Abstract

The available classifications of self-regulated learners may not be applicable to second or foreign language writing due to the contextual nature of self-regulated learning. This study intended to fill the gap by exploring the profiles of English as a foreign language (EFL) learners’ writing self-regulation and their association with writing-relevant individual differences. A total of 391 tertiary students from Southwest China were recruited to participate in the current study, including freshmen, sophomores, and juniors. Their writing self-regulation was measured by the Writing Strategies for Self-Regulated Learning Questionnaire. Latent profile analyses discovered two profiles of self-regulated learners in EFL writing: “highly self-regulated group” and “moderately self-regulated group”. Moreover, ANOVA and Welch’s Test showed that the participants assigned to the two profiles differed significantly in L2 grit, writing achievement goals, and writing self-efficacy rather than language aptitude and working memory. Perseverance of effort, mastery goals, and self-regulatory self-efficacy are found to predict profile membership significantly. Additionally, the results of path analyses revealed that the profiles varied in the predictive effect of individual differences on EFL learners’ writing regulation. These findings contributed to furthering our understanding of classification of self-regulated learners and the role of individual differences in the classification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acquiring second or foreign languages (hereafter referred to as L2) involves a series of cognitive, affective, and behavioural factors (e.g., Ellis, 2008). Learning to orchestrate these factors is highly indispensable for L2 learners’ mastery of the target languages (Zhang et al., 2019). Self-regulated learning (SRL) offers an insightful perspective on how L2 learners orchestrate these factors, especially so when we examine the learning of writing skills (Zhang, 2022). Accordingly, helping L2 learners achieve a high level of self-regulation is considered one of the primary objectives of L2 teaching and learning (Teng, 2020; Zhang & Zhang, 2019). Effective SRL processes require learners’ active deployment of a range of strategies to help them intentionally activate, sustain, and adjust cognition, affect, and behavior to achieve their learning goals (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2011).

A high level of self-regulation is required of writers in addition to vocabulary and grammar (Zimmerman & Risemberg, 1997). According to Zimmerman and Risemberg (1997), self-regulation of writing refers to writers’ “self-initiated thoughts, feelings, and actions to achieve various writing goals, including improving their writing skills and enhancing the quality of their text” (p. 76). Contextualizing Zimmerman’s conceptualization of SRL in L2 writing, Teng and Zhang (2016) proposed a multidimensional model of SRL writing strategies, including cognitive, metacognitive, social-behavioural, and motivational regulation strategies.

In the field of applied linguistics, the variable-centered approach has been the dominant research method, particularly in studying SRL in L2 learning. However, the person-centered approach is gaining popularity due to its ability to offer fine-tuned details. Guided by the person-centered approach, scholars utilized cluster analysis or latent profile analysis to detect profiles or subgroups of self-regulated learners in general (Karlen, 2016; Ning & Downing, 2015) and within specific contexts, such as teacher education students (Muwonge et al., 2020), academic writing (Csizér & Tankó, 2017), English as a foreign language (EFL) learning in general (Chen et al., 2020), EFL listening (Chon & Shin, 2019), EFL reading (Chen et al., 2023), and EFL writing (Chen et al., 2022). Chen et al. (2022) identified three latent profiles of self-regulated learners regarding EFL writing by integrating SRL strategy use and writing self-efficacy and transforming the original data. The discovery presented by Chen et al. (2022) provides only a restricted amount of insight into our comprehension of the profiles of writing self-regulation in EFL contexts. Moreover, it is common in existing research to classify self-regulated learners into three subgroups based on their varying degrees of self-regulation, namely, high, medium, and low. However, it should be noted that these classifications may not be applicable to EFL writing due to the contextual nature of self-regulated learning, as pointed out by Teng and Zhang (2018). Therefore, it is imperative that additional research be conducted to concentrate specifically on the identification of the latent profiles of EFL learners’ writing self-regulation.

Furthermore, while establishing SRL profiles is necessary, further research is required to determine the characteristics that can accurately predict an SRL profile’s membership. Although learning factors (such as instructional quality, measurable goals and standards, proper assessment, and workload) have been found to predict the SRL profiles’ membership significantly (Ning & Downing, 2015), additional factors need to be investigated to facilitate teachers in identifying subgroups of self-regulated learners in their classroom. Besides, identifying profiles of self-regulation in EFL writing might enable us to discover more details about the predictive effects of individual differences (e.g., grit, motivation, and self-efficacy) on EFL learners’ writing self-regulation.

To narrow down the lacuna in the literature, this study explored the profiles of EFL learners’ writing self-regulation and the association between the profiles and individual differences (specifically, the predictiveness of individual differences in the membership of the profiles and the differences across the profiles of the predictive effects of individual differences on writing self-regulation.)

Literature review

The role of self-regulation in writing

SRL was defined as “an active, constructive process whereby learners set goals for their learning and then attempt to monitor, regulate, and control their cognition, motivation, and behavior, guided and constrained by their goals and the contextual features in the environment” (Pintrich, 2000, p. 453). Thus, SRL is essential to learners’ perceptions and understanding of the orchestration of the cognitive, motivational, metacognitive, and behavioral aspects of learning.

Self-regulated learners were generally conceived as “metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally active participants in their own learning process” (Zimmerman, 1989, p.329). They might achieve their academic goals by means of proactively setting goals, utilizing effective strategies, monitoring their learning, and manipulating resources (Schunk, 2005).

Proponents of the social cognitive perspective conceived self-regulation as the interaction of personal, behavioral, and environmental processes (e.g., Bandura, 1986), including covert self-regulation, behavioral self-regulation, and environmental self-regulation. Covert self-regulation assumed that students monitor and adapt their cognitive and affective resources; behavioral regulation assumed that students proactively utilized strategies to monitor and evaluate their performance continuously and adjust their actions to enhance their learning; environmental regulation assumed that students actively employed strategies to manipulate environmental influences to benefit their learning (Zimmerman, 1989). These regulations were conceived to be connected through three interdependent strategic feedback loops to take effect synergistically. Zimmerman (2013) perceived that the cyclical dependence on the feedback resources to direct strategic adaptions acted as a vital characteristic of this triadic model of SRL. This model postulated the reciprocal causal relationships among person, environment, and behavior, as demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Effective SRL processes require learners’ active deployment of a range of strategies to help them intentionally activate, sustain, and adjust cognition, affect, and behavior to achieve their learning goals (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2011). The importance of SRL strategies was emphasized in the conceptualization of SRL given by Zimmerman (1989). SRL strategies refer to “actions and processes directed at acquiring information or skill that involve agency, purpose, and instrumentality perceptions by learners” (Zimmerman, 1989, p. 329).

Zimmerman and his colleagues initially applied the concept of SRL to L1 writing (Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994; Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 2002; Zimmerman & Risemberg, 1997). Zimmerman and Risemberg (1997) argued that high levels of regulation are essential to writing activities in addition to vocabulary and grammar in that writing is conceived as initiated, planned, and sustained by writers per se. Building on the triadic model of SRL, they proposed a social cognitive model of writing that involves three categories of self-regulation: environmental, behavioral, and covert or personal. It was presupposed that the reciprocal interactions of these self-regulations are realized through the cyclic feedback loop, where students monitor and react to the effectiveness and efficiency of their self-regulation.

