Abstract

Foreign language anxiety has influenced reading achievement in English as a second language learning (ESL). However, less is known about how foreign language anxiety affects Chinese students learning English as L2 and the interplay between foreign language anxiety and cognitive-linguistic factors on L2 reading performance. This longitudinal study examined the impact of foreign language anxiety on English word reading and the mediating effect of cognitive-linguistic skills between foreign language anxiety and English word reading in a sample of 177 grades 2 to 3 ESL Chinese students at risk of English learning difficulties. Foreign language anxiety was assessed using parent-rated and child-rated questionnaires at T1. Students were assessed on English word reading at T1 and T2 and cognitive-linguistic skills: phonological awareness, expressive vocabulary knowledge, and working memory at T1. Path analysis showed that parent-rated foreign language anxiety significantly predicted T1 English word reading after controlling for working memory. However, child-rated foreign language anxiety did not significantly predict English word reading. Moreover, mediation analysis showed that parent-rated foreign language anxiety significantly predicted T2 English word reading through T1 English word reading and expressive vocabulary knowledge. Findings highlight the impact of foreign language anxiety on L2 word reading and suggest that mothers’ involvement in children’s ESL is essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between anxiety and language learning among second and foreign-language learners (see review studies by Toyama & Yamazaki, 2021; Zhang, 2019b). A recent meta-analysis suggests that compared to typically developing readers, struggling readers are particularly prone to anxiety issues (Francis et al., 2019). Although there has been increasing attention to the negative influence of anxiety on first language (L1) reading achievement in Chinese (e.g., Wang et al., 2023), research examining the role of anxiety in foreign language learning for students with reading difficulties is remarkably sparse. Chung et al. (2023) examined the influence of general and reading anxiety on Chinese reading in a sample of grade 7 to grade 9 adolescents with and without dyslexia in Hong Kong. Their results showed that reading anxiety significantly predicted reading comprehension after controlling for working memory and rapid digit naming. However, less is known about the cognitive-linguistic factors mediating the relationship between foreign language anxiety and L2 word reading, especially in young readers. To our knowledge, even fewer studies have been conducted on English reading in Chinese readers. Chow and colleagues (2017) examined the contribution of foreign language anxiety to English reading in a sample of grade 1 ESL Chinese students in Hong Kong. Their study, however, did not examine the role of cognitive-linguistic factors in the relationship between foreign language anxiety and word reading. With reference to the Component Model of Reading (Joshi & Aaron, 2000, 2012), the Active View of Reading (Duke & Cartwright, 2021), and the Socio-educational Model of Second Language Acquisition (SLA) (Gardner & MacIntyre, 1993), the present study aims to contribute to this limited body of literature by exploring the interplay between affective factors (foreign language reading and learning anxiety) and cognitive-linguistic factors (oral vocabulary and phonological awareness) in contributing to foreign language reading performance in a sample of early elementary-grade ESL Chinese students.

The component model of reading (CMR) posits that the interplay of cognitive factors (e.g., phonological awareness and orthographic knowledge), psychological factors (e.g., anxiety and motivation), and ecological factors (e.g., socioeconomic status and home learning environment) affects children’s literacy acquisition and difficulties in these domains result in reading difficulties (Aaron et al., 2008; Chiu et al., 2012; Joshi & Aaron, 2000). Notably, Aaron and colleagues (2008) suggested that learning English as a second language accounts for the variance of the ecological factor. A study examined the influences of these factors on L1 reading difficulties in 186,725 fourth graders across 38 countries using data from the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS; Chiu et al., 2012). Their results supported that the CMR’s cognitive, psychological, and ecological factors were significantly associated with L1 reading difficulties across different cultures and languages. The relationship between the cognitive factor and reading achievement has been evident in many studies (e.g., Aaron et al., 2008; Kearns & Al Ghanem, 2019; Li et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2017; Xie et al., 2022). Recent cross-sectional studies have shown a significant association between the psychological factor (i.e., anxiety) and L1 reading (Chung et al., 2023; Katzir et al., 2018). However, the influence of the psychological factor in L2, namely, foreign language anxiety (FLA), on L2 word reading has not been widely examined, especially among students at risk of learning difficulties. Therefore, this study aims to fill the literature gap by examining the relationship between FLA and English word reading in a group of ESL Chinese students at risk of learning difficulties.

The Active View of Reading also posits the potential influence of affective factors (e.g., motivation and anxiety) on reading beyond sublexical skills (e.g., phonological awareness and letter knowledge), language comprehension (e.g., syntactic knowledge and verbal reasoning), and bridging factors between them (e.g., vocabulary knowledge and morphological awareness) (Duke & Cartwright, 2021). Previous studies have examined some paths in the model, for example, the reading anxiety-vocabulary knowledge relationship (Macdonald et al., 2021) and the reading anxiety-word reading relationship (Katzir et al., 2018) in L1. This study provides empirical support to the Active View of Reading by examining the relationship between FLA and cognitive-linguistic skills (i.e., oral vocabulary and phonological awareness) in a group of Chinese ESL students at risk of learning difficulties.

Moreover, the Socio-educational Model of SLA posits that cultural experience and education levels influence affective factors that play significant roles in L2 reading performance (Gardner, 2019; Gardner & MacIntyre, 1993). Most previous studies have been conducted among college students in Western countries (e.g., Australia: Jee, 2019; Canada: Pichette, 2009; United Kingdom: Melchor-Couto, 2018; United States: Scida & Jones, 2017). However, research conducted in Asian regions like Hong Kong is limited, especially among elementary-grade students (Chow et al., 2017). Therefore, this study aims to examine the impact of FLA on early elementary-grade Chinese students in Hong Kong.

