Abstract

This paper presents a structural labour supply model for the Netherlands. The model uses a large, rich data set which allows for precise estimates of labour supply elasticities for several subgroups. We use an advanced tax benefit calculator to calculate households’ budget constraints accurately. Both the large, rich data set and the advanced tax benefit calculator enable us to perform more accurate policy predictions. Simulations show that labour supply elasticities differ among subgroups. Labour supply elasticities for men in couples are low but labour supply elasticities are much higher for cohabiting/married women. Furthermore, elasticities are relatively high for individuals with a lower education and/or non-Western background. Policy simulations provide two important insights. First, an introduction of either a pure flat tax, or an income-neutral flat tax, decreases aggregate labour supply. Second, an EITC for working parents is more effective in stimulating aggregate labour supply than an EITC for all workers or an overall reduction in marginal tax rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

An ageing population and the great recession impose challenges for the sustainability of public finances. An important way to retain fiscal sustainability is to increase labour force participation. Over the past decade, the Dutch government proposed several reforms on earned income tax credits (EITCs) in order to stimulate labour force participation. In addition, there has been an ongoing discussion on the desirability of a flat tax rate in the Netherlands. There is an extensive international literature on labour supply effects of EITCs (Brewer et al. 2006; Eissa and Hoynes 2004) but these studies do not compare the relative effectiveness of EITCs targeted at several subgroups. It is important to know which EITC is most promising in boosting employment. A flat tax has often been topic of economic research as well (Aaberge et al. 2000; Fuest et al. 2008) but these studies do not estimate labour supply responses for several subgroups separately. However, in order to assess these reforms, it is crucial to have a thorough understanding of how several subgroups respond to financial incentives.

We use a discrete choice model (Van Soest 1995) for labour supply to analyze several tax reforms in the Netherlands. The main advantage of discrete choice models is their ability to cope with budget constraints that are highly nonlinear and non-convex due to the tax and benefit system. For that reason, discrete choice models are often used to evaluate ex-ante labour supply effects of policy measures.Footnote 1 We use large, rich data from the Netherlands Housing Research WOON for 2005 (In Dutch: Woononderzoek Nederland) to estimate preferences over income and leisure for several subgroups, and to simulate tax benefit reforms targeted at specific subgroups.

Our main findings are as follows. First, we find that labour supply elasticities differ across subgroups. Labour supply elasticities are relatively low for men but relatively high for women. Furthermore, individuals with a lower education and/or non-Western background have a relatively high labour supply elasticity. This is mostly due to differences in participation rate among these subgroups. The response at the extensive margin (i.e. participation) is more important than the reponse at the intensive margin (i.e. hours per employed). Second, the recent reform on EITC for working parents with a youngest child up to 12 years of age increases labour supply. The Dutch government raised the level, and the income dependency, of this EITC in the period 2006–2009. Third, an EITC for working parents is more effective in stimulating labour supply than an EITC for all workers or an overall reduction of marginal tax rates. The reason for this is that an EITC for working parents is targeted at secondary earners/single parents who are relatively elastic with respect to labour supply. Finally, simulation results show that both a pure flat tax, with increasing income equality, and an income-neutral (as measured by the Gini coefficient) flat tax decrease labour supply.

This paper contributes to the literature in the following ways. We use a rich, large data set enabling us to estimate several subgroups separately. We have 34,183 individuals in our data set and estimate utility functions separately for singles without children, single parents, couples without children and couples with children.Footnote 2 This makes our estimation more flexible and precise. Many related studies focus on a single group (e.g. Blau and Kahn 2007) or pool subgroups due to the low number of observations (e.g. Bargain et al. 2014). Estimation results show that labour supply elasticities differ among subgroups. This level of detail enables us to perform highly accurate policy simulations. Another contribution is that the labour supply model is based on a highly advanced tax benefit calculator MICROS, which calculates households’ budget constraints very accurately.Footnote 3 By contrast, most labour supply studies are based on tax benefit models with a more simplified tax and social security system. An example is the study by Van Soest and Das (2001). In MICROS, the tax and social security system is modelled in much more detail enabling more accurate policy simulations. MICROS uses a detailed and comprehensive gross / net module that takes pension contributions, social security contributions, tax credits, wealth, health insurance premiums, tax benefits of many tax deductions (for instance mortgage interests, health costs) and several means tested benefits (such as subsidies for rents and healthcare costs) into account. Hence, the budget constraint is based on more detailed information on income than for instance the EU-SILC data set which is used by Bargain et al. (2014). Finally, this study also has relevance for the current policy debate in the Netherlands. Recently there was much debate, among politicians and in the media, about the employment effects of the government’s new tax plan for 2016. The aim of the tax plan is to create more employment by reducing the tax burden on labour with 5 billion euro.Footnote 4 Important policy measures in the tax plan are (1) a reduction in the marginal tax rates, (2) a higher EITC for all workers and (3) a higher EITC for working parents. This paper compares the relative effectiveness of these policy measures in stimulating labour supply.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 presents the underlying theory of the labour supply model. Section 3 describes the dataset and Sect. 4 describes the tax system in the Netherlands. Section 5 discusses estimation results and labour supply elasticities. Labour supply effects of several tax reforms are presented in Sect. 6. Section 7 concludes. Additional information can be found in the Appendices.

2 Structural Model

This section sets out the structural labour supply model. The model does not only focus on the decision of individuals to work more or less (intensive margin) but also on the decision to participate or not (extensive margin). For non-working individuals we do not observe wage rates in the sample and we have to estimate these wages. “Appendix 1” describes the theory and estimation results of the wage estimation.

Starting point of the analysis is an individual who maximizes utility with respect to leisure and income, taking a budget constraint into account. The budget constraint is as followsFootnote 5:

Income (y) equals the product of net wage (w) and labour supply (h) added to non-labour income (\(y^{non})\), such as income from wealth and family allowances. Here, the following time restriction holds: \(h+l=\) 80, where l represents hours of leisure per week.Footnote 6 An individual chooses a combination of income (y) and leisure (l) that maximizes utility. We use the following log quadratic utility function, where income and leisure are in natural logarithms:

with \(s= \{male, female\}\). Total utilily, U(y, l), consists of a deterministic term, u(y, l), and an error term (\(\epsilon \)) drawn from an extreme value distribution (McFadden 1978). An advantage of the log quadratic utility function is its flexibility.Footnote 7

The utility function contains terms for income and leisure and several interaction terms. We allow the preference for leisure to vary over observable characteristics X like age and the presence of (young) children. We include a quadratic term for age since we expect that the relationship between age and the preference for leisure is not constant. The utility function also includes fixed costs of work (\(fc_{s}\)), for men and women separately. We include fixed costs of work as indicator variablesFootnote 8 and interact them with observable characteristics (X) such as education, ethnicity and region. The fixed costs specification provides us with a better prediction of the labour supply distribution (Euwals and Van Soest 1999). Finally, the utility function takes unobserved heterogeneity (\(\mu )\) with respect to the preference of leisure into account.