Self-regulation, according to Graham and Harris (2000), facilitated writing performance in two fashions. To begin with, self-regulatory mechanisms writers employed to effectively complete writing tasks involved planning, monitoring, evaluating, and revising. In addition, these mechanisms served as a driver to induce strategic adjustments in writing processes and actions. Scholars identified a great number of SRL strategies that writers utilized to manipulate environmental, behavioral, and personal processes in their self-regulation of writing (Glaser & Brunstein, 2007; Graham & Harris, 2000; Zimmerman & Riesemberg, 1997). Self-regulated writers employed multiple SRL writing strategies through different stages of the writing process (Glaser & Brunstein, 2007). In the phase of planning, writers control the environmental setting, analyze writing task requirements, set their performance goals, and plan and generate their writing messages by employing SRL strategies such as goal setting and planning, seeking information, record keeping, environmental structuring, and time planning. During the process of translating, writers transcribed their writing messages into textual productions by utilizing SRL strategies like transforming, self-monitoring, reviewing records and self-verbalizing. At the stage of reviewing and revision, writers evaluated the produced texts using SRL strategies such as self-evaluating, revising, and rehearsing.

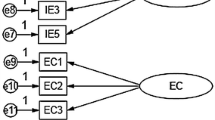

Building on Zimmerman’s conceptualization of SRL, Teng and Zhang (2016) proposed the multidimensional model of SRL writing strategies to address the role of cognitive, metacognitive, social-behavioral, and motivational processes, including four categories of strategies: cognitive, metacognitive, social-behavioral, and motivational regulation, as shown in Fig. 2. Cognitive strategies were defined as “skills students use to process the information or knowledge in completing a task” (Teng & Zhang, 2016, p. 8). Metacognitive strategies, in contrast, refer to “the skills used to control and regulate learners’ own cognition and the cognitive resources they can apply to meet the demands of particular tasks” (Teng & Zhang, 2016, p. 8). Social behavioral strategies entailed “individuals’ attempts to control their learning behavior under the influence of contextual and environmental aspects” (Teng & Zhang, 2016, p. 8), whereas motivational regulation strategies referred to “the procedure or thoughts that students apply purposefully to sustain or increase their willingness to engage in a task” (Teng & Zhang, 2016, p. 9). Teng and Zhang’s model allowed us to gain a more sophisticated understanding of SRL writing strategies (Teng & Huang, 2019), which consequently served as the guiding framework for this study.

Studies on profiling self-regulation in L2 learning

While the variable-centered approach is dominant in applied linguistics research, especially research on SRL in L2 learning, the person-centered approach is gaining popularity rapidly because of the fine-tuned details it might offer. The assumption behind the variable-centered approach is that for every member of a sample drawn from a given population, a set of parameters can be estimated based on average (Spurk et al., 2020). However, this assumption is loosened in the person-centered approach, where it could take into account the possibility of many subpopulations with their unique sets of parameters in a given population (Spurk et al., 2020).

Furthermore, the variable-centered approach is mainly employed to examine the relationship between variables of interest in a given population (e.g., the effect of one variable on another), whereas the purpose of the person-centered approach is to detect the emergent subpopulations in a given population according to a set of chosen variables (Bergman, 2001). When it comes to SRL, the variable-centered approach is used to investigate the antecedents (i.e., the predictive effects of variables such as self-efficacy on the employment of SRL strategies) and consequences (i.e., the effects of SRL strategies on learning outcomes) of SRL strategies or interrelationship between SRL strategies. For instance, Teng and Zhang (2016) examined the relationship between SRL writing strategies and writing achievement in a sample of Chinese-speaking EFL learners. Scholars explored the factors influencing L2 students’ employment of SRL writing strategies, for instance, proficiency (Bai et al., 2014), instruction (Bai, 2015), gender and grade level (Bai et al., 2020a), and writing self-efficacy, growth mindset, and task value (Chen & Zhang, 2019; Bai et al., 2020b).

In contrast, scholars utilized the person-centered approach to identify the potential subgroups of learners characterized by their similar utilization of SRL strategies. With the help of cluster analyses and latent profile analyses, scholars have found various groups of self-regulated learners based on the frequencies of strategies regulating their cognitive resources, metacognition, social behaviors, affect and motivation. Trichotomous subgroups, as characterized by high, medium, and low scores on all the subscales measuring different SRL strategies, are typical in the available studies on profiling self-regulated learners (e.g., Csizér & Tankó, 2017; Muwonge et al., 2020). The “High on All” subgroup was further partitioned into another two groups with different preferences towards certain strategies (e.g., Chon & Shin, 2019; Karlen, 2016; Ning & Downing, 2015), for example, metacognitive oriented subgroup and social-behavioral oriented one.

Csizér and Tankó (2017) examined English majors’ self-regulatory control strategy use in academic writing, which was measured by a self-developed questionnaire including environmental control, satiation control, metacognitive control, emotional control, and commitment control. Through cluster analyses, they found three subgroups: high control learners, characterized by high scores on all the subscales except the environmental control; average control learners, characterized by average scores on the subscales; and low control learners, characterized by low scores on the subscales. Ning and Downing (2015) investigated Hong Kong college students’ SRL strategies (i.e., cognitive, metacognitive, and behavioral strategies) by adopting the subscales from the Learning and Study Strategies Inventory (Weinstein & Palmer, 2002). Employing the latent profile analysis, they discovered four profiles: competent self-regulated learners featuring high endorsement for all SRL strategies (25.4% of the participants), cognitive-oriented self-regulated learners featuring high endorsement for cognitive and metacognitive strategies but low endorsement for behavioral strategies (20.4%), behavioral-oriented self-regulated learners featuring high endorsement for behavioral strategies, and minimal self-regulated learner featuring low endorsement for all SRL strategies. They also found that learning experience factors (i.e., teaching quality, clear goals and standards, appropriate assessment and workload) could significantly predict the membership of the aforementioned profiles. Karlen (2016) investigated Swiss secondary students’ clusters in terms of various SRL components (i.e., cognitive, metacognitive, and motivational). By means of the cluster analysis, he identified four clusters of self-regulated learners: unmotivated learners characterized by the lowest levels of all the aforementioned SRL components (7.6%), confident learners characterized by the relatively high level of motivation, self-concept, self-efficacy (25.3%), strategic learners characterized by high levels of metacognitive strategy knowledge and strategy use (26.3%), and maximal learners characterized by the highest levels of all the SRL components (40.8%).

Chen et al. (2020) examined Chinese tertiary EFL learners’ SRL strategies (i.e., cognitive, metacognitive, social, and affective strategies), which were measured by the Questionnaire of English Self-Regulated Learning Strategies. They identified three profiles: metacognitive learners characterized by the highest scores on all subscales (11.6%), cognitive learners characterized by scores relatively lower than metacognitive learners (48.3%), and memorization learners characterized by high scores on the subscales measuring behavioral regulation (11.6%). Chen et al. (2023) examined Chinese secondary students’ employment of SRL strategies (i.e., cognitive, metacognitive, and motivation regulation strategies) in EFL reading and spotted three profiles characterized by high, medium, and low levels of employing SRL strategies.

