Abstract

Processing efficiency theory can explain the relationship between anxiety and academic success; however, its application to adults with Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) remains unclear, especially in a nonalphabetic language, such as Chinese. This study investigated the effects of working memory and processing speed on the relationships between state anxiety and academic performance of university students with and without SLD in Chinese. A sample of 223 s-year undergraduate students was recruited from universities in southern Taiwan; 123 were typical learners, while the remaining 100 were identified as having SLD. We found distinct profiles in the relationships between state anxiety, working memory, processing speed, and academic performance. The interaction between state anxiety and working memory was also predictive of the academic performance of university students with SLD, highlighting the negative impact of state anxiety on those students who performed poorly in working memory tasks. Our findings emphasize the importance of cognitive and psychological factors in contributing to the learning of students with SLD. Furthermore, the effects of working memory and state anxiety on academic performance, particularly in students with SLD, could inform the design of teaching materials and procedures, especially regarding the levels of difficulty and volumes of learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) are learning difficulties that affect one or more cognitive processes involved in learning. These difficulties may manifest in an inability to perform specific tasks such as listening, thinking, speaking, writing, spelling, or calculating, subsequently affecting academic performance (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Although SLD is defined as learning difficulties not directly leading to emotional disturbances, many individuals with SLD do exhibit a higher degree of negative emotions (Sahoo et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2021). However, only a few studies have examined such issues. Past decades of research have shown that children with SLD experience worse emotional states than their peers (Al-Yagon, 2015). This population also tends to experience various psychological problems, such as concentration and motivation issues, particularly under circumstances that trigger worries, namely, state anxiety (e.g., Carroll, 2015; Carroll & Iles, 2006). When negative emotions become overwhelming, they can affect individuals’ academic performance by interacting with cognition (Joshi & Aaron, 2012). This impact has been reported across various age levels by both Western (e.g., Carroll & Iles, 2006; Nelson et al., 2015) and Eastern cultures, including Chinese (Wang, 2019; Wang et al., 2021, 2022; Xiao et al., 2022). Thus, overlooking the situation-specific emotional disturbance (i.e., state anxiety) of individuals with SLD may prevent us from gaining a clearer picture of their learning portfolios.

Although the effects of anxiety on academic performance have been studied and are generally shown to be negative (for a review, see Francis et al., 2019), the mechanisms through which anxiety influences academic performance remain unclear (Carey et al., 2017). The Component Model of Reading (Joshi & Aaron, 2012) suggests that several factors, including ecological (Fayegh et al., 2010), sociological (El-Anzi, 2005), and cognitive factors (Thomas et al., 2017), may influence this relationship. A notable consideration is working memory, a cognitive function involved in the processing and temporary storage of information (Baddeley et al., 2021). Its complex role in the relationship between anxiety and academic achievement has been preliminarily discussed (Eysenck et al., 2005).

The impact of working memory on the relationship between anxiety and academic achievements could refer to Processing Efficiency Theory (Eysenck & Calvo, 1992; Eysenck et al., 2005), which posits that anxiety can affect an individual’s processing efficiency and, accordingly, have various negative effects on performance. Scholars like Markham and Darke (1991) supported the theory that anxiety can affect a person's ability to perform complex tasks by consuming their cognitive resources. These views align with Sweller’s (2010) cognitive load theory, suggesting that those with higher anxiety remember less content than those with lower anxiety, as the limited capacity of working memory is occupied by anxiety. Consequently, studies have tested Processing Efficiency Theory by directly examining the role of working memory in the relationships between anxiety and academic performance. For instance, Ashcraft and Kirk (2001) reported a negative correlation between working memory and anxiety toward mathematics learning in undergraduates. Their second experiment confirmed that under conditions where individuals' working memory is heavily taxed, performance deteriorates significantly for the high-anxiety group but not for the low- or medium-anxiety groups. In other words, anxiety may have differential impacts on achievement depending on individuals' levels of working memory, suggesting a clear moderating effect of working memory on this relationship. These findings have also been corroborated and extended to other subjects and age groups in several recent studies. For instance, Cuder et al. (2023) reported a significant moderating effect of visuospatial working memory on the relationship between math anxiety and math learning (i.e., numerical operations and mathematical reasoning) among 4th to 6th graders who are typically developing in primary school. Similar findings across different age groups have been reported in studies that considered both verbal and visuospatial working memory, such as those by Owens et al. (2014) (1st to 3rd graders who are typically developing in secondary school) and van Dijck et al. (2022) (typically developing adults).

Considering the moderating effect of working memory, individuals with SLD, who often have limited working memory capacity (Swanson, 2020), may be more susceptible to adverse effects in high-anxiety situations. This could affect the relationship between anxiety and academic achievement. Although this notion is compelling, very few studies have empirically examined the interrelationships among working memory, anxiety, and academic performance in individuals with SLD. An exception is the study by Prevatt et al. (2010), which found that the capacity to maintain memory over extended periods—a factor closely related to working memory—could significantly moderate the relationship between anxiety and academic performance among undergraduates with SLD. Specifically, they observed a significant predictive relationship from anxiety to academic performance in the low-anxiety group but not in the high-anxiety group.

In the broader research context related to Processing Efficiency Theory, processing speed has been identified as a critical factor that reflects the efficiency and rapidity of cognitive processing (Tomporowski et al., 2015). This factor has been shown to interact with working memory to constitute what is termed an individual's processing efficiency (Paas & Sweller, 2012). Theoretically, processing speed and working memory are not isolated constructs; rather, they are interrelated and often operate in tandem during learning processes. Particularly in the execution of complex and novel tasks, the rate at which information is processed directly influences the efficiency with which it can be stored and manipulated within working memory (Repovš & Baddeley, 2006). Conversely, a reduction in processing speed could result in an overload of working memory, thereby compromising its efficiency. This could potentially result in a decline in academic performance (Kail & Hall, 1994; Fry & Hale, 2000).

The relationship between processing speed and working memory is especially pertinent in individuals with Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD). The inherent challenges these individuals encounter in terms of processing speed can lead to a constriction in the flow of information, commonly referred to as a 'bottleneck.' This constriction may negatively impact working memory, with potential downstream consequences for academic achievement (Wang et al., 2022).