An individual chooses from a discrete choice set \(L\in \{L=1,\ldots J\}\). Individuals choose from 6 labour supply options (0, 8, 16, 24, 32 or 40 h of work)Footnote 9 and individual i prefers labour supply option k if utility in k is higher than the utility of all other alternatives:

\(i= 1,\ldots N\) individuals, \(j=1,\ldots J\) alternatives and \(k=1,\ldots J\) alternatives (\(k\ne j)\). The error terms (\(\epsilon \)) follow an extreme value distribution. McFadden (1974) showed that in this case the probability for alternative k, \(p_{k_{i} } \), for individual i equals:

The additional random term \(\mu \) for unobserved heterogeneity in Eq. 2 complicates the estimation. In addition, we estimate wages for non-workers in our sample (see “Appendix 1”) and take R draws from the wage distribution. The likelihood function has no closed form solution and therefore we use simulated maximum likelihood. For each draw of the random term \(\mu \) we calculate the likelihood and then take the average of the likelihood over R draws.Footnote 10 The following likelihood is then maximized:

We use Halton sequences to draw the random terms. They provide better coverage of the distribution than pseudo-random draws for finite samples (Train 2003).Footnote 11

3 Data

We use data from the Netherlands Housing Research WOON (In Dutch: Woononderzoek Nederland) for 2005. WOON is a large representative Dutch housing survey.Footnote 12 Our data set is supplemented with administrative income data from the Dutch Tax Office. The survey contains approximately 65,000 households. Besides general information such as age, education, ethnicity, presence of children and the number of working hours, gross income of all household members is known as well. Furthermore, gross income is known for different sources of income, such as wages, profits and various benefits (including social assistance, unemployment benefits, disability benefits and pensions). In addition, the survey also contains information about wealth, rent, mortgages, health care expenditures and several tax deductions (including medical expenses and interest paid on mortgages).

We include individuals between 23 and 60 years of age. Self-employed individuals and their partners are excluded from our sample since their number of working hours is unknown. Gross income is observed in the sample and hourly wages of workers are calculated by dividing gross annual labour income and working hours per week. We also exclude individuals with multiple sources of income (for example wages and profits) since their budget constraint is too complex. Non-working individuals are included in the sample, but only if they receive social assistance or no income. Individuals with unemployment benefits are not included in the sample since we do not have information on job search behaviour and therefore cannot identify whether these individuals are involuntary unemployed or not.Footnote 13 Finally, disabled individuals are also excluded.Footnote 14

“Appendix 2” presents descriptive statistics for the subgroups we consider. Here, Table 11 shows descriptive statistics for singles without children and single parents. We see that non-employed singles are relatively low educated (65.9 %), whereas the share of employed singles with a low education is much lower (33.7 %). Furthermore, non-employed singles are more likely to have a non-Western background (28.9 %) than employed singles (8.4 %). A similar pattern arises for single parents. Finally, the participation rate of single parents is relatively low (58.0 %) compared to singles without children (83.2 %).

Table 12 shows descriptive statistics for couples without children. As expected, most men participate on the labour market (95.2 %) and the average number of working hours is high (36.9 hours per week). Again we see that lower educated individuals and non-Western immigrants are less likely to participate on the labour market. Table 13 shows that the average number of working hours is lower for women with children (15.7 hours per week in Table 13) than for women without children (22.5 hours per week in Table 12). In the Netherlands, the average participation rate of women is relatively high compared to other OECD countries (OECD 2013). However, employed women work 5–10 hours per week less on average compared to other OECD countries (OECD 2013).

4 Institutional Setting

Labour income is taxed progressively at the individual level in the Netherlands. Table 1 shows marginal tax rates in 2005. Marginal tax rates increase as taxable personal labour income increases. The marginal tax rate is 34.4 % in the first tax bracket (0–16,893 euro) and rises to 52 % in the fourth bracket (>51,672 euro).

The Dutch tax system contains several tax credits and Table 2 illustrates the most important tax credits. Non-working individuals and employees in the Netherlands are entitled to a general tax credit of 1894 euro.Footnote 15 Individuals not paying taxes can transfer this general tax credit to their spouses.Footnote 16

The Dutch tax system contains four important EITCs for employees in 2005. First, an EITC for all workers (irrespective of the presence of young children).Footnote 17 The level of this EITC rises with income at a (phase-in) rate of 11.9 %, until the maximum of 1287 euro is reached. Second, an EITC for working single parents with a youngest child up to 16 years.Footnote 18 This EITC rises with personal income at a (phase-in) rate of 4.3 % and the maximum EITC equals 1401 euro in 2005. Third, primary earners with a youngest child up to 12 years earn a fixed EITC of 228 euro.Footnote 19 Fourth, secondary earners and single parents with a youngest child up to 12 years receive a fixed EITC of 617 euro.Footnote 20 In order to receive the EITC for primary earners and the EITC for secondary earners/single parents, personal income must exceed an income threshold 4368 euro. The Dutch government raised the budget of the EITC for secondary earners by 0.5 billion euro over the period 2006–2009, in order to increase labour force participation of secondary earners and single parents.

The social security system is complex in the Netherlands. The tax benefit model MICROS not only calculates taxes and tax credits, but takes pension contributions, social security contributions, income from wealth, and health insurance premiums into account as well. In addition MICROS determines tax benefits of various tax deductions, like mortgage interests and health care costs, and adds these tax benefits to net income. Finally, MICROS calculates various means tested benefits such as subsidies for rents. By taking all relevant elements of the Dutch tax system into account, MICROS calculates budget constraints very accurately. The recent study by Bargain et al. (2014) uses the tax benefit model EUROMOD to calculate the budget constraints. Although EUROMOD simulates quite a detailed tax and benefit system for the Netherlands, it misses important information.Footnote 21 First, EUROMOD ignores non-take-up of several benefits, such as rent allowance. Consequently, EUROMOD overestimates the number of recipients of rent allowance. Second, EUROMOD misses several tax deductions at the individual level, such as health care costs, study costs and gifts to charities.

