Abstract

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) declared 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets to be achieved by 2030, but the COVID-19 pandemic has stalled the world’s progress in pursuing them. This article explores how the pandemic has impacted the public health and education sectors of the world’s poorest 46 countries, identified by the UN as “least developed countries” (LDCs). Applying the theoretical lens of international political economy, the author first considers the historical, political and economic causes behind the pre-pandemic underdevelopment of LDCs’ public health and education sectors. Next, he examines how the international support mechanisms forged in 2015 for the timely achievement of the SDGs have been affected by the pandemic, especially in the areas of health (SDG 3) and education (SDG 4). Based on a number of purposively selected international and national policy documents as well as a few related texts, the author uses the case of Nepal as an example to demonstrate what has particularly hampered LDCs’ sustainable development – and indeed continues to do so during the ongoing pandemic. He identifies three main adverse factors: (1) the privatisation of health and education; (2) a lack of governmental accountability; and (3) dysfunctional international support mechanisms. The article appeals for a more egalitarian global collaboration and full accountability of LDC governments in the joint effort to achieve a sustainable recovery from the pandemic.

Résumé

La pandémie de COVID-19, les Objectifs de développement durable en matière de santé et d’éducation et les « pays les moins avancés » comme le Népal – En 2015, l’Organisation des Nations unies (ONU) a défini 17 Objectifs de développement durable (ODD) et 169 cibles à atteindre d’ici 2030, mais la pandémie de COVID-19 a freiné les progrès réalisés au niveau mondial. Cet article explore l’impact de la pandémie sur les secteurs de la santé publique et de l’éducation dans les 46 pays les plus pauvres du monde, identifiés par l’ONU comme les « pays les moins avancés » (PMA). En appliquant l’approche théorique de l’économie politique internationale, l’auteur examine d’abord les causes historiques, politiques et économiques du sous-développement des secteurs de la santé publique et de l’éducation dans les PMA avant la pandémie. Ensuite, il examine comment les mécanismes de soutien international forgés en 2015 pour la réalisation des ODD ont été affectés par la pandémie, en particulier dans les domaines de la santé (ODD 3) et de l’éducation (ODD 4). En s’appuyant sur un certain nombre de documents de politique internationale et nationale sélectionnés à propos, ainsi que de quelques textes additionnels, l’auteur utilise le cas du Népal pour illustrer ce qui a particulièrement entravé le développement durable des PMA – et continue de l’entraver pendant la pandémie en cours. Il identifie trois principaux facteurs défavorables : (1) la privatisation de la santé et de l’éducation ; (2) le manque de responsabilité gouvernementale ; et (3) le dysfonctionnement des mécanismes de soutien international. L’article lance un appel en faveur d’une collaboration mondiale plus égalitaire et d’une responsabilisation totale des gouvernements des PMA dans l’effort commun pour parvenir à une reprise durable suite à la pandémie.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Even though infection and death rates were much higher in developed countries in 2020 than in developing countries, since early 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic has definitely exacerbated the problems of the world’s developing countries that they were already struggling with in pre-pandemic times. The purpose of this articleFootnote 1 is to explore the impact of the pandemic on “least developed countries” (LDCs), a group of 46 countries identified by the United Nations (UN) using economic, human development and vulnerability indexes (CDP 2021a). LDCs account for 12% of the world population but share less than 2% of the global gross domestic product (GDP) (Bhattacharya and Islam 2020). In LDCs, poverty (in 2019, 53% of the population lived on less than USD 1.90 per day), illiteracy (60% of the population cannot read and write), low life expectancy (on average, people expect to live only 65 years), and low economic productivity (USD 1,125 GDP per capita) as well as climate change hazards are major problems, which have made them the most vulnerable countries in the world (UNDP 2019; UNCTAD 2020a). Early COVID-19 impact assessment reports demonstrate that LDCs are “undergoing the worst recession in 30 years” (UNCTAD 2020a, p. xv). Therefore, if drastic policy measures are not taken, the existing problems will continue to worsen, and these countries may never recover from the pandemic (UN-OHRLLS 2020). Since quality education is a fundamental prerequisite for achieving all 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations 2030 Agenda (UN 2015a), post-pandemic recovery plans need to focus on SDG 4, which is dedicated to improving access to lifelong learning and education. While the predicament brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic is having a disastrous impact on all sectors, the public education sector is experiencing a particularly damaging long-term impact due to the introduction of “social distancing” measures required for mitigating the spread of the virus, particularly at the beginning of the pandemic, when vaccines were not yet available.

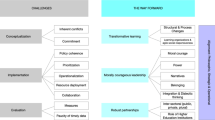

The Centre for Development Policy (CDP), which is mandated by the UN General Assembly (UNGA) and the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) to review the list of LDCs every three years, uses three criteria for identifying LDCs – the human assets index (HAI), the per capita gross national income (GNI), and the economic and environmental vulnerability index (EVI).Footnote 2 The criteria measuring health (under-five mortality rate, prevalence of stunting and maternal mortality ratio) and education (gross secondary school enrolment ratio, adult literacy rate and gender parity index for gross secondary school enrolment) fall under the HAI (see Figure 1).

Source: CDP (2021b, p. 64)

Health- and education-related criteria for identifying LDCs.

In the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to stress that the 46 countries currently in the UN’s LDC category (see Table 1) are included there because they rank the lowest in health and education indices among all the countries of the world. Since literate individuals are likely to be healthier than those who have low or no literacy, including an education index among the criteria for identifying LDCs is significant. Healthy citizens are more likely to understand the importance of infection prevention measures, participate in lifelong learning, raise their children with good care and support, and contribute to the labour market by being more efficient in their workplaces than less healthy citizens (Rubenson and Desjardins 2009). Unfortunately, because of the measures introduced to curb the spread of the coronavirus, such as social distancing and school closures enforced by national governments, public education was – and still is – the sector most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in LDCs.

Public health and education systems managed by a country’s national government are critical for building and bolstering that country’s sustainable socioeconomic and democratic foundation (Polanyi 2001 [1944]; Piketty 2020). A country of healthy and literate citizens has a better chance of promoting national policies which are oriented towards sustainability than a country lagging behind in terms of health and education. Therefore, “human assets” related to health and education are not only relevant for identifying LDCs (see Figure 1) but also for achieving the SDGs by 2030 (UN 2015a). For example, SDG 3 on health aims to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” (UN 2015a, p. 16). This goal includes targets such as achieving “access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all” (SDG Target 3.8; UN 2015a, p. 16) – this is particularly relevant to LDCs. Similarly, SDG 4 on education aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” (UN 2015a, p. 14). Since public health and education reinforce each other in a country’s sustainable development, both SDG 3 and SDG 4 need renewed attention in all post-pandemic plans and policies. This article aims to investigate the status of public health and education in LDCs, using the case of Nepal as an example and focusing on the following research questions:

-

What are the historical, political and economic causes behind the underdevelopment of LDCs’ public health and education sectors?

-

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the international support mechanisms forged for achieving the 17 SDGs of the 2030 Agenda in terms of promoting public health and education?

This article is organised into four main sections. The first section presents a review of scholarly literature on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the public health and education sectors. The second section considers post-World War II political and economic history and its impact on LDCs’ public policies. The third section describes this study’s methodological approach in exploring the historical causes of LDCs’ underdevelopment using the case of Nepal as an example. The fourth section presents the key findings and their analysis in three subsections: privatisation of health and education, lack of accountability, and dysfunctional international collaborations. The article ends with a brief discussion of the key findings of the study and draws a few conclusions.

