Abstract

A framework for simplified implementation of the collective model of labor supply decisions is presented in the context of fiscal reforms in the UK. Through its collective form the model accounts for the well known problem of distribution between wallet and purse, a broadly debated issue which has so far been impossible to model due to the limitations of the unitary model of household behavior. A calibrated data set is used to model the effects of introducing two forms of the Working Families’ Tax Credit. We also summarize results of estimations and calibrations obtained using the same methodology on data from five other European countries. The results underline the importance of taking account of the intrahousehold decision process and suggest that who receives government transfers does matter from the point of view of labor supply and welfare of household members. They also highlight the need for more research into models of household behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Euro conversion rate: £1=€1.4524 (based on www.ft.com currency converter, of April 17th, 2003).

A non-refundable credit reduces tax liability only if such a liability arises, i.e. only if an individual has enough income to pay income tax. This is different from a refundable credit, which can be paid out in a form of negative tax even in cases where an individual has no taxable income.

In April 2003, the WFTC was replaced by a new system of financial support for low-income families with children. As part of the same package of reforms, the principle of in-work support for the low-paid has been extended to those without children in low-paid full-time employment. For details see Brewer (2003).

WFTC includes also a generous childcare credit equivalent to 70 per cent of childcare costs up to a rather generous maximum. This is available to single parents and couples conditional on both partners working at least 16 h a week. The maximum amount of childcare credit is 70 per cent of childcare costs up to £100 for people with one child and up to £150 for those with two or more children. Under FC, there was an income disregard of £60 per week on childcare expenditure. Take up of child-care related financial support has been low under both FC and WFTC and we do not include this part of the reform in our modeling. For details of how childcare support changed between Family Credit and WFTC see for example, Myck (2000).

The WFTC reform only affects households with children. Our sample therefore includes households with children, where we limit the number of those to two, in an attempt to limit the potential effects of labor supply constraints which are not directly related to financial gains to work.

We shall use interchangeably the terms “bargaining power” and “welfare weight”, in order simply to avoid tedious repetitions. But note that due to the nonconvexity of budget sets the welfare weight does not correspond to a linear combination of spouses’ utilities.

In this application of the Vermeulen et al. (2006) methodology we do not allow δ to be different for men and women, and we use calibrated rather than predicted values of δ.

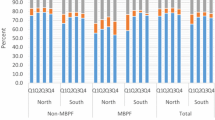

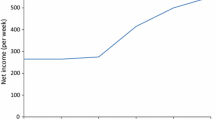

We split both the male and the female hours distributions into 7 h brackets: 0–5, 6–15, ..., 45–55, 56+, and calculate net incomes for these brackets respectively at: 0, 10, ... , 50 h and 60 h of work. The value is divided by 100 for numerical and presentational reasons.

The scaling is again guided by the reasons given in Footnote 11.

See Vermeulen et al. (2006) for some qualification of this statement.

See Section 6 for results obtained for other countries.

Note that the WFTC retains the conditionality of the transfer on a minimum number of hours worked (16 h per week worked by either member) as in its predecessor, the Family Credit.

Out of 2619 couples with children in our sample, the budget constraint is unchanged by the WFTC for 676 couples.

WFTC is restricted to those with savings less than £8000. Eligibility is reduced (by £1 for every £250 of savings) for those with savings above £3000.

It is difficult to think of an example of such a reform in the case where we define the distribution of unearned income relative to overall net family income. Any reform affecting net incomes would change the value of the variable summarizing this distribution even if absolute values of unearned incomes remained unaffected.

If we simulated the reform in a framework which would allow modeling the choice of labor supply with a continuous hours distribution we would expect a change in the labor supply of all couples who would see their Pareto frontier and/or bargaining power change as a result of the WFTC.

Note that the interpretation of aggregate changes in utility requires some caution as averaging across individuals and households implies cardinalization of utility. However, we use these average figures only to reflect differences between the three systems and we think that these reflect the implications of the two versions of WFTC.

As mentioned in Footnote 6 the WFTC reform included a more generous treatment of childcare expenses for working families. This part of the reform in not modeled here. Initially take-up of the childcare tax credit was very low, so excluding it from our analysis should not distort the results too strongly. However, with the signs of increases in the take-up of childcare related credits it seems that any future analysis of the effect of tax credits on labor supply should account for childcare expenses and the related subsidies.

For references see Vermeulen et al. (2006).

These changes were introduced by the previous government.

Note, however, that children in our model are not taken up in a structural way. A more structural model accounting for expenditure on children is presented in Blundell, Chiappori, and Meghir (2005).

References

Adam, S., & Kaplan, G. (2002). A survey of the UK tax system. IFS Briefing Note no. 9. http://www.ifs.org.uk/taxsystem/taxsurvey.pdf.

Blundell, R., & Walker, I. (1986). A life-cycle consistent empirical model of family labor supply using cross-section data. Review of Economic Studies, 53, 539–558.