The studies reviewed above are based on different conceptions of SRL, most of which focus on different combinations of various categories of SRL strategies, for instance, cognitive + metecognitive + motivation regulation, cognitive + metacognitive + social behavior. No study has investigated how EFL students self-regulate their motivation, social behavior, metacognition, and cognition simultaneously from a person-centered approach. What is unique is that Karlen (2016) incorporated metacognitive strategy knowledge, motivation, and strategy use.

As argued in the above section, self-regulation is essential for student writers to become adept in L2 writing. It is imperative to identify subgroups of self-regulated learners in EFL writing in order to offer an elaborate understanding of the subgroups of EFL learners. Our literature search found that only Chen et al. (2022) explored the latent profiles of writing self-regulation among Chinese-speaking tertiary EFL learners. In their study, Chen et al. (2022) successfully discerned three distinct latent profiles among the learners through the integration of SRL strategy use and writing self-efficacy. The first group, referred to as efficacious self-regulators, demonstrated the highest level of SRL strategy use and strong belief in their own writing capabilities. The second group, known as moderate strategists, exhibited a moderate level of SRL strategy use and writing self-efficacy. The third group consisted of unmotivated learners who displayed the lowest level of SRL strategy use and lacked confidence in their writing skills. The findings presented here might offer a limited understanding of the latent profiles of self-regulation in EFL writing because they based their classification on the integration of the SRL strategy use and writing self-efficacy and the ensuing transformed data calculated via z-score. Additionally, the transformation of the original data might obscure the authentic status quo regarding EFL learners’ SRL strategy use and writing self-efficacy. These profiles regarding writing self-regulation in the EFL context need to be corroborated or verified by more experimental studies because SRL is conceived to be context- and skill-specific (Teng & Zhang, 2018). Hence, it is crucial to conduct further research that focuses specifically on identifying the latent profiles of writing self-regulation among EFL learners.

Although identifying SRL profiles is significant, it is necessary to go further to detect which factors can significantly predict the membership of the SRL profiles. Our literature search found that only Ning and Downing (2015) demonstrated that learning experience factors (i.e., teaching quality, clear goals and standards, appropriate assessment and workload) could significantly predict the membership of the SRL profiles. It is necessary to conduct more studies to explore other factors that might significantly predict the SRL profile membership, offering teachers a simpler and more convenient way to spot subgroups of self-regulated learners in their classrooms. Moreover, extant studies have revealed that SRL strategy use in L2 writing can be significantly predicted by the following factors: collaborative writing (Rahimi & Fathi, 2022), feedback engagement (Li & Zhang, 2023), grit and motivation (Guo et al., 2023), and self-efficacy (e.g., Teng, 2021). Given the fact that SRL is a skill-specific construct, it is imperative to examine the role of writing-relevant individual differences in predicting SRL strategy use in EFL writing. Based on the review of writing models and the difference between L1 and L2 writing, Zhang (2023) argued that the following individual differences are closely related to L2 writing: language aptitude, working memory, L2 grit, writing achievement goals, and writing self-efficacy. Identifying the profiles of self-regulated student writers might provide us with an opportunity to investigate the possible profile differences in the predictive effects of individual differences on EFL learners’ employment of SRL writing strategies, thus yielding more specific knowledge of the aforementioned predictive effects, which could facilitate teachers in tailoring their instructional practices to develop students’ SRL strategy use in L2 writing.

Method

To fill the aforementioned research lacuna, this study was designed to explore the profiles of EFL learners’ writing self-regulation and their possible relationships with writing-relevant individual difference variables. Based on Zimmerman and Risemberg’s (1997) conceptualization of writing self-regulation and Teng and Zhang’s (2016) model of SRL writing strategies, we operationalized writing self-regulation as SRL strategies or techniques students employ to regulate their cognitive, metacognitive, social-behavioral, and motivational processes. Specifically, this study addressed the following research questions:

RQ1 What are the latent profiles of EFL learners’ SRL writing strategy use?

RQ2 Are there profile differences in EFL learners’ SRL writing strategy use and writing-relevant individual differences?

RQ3 Which writing-relevant individual differences might predict the membership of the latent profiles of EFL learners’ SRL writing strategy use?

RQ4 Are there profile differences in the predictive effects of writing-relevant individual differences on EFL learners’ SRL writing strategy use?

Context and participants

Contextual factors like culture and education are crucial issues for SRL study due to their moulding effects on students’ development of self-regulation in their learning (Wang, 2018). Chinese students have been stereotyped as passive, examination-focused learners due to the impact of Confucian Heritage Culture and education. English learning and instruction at the universities and colleges in Chinese have been driven by its predominantly test-oriented education system. In keeping with the latest version of the College English Test Syllabus approved and published by China’s Ministry of Education in 2017, the writing module of CET4/6 (a nationwide English test for college and university students in China) accounts for 15%, while its listening and reading modules occupy 35%, respectively. Understandably, compared with reading and listening, writing is more or less a neglected skill (Zhang, 2016). Examining how EFL learners regulate their writing in this particular learning context might offer new insights into theorizing writing self-regulation and SRL in general.

With regard to the research objective, a total of 396 tertiary students from two universities in Mainland China who had learned English for at least six years and Mandarin Chinese as their first language were randomly recruited to participate voluntarily in this study through convenient sampling after signing formal consent. The participants were recruited with approval from department deans, where recruitment notices were sent to interested students by department secretaries. The participants consisted of 59.34% (n = 235) females and 40.66% (n = 161) males, with an age range of 18–22 and an average age of 20.4. They pursued various majors, including electronic engineering (n = 65, 16.41%), computer science (n = 68, 17.17%), education (n = 69, 17.42%), business (n = 108, 27.27%), and administration (n = 97, 24.49%), and were in different grade levels, with 49.49% (n = 196) being freshmen, 25.51% (n = 101) sophomores, and 25% (n = 99) juniors. Their English proficiency ranged from pre-intermediate to intermediate.

Power analysis was employed to determine the required sample size for the current study. A two tailed t-test was conducted with the help of G*Power 3.1.9.7, where effect size, α error probability, and power were set at 0.3, 0.05, and 0.95 respectively. The results of the t-test showed that noncentrality parameter δ, critical t, total sample size, and actual power were 3.640, 1.978, 134, and 0.951, respectively. The results may suggest that the sample size of the current study has met the requirements of the power analysis.

Instruments

LLAMA tests

The LLAMA tests, an online free-accessible language aptitude test battery (Meara & Rogers, 2019), were employed to measure the participants’ language aptitude. The psychometric qualities of the LLAMA tests have been proven robust (Rogers et al., 2017). The LLAMA tests are available for any researchers of interest for free at http://www.lognostics.co.uk/tools/LLAMA_3/index.htm. This battery was developed on the basis of the classic Modern Language Aptitude Test and has been conceived as a language-neutral test for language aptitude (Rogers et al., 2017) mainly because the symbols and sounds from a British-Columbian indigenous and a Central American language were adopted as the picture stimuli and verbal materials involved in these tests.

The LLAMA tests include four modules: The LLAMA Test_B for vocabulary acquisition, the LLAMA Test_D for sound recognition, the LLAMA Test_E for sound-symbol associations, and the LLAMA Test_F for grammatical inferencing. Two modules of the LLAMA tests, the LLAMA Test_B and the LLAMA Test_F, were employed to gauge the participants’ vocabulary learning ability and grammatical inferencing abilities. The user-friendly LLAMA tests can be taken online, as mentioned before, and the participants might take nearly 25 min to finish them.

