Abstract

Online peer feedback has become prevalent in university writing classes due to the widespread use of peer learning technology. This paper reports an exploratory study of Chinese-speaking undergraduate students’ experiences of receiving and reflecting on online peer feedback for text revision in an English as a second language (L2) writing classroom at a northeastern-Chinese university. Twelve students were recruited from an in-person writing class taught in English by a Chinese-speaking instructor and asked to write and revise their English persuasive essays. The students sought online peer feedback asynchronously using an instant messaging platform (QQ), completed the revision worksheet that involved coding and reflecting on the peer feedback received, and wrote second drafts. Data included students’ first and second drafts, online peer feedback, analytic writing rubrics, revision worksheets, and semi-structured interviews. The quantitative analysis of students writing performance indicated that peer feedback led to students’ revisions produced meaningful improvements in the scores between drafts. The results of qualitative analyses suggested that: (1) the primary focus of peer feedback was content; (2) students generally followed peer feedback, but ignored disagreements with their peers; (3) students strategically asked for clarification from peers on the QQ platform when feedback was unclear or confusing while collecting information from the internet, e-dictionaries, and Grammarly; and (4) students thought they benefited from experiencing the peer-mediated revision process. Based on the results, we provide recommendations and instructional guidance for university writing instructors for scaffolding L2 students’ text revision practices through receiving and reflecting on online peer feedback.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Several studies have documented that students could develop their English writing skills by actively using socio-cognitive learning sources during the writing and revision process (e.g., Duijnhouwer et al., 2010; Graham & Alves, 2021; Zumbrunn et al., 2016). An example of a socio-cognitive learning source is feedback from peer students, which can activate students’ self-reflective thinking for self-assessment while enhancing English writing performance (Graham & Perin, 2007; Graham et al., 2015; Li, 2023; Min & Chiu, 2021; Papi et al., 2020). Peer feedback is particularly informative in persuasive writing, a genre that requires a fine balance of rhetorical strategy, evidence presentation, and clear language usage to convince the readers of the writer’s opinion (Harris et al., 2019; Li, 2022a). While native English-speaking students are the leading focus group in most studies, few studies have explored text revision processes of English persuasive writing via peer feedback among L2 students, a sizable group still struggling with English persuasive writing and revision practices (Li & Zhang, 2021; Zhang et al., 2023). Further, given the omnipresence of modern technology in writing teaching and learning, peer feedback is increasingly likely to occur online (Chang, 2015; Guardado & Shi, 2007; Li, 2022a). Thus, investigating L2 students’ experiences of receiving and reflecting on online peer feedback, including how it shapes their text revision behavior in English persuasive writing, appears timely.

Enhancing students’ text revision through peer feedback

Studies examining peer feedback in various writing learning contexts, have reported that it contributes to the development of students’ writing learning skills. One notable exploratory intervention study conducted by Lundstrom and Baker (2009) examined the effectiveness of peer feedback for improving text revision among 91 L2 English students in the United States. Findings revealed that the students’ writing skills before-and-after peer feedback incurred specific gains (i.e., improved writing scores). Similarly, Berggren (2015), who investigated whether and how Swedish secondary students could improve their revision behavior through peer-to-peer interactions in English writing, found that peer feedback raised students’ audience awareness and motivated them to revise higher-order writing issues (e.g., contents, organization, and logic). Supporting the learning-by-reviewing hypothesis, Cho and MacArthur (2010) reported that US undergraduates who gave peer feedback could develop their skills of English academic writing and revision across the disciplines more than those who received the feedback. Further, Cho and Cho (2011) also found that peer reviewers were more able to enhance their L1 academic writing performance when they gave feedback. Specifically, giving microscopic criticism and macroscopic praise significantly benefited them.

Nevertheless, some studies (e.g., Li et al., 2010; Nicol, 2010) have reported contradictory results that receiving peer feedback could contribute to the reviewer’s revision skills improvement more than providing feedback. Moreover, Trautmann (2006) examined whether native English-speaking students could improve text revision skills by giving or receiving peer feedback. The finding implied that a critical factor in inducing students to revise was the feedback they received, and 70% of students in their study believed their writing skills are developed because of receiving peers’ suggestions. A more recent study conducted by Min and Chiu (2021) also found that L2 English students in Taiwan made significantly more macrostructure meaning changes based on the peer feedback they received than on those they gave for the writing draft during the online peer review.

In sum, the inconclusive results on the relative effects of giving versus receiving peer feedback on students’ text revision improvement suggest that more empirical studies should be conducted because peer review is not a simple one-round activity (Papi et al., 2020; Yu & Lee, 2016). From the peer feedback receiver side, especially for students with high-level self-regulated learning skills, students are more likely to seek further help from their peers by clarifying and negotiating their thoughts, or by accessing other sources in their social learning contexts such as the internet, dictionary, and grammar book for further advice.