Moreover, the link between processing speed and academic performance has been shown to exert an indirect influence on state anxiety. A reduced processing speed may require increased effort in task execution, extend completion times, and foster a perception of falling behind peers. These factors, in aggregate, may serve as catalysts for the onset or exacerbation of anxiety (Channon & Green, 1999). Empirical evidence from both clinical and educational settings has highlighted a correlation between diminished processing speed and elevated levels of anxiety (Boswell et al., 2013). Additionally, Wang et al. (2022) reported distinct patterns among Chinese children with and without SLD. They specifically found that, for those with reading disabilities, processing speed acts as a mediator in the relationship between state anxiety and reading comprehension. Thus, when testing the Processing Efficiency Theory for a Chinese population with SLD from the role of working memory in the present study, the involvement of processing speed should reasonably be considered to decrease the possible impacts of confounding factors and then further raise the reliability of our findings.

Additionally, it is crucial to acknowledge that the existing body of research, which focuses on exploring the relationships among working memory and/or processing speed, state anxiety, and academic achievement, has been predominantly conducted within the context of alphabetic languages. This focus presents a notable research gap for two primary reasons, including languages and cultures.

Firstly, such relations of anxiety, working memory, and academic performance are also reported to be related to the demands of the stimuli used in the experiments in terms of individuals’ visual processing (e.g., Berggren et al., 2017; Vytal et al., 2013). This introduces a critical consideration—the distinction between alphabetic and logographic languages, each of which relies on different cognitive processes. Alphabetic languages, such as English, possess a linear structure in which each symbol represents a sound. Consequently, individuals' phonological awareness has been consistently reported as the most influential predictor of their reading achievements (Anthony & Francis, 2005). In contrast, logographic languages, such as Chinese, necessitate the recognition of complex characters, each of which represents a word or phrase. This places a significant emphasis on visual-processing skills (Liu et al., 2015). In this regard, the effects proposed by Processing Efficiency Theory, in terms of individuals' literacy skills, could be distinct for reading and writing in the languages demanding. Thus, the findings on alphabetic languages may not be appropriate to directly explain the phenomenon in places where Chinese, a language that is highly visual-processing-reliant for reading and writing (Liu et al., 2015), is the most dominant language. Moreover, accumulating evidence indicates that deficient visual processing may be the most prominent problem Chinese students with SLD face in their academic performance (e.g., Ho et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2019). Thus, the findings of those studies conducted in alphabetic languages may not apply to Chinese populations.

Secondly, the majority of these studies have been predominantly conducted within Western cultures (e.g., North America and Europe), thereby introducing a potential bias in our understanding. Adding complexity to this issue is the cultural context; research has shown that awareness of various degrees of negative mental states, including anxiety, is significantly culture-specific (Hsu & Alden, 2007; Hsu et al., 2012). The influence of culture on the interpretation and experience of anxiety has been robustly substantiated by numerous studies (Scollon et al., 2004), leading to an increasing call for the consideration of cross-cultural applicability in establishing a universally accepted definition of anxiety disorders (Lewis-Fernández et al., 2010). Despite this nuanced understanding of the emotional conditions affecting reading, a substantial number of studies have neglected other essential aspects, such as reading-related abilities, as highlighted by Aaron et al. (2008). This significant omission accentuates a critical research gap that warrants attention. As a result, it underscores the imperative to conduct comprehensive and culturally sensitive research that explores the impact of anxiety on a broader range of academic achievements.

Taken together, the interaction between anxiety and the working memory of people with SLD and their impacts on dealing with tasks with high levels of complexity could vary by culture. Thus, the majority of the current findings in this issue cannot be simply extended to people who do not live in a non-Western and non-alphabetic native language place, such as Chinese contexts. However, to the best of our knowledge, very few studies have been conducted to test Processing Efficiency Theory for Chinese populations with SLD, and this is a crucial issue that must be resolved.

The present study

We aimed to investigate the impacts of working memory on the relationships between state anxiety and academic performance of university students with and without Chinese SLD. Specifically, this study had two parts: (1) testing whether the interaction of groups of participants, state anxiety, and working memory contribute to academic performance and (2) examining the moderation effects of working memory in the relationship between state anxiety and academic performance along with processing speed in undergraduate students with and without SLD.

Methods

Research design

This study aims to investigate whether working memory can moderate the relationships between state anxiety and the academic performance of university students with and without Chinese SLD. Given the distinct cognitive profiles observed in Chinese individuals with and without SLD (e.g., Chung et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021, 2022, 2023), our initial objective is to ascertain whether such differences are present in our study sample. Specifically, drawing upon previous studies with similar designs (e.g., Moll et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018), we aim to examine whether the symptoms of SLD (i.e., the Group condition in this study) interact with working memory and state anxiety to affect academic performance. If such interactions are observed, they should not manifest in the same patterns when testing our primary hypothesis. Should the distinctions in the cognitive profiles of the two groups be confirmed, we will then examine and compare the moderating effect of working memory on the predictive relationship from state anxiety to academic achievement for each group.

Our study is driven by substantial evidence highlighting the critical role of working memory in learning and cognitive processing, especially in educational contexts (Bergman Nutley & Söderqvist, 2017). While non-verbal IQ, as measured by Raven's scores, and processing speed are relevant cognitive factors, we strategically emphasize working memory due to its direct and significant contributions to academic performance. This decision aligns with key studies showing the profound impact of working memory on learning outcomes, surpassing general IQ measures (Gathercole et al., 2004; Bull et al., 2008). Therefore, our focus on working memory is vital as it offers a detailed understanding of how it interacts with state anxiety to affect academic achievements, particularly in students with SLD. This specific concentration, while potentially overlooking aspects like Group X Processing Speed or Group X Raven score interactions, is crucial for unpacking the unique dynamics in this student population.

Participants

We recruited 223 s-year undergraduate students from two public and three private universities in central and southern Taiwan (n = 52, 46, 48, 41, and 36 respectively). The participants had diverse backgrounds, such as social science, engineering, nursing, and transportation. Additionally, they have the same language background – they were all monolingual before entering school systems, and their native language is Chinese. They were not selected because of their attendance in any particular courses/programs. Among all of the participants, 100 hold the official identification of SLD in Taiwan (male = 42; n = 24, 21, 22, 18, and 15 in each university).

