Abstract

This paper presents and tests a hypothesis that expands existing explanations of value creation in merger and acquisition (M&A) transactions. The main premise is that value creation is determined by not only the target’s pre-acquisition value, as indicated by numerous studies in extant literature, but also by the acquirer’s competency (among other factors) demonstrated by their pre-merger financial ratios. The paper shows that M&A transactions create value in the longer-run and the gain is commensurate with the acquirer’s historical performance and the target’s pre-acquisition value. Further, the paper employs statistical procedures and model-building techniques in order to develop and validate parsimonious Altman-style predictive models. The models reasonably identify successful M&A deals and are statistically significant and consistent with a few existing theories. Specifically, the evidence on liquidity supports internal capital markets hypothesis but does not support the theories of agency problems, while the evidence on financial leverage supports the view that lower debt enhances corporate control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Villalonga (2004a, b) documents a diversification premium and shows that diversification discount reported in earlier research is an artifact of sample construction. Others suggest that documented discount is a result of diversifiers’ tendency to acquire business units that are already selling at a discount (Graham et al. 2002; Campa and Kedia 2002).

Hund et al. (2010) use Pastor and Veronesi’s (2003) rational learning model to show that the initial adverse effect of M&A deals is mitigated over time as the segments “learn” to work together. Alhenawi and Krishnaswami (2015) show that M&A transactions erode value initially (consistent with value erosion story) but create value within a 5-year post-acquisition window (consistent with value creation story). They argue that previous work did not take into account the fact that it takes time for firms to realize and fully internalize the synergies of a merger. This is consistent with the view of Barraclough et al. (2013), who used call option prices to analyze market reaction to acquisition announcements and found that market prices tend to underestimate true synergy gains.

Other firm-specific and deal-specific factors as well as the pre-acquisition market value of the target are also included in the analyses.

This is an ex-post analysis but the developed Altman-style models are theoretically sound and statistically verified, which suggests that these models are likely to hold in an ex-ante analysis.

A study by Stevens (1973) uses ratio data and MDA to develop a model that discriminates the acquired group from the non-acquired group. Our work is significantly different in purpose and scope.

In addition, the interpretation of a single ratio is often non-informative unless it is buttressed with simultaneous analysis of other metrics and/or ratios. For instance, a high inventory turnover ratio relative to industry average might indicate highly effective inventory management, which leads to lower cost and higher profitability. However, high inventory turnover could possibly indicate that the firm does not carry adequate inventory, which normally hurts revenues and profitability. In order to discern between the two interpretations, one should look at profitability and cash flow ratios.

Before 1997, firms were required to report their segments as major lines of businesses. After 1997, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) No. 131 requires that segments are defined as the enterprise operating segments, which results in significant changes in reporting procedures (see Rajan et al. 2000). Categorizing segments this way is more representative because it makes divisions of diversified firms closer to pure-play firms used in estimating excess values.

Sample size in this paper is comparable to that of similar studies such as Ravichandran et al. (2009) who use 403 observations over 6 years; Freund et al. (2007) use 194 acquisitions from 1985 to 1998; Hyland (2003) uses 118 events during the period 1981–1992; Devos et al. (2009) investigates 264 acquisitions. Alhenawi and Krishnaswami (2015) use 316 merger events completed between 1998 and 2007 by 295 acquiring firms. The sample period ends in 2010 in order to allow for analysis of 3 years of post-acquisition performance.

Another methodological approach involves investigating market reaction to merger events by regressing returns on a measure of diversification, such as Herfindahl Index (as in Comment and Jarrell 1995) or by running an abnormal return analysis around divestiture dates (as in Berkovitch and Narayanan 1993; Desai and Jain 1999).