Students’ self-reflection on peer feedback for text revision

Although the studies reviewed above have demonstrated that peer review contributes to students’ writing skills development, there has been limited research on how students revise based on self-reflection or peer feedback. As Zimmerman and Kitsantas (2002) articulated, students could gain revision skills by reflecting and judging peers’ responses to revise their own written text. However, many students do not really draw on self-reflections on their writing and revision learning processes on a timely basis (van Velzen, 2002). Additional instructional interventions that motivate students to self-reflect on the peer comments, therefore, may be necessary. Flower (1994) argued that students must verbalize their own cognitive thinking processes, and that such conscious verbalization is a form of reflective practice and critical thinking. Alitto et al. (2016) found that when allowing US elementary school students to write their reflective goal and subgoals for revision based on peer-mediated feedback, they outperformed a comparison group on production-dependent writing indices (i.e., the number of words spelled correctly, total number of words written, number of correct word sequences. The decision-making in writing and revision of university-level writing learners has been reported to be based upon the recurrent mental action of their own goals and plan. In an exploratory study of online peer reviews for US undergraduate students in an English for academic (psychology) program, Zhang et al. (2017) investigated peer feedback as a socio-cognitive source that triggered text revision. Results indicated that students enhanced their writing skills and created significant revisions across high-level (content) and low-level (language) issues. An online retrospective tool called “Lessons Learned” was applied in the study to ask students to draw self-reflections for their future writing and revisions. The researchers suggested that self-reflection should be guided with clear guiding questions about how students can act on their writing on their revision plan before writing the second draft. As integral components in strategy instruction and feedback, self-reflection and revision planning need to be highlighted.

Studies on students’ use of peer feedback in the text revision process have mainly focused on L1 students, with only a few on second-language writing. Among these studies, Duijnhouwer et al. (2010) found that graduate-level L2 English students in the Netherlands who reflected on their progress via feedback (by completing a reflection journal) could better identify their writing problems and revise them. Similarly, Yang (2010) observed that Taiwanese university students who reflected on revisions could enhance their L2 English writing during online peer interactions. In other words, by participating in self-evaluation and the self-monitoring of peers’ comments, students could adjust their writing learning strategies and gradually become self-regulating writers.

These findings suggest that students’ reflections can be unveiled by using a revision plan worksheet to document the text revision process when reflecting on peer feedback. Within the worksheet, other qualitative data and analyzing approaches can also be applied, such as drafting self-reflection prompts and developing follow-up interview guidelines to further explore the nature of this peer-mediated revision process.

Online learning environments, peer feedback, and students’ text revision

Incorporating online interactive platforms to facilitate writing instruction and feedback has become popular in recent decades (Li, 2023; Li & Zhang, 2021; Yu & Hu, 2017). With the development of interactive platforms such as WeChat, QQ, and blogs, online peer interaction has emerged as a way to promote the text revision process (Cho & MacArthur, 2010; Zhang et al., 2017). Studies have highlighted two distinct characteristics of online peer review: time (immediacy), and space (limitless, or beyond geographic borders), both of which have the potential to impact students’ learning outcomes (Li, 2022a; Xu & Yu, 2018; Zhang et al., 2020). In this respect, as Lu (2016) summarized, the benefits of online peer feedback lie in the timeliness of its assessment, negotiation of meaning, and discussion of higher-order writing issues (e.g., contents, organization, and logic), which is quite different from instructors’ written corrective feedback. Furthermore, conducting online peer review provides a comfortable learning environment for students with the possibility to become more self-directed and self-regulated (Zumbrunn et al., 2016).

However, research findings on the role and effectiveness of online peer review on the quality of peer feedback and the subsequent text revision made have been mixed. Xu and Yu (2018) found that online peer review can offer Chinese-speaking students additional learning opportunities to negotiate meaning with their peers motivating them to continue giving feedback on both the structure and content of their L2 English writing. Similarly, Çiftçi and Kocoglu (2012) reported that L2 English students in Turkey who engaged in blog-based online peer review performed better on their second draft than those who completed traditional face-to-face peer review. However, students have been reported to prefer traditional face-to-face peer feedback when responding to comments on higher-order writing issues (e.g., Chen, 2012; Wu et al., 2015). Yu and Lee (2016, p. 46) note that a body of studies suggests that online peer review “does not necessarily increase students’ motivation, engagement, and autonomy.” Although online peer review has been observed to increase students’ engagement and enthusiasm for writing and revision, while facilitating the formation and transfer of students’ intrinsic motivation, and developing favorable attitudes toward revision (e.g., Jin & Zhu, 2010; Min, 2006; Yu & Hu, 2017), students’ perceptions toward online peer review are inconsistent (e.g., Guardado & Shi, 2007; Ho & Savignon, 2007). Guardado and Shi (2007), for example, in a Canadian university-level L2 English writing class, revealed students’ mixed feelings about conducting online peer review. They reported that many university students considered online peer-to-peer communication more challenging and problematic than face-to-face peer communication because it did not always promote negotiation of meaning among students. As a result, online peer review may be a unidirectional process of communication, with reviewers’ feedback being ignored or misinterpreted. Accordingly, how to enhance two-way peer dialogic communication using online tools appears to be a research area worthy of investigation. Specifically, empirical evidence is needed to demonstrate whether and how online peer review affords space for convenient bidirectional dialogue among peers compared with the unidirectional written form feedback often observed in conventional peer feedback (Nicol, 2010).

