Abstract

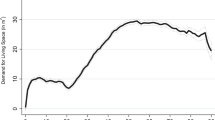

This study reexamines the price effects of age restrictions on housing prices. Our data cover a period when the housing market is taking a steep downturn. We argue that, when housing prices are falling, seniors are more likely to avoid investing in housing for at least two reasons. First, seniors are relatively more sensitive to their immediate equity loss than younger homeowners, mainly due to the limited remaining lifetime over which they can afford to wait; second, age-restriction acts as a luxury good, with seniors not willing to pay for reduction in neighborhood uncertainty, eliminating buyer demand for this segment of the population. If this “larger demand loss” outweighs the positive externality of the reduction in neighborhood uncertainty during the market downturn, we would observe that age-restrictions reduce property values. Using data from Broward County, Florida for the years of 2005–2007, we find a significant discount in residential condominium prices due to age-restrictions. In particular, we find that imposing age-restriction on properties decreases housing prices by 17.9% during the period May 2005 to April 2006, while the discount is worse, 22.7%, during the later period May 2006 to May 2007.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Downs (2009) pp. 54–56 points out that while housing indexes are normally accurate, during the turbulent times after 2005 the three indexes used for tracking national housing differed significantly from each other. These were the Case-Shiller Index, the National Association of Realtors© Index, and the Federal Housing Finance Agency Index. Differences were matters of degree and did not reflect housing markets generally rising or falling. Case-Shiller Housing Price Index can be downloaded at http://www.standardandpoors.com

To compute the discount, we use Equation (17). In addition, in order to mitigate the concern of any multicollinearity problem in our model, we use a common approach to calculate the variance inflation factor (VIF) by following Belsley, Kuh and Welsch (1980) and we find no multicollinearity issue in our regression models, see Appendix for details.

References

Allen, M. (1997). Measuring the effects of ‘adults only’ age restrictions on condominium prices. Journal of Real Estate Research, 14(3), 339–346.

Belsley, D., Kuh, E., & Welsch, R. (1980). Regression Diagnostics: Identifying Influential Data and Sources of Collinearity. New York: Wiley.

Cheng, P., Lin, Z., & Liu, Y. (2008). A model of time-on-market and real estate price under sequential search with recall. Real Estate Economics, 36, 813–843.

Do, Q., & Grudnitski, G. (1997). The impact on housing values of restrictions on rights of ownership: the case of an occupant’s age. Real Estate Economics, 25(4), 683–693.

Downs, A. (2009). Real estate and the financial crisis. Washington: ULI-Urban Land Institute.

Follain, J., & Malpezzi, S. (1981). Are occupants accurate appraisers? Review of Public Data Use, 9(1), 46–55.

Goodman, A., & Thibodeau, T. (1997). Dwelling-Age-Related Heteroskedasticity in Hedonic House Price Equations: An Extension. Journal of Housing Research, 8(2), 299–317.

Guntermann, K., & Moon, S. (2002). Age restrictions and property values. Journal of Real Estate Research, 24(3), 263–278.

Guntermann, K., & Thomas, G. (2004). Loss of age-restricted status and property values: Youngtown, Arizona. Journal of Real Estate Research, 26(3), 255–275.

Halverson, R., & Pollakowski, H. (1981). The interpretation of dummy variables in semilogrithmic regression. Journal of Urban Economics, 10(1), 37–49.

Hughes, W., & Turnbull, G. (1996a). Uncertain neighborhood effects and restrictive covenants. Journal of Urban Economics, 39, 160–172.

Hughes, W., & Turnbull, G. (1996b). Restrictive land covenants. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 12(9), 9–21.

Kennedy, P., (1984). Estimation with correctly interpreted dummy variables in semilogarithmic equations. American Economic Review, 801.

Krugman, P. (2009). The return of depression economics and the crisis of 2008. NY: W. W. Norton & Co.

Lancaster, K. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy, 74, 132–157.

Lin, Z., Liu, Y., & Yao, V. (2010). Ownership restrictions and housing value: evidence from an American housing survey. Journal of Real Estate Research, 32, 201–220.

Rosen, S. (1974). Hedonic prices and implicit markets. Journal of Political Economy, 82, 34–55.

Shiller, R. (2008). The subprime solution: how today’s global finance crisis happened, and what to do about it. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Spahr, R. W., Evans, R. D., and Sundermann, M. A. (2009). Mortgage ex post default pure risk premiums: The memphis experience,” paper given at the ARES 2009 meeting, Monterey, CA

Village of Belle Terre v. Boraas, 416 U.S. 1 (1974)

Zandi, M. (2009). Financial shock: A 360 o look at the subprime mortgage implosion, and how to avoid the next financial crisis. Upper Saddle River: FT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper is the winner of 2010 American Real Estate Society manuscript award for Seniors Housing.

Appendix

Appendix

When a regressor is nearly a linear combination of other regressors in the model, the estimates for a regression model may not be uniquely computed. This problem is called collinearity or multicollinearity. The primary concern is that as the degree of multicollinearity increases, the regression model estimates of the coefficients become unstable and the standard errors for the coefficients can be wildly inflated. There are many ways to detect multicollinearity. We use the most common approach to calculate the variance inflation factor (VIF) by following Belsley et al. (1980). Below is the summary of multicollinearity diagnostics:

Belsley et al. (1980) suggest that if the VIF is around 10 or less (or Tolerance is around 0.10 or higher), the multicollinearity issue should not be of a great concern. However, if the VIF is larger than 100 (or Tolerance is lower than 0.01), the estimates should have a fair amount of numerical error and the multicollinearity issue must be addressed. Since VIF numbers in our regression models are much less than 100 and around 10 or less, and the VIF number for agerest (the most important variable in our study) is only 1.16, we conclude that there is no multicollinearity issue in our regression models.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carter, C.C., Lin, Z., Allen, M.T. et al. Another Look at Effects of “Adults-Only” Age Restrictions on Housing Prices. J Real Estate Finan Econ 46, 115–130 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-011-9317-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-011-9317-0