Mathematically, if the probabilities of false allocation of TQ, EVTA, and EVSL are α, β, and γ, respectively, then the probability of false allocation with Z1 and Z2 is \(e_{Z} = \alpha \times \beta \times \gamma .\) Since \(\alpha ,\;\beta\), and \(\gamma\) are less than one, \(e_{Z}\) is also less than one, and it is much smaller than \(\alpha ,\;\beta\), and \(\gamma\). Since the purpose of this study is to develop a predictive model, it is desirable to employ a strict classification. A similar approach is found in Jandik and Lallemand (2014) who classify a target firm as “high performer” if its “operating cash flow to market value of equity” ratio is greater than 1/3 of other firms, and its “average revenue growth” is also greater than 1/3 of other firms in the sample.

EPS is not discussed because it is a function of number of shares.

We compute excess value of the target based on total assets and based on sales. The results in Table 6 were obtained with total assets multiplier. The results with sales multiplier are similar but statistically weaker.

The table presents a few scattered observations that do not line up perfectly with previous findings. For instance, in the regressions of Z1 on \(R_{m,4} ,\) PT is statistically significant in the full model and is also present in the reduced model with a negative marginal effect indicating that the probability of success in M&A is reduced when the acquirer exhibit a higher payable turnover ratio. However, PT shows only in the Z1-\(R_{m,4}\) model. This observation and the rest of the scattered observations are ignored because they do not show in all models (Wooldridge 2009).

We have also conducted year and industry fixed effect analyses (results are not shown). We found no industry effect and inconsistent year effect (negative in 1998, 2005 and 2006, positive in 2000 and 2008, insignificant in other years). Given that performance is measured within a 3-year post-event window, M&A completed in 1998, 2005, and 2006 might exhibit lower performance because of market downturns in 2000 and 2008. Similarly, positive year effect in 2000 and 2008 might be an artifact of market recovery (see Dimitrov and Tice 2006). Nonetheless, the overall validity of other findings is not sensitive to year and industry effects.

Payment method (PMT) is not selected by the reduced stepwise logistic regressions, but it was selected by the stepwise regressions with continuous measures TQ, EVTA, EVSL. In a non-tabulated test, we found that the difference between average abnormal return of a portfolio of M&As paid with stock (PMT = 1) and average abnormal return of a portfolio of M&As paid with cash (PMT = 0) is statistically significant. The same argument applies to TGTEX. In fact, we re-examined all variables to formulate the model in E8.

TGTEX is the excess value of the target based on total assets multiplier. Previous tests in this paper have shown that TGTEX computed based on asset multiplier generates statistically more significant results than TGTEX with sales multiplier.

Specifically, since the structure matrix is unaffected by collinearity and since the ordering in structure matrix is not fundamentally different from the ordering of standard canonical coefficients, it's safe to say that collinearity has not inflated the importance of predictors in the standard coefficients table.

The coefficients in Panel B may not be readily comparable because the measurement units of the ratios are not homogenous.

Consistent with extant literature, the success of an M&A event is significantly associated with certain attributes of the deal, such as access to capital, size, and payment method. Access to capital prior to the merger event increases the likelihood of observing a successful M&A (as in Servaes 1996). The positive coefficient on SIZE variable in Z1 and Z2 models indicates that more successful M&As are made by larger acquirers, but the negative sign in Z3 and Z4 models does not support that view. M&As are more likely to be successful when the deal is paid out for by cash, which is consistent with the findings of Moeller et al. (2004). In our sample, public status of the target (investigated by Chang 1998; Fuller et al. 2002) and ratio of target equity to the acquirer’s equity (investigated by Asquith et al. 1983) are not determinants of M&A success.

The CAR [−1, +1] and CAR [−2, +2] results are generally comparable and are available upon request from the authors.

Bettis and Mahajan (1985) investigate the risk-return tradeoff in profits for 80 related and unrelated events and find that related ones outperform the unrelated. Wernerfelt and Montgomery (1988) use Tobin’s Q as a measure of performance and find that narrowly diversified firms do better than widely diversified ones. Berger and Ofek (1995) compare the sum of imputed stand-alone values to the firm's actual value and find that value loss is smaller when the segments of the diversified firm are in the same two-digit SIC code. Nevertheless, our finding does not support the organizational competencies hypothesis of Matsusaka (2001), where firms diversify when sales decline in their own industry. Instead of going out of business, they step into a new industry that “matches” their competencies and, therefore, successful diversifiers quit their original industry and transition into the new industry.