The present study

Despite the lack of empirical studies on facilitating L2 students’ text revision through online peer feedback while making revision plans through self-reflection, a few studies have explored peer feedback effects and suggested that online feedback may cultivate positive attitudes toward English writing and revision. However, there are some noticeable research gaps and limitations. First, research findings regarding the effectiveness and role of peer feedback for the improvement of text revision have indicated some links between the two. Still, the relevant findings are not consistent, which may be caused by various research designs. Few studies have applied exploratory qualitative instruments to investigate how L2 students learning English might benefit from online peer review and self-reflection on peer feedback. Second, studies investigating the effects of peer feedback on students’ revision behavior are primarily based on comparing researcher-coded peer feedback and revisions. However, it is unclear whether the researcher’s perspective accurately reflects the student’s view. Thus, by developing a coding worksheet for students to self-code peer feedback and match their codes with self-generated decisions for revision, the current study could provide new insights into this peer-mediated and self-reflective revision process from the student’s view. Further, this study expands on findings in the previous literature described by considering the significant underlying differences, perceptions, and experiences of L2 students during text revision processes. Individual L2 student needs to become more self-regulated to strategically use and reflect on peer feedback for text revision in order to develop comprehensive and robust L2 writing skills. The current study is guided by the following three research questions (RQs):

-

RQ1. What types and numbers of online peer feedback did students receive?

-

RQ2. How did students use online peer feedback in the text revision process?

-

RQ3. How did students perceive the benefits from involving in the peer-mediated revision process?

Method

The study was conducted in a first-year in-person course entitled “English Composition I” within an English-medium instructionFootnote 1 program (Bachelor of Arts in English Language Studies) at a research-intensive university in China. The focus of the course was to develop students’ basic English writing skills, such as sentence construction and style in narrative, descriptive, and persuasive essays. The course was taught by a Chinese-speaking instructor with a doctoral degree in English Education who had 20 years of experience teaching academic English writing. The study draws upon numerous sources of empirical data, including student writing and revision drafts, revision worksheets, and semi-structured interviews, to investigate the nature of text revision processes through online peer review.

Participants

Like many English language studies programs in Chinese universities, most of the students (around 18 years old) in the course were female (n = 16, 84%), with only three (16%) males. They were all native speakers of Mandarin Chinese and had learned English for at least 12 years. Their English scores ranged from 120 to 145 (upper-intermediate level across the country) out of a possible score of 150 in the entrance examination to Chinese universities. Their previous writing experience in English was confined to composing notices or short letters of around 150 words. Students used the QQ platform, a popular online interactive platform in China with more than 700 million active users in 2020 (Tencent, 2021), to seek and receive comments from peers who also enrolled in the writing class (see Procedures section). Twelve students (9 female and 3 male) who sought online peer feedback on the QQ platform after writing the first draft were recruited to complete the revision worksheet and allow the first author to collect their first and second writing drafts. All 12 students indicated their willingness to participate in a semi-structured interview with the first author to discuss their experiences with the revision process. Seven students who did not participate in the current study (i.e., who did not seek online feedback from peers) still needed to submit their first and second drafts to the writing instructor.

Procedures

Prior to the formal recruitment, the first author contacted the writing instructor and obtained permission to make an informal visit to the writing class to introduce himself, gave a short presentation about the research purposes and procedures, and observed the writing class. The primary goal of the fourth week’s writing class was to practice an essential genre in English writing: the persuasive essay. Prior to the writing phase, the instructor gave instructions on persuasive writing through close readings and in-class peer-to-peer discussion of how a model essay entitled “A noble career: Attorney” follows genre structure during the first hour of the class. In the second hour of the class, the writing instructor provided three more example essays from the previous writing cohorts asking students to identify writing problems in these essays and then helping them use the scoring rubric (see Measures section) to note specific content (global)- and language (local)-level features of Chinese university-level students’ English writing while trying to assess the three essays. Then, the students were required to spend thirty minutes writing an essay of about 200 words entitled “A career that I wish to pursue” in which they had to give detailed descriptions of an ideal career and explain why the career should be pursued. Students were given the option to type their essays or upload scanned versions of their hand-written essays. To keep the typed and handwritten conditions similar, students who typed the essay were not permitted to access any spell-checking, grammar-checking, or other word-processing resources. At the end of the class, students uploaded their first drafts to the group chat interface on the QQ platform.