Figure 1 shows the non-linear budget constraint for a single parent with an hourly gross wage of approximately 16 euro. The presence of a child younger than 12 years implies that the single parent receives the EITC (for all workers), the EITC for single parents and the EITC for secondary earners/single parents.

5 Estimation Results

5.1 Singles

We estimate preferences separately for singles without children and single parents. “Appendix 3” gives the estimated parameters for these subgroups. The number of observations is 5766 and 1333 for singles without children and single parents, respectively. Estimation results show that the standard deviation of the Halton draws (\(\sigma \)) for unobserved heterogeneity is not significant and close to zero for both subgroups. Therefore, we restrict its value to zero in the estimation. Young singles and single parents have a higher preference for work since marginal utility of leisure, with respect to age, is negative. This relationship is reversed for older singles and the quadratic term starts to dominate at an age of 32 years.Footnote 22 For single parents, the quadratic term already dominates at an age of 19 years. Females and/or single parents with a youngest child (0–3 years of age) have a higher preference for leisure.

The fixed costs specification contains a constant term and some interaction terms. The constant term of the fixed costs specification is negative and significantly different from zero, which means that there is some disutility from work, such as travelling costs, search costs or childcare costs.Footnote 23 Singles and single parents, with a lower education and/or a non-Western background, have higher fixed costs of participation. We also include a dummy for the Western region, which is characterized by relatively high economic activity, in the fixed costs specification. The coefficient is positive and significant for single parents.Footnote 24

An important consideration in our labour supply model is that the quadratic utility function is not automatically quasi-concave for all values of income (y). This is not a problem as long as the utility function is quasi-concave for the observed combinations of income and leisure in the sample. This condition is fulfilled for all singles and single parents in the sample.

“Appendix 4” shows that the model predicts the labour supply distribution well. We simulate labour supply elasticities by increasing gross wages by 10%. Table 3 gives elasticities for singles and single parents with the standard errors between parentheses. The labour supply elasticity is 0.19 for singles without children which means that singles increase their labour supply by 0.19 percent as gross wages increase by 1 percent. Single parents are relatively elastic with respect to labour supply: 0.27. The extensive margin is the increase in the participation rate whereas the intensive margin refers to change in hours worked by the employed. Table 3 shows that the extensive margin is more important here.

5.2 Couples

Table 15 in “Appendix 3” contains the parameters of the utility function for couples. We split the couples into groups without children (5562 households) and with children (7980 households). Here, we also include a third order term for leisure to improve the fit of the model in terms of predicting the labour supply distribution. Table 15 illustrates that leisure is a normal good for men and women since the coefficients of the interaction terms of leisure with income are positive. Marginal utility of income is positive for all households at the observed labour supply choices. We see that younger individuals have a higher preference for work (i.e. marginal utility of leisure negative) whereas older individuals have a higher preference for leisure (i.e. marginal utility of leisure positive).Footnote 25 The presence of young children (0–4 and 4–11 years) raises the preference for leisure.Footnote 26

We estimate fixed costs of work separately for men and women. The fixed costs specification contains a constant term and interaction terms with education, ethnicity and a dummy for the Western region.Footnote 27 Fixed costs are higher for men and women with a lower education and/or non-Western background. Women living in the Western region of the Netherlands have lower fixed costs of work. Finally, the estimated standard deviation of the random terms for leisure are highly significant for men (\(\sigma _1\)) but not for women in couples (\(\sigma _2\)). We restrict the standard deviation at zero in the estimation.

Table 4 shows elasticities with the standard errors in parentheses. Elasticities for men are low. Elasiticities for women are much higher, 0.39 for women without children and 0.51 for women with children. The extensive margin is more important for women in couples than the intensive margin. Furthermore, cross elasticities are negative and substantial for women in couples.

“Appendix 5” shows that the results are robust with respect to the functional form of the utility function. Elasticities for singles, single parents and men and women in couples are similar whether we use a log linear, quadratic or log quadratic utility function. We have also experimented with the number of discrete choices and this hardly affects the results. Estimating nested models, with less interaction terms in the fixed costs specification or less interactions terms with leisure, does result in higher elasticities for single parents and women in couples. However, likelihood ratio tests show that the models in Tables 14 and 15 are preferred over these alternative models. The same holds for the richest fixed costs specification, where we also include interaction terms for age and the presence of children (not significant). Finally, “Appendix 5” shows that calibrating the error terms (Creedy and Kalb 2005) yields similar elasticities. Utility consists of a deterministic term and a random term. Calibration means that we draw these random terms from a distribution and only accept those draws for which the observed outcome has the highest utility.

5.3 Elasticities for Subgroups

It is crucial to have a thorough understanding of how subgroups respond to financial incentives for an optimal design of the tax benefit system. In the Netherlands for instance, several EITCs are targeted at specific subgroups (see Sect. 4). We construct subgroups based on characteristics like age, education and ethnicity and then simulate elasticities for these subgroups. These subgroups are expected to respond differently to financial incentives (Bargain et al. 2014). Table 5 gives labour supply elasticities by subgroups in our sample. Individuals with a lower education and/or non-Western background have relatively high labour supply elasticities compared to individuals with a higher education and Western background. These differences are primarily driven by differences in participation rates. Differentation based on the age of the youngest child and the individuals’ age gives mixed results. Single parents with preschool children (0–3 years of age) are relatively elastic with respect to labour supply and labour supply elasticities fall as the youngest child gets older. However, we do not find such a pattern for women in couples with children. Labour supply elasticities for women with younger children are similar to those for women with older children. Finally, older singles and women in couples without children respond more strongly to an increase in gross wages than their younger counterparts. For single parents the opposite holds. Single parents younger than 40 years of age have a relatively high labour supply elasticity compared to older single parents.

5.4 Comparison with Literature

We find that elasticities are low for men in couples but considerably higher for women in couples, in particular when young children are present. Elasticities of singles and single parents are in between. Our simulated elasticities are in line with related studies. However, most studies focus only on couples while this study also estimates behavioural responses of singles and single parents. A recent study by Bargain et al. (2014) estimates elasticities for singles, but they have to pool singles and single parents due to the low number of observations.