The operation span task

The participants’ working memory capacity was measured employing the operation span (OSPAN) task, which was developed by Engle and his colleagues (e.g., Turner & Engle, 1989; Kane et al., 2001; Kane & Engle, 2003). The OSPAN task might require the participants to complete two categories of subtasks in order: They would be required to memorize the words or randomly combined letters after solving a series of integrated mathematical problems, including such operations as adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing. Choosing the OSPAN task in this study was partially because it has shown concurrent validity with other tests of working memory capacity (e.g., the reading span test) (Unsworth et al., 2005) and partially because it might prevent the confounding impact of the testees’ target language proficiency on measuring working memory capacity (e.g., Service et al., 2002; Van den Noort et al., 2006).

The Automated OSPAN task was adopted in this study, which was developed by Unsworth et al. (2005) as an online version of the original OSPAN task created by Engle and his colleagues, as mentioned before. The Automated OSPAN task was provided to the participants through Inquisit Lab 6 (i.e., a mobile application), through which the participants could access the task and complete it on their smartphones conveniently without the trouble of logging into their computers. The task entailed both a mock trial and an actual trial. The mock trial included three parts: memorizing the letters, calculating the mathematical operation, and the combination of the former two. The mock trial would help the participants to get familiar with the test items involved in the task and the ways of performing the task. After completing the mock trial, participants were required to finish the actual trial which might include three sets of test items. The set size varied from 3 to 7. There is a time limit set for participants to solve the math problem; otherwise, the test might continue on its own, and the participants’ performance could be considered unsuccessful. The OSPAN score, representing the total of sets that the participants could recall correctly, was employed to show participants’ working memory capacity.

L2 student writer survey

The L2 Student Writer Survey included a short background questionnaire and another four scales measuring the participants’ L2 grit, writing achievement goals, writing self-efficacy, and SRL writing strategies, respectively: L2 Grit Scale (Teimouri et al., 2020), the Writing Achievement Goals Scale (Yilmaz Soylu et al., 2017), the Genre-Based L2 Writing Self-Efficacy Scale (Zhang et al., 2023), and the Writing Strategies For Self-Regulated Learning Questionnaire (Teng & Zhang, 2016). The background questionnaire was designed to elicit the participants’ demographic information, such as gender, age, major, grade, and English learning experience. The details of the aforementioned scales are discussed in the following part.

The grit scale

It was used to measure the participants’ L2 grit (i.e., learners’ tenacity and enthusiasm for L2 learning) through scrutinizing the personality traits and behavioural characteristics that they could exhibit in the process of learning the targeted L2. In contrast to the scales evaluating domain-general grit, L2 Grit Scale was designed as domain-specific (i.e., L2 learning), which might require the participants to respond on a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 indicating not like me at all and 5 indicating very much like me). Teimouri et al. (2020) demonstrated that the L2 Grit Scale displayed sound psychometric quality against L1-Persian EFL learners who had achieved various English proficiency. The items of the scale were directly adopted in this study to measure the participants’ L2 grit because this scale had been validated in the EFL context, which might be similar to the target EFL context in China. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was employed to assess the reliability of two subscales and the overall scale. The alpha coefficients demonstrated the sound internal consistency of the subscales (i.e., α = 0.81 for perseverance of effort and α = 0.679 for consistency of interest) and the overall scale (α = 0.724).

The writing achievement goals scale

It was employed to evaluate the participants’ motivations for writing, the goals students might set for writing essays. To be specific, the scale evaluated the participants’ three interrelated but different writing achievement goals: mastery goals, performance-approach goals, and performance-avoidance goals. The scale would require the participants to report their perceived motivations on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (does not describe me) to 5 (describes me perfectly). Yilmaz Soylu et al. (2017) revealed the scale displayed high reliability and validity against L1-English secondary students. Similarly, the reliability of this scale and its three subscales was also evaluated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, which suggest the sound internal consistency of this scale (α = 0.844) and its three subscales (α = 0.809 for mastery goal, α = 0.802 for performance-approach goals, and α = 0.856 for performance-avoidance goals).

The genre-based L2 writing self-efficacy scale

It was developed to assess L2 learners’ writing self-efficacy (i.e., their self-perceived confidence in completing the L2 writing tasks). Four dimensions of writing self-efficacy were incorporated and evaluated in the scale: linguistic self-efficacy, self-regulatory self-efficacy, classroom performance self-efficacy, and genre-based performance self-efficacy. The scale would ask the participants to rate their perceived confidence on a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 indicating does not describe me, and 5 indicating describes me perfectly. The psychometric quality of the scale was evaluated by Zhang et al. (2023), which revealed high reliability and validity against Chinese-speaking EFL tertiary students. In the same vein, the reliability of the scale and its four subscales against the specific sample group involved in this study was evaluated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, indicating the sound internal consistency of the overall scale (α = 0.92) and its four subscales (α = 0.849 for linguistic self-efficacy, α = 0.811 for self-regulatory self-efficacy, α = 0.882 for classroom performance self-efficacy, and α = 0.873 for genre-based performance self-efficacy).

The writing strategies for self-regulated learning questionnaire

It was designed to evaluate L2 students’ perceived use of SRL writing strategies. Specifically, the scale assesses the following strategies: cognitive strategies (i.e., text processing and knowledge rehearsal), metacognitive strategies (i.e., goal-oriented monitoring and evaluation and idea planning), social-behavioural strategies (i.e., peer learning and feedback handling), and motivational regulation (i.e., interest enhancement, motivational self-talk, and emotional control). The questionnaire would ask participants to score their perceived use of SRL writing strategies on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating not at all true of me and 7 indicating very much true of me.

Teng and Zhang (2016) revealed that the scale displayed high reliability and validity with Chinese-L1 EFL learners at universities and colleges. Similarly, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was employed to evaluate the reliability of this scale and its subscales, whose values showed the acceptable internal consistency of the overall scale (a = 0.952) and its subscales (α = 0.821 for text processing, α = 0.761 for knowledge rehearsal, α = 0.834 for goal-oriented monitoring and evaluation, α = 0.702 for peer learning, α = 0.849 for feedback handling, α = 0.848 for interest enhancement, α = 0.904 for motivational self-talk, α = 0.799 for emotional control) except the subscale for idea planning (α = 0.574).

The items of the survey were provided to the participants in Mandarin Chinese so that they could completely comprehend them, thus reducing the possibility of misunderstanding. The wording of these items was examined and modified to fit the intended context.

