Abstract

This study describes the initial implementation of the writing component of the Write to Read (W2R) literacy intervention in eight low-SES (socio-economically disadvantaged) elementary-level urban schools. Through customised onsite professional development provided by coaches, the writing component sought to build teachers’ capacity to design and implement a writing workshop framework infused with research-informed practices for writing suitable for their school and classroom contexts, including attention to cognitive, social and affective dimensions. The paper draws on quantitative and qualitative questionnaire data gathered from classroom teachers in the eight schools in Year 1 (n = 66) and Year 3 (n = 62) of implementation, and semi-structured interviews with randomly selected teachers in each school in Year 4 (n = 18). In general, teachers succeeded in implementing a writing workshop approach to teaching writing, within the broader W2R literacy framework, including the allocation of more time to writing instruction. Professional development, including observation, feedback and demonstration by W2R literacy coaches, contributed to high levels of teacher confidence in such areas as planning and teaching fiction and non-fiction writing genres, and analysing writing samples to inform mini-lessons. By Year 3, teachers noted marked or good improvements in students’ attitudes towards writing, volume of writing produced, knowledge of writing genres, and language of response to writing. Areas in need of further support included aspects of the craft of writing, including writing vocabulary, supporting pupils to set goals for writing, selecting mentor texts to teach writing genres, and using a rubric to assess writing development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The act of writing is a fundamental human activity critical to success in school and in realising potential in adult life. It plays a key role in supporting development in oral language and reading (Graham et al., 2018; Dockrell et al., 2015) and in learning across multiple disciplines (Graham et al., 2020). This paper reports on the writing dimension of Write to Read (W2R), a longitudinal school university research-practice partnership which investigates how best to support low-income schools in adopting research-informed approaches to literacy instruction that motivate and engage children as readers, writers and thinkers (Kennedy & Shiel, 2022; Kennedy, 2014) and also address the well-documented underachievement of children in such schools. Despite consistently strong overall performance on international literacy assessments in the last decade (e.g., Delaney et al., 2023), national assessment data in Ireland show persistent gaps in performance between students in low-income schools, and those in other schools (Nelis & Gilleece, 2023). Moreover, this situation continues even though there has been a sustained policy focus at national level to bridge such gaps (Department of Education and Science, 2005; Department of Education and Skills, 2017).

We begin by providing a synthesis of the research underpinning the conceptual framework adopted in our study. It is organised across 4 themes: theoretical perspectives on the writing process; teacher knowledge for writing; instructional frameworks; and professional development to support teacher learning. Following this, the methodology underpinning the study is outlined, and key findings are presented.

Conceptual framework

Perspectives on the Writing Process

Early theoretical models of the writing process (e.g., Hayes & Flower, 1980; Berninger & Swanson, 1994) highlight cognitive dimensions (e.g., the roles of working and long-term memory, metacognition) and pay some attention to affective dimensions (attitude, motivation, engagement, self-efficacy, self-regulation, value) which influence each stage of the writing process (planning, translating, revising). More recently, Graham’s (2018) revised Writer-in-Community Model has expanded on the cognitive and affective dimensions, promoting writing not just as a solitary act but a social one shaped by socio-cultural, historical and political contexts. Alongside the cognitive resources and executive control of the writer, the model highlights the multifaceted nature of writing beliefs such as motivation, engagement, attitudes and sense of self-efficacy.

Sense of self-efficacy is important for writing development as it determines whether an individual will undertake to write in the first instance, the level of effort exerted and the degree to which they will persist in the face of difficulty (Bruning & Kaufman, 2016). Schunk and Zimmerman (2007) argue that self-efficacy in writing is not merely an outcome of writing successfully, but a consequence of how well writers self-regulate and monitor how they are managing the writing process. De Smedt et al. (2017) have shown how self-efficacy for ideation, regulation and conventions can impact on cognitive aspects of writing (thinking, planning, revision and control strategies), and ultimately impact on the quality of narrative writing.

Self-regulation concerns self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions designed to affect one’s learning of knowledge and skills (Zimmerman, 2000). Self-regulation supports writers in a multiplicity of ways, enabling them to ‘attain greater awareness of their writing strengths and limitations and consequently be more strategic in their attempts to accomplish writing tasks’ (Troia et al., 2009, p. 99).

Berninger and Swanson (1994) note the role of metacognition in managing the interaction or co-ordination between writing processes. They describe metacognition as referring to writers’ understanding of the writing process (declarative information) and their knowledge of procedures for planning, composing and evaluating/revising texts (procedural knowledge). A notable omission from the model is reference to the conditional level (knowing why a strategy is useful) which, arguably, is critical if writers are to value and internalise the strategies and know when to use them (Paris, 2005). The development of metacognition can be emphasised in the course of self-regulated strategy development (SRSD, Graham et al., 2012).

Camacho et al.’s (2021) systematic review of writing motivation in schools between 2000 and 2018 found a moderate association between student motivation and performance measures. They also found that students’ writing motivation was associated with teaching practices such as SRSD instruction and the provision of opportunities for collaborative writing between peers and teachers.

Writing is clearly a complex multidimensional process encompassing cognitive, motivational, social and affective dimensions and as such requires high levels of ‘content knowledge’ and ‘pedagogical content knowledge (PCK)’ on the part of teachers (Shulman, 1987).

Teacher knowledge for writing

Myhill et al. (2023) identified just seven studies that focused on content knowledge for teaching writing. Among the key aspects identified in these studies were meaningful experiences as writers, with teachers learning how to be effective teachers of writing after engaging in writing themselves; subject knowledge of narrative writing; explicit understanding of rhetorical structures for writing; and some understanding of revising and editing, the characteristics of texts and different written genres.

Based on the literature on writing development as well as some policy statements, it can be argued that teachers’ content knowledge for writing should also include:

-

Stages or phases of writing development (e.g., Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1978);

-

The roles of working memory and long-term memory in writing (Graham, 2018);

-

How creative and literary texts and aesthetic genres are formed (NCTE, 2016);

-

Writing craft and technique (Kennedy & Shiel, 2019);

-

How spelling, grammar and punctuation develop and can be supported to improve writing (e.g., Myhill et al., 2012);

-

Why self-efficacy, self-regulation and metacognition are important for success in writing (Graham, 2018);

-

How students establish their identities as writers (Myhill et al., 2023);

-

The environments and communities in which writing takes place (Graham, 2018);

-

Links between reading and writing and how they can be mutually supportive (e.g., reading mentor texts to develop writing techniques across genres and disciplines) (Graham, 2020);

-

Key dimensions of the formative assessment of writing (Kennedy & Shiel, 2022);

-

The potential of digital environments to support writing development as new modalities, audiences and purposes for writing emerge (NCTE, 2016).

Instructional frameworks to support communities of writers

There is a broad body of research available on effective approaches to teaching writing, which should form part of teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge. Graves (1983), a pioneer of processed-based writing, advised that instructional time be allocated to writing in primary schools on at least four days per week. In a report for the US What Works Clearing House, Graham et al. (2012) identified the allocation of daily time for writing as important despite a limited research base. Graham et al. suggested 30 min per day in kindergarten and one hour in grades 1–6, with 50% of time allocated to teaching a range of writing strategies, techniques and skills appropriate to students’ levels, and 50% to writing practice, where students apply the skills they have learned. Gadd and Parr (2017) described effective teachers of writing as those who provide time and opportunities for students to write on self-selected topics and to write outside official instructional time.