Foreign language learning anxiety

The role of anxiety in foreign language learning has received attention since the 1970s (e.g., Aida, 1994; Dörnyei, 2005; Horwitz, 1986; Horwitz et al., 1986; Scovel, 1978). Analysis of bibliometric studies on research trends in the past two decades showed that anxiety is one of the most frequently discussed individual differences variables in second language acquisition (Lei & Liu, 2018; Zhang, 2019a). Foreign language anxiety has been conceptualized as distinct from general anxiety (Aida, 1994; Horwitz et al., 1986; MacIntyre & Gardner, 1991, 1994) and personality trait anxiety and state anxiety (e.g., Dörnyei, 2005; Horwitz, 2001; Horwitz et al., 1986; MacIntyre, 1999; Scovel, 1978). Foreign language anxiety (FLA) is a situation-specific type of anxiety uniquely related to learning or using a second or foreign language (Horwitz et al., 1986; MacIntyre, 1999; MacIntyre & Gardner, 1999), which is commonly measured by the foreign language classroom anxiety scale (FLCAS; Horwitz et al., 1986) and the foreign language reading anxiety scale (FLRAS; Saito et al., 1999). Trait anxiety, state anxiety, and test anxiety are the three major types of anxiety that have been studied in the context of language learning (Francis et al., 2019). The underlying constructs of FLA proposed by researchers include fear or apprehension associated with speech/communication, negative evaluation, classroom performance, and test anxiety in foreign language learning contexts (Aida, 1994; Horwitz et al., 1986; Matsuda & Gobel, 2004).

Past studies have consistently shown the negative associations between FLA and second/foreign language learning across languages (e.g., Arabic, English, Japanese, French, English, German, and Spanish) and cultural backgrounds (Teimouri et al., 2019; Toyama & Yamazaki, 2021; Zhang, 2019b). An overall correlation of − 0.36 between FLA and language achievement was identified in a meta-analysis by Teimouri et al. (2019) on 97 reported studies from 23 countries. A similar overall strength of association between FLA and foreign language performance, r = -0.34, was found in a meta-analysis by Zhang (2019b). The results of the meta-analyses showed that the education level of students (Teimouri et al., 2019) instead of students’ proficiency level (Zhang, 2019b) was a significant moderator of the negative relationship between FLA and language performance. That is, elementary-grade students are more likely to be negatively affected by FLA than students in high schools/colleges. Although studies conducted among high school or college students, n = 88, far outnumbered those conducted among elementary-grade students, n = 3 (Teimouri et al., 2019).

Researchers (Sparks & Alamer, 2022; Sparks & Ganschow, 2007; Sparks & Patton, 2013; Sparks et al., 2018) argued for the unique role of FLA in L2 reading, however. They suggested that FLA, as measured by FLCAS and FLRAS, may be associated with L1 language skills rather than being unique to L2 language skills. Sparks and Ganschow (2007) examined the relationship between FLA, measured by FLCAS, and L1 and L2 literacy and language skills in a group of English-speaking primary school students in the US. The result found that FLCAS was significantly negatively associated with English literacy and language skills before learning a second language (i.e., French, German, and Spanish). Sparks et al. (2018) obtained a similar result: FLRAS was significantly associated with L1 skills in a group of high school students in the US who were learning Spanish as their second language. According to the Linguistic Coding Deficit Hypothesis (Sparks, 1995), difficulties in L1 language skills may hinder similar skills in L2. Because of the similar difficulties across L1 and L2, the L2 anxiety related to L2 language skills may also be related to the similar L1 language skills. However, the cross-cognitive-linguistic transfer from L1 to L2 could be weaker if L1 and L2 are in two writing systems, for example, Chinese and English (McBride-Chang et al., 2012) and Japanese and English (Wydell & Butterworth, 1999), although previous studies have examined the transfer of cross-language deficit in readers speaking languages from two writing systems (e.g., Chinese ESL readers: Chung & Ho, 2010; Korean ESL readers: Kim, 2008). Unlike English, the Chinese language is in a non-alphabetic writing system and is considered a morpho-syllabic language, making Chinese demands more on visual-orthographic and morphological skills and less on phonological skills (McBride-Chang et al., 2012). Researchers have found that poor L1 Chinese readers did not show the same deficit in their L2 English (McBride-Chang et al., 2012). Moreover, L1 Chinese cognitive-linguistic skills significantly predicted L2 English word reading but not vice-versa (Chung & Ho, 2010). However, studies examining the relationship between L2 English anxiety and L2 English reading in Chinese ESL readers are sparse (e.g., Chow et al., 2017), particularly in students at risk of learning difficulties. This study aims to fill this literature gap by examining the relationship between L2 anxiety and English reading in Chinese ESL students at risk of learning difficulties whose L1 and L2 were in two writing systems.

Two published studies have investigated FLA and language achievement in Chinese learners (Chow et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2021). A significant negative correlation between FLA and English language achievement was found in a sample of 631 grades 4 to 6 Chinese children from the Guangdong Province, China (Hu et al., 2021). Children’s English vocabulary knowledge and FLA were found to be significantly predicted by their mother-rated FLRA in a study among 48 first graders and their parents in Hong Kong (Chow et al., 2017). In their study, although children’s expressive vocabulary knowledge and FLRA were negatively correlated, r = -30, they did not examine the predictive relationship between the two constructs. Additionally, reading measures in English were not included in the study. Overall, little is known about the role of FLA and language development among young Chinese students, not to mention that students struggled in learning an L2.