Empirically, Maloney et al. (1993) shows that the acquirer’s leverage position is positively related to the deal announcement return. They also show that stock price performance of the acquiring firm is positively influenced by leverage-increasing restructuring. The signs of the leverage ratio in our models point in the other direction.

Following Berger and Ofek (1995), we also calculate excess value based on EBIT multiplier. We obtained a much smaller sample due to lack of data and elimination of negative segment imputed value.

We show mathematical notation using total assets (TA) multiplier only. Imputed value with sales (SL) multiplier is computed in an analogous manner.

In robustness testing, we calculate cumulative abnormal return using the 2-year (+30, +720) and 1-year (+30, +360) post-event window. In the former case, the findings (not tabulated) became slightly weaker but the key implications are not significantly affected. With 1 year horizon, statistical significance of the findings is largely compromised.

In a robustness check, we used the value of TQ, EVTA, and EVSL at the end of the third year. Results are not fundamentally different but are statistically weaker.

We also computed \(R_{m,16}\) as,

$$R_{m,16}=\left(\sum_{Q=-20}^{Q=-5} R_{m,Q}\right){/}16$$Results are not fundamentally different from those obtained with \(R_{m,20}.\)

If the board of directors and institutional shareholders of the acquiring firm question the deal, managers might attempt to assuage pressure by delivering strong performance, creating incentives for misreporting.

They surveyed CFOs about the primary motives behind corporate M&A strategies and found that “synergy” (in the form of operating economies of scope and scale, financial economies, and increased market power) and “diversity” seem to be top motives.

Information regarding payment type, target public status, and nature of the deal were collected from 8-Ks or 10-Ks in SEC electronic files or Lexis and Nexis.

References

Aggarwal RK, Samwick AA (2003) Performance incentives within firms: the effect of managerial responsibility. J Financ 58(4):1613–1650

Alhenawi Y, Krishnaswami S (2015) Long-term impact of merger synergies on performance and value. Q Rev Econ Finance. doi:10.1016/j.qref.2015.01.006

Altman E (1968) Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. J Finance 23:589–609

Altman E (1984) A further empirical investigation of the bankruptcy cost question. J Finance 39:1067–1089

Andrade G, Mitchell M, Stafford E (2001) New evidence and perspectives on mergers. J Econ Perspect 15:103–120

Andreou P, Louca C, Savva C (2016) Short-horizon event study estimation with a STAR model and real contaminated events. Rev Quant Finance Account 47(3):673–697. doi:10.1007/s11156-015-0515-3

Asquith P, Bruner R, Mullins D (1983) The gains to bidding firms from merger. J Financ Econ 11(1–4):121–139

Barraclough K, Robinson DT, Smith T, Whaley RE (2013) Using option prices to infer overpayments and synergies in M&A transactions. Rev Financ Stud 26(3):695–722

Baxamusa M, Javaid S, Harery K (2015) Network centrality and mergers. Rev Quant Finance Account 44:393–423

Beaver W (1966) Financial ratios as predictors of failure. J Account Res 4:71–111

Berger PG, Ofek E (1995) Diversification’s effect on firm value. J Financ Econ 37(1):39–65

Berger PG, Ofek E (1996) Bustup takeovers of value-destroying diversified firms. J Financ 51(4):1175–1200

Berkovitch E, Narayanan MP (1993) Motives for takeovers: an empirical investigation. J Financ Quan Anal 3:347–362

Bettis RA, Mahajan V (1985) Risk/return performance of diversified firms. Manag Sci 31(7):785–799

Bouwman CHS, Fuller K, Nain AS (2009) Market valuation and acquisition quality: empirical evidence. Rev Financ Stud 22(2):633–679

Branch B, Yang TW (2006) The risk arbitrage performance: failed acquisition attempts. Q J Bus Econ 45:53–68

Campa JM, Kedia S (2002) Explaining the diversification discount. J Finance 57:1731–1762