Studies by Van Soest and Das (2001) and Nelissen et al. (2005) estimate labour supply elasticities for cohabiting/married women in the Netherlands. Both studies find somewhat bigger elasticities for women in couples. However, they use older data in which the participation rate was relatively high. Participation rates have increased over time and labour supply elasticities fell. Blau and Kahn (2007) show that labour supply elasticities for women (in couples) fell from 0.8 in 1980 to 0.4 in 2000. Heim (2007) finds a similar result. Finally, Bargain et al. (2014) estimate elasticities for several European countries and the US. They estimate a relatively high elasticity for women in couples (0.2–0.6 across countries), whereas elasticities for men in couples are rather low (0.05–0.15 across countries). They show that countries with a relatively high participation rate have relatively low labour supply elasticities.

We also find that the extensive margin is more important than the intensive margin for women in couples and this is in line with other studies (Bargain et al. 2014). Cross elasticities are negative and substantial for women in couples. The same result is found by Bloemen (2009, 2010).

6 Policy Simulations

This section presents the results of several policy simulations. Section 6.1 shows labour supply effects of two recent reforms on tax credits in the Netherlands. Next, Sect. 6.2 considers the effectiveness of several policies to increase labour force participation. Finally, Sect. 6.3 shows labour supply effects of a possible introduction of a flat tax system in the Netherlands.

6.1 Recent Reforms of Tax Credits

Over the past decade, the Dutch government took several measures in order to increase labour force participation. We simulate two important reforms.

The first reform is the reform of the EITC for working parents (in Dutch: Inkomensafhankelijke Combinatiekorting). Working parents with a youngest child up to 12 years of age, are entitled to this EITC. The Dutch government raised the budget for this EITC over the period 2006–2009. Here, the level and income dependency of the EITC is raised and the EITC is targeted only on secondary earners/single parents. Primary earners do not receive this EITC in 2009.Footnote 28 Figure 2 shows the structure of the EITC in 2005 and 2009, where personal taxable income is located on the horizontal axis and the vertical axis shows the level of the EITC. Starting from an individual income of 4368 euro, the EITC increases with a rate of 3.8 % until the maximum of 1722 euro is reached.Footnote 29 Calculations with MICROS show that the public expenditures on the EITC is approximately 1.1 billion euro.Footnote 30 Approximately 1 out of 7 million working individuals receive the EITC for working parents.

The second large reform is the removal of the transferability of the general tax credit (in Dutch: Beperking overdraagbaarheid algemene heffingskorting). Individuals receive a general tax credit of 1894 euro in 2005. Non-working individuals, or secondary earners who do not pay enough taxes, can transfer this tax credit to their partners. The transferability of the general tax credit reduces the financial incentive of non-working partners to supply labour. In order to stimulate labour force participation, the Dutch government restricted this transferability of the general tax credit in 2007 (Coalition Agreement, 2007). At first in 2009, the transferability was only reduced for individuals born after 1971 and without young children (0–6 years old). In 2012, the Dutch government reduced the transferability of the general tax credit for a broader group by lowering the age criterion (from 1971 to 1963) and abolishing the exemption for individuals with young children. The transferability of the tax credit is reduced in yearly steps in order to smooth negative income effects. The structural situation in which transferability is completely abandoned is reached in 2024. In that case, individuals can only cash the individual tax credit if they pay enough taxes.

A budgetary calculation with MICROS shows that the total budget of the transferability of the general tax credit is 1.9 billion euro in 2005. Approximately 1.2 million couples (out of 4.1 million couples) transfer the general tax credit to their partner. A complicating factor here is that the level of social assistance is linked to the net minimum wage, which in turn takes the general tax credit into account. In fact, the general tax credit is included twice in the net minimum wage since, under the old system, this tax credit can be transferred to a partner. In order to prevent inequality between working individuals (with only 1 general tax credit in the structural situation) and recipients of social assistance (still with 2 general tax credits in the structural situation), the Dutch Coalition decided to reduce the extra general tax credit in net minimum wage in yearly steps as well. For couples, net income of social assistance falls by 1894 euro (in 2005 prices) in the structural situation. Single parents receive 90 % of the net minimum wage, whereas singles without children only receive 70 % of net minimum wage. Consequently, social assistance’s net income falls by 1705 and 1326 euro for single parents and singles without children respectively. MICROS estimates that the Dutch government saves 0.5 billion euro on social assistance’s budget in the structural situation, deflated to 2005 prices.

Table 6 shows the labour supply effects of both reforms. We present labour supply effects as percentage changes in working hours. Column (1) shows the effect of the EITC for working parents. Singles and couples without children are unaffected by this EITC reform. Single parents increase their labour supply with 1.3% on average, whereas women in couples increase their labour supply by 3.2 %. The reason for this relatively large response is that a large majority of secondary earners are women. Most Dutch women work part time (see Figs. 5b, 6b in “Appendix 4”). Policy simulation shows that the extensive margin is the main driving force behind the increase in the labour supply of women. The bottom part of Table 6 shows that total labour supply increases by 0.5 % (15,300 FTEs).

Column (2) in Table 6 shows the labour supply effects of the removal of the transferability of the general tax credit, under the assumption that the level of social assistance remains fixed. Only couples are affected by this reform. Table 6 shows that men in couples hardly adjust their labour supply, which is consistent with having a low labour supply elasticity. More importantly, most men work full time and pay enough taxes to cash the general tax credit themselves. Labour supply for women in couples without and with children increases by 3.4 and 5.7 %, respectively. Again we see that the extensive margin is important here. The intensive margin is negative on average which is due to a composition effect. Women who enter the labour force prefer small part time jobs, pulling down the average number of working hours. Total labour supply increases by 1.2 % (36,300 FTEs).

As stated earlier, the Dutch government decided to remove the transferability of the general tax credit in the net minimum wage as well. This lowers the level of social assistance and strongly increases the financial incentive to supply labour. The final column in Table 6 shows that the extensive margin increases labour supply further, as expected. The increase in labour supply is relatively strong for singles. For couples, labour supply effects are only slightly higher compared to the scenario in which the level of social assistance is fixed. This is intuitively appealing since the number of singles with social assistance is relatively high compared to couples: 75 % of households in the sample with social assistance are single. Overall, labour supply increases with 3.0 % (91,500 FTEs).

The reform on the EITC for working parents costs 1.1 billion euro ex-ante. Ex-post budgetary simulations show that the increase in labour supply due to the EITC, raises tax revenues by 0.2 billion euro. Hence, the EITC costs 1.1 billion euro ex-ante but only 0.9 billion euro ex-post. Elimination of the transferability of the general tax credit results in 0.3 billion euro in additional tax revenues, thereby increasing the ex-ante revenue of 1.9 billion to 2.2 billion euro. By lowering the level of social assistance as well, the government receives an additional 0.7 billion euro on tax revenues.