In Taiwan, students with a history of SLD were invited to seek to reidentify themselves as individuals with this condition as they transitioned to university. This process is carried out by a government-appointed committee composed of professionals, such as teachers and psychologists. The primary goal of identifying people with SLD is to determine whether they have an identification history that indicates they have the condition at a recent educational level (i.e., secondary school level). They also want to determine whether their symptoms significantly affect their learning. For those who have not previously identified themselves as individuals with this condition, a stricter process would be conducted for them when they apply for the individual first identification of SLD at university. For instance, more psychological and linguistic measures may need to be applied to them to precisely determine the status of their learning difficulties, and this procedure is similar to the identification of SLD at other educational levels.

The other group consisted of 123 typically developing undergraduate students (male = 54; n = 28, 25, 26, 23, and 21 in each university), who were matched with individuals with SLD in terms of their gender, grades, major, and university. For gender matching, 100 typically developing students were precisely matched with those with SLD, and the gender ratio among the remaining 23 students was approximately one-to-one. To recruit these individuals, we approached their classmates with SLD. At least one student was recruited from each university, where we recruited every participant with SLD in the present study. The students had no history of having any type of special education or neurologic disorders. Their characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Measures

The participants underwent a series of cognitive ability tasks and completed an anxiety inventory to address the research aims of the present study. Ethical review approval was granted by the institution with which the second author is affiliated. Given that all participating students were adults, only their individual consent was required to proceed with the screening procedure.

Raven's advanced progressive Matrices–Parallel

This standardized test was designed to test adolescents’ and adults’ visual reasoning abilities, which was measured as nonverbal IQ in past research (e.g., Wang, 2021; Wang & Yang, 2018; Wang et al., 2021). There are 60 items with increasing difficulty in this test, and each item has a target visual matrix with one missing part. The participants were asked to select the response that completes the missing piece in the visual matrix from six to eight response options. The final score was generated by referring to the Taiwanese norm (Chen & Chen, 2006). The manual shows that test–retest reliability was measured as 0.87 and was tested over a 32-day period. Cronbach’s α coefficient based on the sample in this study was 0.85.

Processing speed task

We used the rapid naming task to test processing speed in this study; it was designed to test individuals’ speed in verbally naming visual stimuli one at a time. The selection of the rapid naming task as an assessment tool was motivated by the premise that it effectively captures aspects of processing speed. This is based on the task's requirement for quick and accurate naming of stimuli, making it a suitable behavioral proxy for this cognitive process (Shanahan et al., 2006). However, it is worth noting that a counterargument exists, suggesting that rapid naming involves more complex cognitive processing (Kail & Hall, 1994). Despite this contention, numerous studies have continued to employ the rapid naming task as a favored measure within the unitary model of processing speed, utilizing it as an index for gauging processing speed (e.g., Gooch et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022).

This task was adapted from comparable measures used in preceding research (e.g., Liu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2022). Specifically, the individuals were asked to study aloud unpaired digit numbers arranged on a single page of the paper in a 5 (row) × 6 (column) array as fast as possible. Only five numbers (i.e., 1, 2, 5, 6, and 8) were included in this undertaking and indexed in a randomized order in every row. Every participant completed the task twice, and the participant’s completion times were recorded. The average completion time was the score for this task. The Cronbach’s α coefficient based on our sample was 0.92.

Working memory task

In this study, we used one of the most well-known tasks to test the participants’ working memory: the backward digit span (Botwinick & Storand, 1974). We selected the backward digit span task for its high construct validity (Waters & Caplan, 2003) and proven effectiveness in psychological and neuropsychological assessments. This task is recognized for its sensitivity to changes in working memory and has been used in various cognitive evaluation studies, including those involving conditions like dementia (Pickering & Gathercole, 2001; Wang & Chung, 2018; Yoshimura et al., 2023). Its ability to assess the central executive component of working memory makes it particularly relevant and suitable for our study's focus on the relationship between working memory, state anxiety, and academic performance.

In this task, sequences of random digits were presented verbally one after another at approximately one-second intervals, and the participants were asked to produce the digits in reverse order. The number of digits varied from three to nine; there were two trials for each number, and the participant earned one point for reporting the correct digit with the correct reversal order for any trial. The maximum score of this test is 14. The task was stopped when the participant failed in both trials of one number. Cronbach’s α coefficient based on the sample in this study was 0.93.

State anxiety inventory

We used the state anxiety subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, which Spielberger (1983) developed to assess individuals’ levels of state anxiety. This subscale consists of twenty items measured on a four-point Likert scale; higher scores indicate greater state anxiety. Wang and Chung (2016) translated and examined the Chinese version of this inventory and found an excellent convergent validity of 0.90. Although half of the participants in the present study had SLD, we offered the text-to-speech service, if necessary, to ensure they all have a sufficient understanding of the meanings of the items’ descriptions by converting the written descriptions into spoken words. Of those with SLD, 47 participants requested and were thus provided with this auditory aid. Cronbach’s α coefficient based on the sample in this study was 0.91.

Academic performance

In the present study, we used the students’ overall GPAs in year one at the university to indicate academic performance. This design was based on past similar studies that recruited students at similar educational levels (e.g., Goroshit & Hen, 2021). This is also because the participants are at the university level studying diverse majors, which makes using specific measures to determine their academic performance very difficult and unreliable.

Data analysis

Multiple statistical methods were used to examine the present study's research aims. Since the participants came from different universities, their GPAs were challenging to compare directly and be able to serve as an objective variable. Thus, we normalized this index into a Z-score. This was achieved by taking an individual student's GPA, subtracting the mean GPA of their specific school, and then dividing the result by the standard deviation of the GPA within that school.

Also, the examination of various factors revealed that many of them are closely related to one another, based on the literature review conducted, and this close relationship raises the potential for multicollinearity problems, which could lead to unreliable and unstable estimates of regression coefficients. To mitigate the risk of multicollinearity, we implemented a standardization process for the unstandardized variables involved in the study. Specifically, the variables of state anxiety, working memory, and processing speed were transformed into standardized Z-scores. This transformation involves subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation for each variable, thereby ensuring that each has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. This procedure could help reduce multicollinearity because it is able to rescale variables on a common footing, mitigating the issue when variables have vastly different scales (Fahrmeir et al., 2013). Also, this function is likely to benefit because it could center variables, which could introduce spurious correlations between previously uncorrelated variables (Menard, 2010).