The impact of the pandemic: a literature review

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the world in early 2020, soon prompting a proliferation of scholarly publications grappling with the experience and trying to gauge the long-term consequences. A number of these publications are helpful for understanding how the pandemic has affected the public health and education sectors around the world. They have focused mainly on three broad areas: inequality, technology and the SDGs.

Henrique Lopes, a professor of public health, and Veronica McKay, an adult educator and former Chief Executive Officer of the South African Literacy Campaign, co-authored an article on “Adult learning and education as a tool to contain pandemics: The COVID-19 experience” (Lopes and McKay 2020). The International Review of Education published two double special issues on “Education in the age of COVID-19”. The first one was subtitled “understanding the consequences” (see Stanistreet et al. 2020), and the second one considered the “implications for the future” (see Stanistreet et al. 2021). The latter includes an article by Kamal Raj Devkota on “Inequalities reinforced through online and distance education in the age of COVID-19: The case of higher education in Nepal” (Devkota 2021). Michelle Kaffenberger, anticipating potential long-term consequences of the pandemic, measured the extent to which school closures have caused learning loss among grade 3Footnote 3 students of low- and middle-income countries. Modelling different scenarios, she found that, by the time the affected grade 3 students reach grade 10, their learning on average will be “a full year lower than what it would have been had there been no shock” (Kaffenberger 2021, p. 4; italics in original).

Several scholars have examined the extent to which the increased use of technology has mitigated the learning loss caused by the pandemic. For example, Dhruba Kumar Gautam and Prakash Kumar Gautam analysed the perception of faculty members and higher education students about the online mode of teaching adopted by Nepal during the COVID-19 pandemic; they found that the effectiveness of online classes depended on three main factors: infrastructure, students and teachers (Gautam and Gautam 2021). Isma Seetal et al. (2021) found that in Small Island Developing States (SIDS), a designation referring to a group of developing countries with a number of distinctive vulnerabilities, learning loss occurred because teachers “lacked adequate training” in using technologies (Seetal et al. 2021, p. 185).

In addition to those that have focused on inequality and technology, many publications have explored the impact of the pandemic on the timely achievement of the SDGs. For example, Luis Fernández-Portillo et al. (2020) undertook a content analysis of international policy documents written by 15 think tanks such as the Institute of Development Studies and Brookings Institution to explore how the pandemic is affecting the timely achievement of the 2030 Agenda (UN 2015a). They not only emphasise the importance of global cooperation for achieving the SDGs, but also caution that emerging issues such as the trade embargo between China and the United States (US), vaccine nationalism and significant cuts in bilateral funding for developing countries will have an adverse impact on poor countries. Similar observations are made by Lynette Shultz and Melody Viczko (2021), who argue that supranational organisations have endorsed tech corporations as saviours of failing education systems, but ignored the role of national governments.

Some studies have focused particularly on the importance of the global collaboration for achieving the SDGs. For example, Richard Kozul-Wright argues that the world needs an expansionary multilateral plan for global recovery “that can credibly return even the most vulnerable countries to a stronger position than before the crisis” (Kozul-Wright 2020, p. 157). Focusing especially on LDCs, Giovanni Valensisi investigated the potential fallout from the pandemic on SDG 1 on poverty reduction. He argues that the pandemic will “trigger adverse long-term effects and create path-dependency from transient poverty into chronic poverty” (Valensisi 2020, p. 1540); therefore, “future prospects are partly contingent on the policy responses adopted at national and international levels” (ibid.). Davida Smyth (2020) also found that the pandemic would push millions of people into poverty and highlights the need for a renewed focus on the timely achievement of the SDGs.

A key message emerging from this literature review is that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health and education is more severe in LDCs than many other countries because of the problems and challenges they were already saddled with when the pandemic arrived. While all the publications reviewed above are helpful for understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a serious lack of research literature focusing on the historical, political and economic causes behind the underdevelopment of LDCs’ health and education sectors – an aspect which has gained in relevance in the current situation. This article therefore aims to fill that gap in the existing body of literature.

The origins of LDCs’ public policies

A review of theoretical literature on political economy (Hayek 1944; Polanyi 2001 [1944]; Friedman 1955; Rodrik 2011; Steil 2013; Kissinger 2014; Piketty 2020) shows that the production of useful, fit-for-purpose public policies and their effective implementation require a delicate compromise between a strong, capable government and the freedom of the market. If governments are given too much power, protectionism, petty nationalism and fascism is likely to rise. If the market is given too much freedom, the private sector is bound to take over public institutions, and vital social services related to health and education will be available only to those who can afford them.

The debate on whether a strong democratic government or the freedom of the market would help countries achieve prosperity was at its peak during the mid-1940s. In July 1944, the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference was held in Breton Woods, New Hampshire, to discuss the creation of what became known as “the Bretton Woods Institutions” (BWIs): the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), now known as the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), both established in 1944, as well as an international trade organisation.Footnote 4 Among the delegates of 44 countries who participated in the conference, John Maynard Keynes from the United Kingdom (UK), and Harry Dexter White from the US (who believed in Friedrich Hayek’s economic theory)Footnote 5 came with competing proposals. While Keynes argued that for post-war global peace to be durable, the envisaged global financial institutions should “allow governments more power over markets” (Steil 2013, p. 1), the proposal of the US delegates accorded more freedom to the market (Hayek 1944; Friedman 1955). The latter won out (Boughton 2002) and provided the foundation for the Bretton Woods Agreements.

Another relevant entity was the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC), created in 1948 and reconstituted as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 1961. Its initial purpose was to coordinate efforts to restore Europe’s economy in the immediate aftermath of World War II. Later on, especially during the 1960s and the 1970s, the governments of developed OECD member countries maintained a certain level of social equality by implementing welfare policies (Piketty 2020). But the majority of LDCs, first identified as such by the UN in 1971, did not have any welfare policies. Having only just gained independence from their colonisers, these countries had more pressing problems such as a lack of democracy, an absence of modern infrastructure, as well as illiteracy and poverty (Martin 1972). The debate about whether a stronger democratic government or the creation of a free functioning market should be prioritised for the benefit of LDCs was beyond the purview of national policymakers and planners. Guided by the modernist ideology of “development”, instead of exploring what policies would solve LDCs’ contextual challenges, they relied on policies prescribed by bilateral and multilateral organisations.

The World Health Organisation (WHO), established in 1948, and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), established in 1945, were mandated to promote public health and education in developing countries. As multilateral UN institutions, they were expected to collaborate with governments to modernise their health and education sectors. Unfortunately, however, the effectiveness of WHO and UNESCO was limited, especially after the 1980s, because both lacked financial support, which had to be secured mostly from developed countries (Mundy 2006). Unlike WHO and UNESCO, the Bretton Woods Institutions were backed by market forces; they thus held monetary power, and came to fill the leadership vacuum. Instead of supporting national governments in controlling corruption and institutionalising democracy, the Bretton Woods Institutions approached the public health and education sectors of LDCs through the market mechanism (Pleines 2021). Governments of LDCs were asked to adopt market-friendly policies under so-called “structural adjustment programmes” (SAPs).Footnote 6 Multilateral mechanisms created in the post-war period to promote welfare policies and practices in LDCs were replaced almost completely after the 1980s by a neoliberal market mechanism (Martin 1972).

Meanwhile, under current neoliberalism, the agenda of creating a strong democratically elected government in LDCs has been replaced by the agenda of setting up a free market, privatising public sectors such as health and education, and eliminating national policy barriers for multinational corporations to finance, manage and govern these countries’ health and education sectors. By using multilateral mechanisms such as the “Communication” from the World Trade Organization (WTO) delegation of the United States on education, developed countries have asked LDCs

to help create conditions favorable to suppliers of higher education, adult education, and training services by removing and reducing obstacles to the transmission of such services across national borders (WTO 2000, pp. 1–2).