There is a stronger research base to support the use of process-based approaches to writing instruction. Summarising this research, Slavin et al. (2019) noted that writing process models give students extended opportunities to write, and often include writing teams in which students help each other on various aspects of the writing process. They identified SRSD (Graham et al., 2012) and Writing Wings (Madden, 2011) as successful instructional models. Key features of SRSD include teaching students both general and task-specific writing strategies, the necessary background knowledge to use them, and procedures for regulating the strategies (e.g., goal setting, self-monitoring, self-instructions, and self-reinforcement), writing process and writing behaviours (Graham et al., 2012). Writing Wings involves students working in writing teams to help each other through writing process activities in different genres, with teacher modelling a key element. Drawing on studies published since 2011, Slavin et al. (2019) reported an effect size of 0.17 for process-based approaches to writing instruction in their systematic review – similar in strength to the effect sizes they reported for other writing interventions, including co-operative learning and programmes focusing on interactions between reading and writing.

The writing process is often implemented via the writing workshop (e.g., Calkins, 1986). Writing workshops typically include: (a) daily mini-lessons focussed on the craft, process and skills of writing; (b) daily time for students to write independently on self-selected topics during which time teachers conference with children and provide feedback as children are engaged in the act of writing; (c) and a daily share session in which children share their writing with peers and teacher. The writing workshop framework, which is often implemented in conjunction with relevant professional development for teachers, is consistent with research-based approaches to process writing, which provide instruction in specific aspects of writing as well as opportunities for continuous reading and writing. Moreover, it has been shown to have positive effects on writing performance in schools in which it has been implemented, albeit from the second year of implementation onwards, with cumulative effects observed over time (AIR, 2021). However, Troia et al. (2009) have pointed to variability in the ways in which writing workshop instruction is implemented as teachers work with high- and low-achieving writers. They found that teachers tended to allocate insufficient attention and specificity to goal setting and feedback when working with lower-achieving writers, and provided fewer opportunities for developing student agency and collaboration.

Teacher professional development

Research highlights the importance of attending to core and structural dimensions of professional development (Desimone & Garet, 2015). Core features include an emphasis on: (a) key content and pedagogical content strategies; (b) active learning and a social constructivist approach to knowledge building; and (c) coherence and alignment with national curricula and school goals. Structural features include the particular form of the professional development, its duration and intensity and the nature of the participation envisaged. A number of studies have suggested that, where significant changes in practice are required, whole-school professional development is more effective than that focused on individual teachers conducted off-site in isolation from the daily realities that teachers face in their classrooms (Kennedy, 2018; Au, 2005). Whole school approaches view professional development as a process of culture building and empowerment of teachers as professionals (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009). Similarly, in a study exploring features of effective schools in literacy, Lipson et al. (2004) contended that the ‘critical characteristics of the schools and teachers (successful ones) appear to include a strong sense of professional community coupled with strong support for individual professional decision-making and a focus on problem-solving’ (p. 539). Additionally, a key to successful whole school onsite professional development is provision of time and space for teachers to meet outside of the professional development sessions to consider implications and plan forward (Cordingley et al., 2015). It should be acknowledged that teacher learning is complex, situated and non-linear (King et al., 2022).

Overall, findings highlight the process of professional development as being as important as the content and pedagogies. Professional development should also consider the effect of change on teachers’ emotions (fear, anxiety, motivation, excitement, expectations), promote social involvement and include mastery, vicarious and social persuasion experiences to enhance teacher self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997), impact on attitudes, beliefs, and values (Liou & Canrinus, 2020; King et al., 2022) and empower teachers as professionals (Kennedy & Shiel, 2010).

Methodology

Overview of the Write to Read intervention

Over a four-year period, teachers of pupils in Pre-K-6th grades (4–12-year-olds) in eight urban schools with low socio-economic status (known as ‘disadvantaged’ or DEIS schoolsFootnote 1) participated in the Write to Read (W2R) project, a collaborative longitudinal university-school literacy intervention. It is conceptualised primarily as a ‘tier 1’ classroom intervention’ (Swanson et al., 2017) designed to enhance the quality of classroom literacy instruction across grade levels and to build progression year on year, with some ‘tier 2’ elements incorporated (e.g., teacher collaboration for small group instruction for children requiring additional support). W2R aims to enhance children’s motivation and engagement and literacy achievement within the context of a research-informed balanced literacy framework. The writing component involved the design and implementation of a writing workshop model for the Irish context.

Prior to the implementation of W2R, schools employed a largely traditional approach to teaching writing. Writing skills (e.g., grammar, punctuation) were generally taught in the context of workbooks with writing taught once a week, and some attention allocated to genre writing. Writing in the early years (Pre-K/K) predominantly involved handwriting and copying rather than an emphasis on the authorial dimensions of writing.

In line with research (e.g., King et al., 2022), PD in W2R includes a strong literacy content and pedagogical content knowledge focus, active learning as teachers adopt an inquiry stance to teaching and experiment with new approaches, attention to teachers’ and children’s needs following an analysis of strengths and challenges, alignment with the national curriculum, and whole school participation to build progression and coherence. PD offered is primarily onsite, is sustained over a number of years and includes access to a literacy coach with experience of teaching in low-income schools who supports teachers in designing and implementing an evidence-based balanced literacy framework suitable for their school context (Kennedy, 2014, 2018).

As such, W2R is not a programme; rather, it provides customised support to schools. Gradually, taking a phased approach, schools design and implement a 90-minute evidence-based comprehensive, integrated approach to literacy instruction that gives due attention to cognitive, aesthetic and affective dimensions (motivation, engagement, self-efficacy) of literacy, including writing.

In our study, over the four years, coaches worked with teachers to develop their content and pedagogical content knowledge about writing. The support they provided included an emphasis on each of the aspects of teacher content knowledge for writing outlined above, though there was less emphasis on the roles of working memory and long-term memory in writing, and on the potential of digital environments to facilitate writing development, than on other aspects. With regard to pedagogical content knowledge, support was provided on teaching a range of genres and developing mini-lessons specific to each, based on formative assessment of children’s writing. Schools were encouraged to build a framework that ensured children had opportunities to write on a daily basis, with each genre visited each year to build progress in writing across the school. Furthermore, to build children’s motivation, engagement and agency, teachers were asked to afford children control over writing topics within a genre and the amount of time they spent on a draft.

Implementation of the framework was cumulative and included all class levels in a school. In Phase 1 of Year 1, for example, there was an emphasis on shared/interactive writing in early years classes, writing workshop, share sessions, report and procedural writing genres and classroom conditions for fostering motivation in writing. Over time, additional writing genres and assessment tools were added (e.g., persuasive writing and poetry: Year 2; assessment rubrics: Year 3). After Year 2, coaches attended schools less often, as schools were encouraged to draw more heavily on their own resources to embed the framework.

Research questions

Research questions explored in the current study are:

-

1.

What conditions, resources and kinds of professional development supported teachers in low-income schools in changing their current classroom practice for writing to a research-informed writing workshop approach?

-

2.

How did teachers view the implementation of the writing component of the W2R framework and how did their views evolve over time?

Participants and research design

A purposive sample of eight elementary schools was involved in the initial implementation of the W2R intervention and in the current study. Seven schools were categorised by the Department of Education as DEIS Band 1 (among the most disadvantaged schools in the country) and the eighth was in Band 2. Schools were invited or requested to participate in W2R, either independently, or as part of a cluster (a group of geographically-close schools). The Band 2 school was part of one such cluster. All were located in a large city, in areas undergoing re-generation. In Years 1 and 3, all classroom teachers were invited to complete a teacher questionnaire. In Year 4, teachers in each school were selected at random for interview.