Anxiety and reading difficulties

Research has shown that individuals with reading difficulties are more prone to anxiety problems (Carroll & Iles, 2006; Eissa, 2010; Grills-Taquechel et al., 2012; Jordan et al., 2014; Livingston et al., 2018; Mammarella et al., 2014; Zuppardo et al., 2021). Given the heavy emphasis on academic achievement in modern society, children with reading difficulties are likely to experience high levels of anxiety due to their repeated negative learning experiences and academic disadvantage (Francis et al., 2019; Novita, 2016). Although the literature on the relationships between anxiety and reading difficulties is extensive, there are still ongoing debates on the role of anxiety in educational and clinical settings (Novita, 2016). At the same time, anxiety may also affect the reading development of children with reading difficulties (Macdonald et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023). While the predictability of state anxiety on reading comprehension performance decreases as grade increases in typically developing readers, state anxiety consistently predicts reading comprehension performance among Chinese students with reading difficulties in grades 3 to 9 (Wang et al., 2023). In addition to general anxiety, Macdonald et al. (2021) also examined the role of reading anxiety in reading development in struggling students in grades 4 and 5. They found that although reading and general anxiety were closely related, r = 0.63, only the former, but not the latter, was significantly correlated with word reading and reading comprehension. These results highlight the unique role of situation-specific anxiety in reading development among struggling students. In particular, research has shown that students in countries/regions with a more robust collectivist culture (including Hong Kong) experience higher levels of FLA compared to those in countries/regions with a greater individualist culture (e.g., Australia, Canada, and the United States) (Toyama & Yamazaki, 2022). A more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the relationships between FLA and FL learning among young struggling students is needed to develop FL programs to equip young Chinese students better to overcome FLA. This study aims to contribute to this underexplored research area by examining the interrelationships between FLA and FL performance among ESL Chinese students at risk of English learning difficulties in grades 2 to 3.

Cognitive-linguistic skills important to English word reading in Chinese ESL students

Previous studies have consistently shown that phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge are cognitive-linguistic skills important to learning to read English words in ESL Chinese students (Chow et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2017; McBride-Chang & Ho, 2005; McBride-Chang & Kail, 2002; Xie et al., 2022; Yeung & Chan, 2013; Yeung, Ho, et al., 2013, Yeung, Siegel, et al., 2013). Phonological awareness significantly predicts English word reading and spelling among young ESL Chinese students (Chow et al., 2005; McBride-Chang & Ho, 2005; McBride-Chang & Kail, 2002; Yeung & Chan, 2013). For example, McBride-Chang and Kail (2002) investigated the predictors of Chinese and English word reading among kindergarten children in Hong Kong and the United States. Results showed that English and Chinese phonological awareness (assessed by a syllable deletion task) was the strongest predictor of English word reading among the variables investigated (i.e., speeded naming, visual-spatial skill, and processing speed). Instruction on phonological awareness skills effectively enhances English reading and spelling among Chinese ESL children in Hong Kong kindergarteners (Yeung, Siegel, et al., 2013). Yeung, Siegel, et al., (2013) also found that the change in phoneme deletion was a significant predictor of the change in English word reading in the instructional group, while the change in syllable deletion was a significant predictor of change in English word reading in the comparison group.

In addition to phonological awareness, children’s expressive vocabulary knowledge is another important predictor of English reading abilities in Chinese ESL students in recent studies (Liu et al., 2017; Xie et al., 2022; Yeung & Chan, 2013). In a study by Yeung and Chan (2013), phonological awareness and expressive vocabulary knowledge were significant predictors of English word reading after controlling for age and general intelligence in typically developing kindergarteners. After controlling for English phonological awareness and cognitive-linguistic skills, the initial level and growth rate of expressive vocabulary knowledge were significant longitudinal predictors of English word reading (Liu et al., 2017). A recent study among Chinese ESL students in grades 3 and 4 found that expressive vocabulary knowledge contributed to English reading comprehension through word reading and listening (Xie et al., 2022).

The present study

The present study has two research objectives. First, previous studies have examined the relationship between FLA and L2 word reading among typically developing Chinese children (Chow et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2021). The present study used a longitudinal research design to examine the prediction of FLA (i.e., parent-rated children’s foreign language reading anxiety and child-rated foreign language learning anxiety) to cognitive-linguistic skills and English word reading among ESL Chinese students at risk of English learning difficulties in Hong Kong to fill the gap in the literature about ESL students at risk of learning difficulties. Studies have shown significant predictions of parent-rated (Chow et al., 2017) and child-rated foreign language anxiety (Hu et al., 2021) on L2 word reading; thus, we expected that both parent-rated and child-rated foreign language anxiety would predict English word reading in this study. Second, we tested the mediating effect of two major cognitive-linguistic skills on the relationships between FLA and T2 English word reading among ESL Chinese students. We anticipated that expressive vocabulary knowledge and phonological awareness would mediate the relationship between FLA and English word reading.