Procedures

Because of the constraints of COVID-19 and the ensuing lockdowns, we had to collect the data through online interfaces. During the data collection, two sessions were involved: completing the LLAMA tests and the Automated OSPAN task and responding to the L2 Student Writers’ Survey. As mentioned before, the LLAMA tests were utilized to examine the participants’ language aptitude; the Automated OSPAN task was to assess the participants’ working memory, the L2 Student Writers’ Survey was to assemble the information about their demographics and also about their perceived personality trait (i.e., L2 grit), writing motivation (i.e., writing achievement goals) and self-efficacy belief (i.e., writing self-efficacy) and employment of SRL writing strategies. Clear instructions were offered to the participants on the procedures of performing the aforementioned tests and responding to the survey and the matters that needed to attend to. These instructions were reviewed and clarified before the participants started to perform the tests and provide their answers to the survey. Due to the impact of COVID-19, we asked all the participants to finish the aforementioned tests and survey online to avoid unnecessary personal contact and protect them from the troubles of COVID-19. The principle of anonymity was followed throughout the data collection and the following periods to safeguard the participants’ privacy. In the meantime, they were made aware of the following points: They have all the rights to quit at any session of the data collection and to withdraw their data after the data collection; there were no answers prescribed for the survey items; their decisions on whether to participate in this study or not might not exert any influence on their grades and interpersonal relationships with their instructors.

Data analysis

Following the recommendations offered by Dörnyei and Taguchi (2010), we performed the data screening and cleaning before conducting any further statistical analyses on the gathered data. The responses produced by five participants were eliminated from the dataset because they provided self-contradictory answers. Besides, the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v.24 was utilized to check and spot the missing data. Therefore, a total of 391 participants were retained for the final statistical analyses.

With the help of Mplus 8.3 (Muthen & Muthen, 2017), latent profile analyses were conducted to determine profiles of EFL students’ SRL writing strategy use. The maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was employed to compute the parameters of various latent profile solutions ranging from 1 profile to 5 profiles. Moreover, following the recommendations given by Jung and Wickrama (2008), we employed the following fitness indices to identify the profile that fitted well with the collected data: log-likelihood, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayes Information Criterion (BIC), the adjusted Bayes Information Criterion (aBIC), and entropy. Additionally, we also utilized the Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT) and bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT) to discover whether the differences between k and k-1 profiles are significant or not. The final latent profile was selected on the basis of considering the following estimations: higher entropy, lower AIC, BIC, and aBIC, the significant p values for LMR and BLRT, and the percentage of the members of the profiles.

Furthermore, the differences across the final profiles of EFL learners’ SRL writing strategy use were examined by the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and/or Welch’s Test, and the corresponding effect sizes were calculated. The same statistical analyses were employed to detect the difference across these profiles in terms of writing-relevant individual difference variables (i.e., language aptitude, working memory, L2 grit, writing achievement goals, and writing self-efficacy). Before conducting ANOVA and Welch’s Test, we performed Levene’s Test to examine the equality of variances of the variables involved for the identified profiles. Moreover, binary logistic regression was utilized to investigate whether these aforementioned individual differences variables and demographic data (i.e., gender, major, and grade) could predict the membership of the final profiles of EFL learners’ SRL writing strategy use. In addition, path analyses were employed to detect the differences across the final profiles in the predictive effects of these aforementioned individual difference variables on EFL learners’ use of SRL writing strategies. Following Kline’s (2016) suggestions, the fitness of the path models was assessed by the following indices: the χ2 test statistic with its level of significance, the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR).

Results

Profiles of EFL learners’ SRL writing strategy use

The exploratory latent profile analysis was employed to scrutinize the profiles of EFL students’ SRL writing strategy use. As mentioned previously, five possible solutions, including one- to five-profile, were checked. In addition, the conceptual differences within the final profile were examined to see whether they were distinguishable in terms of specific SRL writing strategies. The results of the five solutions mentioned are displayed in Table 1.

The statistics in Table 1 indicate that the proposed five-profile solution was not specified. In contrast to the two-profile solution with a significant p-value for LMR (pprofile−2=0.0136), the p-values for the three-profile and four-profile solutions were insignificant (pprofile−3=0.3553, pprofile−4=0.0679). These results might indicate there is a statistically significant difference between one-profile and two-profile solutions rather than between two-profile and three-profile solutions and also between three-profile and four-profile solutions. Furthermore, although the entropy of the four-profile solution was greater than those of the two-profile and three-profile solutions (entropy profile−4=0.873 > entropy profile−2=0.859 > entropy profile−3=0.853), the percentage of the member of a profile in the four-profile solution was lower than the critical value of 5%. Besides, the differences between one-profile and two-profile solutions in terms of AIC, BIC and aBIC were greater than those between two-profile and three-profile solutions and between three-profile and four-profile solutions. This result might suggest that the two-profile solution could be critical. Based on the above discussion, we could conclude that the two-profile solution fitted the assembled data well rather than the other solutions. The details of the two-profile solution are presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3 demonstrates that Profile 1 was characterized by the medium scores on EFL learners’ perceived use of four SRL writing strategies: cognitive strategies, metacognitive strategies, social-behavioral strategies, and motivational regulation strategies, while Profile 2 was typified by the high scores on EFL learners’ perceived use of all the aforementioned strategies. We labelled Profiles 1 to 2 as “moderately self-regulated group“(MSRG) and " highly self-regulated group (HSRG)”, respectively.

Moreover, ANOVA and Welch’s Test were employed to uncover whether there are statistically significant differences between MSRG and HSRG in terms of all the SRL writing strategies mentioned above. The statistics in Table 2 demonstrated significant differences between MSRG and HSRG in terms of text processing (F = 167.426, p < .001, η2 = 0.333), knowledge rehearsal (F = 165.903, p < .001, η2 = 0.299), goal-oriented monitoring and evaluation (F = 281.337, p < .001, η2 = 0.441), idea planning (F = 204.799, p < .001, η2 = 0.345), peer learning (F = 81.129, p < .001, η2 = 0.18), feedback handling (F = 90.71, p < .001, η2 = 0.231), interest enhancement (F = 206.643, p < .001, η2 = 0.378), motivational self-talk (F = 260.68, p < .001, η2 = 0.446), and emotional control (F = 210.074, p < .001, η2 = 0.384).

Besides, the membership of the final two profiles was displayed as follows: One hundred thirty-nine participants were assigned to MSRG, comprising 35.55% of the total sample involved in this study, whereas two hundred fifty-two participants were assigned to HSRG, comprising 64.45%, as demonstrated in Table 1.

Profile differences in writing-relevant individual difference variables

In the same vein, ANOVA and Welch’s Test were conducted to discover EFL learners’ differences in language aptitude, working memory, writing achievement goals, L2 grit, and writing self-efficacy across the identified latent profiles of writing self-regulation, the results of which are shown in Table 2.

According to the results of ANOVA and Welch’s Test in Table 2, MSRG and HSRG were significantly different in the following individual differences: mastery goals (F = 110.358, p < .001, η2 = 0.249), performance-approach goals (F = 45.172, p < .001, η2 = 0.104), perseverance of effort (F = 100.353, p < .001, η2 = 0.205), consistency of interest (F = 4.398, p < .005, η2 = 0.01), and linguistic self-efficacy (F = 68.703, p < .001, η2 = 0.15), self-regulatory self-efficacy (F = 130.27, p < .001, η2 = 0.251), classroom-based performance self-efficacy (F = 39.81, p < .001, η2 = 0.093), and genre-based performance self-efficacy (F = 46.047, p < .001, η2 = 0.106). In contrast, MSRG and HSRG were not significantly different in components of language aptitude, working memory, and performance-avoidance goals.

Predicting profile memberships of EFL learners’ SRL writing strategy use

The binary logistic regression was utilized to investigate whether writing relevant individual difference variables and demographic information could predict the membership of the final profile of EFL learners’ self-regulation, whose results are presented in Table 3.