Measures

In this study, questionnaires and interviews were analyzed to examine the initial implementation of the writing component of W2R and teachers’ perceptions of its impact.

Teacher questionnaires

Teacher questionnaires were administered early in the second term across all class levels (Pre-K- Grade 6) in the 8 schools in Years 1 and 3. The questionnaires sought information on time allocation, pedagogies, assessment practices, teachers’ perceptions of pupils’ engagement and motivation, and teachers’ own confidence in designing and implementing a writing workshop, using four-point Likert-type rating scales. Information on aspects of writing that had improved under W2R was also sought and teachers were invited to comment on specific issues, including their views on implementation. Sixty-six teachers across the 8 schools completed the Teacher Questionnaire in Year 1, yielding a response rate of 90.4% (66/73), while 62 of 74 (83.7%) did so in Year 3. In both years, the teachers were fairly evenly distributed across Grades Pre-K to 6, with the highest percentages in both years in Grade 3 (16.7% in Year 1, and 16.1% in Year 3), though teachers rarely moved with the same class of students across years. In Year 1, 89.4% identified themselves as females. This dropped to 82.3% in Year 3. In Year 1, 18.5% of teachers reported that they had 1–4 years of teaching experience, 73.2% reported 5–12 years, and 9.1% reported 13 years or more. In Year 3, the corresponding percentages were 27.4%, 51.6% and 21% respectively. In Year 3, 72.9% of teachers reported that they had participated in W2R since Year 1. Reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) for different clusters of questionnaire items ranged from 0.73 (Ease of implementing W2R, Year 1) to 0.86 (Perceptions of pupils’ progress, Year 3).

Teacher interviews

Towards the end of Year 4, in each of the eight schools, teachers were randomly selected to participate in an interview to ascertain how the project was working across a school and to gain a more nuanced understanding of teachers’ classroom practices across grade levels in relation to writing instruction, their sense of self-efficacy for teaching writing and their perceptions of changes to children’s engagement and the quality of writing. Eighteen teachers agreed to be interviewed. Interviews were conducted by a researcher external to the project and were audiotaped to facilitate analysis. Eight of the teachers had been teaching in their school since the outset of the project and another had arrived in her school in Year 2. Of the remaining nine, five were new to their school in Year 3 with a further four in Year 4. In terms of experience, two of the 18 were newly qualified, three had less than five years’ experience, 9 had between 6 and 12 years’ experience and the remainder (4) had 13 + years.

Approaches to analysis

As noted above, the Teacher Questionnaires comprised both objective questions and comments from teachers on a range of implementation issues. Objective questions were analysed by computing descriptive statistics (e.g., mean scores, frequencies). The statistical significance of differences across years was not examined, due to attrition among teachers over time (with 60% of Year 1 teachers providing data again in Year 3).

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using Glaser and Strauss’ (1967) ‘constant comparative method’. Two interviews from two different schools were randomly selected for initial analysis and independently coded by two researchers. Codes were then compared and categories developed. Thereafter, interviews were coded by the first author. This resulted in 9 categories and 45 subcategories (Appendix, Table A1) which were combined into the 6 themes presented below. Qualitative data in the questionnaires were analysed using the same procedures as for teacher interviews.

Findings

Implementing the writing component of Write to Read in classrooms

The outcomes of the teacher questionnaire are considered under the following subheadings: ease of implementing W2R; confidence in implementing various aspects of W2R; perceived impact of W2R on children’s writing; and the impact of professional development. The subsections that follow provide a combination of data based on objective items, and, where available, teachers’ written comments on the questionnaires.

Perceptions of teachers on ease of implementing writing components of W2R

Teachers in Years 1 and 3 responded to a series of questions about the ease with which they implemented various aspects of writing in W2R (Table 1).

In Year 1 and Year 3, similar percentages of teachers (76.5%, 75.8% respectively) reported that they found teaching mini-lessons on writing skills such as grammar and punctuation to be very easy or easy. On the other hand, teachers reported that teaching mini-lessons on the craft of writing (e.g., expression, ideas, voice, use of vocabulary, organisation) was somewhat more challenging, with 52.3% in Year 1 and 45.1% in Year 3 reporting that this was very easy or easy. In their comments, teachers noted:

My teaching of English has become a lot more specific in relation to the teaching of skills, craft or process in writing (HYr14th)Footnote 2

Teaching 6th class, the biggest challenge with the writing is getting the children to use the “craft” element and have a flow of what they write (HYr36th).

Considerably fewer teachers found the implementation of writing assessment tools such as checklists or rubrics to be very easy or easy (32.8% in Year 1 and 42.6% in Year 3). In the main, teachers relied on conferencing with children to identify issues and also on reading and responding to their texts outside of school hours, which they reported to be time consuming, given the volume of writing that children produced. By Year 3, teachers recognised that there needed to be a greater focus on formative assessment. Many were becoming more comfortable with using it to inform teaching:

Successes: conferencing informing teaching the different aspects of writing workshop. (BYr34th)

Similar percentages of teachers (55.9% Year 1, 65.5%, Year 3) reported that scoring writing samples using a rubric was difficult or very difficult. It should be noted that, as a W2R rubric was in the process of being revised and further developed during initial implementation of W2R, some teachers constructed their own child-friendly rubrics and checklists to support peer and self-assessment. Additionally, the share session supported the development of a writing community and provided a forum for children to give constructive formative feedback to each other:

Each of the genres are explored in great detail and the children have the ability to assess their own work and work of their peers in an environment that allows free sharing of ideas (BYr35th).

Not all schools welcomed the emphasis on process writing in Pre-K and K. In one school, high levels of ‘cognitive dissonance’ (Thompson & Zeuli, 1999) were revealed with teachers arguing that W2R expectations for this age group were inappropriate: ‘Teaching junior infants (PreK-K) - I feel it is more realistic to go back to basics’ (GYr1Pre-K). It wasn’t until Year 3 that teachers there shifted both their thinking and practice:

I really love W2R, it has worked well in my class and I have put a lot of effort into it. We have really pushed junior infants this year and feel we are doing really well. (GYr3Pre-K)

Teachers’ confidence in implementing writing in W2R

A more direct measure of teacher confidence or self-efficacy was obtained in Year 3 when teachers were asked to indicate their level of confidence (very confident, confident, not so confident) in teaching different aspects of writing. The areas in which teachers were most confident (i.e., either ‘very confident’ or ‘confident’) were planning and teaching non-fiction writing genres (90.3%), planning and teaching fiction writing genres (85.3%), teaching spelling using a range of methods (82.3%), and supporting pupils in applying writing strategies (80.3%) (Table 2). Teachers’ high levels of confidence in teaching non-fiction and fiction writing genres may reflect the quality of materials provided as online resources by W2R and the advice provided by coaches on how to embed genre writing within a writing workshop model. It is noteworthy that teachers expressed less confidence in their ability to teach poetry (66.1%), and to select and use mentor texts for teaching writing mini-lessons (47.5%), activities that might have been expected to overlap with the teaching of different genres. Teachers’ confidence in teaching spelling using a range of methods (82.3%) may not relate directly to implementation of the writing process, where support for children’s development as spellers may be indirect (for example, via writing conferences or, where necessary, mini-lessons). Compared with other aspects of writing, teachers reported that they were less confident in planning and teaching mini-lessons related to the craft of writing (56.5% were either ‘very confident’ or ‘confident’), the processes of writing (64.5%) and skills of writing (69.3%). This is broadly consistent with the data in Table 1, where, for example, 45.2% of Year 3 teachers found teaching mini-lessons on the craft of writing to be ‘very easy’ or ‘easy’ (and, by inference, 54.8% found teaching such lessons to be difficult).