After completing the necessary transformations of the scores, we proceeded to conduct a bivariate correlation analysis on all the variables involved. This analysis was essential to ascertain the pairwise relationships between each variable, providing insights into their interconnections and potential collinearity. Subsequently, a linear regression analysis was used to test whether state anxiety and working memory interact with the group of participant to contribute to academic performance. Furthermore, to examine the moderation effects of working memory on the relationship between state anxiety and academic performance in Chinese undergraduates with and without SLD, we used moderation analyses to test the relational patterns of the two groups separately. By examining these patterns, we aimed to identify whether there were significant differences in how working memory moderated the relationship between state anxiety and academic performance across the two groups.

Results

First, we examined the correlations among all variables involved in the present study, and the findings are presented in Table 2. From this set of results, it is evident that, in most instances, state anxiety, working memory, and processing speed exhibit significant correlations with one another. Conversely, the relationships between these variables and demographic factors—namely, non-verbal IQ, age, and gender—appeared less pronounced. Notably, none of these cognitive or emotional variables demonstrated a significant correlation with gender; therefore, only non-verbal IQ and age were retained for subsequent analyses.

Additionally, a linear regression analysis was used to test whether the interactions between a group of participants, working memory, and state anxiety significantly contributed to academic performance. In this analysis, the independent variables were age, nonverbal IQ, processing speed, groups of participants, working memory, state anxiety, and the interaction of groups of participants, state anxiety, and working memory, and the dependent variable was the participants’ academic performance. The results are shown in Table 3.

Before this analysis, we implemented a similar linear regression without two interactions created to test the similarity of the natures of two groups, and the variance inflation factors (VIFs) of all variables, which were used to check collinearity among the constructs, were all between 1.07 and 1.84. These results are considered ideal, indicating no significant multicollinearity among the independent variables, including all variables and the interactions, with the dependent variable in our regression models (O’brien, 2007).

According to the results in Table 3, the contribution from the interaction of the groups of participants, state anxiety, and working memory with academic performance is significant. Therefore, it could be preliminarily concluded that students with and without SLD exhibit distinct working memory and state anxiety patterns related to academic performance, as suggested in previous studies (e.g., Wang et al., 2022). Thus, we implemented further analyses to examine the moderation of working memory in the contributions of state anxiety to academic performance, conducted separately for undergraduates with and without SLD to address the second research aim.

To investigate the effects of state anxiety and working memory on academic performance, we conducted separate moderation effect analyses for students with and without SLD. We referred to Hayes (2017) and used Model Number 1 of the PROCESS macro for SPSS with 5,000 bootstrap samples. The results of the two groups are summarized in Table 4. The results of typically developing students show significant predictive effects of state anxiety (p < 0.05) and working memory (p < 0.05) on academic performance, in addition to their processing speed. However, the interaction of state anxiety and working memory in this group did not significantly predict academic performance. All the involved variables accounted for 37.54% of academic performance at a significant level [F(6, 116) = 11.62, p < 0.00].

As the results show in the right part of Table 4, for students with SLD, the predictive contributions of both state anxiety and working memory to their academic performance were not significant (p > 0.05 for both). Importantly, the interaction between state anxiety and working memory significantly predicted the academic performance of students with SLD (p < 0.05), explaining 2.52% of the variance in academic performance [F(1, 92) = 3.92, p < 0.05].

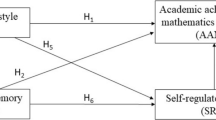

As Hayes and Matthes (2009) suggested, we used the Johnson–Neumann (J–N) technique with 5,000 bootstrap samples to further characterize this interaction. The J–N technique could identify points in the range of the moderator variable (i.e., working memory) where the effect of the predictor on the outcome (i.e., academic performance) transitions from statistically significant to insignificant by finding the value of the moderator variable (Xu et al., 2020). The conditional effect of state anxiety on academic performance for SLD is significant at a working memory (Z-score) of − 0.19, ß = − 0.20, SE = 0.00, t = − 1.99, p = 0.05, 95% CIs [− 0.4022, 0.0000], corresponding to the 48th percentile of our sample’s distribution. The relation between state anxiety and academic performance was negatively significant, with the Z-score of working memory smaller than − 0.19. Nevertheless, such a relationship was no longer significant for larger working memory values. The interactions between state anxiety and working memory on academic performance performance could be illustrated in Fig. 1.

In summary, our results confirmed the distinct profiles in the relations among state anxiety, working memory, processing speed, and academic performance. Specifically, for university students with typical development, working memory, but not state anxiety, significantly contributed to their academic performance. However, there was no significant predictive effect of the interaction between state anxiety and working memory on academic performance for this group. In contrast, for university students with SLD, the interaction between state anxiety and working memory significantly contributed to academic performance. Additionally, state anxiety negatively impacted the academic performance of participants in this group for those who performed relatively poorly in working memory.

Discussion

This study investigated the impact of working memory on the relationships between state anxiety and academic performance among university students with and without Chinese SLD. We are among the first to provide evidence regarding the distinct profiles of relationships between state anxiety, working memory, and academic performance among Chinese undergraduates with and without SLD.

The interaction between state anxiety and working memory in contributing to the academic performances of the two groups

We discovered that the interaction between participant groups (i.e., with and without SLD) and state anxiety significantly contributed to academic performance, potentially explained by the distinct cognitive profiles of the two groups. These findings partially echo previous studies that revealed university students with SLD have different profiles of cognitive ability deficits and emotional disturbances compared to their peers, both in alphabetic (e.g., Conway et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2015) and nonalphabetic languages, such as Chinese (e.g., Wang et al., 2021).

It is noteworthy that most examinations of distinct patterns in individuals with SLD, or similar populations, have primarily focused on children or adolescents, with few conducted on adults. These examinations suggest heterogeneous natures and multifactorial deficits in students with SLD when targeting children or adolescents, typically comparing them with typically developing peers of similar chronological ages or reading levels (e.g., Tobia & Marzocchi, 2014; Wang & Yang, 2018). However, designing similar research for adults with SLD is challenging due to the broader age range at the adult level. In this regard, concepts like high-functioning and typical-functioning SLD (e.g., Birch & Chase, 2004; Chung et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021) may offer a feasible approach. Students diagnosed with SLD in childhood who achieve functional or normal literacy skills enabling them to study at higher levels can be considered to have high-functioning SLD, while those with persistently deficient literacy skills are seen as having typical-functioning SLD. This classification provides another perspective to understand the heterogeneous nature and multifactorial deficits of adults with SLD compared to typically developing students.