Chang S (1998) Takeovers of privately held targets, method of payment, and bidder returns. J Finance 53(2):773–784

Chen C, Steiner T (2000) An agency analysis of firm diversification: the consequences of discretionary cash and managerial risk considerations. Rev Quant Finance Account 14:247–260

Comment R, Jarrell GA (1995) Corporate focus and stock returns. J Financ Econ 37(1):67–87

CFA Institute (2012) CFA program curriculum. Volume 3: financial reporting and analysis. Level I. 7th edn. Pearson

Denis D, Denis D, Sarin A (1997) Agency problems, equity ownership and corporate diversification. J Finance 56:2299–2335

Desai H, Jain J (1999) Firm performance and focus: long-run stock market performance following spinoffs. J Financ Econ 54(1):75–101

Devos E, Kadapakkam P, Krishnamurthi S (2009) How do mergers create value? A comparison of taxes, market power, and efficiency improvements as explanations for synergies. Rev Financ Stud 22:1179–1211

Dimitrov V, Tice S (2006) Corporate diversification and credit constraints: real effects across the business cycle. Rev Financ Stud 19:1465–1498

Dong M, Hirshleifer D, Richardson S, Teoh S (2006) Does investor misvaluation drive the takeover market? J Finance 61(2):725–762

Ederington LH, Yawitz JB, Roberts BE (1987) The information content of bond ratios. J Financ Res 10(3):211–268

Evans RD (1991) Two experiments with stepwise regression. J Econ Finance 15(2):35–42

Fezzari SM, Hubbard GR, Peterson BG (1988) Financing constraints and corporate investment. Brook Pap Econ Act 1:141–195

Freund S, Trahan E, Vasudevan G (2007) Effects of global and industrial diversification on firm value and operating performance. Financ Manag 36:143–161

Fu F, Lin L, Officer MS (2013) Acquisitions driven by stock overvaluation: are they good deals? J Financ Econ 109(1):24–39. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.02.013

Fuller K, Netter J, Stegemoller M (2002) What do returns to acquiring firms tell us? Evidence from firms that make many acquisitions. J Finance 57(4):1763–1794

Gibbons R, Murphy KJ (1992) Optimal incentive contracts in the presence of career concerns: theory and evidence. J Polit Econ 100:468–505

Graham JR, Lemmon ML, Wolf JG (2002) Does corporate diversification destroy firm value? J Finance 57:695–720

Grossman S, Hart OD (1981) The allocational role of takeover bids in situations of asymmetric information. J Finance 36(2):253–270

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL (2006) Multivariate data analysis, 6th edn. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Harris M, Kriebel CH, Raviv A (1982) Asymmetric information, incentives and intrafirm resource allocation. Manag Sci 28:604–620

Harrison J, Hart M, Oler D (2014) Leverage and acquisition performance. Rev Quant Finance Account 43(3):571–603. doi:10.1007/s11156-013-0385-5

Huang-Meier W, Lambertides N, Steeley J (2016) Motives for corporate cash holdings: the CEO optimism effect. Rev Quant Finance Account 47(3):699–732. doi:10.1007/s11156-015-0517-1

Hund J, Monk D, Tice S (2010) Uncertainty about average profitability and the diversification discount. J Financ Econ 96(3):463–484

Hyland DC (2003) The effect of diversification on firm value: a pre- and post- diversification analysis. Stud Econ Finance 21(2):22–39

Hyland DC, Diltz DJ (2002) Why firms diversify: an empirical examination. Financ Manag 31(1):51–81

Ishii J, Xuan Y (2014) Acquirer-target social ties and merger outcomes. J Financ Econ 112:344–363

Jandik T, Lallemand J (2014) Value impact of debt issuances by targets of withdrawn takeovers. J Corp Financ 29:475–494

Jensen M (1986) Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance and takeovers. Am Econ Rev 76:323–329

Jensen M (2005) Agency costs of overvalued equity. Financ Manag 34:5–19

Jensen M, Meckling W (1976) Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3:305–360