In a separate question not tabulated here, 54.1% of teachers in Year 3 reported that they were either very confident or confident in supporting pupils to engage in goal setting in literacy. As noted later, this could impact on implementation of the gradual release of responsibility model.

Impact of W2R on children’s writing

Teachers were generally positive about the impact of W2R on their children’s attitudes to writing, and they identified the aspects on which the children had improved since the beginning of the school year. In Year 1, at least one half of teachers noted a marked or a good improvement on multiple aspects of writing (Table 3), with the exception of spelling (39.1%) and grammar and punctuation (25.8%). In particular, teachers (71.9%) perceived that children’s knowledge of genre had improved as a result of more targeted genre teaching. One teacher noted that: The writing programme has resulted in an increase in motivation in creative writing and provides a consistent approach to the varying genres (BYr16th).

Teachers also noted that children had developed personal preferences for particular genres and in some cases, it was difficult to motivate them when doing a genre less appealing to them (HYr15th). Additionally, just over half of teachers (51.6%) felt that children’s level of vocabulary in writing had shown improvement.

Affective dimensions of writing which are critical to writing development (Graham, 2018; Berninger & Swanson, 1994) also showed strong improvement. Specific dimensions noted by a majority of teachers in Year 1 to have undergone a marked or good improvement included attitudes towards writing (80.3%), children’s confidence in writing (75.4%) and volume of writing (72.3%). This is reflected in teachers’ comments:

Children are gaining confidence and sense of pride in their folders (AYr16th)

It is enjoyable for the children who often ask “Can we do writing workshop now?” so that is encouraging for me. (BYr1Pre-K)

By Year 3, when many of the teachers would have been working with a different group of children than in Year 1 or were new to W2R, 48.3% reported a marked or good improvement in grammar and punctuation since the beginning of the school year, and 60.4% reported an improvement in spelling. Levels of perceived improvement for the remaining aspects of writing were similar to Year 1, with, for example, 81.3% of teachers reporting that children’s confidence in writing had improved, and 77.9% reporting that children’s attitudes towards writing had improved. In Year 3, the aspects of writing on which teachers perceived least improvement were grammar and punctuation (48.3%) and writing vocabulary (49.2%). The latter is not surprising given that teachers reported that they found the craft elements of writing more challenging to teach.

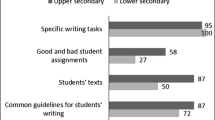

Impact of professional development

As noted above, teachers implementing the W2R framework had access to a range of supports to assist them with implementation. According to teachers in Year 1, the supports that were viewed as effective ‘to a great extent’ or ‘to some extent’ in developing their skills to implement the framework were: advice from the W2R coach (93.9%), advice from teaching colleagues (89.4%), sample teaching plans provided by W2R coaches (86.4%), and in-class demonstrations by coaches (80.4%) (Table 4). Other approaches viewed by about three quarters of teachers as useful included resources posted to an online repository (77.3%) and feedback on observations that was provided by coaches (74.6%). Responses to the open question confirmed the value teachers placed on the professional development:

I find it great and watching model lessons really showed how to go about teaching it, which was fantastic… the support from __was great - getting ideas/asking questions. (DYr1Pre-K)

It has made a great impact on my teaching through the professional readings, the teacher mentor and the online resources (EYr1K).

Fewer teachers in Year 1 (65.7%) noted access to professional readings including journal articles and chapters from research-to-practice books on writing was effective in supporting them. This is unsurprising, as, in the Irish context, teachers are generalists who teach all subjects and have little or no free time during the school day. Time for professional reading required time outside of the official school day, which was not ideal: Vast impact for the better. Extremely daunting at first. Requires a lot of time input, personal study and research to get to grips with theoretical and practical frameworks (HYr14th).

Research suggests professional learning should be seen as part of a “complex system rather than as an event” (Opfer & Pedder, 2011, p. 378) and that real change takes time. Though the coaches visited regularly in Year 1, as pre-W2R teaching was substantially different to the writing workshop model, teachers would have liked even more time with the facilitators, underscoring the individual nature of professional development, and teachers’ comfort levels with new ideas and practices: It is great to learn about new strategies and share resources. I would really like more in-school support with a facilitator. W2R has made me a better literacy teacher, I feel (FYr1PreK).

In Year 3, when support from associates was more limited than in Year 1, almost all teachers (93.5%) reported that teaching colleagues impacted on their skills to teach using the W2R framework ‘to a great extent’ or ‘to some extent’. This is an important finding, as it suggests that schools had evolved into professional learning communities and were better able to sustain the change process themselves. While they still very much welcomed the advice from W2R coaches (78.3%), it was notable that teachers were less reliant on presentations (56.9%), teaching plans provided by the W2R team (52.6%), resources posted in an online repository (51.7%) and professional readings (43.3%). Teachers commented that:

Structure is good, uniform throughout the whole school (FYr3Pre-K).

W2R has improved my work as a literacy teacher. The support given by the visiting teachers helped me to understand the new methods as well as implement them in the class (EYr35th).

Several teachers also reported that they had higher expectations for children as a result. For example:

Being part of W2R encourages me to have high expectations of my students no matter what their background. W2R stretches me professionally as a teacher (BYr33rd).

Finding from interviews with teachers

Findings from interviews with a random sample of teachers (n = 18) across the eight schools in Year 4 are presented according to six themes (time and autonomy, explicit teaching of mini-lessons across genres, writing assessment and feedback, engaged community of writers, attitudes towards professional development and perception of impact, and challenges for professional development) formed from the nine categories and 45 sub-categories derived from the coding process (Appendix, Table A1).

Time and autonomy

As noted above, prior to the W2R intervention, compositional writing was limited and largely traditional in approach. Given that time is a contentious issue in Irish schools (NCCA, 2010, 2023), teachers needed some convincing that daily time for writing was both needed and worth the investment. By Year 4, most interviewees (n = 16) reported they now allocated daily time to writing using a typical writing workshop structure; the other two indicated less frequent writing instruction (2–3 days weekly) with one remarking: I don’t have time to do it everyday, I do reading workshop Monday-Thursday, writing workshop Tuesday and Thursday and spelling Monday and Friday (G3rd).

Even when taught daily, time allocation varied due to a combination of factors including individual teachers’ time management, preferences, priorities and confidence to teach writing so frequently. As one experienced teacher noted: Now, I’ve probably worked more on the reading, and why is that? Because I just, we do it first and sometimes time constraints (A3rd). Though provision of opportunities for very young children to compose independently is critical to later literacy development (Ouellette & Sénéchal, 2017), for schools with junior classes (n = 6), this concept was very new. Most (n = 5) embraced it, noting it ensures that children develop a positive relationship with writing from the outset: Most importantly for me as an infant teacher, their willingness to write…I think, makes an impact on how they view it as they get into the older classes (BPre-K). This contrasts with the ‘back to basics approach’ advocated in another school in Year 1 of implementation (see above). Autonomy over writing topic has been identified as a key ingredient in successful writing workshops as it enhances student agency (Vaughn et al., 2020). Teachers associated it with the enhanced motivation they observed: Like I have no issues at all with motivation for writing, so really, I think the ownership plays a part (F1st). It was common for teachers to report that children were invested in their writing: They’re so proud of their work. I think it is because of a sense of achievement. They are writing really brilliant stuff. And they can see that themselves (H2nd).