After submitting the first drafts, students as authors can decide whether to seek and receive online peer feedback on the QQ platform asynchronously, and students as reviewers could provide oral or typed feedback on the private chat interface. Students self-initiated the feedback-seeking process so they knew the identities of the peers who provided the feedback, and they are able to ask clarifying or follow-up questions about the feedback provided. During the online peer interaction, students also could continue in-depth discussions in different ways, such as by offering further comments, providing additional writing sources, and clarifying and negotiating their English writing problems.

For those twelve students who had sought online peer feedback, they read and signed the consent forms distributed by the first author in-person and completed the revision worksheet (see Measures section), revised their first drafts, and submitted their revised drafts along with their revision worksheet to the first author and uploaded their revised drafts to the group chat interface on the QQ platform before the fifth week’s writing class. This gave the students one week to complete their revisions. Later, these students took about 20–30 min to participate in one-to-one in-person semi-structured interviews with the first author to talk about their experiences of the revision process.

Measures

In addition to student writing samples, the study included three instruments used for data collection: (1) a writing rubric, (2) a revision worksheet, and (3) a semi-structured interview. All of the instruments were developed or adapted by the first author and used for the first time in this study.

Writing rubric

The analytic writing rubric (see Appendix 1 for the full rubric) adapted from Li (2022b) was used in two ways in the current study. First, peers who were asked to provide feedback could use the writing rubric taught in the class to evaluate the persuasive essays. Second, it was used by the first author and a research assistant to assess students’ revision quality changes between drafts. The analytic rubric included four components:

-

Unity (how well students made a specific thesis statement or central argument and kept to it),

-

Support (how well the students’ writing provided evidence to support the main argument and the evidence is pertinent, typical, and appropriate),

-

Coherence (how well the students’ writing is structured and linked to the many pieces of evidence), and

-

Mechanics (how well students used English grammar, particular words, active verbs, and avoided slang, clichés, pompous language, and wordiness).

The rubric included a definition for each writing element, questions evaluators should ask themselves when scoring the element, and a scoring guide with a 1–7 scale (7 is the highest score). The scale included statements for each of the odd scores on the scale (i.e., 1, 3, 5, 7), and indicated that the even scores fell between each of the odd scores. Each dimension accounted for 25% of the overall writing score.

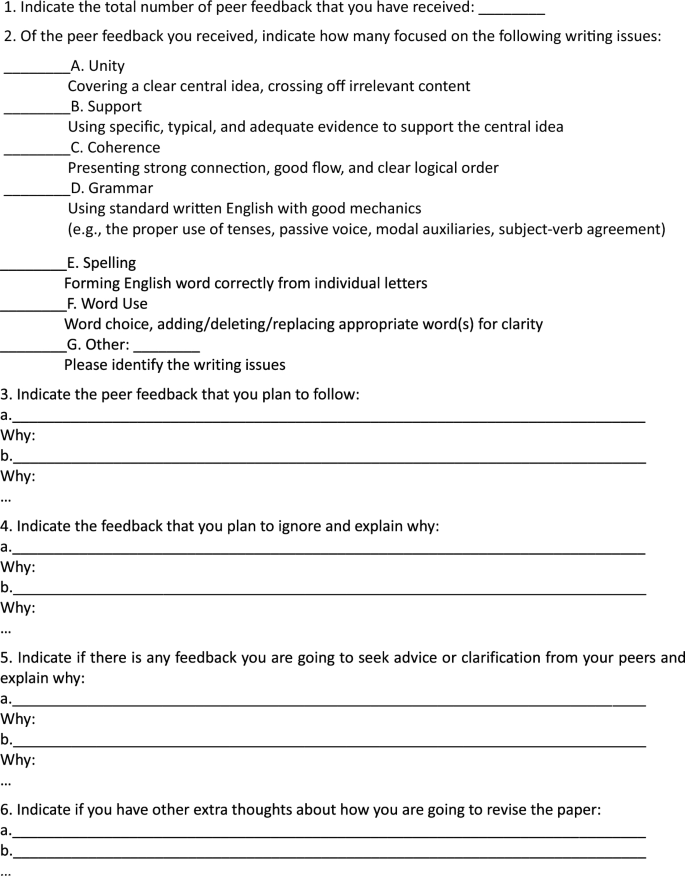

Revision worksheet

During the first draft revision activity, the participants were given a revision worksheet with six questions (see Appendix 2) developed by the first author to code the feedback they received from other students according to the coding scheme given on the revision worksheet; they then decided whether to follow or ignore the peer feedback, and finally generated a revision plan by answering the related questions. The revision worksheet guided participants in a structured thinking and reflection process to consider their goals and plan for revision. The worksheets were printed out and distributed to the participants. The participants took about 20–30 min to finish the revision worksheet. Students’ real names were replaced with pseudonyms after they submitted the worksheets.