These mechanisms have not only increased privatisation within individual LDCs but also provided multinational corporations with unrestricted freedom for the establishment and operation of private schools, universities and hospitals.

The case of Nepal as an LDC

After Nepal gained independence from the internal colonisation of the autocratic Rana regime in the early 1950s, the involvement of foreign donors in the country’s political, economic and educational affairs gradually intensified. During the 1970s, the government led by King Mahendra nationalised Nepal’s education system, a move which increased the power of the government (GoN 1971). The governance, management and financing of preschool, primary and secondary (K–12) and higher education of Nepal were thus controlled by the central government, which resisted the privatisation of education. But after the 1980s, several supranational organisations including the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and other bilateral organisations led by the US, UK and the European Union (EU) got involved in the governance and financing of Nepal’s education and health systems (Regmi 2021, 2015). The government lost its mandate as an accountable agency to ensure quality education and basic health of its citizens. Consequently, hospitals and schools operated by the private sector replaced government-owned hospitals and schools especially after the 1990s (GoN 1992, 2016).Footnote 7

Due to its geographical situation, Nepal is unfortunately prone to landslides, floods and earthquakes. Because of the 2015 earthquake (NPC Nepal 2015), fluctuations in remittance inflows, and the impact of climate change on food production, Nepal’s economic growth has been very uneven. It was 0.6% in 2016, which increased to 8.2% in 2017, but then plunged to 2.5% in 2020 (MoF Nepal 2020, p. 2). The outstanding public debt of the federal government currently stands at 30.30% of Nepal’s GDP (ibid., p. 23). A major problem is the Government of Nepal’s incapacity to increase capital expenditure, which includes investment in infrastructural items such as roads, school buildings, bridges, dams and airports. In the fiscal year July 2019–June 2020, it took the Government of Nepal six months to spend 15.8% (ibid., p. 25) of the total budget. The provincial governments managed to spend only 20% of their total budget in eight months (ibid., p. 39).

Nepal has a population of about 30 million, but due to a shortage of jobs, about 5 million (of whom about 40% are women) have left the country to work abroad (MoF Nepal 2020, p. 63). It is unfortunate that only 1.5% of those 5 million people are skilled workers, whereas 24.0% are semi-skilled, and 74.5% are unskilled who are underemployed and underpaid (ibid.). One of the saddest parts of foreign employment has been the mortality of migrant workers, mainly because of their lack of a health insurance. In the first eight months of the fiscal year 2019/2020, about 600 Nepali people died during foreign employment (ibid., p. 65). Despite the “Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage” (UN 2019), Nepalese migrant workers’ health insurance is covered neither by their employers abroad nor by the Government of Nepal. While remittances sent home by those migrant workers – amounting to 25% of GDP for the past 10 years – have supported the economy, the trade deficit has increased significantly (UNCTAD 2020a). During the period from May 2020 to June 2021, the GDP share of imports was 91.94%, while exports stood at merely 8.06% (MoF Nepal 2020).

Since Nepal was identified as an LDC in 1971, the desire for graduation to a developing country has shaped major plans made by the National Planning Commission, bringing about key policies to improve health (GoN 1991, 1997, 2014) and education (GoN 1992, 2016). While Nepal did meet LDC graduation criteria in the 2015 triennial review conducted by the Centre for Development Policy, in the 2018 review graduation was deferred until 2021 because of the setback caused by the 2015 Nepal earthquake (NPC Nepal 2015). Because of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2021 triennial review made a “horizontal” recommendation, which means that Nepal has an extended five-year preparatory period towards graduation. If progress towards graduation indicators is successful and the targets are met, Nepal will graduate from the LDC category by 2026 (CDP 2021a).

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Nepal

Nepal reported its first COVID-19 positive case on 13 January 2020 (Bastola et al. 2020). With about 9,000 confirmed COVID-19-related deaths by June 2021 (Our World in Data 2021), it remained one of the worst-affected Asian LDCs in 2021 (see Figure 2).Footnote 8 Prajwal Neupane et al. comment:

Providing quality health care during the COVID-19 pandemic has been challenging and such care is limited to only a few people. … In the context of Nepal, factors such as poverty, illiteracy, lack of infrastructure, shortage of health care professionals, attitude towards medical professionals, security concerns of health care professionals, health insurance policies, geographic distribution, culture, governmental policies, and physical barriers also directly affect health care services being provided (Neupane et al. 2021, p. 2).

Source: Our World in Data (2021)

COVID-19 pandemic in Asian LDCs (status 30 June 2021).

The impact of the pandemic on school and higher education was also severe because of the lack of technological access (Devkota 2021). There are 29,607 community schools in Nepal, but only 8,366 schools had computers until March 2020 and only 3,676 schools were able to use instructional technologies (MoF Nepal 2020). Some privately-owned schools, most of which are in urban centres, are equipped with instructional technology. While they are often appreciated as venues for quality education, the pandemic forced these schools to take some drastic measures such as staff layoffs and school shutdowns (ibid.).

In the last few years, primary school enrolment (97.1% in 2019) and gender equality rates increased (UNDP 2019), but dropout rates remain high at secondary level because of poverty, economic hardships, lack of secondary schools in students’ neighbourhoods, and early marriages of girls (GoN 2016). In 2019, only 60.3% of students enrolled in Nepalese schools reached grade 10, and just 24% made it to grade 12 (MoF Nepal 2020).Footnote 9 The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened this situation because children from low socioeconomic backgrounds are affected the most.

Methodology

Informed by the review of scholarly publications and the broader political and economic history outlined above, this qualitative study is based on data extracted from policy documents produced by international organisations and the Government of Nepal (GoN).

Analysing these policies from a historical perspective, a method also referred to as policy historiography (Gale 2001), and using Nepal as an example, this article explores how the capacity of LDCs to address current challenges related to the impact of the pandemic on public health and education is determined by policy decisions made in the past. Policies reflect priorities set by those who were in power at the time of adoption; however, the policymakers’ decisions are guided by political and economic interests. Policymakers working at local, national and global levels promote certain policies but supress others, which is largely due to power dynamics among stakeholders. In the context of globalisation, LDCs’ policies on public health and education are shaped by the political ideology of individual national governments, economic interests of for-profit philanthropies, supranational organisations, and corporations (Rizvi and Lingard 2010).

By critically analysing policy documents, my aim in this study is to “spea[k] to and/or against elite actors, networks and power” (Savage et al. 2021, p. 6). Policy transfer, mainly from donors to recipient countries, is not a new phenomenon. However, in the context of the global pandemic, key measures such as social distancing, school closures and online instruction have created a new environment of policymaking and implementation. I purposively selected about 25 relevant documents by using two inclusive criteria: policy documents related to LDCs; and policies relevant to public health and education. In terms of their origins, they fall into two groups: (1) supranational organisations’ policy documents and related items, and (2) policy documents produced by the Government of Nepal and its line agencies. A list of the purposively selected documents is provided in Table 2.

As Sharan Merriam and Elizabeth Tisdell note, “data analysis is the process of making sense of the data” (Merriam and Tisdell 2016, p. 202). I read the selected policy documents several times, highlighting sentences and paragraphs, and made some notes in light of the research questions. I also factored in key takeaways I had obtained by reviewing the scholarly publications as mentioned in the literature review section, as well as the historical, political and economic contextual origins of LDCs’ public policies discussed above.

By re-reading those highlights and notes I was able to identify policies mentioned in those documents that were “responsive” (Merriam and Tisdell 2016, p. 203) to my research questions. To identify how policies developed by supranational organisations affected the policies developed by LDCs, I organised the selected quotes both “chronologically” and “thematically” (ibid., p. 215). The themes I developed for organising those quotes and their interpretations were informed by my research questions, theoretical considerations, and my review of scholarly publications.