Moderation effects of working memory on the relationship between state anxiety and academic performance in undergraduates with and without SLD

The predictive effect of the interaction between working memory and state anxiety on academic performance varies between Chinese undergraduates with and without SLD. The key finding of this study is the identification of working memory's importance in the aforementioned relationship, particularly for those with SLD. Specifically, adverse impacts from state anxiety on academic performance occurred only for those with SLD and poor working memory. According to Processing Efficiency Theory, individuals' concerns over situational threats (i.e., state anxiety) can occupy a portion of the total processing capacity of the working memory system, particularly the central executive (Baddeley et al., 2021). Thus, higher levels of state anxiety result in fewer available cognitive resources for processing complex tasks. This issue is particularly pronounced in individuals with SLD, who often have limited working memory capacity and continue to face difficulties into adulthood, affecting their storage performance (Smith-Spark & Fisk, 2007). However, considering cultural specificities regarding anxiety (Abbassi & Stacks, 2007), our findings are intriguing as we are the first to assert that Processing Efficiency Theory (Eysenck et al., 2005) can also apply to Chinese-speaking undergraduates, specifically those with SLD.

The nonsignificant interaction between working memory and state anxiety among those without SLD contributing to academic performance aligns with previous findings. For instance, Chow et al. (2021) found no significant interaction between reading anxiety and verbal working memory in typically developing undergraduates in Hong Kong. Although these studies used different dependent variables, they both represent complex processing tasks. This finding suggests a possible universal phenomenon regarding the relationships between anxiety and working memory toward processing complex tasks in Chinese contexts.

The potential oversimplification of working memory capacity by using the backward verbal digit span task could be a factor in the inconsistent phenomenon. This task relies more on the central executive than on the phonological loop or visuospatial sketchpad (Grégoire & Van der Linden, 1997). The developmental trajectories of multiple working memory components from childhood to adulthood (Heled et al., 2022) suggest that a unicomponential test of working memory may not fully capture the whole picture (Dudchenko, 2004). Additionally, the demands of Chinese, as a logographic language, on working memory, particularly emphasizing visual-processing skills (Liu et al., 2015; Zimmer & Fischer, 2020), are pertinent for students with SLD, who often exhibit deficiencies in visual processing (Ho et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, it is not surprising that we found a significant interaction between state anxiety and working memory affecting academic performance. The visual complexity of Chinese characters could exacerbate the negative impact of state anxiety on working memory, thereby further hindering academic performance (Zimmer & Fischer, 2020). This linguistic specificity provides an additional layer of explanation for our findings, particularly concerning the differential impact of state anxiety on students with SLD.

Cultural factors also play a significant role. The experience and interpretation of state anxiety are heavily influenced by cultural norms and expectations (Hsu & Alden, 2007; Hsu et al., 2012; Tavassoli, 2002). In Chinese culture, where academic performance is highly valued, the experience of state anxiety could be intensified, placing additional strain on working memory (Tavassoli, 2002). Our study not only contributes to the existing literature by examining these relationships in a non-alphabetic language but also highlights the need for future research to consider the complex interplay of language and culture in understanding the cognitive and psychological factors contributing to academic performance.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, since the participants in the present study came from several universities in multiple cities in Taiwan, it is unavoidable that the GPAs of the students from the universities at different levels may be inequivalent (Soh, 2010). Thus, it is crucial to address a limitation related to the use of GPA as an indicator of academic performance. Although GPA serves as a broad representation of a student's school performance, its lack of specificity—compared to discrete metrics like reading or mathematics scores—can also complicate its interpretation. This aggregate measure, encompassing the influence of both effort and inherent abilities, provides a comprehensive snapshot of students' learning outcomes. For this reason, GPA has seen extensive use in academic studies over the years, particularly in research concerning college and university students (e.g., Chapell et al., 2005; Lepp et al., 2014). Nevertheless, it's essential to acknowledge that the GPA is susceptible to various influences (Richardson et al., 2012). As such, in the present study, we normalized the GPA from different universities to minimize the possible bias caused by using this synthesis index, but even so, caution is warranted when interpreting the GPA, recognizing its potential to be impacted by a myriad of factors. Therefore, any conclusions drawn from studies using GPA as a measure should be considered in light of these complexities.

Secondly, in our participant selection process, it is evident that our priority population was students with SLD, followed by their classmates, who served as the control group. However, during this process, we were limited in our ability to match the number of credit hours taken by each participant in the last academic year. While the number of credit hours may not offer substantial insights into individual students, it could, at the very least, influence the interpretation of the average GPA used as an index of academic performance. In this context, the absence of this information could exert a minor impact on participants' academic performance and potentially influence their self-perception within the university setting, which in turn could affect their levels of state anxiety. Therefore, future research focusing on university-level students is strongly advised to include this index.

Furthermore, despite our meticulous efforts to account for demographic variables such as age, gender, and educational background, completely neutralizing their potential confounding impacts continues to be a formidable challenge in behavioral research, a point echoed by Smith and Noble (2014). This issue acquires heightened significance in studies focused on cognitive and emotional assessments, where demographic factors can exert subtle yet meaningful impacts on outcomes, as illustrated by Johnson et al. (2017). Moreover, Sackett et al. (2004) have astutely noted that demographic variables often interact unpredictably with individual differences, thereby introducing a layer of complexity to the interpretation of research findings. Consequently, while our study has diligently endeavored to control for these variables, it is imperative to acknowledge and consider the inherent limitations in fully mitigating their impact. This consideration is especially crucial in our study's context, which revolves around specific learning disabilities and academic performance. Such an acknowledgment underscores the need for careful interpretation of our findings, bearing in mind the nuanced impacts of these demographic factors.

Also, there are a couple of variables contained in this study, but only working memory, state anxiety, and academic performance were considered as the key variables, as per the theoretical arguments presented above. Thus, we prioritized examining the interaction between working memory and state anxiety in relation to academic performance without involving other variables in the interaction equations. We consciously decided against incorporating a three-way or even four-way interaction to maintain focus and clarity in our model. This decision aligns with common analytical practices, where higher-order interactions are typically reserved for situations necessitating an intricate model fit or when underpinned by strong theoretical grounds. By simplifying our model and maintaining clarity and ensuring robust findings based on the limited sample size in this study (Dawson & Richter, 2006), we aimed to avoid potential misinterpretations and keep the readers' attention on the primary findings, ensuring that the interpretation of our results remains straightforward and focused.

However, it is also notable that the utilization of Raven's IQ test in our study also brings into question the potential overlap between spatial processing and working memory, especially relevant for understanding cognitive processes involved in reading Chinese logographic characters. It's important to consider the argument by Kane et al. (2005) that while Raven's test might involve spatial processing, its correlation with working memory is not solely dependent on spatial abilities. This suggests that our findings, while influenced by the nature of Raven's test, still provide valuable insights into the cognitive functioning of our participants, especially in the context of processing a logographic language.

Finally, different variables, especially working memory and state anxiety, are likely to show a strong correlation even if multicollinearity has been attempted to be reduced by using a standardization procedure (Fahrmeir et al., 2013; Menard, 2010). Although such a significant negative correlation is not just theoretically sound (Eysenck et al., 2007) but also supported by previous studies (e.g., Hadwin et al., 2005), it is still undeniable that the strong correlation between working memory and state anxiety would unavoidably affect the interpretations of the regression results presented in our study. Thus, future studies may consider introducing an experimental design to isolate the impact of these variables.

Despite the limitations listed above, the present study first discloses how working memory can affect the predictive relationship between state anxiety and the academic performance of university students with and without SLD, especially in the Chinese context. We preliminarily confirmed the distinct profiles of the relations of state anxiety, working memory, and academic performance between Chinese undergraduates with and without SLD, especially when processing speed was taken into consideration. Our findings could enhance our understanding in this field and remind everyone of the importance of various factors that can greatly affect the learning of students with SLD, including not only the cognitive domain (e.g., working memory and processing speed) but also the psychological domain (e.g., state anxiety) and how significant their interactions may be. Furthermore, our findings could also be helpful for teachers, parents, and practitioners when the teaching schedules and materials are designed. The emphasis on state anxiety for undergraduates' learning and the impact of working memory, particularly for those with SLD, should be borne in mind when deciding on the difficulty levels and learning volume.

References

Aaron, P. G., Joshi, R. M., Gooden, R., & Bentum, K. E. (2008). Diagnosis and treatment of reading disabilities based on the component model of reading. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219407310838

Abbassi, A., & Stacks, J. (2007). Culture and anxiety: A cross-cultural study among college students. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research, 35(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15566382.2007.12033831

Al-Yagon, M. (2015). Fathers and mothers of children with learning disabilities: Links between emotional and coping resources. Learning Disability Quarterly, 38(2), 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731948713520556

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Cautionary statement for forensic use of DSM-5. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: Author

Anthony, J. L., & Francis, D. J. (2005). Development of phonological awareness. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(5), 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00376.x

Ashcraft, M. H., & Kirk, E. P. (2001). The relationships among working memory, math anxiety, and performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(2), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.130.2.224

Baddeley, A. D., Hitch, G. J., & Allen, R. J. (2021). A multicomponent model of working memory. In R. H. Logy, V. Camos, & N. Cowan (Eds.), Working memory: State of the science (pp. 10–43). Oxford University Press.

Berggren, N., Curtis, H. M., & Derakshan, N. (2017). Interactions of emotion and anxiety on visual working memory performance. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 24, 1274–1281. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-016-1213-4

Bergman Nutley, S., & Söderqvist, S. (2017). How is working memory training likely to influence academic performance? Current evidence and methodological considerations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 69. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00069

Birch, S., & Chase, C. (2004). Visual and language processing deficits in compensated and uncompensated college students with dyslexia. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37(5), 389–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194040370050301

Boswell, J. F., Gallagher, M. W., Sauer-Zavala, S. E., Bullis, J., Gorman, J. M., Shear, M. K., & Barlow, D. H. (2013). Patient characteristics and variability in adherence and competence in cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3), 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031437

Botwinick, J., & Storandt, M. (1974). Memory, related functions and age. Thomas.

Bull, R., Espy, K. A., & Wiebe, S. A. (2008). Short-term memory, working memory, and executive functioning in preschoolers: Longitudinal predictors of mathematical achievement at age 7 years. Developmental Neuropsychology, 33(3), 205–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/87565640801982312

Carey, E., Devine, A., Hill, F., & Szűcs, D. (2017). Differentiating anxiety forms and their role in academic performance from primary to secondary school. PLoS ONE, 12(3), e0174418. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174418

Carroll, C. (2015). A review of the approaches investigating the post-16 transition of young adults with learning difficulties. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(4), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2014.930521

Carroll, J. M., & Iles, J. E. (2006). An assessment of anxiety levels in dyslexic students in higher education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(3), 651–662. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X66233

Channon, S., & Green, P. S. S. (1999). Executive function in depression: The role of performance strategies in aiding depressed and non-depressed participants. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 66(2), 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.66.2.162

Chapell, M. S., Blanding, Z. B., Silverstein, M. E., Takahashi, M., Newman, B., Gubi, A., & McCann, N. (2005). Test anxiety and academic performance in undergraduate and graduate students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(2), 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.268

Chen, J.-H., & Chen, H.-Y. (2006). Raven’s advanced progressive matrices-parallel. Chinese Behavioral Science Corporation.

Chow, B. W. Y., Mo, J., & Dong, Y. (2021). Roles of reading anxiety and working memory in reading comprehension in English as a second language. Learning and Individual Differences, 92, 102092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102092

Chung, K. K. H., Lo, J., & McBride, C. (2018). Cognitive-linguistic profiles of Chinese typical-functioning adolescent dyslexics and high-functioning dyslexics. Annals of Dyslexia, 68(3), 229–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-018-0165-y

Conway, T., Heilman, K. M., Gopinath, K., Peck, K., Bauer, R., Briggs, R. W., & Crosson, B. (2008). Neural substrates related to auditory working memory comparisons in dyslexia: An fMRI study. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 14(4), 629–639.

Cuder, A., Živković, M., Doz, E., Pellizzoni, S., & Passolunghi, M. C. (2023). The relationship between math anxiety and math performance: The moderating role of visuospatial working memory. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 233, 105688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2023.105688

Dawson, J. F., & Richter, A. W. (2006). Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 917–926. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.917

Dudchenko, P. A. (2004). An overview of the tasks used to test working memory in rodents. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 28(7), 699–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.09.002

El-Anzi, F. O. (2005). Academic achievement and its relationship with anxiety, self-esteem, optimism, and pessimism in Kuwaiti students. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 33(1), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2005.33.1.95

Eysenck, M. W., & Calvo, M. G. (1992). Anxiety and performance: The processing efficiency theory. Cognition & Emotion, 6(6), 409–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939208409696

Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336

Eysenck, M., Payne, S., & Derakshan, N. (2005). Trait anxiety, visuospatial processing, and working memory. Cognition & Emotion, 19(8), 1214–1228. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930500260245

Fahrmeir, L., Kneib, T., & Lang, S. (2013). Regression: Models, methods and applications. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-34333-910.1007/978-3-642-34333-9

Fayegh, Y., Rumaya, J., & Talib, M. A. (2010). The effects of family income on test anxiety and academic achievement among Iranian high school students. Asian Social Science, 6(6), 89–93. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v6n6p89

Francis, D. A., Caruana, N., Hudson, J. L., & McArthur, G. M. (2019). The association between poor reading and internalising problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 67, 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.09.002

Fry, A. F., & Hale, S. (2000). Relationships among processing speed, working memory, and fluid intelligence in children. Biological Psychology, 54(1–3), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-0511(00)00051-X

Gathercole, S. E., Pickering, S. J., Knight, C., & Stegmann, Z. (2004). Working memory skills and educational attainment: Evidence from national curriculum assessments at 7 and 14 years of age. Applied Cognitive Psychology: The Official Journal of the Society for Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 18(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.934

Gooch, D., Sears, C., Maydew, H., Vamvakas, G., & Norbury, C. F. (2019). Does inattention and hyperactivity moderate the relation between speed of processing and language skills? Child Development, 90(5), e565–e583. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13220

Goroshit, M., & Hen, M. (2021). Academic procrastination and academic performance: Do learning disabilities matter? Current Psychology, 40(5), 2490–2498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00183-3

Grégoire, J., & Van der Linden, M. (1997). Effect of age on forward and backward digit spans. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 4(2), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825589708256642

Hadwin, J. A., Brogan, J., & Stevenson, J. (2005). State anxiety and working memory in children: A test of processing efficiency theory. Educational Psychology, 25(4), 379–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410500041607

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

Hayes, A. F., & Matthes, J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavioral Research Methods, 41, 924–936. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.3.924

Heled, E., Israeli, R., & Margalit, D. (2022). Working memory development in different modalities in children and young adults. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 220, 105422.

Ho, C. S. H., Chan, D. W. O., Tsang, S. M., & Lee, S. H. (2002). The cognitive profile and multiple-deficit hypothesis in Chinese developmental dyslexia. Developmental Psychology, 38(4), 543. https://doi.org/10.1037//0012-1649.38.4.543

Hsu, L., & Alden, L. (2007). Social anxiety in Chinese-and European-heritage students: The effect of assessment format and judgments of impairment. Behavior Therapy, 38(2), 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.06.006

Hsu, L., Woody, S. R., Lee, H.-J., Peng, Y., Zhou, X., & Ryder, A. G. (2012). Social anxiety among East Asians in North America: East Asian socialization or the challenge of acculturation? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(2), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027690

Johnson, O. E. (2017). Determinants of modern contraceptive uptake among Nigerian women: Evidence from the national demographic and health survey. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 21(3), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i3.8

Joshi, R. M., & Aaron, P. G. (2012). Componential model of reading (CMR) validation studies. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(5), 387–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219411431240

Kail, R., & Hall, L. K. (1994). Processing speed, naming speed, and reading. Developmental Psychology, 30(6), 949–954. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.30.6.949

Kane, M. J., Hambrick, D. Z., & Conway, A. R. A. (2005). Working memory capacity and fluid intelligence are strongly related constructs: Comment on Ackerman, Beier, and Boyle (2005). Psychological Bulletin, 131(1), 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.1.66

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2014). The relationship between cell phone use, academic performance, anxiety, and satisfaction with life in college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.049

Lewis-Fernández, R., Hinton, D. E., Laria, A. J., Patterson, E. H., Hofmann, S. G., Craske, M. G., & Liao, B. (2010). Culture and the anxiety disorders: Recommendations for DSM-V. Depression and Anxiety, 27, 212–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20647

Liu, D., Chen, X., & Chung, K. K. (2015). Performance in a visual search task uniquely predicts reading abilities in third-grade Hong Kong Chinese children. Scientific Studies of Reading, 19(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2015.1030749

Markham, R., & Darke, S. (1991). The effects of anxiety on verbal and spatial task performance. Australian Journal of Psychology, 43(2), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049539108259108

Menard, S. W. (2010). Logistic regression: From introductory to advanced concepts and applications. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483348964

Moll, K., Hulme, C., Nag, S., & Snowling, M. J. (2015). Sentence repetition as a marker of language skills in children with dyslexia. Applied Psycholinguistics, 36(2), 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716413000209

Nelson, J. M., Lindstrom, W., & Foels, P. A. (2015). Test anxiety among college students with specific reading disability (dyslexia) nonverbal ability and working memory as predictors. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48(4), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219413507604

O’brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity, 41(5), 673–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6

Owens, M., Stevenson, J., Hadwin, J. A., & Norgate, R. (2014). When does anxiety help or hinder cognitive test performance? The role of working memory capacity. British Journal of Psychology, 105(1), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12009

Paas, F., & Sweller, J. (2012). An evolutionary upgrade of cognitive load theory: Using the human motor system and collaboration to support the learning of complex cognitive tasks. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9179-2

Pickering, S., & Gathercole, S. E. (2001). Working memory test battery for children (WMTB-C). Psychological Corporation.