Semi-structured interviews

The follow-up semi-structured interview questions (see Appendix 3) developed by the first author were used to explore students’ text revision process. Each interview, conducted in Mandarin with the first author, took about 20–30 min and was audio-recorded with permission. The participants commented on questions related to (1) their satisfaction with the revisions, (2) their challenges during the revision process, and (3) whether peer feedback, the QQ platform, and the revision plan helped them revise the draft. Participants responded to questions about whether they would continue to seek peer feedback, use the QQ platform, and draft revision plans in future L2 English writing and revision. The audio-recorded data were transcribed and translated into English by the first author after collecting all students’ data. The exact interview time and location were arranged at the student’s convenience. The full transcripts were then sent to the students to check the accuracy and clarity of the transcription. Two students made modifications to the interview content which were incorporated into the final version of the interview data.

Data collection and analysis

The study consisted of three data collection phases. The first phase consisted of draft writing and online peer review. In the second phase, the participants completed the revision worksheet and revision. The third phase was the interviews. Each phase took approximately one week.

To answer our RQs, we analyzed students’ first and revised drafts, writing performance between drafts, peer feedback during the online peer review activities, the revision worksheet, and the post-study interview transcripts. We first obtained students’ writing scores for the two drafts to examine the revision quality. The scores were generated from the mean value of two expert reviewers’ (i.e., the first author and a research assistant) ratings (afterward for the research study) on the writing rubric [rating Kappa (1st draft) = 0.93, Kappa (2nd draft) = 0.89] and we averaged the scores across raters to provide a final score and examine changes in scores from the first to second drafts. Each dimension accounted for 25% of the overall writing score. We then screened the worksheets to identify whether the participants had (1) coded the online peer feedback they received, (2) made decisions about whether to follow or ignore the online peer feedback, and (3) whether they elicited any revision goals and extra thoughts about the worksheet.

Students’ benefits and experiences from conducting online peer review on the QQ platform and using revision worksheets for self-reflections were obtained from the interview with the first author. The first author took the same writing course taught by the same writing instructor seven years ago and has taught college-level L2 writing in China and the USA, the participants seemed comfortable talking with the first author. The first author was an insider who could understand the students’ writing learning experiences but also an outsider with whom they could safely express their benefits and challenges when conducting online peer reviews and reflecting on the peer feedback.

The thematic analysis was applied to the semi-structured interview data by extracting themes (categories of benefits) from the interviews and triangulating views from all participants to clarify meaning and interpretation. The first author first synthesized all interview data to reveal themes related to RQ3. Later, relevant benefits in the interview data were coded for further patterning and clustering. The first author created new themes when the unit did not fit into any of the existing coding categories, and sub-categories were set when groups of data within a category could be classified. The coding process ended when all interview data units were assigned to one of the coding categories. The tentative coding scheme was also provided to a research assistant as a reference to ensure inter-coder reliability. This final revision coding scheme contains two major levels (social and cognitive) and four associated sub-benefits that were generated after analyzing the interview data is presented in Table 1. It was assessed for inter-rater reliability, producing strong Kappas on all.

Results and discussion

We begin with basic descriptive statistics regarding twelve students’ revision quality, i.e., the score improvements from the first to the second draft. A paired t-test (t(11) = 6.51, p < 0.000, Cohen’s d = 1.62) of paper ratings from the first to the second draft shows paper ratings improved by a mean of 1.1 points (out of 7), suggesting that the feedback led to students’ revisions produced meaningful improvements in the scores between drafts.

RQ1: What types and numbers of online peer feedback did students receive?

A total of 37 peer reviews were received and coded by the 12 participants into the six major writing issues. Three of these writing issues were higher-order content (global), i.e., unity, support, and coherence. The other three concerned mechanics, including grammar, spelling, and word use. Table 2 illustrates the types and frequencies of peer feedback. Among the six categories, the number of support-related peer feedback that the participants received was 37, which accounts for 100% (37/37) of the total. Coherence-related peer feedback came second (83.8%, 31/37) followed by unity (78.4%, 29/37).