Explicit teaching of mini-lessons across genres

Explicitly teaching mini-lessons was a new experience for all teachers and contrasted sharply with previous practice:

Now, you’re actually teaching writing. When I look back to myself, my teaching here, I mean I was probably guilty of you know, I taught sixth class for two years, going ‘here, write an essay’ but never actually telling them how to write a good one or how to make it better. (H2nd)

Importantly, all teachers reported that they prioritised craft mini-lessons, incorporating word choice, ideas, organisation and genre features. This was important in the context of our study as children at elementary level and in low-SES schools in particular need every opportunity to develop ‘word consciousness’ (Graves & Watts-Taffe, 2002) and an appreciation of the literary, aesthetic, and creative dimensions of writing (Kennedy & Shiel, 2019). Many teachers noted that children’s word choice had developed, highlighting that the vocabulary focus in the reading workshop was transferring into writing and classroom interaction:

The quality of their writing has definitely improved, but that’s probably because the quality of the teaching has improved. They’re getting a consistent message right from Pre-K to 6th ….even their word consciousness and their vocabulary, the words they choose, that’s actually a thing that has really come on. (E3rd.)

There is debate in the literature on the importance of explicit instruction in writing. On the one hand, some researchers (Koster et al., 2015) have highlighted the importance of metacognition if writers are to value and internalise modelled strategies and use them flexibly when composing. On the other hand, de Smedt et al. (2019) have hypothesised that explicit instruction may unintentionally constrain students’ writing and result in more ‘controlled motivation’, highlighting the fine line between instruction to lift the quality of writing and prescription of writing qualities. Though coaches had modelled the gradual release of responsibility model (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983) and advocated the use of high-quality mentor texts, there was variation in quality of implementation. While teachers reported modelling, they did not specifically mention metacognitive dimensions and the source of exemplar texts was not always clear:

I would start off with a lot of examples of that genre and I think that’s quite important. I found that’s kind of what helped them produce better writing samples. So even just getting them colour coding the different features, underlining topic-specific vocabulary or an interesting word…that really helped them. Then make an anchor chart…that would almost become a checklist for them. (B6th)

Coaches shared lists of mentor texts and websites to build teacher knowledge of current children’s literature as teachers reported that sourcing quality literature for mini-lessons was a challenge. Teachers highlighted that children took more notice of craft lessons when high-quality mentor texts across genres were utilised:

We got a lot of nonfiction books last year, which were brilliant for the report-writing. exciting nonfiction books, the ---- and ----, all those ones. And the difference in the reports that they wrote from January to May was staggering. Just by taking a different approach to it. (G4th)

Schools were encouraged to build a framework that ensured children had opportunities to write in each genre each year. In-depth genre study was a new venture which teachers appreciated:

We’re really looking at different genres in a way that we’ve nodded to before, whereas now we’re going into them in a lot more depth. Things like poetry writing, procedure writing, you might have flitted with them before but not given them the same time that they’re now getting. (C5th/6th)

The majority indicated they had taught a wide range of genres, integrating writing within cross-curricular units to build further reading and writing connections. This contrasts with research highlighting that children are not often provided with opportunities to write in a range of genres (e.g., Parr & Jesson, 2016).

Though small group skills lessons based on formative assessment were advocated by coaches, there was variation in the frequency of these lessons, with some teachers regularly scheduling such lessons and others not highlighting them at all during interview:

There’d be other days where you’d only work with a certain group for the mini-lesson, if half the class have no problems with their full stops/capital letters, those kind of mini-lessons, another group might need more help with them. (G4th)

Supporting children to develop awareness of the strengths and weaknesses in their writing (Graham et al., 2015; Kennedy & Shiel, 2022) requires regular use of formative assessment tools.

Writing assessment and feedback

All teacher reported providing feedback to children in a variety of ways. Most often cited was the value of conferencing which had particularly benefited younger children:

I’ve organized so he’s (learning support teacher) in class at that time. So we’re both there to conference because they’re young. At the start we weren’t doing that… they came on loads when all got a chance to conference a lot (H2nd).

Some teachers highlighted sharing success criteria and developing checklists with children to support peer conferencing and self-assessment:

Checklists. I find that’s the easiest way for them to do it and they can see really clearly, or I might get them to do a peer assessment, so has your partner got everything? Then they’d tick yes or no (H5th).

In the absence of observational data, it is unclear to what degree the decontextualised academic language register was specifically targeted and taught systematically. However, a few teachers made particular reference to the language register that children had acquired:

The children have a really, really top understanding, in my opinion, of the different genres, a lot more so than other children I would have had, that I’ve taught in a different setting They’ve a great theoretical understanding of what they’re doing. That’s the difference. (H5th)

In general, teachers communicated high expectations and gave specific feedback to children and as the year progressed and mini-lessons accumulated, they ‘upped the ante’ (Pressley et al., 2001), holding children accountable for transferring ideas taught in mini-lessons into their writing.

Only about a third of interviewees reported using rubrics to track development and this correlates with the high percentage of teachers (43.5%) in Year 3 who indicated in questionnaires that they were not confident in using rubrics. Though most of the teachers were aware of the W2R Assessment Rubric (see Kennedy & Shiel, 2022) it was not generally used for tracking purposes in the current study as it was still in development. Some teachers reported using it for planning and considering expectations for the quality of writing:

The W2R rubrics they’re great I find for using them to plan. You’re looking and kind of saying, okay, here’s where they are, here’s where I want them to go, so this is what I’m going to teach (H2nd).

A further avenue for peer feedback was provided within the share session occurring at the end of each workshop, reinforcing the social dimension to writing.

Factors contributing to development of an engaged community of writers

Consistent with questionnaire data, most teachers reported that children’s attitudes towards writing were now more positive. In line with research on engagement and agency (Vaughn et al., 2020; Camacho et al., 2021), they cited the daily time allocated to writing as a key factor which supported children in viewing themselves as writers, while autonomy and choice had given a purpose to writing. Teachers new to W2R and the concept of a writing workshop reported that they had not seen such levels of writing engagement before:

Compared to where I taught before, it wasn’t a DEIS school, it was a very affluent area, and there was not the same love of writing or reading. There just wasn’t (G4th).

As genres were repeated more than once throughout the year, toward the end of the year, teachers allowed children complete choice. Teachers noted that genre choice was a key factor in engagement as children naturally favoured some genres over others: When you tell them that they have choice they cheer! The love to choose their genre…when they find their niche and interest in writing they write pages! (G4th).

Teachers of early grade levels in particular (PreK, K, 1st) commented on children’s willingness to have a go at writing, which they attributed to balancing attention to authorial and secretarial dimensions of writing – aspects that have been highlighted as essential in approaches to early writing (Kennedy & Shiel, 2022; Scull et al., 2020). Teachers nurtured children to be ‘brave spellers’ (Schrodt et al., 2020) who concentrated on content and voice when writing independently:

‘Give it your best guess. Make your sounds. What do you think comes next? What little words can you find hidden in that, that might help to you?’ To be brave enough to do that, it can be challenging for the children to say, ‘Everything doesn’t have to be right’ (CK).

Teachers reported that provision of a supportive peer audience was pivotal to engagement and confidence. It promoted writing as a social act and created a sense of writing community (Graham, 2018) as children learned to listen and provide feedback: Hearing other people in the class reading (their writing) inspires them a little bit. So that works well, the feedback (B1st). It also enhanced children’s self-esteem and confidence to share writing with an audience beyond the classroom:

It’s incredible. Their confidence, their self-esteem in writing. They see themselves as writers. They see themselves as readers…the share sessions at the end, they will get up and share in front of assemblies (E3rd).