Analysis and findings

In this section, I present the key findings of my study. The historical evolution of the current situation points to the political and economic cause of the underdevelopment of LDCs’ public health and education being the “structural adjustment” policy imposed by the World Bank and the IMF during the 1980s. Instead of generating healthy development and improvement on HAI indicators (shown in Figure 1), the loans accepted consolidated and perpetuated external, market-oriented governance. The lack of LDC governments’ own policies resulted in rising unemployment. Millions of youths and young adults have left their country for a livelihood as temporary migrant workers but, as they lack necessary skills and training, their jobs are insecure, and they are underemployed and underpaid. This already precarious situation was further exacerbated when remittances sent home by migrant workers were significantly reduced as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold. Thus, the socioeconomic repercussions of the pandemic on LDCs are severe.

Since the creation of strong and democratic governments, which take responsibility for effective planning for the development of public health and education systems, was not prioritised in LDCs in the post-war period, the private sector started making investments. In more recent decades, especially under neoliberal globalisation, multinational corporations have been encouraged to finance, manage and govern public health and education sectors. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the international collaboration forged between Bretton Woods Institutions, multinational corporations and governments of LDCs became dysfunctional because developed countries were engaged in their own internal affairs for addressing the new challenges brought by the pandemic. Below, I elaborate these findings and arguments, taking a closer look at (1) the privatisation of health and education in LDCs more generally and in Nepal in particular; (2) the lack of accountability; and (3) dysfunctional international collaboration.

Privatisation of health and education

LDCs’ healthcare and education sectors are being increasingly privatised, which warrants a critical policy analysis from a historical perspective (Gale 2001). In the post-war period, many LDCs freed from colonial rule had increased public funding on health and education. For example, both King Mahendra in Nepal (see GoN 1971) and President Julius Nyerere in Tanzania (Nyerere 1968) gave a significant boost to the amount of public funding for education. But the oil crisis of the early 1970s and internal conflicts affected their countries’ economies, which eventually led them to seek loans from international banks and lenders (McMichael 2012). Because of the increasing inflation of their respective national currencies, both countries defaulted on those loans in the late 1970s. This repayment failure was interpreted by the World Bank’s economists as being due to structural problems. The solution prescribed by them was for LDCs to adjust the way they spent their annual revenues (Mundy 2006). Based on this logic, structural adjustment policies were implemented in LDCs during the 1980s (McMichael 2012).

To comply with these externally imposed structural adjustment policies, LDCs had to “reduce public spending” (UN 2020a, p. 14), especially in the domains of health and education, and invest in those sectors that would yield profitable monetary returns so that they could pay back their debts to international banks, lenders and creditors (UNDP 2011). For example, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, “the education sector virtually disappeared from the state budget” from the 1980s onwards (De Herdt and Titeca 2016, p. 473). In Nepal, as the expansion of public health and education sectors stalled, new policies on health (GoN 1991, 1997) and education (GoN 1992, 2016) were made to encourage the private sector and foreign donors to establish hospitals and schools with no restrictions for making profit. Under the WTO regime, LDCs were asked to allow multinational corporations to make unrestricted investment in their health and education sectors (WTO 2000).

Supported by neoliberal reforms such as public–private partnerships at the global level, private investors are now regarded as new stakeholders in policymaking, financing, and management of health and education (Shultz and Viczko 2021). In Nepal, “new private health institutions including academic institutions” (GoN 2014, p. 3) cater to the needs of the elite class, which includes political leaders, bankers, top-level bureaucrats, businesspeople, and the top-level employees of international institutions. Consequently, the deepening of already existing inequalities in LDCs have been further accelerated. For example, in 2018, wealth inequality between the top 10% of the population and the remaining 90% was higher in sub-Saharan Africa (the region that has 33 LDCs) than in the world’s major economies such as the US, Russia, China and Europe (Piketty 2020). While the top 10% of US citizens owned 48% of the national income, in sub-Saharan Africa the top 10% owned 54% of the national income (ibid.).

The pandemic has exposed the harm done by the policies implemented in the past, but it is the public who are forced to pay the price. In Nepal, private hospitals refused to admit COVID-19 patients, and several private schools were shut down, the teachers and other staff were either laid off or deprived of their salaries (ILO 2020). The pandemic is used as a proxy excuse for the governments of LDCs as Nepal to request more loans (see IMF 2020), but the harmful policies made in the past are not problematised. While Nepal’s policies which allowed the privatisation of its health and education system (GoN 1991, 1992, 2014, 2016) have been critiqued (Regmi 2021), they were not changed in subsequent policies because they are still backed by neoliberal policy reform agendas of the Bretton Woods Institutions.

Guided by market fundamentalism, many political leaders and international lenders assume that privatisation is a good alternative to failing public health and education systems in LDCs (De Herdt and Titeca 2016). They believe that privatisation generates revenues without burdening governments in terms of financing, management, monitoring and supervision (Hayek 1944; Friedman 1955). But the pandemic has exposed the limit of the market as the health sector struggled with rapidly rising COVID-19 infections.

The inequalities between OECD member countries and LDCs in terms of both health (see Figure 3) and education (discussed below) are huge. In comparison to OECD countries, there are fewer hospitals, nurses, midwives and doctors in LDCs. The lack of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), ventilators, oxygen cylinders and Intensive Care Units (ICUs) made what was already a precarious situation worse during the pandemic. A survey undertaken in 2020 in selected LDCs (Chowdhury and Jomo 2020) found that only about a third of health centres in Bangladesh, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nepal and Tanzania had face masks. In Zambia, the Gambia and Uganda, the ICU beds (per 100,000 population) were 0.6, 0.4 and 0.1, respectively, compared to the OECD average of 12 (OECD 2020).

Source: UNDP (2019)

Number of hospitals and healthcare workers per 1,000 population (LDCs vs OECD member countries).

LDCs’ education sector is affected as much as their health sector. Teaching–learning activities in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (the regions where the majority of LDCs are located), came to a standstill during the pandemic because of a lack of electricity, computers and internet infrastructure (Seetal et al. 2021). Educational institutions were unable to move to online instruction because only about 18% of the population in LDCs have access to the internet (Bhattacharya and Islam 2020).

The case of Nepal shows that parents are not able to pay for materials needed for their children’s tuition, let alone afford computers and internet data. A few elite private schools have managed to deliver online instruction, but most of them are closed. Out of about 30,000 public schools in Nepal, only 8,000 have computers, and fewer than 12% of the total number of schools (i.e. public plus private) have internet connection (MoF Nepal 2020). Furthermore, in many countries, especially LDCs, the government’s decision to move to online instruction has forced poor parents to stretch their meagre financial means to buy smartphones, computers, tablets, instructional software and internet data, but even for those with access to technical tools, learning has not happened, since many students and teachers lack skills to use online instructional platforms (Seetal et al. 2021).

Lack of accountability

Accountability – being answerable for fulfilling one’s responsibilities – may refer to compliance with regulations, adherence to professional norms and/or results-based management. In the current mechanism of global governance, the notion of accountability is mostly tied to results-based management; therefore, the success of education systems is measured in terms of the performance of students, teachers and school leaders in standardised testing such as the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). As Heinz-Dieter Meyer et al. point out, the idea of accountability, as a key tenet of democratic governance in its original sense, should focus on “keeping leaders accountable” (Meyer et al. 2014, p. 3) whose performance should be scrutinised by citizens through fair elections. By contrast, educational accountability, which has “emerged as the master rationale for contemporary education reform”, has been used to assess the performance of students, teachers, school leaders and even parents “based on predetermined indicators that are insensitive to the great variance of people, publics, and places” (ibid.).