6.2 Effectiveness Policies to Promote Labour Force Participation

As in many OECD countries, the Dutch tax system contains many policy schemes that aim to increase labour force participation. It is important to know which policy is most effective in stimulating labour supply. We simulate three of these policies to study their effectiveness. We simulate an ex-ante increase in 0.5 billion euro in each of these scenarios. We study the following scenarios:

-

1.

An increase in the EITC for working parents from 1722 euro to 2500 euro. The phase-in rate increases from 3.8 to 9.5 %.

-

2.

An increase in the EITC for all workers from 1287 euro to 1387 euro. The phase-in rate increases from 11.9 to 12.8 %.

-

3.

An overall reduction in marginal tax rates. We lower marginal tax rates in all tax brackets by 0.2 % points.

The EITC for working parents focuses on the smallest group because only secondary earners and single parents, with a youngest child under 12 years, receive this EITC. The more general EITC for all employed individuals focuses on a much larger group. Primary earners also receive this EITC and the same holds for secondary earners and single parents without children.

Table 7 shows that the EITC for working parents is more effective in stimulating labour supply than a more general EITC for all workers. Overall, labour supply increases by 0.4 % which equals approximately 11,300 FTEs. The reason for this is that the EITC for working parents is targeted at secondary earners (mostly women in couples) and single parents who are relatively elastic with respect to labour supply. By contrast, the EITC for all workers is also targeted at primary earners who are relatively inelastic with respect to labour supply. The EITC for all workers (4000 FTEs) is more effective than an overall reduction in marginal tax rates (2200 FTEs). The increase in the EITC is fully targeted at employees whereas pensioners also partly benefit from a generic decrease in marginal tax rates.

6.3 Labour Supply Effects of a Flat Tax Rate in the Netherlands

The discussion about a flat tax already started by Hall and Rabushka (1986) and has been running for many years. Nowadays there are several countries with a flat tax, mainly in Eastern Europe. Examples are Latvia, Lithuania, Russia and Ukraine. Recently, Bulgaria (in 2008) and Hungary (in 2011) introduced a flat tax while in other countries, such as the Czech Republic and Poland, the discussion of the desirability of introducing a flat tax is on the political agenda. In the Netherlands, there is an ongoing discussion on the desirability of a flat tax system as well.Footnote 31 In 2005, the right wing liberals (VVD) proposed a flat tax system in their election program, and more recently, the Christian Democrats (CDA) included a flat tax in their program for the elections in 2012.

There are several flat tax scenarios possible, ranging from a flat tax that increases income inequality, to a more ’social’ flat tax that keeps income inequality constant. We simulate both scenarios. First, we simulate a flat tax rate of 38.3 %, which is found to keep the government budget balanced ex-ante. Second, we simulate an income neutral (as measured by the Gini coefficient) flat tax of 44.0 % where we use the additional tax receipts to compensate low income households. All individuals, who pay income taxes in the current system, receive a fixed tax credit (1300 euro) in order to compensate them for the higher marginal tax rate.

Table 8 shows the labour supply effects of a flat tax of 38.3 % in the Netherlands. Labour supply of singles, with or without children, decreases. For men in couples, the effect is small and close to zero. The largest effect is found for women in couples. Overall, labour supply decreases by 0.4 % (11,100 FTEs). Income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, increases by 6.8 %.

Men in couples hardly adjust their labour supply. Most men are primary earners and work full time. The effects are much stronger for singles, single parents and women in couples. The decline in labour supply is highest for women in couples. Women without children work 1 % less, while labour supply of women with children falls by 1.4 %. Here, the response at the extensive margin is more important than the response at the intensive margin. Many women work part-time and earn a relatively low income. Consequently, many women in couples now face a higher tax rate and stop working. The marginal tax rate for these individuals is higher with the flat tax (38.3 %) than in the current situation (34.4 %). The same holds for singles and single parents. However, there is an opposite effect on the intensive margin for most groups.Footnote 32 Employees with a relatively high income, currently paying taxes in the second tax bracket (41.95 %) or higher, now face a lower marginal tax rate. Consequently, they increase the number of working hours.

The second column of Table 8 shows the effects of the income-neutral flat tax. Labour supply falls for all groups. Singles without children work 1.4 % less and now we also see a large negative effect at the intensive margin (\(-\)0.9 %). The marginal tax rate is much higher now (44.0 %) than in the first scenario with the flat tax (38.3 %). Indeed, the marginal tax rate is even higher than the current marginal rate in the third tax bracket (42.0 %). Consequently most employed singles without children now face a higher marginal tax rate and decrease the number of working hours.

The response at the intensive margin is also negative for single parents: \(-\)2.0 %. However, there is an opposite, positive, effect at the extensive margin (1.5 %). With respect to the response at the extensive margin, it is important to distinguish two mechanmisms. First, some employees face a higher marginal tax rate and stop working. Second, the introduction of the tax credit of 1300 euro raises participation of non-employed individuals. The tax credit is only granted to individuals with labour income. At the same time the level of social assistance does not change in this scenario, so the difference between income from work and social assistance becomes larger. Recipients of social assistance thus have a stronger incentive to enter the labour market. This effect is relatively strong for single parents, because they receive social assistance relatively frequently (42 %).

A similar effect is found for women in couples with children. Approximately 31 % of women is non-employed and the introduction of the tax credit increases their participation rate. However, the negative effect at the intensive margin dominates and total labour supply falls by 1.3 %. For women without children, the response at the extensive margin is slightly negative, because the share of non-employed women is lower (26 %) than for women with children (31 %). This reduces labour supply of women with children more compared to that of women without children. On balance, labour supply decreases by 1.0 % (29,700 FTEs). Income inequality remains constant in the scenario and labour supply falls more than in the first scenario with a flat tax.

6.4 Comparison with Literature

There is an extensive international literature on labour supply effects of EITCs (Blundell et al. 2000, 2005; Brewer et al. 2006; Eissa and Hoynes 2004). Blundell et al. (2000) for instance use a discrete choice model for an ex-ante evaluation of the introduction of the Working Families’ Tax Credit (WTFC) in the UK. They estimate that replacing the family credit by the more generous WFTC increases labour supply by about 30,000 individuals. Using a difference-and-differences (DD) approach, Blundell et al. (2005) estimate that the WTFC indeed had a significant positive effect on labour force participation. The ex-post analysis shows that labour force participation increased by 25,000–59,000 individuals, depending on the type of dataset used. Brewer et al. (2006) finds a larger effect: the WFTC attracts approximately 81,000 extra workers. They also use a structural labour supply model to study the WFTC. The authors conclude that the WFTC leads to an increase in the labour supply of single mothers and men in couples by respectively 5.1 and 0.8 percentage points. The effect for women in couples is negative: \(-\)0.6 percentage points.