Method

Participants

One hundred and seventy-seven grades 2 to 3 ESL Chinese students (Mage = 94.31 months, SDage = 8.43 months, female = 67) from 12 primary schools and their mothers participated in this study. The 12 schools were randomly recruited by sending invitation letters to all primary schools in Hong Kong. School teachers nominated students at risk of English learning difficulties to participate in this study using the Observation Checklist for Teachers (OCT), a standardized assessment tool under the Early Identification and Intervention Programme (EII: Hong Kong Education Bureau, 2013). The EII programme is implemented in all public sector primary schools in Hong Kong to support students with learning difficulties. The English learning subscale of the OCT checklist consisted of four items: (1) Able to read words and simple sentences after the teacher; (2) Able to write out simple sentences which the teacher dictates; (3) Able to comprehend simple verbal instructions; and (4) Able to describe pictures using simple words that rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Students rated below the 15th percentile in the OCT checklist were identified as at risk of English learning difficulties. All students in this study matched the identification criterion. In Hong Kong, students receive formal Chinese and English language instruction in kindergarten. English literacy skills in primary schools are taught by native English-speaking teachers to develop students’ fluent and accurate spoken and written English. All students in this study have had at least five years of exposure to English and were screened to have adequate learning opportunities in schools and without behavioral or emotional problems or uncorrected sensory impairments.

Procedures and materials

Students were assessed on their English reading abilities in 10-month intervals at the beginning and the end of the 2021/2022 academic year. Trained research assistants administered the assessment to individual students in a 60-min session. Students and their mothers were asked to complete the questionnaire about children’s English learning and reading anxiety. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents before proceeding with the study.

Parent-rated child foreign language reading anxiety (FLRA) This scale was adopted from the foreign language reading anxiety scale from the study of Chow et al. (2017). Mothers were asked to rate 20 items about their children’s English reading anxiety on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) at T1. Sample items include “When reading English, my child gets nervous and confused when (s)he does not understand every word” and “When reading English, my child often understands the words but still cannot quite understand what the author is saying.” All items were translated to Chinese and back-translated to English to ensure content validity. The total score was the sum of all responses, with a higher score indicating a higher level of anxiety. The possible maximum score was 100, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89.

Child-rated foreign language learning anxiety (FLLA) This scale was modified from the math anxiety questionnaire from Ramirez et al. (2016) study, consisting of eight items rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Students were asked to respond to this scale at T1. Sample items include “Do you feel nervous in an English class when you do not understand something?” and “Do you feel nervous when writing a birthday card in English?” All items were translated to Chinese and back-translated to English to ensure the content validity of the items. The total score was the sum of all responses, with a possible maximum score of 32, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.76.

English word reading. Modeled after the word reading task from Chung and Ho’s (2010) study, this task assessed students’ word decoding skills. This task was administered to students at T1 and T2. Students were required to read aloud a wordlist of 110 English words arranged in ascending order of difficulty one by one. These words were selected from English textbooks for grades 1 to 4 students in Hong Kong. One point was awarded for each correctly read word. The total scores were the sum of all correctly read words. The possible maximum score was 110, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.99.

Expressive vocabulary knowledge Modeled after the expressive vocabulary task from Chow et al. (2017) study, this task assessed students’ expressive vocabulary knowledge. This task was administered to students at T1. Students were required to name 28 black-and-white illustrations corresponding to 28 English vocabulary words, including 19 nouns, three verbs, and two adjectives. These words were selected from English textbooks for grades 1 to 4 students in Hong Kong. One point was awarded for each correct response regardless of plurality and tenses. The total scores were the sum of all correctly named English words. The possible maximum score was 28, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95.

Phonological awareness Modeled after the phoneme deletion task from Chung and Ho’s (2010) study, this task assessed students’ sensitivity to English syllables and phonemes. This task was administered to students at T1. This task consisted of 26 English words selected from English textbooks for grades 1 to 3 students in Hong Kong. For each trial, Students were asked to listen to an English word, for example, pilot, and repeat the word without a target syllable, /ˈpaɪ/, or phoneme, /t/. One point was awarded for each correct response. The total scores were the sum of correct responses. The possible maximum score was 26, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Working memory Modeled after the backward digit span task from Chung and Ho’s (2010) study. This task was conducted in Chinese and administered to students at T1. For each trial, students were asked to listen to a digit sequence and repeat the digits in reverse order. A total of 14 digit sequences were presented to students, and the number of digits was increased by one for every two sequences from two to eight digits. One point was awarded for each correctly repeated sequence. The total score was the sum of all correctly repeated sequences. The possible maximum score was 14, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77.

Data analysis

Two path analyses were conducted to examine the longitudinal prediction of T1 FLRA and FLLA on English word reading at T1 and T2 to address the first research question. Multiple fit indices determined model fits: χ2 test, comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR), and root mean square of approximation (RMSEA). A non-significant χ2 test value, CFI > 0.95, SRMR < 0.06, and RMSEA < 0.08, indicated an excellent fit to the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Moreover, mediation analysis using bias-corrected bootstrapping with 2,000 resamples was conducted to examine the mediating effects of cognitive-linguistic skills between FLA and English word reading at T1 and T2 to answer the second research question. The bootstrapping method is commonly used to enhance the power and reduce Type 1 errors in mediation analysis (Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Preacher et al., 2007).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis are presented in Table 1. The grade level was not significantly correlated with the T2 English word reading. Therefore, it was not included in further analyses. FLRA was significantly associated with T1 English word reading, r = -0.47, expressive vocabulary knowledge, r = -0.49, and phonological awareness, r = -0.21, and T2 English word reading, r = -0.46. FLLA was significantly associated with expressive vocabulary knowledge, r = -0.16, and phonological awareness, r = 0.19. T1 English word reading was significantly associated with expressive vocabulary knowledge, r = 0.67, phonological awareness, r = 0.41, and T2 English word reading, r = 0.88.