Lamont O (1997) Cash flow and investment: evidence from internal capital markets. J Finance 52:83–109

Lang LHP, Stulz RM (1994) Tobin’s Q, corporate diversification, and firm performance. J Polit Econ 102(6):1248–1280

Lee S, Lim K (2006) The impact of M&A and joint ventures on the value of IT and non-IT firms. Rev Quant Finance Account 27(2):111–123

Lev B, Thiagarajan SR (1993) Fundamental information analysis. J of Account Res 31(2):190–215

Lewellen W (1971) A pure financial rationale for the conglomerate merger. J Finance 26:521–537

Maksimovic V, Philips G (2007) Conglomerate firms and internal capital markets. In: Espen Eckbo B (ed) Handbook of corporate finance, vol 1. North Holland, Amsterdam

Maloney MT, McCormick RE, Mitchell ML (1993) Managerial decision making and capital structure. J Bus 66(2):189–217

Marquardt DW (1970) Generalized inverses, ridge regression, biased linear estimation, and nonlinear estimation. Technometrics 12(3):591

Matsusaka JG (2001) Corporate diversification, value maximization and organizational capabilities. J Bus 74:409–431

Matsusaka JG, Nanda V (2002) Internal capital markets and corporate refocusing. J Financ Intermed 11(2):176–207

McWilliams A, Siegel D (1997) Event studies in management research: theoretical and empirical issues. Acad Manag J 40(3):626–657

Menard S (1995) Applied logistic regression analysis. Sage University paper series on quantitative applications in the social sciences, 07-106. Thousand Oaks

Moeller SB, Schlingemann FB, Stulz RM (2004) Firm size and the gains from acquisitions. J Financ Econ 73(2):201–228

Mukherjee TK, Kiymaz H, Baker KH (2004) Merger motives and target valuation: a survey of evidence from CFOs. J Appl Finance 14(2):7–24

Myers S, Majluf NS (1984) Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. J Financ Econ 13:187–221

Neter J, Wasserman W, Kutner MH (1989) Applied linear regression models. Irwin, Homewood

Ou JA, Penman SH (1989a) Accounting measurement, price-earnings ratio, and the information content of security prices. J Account Res 27(3):111–144

Ou JA, Penman SH (1989b) Financial statement analysis and the prediction of stock returns. J Account Econ 11(4):295–329

Pastor L, Veronesi P (2003) Stock valuation and learning about profitability. J Finance 58:1749–1789

Piotroski JD (2000) Value investing: the use of historical financial statement information to separate winners from losers. J Account Res 38(3):1–41

Rajan RG, Servaes H, Zingales L (2000) The cost of diversity: the diversification discount and inefficient investment. J Finance 55:35–80

Ravichandran T, Liu Y, Han S, Hasan I (2009) Diversification and firm performance: exploring the moderating effects of information technology spending. J Manag Inf Syst 25(4):205–240

Rotemberg JJ, Saloner G (1994) Benefits of narrow business strategies. Am Econ Rev 84(5):1330–1149

Rumelt RP (1974) Strategy, structure, and economic performance. Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University, Boston

Safieddine A, Titman A (1999) Leverage and corporate performance: evidence from unsuccessful takeovers. J Finance 2:547–580

Scholes M, Williams J (1977) Estimating betas from nonsynchronous data. J Financ Econ 5(3):309–327

Servaes H (1996) The value of diversification during the conglomerate merger wave. J Finance 51:1201–1226

Shin HH, Stulz RM (1998) Are internal capital markets efficient? Q J Econ 113(2):531–552

Shleifer A, Vishny R (1990a) Managerial entrenchment, the case of manager specific investments. J Financ Econ 25:123–139

Shleifer A, Vishny R (1990b) The takeover wave of the 1980s. Science 249:745–749

Stein J (1997) Internal capital markets and the competition for corporate resources. J Finance 52:111–133

Steiner TL (1996) A reexamination of the relationships between ownership structure, firm diversification, and Tobin’s Q. Q J Bus Econ 35(4):39–48