Eissa and Hoynes (2004) study the EITC in the US by using survey data for the period 1984–1996. The study, however, focuses only on the participation decision of couples. Herein they use both quasi-experimental method, as a structural model. Both methods show that the EITC decreases total labour force participation of couples. The decline in the participation of women is larger than the increase in the participation of men. The behavioral responses of males are limited: most men already participate and work full-time. Women react more strongly to financial incentives. But because the EITC depends on the household income, the EITC effectively subsidizes women to stay home. For some women, entering the labour market results in a lower, or complete loss, of the EITC.

Our simulated results show that the recent reforms on tax credits increase labour supply and this result is in line with results found by studies on the same reform. De Mooij (2008) simulates labour supply effects of the EITC for working parents and the transferability of the general tax credit with a calibrated, general equilibrium model for the Netherlands. However, these elasticities are not esimated on micro data. In fact, the elasticities are based on a meta analysis by Evers et al. (2008) on 32 scientific studies, 6 of which refer to the Netherlands. De Mooij (2008) concludes that the EITC stimulates labour supply of secondary earners but at the expense of primary earners’ labour supply. In addition, De Mooij (2008) concludes that a removal of the transferability of the general tax credit increases labour supply of partners in particular. Furthermore, our analysis shows that there is a strong response at the extensive margin and this result is in line with the study by Bosch and Van der Klaauw (2012). They conclude that marginal tax rates are less important and that women respond more to changes in tax allowances. Our scenario is similar in the sense that the general tax credit cannot be transferred to their partners, and consequently individuals only receive the general tax credit if they pay enough taxes. Finally, Bettendorf et al. (2012) use a DD-analysis to study labour supply effects of a joint reform on childcare and the EITC for working parents in the period 2005–2009. They find a total effect of 6.2 % for married/cohabiting women with young children.Footnote 33

Labour supply effects of a flat tax have often been topic of economic research (Aaberge et al. 2000; Fuest et al. 2008). Aaberge et al. (2000) use a discrete choice model in order to simulate labour supply effects of a flat tax rate in Italy, Norway and Sweden and conclude that a flat tax increases labour supply. Fuest et al. (2008) use a discrete choice model in order to assess labour supply effects of a flat tax in Germany. They show that a flat tax system, with a low basic allowance and a low marginal tax rate, increases total labour supply (by approximately 90,000 FTEs) but increases income inequality. In this scenario, women’s increased labour supply is at the expense of men’s labour supply. The reason for this is that taxation in Germany is at the household level, which implies that both spouses face the same effective marginal tax rate. Consequently, it is often observed that men work full time while women are not participating at all. An alternative scenario, with a higher flat tax rate and a higher basic allowance, does not generate a significant change in labour supply and income inequality.

Until now, labour supply effects of a flat tax in the Netherlands were only simulated with a general equilibrium model (Jacobs et al. 2009). They simulate two scenarios. First, a system with a relatively low flat tax rate (38 %) that increases total labour supply by 1 %. On the one hand, primary earners and singles face lower marginal tax rates and increase their labour supply. On the other hand, secondary earners face (on average) higher marginal taxes rates and lower their labour supply. A similar story holds for non-working individuals. However, our study finds the opposite effect: labour supply decreases in our first flat tax scenario. An important difference is that the behavioural responses of Jacobs et al. (2009) are calibrated while this study estimates behavioural responses for several subgroups with Dutch data.Footnote 34 Furthermore, they only model the extensive margin for women in couples and not for singles and single parents. Second, Jacobs et al. (2009) simulate a system with a relatively high flat tax rate (43 %) in which income inequality is kept constant. In this case, labour supply falls by 0.3 %. Our analysis confirms the result that an income neutral flat tax lowers labour supply.

7 Conclusion

This paper presents a recently developed labour supply model based on the highly advanced Dutch tax benefit model MICROS. The labour supply model uses a discrete choice framework and the model does a good job at predicting the labour supply distribution for several subgroups. By using a large, rich data set we obtain precise estimates of labour supply repsonses for several subgroups. These heterogeneous responses are important for the tax reforms we consider.

As a first application, labour supply effects of two recently announced policy measures are simulated. Both the elimination of the transferability of the general tax credit and the increase in the EITC for secondary earners/single parents increase labour supply. In addition, policy simulations show that the EITC for secondary earners/single parents is more effective in stimulating labour supply than a more general EITC for all workers. Finally, an introduction of a flat tax, either with increasing income inequality or an income neutral scenario, is expected to reduce labour supply.

A limitation of this analysis is that we assume that all individuals can freely choose their preferred alternative from a discrete choice set. In reality, demand side restrictions may limit these discrete choice sets and individuals may be involuntary unemployed. However, the analysis by De Boer (2015) shows that the role of involuntary unemployment is limited in the Netherlands, at least for the period 2006–2009. The main reason for this is that the share of involuntary unemployment is low: approximately 4 % in the period 2006–2009.

Another caveat is that the labour supply model is restricted to direct labour supply effects only. In reality, an increase in labour supply may influence unions bargaining power thereby changing demand for labour and this effect is not taken into account. In order to take these effects into account, a general equilibrium model is needed which is beyond the scope of this study. However, microsimulation models are better able to demonstrate distributional effects of policy measures. A microsimulation model like MICROS allows for more heterogeneity, enabling us to focus on several subgroups based on characteristics such as the presence of children, education and/or ethnicity. Our key contribution is that we use a labour supply model, based on a large, rich data set, that allows for more heterogeneity in labour supply responses. Our analysis indeed shows that these subgroups respond differently to financial incentives. This is of crucial importance for the reforms we consider.

Notes

Creedy et al. (2002) provide a nice technical survey of behavioural microsimulation.

Which corresponds to 20,641 households.

A drawback of the analysis is that the estimation is on a cross section data set which may raise identification issues. A back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that our simulated labour supply effects of the reform on EITCs for working parents are of the same magnitude as the results found by a difference-in-difference study by Bettendorf et al. (2012) on the same reform.

Available online (in Dutch) at: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2015/06/19/belastingherziening.

The gross wage is considered fixed throughout the analysis, which is a common assumption in discrete choice labour supply models. See for instance Creedy and Kalb (2005).

Experimentation with other time endowments hardly affected the results.