Path analysis

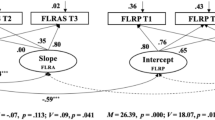

As shown in Fig. 1, we postulated FLRA and FLLA to have direct and indirect effects through T1 English word reading on T2 English word reading. This model shows an excellent fit to the data, χ2 (0) = 0.00, p > 0.05, CFI > 0.99, SRMR < 0.01, and RMSEA < 0.01. This result showed that FLRA but not FLLA was a significant predictor of T1 English word reading. Moreover, T1 English word reading significantly mediated the relationship between FLRA and T2 English word reading, β = − 0.40. Because these results showed FLLA was not a significant predictor of English word reading, the further analysis only examined the indirect effect between FLRA and English word reading.

We examined the mediating effect of cognitive-linguistic skills between FLRA and English word reading at T1 and T2. Figure 2 shows an excellent fit to the data, χ2 (0) = 0.00, p > 0.05, CFI > 0.99, SRMR < 0.01, and RMSEA < 0.01. This result suggested that FLRA was a significant predictor of concurrent cognitive-linguistic skills as well as English word reading after controlling for working memory. Table 2 shows the results of the mediation analysis. Expressive vocabulary knowledge, β = − 0.14, and T1 English word reading, β = − 0.12, significantly fully mediated the effect between FLRA and T2 English word reading. Although FLRA significantly predicted phonological awareness, phonological awareness was not a significant predictor nor mediator of T2 English word reading.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between FLA and English word reading in a sample of grades 2 to 3 Chinese students at risk of English learning difficulties in Hong Kong. Drawing on the Component Model of Reading (Aaron et al., 2008; Chiu et al., 2012; Joshi & Aaron, 2000) that affective factors (foreign language anxiety) influence cognitive-linguistic and literacy skills, we investigated the mediating effects of cognitive-linguistic skills between FLA and English word reading. The results partly supported the hypothesis that FLA significantly predicted English word reading. Only FLRA, but not FLLA, was a significant predictor of English word reading after controlling for working memory. Previous studies have shown that the role of FLA might be influenced by L1 skills (Sparks & Alamer, 2022; Sparks & Ganschow, 2007; Sparks & Patton, 2013; Sparks et al., 2018). Chow et al. (2017) found that FLA and L2 reading are significantly intercorrelated in typically developing ESL Chinese students. In line with these studies, our findings suggest that FLA plays an important role in L2 reading among Chinese students at risk of English learning difficulties where Chinese and English are in two different writing systems. Moreover, aligned to the Linguistic Coding Deficit Hypothesis (Sparks, 1995), ESL Chinese readers may not experience the same difficulties across Chinese and English, such that ESL Chinese perhaps display specific anxiety in learning English.

Surprisingly, our findings showed that only parent-rated children’s reading anxiety but not child-self-rated learning anxiety significantly predicted English word reading. No significant association, however, was found between child-rated reading anxiety, parent-rated reading anxiety, and English word reading in the present study. There are at least two explanations for this finding. First, English is not the major communication medium among Chinese children, and they might have learned minimal English reading; thus, they might not be aware of their reading and learning anxiety in English through daily communication. Researchers have shown that children begin to develop the concept of self-evaluation at five years old (Ruble et al., 1980; Stipek et al., 1992). Therefore, children in this study might not have an accurate self-report of their anxiety toward English learning. However, it is possible that children might show apprehension when reading English materials, for example, English textbooks and homework, and their mothers observed their reading anxiety during home literacy practices (Chow et al., 2017). Therefore, only FLRA, but not FLLA, was significantly associated with English word reading and cognitive-linguistic skills. Second, the insignificant finding might be related to the response scale. The child-rated reading anxiety scale was modified from the math anxiety scale from the Ramirez et al. (2016) study. The math anxiety scale used a sliding scale with three faces indicating the level of anxiety: calm face, semi-nervous face, and obviously nervous face. Instead of the sliding scale, a 4-point Likert scale was used in this study. It is possible that elementary-grade students might find it difficult to interpret the response on a Likert scale, and that might affect the results of FLLA. Future studies should consider using the sliding scale or a Harter scale (Harter, 1985) among elementary-grade students to understand the response scale better.

Mediating effect of cognitive-linguistic skills between foreign language anxiety and English word reading

Studies have examined the direct predictive relationship between reading anxiety and literacy skills in L1 and L2 (Chow et al., 2017; Macdonald et al., 2021). In addition to direct relationships between FLA and word reading, the present study also examined the indirect effect of FLA on English word reading through cognitive-linguistic skills after controlling for working memory. The findings were partially in line with our hypotheses. Only expressive vocabulary knowledge significantly fully mediated the relationship between FLA and T2 English word reading. Saito et al. (1999) proposed that L2 readers experience anxiety when they cannot comprehend the meaning of a text, suggesting that if L2 readers do not understand the vocabulary in an L2, it would increase their level of anxiety and influence their L2 word reading performance. In particular, Chinese and English are in two writing systems, such that difficulties in Chinese might not transfer to English learning. Therefore, ESL Chinese readers might feel specific anxiety when reading English texts. This specific anxiety might be more prominent due to the lack of cultural knowledge (Dewale et al., 2013; Saito et al., 1999) of English in elementary-grade Chinese children.

FLRA significantly predicted phonological awareness; however, phonological awareness was not a significant longitudinal predictor of English word reading, and the subsequent indirect effect was also insignificant. One possible explanation for this finding is that Chinese children have a similar brain process for reading Chinese and English words (Kim et al., 2017). Because of the morphosyllabic nature of the Chinese language, researchers have found phonological awareness to be the least significant concurrent and longitudinal predictor of Chinese word reading (Yeung et al., 2011; Yeung, Ho, et al., 2013). In a previous brain imaging study, Kim et al. (2017) found that Chinese readers showed activation in the lexical pathway instead of the sublexical pathway when reading English words, suggesting that phonological awareness might not be a significant factor in reading English words among Chinese readers. Future studies should consider examining the indirect effect of FLRA through other cognitive-linguistic skills, for example, morphological awareness and orthographic knowledge, to shed more light on the mediating role of cognitive-linguistic between FLA and L2 word reading.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations of this study are worth considering. First, although studies in FLA have used the Foreign Language Reading Anxiety Scale (FLRAS) and the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) to measure L2 reading anxiety across different languages (Chow et al., 2017; Horwitz et al., 1986; Saito et al., 1999), showing that FLRAS and FLCAS predicted L2 reading, the validity, reliability, and invariance of FLRAS and FLCAS may warrant further investigation to understand students’ L2 anxiety by using various psychometric testing procedures [for more discussion about the measurement of language anxiety, see Sparks and Alamer (2023)] and mixed methods research design. Second, studies in the US have shown that students’ L1 achievement may affect their L2 reading anxiety through L2 aptitude, L2 achievement, and cognitive-linguistic skills in L1 (Sparks & Alamer, 2022; Sparks & Ganschow, 2007). The relationships of L1 skills and achievement with L2 reading anxiety, skills, and literacy development in Chinese students may be worth examining over time. Third, future studies may examine the role of individual differences in language aptitude, especially L2 aptitude, and their relationships with L1 skills before exposure to L2 and during the development of L2. Fourth, further research can be done to investigate whether the state and trait anxiety levels of students are present and whether they are likely to link with L2 anxiety and L1 and L2 acquisition. Fifth, future studies may examine students’ state and trait anxiety by measuring physiological responses, such as heart and respiratory rate, which is more objective than self-reported data (Daley et al., 2014). Finally, the present study only included phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge as the mediators and English word reading as the dependent variable. Future work may examine FLA’s direct and indirect effects on literacy outcomes, such as word spelling and reading comprehension, through cognitive-linguistic skills, such as morphological awareness and orthographic knowledge.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations of this study, its findings have important implications for research and practice. This study filled the literature gap on the role of FLA in foreign language learning among students who struggled to learn an L2. In addition to cognitive-linguistic skills, affective factors are important predictors of language learning outcomes of students at risk of English learning difficulties. The results also shed more light on the literature about the role of FLA on L2 achievement in Hong Kong society with a collectivist culture, suggesting the generalizability of the significance of FLA in second/foreign language learning across cultures. Moreover, it is plausible that FLA influences later literacy skills through early literacy skills and cognitive-linguistic skills. More research should be directed to the mechanism underlying the influence of FLA on literacy development.

The findings of this study have two major practical implications. First, mothers’ perception of their children’s FLA significantly indicates children’s foreign language reading performance. Therefore, communities and schools should promote mothers’ involvement in their children’s foreign language learning and may develop interventions to support the parents in establishing and maintaining a safe and supportive L2 learning environment. Second, as FLA is a plausible burden for students to learn an L2, educational practitioners consider designing, for example, play-based English learning curricula to soothe the learning anxiety children face in English language lessons and improve children’s English reading abilities. In sum, this study generalized the findings that FLA plays a significant role in foreign language learning for students at risk of English learning difficulties, and it also informs practitioners in designing foreign language curricula and activities to support students learning L2.

References

Aaron, P. G., Joshi, R. M., Gooden, R., & Bentum, K. E. (2008). Diagnosis and treatment of reading disabilities based on the component model of reading: An alternative to the discrepancy model of LD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219407310838

Aida, Y. (1994). Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope’s construct of foreign language anxiety: The case of students of Japanese. The Modern Language Journal, 78(2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02026.x

Carroll, J., & Iles, J. (2006). An assessment of anxiety levels in dyslexic students in higher education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(3), 651–662.

Chiu, M. M., McBride-Chang, C., & Liu, D. (2012). Ecological, psychological, and cognitive components of reading difficulties: Testing the component model of reading in fourth grades across 38 countries. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45, 391–405.

Chow, B. W.-Y., Chui, B. H.-T., Lai, M. W.-C., & Kwok, S. Y. C. L. (2017). Differential influences of parental home literacy practices and anxiety in English as a foreign language on Chinese children’s English development. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(6), 625–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1062468

Chow, B.W.-Y., McBride-Chang, C., & Burgess, S. (2005). Phonological processing skills and early reading abilities in Hong Kong Chinese kindergarteners learning to read English as a second language. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.1.81

Chung, K. K. H., Lam, C. B., Chan, K. S.-C., Lee, A. S. Y., Liu, C., & Wang, L.-C. (2023). Are general anxiety, reading anxiety, and reading self-concept linked to reading skills among Chinese adolescents with and without dyslexia? Journal of Learning Disabilities. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194231181914

Chung, K. K. H., & Ho, C. S.-H. (2010). Second language learning difficulties in Chinese dyslexic children: What are the reading-related cognitive skills that contribute to English and Chinese word reading? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43(3), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219409345018

Daley, S. G., Willett, J. B., & Fischer, K. W. (2014). Emotional responses during reading: Physiological responses predict real-time reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033408

Dewaele, J.-M., & Ip, T. S. (2013). The link between foreign language classroom anxiety, second language tolerance of ambiguity and self-rated English proficiency among Chinese learners. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 3(1), 47–66.