As Table 3 shows, mastery goal (estimate = 3.027, p < .001), perseverance of effort (estimate = 1.2, p = .013), and self-regulatory self-efficacy (estimate = 3.027, p < .001) could significantly predict the membership of the final profile of EFL writing self-regulation rather than other factors of writing achievement goals, L2 grit and writing self-efficacy, language aptitude, working memory, and demographic data such as gender, major and grade. The predictiveness of mastery goals, perseverance of effort, and self-regulatory self-efficacy are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4 demonstrates that the participants who possess a higher level of mastery goal, perseverance of effort, and self-regulatory self-efficacy are more likely assigned to HSRG, whereas those possessing a lower level of mastery goal, perseverance of effort, and self-regulatory self-efficacy are more probably assigned to MSRG.

Profile differences in predicting EFL learners’ writing SRL writing strategy use

Path analyses were conducted to examine the profile differences in the predictive effects of writing-relevant individual difference variables on EFL Learners’ writing self-regulation. The constructed path model is justly identified (χ2 = 0, df = 0, CFI = 1, TLI = 1, RMSEA = 0, SRMR = 0, AIC = 7865.345, BIC = 9151.206). The results of the path analyses are displayed in Table 4.

The statistics in Table 4 reveal the following predictive effects for the MSRG: Participants’ use of text processing could be positively predicted by their linguistic self-efficacy (β = 0.236, p = .013); their use of knowledge rehearsal could be positively predicted by their mastery goal(β = 0.261, p = .011); their use of goal-orientated monitoring and evaluation could be positively predicted by their perseverance of effort (β = 0.326, p < .001); their use of peer learning could be positively predicted by their mastery goal (β = 0.199, p = .039) and performance-avoidance goal (β = 0.247, p = .006); their use of feedback handling could be positively predicted by their mastery goal (β = 0.258, p = .001) and performance-approach goal (β=-0.394, p < .001), their use of interest enhancement could be positively predicted by their mastery goal (β = 0.297, p = .004); their use of motivational self-talk could be predicted by their vocabulary learning ability (β = 0.224, p = .006), mastery goal (β = 0.352, p < .001), and self-regulatory self-efficacy (β = 0.373, p < .001); their use of emotional control could be positively predicted by their mastery goal (β = 0.381, p < .001), self-regulatory self-efficacy (β = 0.289, p = .002), and negatively by their genre-based performance self-efficacy (β=-0.311, p = .004).

In contrast, Table 4 discovers the following predictive impacts for the HSRG: their employment of text processing could be predicted by their consistency of interest (β = 0.1, p = .028), mastery goal (β = 0.288, p = .002), performance-avoidance goal (β = 0.168, p = .015), and self-regulatory self-efficacy (β = 0.177, p = .021); their employment of knowledge rehearsal could be predicted by their perseverance of effort (β = 0.229, p = .001); their employment of goal-oriented monitoring and evaluation could be predicted by their perseverance of effort (β = 0.242, p < .001) and performance-avoidance goal (β = 0.205, p = .003); their employment of idea planning could be predicted by their perseverance of effort (β = 0.215, p = .001) and master goal (β = 0.201, p = .041); their employment of peer learning could be predicted by their classroom performance self-efficacy (β = 0.2, p = .013); their employment of feedback handling could be predicted by their vocabulary learning ability (β = 0.107, p = .031), grammatical inferencing ability (β=-0.175, p = .002), consistency of interest (β = 0.118, p = .037), and mastery goal (β = 0.51, p < .001); their employment of interest enhancement could be predicted by their linguistic self-efficacy (β=-0.213, p = .002) and self-regulatory self-efficacy (β = 0.464, p < .001); their employment of motivational self-talk could be predicted by their perseverance of effort (β = 0.14, p = .019), mastery goal (β = 0.41, p < .001), self-regulatory self-efficacy (β = 0.163, p = .043), and classroom performance self-efficacy (β=-0.214, p = .002), their employment of emotional control could be predicted by their mastery goal (β = 0.368, p < .001) and self-regulatory self-efficacy(β = 0.189, p = .003).

Discussion

Profiles of EFL learners’ SRL strategy use and their membership

The first research question is intended to explore the profiles of SRL strategy use in EFL writing. The results of the latent profile analysis revealed that two profiles of self-regulated learners in relation to SRL writing strategy use surfaced from the samples of Chinese-speaking tertiary EFL learners: MSRG and HSRG. This finding is in contrast to the results presented by Csizér and Tankó (2017) and Chen et al. (2022). While Csizér and Tankó (2017) found three profiles of self-regulated learners among English majors: high-control learners, average control learners, and low-control learners, Chen et al. (2022) also identified three profiles of self-regulated learners in EFL writing: efficacious self-regulators, moderate self-regulators, and unmotivated learners. Csizér and Tankó (2017) adopted different operationalizations of self-regulation in their study from those in the current study. Csizér and Tankó (2017) operationalized self-regulation as “control over students’ thoughts, behaviors, learning environment, and motivation” (p. 388) and included environmental control, satiation control, metacognitive control, emotional control and commitment control in their measurements. On the contrary, self-regulation was operationalized in the current study as strategies or techniques students employ to regulate their cognitive, metacognitive, social-behavioral, and motivational processes and thus included four categories of SRL strategies: cognitive, metacognitive, social-behavioral, and motivational regulation. Although Chen et al. (2022) adopted the same conceptualization of self-regulation as in the current study, they conducted the classification by incorporating both SRL writing strategies and writing self-efficacy and employing the z-transformed data. Moreover, Csizér and Tankó (2017) utilized cluster analysis to estimate the subgroups of self-regulated learners, whereas latent profile analysis was employed in the current study. Compared with cluster analysis that estimated the cluster with some arbitrarily chosen distance measures, latent profile analysis may derive profiles based on a probabilistic model that depicts how the collected data is distributed (Spurk et al., 2020). Therefore, latent profile analysis might offer robust and trustworthy results concerning the subgroups of self-regulated learners in EFL writing, thus contributing to our elaborate understanding of the heterogeneity of EFL students in SRL writing strategy use. Besides, the finding of two profiles of SRL strategy use in EFL writing provided a shred of further evidence for the strategy chain proposed by Oxford (2003) that referred to a collection of strategies that are interdependent, interconnected, and mutually reinforcing.

The second research question aimed to detect the possible differences across the identified profiles of SRL writing strategies in relation to writing-relevant individual differences (i.e., language aptitude, working memory, writing achievement goals, L2 grit, and writing self-efficacy). The current study demonstrated significant variations across the identified profiles in terms of writing achievement goals (i.e., mastery goals and performance-approach goals), L2 grit, and writing self-efficacy rather than language aptitude, working memory and performance-avoidance goals. EFL learners assigned to HSRG reported higher levels of master goals, performance-approach goals, perseverance of effort, consistency of interest, linguistic self-efficacy, self-regulatory self-efficacy, classroom-based performance self-efficacy, and genre-based performance self-efficacy than those assigned to MSRG. These results might indicate that learners with similar cognitive abilities (i.e., language aptitude and working memory) could develop SRL strategy use differently in EFL writing, thus suggesting the malleability of writing self-regulation among L2/EFL students.