Prevatt, F., Welles, T. L., Li, H., & Proctor, B. (2010). The contribution of memory and anxiety to the math performance of college students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 25(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5826.2009.00299.x

Repovš, G., & Baddeley, A. (2006). The multi-component model of working memory: Explorations in experimental cognitive psychology. Neuroscience, 139(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.12.061

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026838

Sackett, P. R., Hardison, C. M., & Cullen, M. J. (2004). On interpreting stereotype threat as accounting for African American-white differences on cognitive tests. American Psychologist, 59(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.7

Sahoo, M. K., Biswas, H., & Padhy, S. K. (2015). Psychological co-morbidity in children with specific learning disorders. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 4(1), 21–25. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.152243

Scollon, C. N., Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2004). Emotions across cultures and methods. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35, 304–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022104264124

Shanahan, M. A., Pennington, B. F., Yerys, B. E., Scott, A., Boada, R., Willcutt, E. G., & DeFries, J. C. (2006). Processing speed deficits in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and reading disability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34(5), 584–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9037-8

Smith, J., & Noble, H. (2014). Bias in research. Evidence-Based Nursing, 17, 100–101. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2014-101946

Smith-Spark, J. H., & Fisk, J. E. (2007). Working memory functioning in developmental dyslexia. Memory, 15(1), 34–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210601043384

Soh, K. C. (2010). Grade point average: What’s wrong and what’s the alternative? Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 33(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2011.537009

Spielberger, C. D. (1983). Manual for the state-trait-anxiety inventory: STAI (form Y). Consulting Psychologists Press.

Swanson, H. L. (2020). Specific learning disabilities as a working memory deficit. In A. J. Martin, R. A. Sperling, & K. J. Newton (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology and students with special needs (pp. 15–48). Taylor & Francis.

Sweller, J. (2010). Element interactivity and intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Educational Psychology Review, 22(2), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9128-5

Tavassoli, N. T. (2002). Spatial memory for Chinese and English. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(4), 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222102033004004

Thomas, C. L., Cassady, J. C., & Heller, M. L. (2017). The influence of emotional intelligence, cognitive test anxiety, and coping strategies on undergraduate academic performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 55, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.03.001

Tobia, V., & Marzocchi, G. M. (2014). Cognitive profiles of Italian children with developmental dyslexia. Reading Research Quarterly, 49(4), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.77

Tomporowski, P. D., McCullick, B., Pendleton, D. M., & Pesce, C. (2015). Exercise and children’s cognition: The role of exercise characteristics and a place for metacognition. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 4(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.09.003

van Dijck, J. P., Fias, W., & Cipora, K. (2022). Spatialization in working memory and its relation to math anxiety. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1512(1), 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14765

Vytal, K. E., Cornwell, B. R., Letkiewicz, A. M., Arkin, N. E., & Grillon, C. (2013). The complex interaction between anxiety and cognition: Insight from spatial and verbal working memory. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 93. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00093

Wang, K.-C., & Chung, F.-C. (2016). An investigation of multidimensional factorial validity of the Chinese version of state-trait anxiety inventory. Psychological Testing, 63(4), 287–313.

Wang, L. C. (2021). Anxiety and depression among Chinese children with and without reading disabilities. Dyslexia, 27(3), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.1691

Wang, L. C., Chen, J. K., & Poon, K. (2023). Relationships between state anxiety and reading comprehension of Chinese students with and without dyslexia: A cross-sectional design. Learning Disability Quarterly, Advanced Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/07319487221149413

Wang, L. C., Chen, J. K., & Tsai, H. J. (2022). Anxiety and reading comprehension of Chinese children with and without reading disabilities: The role of processing speed. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 37(2), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/ldrp.12279

Wang, L. C., & Chung, K. K. H. (2018). Co-morbidities in Chinese children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and reading disabilities. Dyslexia, 24(3), 276–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.1579

Wang, L. C., Li, X., & Chung, K. K. H. (2021). Relationships between test anxiety and metacognition in Chinese young adults with and without specific learning disabilities. Annals of Dyslexia, 71(1), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-021-00218-0

Wang, L. C., Liu, D., Chen, J. K., & Wu, Y. C. (2018). Processing speed of dyslexia: The relationship between temporal processing and rapid naming in Chinese. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 31(7), 1645–1668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9857-2

Wang, L. C., Liu, D., & Xu, Z. (2019). Distinct effects of visual and auditory temporal processing training on reading and reading-related abilities in Chinese children with dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia, 69(2), 166–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-019-00176-8

Wang, L. C., & Yang, H. M. (2018). Temporal processing development in Chinese primary school–aged children with dyslexia. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 51(3), 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219416680798

Waters, G. S., & Caplan, D. (2003). The reliability and stability of verbal working memory measures. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 35(4), 550–564. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03195534

Xiao, P., Zhu, K., Liu, Q., Xie, X., Jiang, Q., Feng, Y., & Song, R. (2022). Association between developmental dyslexia and anxiety/depressive symptoms among children in China: The chain mediating of time spent on homework and stress. Journal of Affective Disorders, 297, 495–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.120

Xu, Z., Wang, L. C., Liu, D., Chen, Y., & Tao, L. (2020). The moderation effect of processing efficiency on the relationship between visual working memory and Chinese character recognition. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1899. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01899

Yoshimura, T., Osaka, M., Osawa, A., & Maeshima, S. (2023). The classical backward digit span task detects changes in working memory but is unsuitable for classifying the severity of dementia. Applied Neuropsychology Adult, 30(5), 528–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2021.1961774

Zimmer, H. D., & Fischer, B. (2020). Visual working memory of Chinese characters and expertise: The expert’s memory advantage is based on long-term knowledge of visual word forms. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 516. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00516

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all those who participated in the study, including the participants and liaisons in the universities.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Education University of Hong Kong. This study was partially supported by a grant from Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (110-2410-H-007-010-MY2) and Ministry of Education, Taiwan (Yushan Young Fellow Program) to Dr. Li-Chih Wang as well as a grant from Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (GRF:18611616) to Prof. Kevin Kien Hoa Chung.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, LC., Chung, K.KH. & Jhuo, RA. The relationships among working memory, state anxiety, and academic performance in Chinese undergraduates with SLD. Read Writ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-024-10520-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-024-10520-z