Stevens DL (1973) Financial characteristics of merges firms: a multivariate analysis. J Financ Quant Anal 8(2):149–158

Stulz RM (1990) Managerial discretion and optimal financing policies. J Financ Econ 26:3–27

Subramaniam VT, Tang H, Yue M, Zhou X (2011) Firm structure and corporate cash holdings. J Corp Finance 17(3):759–773

Villalonga B (2004a) Diversification discount or premium? New evidence from the business information tracking series. J Finance 59:475–502

Villalonga B (2004b) Does diversification cause the diversification discount? Finance Manag 33:5–27

Wernerfelt B, Montgomery CA (1988) Tobin’s Q and the importance of focus in firm performance. Am Econ Rev 78(1):246–250

Wooldridge JM (2009) Introductory econometrics: a modern approach, 4th edn. South-Western College Publishing, Cincinnati

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Tobin’s Q, excess value, and abnormal return

We use the following notation:

- N :

-

Number of diversifiers (parent company) in the sample of this paper

- i = 1, 2, …, N :

-

Subscript that identifies diversifier i in the sample

- M :

-

Number of segments in the parent (diversifier) company

- j = 1, 2, …, M :

-

Subscript that identifies segment j in the parent company

- K :

-

Number of competitors in the same market (firms with the same SIC code as the parent company)

- k = 1, 2, …, K :

-

Subscript that identifies competitor k in the market

- Q :

-

Number of matching pure-plays of a segment (firms with the same last two digits of SIC code as the segment)

- q = 1, 2, …, Q :

-

Subscript that identifies matching pure play q

1.1 Tobin’s Q (TQ)

Tobin’s Q is the ratio of market value of assets to the book value of assets. Tobin’s Q is a classical measure of performance used in diversification literature (see Lang and Stulz 1994; Servaes 1996; Steiner 1996; Dong et al. 2006) we calculate Tobin’s Q as,

\(MVE_{i}\), Market Value of Equity; \(BVL_{i}\), Book Value of Liabilities; \(BVE_{i}\), Book Value of Equity.

1.2 Excess value (EX)

We follow Berger and Ofek’s (1995) procedure in estimating the imputed value of each segment. First we calculate imputed value of each segment j in a diversifier i as median ratio of total capital to total assets (or salesFootnote 25) of matching pure-play firms multiplied by total assets (or sales) of segment j. Matching pure play firms are in the same SIC code of segment j, have at least $20 million in sales, and have sufficient data on Compustat. Mathematically,Footnote 26

\(IV_{j}^{i}\), Imputed value of segment j in firm i; \(TA_{j}^{i}\), Total assets of segment j in firm i (identifiable total assets in Compustat segments database); \(TC_{q}\), Total capital of a pure-play firm q in the same industry of segment j; \(MVE_{q}\), Market Value of Equity of a pure-play firm q in the same industry of segment j; \(BVL_{q}\), Book Value of Liabilities of a pure-play firm q in the same industry of segment j; \(TA_{q}\), Total Asset of a pure-play firm q in the same industry of segment j.

The sum of the imputed values of the M segments in firm i becomes the imputed value of the firm i (its value if all of its M segments were operated as stand-alone businesses):

Next, we measure the percentage difference between diversifier i’s total value and the sum of imputed values for its M segments as stand-alone entities. If market value (total capital) of firm i is \(TC_{i}\) then we calculate percentage difference (excess value) as:

\(TC_{i}\), Total capital of a firm i; \(MVE_{i}\), Market Value of Equity of firm i; \(BVL_{i}\), Book Value of Liabilities of a firm i.

1.3 Abnormal returns

Abnormal return is the difference between observed stock return and a hypothetical return for the scenario where the event did not happen. The hypothetical return is computed using the market model approach (three-factor model of Fama and French). The parameters of the model are estimated over the window (−720, −90) trading days preceding the deal announcement date. The exclusion of 90-day pre-event window minimizes the effect of possible leakage of information (Scholes and Williams 1977).