The current study showed that more than half of the participants were assigned to HSRG, whereas the rest were assigned to MSRG, suggesting the uneven development of SRL writing strategy use in EFL writing. This result provided more evidence to support the inappropriate distribution of learners across the profiles of self-regulation shown in the literature review (e.g., Chen et al., 2020; Csizér & Tankó, 2017; Muwonge et al., 2020; Ning & Downing, 2015).

The third research question is concerned with whether writing-relevant individual differences and demographic data can predict the membership of the identified profiles of SRL strategy use in EFL writing. The results of binary logistic analyses revealed that mastery goals, perseverance of effort, and self-regulatory self-efficacy exerted significant predictive impacts on the membership of the aforementioned profiles. This finding might suggest other variables than teaching quality, clear goals and standards, appropriate assessment and workload found in Ning and Downing’s (2015) could significantly predict the profile membership of SRL strategy use. Furthermore, this finding also could offer nuanced details on the kind of the goals that might exert predictive effects on the profile membership of SRL strategy use.

Profile differences in predictive effects of individual differences on EFL learners’ SRL strategy use

The fourth research question examined whether there are profile differences in the predictive impacts of individual differences on EFL learners’ SRL strategy use. Path analyses revealed evident differences between MSRG and HSRG in terms of the predictive effects of individual differences on EFL learners’ strategy use. For instance, MSRG’s use of text processing can be significantly predicted by their linguistic self-efficacy, whereas HSRG’s use of text processing can be significantly predicted by their consistency of interest, mastery goals, performance-avoidance goals, and self-regulatory self-efficacy. Moreover, MSRG’s endorsement for knowledge rehearsal can be foreseen by their mastery goals, while HSRG ‘s endorsement can be foreseen by their perseverance of effort. These results might provide partial evidence to support the predictive impacts of self-efficacy (Teng, 2021), grit, and motivation (Guo et al., 2023) on SRL strategy use in L2 writing, as demonstrated in the literature review.

The discovery that there are profile variations in the predictive impact of individual differences on the employment of SRL strategies by EFL learners could furnish a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that can forecast the use of SRL strategies in EFL writing by offering additional specifics. For instance, EFL learners’ linguistic self-efficacy can significantly predict their utilization of text processing only in MSRG, whereas their linguistic self-efficacy can have a significant predictive influence on their employment of interest enhancement only in HSRG. In contrast, the current study also revealed EFL learners’ self-regulatory self-efficacy could foretell their use of motivational self-talk and emotional control in both MSRG and HSRG. The differences and commonalities in the predictive impacts of writing self-efficacy were shared by L2 grit and writing achievement goals. Therefore, these results might help us to gain a more detailed understanding of the predictive effects of self-efficacy, L2 grit, and achievement goals on SRL strategy use in EFL writing.

What is unique in the current study is the finding that only EFL learners’ vocabulary learning ability exerted a significant predictive effect on their use of motivational self-talk in MSRG, while their vocabulary learning ability and grammatical inferencing ability exerted a significant predictive effect on their use of feedback handling in HSRG. This finding might contribute to our understanding of the predictive influence of language aptitude on SRL strategy use in EFL writing.

Conclusion

The current study explored profiles of EFL learners’ writing self-regulation and their associations with writing-relevant individual differences. The results of latent profile analyses revealed two profiles of SRL strategy use among EFL learners in the current study: MSRG and HSRG. Moreover, ANOVA and Welch’s Test showed that EFL learners assigned to these two profiles significantly differed in their SRL writing strategies, writing achievement goals, L2 grit, and writing self-efficacy rather than in language aptitude, working memory, and performance-avoidance goals. Additionally, path analyses unveiled profile differences and commonalities in the predictive influence of writing-relevant individual differences on SRL strategy use in EFL writing. Besides, the predictiveness of components of language aptitude on specific SRL strategy employment may vary across the identified two profiles.

A few implications might emerge from the findings for L2 writing research and pedagogical practices. Identifying the profiles of SRL strategy use in EFL writing may inform teachers of the specifics of EFL students’ writing self-regulation. Furthermore, the findings of the predictive effects of mastery goals, perseverance of effort, and self-regulatory self-efficacy on the profile membership might offer instructors simpler and more convenient ways to recognize which type of self-regulated learners particular EFL learners are. Moreover, the finding of profile differences in the predictive impacts of individual differences on EFL learners’ SRL strategy use might warn instructors of the inappropriateness of utilizing uniform teaching procedures to enhance learners’ endorsement of SRL strategies in their EFL writing. Therefore, it might be beneficial for teachers to adopt profile-specific techniques and methods to boost EFL learners’ employment of SRL strategies. For instance, to increase the SRL strategy of text processing, teachers should help students in the MSRG strengthen their linguistic self-efficacy, while teachers could adopt the following techniques for those in HSRG: Increase their interest in L2 learning, set appropriate achievement goals (i.e., high mastery goals and performance-avoidance goals), and improve their self-regulatory self-efficacy.

Admittedly, some limitations might deserve attention. Firstly, it should be noted that the current study mainly involved tertiary EFL learners with intermediate English proficiency as participants rather than those tertiary EFL learners with advanced English proficiency. As a result, the findings of the current study cannot be generalized to those with advanced English proficiency. Thus, it is recommended that scholars entail those with advanced English proficiency in future studies to validate the findings of the present study. Secondly, the current study included a limited set of individual differences to predict the profile membership and EFL learners’ SRL strategy use in their EFL writing and thus could not capture the complete picture of writing self-regulation. Accordingly, it might be advised that scholars include more individual differences (e.g., cognitive style and personality) to test their predictive effects on the membership of the profiles of writing self-regulation and also on SRL strategy use.

References

Bai, B. (2015). The effects of strategy-based writing instruction in Singapore primary schools. System, 53, 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2015.05.009.

Bai, B., Shen, B., & Mei, H. (2020a). Hong Kong primary students’ self-regulated writing strategy use: Influences of gender, writing proficiency, and grade level. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 65, 100839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100839.

Bai, B., Wang, J., & Nie, Y. (2020b). Self-efficacy, task values and growth mindset: What has the most predictive power for primary school students’ self-regulated learning in English writing and writing competence in an Asian confucian cultural context? Cambridge Journal of Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2020.1778639.

Bai, R., Hu, G., & Gu, P. Y. (2014). The relationship between use of writing strategies and English proficiency in Singapore primary schools. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23(3), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0110-0.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall series in social learning theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bergman, L. R. (2001). A person approach in research on adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16(1), 28–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558401161004.

Chen, J., Lin, C. H., Chen, G., & Fu, H. (2023). Individual differences in self-regulated learning profiles of Chinese EFL readers: A sequential explanatory mixed-methods study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263122000584.

Chen, J., & Zhang, L. J. (2019). Assessing student-writers’ self-efficacy beliefs about text revision in EFL writing. Assessing Writing, 40, 27–41.

Chen, J., Zhang, L. J., & Chen, X. (2022). L2 learners’ self-regulated learning strategies and self-efficacy for writing achievement: A latent profile analysis. Language Teaching Research, 136216882211349. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221134967

Chen, X., Wang, C., & Kim, D. H. (2020). Self-regulated learning strategy profiles among English as a foreign language learners. TESOL Quarterly, 54(1), 234–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.540.