The current accountability regime, “rooted in ideas about the superiority of market mechanisms that are contested in many [OECD] member nations” (Meyer 2014, p. 1), bolsters the power of multinational corporations while governments of LDCs are made (or are willing to be) responsible for opening their health and education sectors to international markets. The OECD and the Bretton Woods Institutions do not hold “governments accountable for their steering role in public education” (Meyer 2014, p. 2); rather, schools, teachers and students are held accountable for failing education systems. Under this new accountability regime, multistakeholderism is promoted with an increased emphasis on achieving the goals of the 2030 Agenda (Gleckman 2018).

The governments of LDCs have accepted multistakeholderism for three basic reasons. First, LDC governments do not have enough budget to plan and run their own development programmes – which would also include health and education programmes; therefore, they need foreign investment. Second, political leaders who hold government portfolios benefit personally because their collaboration and networking with the owners of multinational corporations will help them to win the next elections. Third, multistakeholderism allows political leaders to evade being held accountable for the failing education system. When multiple stakeholders are involved, no one is held fully accountable because each of them will manufacture a rationale to blame another stakeholder (Regmi 2021).

Multistakeholderism has resulted in the emergence of a new elite class which includes political leaders and the owners of multinational corporations. In this new global governance mechanism, national governments and intergovernmental bodies such as the UN make policies to hand over leadership roles to multinational corporations (Gleckman 2018). For example, when the UN General Assembly adopted its 2030 Agenda with its 17 SDGs in 2015, “governments formally committed themselves to enhanc[ing] the global partnership for sustainable development” (ibid., p. xii). LDC governments thus become “accountable” – not to their own people, but to external stakeholders – for ensuring that they have changed national policies to create an investment-friendly market for multinational corporations which are now known as “development partners”. They are expected to be neither democratically strong nor responsible for providing health and education services to their citizens. As Harris Gleckman (2018) argues, this new development has posed a challenge both to post-war multilateralism and democracy.

The lack of accountability has resulted in policy implementation failures. LDCs such as Nepal do have several viable health and education policies; some of which were made by their own governments (such as GoN 1971, 1991, 1992, 1997, 2014, 2016) and some of which were agreed through UN conventions (UN 2000, 2001; UNESCO 2011; UN 2015a, 2020a). However, most of these policies have not been implemented because the governments do not consider themselves fully accountable. Instead, failing healthcare and education systems are used as a rationale for making new policies and setting new goals. For example, even if almost all LDCs failed to achieve Education for All 2015 goals (WEF 2000), they are now expected to achieve Education 2030 goals (WEF 2016) without investigating the extent to which LDC governments might be accountable for implementation failures of the previous agenda.

In terms of generating a skilled workforce, LDC governments are not able to provide education and training to match the human resources needs of their countries, therefore, their citizens rely on the informal economy for their livelihood, which involves a lot of manual labour (ILO 2020; UNCTAD 2020b). The pandemic response measures such as lockdown, quarantine, sanitation and social distancing regimes adopted by developed countries were not suitable for supporting informal economies (Chowdhury and Jomo 2020; UN 2020b). Neither were these countries able to offer the kind of stimulus packages created by their developed counterparts for sustaining extended periods of lockdowns and quarantines (UN-OHRLLS 2020; UNCTAD 2020b). Since the socioeconomic repercussions of the pandemic are substantial, they have a cascading effect on public health and education. Those who were already marginalised, such as women and families from low socioeconomic backgrounds, have suffered the most.

In LDCs’ rural villages, people work on farms, share houses (average household occupancy in LDCs is 5), water taps, bedrooms and sanitary facilities (UNCTAD 2020b). The majority of the elderly people look after their grandchildren while adults remain busy with daily chores such as planting, harvesting and fishing, dependent on the changes in seasons and weather patterns (ILO 2020). Some adults who do not have farms or any other means of local income have temporarily migrated to cities to work for daily wages. Without this regular income, they would be unable to afford basic healthcare and education of their children. In recent decades, more formalised employment sectors such as ecotourism, community-based homestays, and small entrepreneurships have emerged as a major source of income. These sectors have been seriously affected by the pandemic. In Bangladesh, for example, one of the largest LDCs in terms of population, millions of youths who were employed in garment factories lost their jobs (UNCTAD 2020b).

Because of climate change and the increasing marketisation/urbanisation of LDC communities, members of poor families who used to survive on subsistence farming and fishing have sought salaried jobs. As LDC governments are not able to create jobs, young people have migrated to foreign countries as temporary workers (ILO 2020). The remittances they send home have contributed to their families’ survival (UN 2020a). Unfortunately, millions of migrant workers were laid off during the pandemic. Because of lockdowns, cancellations of international flights and border closures, they could neither return to their home countries nor send money to support their families. As noted above, a significant portion of LDCs’ GDP is generated from temporary workers’ remittances; however, with the impact of the pandemic, it is likely that the demand for migrant workers will continue to be low for years to come.

Dysfunctional international collaboration

International collaboration has become dysfunctional because multilateral institutions established after World War II – the UN and its sister organisations, and the Bretton Woods Institutions – have shifted from their original mandates (Stiglitz 2003). Today, they increasingly collaborate with multinational corporations that hold significant stakes in the global economy. According to Gleckman,

in multilateralism, governments, as representative of their citizens, take the final decisions on global issues and direct international organisations to implement these decisions. In multistakeholderism, stakeholders become the central actors. Decision-making and the implementation of these global decisions are often disconnected from the intergovernmental sphere (Gleckman 2018, p. xiii).

For example, multinational corporations were given privileged access to the UN meetings organised for deciding on the SDGs' financing modalities; therefore, public–private partnership became a new strategy for “planning, contract negotiation, management, accounting, and budgeting” (UN 2015b, p. 25).

In November 2020, the world’s top 20 economies, known as G20, held their annual summit meeting online (instead of in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, as originally planned). Several leaders, including Angela Merkel (Germany) and Justin Trudeau (Canada), expressed the importance of equitable global access to COVID-19 vaccines, but the summit ended without taking any binding measures. In June 2021, leaders meeting at the G7 inter-governmental political forum held in Carbis Bay, Cornwall, UK, reiterated that they would help to produce a billion dosages of COVID-19 vaccine for developing countries as a “building back better health security” initiative, but did not provide any details or sign any agreement about who would provide funding for purchasing the vaccines. They stated that they would donate vaccines to Covax, a WHO initiative created to purchase vaccines for poor countries, but many of them, for example Canada, only returned the number of dosages they had obtained from the Covax facility. While Covax remains “severely underfunded” (OECD 2021), developed countries, “including the US, as well as the European Union” have misused international law on patents and prevented developing countries from manufacturing vaccines (BBC News 2021). Vaccine capitalism combined with vaccine nationalism have compounded the inequalities which already existed between LDCs and developed countries before the onset of the pandemic (see Figure 4).

Source: UNDP (2019)

Inequality between LDCs and the OECD member countries.

Rather than increasing the amount of Official Development Assistance (ODA) to LDCs (OECD 2021), the international community, especially the World Bank, has urged LDC governments that they should engage with the private sector for enhancing their vaccination capacity (Evans and Pablos-Méndez 2020). In an interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), David Malpass, the current president of the World Bank, confirmed that the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a sister organisation of the World Bank, would fund the private sector to produce vaccines (CBC News 2021). Instead of ending the patent rights on COVID-19 vaccines held by multinational pharmaceutical companies, the World Bank aimed to lend money to the private sector to purchase licenses for the production and distribution of vaccines (Pleines 2021). While it was not certain whether poor LDC citizens would get vaccines on time, this development is definitely contributing to further privatising their health sector and increase their national debt.

