesbaden.

Siewierska, A. (1988). The passive in Slavic. In M. Shibatani (Ed.), Passive and voice (Typological Studies in Language, 16, pp. 243–289). Amsterdam, Philadelphia.

Słoń, A. (2007). The ‘impersonal’ impersonal construction in Polish. A Cognitive Grammar analysis. In D. Divjak & A. Kochańska (Eds.), Cognitive paths into the Slavic domain (Cognitive Linguistics Research, 38, pp. 257–287). Berlin.

Sulejmanova, O. A. (1999). Problemy russkogo sintaksisa: semantika bezličnyx predloženij. Moskva.

Szucsich, L. (2008). Evidenz für syntaktische Nullen aus dem Burgenlandkroatischen, Polnischen, Russischen und Slovenischen: Merkmalsausstattung, Merkmalshierarchien und morphologische Defaults. Zeitschrift für Slawistik, 53(2), 160–177.

Von Waldenfels, R. (2011). Recent developments in ParaSol: Breadth for depth and XSLT based web concordancing with CWB. In D. Majchráková & R. Garabík (Eds.), Natural language processing, multilinguality. Sixth international conference Modra, Slovakia, 20–21 October 2011. Proceedings (pp. 156–162). Bratislava. Retrieved from https://korpus.sk/~slovko/2011/ (31 January 2020).

Wiemer, B. (1995). Zur Funktion von Sätzen ohne grammatisches Subjekt im Polnischen und Russischen. Auszüge aus einer vergleichenden Corpusanalyse zu einer ausgewählten Textsorte. Wiener Slawistischer Almanach, 35, 311–329.

Wiemer, B., & Žeimantienė, V. (2016). Contexts for the choice of genitive vs. instrumental in contemporary Lithuanian. In A. Holvoet & N. Nau (Eds.), Argument realization in Baltic (Valency, Argument Realization and Grammatical Relations in Baltic, 3, pp. 259–331). Amsterdam, Philadelphia.

Xodova, K. I. (1958). Tvoritel’nyj padež v stradatel’nyx konstrukcijax i bezličnyx predloženijax. In S. B. Bernštejn (Ed.), Tvoritel’nyj padež v slavjanskix jazykax (pp. 127–158). Moskva.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schlund, K. Active transitive impersonals in Slavic and beyond: a parallel corpus analysis. Russ Linguist 44, 39–58 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-020-09221-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-020-09221-2