As for low-level writing issues, most peer feedback focused on grammar (73.0%, 27/37) followed by word use (64.9%, 24/37) and spelling (32.4%, 12/37). Thus, peer feedback focused more on higher-order writing issues than lower-order language use. Unlike previous studies (e.g., Leki, 1990; Tsui & Ng, 2000), where L2 students’ peer feedback heavily focused on surface concerns, such as word use, grammar, spelling, and punctuation, while neglecting macro-level content-related writing issues, the feedback in the present study covered global aspects, such as content, organization, and logic in alignment with Min (2006) and Yang et al. (2006). This is likely attributable to the pre-writing training. As revealed by some studies (Min, 2006; Min & Chiu, 2021), students who are given peer feedback training are inclined to provide and receive more feedback focusing on organization, content, and logic (global areas) rather than grammar, word use, or spelling (local areas). From the first class of the academic English writing course, the instructor started to train students through in-class peer-to-peer discussion to identify both higher- and lower-level writing issues, which could be found in the sample essay shown to the students. Thus, students received peer feedback that covered all six writing issues.

In addition, the affordance of online communication on the QQ platform rather than written marginalia on the hardcopy of their essays might have enabled students to pay more attention to higher-ordered English writing issues (Patchan et al., 2013). Specifically, students are likely to receive detailed low prose peer feedback that focuses on grammar, word use, or spelling problems when their peers write marginalia on their essays, or in Lee’s (2019) words, the written feedback/commentary usually target lower-level writing issues such as grammar correction and “make the paper flooded with the red ink” (p. 524). While in the current study, the QQ platform provided an interactive communication space that enabled students to read and evaluate their peers’ essays online and then type/record peer feedback at the bottom of the individual chat box, which may also encourage students to provide more feedback on the global aspects of writing such as contents, organization, and logic when communicating with peers.

Six of the 12 participants coded nine other types of peer feedback, which accounted for 21.6% (9/37) of the total peer feedback received. Among this feedback, two comments focused on enhancing students’ handwriting, and the other seven were categorized as sentence skills concerning the extensive and effective use of sentences. The writing instructor gave instructions on sentence skills using College writing skills with Readings (Langan, 2011) as the required textbook at the beginning of the course so that students would (1) write complete sentences rather than fragments; (2) avoid run-on sentences; and (3) use various sentence patterns. Thus, it was unsurprising to see students receive such peer feedback, although they had learned and practiced these sentence skills since high school.

RQ2: How did students use online peer feedback in the text revision process?

Online peer feedback to follow

Support

The third question of the revision worksheet generated data revealing that all students decided to take actions based on the support-related peer feedback. When answering the sixth question regarding students’ other thoughts for revision, all students claimed that the support dimension (see Table 3 for examples), i.e., adding supporting evidence to enrich the content, is important.

Deciding to follow peer feedback on specific writing issues does not always mean that students will finally take action to implement those peer feedback into their revisions (Lam, 2021; Zhang et al., 2017). By comparing their first and second drafts, it was found that all students incorporated support-related peer feedback and made substantial revisions in their second drafts, which aligns with Baikadi et al.’s (2015) finding that students reflect on content-level peer feedback such as adding more supporting details are more likely lead to text revisions. As Table 4 illustrates, students revised their support problems by adding more details, examples, and evidence to support their central arguments.

Grammar

All students decided to follow grammar-related peer feedback. Students listed the reasons in the worksheet why these comments were helpful (see Table 5 for examples).

Students believed these grammar-related problems needed to be revised because writers may fail in their primary purpose of writing and lose the readers’ interest (Zelda, Julia). Therefore, such low-level grammatical problems that their peers mentioned were revised (Zoe, Lisa, Mike, Milton). They also believed that paying attention to low-level writing issues could make their second draft error-free (Tina, Helen,) clearer, and more idiomatic (Lisa,) without taking much time (Julia).

Areas where participants revised included: singular and plural, questioning, non-finite verbs, adverbs, and subject-verb agreement (see Table 6). In sum, participants decided to follow and incorporate both higher- and lower-order peer feedback into their second draft and revise the writing issues, especially regarding support, coherence, grammar, and spelling. Contrary to the conclusions drawn from other empirical studies (e.g., Cho & MacArthur, 2010; Min, 2006) which found that students tended to act on micro-level language issues from their peers and make only low-level revisions on their second drafts, this finding indicates that students could identify and balance both higher-order content and low-level language issues upon receiving peer feedback and make decisions based on their self-reflections on peer feedback for further revision planning.

Online peer feedback to ignore

Four students ignored unity-related peer feedback, while two ignored word-use-related peer feedback. Their reasons are presented in Table 7.