Chon, Y. V., & Shin, T. (2019). Profile of second language learners’ metacognitive awareness and academic motivation for successful listening: A latent class analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 70, 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.01.007.

Csizér, K., & Tankó, G. (2017). English majors’ self-regulatory control strategy use in academic writing and its relation to L2 motivation. Applied Linguistics, 38(3), 386–404. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amv033.

Dörnyei, Z., and Taguchi, T. (2010). Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Ellis, R. (2008). The study of second language acquisition (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Glaser, C., & Brunstein, J. C. (2007). Improving fourth-grade students’ composition skills: Effects of strategy instruction and self-regulation procedures. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.297.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2000). The role of self-regulation and transcription skills in writing and writing development. Educational Psychologist, 35(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3501_2.

Guo, W., Bai, B., Zang, F., & Wang, T. (2023). Influences of motivation and grit on students’ self-regulated learning and English learning achievement: A comparison between male and female students. System, 103018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.103018.

Jung, T., & Wickrama, K. A. S. (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x.

Kane, M. J., Bleckley, M. K., Conway, A. R., & Engle, R. W. (2001). A controlled-attention view of working-memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 130(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.130.2.169.

Kane, M. J., & Engle, R. W. (2003). Working-memory capacity and the control of attention: The contributions of goal neglect, response competition, and task set to Stroop interference. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 132(1), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.132.1.47.

Karlen, Y. (2016). Differences in students’ metacognitive strategy knowledge, motivation, and strategy use: A typology of self-regulated learners. The Journal of Educational Research, 109(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.942895.

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (Fourth edition). Methodology in the social sciences. The Guilford Press.

Meara, P., & Rogers, V. (2019). The LLAMA tests V3. Lognostics.

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. (2017). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables, user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén. (Eighth edition).

Muwonge, C. M., Ssenyonga, J., Kibedi, H., & Schiefele, U. (2020). Use of self-regulated learning strategies among teacher education students: A latent profile analysis. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2(1), 100037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100037.

Ning, H. K., & Downing, K. (2015). A latent profile analysis of university students’ self-regulated learning strategies. Studies in Higher Education, 40(7), 1328–1346. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.880832.

Oxford, R. L. (2003). Language learning styles and strategies: An overview. GALA.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 451–502). Academic.

Rahimi, M., & Fathi, J. (2022). Exploring the impact of wiki-mediated collaborative writing on EFL students’ writing performance, writing self-regulation, and writing self-efficacy: A mixed methods study. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(9), 2627–2674. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1888753.

Rogers, V., Meara, P., Barnett-Legh, T., Curry, C., & Davie, E. (2017). Examining the LLAMA aptitude tests. Journal of the European Second Language Association, 1(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.22599/jesla.24.

Schunk, D. H. (2005). Self-regulated learning: The educational legacy of Paul R. Pintrich. Educational Psychologist, 40(2), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4002_3.

Service, E., Simola, M., Metsänheimo, O., & Maury, S. (2002). Bilingual working memory span is affected by language skill. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 14(3), 383–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/09541440143000140.

Spurk, D., Hirschi, A., Wang, M., Valero, D., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). Latent profile analysis: A review and how to guide of its application within vocational behavior research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120, 103445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103445.

Teimouri, Y., Plonsky, L., & Tabandeh, F. (2020). L2 grit: Passion and perseverance for second-language learning. Language Teaching Research, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820921895.

Teng, F. M., & Huang, J. (2019). Predictive effects of writing strategies for self-regulated learning on secondary school learners’ EFL writing proficiency. TESOL Quarterly, 53(1), 232–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.462.

Teng, L. S. (2021). Individual differences in self-regulated learning: Exploring the nexus of motivational beliefs, self-efficacy, and SRL strategies in EFL writing. Language Teaching Research, 136216882110068. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211006881.

Teng, L. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2016). A questionnaire-based validation of multidimensional models of self-regulated learning strategies. The Modern Language Journal, 100(3), 674–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12339.

Teng, L. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2018). Effects of motivational regulation strategies on writing performance: a mediation model of self-regulated learning of writing in English as a second/foreign language. Metacognition and Learning, 13(2), 213–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-017-9171-4

Teng, L. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2020). Empowering learners in the second/foreign language classroom: Can self-regulated learning strategies-based writing instruction make a difference? Journal of Second Language Writing, 48, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2019.100701.

Turner, M. L., & Engle, R. W. (1989). Is working memory capacity task dependent? Journal of Memory and Language, 28(2), 127–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-596X(89)90040-5.

Unsworth, N., Heitz, R. P., Schrock, J. C., & Engle, R. W. (2005). An automated version of the operation span task. Behavior Research Methods, 37(3), 498–505. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192720.

van den Noort, M. W., Bosch, P., & Hugdahl, K. (2006). Foreign language proficiency and working memory capacity. European Psychologist, 11(4), 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.11.4.289.

Wang, X. (2018). A study of Chinese junior secondary school students’ self-regulated learning, motivation, and English reading achievement [Doctoral Thesis]. The University of Auckland. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/46374.

Weinstein, C.E., & Palmer, D.R. (2002). LASSI user’s manual (2nd ed.) Clearwater, FL: H & H Publishing.

Yilmaz Soylu, M., Zeleny, M. G., Zhao, R., Bruning, R. H., Dempsey, M. S., & Kauffman, D. F. (2017). Secondary students’ writing achievement goals: Assessing the mediating effects of mastery and performance goals on writing self-efficacy, affect, and writing achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01406.

Zhang, D., & Zhang, L. J. (2019). Metacognition and self-regulated learning in second/foreign language teaching. In X. A. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 883–898). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02899-2_47.

Zhang, J., Zhang, L. J., & Zhu, Y. (2023). Development of a genre-based second language writing self-efficacy scale. Frontier in Psychology, 14, 1181196. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1181196

Zhang, L. J. (2016). Reflections on the pedagogical imports of western practices for professionalizing ESL/EFL writing and writing-teacher education. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 39(3), 203–232. https://doi.org/10.1075/aral.39.3.01zha.

Zhang, L. J. (2022). L2 writing: Toward a theory-practice praxis. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of practical second language teaching and learning (pp. 331–343). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003106609-27.

Zhang, L. J., Thomas, N., & Qin, T. L. (2019). Language learning strategy research in System: Looking back and looking forward. System, 84, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.06.002.

Zhang, J. (2023). Writer Individual Differences and Writing Performance: A Study of Chinese University English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Student-Writers [PhD thesis, The University of Auckland].

Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(3), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.81.3.329.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2013). From cognitive modeling to self-regulation: A social cognitive career path. Educational Psychologist, 48(3), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2013.794676.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Bandura, A. (1994). Impact of Self-Regulatory Influences on Writing course attainment. American Educational Research Journal, 31(4), 845–862. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312031004845

Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (2002). Acquiring writing revision and self-regulatory skill through observation and emulation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 660–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.660.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Risemberg, R. (1997). Becoming a self-regulated writer: A social cognitive perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22, 73–101.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203839010.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC21883).

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interests in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Zhang, L. Exploring the profiles of foreign language learners’ writing self-regulation: focusing on individual differences. Read Writ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-024-10568-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-024-10568-x