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.411

Eissa, M. (2010). Behavioral and emotional problems associated with dyslexia in adolescence. Current Psychiatry, 17(1), 17–25.

Francis, D. A., Caruana, N., Hudson, J. L., & McArthur, G. M. (2019). The association between poor reading and internalising problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 67, 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.09.002

Gardner, R. C. (2019). The socio-educational model of second language acquisition. In M. Lamb, K. Csizer, A. Henry, & S. Ryan (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 21–37). Palgrave Macmillan.

Gardner, R., & MacIntyre, P. (1993). A student’s contributions to second-language learning. Part II: Affective variables. Language Teaching, 26(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800000045

Grills-Taquechel, A. E., Fletcher, J. M., Vaughn, S. R., & Stuebing, K. K. (2012). Anxiety and reading difficulties in early elementary school: Evidence for unidirectional- or bi-directional relations? Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 43(1), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-011-0246-1

Harter, S. (1985). Manual for the self-perception profile for children. University of Denver Press.

Hong Kong Education Bureau (2013). Observation checklist for teachers (Short version). Hong Kong Education Bureau.

Horwitz, E. (1986). Preliminary evidence for the reliability and validity of a foreign language anxiety scale. TESOL Quarterly, 20, 559–562. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586302

Horwitz, E. K. (2001). Language anxiety and achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 112–126.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.2307/327317

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, X., Zhang, X., & McGeown, S. (2021). Foreign language anxiety and achievement: A study of primary school students learning English in China. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211032332

Jee, M. J. (2019). Foreign language anxiety and self-efficacy: Intermediate Korean as a foreign language learners. Language Research, 55(2), 431–456. https://doi.org/10.30961/lr.2019.55.2.431

Jordan, J., McGladdery, G., & Dyer, K. (2014). Dyslexia in higher education: Implications for maths anxiety, statistics anxiety, and psychological well-being. Dyslexia, 20(3), 225–240.

Joshi, R. M., & Aaron, P. G. (2000). The component model of reading: Simple view of reading made a little more complex. Reading Psychology, 21(2), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710050084428

Joshi, R. M., & Aaron, P. G. (2012). Componential model of reading (CMR): Validation studies. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(5), 387–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219411431240

Katzir, T., Kim, Y. G., & Dotan, S. (2018). Reading self-concept and reading anxiety in second grade children: The roles of word reading, emergent literacy skills, working memory and gender. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01180

Kearns, D. M., & Al Ghanem, R. (2019). The role of semantic information in children’s word reading: Does meaning affect readers’ ability to say polysyllabic words aloud? Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(6), 933–956. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000316

Kim, S. Y., Liu, L., & Cao, F. (2017). How does first language (L1) influence second language (L2) reading in the brain? Evidence from Korean-English and Chinese-English bilinguals. Brain and Language, 171, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2017.04.003

Kim, Y. S. (2008). Crosslinguistic influence on phonological awareness for Korean-English bilingual children. Reading and Writing, 22(7), 843–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-008-9132-z

Lei, L., & Liu, D. (2018). Research trends in applied linguistics from 2005 to 2016: A bibliometric analysis and its implications. Applied Linguistic, 40(3), 540–561. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amy003

Li, M., Koh, P. W., Geva, E., Joshi, R. M., & Chen, X. (2020). The componential model of reading in bilingual learners. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(8), 1532–1545. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000459

Liu, Y., Yeung, S. S., Lin, D., & Wong, R. K. S. (2017). English expressive vocabulary growth and its unique role in predicting English word reading: A longitudinal study involving Hong Kong Chinese ESL children. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.02.001

Livingston, E. M., Siegel, L. S., & Ribary, U. (2018). Developmental dyslexia: Emotional impact and consequences. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 23(2), 107–135.

Macdonald, K. T., Cirino, P. T., Miciak, J., & Grills, A. E. (2021). The role of reading anxiety among struggling readers in fourth and fifth grade. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 37(4), 382–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2021.1874580

MacIntyre, P. D. (1999). Language anxiety: A review of the research for language teachers. In D. J. Young (Ed.), Affect in foreign language and second language learning: A practical guide to creating a low anxiety classroom atmosphere (pp. 24–25). McGraw-Hill.

MacIntyre, P. D., & Gardner, R. C. (1991). Language anxiety: Its relationship to other anxieties and to processing in native and second languages. Language Learning, 41(4), 513–534.

MacIntyre, P. D., & Gardner, R. C. (1994). The subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing in the second language. Language Learning, 44, 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01103.x

Mammarella, I., Ghisi, M., Bomba, M., Bottesi, G., Caviola, S., Broggi, F., & Nacinovich, R. (2014). Anxiety and depression in children with nonverbal learning disabilities, reading disabilities, or typical development. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 49(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219414529336

Matsuda, S., & Gobel, P. (2004). Anxiety and predictors of performance in the foreign language classroom. System, 32, 21–36.