As noted by previous researchers, pandemic recovery efforts not only require mass production of vaccines, but also their patent freedom, and fair distribution and availability to all (Chowdhury and Jomo 2020; Evans and Pablos-Méndez 2020). Moreover, it was also time to declare access to vaccines for COVID-19 – as well as possible future pandemics – a fundamental human right. The consequence of failing to consider obtaining the pandemic vaccine a human right, and failing to get the people living in remote parts of LDCs vaccinated on time, would be that the COVID-19 pathogen, in the same or a mutated form, would continue to hit the world with bigger waves. While it is important to allow a healthy competition among pharmaceutical companies to develop more effective vaccines, they should not be allowed to exploit the situation and reap profit. Although the leaders of 140 countries including China, Germany, France, Italy and Norway pledged at the 73rd World Health Assembly, held online 9–14 November 2020, that vaccines developed in their countries would be considered as a global public good, they did not take any binding measures (Chowdhury and Jomo 2020). For the timely prevention and mitigation of and recovery from the global crisis, a renewed global collaboration and consensus is a must, especially in LDCs (UN 2001).

Discussion and conclusion

The category of LDCs was conceived during the 1970s to channel special support measures from donor countries as their contribution to global social welfare (Martin 1972; CDP 2008). In major global agreements, the international community (mainly the UN, Bretton Woods Institutions and the OECD) affirmed that they would help LDCs to catch up with developed countries through bilateral and multilateral mechanisms (Martin 1972; UN 2001; CDP 2008). The Millennium Development Goals, targeting achievement by 2015 (UN 2000) and the SDGs, targeting achievement by 2030 (UN 2015a), are recent global movements endorsed by the international community, with countries agreeing to collaborate for lifting LDCs out of poverty, illiteracy and epidemics (Fernández-Portillo et al. 2020). As a continuation of this effort, the UN Secretary-General established a COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund in 2020 “to respond to the pandemic and its impacts, including an unprecedented socioeconomic shock” (UN 2020b, p. 2). However, the international community and LDC governments have continuously relied on the private sector, multinational corporations and financial institutions (Pleines 2021) for financial support. This trend has increased the role of the market while LDC governments have remained unaccountable for the enduring crises of their public health and education sectors.

In a neoliberal political economy (Rizvi and Lingard 2010; Kissinger 2014), market fundamentalism is seen as key for the success of international collaboration, whereas strong democratic governments, which should be responsible for reducing inequality, are seen as a threat to the freedom of the market (Hayek 1944). Because of the decreasing trend of ODA from donor countries (UNCTAD 2020a; OECD 2021), as well as cuts in domestic funding for public health and education, private lenders and creditors are encouraged to invest in LDCs (UN 2020a). This trend has not only increased financialisation and cashflows in LDCs, but also their debt. Corrupt political leaders, some top-level bureaucrats and elite groups have benefited from this, while the people living in remote villages have suffered from diseases, famine, poverty and illiteracy (UN 2020a).

By comparison, the history of developed countries such as the US shows that a strong democratic government helped them to create institutional bases for an egalitarian social, economic and democratic system before the market was allowed to operate freely (Rodrik 2011; Piketty 2020). The US achieved substantial economic growth between the 1870s and 1890s because of the policy – implemented by its first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton – of having a strong central government. After World War II, the US implemented a European Recovery Programme (ERP) also known as the “Marshall Plan” (named after then Secretary of State George C. Marshall). It established bilateralism as an international development norm for addressing the challenges faced by developing countries. Furthermore, in the context of the dwindling colonial powers – mainly Britain, France, Germany and Japan –, the US took on a leadership role in establishing multilateral institutions such as the UN, the Bretton Woods Institutions and the OECD (Steil 2013). It is disappointing to note that none of these countries and their bilateral organisations have policies to create strong democratic governments in LDCs.

Despite very low capacity for spending the available budget, LDC governments have used the pandemic as a cause for seeking more loans from international donors (OECD 2021). Since public health and education are low in policy priority, the loans they have obtained are hardly invested in these sectors; instead they are used for buying manufactured goods, which reduces domestic production. For example, in 2020 alone, the Government of Nepal requested NRS 3.48 billion (about USD 29 million)Footnote 10 from the World Bank, NRS 13.09 billion (about USD 109 million) from the IMF, and NRS 7 billion (about USD 58.3 million) from the Asian Development Bank (MoF Nepal 2020). While loan amounts have continuously increased over the years, income from grants has fallen (Evans and Pablos-Méndez 2020). For example, the loans amount increased between the fiscal year 2015/2016 and 2019/2020 from 59.5% of total foreign aid to 85.2%, whereas the grants amount dropped from 40.5% to 14.8% (MoF Nepal 2020). For the sustainability of their economy, LDCs need to increase capital expenditure and seek grants, which not only reduces national debt, internal corruption and reliance on external donors, but also gives more autonomy to national governments to invest in public health and education (UNDP 2011).

In 2018, the total public debt of LDCs was 51% of their GDP (World Bank 2020). In 2020, the World Bank and the IMF announced that they would defer debt payment for a year and make LDCs eligible for borrowing additional loans as a pandemic response measure (ibid.). However, this announcement came with some conditionalities such as the requirement of using their own procurement procedure and compliance with IMF’s debt limit policy and the World Bank’s policy on non-concessional borrowing (World Bank 2020).

The amount of ODA commitment to LDCs, which many donor countries have never met, has not been revised (OECD 2021). Rather, some countries that used to meet minimum contribution levels have reduced ODAs in their post-pandemic fiscal budgets. For example, in November 2020, the UK government announced that it would reduce the UK’s ODA contribution from 0.7% to 0.5% of its GNI (Worley 2020). Similarly, Australia reduced its foreign aid by AUD 144 million in its 2021 federal budget (CoA 2021). Because of the debt crises, the dominance of market fundamentalism over democratic governance, and economic recession in the donor countries, the hope of the timely achievement of the SDGs has become utterly uncertain for LDCs.

However, on a positive note, the COVID-19 pandemic is also an opportunity for global solidarity for creating an equal and just world where everyone has a right to live a healthy, happy and prosperous life. As noted by the Centre for Development Policy, for “reaching the furthest behind first” (CDP 2021a, p. 8), the people living in remote LDC communities should be accorded priority not only in the distribution of vaccines but also in ensuring access to basic healthcare and education. Rather than relying on market fundamentalism, this is also a time to institutionalise democracy, create corruption control mechanisms, and make LDC governments accountable for the well-being of every citizen.

Notes

This article was originally drafted in October 2021. The evolution of a pandemic is particularly difficult to keep up with, and the effects of the current one, which is not over yet, are only beginning to emerge. While I have tried to update some of the statistics, the main message of this article has only become even more urgent over the past year.

The human assets index (HAI) is composed of six indicators grouped into two subindices for health and education (as shown in Figure 1). The per capita gross national income (GNI) reflects the income status and the overall level of resources available to a country. The economic and environmental vulnerability index (EVI) is composed of eight indicators, grouped into two subindices for economic and environmental vulnerabilities (UN 2022). Efforts to improve on these indicators are geared towards graduating from LDC status to “developing country” status.

Though education systems vary, in international literature, “grade 3” generally refers to students in their third year of primary school. Kaffenberger notes: “The choice of grade 3 is illustrative, as some learning has already occurred, but enough years remain to model long-term learning loss. The shock could be modelled for children in any grade” (Kaffenberger 2021, p. 2).

The creation of this was not realised until the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 (BWP 2019).

In a nutshell, Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek’s economic theory posits that the freedom of individuals for doing business and making profit will be curtailed if the market is controlled by a strong government.

Structural adjustment programmes are loans granted to economically weak countries “with strings attached”, i.e., they are linked to the fulfilment of certain conditions.