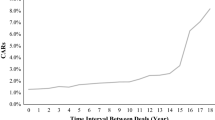

For each firm in the sample, we compute cumulative abnormal return (CAR), which reflects total valuation effect of the merger. CARs are calculated beginning 30 days after the event through 3 years after the event, that is, within an event window spanning (+30, +1080) trading days after the deal announcement date. The exclusion of the 30-day post-event windows eliminates the effect of possible adjustment to the share price following the announcement (Scholes and Williams 1977). The relatively long horizon surely raises several concerns (discussed below), but it allows the M&A effect to be fully impounded in stock prices. The work of Hund et al. (2010) and Alhenawi and Krishnaswami (2015) indicate that it takes time for the M&A advantages to materialize and, hence, short-run analysis does not capture the full effect of M&A events on value.Footnote 27

In computing cumulative abnormal return, we were conscious of the pitfalls of long-term event studies. For instance, consecutive acquisitions made by the same acquirers are treated as separate events and the data is clean of observation with confounding merger events near the studied window (McWilliams and Siegel 1997). Second, this study uses a sample of 454 observations; this mitigates the outlier and robustness-of-significance problems (McWilliams and Siegel 1997). Nevertheless, several other empirical concerns remain present in the analysis. For instance, we cannot ensure that other events are not driving the long-term abnormal returns. In addition, this test does not account for potential interaction between financial ratios and does not capture the relative strengths of pre-event conditions in predicting post-merger performance. These pitfalls are accounted for in regression analysis explained in subsequent sessions. Finally, long-term event studies suffer sizable type I and type II errors. We believe this issue is mitigated by the fact we use three other long-term measures of performance: Tobin’s Q, asset-based excess value, and sales-based excess value. Further, the predictive models use the dichotomous variables Z3 and Z4; not raw CAR. We believe this mitigates, at least partially, CAR problems (see Sect. 4.3 for more details).

Appendix 2: Post-acquisition performance measures

2.1 Using Tobin’s Q and excess value

Hund et al. (2010) show that the synergies of M&A deals materialize over time. Specifically, they show that an average M&A may initially erode value but exhibits sustained recovery afterward. In a similar vein, Barraclough et al. (2013) show that short-term price reaction to a M&A announcement tends to underestimate true synergies of the deal. Accordingly, we gauge post-acquisition performance over three post-acquisition years. For each transaction, we compute time-series averages of TQ, excess value based on total assets (EVTA), and excess value based on sales (EVSL) (one at a time) of the combined firm using data from years 0, 1, 2, and 3. That is,

where \(m = 1, 2, \ldots , 454\) indexes diversifiers and t indexes time distance (in years) from event. Thus, \(V_{m, t}\) is the measure of performance of diversifier m computed in the tth year and \(V_{m,Avg}\) is the time-series average of \(V_{m, t} .\) Footnote 28 For each of the three measures of post-acquisition performance (TQ, EVTA, and EVSL), we compute the difference \(\Delta Y = Y_{t = 3} - Y_{t = - 1}\) where \(t = - 1\) indicates the year ending immediately prior to the M&A completion and \(t = 3\) indicates 3 years after completion. For each measure, a positive \(\Delta Y\) indicates success and a negative \(\Delta Y\) indicates failure.

2.2 Dichotomous measures of M&A success

We create the first dichotomous variable Z1, where \(Z1 = 1\) when the M&A generates three positive differences (i.e., \(\Delta TQ > 0\) and \(\Delta EVTA > 0\) and \(\Delta EVSL > 0\)) and \(Z1 = 0\) with three negative differences (mixed combinations are eliminated from the sample). Then, we create the second dichotomous variable Z2, where \(Z2 = 1\) when the M&A generates three differences above the corresponding medians of differences (i.e., \(\Delta TQ > Median\,\Delta TQ\) and \(\Delta EVTA > Median\,\Delta EVTA\) and \(\Delta EVSL > Median\,\Delta EVSL\)) and \(Z2 = 0\) with three below-median differences (mixed combinations are eliminated from the sample). Variables Z1 and Z2 supply a conservative measure of M&A event success.