Teachers also commented on the improved quality of writing that children produced which they ascribed to several factors, including the daily time afforded to writing, the differentiation and small group work which had made the writing experience positive and manageable, the conferencing and feedback which supported their identity development, and the quality of teaching. Professional development was key to supporting teachers in creating responsive, democratic and engaging classrooms.

Attitudes towards professional development and perception of impact

Mirroring questionnaire data, teachers were largely positive about the multifaceted nature of PD offered which they credited with changing their thinking as well as their practice and heightened expectations for children’s development. Comments such as these were common:

but it’s definitely changed my way of teaching, how I approach teaching writing. that’s been huge for me…. when I was teaching infants (PreK) before W2R, part of it could have been that I probably didn’t think that they could go that far, you know? But once you see that it’s possible, you’re really able to bring them on (BPreK).

Teachers particularly valued coaches’ expertise and advice highlighting that: having ‘access to somebody who has more learning in that area, more experience…, whom you can sound things off’ (C5th/6th) was vital. They also highly valued coach demonstrations in classrooms: She did a little bit of modelling, talking around things, and that was terrific. To see it in action and to see the children react to it (C5th /6th). These occasions provided the kinds of ‘vicarious experiences’ (Bandura, 1997) which were pivotal to supporting teacher self-efficacy and in helping them to envision themselves as doers of the innovation. A third feature of the PD which was valued was the provision of resources, exemplars and structures which were particularly welcomed by less experienced teachers:

I think when you’re a young teacher as well. I felt clueless, so it was nice to have kind of a routine to become accustomed to…It gives a real focus to my planning as well as to their learning…the hour and a half…. I never feel at sea, it was really manageable. (D2nd/3rd)

Teachers’ prior experiences with writing also fed into their belief system about writing (Graham, 2018). Though Cremin and Oliver (2017) highlighted that teachers’ attitudes towards writing may be mediated by low self-confidence and negative writing histories, responsive PD can build confidence and change perspectives:

I remember. I hated creative writing because it was sort of like, ‘here, write’...I was a bright intelligent kid, why didn’t I like it? It was because it was like here’s just a blank paper… We break it down, we show them actually how…… I tend to find I could do it all day. You want to give the time to it because it’s going so well. (H2nd)

Many teachers reported they now enjoyed teaching writing more and that the approaches used had engendered a love of literacy amongst children:

Funny enough, I enjoy teaching it more now. (H5th)

I just think it’s ignited a love for teaching literacy more so… that I’m just a facilitator at times, that they can learn a lot from each other. They really do enjoy choice and when they have the freedom to write about what they want and read what they want…(B6th).

In most schools, the whole school approach to PD was successful in building a sense of collegiality, a strong culture of teacher collaboration and a vision for writing. This was evidenced in the level of collaboration reported and sharing of resources:

It’s so embedded in the school you see…a bank of resources and things have been built up… We introduced a folder in each classroom, so if you’re someone who found something that’s great for narratives, you keep a copy, you know so you could show other people. (H2nd)

Additionally, demonstrating confidence in their PCK, teachers initiated peer coaching and observation to support teachers new to their school and to induct them into the practices of a writing workshop which was valued: I got to observe it being carried out in some of the classrooms, and the staff are really supportive (B6th).

Challenges for professional development

For teachers new to W2R, it was ‘a steep learning curve’ (H5th) and a very different way of teaching. Translating PD ideas into motivating and engaging lessons tailored to children’s interests and stages of development was particularly challenging for young teachers when they were new to a class level and still trying to hone their general teaching and classroom management skills. It was further compounded by their level of confidence to teach writing:

To be honest, writing is one I’m not really confident on as a teacher… Now I find it very different from the juniors because I have 6th class now and they’re not as eager to please or they’re not as interested. Like they are difficult to get focused. That’s what I find tough (A6th).

Even for experienced teachers, who had benefitted from the professional development provided each year, changing grade level or returning to mainstream classroom teaching presented challenges:

Really, it’s like starting afresh with a new grouping… ‘I know how to do this with 2nd or 3rd and 4th, but it’s a new kind of programme to do it with a different age grouping’. (CK)

This year, I really felt like, ‘oh, my gosh, what do I do, again? I’ve forgotten a lot of it’. (B1st: returning to mainstream)

Such findings underscore the complexity and situated nature of professional development. As Opfer and Pedder (2011, p. 378) highlight, teacher learning should be seen as a ‘complex system rather than as an event’ and consideration must be given to teachers’ motivation, emotions, and self-efficacy, particularly when substantive change is anticipated. One teacher noted that: Some people will love it and take to it and do over and above and then others will come slower to it. (H2nd).

Discussion

We conclude this paper by discussing key findings related to each of the research questions and consider their implications for policy and practice. We begin by highlighting study limitations.

Limitations

First, it was not possible to implement an experimental study to assess the initial implementation of the writing component of W2R. Hence, there was no external comparison group in the current study. Second, we drew on teacher self-report data (responses to questionnaire items and semi-structured interviews) for contextual information. Though it was not possible to gather in the current study, observational data would have further enhanced findings. A third limitation was that the reading aspects of W2R were being introduced alongside the writing dimensions over the four years, which may have increased the challenge for teachers as they grappled with multiple components. The limitations should be borne in mind in interpreting the outcomes.

Key findings and implications

RQ1. What conditions, resources and kinds of professional development supported teachers in low-income schools in changing their current classroom practice for writing to a research-informed writing workshop approach?

Teachers appreciated the multifaceted nature of the professional development and reported that it was pivotal in supporting them to structure their instructional time for writing, to plan a variety of mini-lessons and to incorporate evidenced-based practices into writing instruction.

In Year 1, teachers particularly valued the regular visits, advice and support of the W2R coach, the variety of resources provided, the lessons modelled by coaches, the relationships that were built, and the feedback from coaches on their teaching. These practices provided the vicarious, social persuasion and mastery experiences (Bandura, 1997) that built teacher ‘content and pedagogical content knowledge’ for writing (Shulman, 1987) and their confidence and sense of self-efficacy to experiment with new approaches.

The interaction between coaches and teachers set the tone for collaboration. It opened up dialogue amongst teachers within and across class levels. Teachers highlighted that they were now more likely to discuss issues and seek support and advice from colleagues, particularly as they began to assume greater responsibility for sustaining changes to practice in Years 3–4. Several schools established strong cultures of collaboration within and across class levels, creating a shared vision and climate conducive to sustaining new practices. As teachers’ self-efficacy grew, many opened up their classrooms to peers new to their school to observe them teaching writing.

Though teachers found the change process daunting initially, given the scale of change involved, the whole school approach to PD contributed to the development of a schoolwide vision for writing and successfully embedded the writing workshop model. However, challenges to continuity identified included the churn that occurred within schools as teachers took on new roles (e.g., moving from learning support back to mainstream teaching), moved class level (as occurs regularly in the Irish context) or transferred to other schools. Teachers were of the opinion that they would need further PD support in these new contexts. This finding underscores the situated nature of teaching and the level of support teachers require to successfully adapt ‘content and pedagogical content knowledge’ (Shulman, 1987) to children’s needs and stages of development.

In line with previous research (e.g., Opfer & Pedder, 2011), our findings also indicate that the affective dimensions of PD are also key mediators of teacher engagement with professional learning. Teachers in the study came to professional learning with a variety of experiences, beliefs, attitudes and identities and were on a continuum of change, mediated by their own values and philosophies of teaching. The customised nature of the PD and access to coaches with experience of teaching in the realities and complexities of low-income schools was highlighted by teachers as critical in supporting them in shifting not only their practice but their thinking and beliefs. Furthermore, children’s enhanced motivation and engagement – which occurred early in the change process – cemented their commitment to change.