In 2020, Nepal had 125 government-owned hospitals (MoF Nepal 2020, p. 136). The number of private hospitals is increasing. An estimate shows that there are 366 private hospitals in Nepal (Adhikari 2013). In the school year 2020/2021, formal education was provided by 28,941 “community” (government or public) and 6,733 “institutional” (private or boarding) schools (MoE Nepal 2021, p. 33).

More than a year later, on 1 August 2022, Nepal (11,968 cumulative confirmed COVID-19-related deaths) has meanwhile been overtaken by Myanmar (19,434), while Bangladesh (29,292) still tops the Asian LDC death toll (Our World in Data 2022).

In Nepal, children enter school at age five, and formal schooling is compulsory and free of charge at primary level (lower basic: grades 1–5; upper basic: grades 6–8). Secondary level (lower secondary: grades 9–10; upper secondary: grades 11–12) is also free of charge, but not compulsory.

The exchange rate in 2020 was about USD 1 NRS 120.

References

Adhikari, S. (2013). Health is wealth: The rise of private hospitals in Nepal. New Business Age, 15 September [online article]. Retrieved 15 August 2022 from https://www.newbusinessage.com/MagazineArticles/view/490

Bastola, A., Ranjit, S., Rodriguez-Morales, A. J., Kumar Lal, B., Jha, R., Ojha, H. C., Shrestha, B., Chu, D. K. W., Poon, L. L. M., Costello, A., Morita, K., & Pandey, B. D. (2020). The first 2019 novel coronavirus case in Nepal. The Lancet, 20(3), 279–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30067-0

BBC News (British Broadcasting Corporation). (2021). Covid: Rich states “block” vaccine plans for developing nations [webnews item, 20 March]. London: BBC. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-56465395

Bhattacharya, D., & Islam, F. R. (2020). The COVID-19 scourge: How affected are the least developed countries? Development matters, 16 April [blog post]. Paris: OECD. Retrieved 21 Nov 2020 from https://oecd-development-matters.org/2020/04/23/the-covid-19-scourge-how-affected-are-the-least-developed-countries/

Boughton, J. M. (2002). Why White, not Keynes? Inventing the postwar international monetary system. IMF Working Paper SP/02/52. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 4 August 2022 from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2002/wp0252.pdf

BWP (Bretton Woods Project). (2019). What are the Bretton Woods Institutions? [dedicated webpage, 1 January]. London: BWP. Retrieved 4 August 2022 from https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2019/01/art-320747/#:~:text=The%20Bretton%20Woods%20Institutions%20are,to%20promote%20international%20economic%20cooperation

CBC News (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation). (2021). World Bank president on global vaccine equity, COVID-19 recovery [video clip of 9 June news broadcast, YouTube]. Toronto, ON: CBC News. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mE7wjCzI6xI

CDP (Committee for Development Policy). (2008). Handbook on the Least Developed Country category: Inclusion, graduation and special support measures (1st edn). New York: UN. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://tinyurl.com/38jdtkpw

CDP. (2018). Handbook on the Least Developed Country category: Inclusion, graduation and special support measures (3rd edn). New York: UN. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://tinyurl.com/38jdtkpw

CDP. (2021a). Committee for Development Policy: Report on the twenty-third session (22–26 February 2021a). New York: UN. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from http://undocs.org/en/E/2021a/33

CDP. (2021b). Handbook on the Least Developed Country category: Inclusion, graduation and special support measures (4th edn). New York: UN. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/LDC-Handbook-2021b.pdf

CDP. (2021c). List of Least Developed Countries (as of 24 November 2021c). New York: UN. Retrieved 1August 2022 from https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/ldc_list.pdf

Chowdhury, A. Z., & Jomo, K. S. (2020). Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries: Lessons from selected countries of the global South. Development, 63(2–4), 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-020-00256-y

CoA (Commonwealth of Australia). (2021). Budget strategy and outlook 2021–22: Budget Paper No. 1. Sydney, NSW: Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://budget.gov.au/2021-22/content/bp1/download/bp1_2021-22.pdf

De Herdt, T., & Titeca, K. (2016). Governance with empty pockets: The education sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Development and Change, 47(3), 472–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12235

Devkota, K. R. (2021). Inequalities reinforced through online and distance education in the age of COVID-19: The case of higher education in Nepal. International Review of Education, 67(1–2), 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-021-09886-x

Evans, T., & Pablos-Méndez, A. (2020). Negotiating universal health coverage into the global health mainstream: The promise and perils of multilateral consensus. Global Social Policy, 20(2), 220–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018120920245

Fernández-Portillo, L. A., Sianes, A., & Santos-Carrillo, F. (2020). How will COVID-19 impact on the governance of global health in the 2030 Agenda framework? The opinion of experts. Healthcare, 8(4), Art. no. 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040356

Friedman, M. (1955). The role of government in education. In R. A. Solo (Ed.), Economics and the public interest (pp. 123–144). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://tinyurl.com/2p8z3hns

Gale, T. (2001). Critical policy sociology: Historiography, archaeology and genealogy as methods of policy analysis. Journal of Education Policy, 16(5), 379–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930110071002

Gautam, D. K., & Gautam, P. K. (2021). Transition to online higher education during COVID-19 pandemic: Turmoil and way forward to developing country of South Asia – Nepal. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 14(1), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-10-2020-0051

Gleckman, H. (2018). Multistakeholder governance and democracy: A global challenge. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315144740

GoN (Government of Nepal). (1971). National education system plan 1971–1976. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal. Retrieved 14 August 2022 from https://www.martinchautari.org.np/storage/files/thenationaleducationsystemplanfor-1971-english.pdf

GoN. (1991). National health policy 1991. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from http://mohp.gov.np/downloads/National%20Health%20Policy-1991.pdf

GoN. (1992). Report of the National Education Commission 1992. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal. Retrieved 21 June 2021 from https://www.moe.gov.np/assets/uploads/files/2049_English.pdf

GoN. (1997). Second long-term health plan 1997–2017. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://dohs.gov.np/plan-policies/

GoN. (2014). National health policy 2014. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BxYPsAJu5Bn_dm5FZHh6ZthzSlU/view

GoN. (2016). School sector development plan 2016-2023. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal. Retrieved 21 June 2021 from http://www.moe.gov.np/article/772/ssdpfinaljuly-5-2017.html

Hayek, F. A. (1944). The road to serfdom. London: Routledge.

ILO (International Labour Organization). (2020). COVID-19: Tackling the jobs crisis in the least developed countries. Geneva: ILO. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://tinyurl.com/4rcwz2n7

IMF (International Monetary Fund). (2020). Nepal: Request for disbursement under the rapid credit facility. IMF Country Report No. 20/155, May. Washington, DC: IMF. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://tinyurl.com/yjdyd48p

Kaffenberger, M. (2021). Modelling the long-run learning impact of the Covid-19 learning shock: Actions to (more than) mitigate loss. International Journal of Educational Development, 81, Art. no. 102326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102326

Kissinger, H. (2014). World order: Reflections on the character of nations and the course of history. Penguin Press.