As the above students wrote, they used several negative expressions like “I do not think…”, “I do not agree with peer comment…”, “I disagree with my peers”, “… is not off-topic”, “without irrelevant details”, “I am sorry…”, and “I will ignore this comment” to show disagreement and their decisions to ignore peer feedback. The finding echoes previous studies (e.g., Baikadi et al., 2015; Guardado & Shi, 2007) that individual L2 students tend to generate decisions/actions to ignore peers’ comments that conflict with their own when revising a second draft.

Online peer feedback requires further advice and clarification

Support

During the interviews, three of the participants said that support-related issues were easy to revise. However, seven students said they were not because some peers’ feedback was too vague. Yara felt lost when reading peer feedback and said:

Some peers mentioned on QQ that I should provide more detailed content to make my essay clearer, but I did not know how to revise the support-related writing problems because they did not provide me with some specific suggestions, and they didn’t specify which paragraph or sentence I should focus on revising. (Yara, InterviewFootnote 2)

Like Yara, some students were struggling with the question of how to revise. For example, Mercer said he wrote a very concise first draft about the career of a network writer. One of his peers suggested that he should add more details to enrich the content and support his central argument. However, he felt confused because he did not know how to enrich the content. Thus, he indicated on the review worksheet that he needed further advice and clarification:

I don’t know how to revise to make my content richer. Their comments are too general. Shall I simply add numbers to provide the salary of the job? Or should some specific examples be given? Adding too many details will make it become wordy and hard to understand, but my essay will become more persuasive to some degree. (Mercer, Revision Worksheet)

Finally, Mercer accepted this suggestion and added details to support his central argument. Furthermore, he mentioned he double-checked with two peers by sending revised drafts to them and continued the conversation after revising the drafts on the QQ platform.

In contrast to Mercer, Julia’s response was quite different when facing the same problem. She wrote on the revision worksheet:

My peers pointed out that the effects and meaning of being a teacher should be provided to support my major argument - Being a teacher is an attractive career for us to pursue, but this peer comment is very general. So, I am not sure how to revise it. (Julia, Revision Worksheet)

Julia also indicated that revising support-related issues was difficult because she thought her peers’ comments were too general and hard to follow. However, she found some model essays and relevant news from the internet as references. In the end, Julia was still dissatisfied with the revised draft, and she found more information online and wrote a third and a fourth draft.

Coherence

Four students claimed that coherence-related writing issues were difficult to revise, and they sought further suggestions. For example, Yara said:

Coherence-related writing issues in my essay are very difficult to revise because I am not sure how to make my writing more coherent and idiomatic by simply reading my peers’ comments. It is very easy for my peer to say that I have coherence-related problems because our English writing is not perfect. But I just felt very confused because what I really want is more specific suggestions. (Yara, Interview)

When asked to provide more details, Yara explained that one peer suggested that some sentences lacked coherence and needed improvement. Nevertheless, Yara complained that she had no idea which sentences had problems, and thus did not know how to revise them to improve coherence. Therefore, she sought advice and clarification with their peers who provided the original comments on the QQ platform by sending the revised draft to them. In the end, her peers agreed that the revised version was improving, and Yara was delighted to see her writing improve on coherence-related issues with her peers’ help.

Word use

Regarding low-level writing issues, three students argued that word use-related peer feedback was difficult to follow. During the interviews with Tina and Julia, they said:

I felt helpless when reading word-use-related peer feedback, and I thought my word usage was good in the first draft. I think they can provide more specific comments to help me revise my essay. I was not sure whether they meant that the use of the word – “Australian” was wrong in my essay. (Tina, interview)

My peers’ comments on the word-use writing issues are too general to follow. I understand I had some problems or used some words wrongly in my first draft. But what confused me was that I had no idea which word was used incorrectly. I need more peers to help me find my problems. (Julia, Interview)

Tina decided to double-check with peers on the QQ platform and ask them why they provided these comments. After discussing with peers, she found that the word “Australian” (people) should be “Australia” (country), and she successfully revised the sentence. Unlike Tina, Julia re-read her essay and used the e-dictionary to check the usage of some words like “elect” in the essay and found that it could be replaced by another phrasal verb “search for” to make the essay clearer. Julia’s learning experience with the word use-related writing issue also echoed her decision to use the internet to solve support-related writing issues.