McBride-Chang, C., & Ho, C. S.-H. (2005). Predictors of beginning reading in Chinese and English: A 2-year longitudinal study of Chinese kindergarteners. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 117–144. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_2

McBride-Chang, C., & Kail, R. V. (2002). Cross-cultural similarities in the predictors of reading acquisition. Child Development, 73(5), 1392–1407. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00479

McBride-Chang, C., Liu, P. D., Wong, T., Wong, A., & Shu, H. (2012). Specific reading difficulties in Chinese, English, or both: Longitudinal markers of phonological awareness, morphological awareness, and RAN in Hong Kong Chinese children. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(6), 503–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219411400748

Melchor-Couto, S. (2018). Virtual word anonymity and foreign language oral interaction. ReCALL, 30(2), 232–249. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344017000398

Novita, S. (2016). Secondary symptoms of dyslexia: A comparison of self-esteem and anxiety profiles of children with and without dyslexia. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 31(2), 279–288.

Pichette, F. (2009). Second language anxiety and distance language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 42(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2009.01009.x

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Ramirez, G., Chang, H., Maloney, E. A., Levine, S. C., & Beilock, S. L. (2016). On the relationship between math anxiety and math achievement in early elementary school: The role of problem solving strategies. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 141, 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2015.07.014

Ruble, D. N., Boggiano, A. K., Feldman, N. S., & Loebl, J. H. (1980). Developmental analysis of the role of social comparison in self-evaluation. Developmental Psychology, 16(2), 105–115.

Saito, Y., Garza, T. J., & Horwttz, E. K. (1999). Foreign language reading anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 83(2), 202–218.

Scida, E. E., & Jones, J. E. (2017). The impact of contemplative practices on foreign language anxiety and learning. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 7(4), 573–599. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2017.7.4.2

Scovel, T. (1978). The effect of affect on foreign language learning: A review of the anxiety research. Language Learning, 28(1), 129–142.

Sparks, R. L., & Alamer, A. (2022). Long-term impacts of L1 language skills on L2 anxiety: The mediating role of language aptitude and L2 achievement. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221104392

Sparks, R. L. (1995). Examining the linguistic coding differences hypothesis to explain individual differences in foreign language learning. Annals of Dyslexia, 45, 187–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02648218

Sparks, R. L., & Alamer, A. (2023). How does first language achievement impact second language reading anxiety? Exploration of mediator variables. Reading and Writing, 36(10), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10410-2

Sparks, R. L., & Ganschow, L. (2007). Is the foreign language classroom anxiety scale (FLCAS) measuring anxiety or language skills? Foreign Language Annals, 40(2), 260–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2007.tb03201.x

Sparks, R. L., & Patton, J. (2013). Relationship of L1 skills and L2 aptitude to L2 anxiety on the foreign language classroom anxiety scale. Language Learning, 63(4), 870–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12025

Sparks, R. L., Patton, J., & Luebbers, J. (2018). L2 anxiety and the foreign language reading anxiety scale: Listening to the evidence. Foreign Language Annals, 51, 738–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12361

Stipek, D., Recchia, S., McClintic, S., & Lewis, M. (1992). Self-evaluation in Young Children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 57(1), 1–98.

Teimouri, Y., Goetze, J., & Plonsky, L. (2019). Second language anxiety and achievement: A meta-analysis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 41(2), 363–387. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263118000311

Toyama, M., & Yamazaki, Y. (2022). Foreign language anxiety and individualism-collectivism culture: A top-down approach for a country/regional-level analysis. SAGE Open, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211069143

Wang, L. C., Chen, J. K., & Poon, K. (2023). Relationships between state anxiety and reading comprehension of Chinese students with and without dyslexia: A cross-sectional design. Learning Disability Quarterly, 46(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/07319487221149413

Wydell, T. N., & Butterworth, B. (1999). A case study of an English-Japanese bilingual with monolingual dyslexia. Cognition, 70, 273–305.

Xie, Q., Cai, Y., & Yeung, S. S. (2022). How does word knowledge facilitate reading comprehension in a second language? A longitudinal study in Chinese primary school children learning English. Reading and Writing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10360-9

Yeung, P.-S., Ho, C. S.-H., Chan, D. W., Chung, K. K. H., & Wong, Y.-K. (2013). A model of reading comprehension in Chinese elementary school children. Learning and Individual Differences, 25, 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.03.004

Yeung, P.-S., Ho, C. S.-H., Chik, P. P., Lo, L. Y., Luan, H., Chan, D. W., & Chung, K. K. H. (2011). Reading and spelling Chinese among beginning readers: What skills make a difference? Scientific Studies of Reading, 15(4), 285–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2010.482149

Yeung, S. S., & Chan, C. K. K. (2013). Phonological awareness and oral language proficiency in learning to read English among Chinese kindergarten children in Hong Kong. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83, 550–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02082.x

Yeung, S. S. S., Siegel, L. S., & Chan, C. K. K. (2013). Effects of a phonological awareness program on English reading and spelling among Hong Kong Chinese ESL children. Reading and Writing, 26(5), 681–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-012-9383-6

Zhang, X. (2019a). A bibliometric analysis of second language acquisition between 1997 and 2018. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(1), 199–222. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263119000573

Zhang, X. (2019b). Foreign language anxiety and foreign language performance: A meta-analysis. The Modern Language Journal, 103(4), 763–781. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12590

Zuppardo, L., Serrano, F., Pirrone, C., & Rodriguez-Fuentes, A. (2021). More than words: Anxiety, self-esteem and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with dyslexia. Learning Disability Quarterly, 46(2), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/07319487211041103

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust—The Jockey Club Project RISE to Kevin Kien Hoa Chung. We also thank all teachers, students and research assistants for their participation.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Education University of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, K., Yeung, Ps. & Chung, K.K.H. The effects of foreign language anxiety on English word reading among Chinese students at risk of English learning difficulties. Read Writ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-024-10513-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-024-10513-y