Together, these factors highlight the complexity involved in successfully scaling PD within and across schools serving large numbers of low-SES children when widespread changes to practice are required. Our findings suggest that a one-size-fits-all approach may not result in the desired outcomes and that real change takes time. In designing PD, policy makers and professional developers should attend to the collective and individual needs of participants and the process of change and should provide support to each context that is customised to maximise teacher and school capacity to sustain new practices into the future. It is also critical to build early success into the process.

RQ2. How did teachers view the implementation of the writing component of the W2R framework and how did their views evolve over time?

As noted earlier, the writing workshop model differed substantially from teachers’ previous practice for teaching writing. Previously, writing was taught once or twice a week, in contrast to the hour a day recommended in research (Graham et al., 2012). For all, moving from an hour of writing time weekly to a daily allocation of 40–45 min was a significant change, along with mini-lessons taught in the context of children’s writing rather than through workbooks, and provision of greater choice and autonomy for children. By Year 4, teachers had largely succeeded in providing daily time to write, in line with the guidance provided by coaches. This was an important development as without time to write it is unlikely that children’s writing will develop to the level needed for success in school and adult life (Graham et al., 2012).

It took time for teachers to become comfortable with all elements of a writing workshop, and for some teachers, high levels of ‘cognitive dissonance’ (Thompson & Zeuli, 1999) slowed progress as they grappled with new ways of teaching and assessing. A further factor to consider is that W2R is a tier one (Swanson et al., 2017) multi-component intervention which was also targeting aspects of reading and word study. While these were introduced on a phased basis and a spiralling approach was used to revisit aspects of writing, it was challenging for teachers to continue to learn and layer new aspects of literacy into their teaching to ultimately build to a research-informed 90-minute framework. This may have created implementation overload for some. It highlights the challenges involved in school change and the need for more intensive sustained professional development over extended periods of time to consolidate and embed new practices.

On balance, it can be concluded that the majority of teachers were successful in implementing the writing component of W2R. There was evidence that teachers were now incorporating mini-lessons into their writing workshop, though there was variation in how the lessons were taught. By Year 3, while the majority of teachers across the 8 schools reported that teaching the secretarial aspects of writing (including spelling) was easy or very easy, just under half found the craft lessons easy, indicating that further professional development was warranted. These are more challenging aspects of writing development, and in a marginalised school context, where oral language, including vocabulary development tends to lag behind that of non-marginalised students (Nelis & Gilleece, 2023), these dimensions require sustained explicit attention. Although all the interviewees reported teaching elements of craft, it was not clear to what extent the lessons drew on all steps of the gradual release of responsibility model or the level and quality of the mentor texts selected, each of which would impact on the effectiveness of teaching and on the quality of writing. Further, just 54.1% of teachers were confident or very confident in supporting students to engage in goal setting in Year 3. As Troia et al. (2009) noted, attention to reflection on and specificity of goal setting is important in developing children’s metacognitive awareness and in improving writing.

It is noteworthy that, while 82.3% of teachers in Year 3 reported that they were very confident or confident in teaching spelling using a range of methods, just 60.5% reported a marked or good improvement in spelling. It may be that, while a range of methods are used to teach spelling, students struggle to transfer that knowledge to the writing context and require further support in doing so (for example, through targeted small group mini-lessons). On the other hand, over 80% of teachers in Year 3 were very confident or confident in their ability to teach fiction and non-fiction genres, and 75.9% of teachers reported a marked or good improvement in children’s knowledge of writing genres in Year 3. This is encouraging and is supported by interview data confirming that children used a wide range of genres throughout the school year, with the writing workshop providing a structure that allowed teachers to move from one genre to another without loss of quality.

Research highlights the importance of timely feedback to students which can be in the form of teacher conferencing or peer and self-assessment (Graham et al., 2015). Three-fifths of teachers reported that conferencing was easy or very easy while slightly fewer found it easy to use the data to plan responsive lessons. About a third of teachers were using rubrics to support assessment and interview data indicated that many teachers were using peer and self-assessment. All teachers also facilitated share sessions which provided opportunities for children to build a sense of self-efficacy and to develop the language of response which teachers noted had shown improvement.

Overall, much was achieved and provided a firm basis for further development, particularly in relation to greater specificity in teaching and using assessment data to inform teaching. Teachers showed evidence of implementing research-informed practices in line with the research outlined in the literature review.

Notes

In the case of questionnaire comments, codes include School (A to H), Year in which questionnaire was completed (Year 1 or Year 3), and grade level (Pre-K to 6th) (e.g., HYr14th indicates that a Grade 4 teacher in School H provided the comment in Year 1). For interview data, codes include School and grade level only (e.g., H2nd – School H, Grade 2 teacher).

References

American Institutes for Research. (AIR) (2021). Teachers College reading and writing project study. Author https//d17j94wz7065tl.cloudfront.net/calkins/AIR-UOS-Study-Technical-Brief-2021.pdf.

Au, K. H. (2005). Negotiating the slippery slope: School change and literacy achievement. Journal of Literacy Research, 37, 267–288. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3703_1.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Berninger, V. W., & Swanson, H. L. (1994). Modifying Hayes and Flower’s model of skilled writing. In E. Butterfield (Ed.), Children’s writing; Toward a process theory of development of skilled writing (pp. 57–81). JAI Press.

Bruning, R. H., & Kauffman, D. F. (2016). Self-efficacy beliefs and motivation in writing development. In C. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (2nd ed., pp. 160–173). Guilford Press.

Calkins, L. M. (1986). The art of teaching writing. Heinemann.

Camacho, A., Alves, R. A., & Boscolo, P. (2021). Writing motivation in school: A systematic review of empirical research in the early twenty-first century. Educational Psychology Review, 33, 213–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09530-4.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Inquiry as stance. Practitioner research for a new generation. Teachers College Press.

Cordingley, P., Higgins, S., Greany, T., Buckler, N., Coles-Jordan, D., Crisp, B., Saunders, L., & Coe, R. (2015). Developing great teaching: Lessons from the international reviews into effective professional development. Teacher Development Trust. https://tdtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/DGT-Full-report.pdf.

Cremin, T., & Oliver, L. (2017). Research Papers in Education, 32(3), 269–295, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1187664.

De Smedt, F., Merchie, E., Barendse, M., Rosseel, Y., De Naeghel, J., & Keer, H. (2017). Cognitive and motivational challenges in writing: Studying the relation with writing performance across students’ gender and achievement level. Reading Research Quarterly, 53, https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.193.

De Smedt, F., Graham, S., & Van Keer, H. (2019). The bright and dark side of writing motivation: Effects of explicit instruction and peer assistance. The Journal of Educational Research, 112(2), 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2018.1461598.

Delaney, E., McAteer, S., Delaney, M., McHugh, G., & O’Neill, B. (2023). PIRLS 2021: Reading results for Ireland. Educational Research Centre.

Department of Education and Science (DES). (2005). DEIS: Delivering equality of opportunity in schools) An action plan for educational inclusion. Author.

Department of Education and Skills (2017). DEIS plan 2017: Delivering equality of opportunity in schools. Author. Retrieved from: http://www.gov.ie/en/publication/0fea7-deis-plan-2017/

Desimone, L., & Garet, M. S. (2015). Best practices in teachers’ professional development in the United States. Psychology. Society & Education, 7(3), 252–263. https://doi.org/10.25115/psye.v7i3.515.

Dockrell, J. E., Marshall, C., & Wyse, D. (2015). Evaluation of talk for writinghttps://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/uploads/pdf/Talk_for_Writing.pdf.