Sensitivity analysis shows that the choice of the functional form hardly affects the results (see “ Appendix 5”).

Which equal zero for the non-working alternative and one for all the working alternatives.

Discretized as 0=[0,5], 8=[6,13], 16=[14,20], 24=[21,27], 32=[28,34], 40=[35,.).

The simulated maximum likelihood (SML) estimator is consistent if N (number of individuals) and R (number of draws) tends to infinity. Moreover, if \(\sqrt{N/R} \rightarrow 0\) then the SML estimator is asymptotically equivalent to the ML estimator (see Cameron and Trivedi 2005).

Haan and Uhlendorf (2006) provide a good description of Stata routines for simulated maximum likelihood and Halton draws.

The Netherlands Housing Research is a survey that includes information on housing conditions of households, including housing costs.

The reason for this is that part of the disabled individuals is permanently disabled, with no prospect of recovery, and it is not possible to distinguish between permanently or temporarily disabled individuals in our sample.

In Dutch: Algemene heffingskorting.

In 2009 the transferability of the general tax credit is stepwise reduced until transferability is completely abandoned in 2024.

In Dutch: Arbeidskorting.

In Dutch: Alleenstaande ouderkorting.

In Dutch: Combinatiekorting.

In Dutch: Aanvullende combinatiekorting.

An extensive country report for the Netherlands is available at: https://www.euromod.ac.uk/using-euromod/country-reports.

Since exp\((4.419/(2*5.382))*21 = 32.\)

Childcare costs are not observed in our data set.

The dummy is not significant for singles without children and therefore excluded from the regression.

Where the tipping point for men and women without children is at an age of approximately 40 and 41 years respectively. For couples with children, the quadratic terms dominates at an age of approximately 35 years for men and 36 for women.

The reference category is a dummy with the youngest child aged 12 years or older.

Fixed costs do not differ significantly for lower and higher educated men without children, so we dropped this interaction term in the fixed costs specification for men without children. The same holds for the interaction term of the Western region in the fixed costs specification for men.

In 2005, the EITC is a fixed amount of 228 euro for primary earners and 617 euro for secondary earners/single parents.

Deflated to 2005 prices.

MICROS is highly representative for the Dutch population and budgetary calculations are in line with official statistics by the Dutch Ministry of Finance and Statistics Netherlands.

The only exception here are single parents for which the effect at the intensive margin is negative (\(-\)0.1 %).

The increase in the budget of the EITC is approximately one third of the increase in the childcare budget. Assuming that both policies are about equally effective in stimulating labour supply, a back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that our simulated result is broadly in line with the result found by Bettendorf et al. (2012).

Which equals exp(0.089).

References

Aaberge, R., Colombino, U., & Strom, S. (2000). Labor supply responses and welfare effects from replacing current tax rules by a flat tax: Empirical evidence from Italy, Norway and Sweden. Journal of Population Economics, 13(4), 595–621.

Bargain, O., Orsini, K., & Peichl, A. (2014). Comparing labor supply elasticities in Europe and the United States. Journal of Human Resources, 49(3), 723–838.

Bettendorf, L., Jongen, E., and Muller, P. (2012). Childcare subsidies and labour supply: Evidence from a large Dutch reform. CPB Discussion Paper 217, The Hague.

Blau, D., & Kahn, L. (2007). Changes in the labor supply behavior of married women: 1980–2000. Journal of Labor Economics, 25(3), 393–438.

Bloemen, H. (2009). An empirical model of collective household labour supply with non-participation. Economic Journal, 120(543), 183–214.

Bloemen, H. (2010). Income taxation in an empirical collective household labour supply model with discrete hours. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper 10–010/3, Amsterdam.

Blundell, R., Brewer, M., & Shephard, A. (2005). Evaluating the labour market impact of working families’ tax credit using difference-in-differences. Institute for Fiscal Studies, London: Technical report.

Blundell, R., Duncan, A., McCrae, J., & Meghir, C. (2000). The labour market impact of the working families tax credit. Fiscal Studies, 21(1), 75–104.

Bosch, N. and Van der Klaauw, B. (2012). Analyzing female labor supply - evidence from a Dutch tax reform. Labour Economics, 19.

Brewer, M., Duncan, A., Shephard, A., & Suarez, M. (2006). Did working families’ tax credit work? The impact of in-work support on labour supply in Great Britain. Labour Economics, 13, 699–720.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Council of Economic Advisors (2005). De noodzaak van grondslagverbreding in het Nederlandse belastingstelsel. www.tweedekamer.nl.

Creedy, J., Duncan, A., Harris, M., & Scutella, R. (2002). Microsimulation modelling of taxation and the labour market: The Melbourne Institute Tax and Transfer Simulator. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Creedy, J., & Kalb, G. (2005). Discrete hours labour supply modelling: Specification, estimation and simulation. Journal of Economic Surveys, 19(5), 697–738.

De Boer, H.-W. (2015). A structural analysis of labour supply and involuntary unemployment in the Netherlands. CPB Discussion paper.

De Mooij, R. (2008). Reinventing the dutch tax-benefit system: Exploring the frontier of the equity-efficiency trade-off. International Tax and Public Finance, 15, 87–103.

Eissa, N., & Hoynes, H. (2004). Taxes and the labour market participation of married couples: The earned income tax credit. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1931–1958.

Euwals, R., & Van Soest, A. (1999). Desired and actual labour supply of married men and women in the netherlands. Labour Economics, 6, 95–118.

Evers, M., de Mooij, R., & van Vuuren, D. (2008). The wage elasticity of labour supply: A synthesis of empirical estimates. De Economist, 156(1), 25–43.

Fuest, C., Peichl, A., & Schaefer, T. (2008). Is a flat tax reform feasible in a grown-up democracy of Western Europe? A simulation study for Germany. International Tax and Public Finance, 15, 620–636.

Gradus, R. (2009). Flat but fair: A proposal for a socially conscious flat tax rate. European View, 9(2), 279–280.

Gradus, R., Beetsma, R., Bovenberg, L., Caminada, K., Dijkgraaf, E., and Eijffinger, S. (2012). Elke Nederlander gebaat bij sociale vlaktaks. www.mejudice.nl.

Haan, P., & Uhlendorf, A. (2006). Estimation of multinomial logit models with unobserved heterogeneity using maximum simulated likelihood. The Stata Journal, 6(2), 229–245.

Hall, R., & Rabushka, A. (1986). The flat tax. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 3, 598–607.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specifcation error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Heim, B. (2007). The incredible shrinking elasticities: Married female labor supply, 1978–2002. Journal of Human Resources, 42(4), 881–918.