We create another two variables, Z3 and Z4, using abnormal returns. \(Z3 = 1\) if the M&A generates positive abnormal return; otherwise, \(Z3 = 0\). \(Z4 = 1\) if the M&A generates above-median abnormal return. If neither of these conditions is met, \(Z4 = 0\). While Z3 and Z4 are less conservative than Z1 and Z2, they do not require reduction in sample size.

Appendix 3: Measures of pre-acquisition performance and other control variables

3.1 Financial ratios

A list of 20 pre-acquisition financial ratios is computed for each acquirer. Financial ratios are sensitive to transitional activities. For instance, a non-ordinary transaction (e.g., sale of an asset) may artificially boost liquidity. In order to smooth out transitional effects, we compute two time-series averages (of each ratio) as follows,Footnote 29

where \(m = 1, 2, \ldots , 454\) indexes diversifiers and Q indexes time distance (in quarters) from event. Thus, \(R_{m, Q}\) is the financial ratio R of diversifier m in the Qth quarter and \(R_{m, 4}\) is the time-series average of \(R_{m, Q}\) that captures the acquirer’s performance immediately before the completion of the deal. Since \(R_{m, 4}\) might be subject to potential window dressing behavior (i.e., misreporting in the face of event-related pressureFootnote 30), we also use \(R_{m, 20} ,\) which is computed with 20 pre-acquisition quarters.

3.2 Relatedness and target’s pre-acquisition value

Several authors have shown that a target’s characteristics play a significant role in post-acquisition performance of the combined firm. For instance, Graham et al. (2002) and Campa and Kedia (2002) suggest that diversification discount can be explained by the diversifiers’ tendency to acquire already discounted business units. Following Graham et al. (2002), we compute the targets’ excess value immediately prior to the acquisition, that is, in their last year of operating as stand-alone firms (year −1). The findings are reported in Table 1 above. Pre-acquisition excess value of target firms (TGTEX) is included in subsequent analysis to control for the potential effect of target pre-acquisition performance.

We also control for relatedness (REL), which is almost a standard in M&A literature because related mergers tend to create increased post-acquisition synergies relative to unrelated mergers (see Bettis and Mahajan 1985; Wernerfelt and Montgomery 1988; Berger and Ofek 1995). A survey study by Mukherjee et al. (2004) confirms existence of operational and strategic advantages of diversification and indicates that managers anticpate higher synergies in related acquisitions.Footnote 31 Rumelt (1974) and Lewellen (1971) noted that operational advantages of a merger are more likely to materialize in intra-industry mergers (i.e., related events). Following Berger and Ofek (1995), an M&A transaction is considered “related” if the first two digits of the SIC code of the acquirer match the first two digits of the target. Thus, the dichotomous variable REL equals 1 for related acquisitions and 0 otherwise.

3.3 Other control variables

We control for size (SIZE) and access to capital market (ATC). We also control for transaction-specific characteristics, such as target’s public status (TGT), method of payment (PMT), and deal’s size relative to the acquirer’s market value (DEAL). Size is an important factor commonly used in M&A literature. For instance, Moeller et al. (2004) finds that M&A announcement returns are lower for acquisitions by larger firms. Lewellen (1971) pointed out that diversification strategy could be motivated by the desire to enhance access to capital markets. In effect, the measures of M&A performance might be upward biased because it reflects improvement in borrowing capacity. Thus, we include a dummy variable (ATC) to capture access to capital markets. ATC equals 1 if the firm pays a dividend and 0 otherwise.Footnote 32 Prior research has shown negative market reaction to M&A announcement when the target is a public company (e.g., Chang 1998; Fuller et al. 2002), when stock is used as a method of payment (Moeller et al. 2004), and when the ratio of target equity to the acquirer’s equity is smaller (Asquith et al. 1983).Footnote 33

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alhenawi, Y., Stilwell, M. Value creation and the probability of success in merger and acquisition transactions. Rev Quant Finan Acc 49, 1041–1085 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-017-0616-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-017-0616-2