Gadd, M., & Parr, J. (2017). Practices of effective writing teachers. Reading and Writing, 30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-017-9737-1

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Publishing.

Graham, S. (2018). A revised writer(s)-within-community model of writing. Educational Psychologist, 53(4), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2018.1481406.

Graham, S. (2020). The sciences of reading and writing must become more fully integrated. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1), S35–S44. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.332.

Graham, S., Bollinger, A., Booth Olson, C., D’Aoust, C., MacArthur, C., McCutchen, D., & Olinghouse, N. (2012). Teaching elementary school students to be effective writers: A practice guide (NCEE 2012–4058). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/publications_reviews.aspx#pubsearch.

Graham, S., Hebert, M., & Harris, K. R. (2015). Formative assessment and writing: A meta-analysis. The Elementary School Journal, 115(4), 523–547. https://doi.org/10.1086/681947.

Graham, S., Liu, X., Bartlett, B., Ng, C., Harris, K. R., Aitken, A., Barkel, A., Kavanaugh, C., & Talukdar, J. (2018). Reading for writing: A meta-analysis of the impact of reading interventions on writing. Review of Educational Research, 88(2), 243–284. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317746927.

Graham, S., Kiuhara, S. A., & MacKay, M. (2020). The effects of writing on learning in science, social studies, and mathematics: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 90(2), 179–226. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320914744.

Graves, D. (1983). Writing: Teachers and children at work. Heinemann.

Graves, M., & Watts-Taffe, S. M. (2002). The place of word consciousness in a research-based vocabulary programme. In A. E. Farstrup, & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), What the research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp. 140–165). International Reading Association.

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (1980). Identifying the organisation of writing processes. In L. Gregg, & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive processes in writing (pp. 3–30). Erlbaum.

Kennedy, E. (2014). Raising literacy achievement in high-poverty schools: An evidence-based approach. Routledge.

Kennedy, E. (2018). Engaging children as readers and writers in high-poverty contexts. Journal of Research in Reading, 41(4), 716–731. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12261.

Kennedy, E., & Shiel, G. (2010). Raising literacy levels with collaborative on-site professional development in an urban disadvantaged school. The Reading Teacher, 63(5), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.63.5.3.

Kennedy, E., & Shiel, G. (2019). Writing pedagogy in the senior primary classes: Knowledge skills and processes. National Council of Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). https://ncca.ie/media/4121/writing-pedagogy-in-the-senior-primary-classes.pdf.

Kennedy, E., & Shiel, G. (2022). Writing assessment for communities of writers: Validation of a scale to support teaching and assessment of writing in Pre-K to Grade 2. Assessment in Education: Principles Policy and Practice, 29(2), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2022.2047608.

King, F., French, G., & Halligan, C. (2022). Professional learning and/or development (PL): Principles and practices. A Review of the Literature Department of Education (Ireland). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7250425.

Koster, M., Tribushinina, E., de Jong, P. F., & van den Bergh, H. (2015). Teaching children to write: A meta-analysis of writing intervention research. Journal of Writing Research, 7(2), 249–274. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2015.07.02.2.

Liou, Y., & Canrinus, E. T. (2020). A capital framework for professional learning and practice. International Journal of Educational Research, 100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101527.

Lipson, M. Y., Mosenthal, J. H., Mekkelson, J., & Russ, B. (2004). Building knowledge and fashioning success one school at a time. The Reading Teacher, 57(6), 534–545. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.57.6.3.

Madden, N. A., Slavin, R. E., Logan, M., & Cheung, A. (2011). Effects of cooperative writing with embedded multimedia: A randomized experiment. Effective Education, 3(1), 1–9.

Myhill, D. A., Jones, S. M., Lines, H., & Watson, A. (2012). Re-thinking grammar: The impact of embedded grammar teaching on students’ writing and students’ metalinguistic understanding. Research Papers in Education, 27(2), 139–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2011.637640.

Myhill, D., Cremin, T., & Oliver, L. (2023). Writing as a craft: Re-considering teacher subject content knowledge for teaching writing. Research Papers in Education, 38(3), 403–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2021.1977376.

National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) (2010). Curriculum overload in primary schools: An overview of national and international experiences Author.

National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) (2023). The primary curriculum framework: For primary and special schools. Author. https://curriculumonline.ie/getmedia/84747851-0581-431b-b4d7-dc6ee850883e/2023-Primary-Framework-ENG-screen.pdf.

National Council of Teachers of English. (NCTE). (2016). Professional knowledge of the teaching of writing. National Council of Teachers of English. http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/writingbeliefs.

Nelis, S. M., & Gilleece, L. (2023). Ireland’s National assessments of Mathematics and English Reading 2021: A focus on achievement in urban DEIS schools. Educational Research Centre.

Opfer, V. D., & Pedder, D. (2011). Conceptualizing teacher professional learning. Review of Educational Research, 81(3), 376–407. https://doi-org.dcu.idm.oclc.org/10.3102%2F0034654311413609.

Ouellette, G., & Sénéchal, M. (2017). Invented spelling in kindergarten as a predictor of reading and spelling in Grade 1: A new pathway to literacy, or just the same road, less known. Developmental Psychology, 53(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000179.

Paris, S. G. (2005). Reinterpreting the development of reading skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 40(2), 184–202. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.40.2.3.

Parr, J., & Jesson, R. (2016). Mapping the landscape of writing instruction in New Zealand. Reading & Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 29, 981–1011. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s

Pearson, D. P., & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 317–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476X(83)90019-X.

Pressley, M., Allington, R. L., Wharton-McDonald, R., Block, C., C., & Morrow, M., L (2001). Learning to read: Lessons from exemplary first-grade classrooms. Guildford.

Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2007). Influencing children’s self-efficacy and self-regulation of reading and writing through modeling. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 23, 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560600837578.

Scull, J., Mackenzie, N. M., & Bowles, T. (2020). Assessing early writing: A six-factor model to inform assessment and teaching. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 19(2), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-020-09257-7. Scopus.

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411.

Slavin, R. E., Lake, C., Inns, A., Baye, A., Dachet, D., & Haslam, J. (2019). A quantitative synthesis of research on writing approaches in grades 2 to 12 Best Evidence Encyclopaedia (BEE) Center for Research and Reform in Education, Johns Hopkins University. https://d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/production/documents/guidance/Writing_Approaches_in_Years_3_to_13_Evidence_Review.pdf?v=1702283952.

Swanson, E., Stevens, E., Scammacca, N., Capin, P., Stewart, A., & Austin, C. (2017). The impact of tier 1 reading instruction on reading outcomes for students in grades 4–12: A meta-analysis. Reading and Writing, 30(8), 1639–1665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-017-9743-3.

Thompson, C., & Zeuli, J. S. (1999). The frame and the tapestry: Standards-based reform and professional development. In L. Darling-Hammond, & G. Sykes (Eds.), Teaching as the learning profession: Handbook of policy and practice (pp. 341–375). Jossey-Bass.

Troia, G. A., Lin, S. C., Monroe, B. W., & Cohen, S. (2009). The effects of writing workshop instruction on the performance and motivation of good and poor writers. In G. A. Troia (Ed.), Instruction and assessment for struggling writers: Evidence-based practices (pp. 77–104). Guilford Press.

Vaughn, M., Jang, B. G., Sotirovska, V., & Cooper-Novack, G. (2020). Student agency in literacy: A systematic review of the literature. Reading Psychology, 41(7), 712–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2020.1783142.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation, pp. 13–39, Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50031-7.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions