Abstract

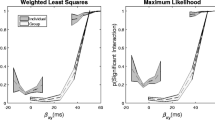

We develop and test a model which links information acquisition decisions to the hedonic utility of information. Acquiring and attending to information increases the psychological impact of information (an impact effect), increases the speed of adjustment for a utility reference-point (a reference-point updating effect), and affects the degree of risk aversion towards randomness in news (a risk aversion effect). Given plausible parameter values, the model predicts asymmetric preferences for the timing of resolution of uncertainty: Individuals should monitor and attend to information more actively given preliminary good news but “put their heads in the sand” by avoiding additional information given adverse prior news. We test for such an “ostrich effect” in a finance context, examining the account monitoring behavior of Scandinavian and American investors in two datasets. In both datasets, investors monitor their portfolios more frequently in rising markets than when markets are flat or falling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The idea that ostriches hide their head in the sand is a myth. According to the Canadian Museum of Nature (http://www.nature.ca/notebooks/english/ostrich.htm): “If threatened while sitting on the nest, which is simply a cavity scooped in the earth, the hen presses her long neck flat along the ground, blending with the background. Ostriches, contrary to popular belief, do not bury their heads in the sand.”

In Akerlof and Dickens (1982), workers in dangerous work environments downplay the severity of unavoidable risks. In Köszegi (1999), Bodner and Prelec (2001), and Benabou and Tirole (2006), people take actions to persuade themselves, as well as others, that they have desirable personal characteristics that they may not have. In Benabou and Tirole (2002), people exaggerate their likelihood of succeeding at a task to counteract inertia-inducing effects of hyperbolic time discounting. In Brunnermeier and Parker (2002) and Loewenstein (1985, chapter 3), agents maximize total well-being by balancing the benefits of holding optimistic beliefs and the costs of basing actions on distorted expectations. In Rabin and Shrag (1999), people interpret evidence in a biased fashion that responds more strongly to information consistent with what they are motivated to believe.

Our intuition a priori is that investors are more likely to monitor their portfolios when the market is neutral than when it is sharply down. As will be evident in the following section, the data provide mixed support for this prediction. The prior analysis may seem to be at odds with this intuition since the model says that people will never monitor their portfolios when the market is flat but that, for some parameter values, investors will monitor when the market news is negative. However, the magnitude of the disincentive for attention can be greater when the market is down than when it is flat if α is large and θ is close to 0.

If r 2 is an independently distributed, mean-zero shock that is realized and automatically learned at date 2, then the attention differential is \(\Delta J\left( p \right) = \left( {1 + \alpha } \right){\text{E}}\left[ {u\left( {p + r_{\text{d}} } \right)} \right] + {\text{E}}\left[ {u\left( {r_2 } \right)} \right] - \left[ {u\left( p \right) + {\text{E}}\left[ {u\left( {\theta p + r_{\text{d}} + r_2 } \right)} \right]} \right]\). In this case, \({\text{E}}\left[ {u\left( {p + r_{\text{d}} } \right)} \right] <u\left( p \right)\) and \({\text{E}}{\left[ {u{\left( {r_{2} } \right)}} \right]} > {\text{E}}{\left[ {u{\left( {r_{{\text{d}}} + r_{2} } \right)}} \right]}\) where the later inequality follows because r 2 second-order stochastic dominates r d + r 2.

Although LOOKUPS t is defined as the number of logins less the number of portfolio rebalancing transactions, there may be look-ups motivated by a potential interest in trading which did not ultimately result in trades.

If ex ante utility forecasts are erroneous (see Loewenstein, O’Donoghue and Rabin 2003), then the ostrich effect could cause investors to pay attention too little or too much.

References

Akerlof, G., & Dickens, W. (1982). The economic consequences of cognitive dissonance. American Economic Review, 72, 307–319.

Alloy, L., & Abramson, L. (1979). Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: sadder but wiser. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 108(4), 441–485.

Babad, E. (1995). Can accurate knowledge reduce wishful thinking in voters’ predictions of election outcomes? Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary & Applied, 129(3), 285–300.

Babad, E., & Katz, Y. (1991). Wishful thinking—against all odds. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21(23), 1921–1938.

Barberis, N., Huang, M., & Santos, T. (2001). Prospect theory and asset prices. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 1–53.

Backus, D., Routledge, B., Zin, S. (2004). Exotic preferences for macroeconomists, NBER Working Paper 10597.

Barber, B.M., & Odean, T. (2008). All that glitters: the effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. Review of Financial Studies, 21(2), 785–818.

Baumeister, R., Campbell, J., Krueger, J., & Vohs, K. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(1), 1–44.

Bell, D. (1985). Disappointment in decision making under uncertainty. Operations Research, 33, 1–27.

Benabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2002). Self-confidence and personal motivation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 871–915.

Benabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Incentives and prosocial behavior. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1652–1678.

Benartzi, S., & Thaler, R. (1995). Myopic loss aversion and the equity premium puzzle. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(1), 73–92.

Bodner, R., & Prelec, D. (2001). Self-signaling and diagnostic utility in everyday decision making. In I. Brocas & J.D. Carrillo (Eds.), Collected essays in psychology and economics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brooks, P., & Zank, H. (2005). Loss averse behavior. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 31(3), 301–325.

Brunnermeier, M.K. & Parker, J.A. (2002). Optimal expectations. Princeton University, working paper.

Brock, T., & Balloun, J.L. (1967). Behavioral receptivity to dissonant information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6, 413–428.

Camerer, C. (1987). Do biases in probability judgment matter in markets? Experimental evidence. American Economic Review, 77(5), 981–997.

Camerer, C., Loewenstein, G., & Weber, M. (1989). The curse of knowledge in economic settings: an experimental analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 97, 1232–1254.

Caplin, A. (2003). Fear as a policy instrument. In G. Loewenstein, D. Read, & R. Baumeister (Eds.), Time and decision. New York: Russell Sage.

Caplin, A., & Leahy, J. (2001). Psychological expected utility theory and anticipatory feelings. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 51–80.

Constantinides, G. (1990). Habit formation: a resolution of the equity premium puzzle. Journal of Political Economy, 98, 519–543.

Cotton, J. (1985). Cognitive dissonance in selective exposure. In D. Zillmann, & J. Bryant (Eds.), Selective exposure to communication. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

DellaVigna, S., & Pollet, J.M. (2005). Investor inattention, firm reaction, and Friday earnings announcements. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=843786

Delquié, P., & Cillo, A. (2006). Disappointment without prior expectation: a unifying perspective on decision under risk. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 33(3), 197–215.

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 653–663.

Ehrilch, D., Guttman, I., Schonbach, P., & Mills, J. (1957). Postdecision exposure to relevant information. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 54, 98–102.

Epstein, L. & Zin, S. (1989). Substitution, risk aversion, and the temporal behavior of consumption and asset returns: A theoretical framework. Econometrica, 57, 937–969.

Epstein, S., Lipson, A., Holstein, C., & Huh, E. (1992). Irrational reactions to negative outcomes; evidence for two conceptual systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 328–339.

Festinger, L. (1964). Conflict, decision, and dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Freedman, J.L., & Sears, D.O. (1965). Warning, distraction, and resistance to influence. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 1(3), 262–266.

Frey, D., & Stahlberg, D. (1986). Selection of information after receiving more or less reliable self-threatening information. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 12(4), 434–441.

Galai, D., & Sade, O. (July 2003). The ‘ostrich effect’ and the relationship between the liquidity and the yields of financial assets, SSRN working paper.

Geanakoplos, J., Pearce, D., & Stacchetti, E. (1989). Psychological games and sequential rationality. Games and Economic Behavior, 1(1), 60–79.

Gneezy, U., & Potters, J. (1997). An experiment on risk taking and evaluation periods. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 631–645.

Griffin, J.M., Nardari, F., & Stulz, R.M. (2004). Stock market trading and market conditions. Working paper, McCombs School of Business, University of Texas at Austin.

Gul, F. (1991). A theory of disappointment aversion. Econometrica, 59(3), 667–686.

Horowitz, J., & McConnell, K. (2002). A review of WTA/WTP studies. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 44(3), 426–447.

Jonas, E., Schulz-Hardt, S., Frey, D., & Thelen, N. (2001). Confirmation bias in sequential information search after preliminary decisions: an expansion of dissonance theoretical research on selective exposure to information. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 80(4), 557–571.

Kahneman, D., & Lovallo, D. (1993). Timid choices and bold forecasts: a cognitive perspective on risk taking. Management Science, 39(1), 17–31.

Kahneman, D., & Miller, D. (1986). Norm theory: comparing reality to its alternatives. Psychological Review, 93(2), 136–153.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1982). The psychology of preferences. Scientific American, 246, 160–173.

Köszegi, B. (1999). Self-image and economic behavior, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, mimeo.

Köszegi, B., & Rabin, M. (2007). Reference-dependent consumption plans, University of California at Berkeley, mimeo.

Kreps, D., & Porteus, E. (1978). Temporal resolution of uncertainty and dynamic choice theory. Econometrica, 46, 185–200.

Kruglanski, A. (1996). Motivated social cognition: principles of the interface. In E.T. Higgins & A.W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498.

Loewenstein, G. (1985). Expectations and intertemporal choice. Yale University Department of Economics, doctoral dissertation.

Loewenstein, G. (1987). Anticipation and the valuation of delayed consumption. Economic Journal, 97, 666–684.

Loewenstein, G. (2006). Pleasures and pains of information. Science, 312, 704–706.

Loewenstein, G., & Adler, D. (1995). A bias in the prediction of tastes. Economic Journal, 105, 929–937.

Loewenstein, G., & Issacharoff, S. (1994). Source-dependence in the valuation of objects. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 7, 157–168.

Loewenstein, G., O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (2003). Projection bias in predicting future utility. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 1209–1248.

Loomes, G., & Sugden, R. (1986). Disappointment and dynamic consistency in choice under uncertainty. Review of Economic Studies, 53(2), 271–282.

Mellers, B.A., Schwartz, A., Ho, K., & Ritov, I. (1997). Decision affect theory: emotional reactions to the outcomes of risky options. Psychological Science, 8(6), 423–429.

Peterson, C., & Bossio, L.M. (2001). Optimism and physical well-being. In E.C. Change (Ed.), Optimism & pessimism: implications for theory, research, and practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Rabin, M. (1993). Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. American Economic Review, 83, 1281–1302.

Rabin, M., & Schrag, J. (1999). First impressions matter: a model of confirmatory bias. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(1), 37–82.

Routledge, B., & Zin, S. (2004). Generalized disappointment aversion and asset prices, NBER Working Paper w8683.

Sartre, J.P. (1953). The existential psychoanalysis (H.E. Barnes, trans.). New York: Philosophical Library.

Scheier, M., Carver, C., & Bridges, M. (2001). Optimism, pessimism, and psychological well-being. In E.C. Chang (Ed.), Optimism & pessimism: implications for theory, research, and practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Schneider, S. (2001). In search of realistic optimism: meaning, knowledge, and warm fuzziness. American Psychologist, 56, 250–263.

Shefrin, H., & Statman, M. (1984). Explaining investor preference for cash dividend. Journal of Financial Economics, 13(2), 253–282.

Shiller, R. (2006). Irrational exuberance (second edition). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Simonsohn, U., Karlsson, N., Loewenstein, G., & Ariely, D. (2008). The tree of experience in the forest of information: Overweighing experienced relative to observed information. Games and Economic Behavior, 62, 263–286.

Sloman, S. (1996). The empirical case for two systems of reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 3–22.

Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: the extended parallel process model, Communication Monographs 59. Available at http://www.msu.edu/~wittek/fearback.htm

Zeelenberg, M., van Dijk, W., Manstead, A., & van der Pligt, J. (2000). On bad decisions and disconfirmed expectancies: the psychology of regret and disappointment. Cognition and Emotion, 14, 521–541.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (STINT) and the Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation (grant K2001-0306) for supporting Karlsson and Loewenstein’s collaboration, Bjorn Andenas of the DnB Norway group, SEB, and the Swedish Premium Pension Fund for providing data. We are very grateful to Daniel McDonald for able research assistance. We thank Kip Viscusi (editor), two anonymous referees, and also On Amir, Nick Barberis, Roland Benabou, Stefano DellaVigna, John Griffin, Gur Huberman, John Leahy, Robert Shiller, Peter Thompson, Jason Zweig and seminar participants at the 2004 Yale International Center for Finance Behavioral Science Conference and at Case Western University for comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karlsson, N., Loewenstein, G. & Seppi, D. The ostrich effect: Selective attention to information. J Risk Uncertain 38, 95–115 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-009-9060-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-009-9060-6