Jacobs, B., De Mooij, R., & Folmer, K. (2009). Analyzing a flat tax in the Netherlands. Applied Economics, 42(25), 3209–3320.

McFadden, D. (1974). Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In P. Zarembka (Ed.), Frontiers in econometrics (pp. 105–143). New York: Academic.

McFadden, D. (1978). Modeling the choice of residential location. In A. Karlqvist, L. Lundqvist , F. Snickars & J. Weibull (Eds.), Spatial Interaction Theory and Planning Models (pp. 75–96). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Nelissen, J., Fontein, P., & van Soest, A. (2005). The impact of various policy measures on employment in the Netherlands. Japanse Journal of Social Security Policy, 4(1), 17–32.

OECD (2013). Labour Force Statistics. Paris.

Train, K. (2003). Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van Soest, A. (1995). Structural models of family labor supply: A discrete choice approach. Journal of Human Resources, 30(1), 63–88.

Van Soest, A., & Das, M. (2001). Family labour supply and proposed tax reforms in the Netherlands. De Economist, 149, 191–218.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I have benefitted from comments and suggestions by two anonymous referees, Hans Bloemen, Egbert Jongen and participants of the IMA conference in Stockholm June 2011.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Wage Estimation Heckman Selection Model

Gross wages are unknown for non-working individuals and we impute these wages. This Appendix describes the theory and estimation results of this wage estimation. We use the observed wage distribution of workers in the sample. We estimate the determinants of gross wages for this group and use these results to estimate expected gross wages for non-working individuals. Here, we have to consider a (possible) selection effect. The population of workers probably differs from the non-working population in an unmeasurable way. By using the so-called Heckman selection model (Heckman 1979), we can correct for potential selection bias. The Heckman selection model consists of a wage equation and participation equation. The wage equation for the natural logarithm of gross hourly wage is as follows.

where \(x_{i}\) is a vector with several dummies for education, age, age squared, a dummy for non-Western immigrant and a dummy for the Western region for individual i. The residuals \(\epsilon _{i}\) are assumed to be normally distributed with mean 0 and variance \(\sigma ^2\). We estimate the vector \(\beta \) of the wage equation by OLS.

The participation equation estimates the probability of participation, using a probit regression:

where \(z_{i}\) is a vector with several dummies for education, dummies for the presence of children, age, age squared, a dummy for non-Western immigrant and a dummy for the Western region as explanatory variables. The unexplained portion is equal to \(\mu _{i}\), and we assume that \(\mu _{i}\) is (standard) normally distributed. It is expected that individuals with a higher education have a higher probability of participation and receive higher wages on average. A similar story holds with respect to age. However, the positive relationship between age and participation (and wages) is expected to weaken when individuals become older (diminishing returns). Furthermore, dummies for Non-Western immigrants (negative relationship) and Western region (positive relationship) are included as well. Finally, one expects that the presence of children lowers the probability of participation.

The vector \(\gamma \) (Eq. 7) contains coefficients of the participation equation. The correlation between the two error terms of the wage equation (\(\epsilon \)) and participation equation (\(\mu \)) equals rho (\(\rho \)). That is, rho is the correlation between unobserved determinants of both equations. If rho is positive, it means that unobserved characteristics are positively correlated. Talent for instance has a positive effect on the gross wage and the probability of participation, with a positive rho as a result. If rho is negative, then there are unobserved characteristics that have a positive impact on participation, but a negative effect on the gross wage (or vice versa). If rho is equal to 0, then the error terms are independent and selection bias is not present.

The conditional expected value of the gross hourly wages (that is, provided that the individual works) can be approximated by:

where

The second term on the right hand side of the equation is the Inverse Mill’s Ratio. Here \(\phi \) is the probability density function whereas \(\Phi \) represents the cumulative probability density function. Both functions use the vector of explanatory variables (\(z_{i}\)) as input for each individual. The participation equation ensures that the effect of the characteristics (\(z_{i}\)) from the participation equation on wages is taken into account. That is, a correction is made for selection bias.

The Heckman selection model is estimated separately for single women, single men, men in couples and women in couples. Table 9 shows the results for the wage and participation equation for single men and women. Most of the coefficients of the wage equations for singles are highly significant (at 1 % level) and have the expected sign.

Coefficients of the wage equation are directly interpretable. For instance, the average wage in the Western region of the Netherland is 9.3 % higher than in the rest of the Netherlands.Footnote 35 Furthermore, we see that a higher education results in a higher wage. The relationship between wage and age is positive as well, but diminishing in age. The quadratic term dominates at an age of 52 and 80 for single men and women respectively. Finally, we find a negative relationship between wages and ethnicity.

It is important to note that the coefficients of the participation equation are not directly interpretable. The participation equation is estimated with a probit model, where the marginal effects are not constant and depend on the level of explanatory variables. In the participation equation, we see that most coefficients are significant as well. For single men, the coefficients for older children are not significant. This is probably due to the low number of observations of men with young children in the sample. Furthermore, cultural factors may also play an important role. For single women, coefficients for age of the youngest child have the expected sign: as the youngest child is older, the probability of participation increases. The relationship between the probability of participation and age (positive, but declining), ethnicity (negative) and region (positive) is as expected. The coefficient rho is less than 0, but not significant for single men. This means that we cannot reject the null hypothesis that unobserved characteristics are not negatively correlated. However, the coefficient rho is significant for single women at the 1 % level.

Table 10 shows the results for the wage and participation equation for couples, again estimated separately for men and women. Most of the coefficients for couples are significant and have the expected sign. In the wage estimation for couples we see that rho significantly differs from 0 for both men and women. Rho’s coefficient is positive which means that unobservable characteristics have a positive effect on both wages as well as participation.

Appendix 2: Descriptive Statistics

Appendix 3: Estimated Preferences

Appendix 4: Fit Hours Distribution

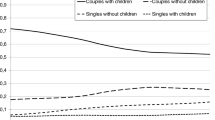

Figures 3 and 4 show the fit of the model for singles without children and single parents, respectively. Both figures show the actual and predicted labour supply distribution, where the labour supply options are located on the horizontal axis and the vertical axis indicates their shares (in %). Both figures show that the model predicts the labour supply distribution well. The same holds for couples (see Figs. 5a, b, 6a, b).

Appendix 5:Robustness Analysis

See Table 16.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

de Boer, H.W. For Better or for Worse: Tax Reform in the Netherlands. De Economist 164, 125–157 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-016-9272-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-016-9272-5