Kozul-Wright, R. (2020). Recovering better from COVID-19 will need a rethink of multilateralism. Development, 63(2–4), 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-020-00264-y

Lopes, H., & McKay, V. (2020). Adult learning and education as a tool to contain pandemics: The COVID-19 experience. International Review of Education, 66(4), 575–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-020-09843-0

Martin, E. M. (1972). The problems of the least developed countries. OECD Observer, 61, 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1787/observer-v1972-6-en

McMichael, P. (2012). Development and social change: A global perspective (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Meyer, H.-D. (2014). The OECD as pivot of the emerging global educational accountability regime: How accountable are the accountants? Teachers College Record, 116(9), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811411600907

Meyer, H.-D., Tröhler, D., Labaree, D. F., & Hutt, E. L. (2014). Accountability: Antecedents, power, and processes. Teachers College Record, 116(9), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811411600902

MoE Nepal (Ministry of Education). (2021). Flash I Report 2077 (2020–2021). Kathmandu: Ministry of Education. Retrieved 8 August 2022 from https://cehrd.gov.np/file_data/mediacenter_files/media_file-17-1312592262.pdf

MoF Nepal (Ministry of Finance). (2020). Nepal: Economic Survey 2019/2020. Kathmandu: Ministry of Finance. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://tinyurl.com/yc3xp7ah

Mundy, K. (2006). Education for all and the new development compact. International Review of Education, 52(1–2), 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-005-5610-6

Neupane, P., Bhandari, D., Tsubokura, M., Shimazu, Y., Zhao, T., & Kono, K. (2021). The Nepalese health care system and challenges during COVID-19. Journal of Global Health, 11, Art. no. 3030. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.11.03030

NPC Nepal (National Planning Commission). (2015). Nepal earthquake 2015: Post-disaster needs assessment. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://tinyurl.com/3mxd4swj

Nyerere, J. (1968). Education for self-reliance. Cross Currents, 18(4), 415–434.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). (2020). Intensive care beds capacity [online factsheet; status 20 April]. Paris: OECD. Retrieved 8 August 2022 from https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/data-insights/intensive-care-beds-capacity

OECD. (2021). COVID-19 spending helped to lift foreign aid to an all-time high in 2020 but more effort needed [webnews item, 13 April]. Paris: OECD. Retrieved 15 May 2021 from https://tinyurl.com/kkbjy3v2

Our World in Data. (2021). Daily new confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million people [online database; status 20 June]. Oxford: Our World in Data. Retrieved 20 June 2021 from https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/coronavirus-data-explorer

Our World in Data. (2022). Daily new confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million people [online database; status 1 August]. Oxford: Our World in Data. Retrieved 1 August 2022 from https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/coronavirus-data-explorer

Piketty, T. (2020). Capital and ideology. Transl. A. Goldhammer. Cambridge, MA/London: Belknap Press.

Pleines, H. (2021). The framing of IMF and World Bank in political reform debates: The role of political orientation and policy fields in the cases of Russia and Ukraine. Global Social Policy, 21(1), 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018120929773

Polanyi, K. (2001 [1944]). The great transformation: The political and economic origins of our time. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Regmi, K. D. (2015). The influence of supranational organizations on educational programme planning in the Least Developed Countries: The case of Nepal. Prospects, 45(4), 501–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-015-9352-3

Regmi, K. D. (2021). Educational governance in Nepal: Weak government, donor partnership and standardised assessment. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 51(1), 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2019.1587704

Rizvi, F., & Lingard, B. (2010). Globalizing education policy. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203867396

Rodrik, D. (2011). The globalization paradox: Why global markets, states, and democracy can’t coexist. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rubenson, K., & Desjardins, R. (2009). The impact of welfare state regimes on barriers to participation in adult education: A bounded agency model. Adult Education Quarterly, 59(3), 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713609331548

Savage, G. C., Gerrard, J., Gale, T., & Molla, T. (2021). The politics of critical policy sociology: Mobilities, moorings and elite networks. Critical Studies in Education, 62(3), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2021.1878467

Seetal, I., Gunness, S., & Teeroovengadum, V. (2021). Educational disruptions during the COVID-19 crisis in Small Island Developing States: Preparedness and efficacy of academics for online teaching. International Review of Education, 67(1–2), 185–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-021-09902-0

Shultz, L., & Viczko, M. (2021). What are we saving? Tracing governing knowledge and truth discourse in global COVID-19 policy responses. International Review of Education, 67(1–2), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-021-09893-y

Smyth, D. S. (2020). COVID-19, Ebola, and measles: Achieving sustainability in the era of emerging and reemerging infectious diseases. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 62(6), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2020.1820295

Stanistreet, P., Elfert, M., & Atchoarena, D. (2020). Education in the age of COVID-19: Understanding the consequences. International Review of Education, 66(5–6), 627–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-020-09880-9

Stanistreet, P., Elfert, M., & Atchoarena, D. (2021). Education in the age of COVID-19: Implications for the future. International Review of Education, 67(1–2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-021-09904-y

Steil, B. (2013). The battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the making of a new world order. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2003). Democratizing the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank: Governance and accountability. Governance, 16(1), 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0491.00207

UN (United Nations). (2000). United Nations Millennium Declaration: Resolution adopted by the General Assembly. A/RES/55/2. New York: UN. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://undocs.org/A/RES/55/2

UN. (2001). Programme of action for the least developed countries 2001–2010. Adopted by the Third United Nations Conference on the least developed countries in Brussels on 20 May. A/CONF.191/11. New York: UN. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from http://unctad.org/en/Docs/aconf191d11.en.pdf

UN. (2015a). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. UN General Assembly. A/70/L.1. New York: UN. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/70/L.1&Lang=E

UN. (2015b). Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development. Endorsed by the General Assembly in its resolution 69/313 of 27 July. New York: UN. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://tinyurl.com/3rmwnj3j

UN. (2019). Universal health coverage: Moving together to build a healthier world. Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage. New York: United Nations. Retrieved 8 August 2022 from https://www.un.org/pga/73/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2019/07/FINAL-draft-UHC-Political-Declaration.pdf

UN. (2020a). Implementation of the Programme of action for the least developed countries for the decade 2011–2020a. A/75/72–E/2020a/14. New York: UN. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://www.un.org/ldcportal/content/implementation-programme-action-least-developed-countries-decade-2011-2020a

UN. (2020b). The Secretary-General’s UN COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund. New York: UN. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://unsdg.un.org/resources/secretary-generals-un-covid-19-response-and-recovery-fund

UN. (2022). LDC identification criteria & indicators [dedicated webpage]. New York: United Nations. Retrieved 4 August 2022 from https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/least-developed-country-category/ldc-criteria.html

UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). (2020a). The least developed countries report 2020a: Productive capacities for the new decade. New York: United Nations. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://tinyurl.com/2p95fusk

UNCTAD. (2020b). Coronavirus: Let’s not forget the world’s poorest countries [webnews item, 27 April]. Geneva: UNCTAD. Retrieved 21 November 2020b from https://tinyurl.com/yckp83jj

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). (2011). Illicit financial flows from the least developed countries: 1990–2008. New York: UNDP. Retrieved 27 July 2022 from https://gfintegrity.org/report/report-least-developed-countries/

UNDP. (2019). Beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today: Inequalities in human development in the 21st century. Human Development Report 2019. New York: United Nations. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2019

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). (2011). Capacity development for Education for All: Translating theory into practice; the CapEFA Programme. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000212262

UN-OHRLLS (United Nations Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States). (2020). World’s most vulnerable countries lack the capacity to respond to a global pandemic [webnews item, 24 August]. New York: United Nations. Retrieved 26 July 2022 from https://www.un.org/ohrlls/news/world%E2%80%99s-most-vulnerable-countries-lack-capacity-respond-global-pandemic-credit-mfdelyas-alwazir

Valensisi, G. (2020). COVID-19 and global poverty: Are LDCs being left behind? The European Journal of Development Research, 32(5), 1535–1557. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00314-8

WEF (World Education Forum). (2000). The Dakar framework for action. Education for all: Meeting our collective commitments. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved 8 August 2022 from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001211/121147e.pdf.

WEF. (2016). Incheon declaration and Framework for action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4. Towards inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all. Education 2030. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved 8 August 2022 from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002456/245656e.pdf.