Blundell, R., Chiappori, P-A., & Meghir, C. (2005). Collective Labor Supply with Children. Journal of Political Economy, 113, 1277–1306.

Blundell, R., Lechene, V., & Myck, M. (2002). Tax credit reforms and labour supply in a collective model. Mimeo. London: IFS.

Blundell R., Duncan A., McCrae J., & Meghir C. (2000). The labour market impact of the working families’ tax credit. Fiscal Studies, 21, 65–74.

Bourguignon, F., Browning, M., Chiappori, P-A., & Lechene, V. (1993). Intra household allocation and consumption: a model and some evidence from French data. Annales d’Économie et de Statistique, 29, 137–156.

Brewer, M. (2003). The new tax credits. IFS Briefing Note No. 35. London: IFS. http://www.ifs.org.uk/taxben/bn35.pdf.

Brewer, M., Clark, T., & Wakefield, M. (2002). Five Years of Social Security Reform in the UK.” IFS Working Paper no. 12/02. London: IFS.

Chiappori, P-A. (1992). Collective labor supply and welfare. Journal of Political Economy, 100, 437–467.

Department for Work and Pensions. (2001). “Income Related Benefits: Estimates of Take-up: 1998/99.” London: Department of Work and Pensions. http://www.dwp.gov.uk/.

Gregg, P., Johnson, P., & Reed, H. (1999). Entering work and the british tax and benefit system. London: IFS.

Inland Revenue (2002). Working Families’ Tax Credit – Quarterly Enquiry. London: Inland Revenue.

Kaplan, G., & Leicester, A. (2002). A Survey of the UK Benefit System. IFS Briefing Note no. 13. London: IFS.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. A. (1996). Bargaining and distribution in marriage. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10, 139–158.

Myck, M. (2000). Fiscal Reforms Since May 1997. IFS Briefing Note no. 14. London: IFS.

Van Soest, A. (1995). Structural models of family labor supply. A discrete choice approach. Journal of Human Resources, 30, 63–88.

Vermeulen, F., Bargain, O., Beninger, D., Beblo, M., Blundell, R., Chiuri, M-C., Carrasco, R., Laisney, F., Lechene, V., Moreau, N., Myck, M., & Ruiz-Castillo, J. (2006). Collective models of household labor supply with nonconvex budget sets and nonparticipation: a calibration approach. Review of Economics of the Household, 4, 113–127.

Acknowledgements

This paper exploits work done in the 1-year project “Welfare analysis of fiscal and social reforms in Europe: does the representation of the family decision process matter?”, partly financed by the EU, General Directorate Employment and Social Affairs, under grant VS/200/0778. We are grateful for comments and advice from the Editors, an anonymous referee, Martin Browning, Pierre-André Chiappori, Costas Meghir and Howard Reed. It would have been difficult to complete the project so quickly without Ian Walker’s UK tax and benefit program for Stata. Financial support from the Economic and Social Research Council is greatly appreciated. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

A Personal income taxation in the UK

B Family Credit vs. Working Families’ Tax Credit

Table Table A2 shows the difference in values of credits and applicable amounts between Family Credit in April 1998 and WFTC in June 2001. The latter include several additional reforms since the introduction of the WFTC in October 1999 which further increased the generosity of payments.

C Estimating preferences of single individuals

Table A3 presents estimates of utility function parameters for single individuals. These parameters are used for individuals in couples in the calibration exercise presented in this paper. The estimation was conducted using the random parameter logit model taking the utility function to be of the LES type.

The minimum level of leisure in the utility function \( \left( {\bar l_i } \right) \) was derived from information from the National Statistics Omnibus Survey time use module (May, 1999), while for the minimum level of consumption \( \left( {\bar c_i } \right) \) we used information from the FRS. The latter was done in two stages. First we calculated cmin, the overall minimum level of disposable income over available hours choices for the whole sample. Because \( (c - \bar c) \) must be positive, the value of \( \bar c \)had to be less than the value of the possible minimum level of disposable income cmin. We found this difference (c0) using a grid search over various levels of c0<0, such that \( \bar c = c_{\min } + c_0 \). The grid search based on the value of log likelihood in estimation of preferences produced values for c0 equal to—£33.30 per week for men and—£16.50 per week for women. In the calibrations for couples \( \bar l_i \) was also based on the National Statistics Omnibus Survey. The minimum consumption levels for men and women were kept at the same level as for singles in the case of couples without children. For couples with children the minimum values of consumption were increased to take account of the universal Child Benefit payments.

D Family Resources Survey data, 1998/99

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Myck, M., Bargain, O., Beblo, M. et al. The Working Families’ Tax Credit and Some European Tax Reforms in A Collective Setting. Rev Econ Household 4, 129–158 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-006-0003-6

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-006-0003-6