Other—sentence skills

Three students also indicated that they wanted further advice and clarification on some peer feedback regarding sentence skills. For example, Mike received one peer comment which suggested that one sentence should be revised using another expression because it sounded too passive. However, he was not sure which expression was better. Then he discussed with the peer who provided the comment and finally replaced “if I got to” with “when it comes to” in the second draft. Mike commented:

This mutual online learning process is very critical to my learning of English writing, and I benefited a lot. Although some peer feedback I received is quite general, and I was unsure how to revise it, I negotiated this issue with my peers on the QQ platform. And to my big surprise, my peers were very kind, patient, and willing to continue the conversation with me. I feel very grateful to them. (Mike, Interview)

Peer feedback can be either general or contradictory (two peers conflicting) among multiple peer reviewers (Baikadi et al., 2015; Patchan et al., 2013). One peer suggested that Rose should change one long sentence to two short sentences because the long sentence was difficult to understand; however, another peer praised her because she used some complex sentence structure correctly in her long sentence. Rose felt confused and said:

Interestingly, I received contradictory peer feedback on one writing issue – sentence skills. I found it is really hard to make a decision based on reading my peers’ comments. So, I checked it with the online software called Grammarly on my phone, and it highlighted the sentence as “hard-to-read” because “an expert audience may find this sentence … not clear.” I finally split it into two sentences. (Rose, Interview)

This illustrates how Rose decided with the help of Grammarly to gather helpful feedback on sentence structure for better text revision after reflecting on contradictory peer comments. Echoing previous studies (e.g., Chang, 2015; Ho & Savignon, 2007; Lam, 2021), unlike traditional face-to-face peer review, online technologies play an affordance role in permitting students to gather new information. For example, the QQ platform used in the current study could permit students to continue the private conversation with their peers in either written or oral forms, and the Grammarly software could assess the issues of grammar, word use, and sentence structure of their academic writings, which can increase the quality and volume of feedback that student received. Such timely and thorough revision suggestions are less likely can be provided by individual writing instructors.

The analyses in this section demonstrated that each L2 student might have different action/decision-making paths toward second draft writing triggered by different types of online peer feedback received and revision planning from self-refection. More importantly, students could strategically fix higher- and lower-order writing issues by experiencing one or more rounds of social learning processes mediated by peers in the online technology or other social agents existing in their academic English learning environments.

RQ3. How did students perceive the benefits of the peer-mediated revision process?

Social-level benefits

The first social-level benefit that all students mentioned during the interview is that peers in the online social environment could provide new insights from various perspectives. For example, Yara said:

My peers have different perspectives and standards when evaluating my writing, so I can understand what different peers think about my writing. I may face a situation where I do not know how to revise, so peer feedback offers me fresh thoughts and solutions from various perspectives. I think this social learning process with my peers is an excellent way to improve my English writing skills. (Yara, Interview)

Students also mentioned that their peers’ perspectives were as important as their instructors’ comments whose time and help are limited (e.g., Tina, Rose). Students like Zoe and Zelda indicated that having peers evaluate their essays was better than self-revision without peer and instructor support.

Furthermore, some students expressed a positive attitude toward conducting peer review because they enjoyed hearing their peers’ “new” (Yara), “different” (Helen), “unique” (Rose), and “interesting” (Zelda, Zara) viewpoints. “The more [peer] feedback, the better,” said Tina. Zoe used a Confucian proverb “Among any three people walking, I will find something to learn.” to appreciate her peers’ comments. Revising with peer feedback, students found that their second draft was becoming better. Some confirmed that they needed their peers to view their essays from a new perspective (Helen, Zara) and expressed their willingness to find different peers to provide feedback in the future (Lisa, Zoe).

The second social-level benefit that seven students articulated is that using the interactive technology (the QQ platform) could encourage them to initiate several rounds of social self-regulation by discussing, clarifying, and negotiating writing issues with their peers. For example, when reading peer feedback, Mercer commented:

After reading peer feedback, I was unsure how to revise and wanted to explain my thoughts to peers. So I sent some voice messages to my peer, who provided feedback on the QQ platform and we discussed different writing issues again. For me, the peer review never ends because the casual chat with peers on my writing is not confined by time and space. I really like the way we talk about writing learning, and I finally revised my writing problems and really benefited from the online discussion with my supportive classmate. (Mercer, Interview)

Similarly, Lisa felt social interaction with peers on the QQ platform was enjoyable and would continue to practice revisions by continuing the conversation with those peers who provided feedback in the future. Zara, Mike, and Rose also believed that peers on the QQ platform helped them make decisions and generate a more workable plan for the second draft. Mike said:

The QQ platform allows me to continue talking about my writing with peers who provided feedback through private chat. After discussing with my peers, I clarified my thoughts and deepened my understanding of English writing issues. (Mike, Interview)

Cognitive-level benefits

The first cognitive-level benefit that many students referred to is that using the revision worksheet could obtain opportunities to reflect on their peers’ comments and find solutions for revision. For example, Julia explained:

This worksheet helps me deeply understand my peers’ feedback through self-reflection, and it assists me in finding the highlighted and valuable parts of peer feedback. I also clarified my logic and made final decisions for the second draft writing. This process makes my essay more readable and persuasive. With this worksheet in hand, I can revise my essay quickly and effectively with great concentration. (Julia, Interview)

The second cognitive-level benefit is that peers offered emotional support to their English writing with constructive feedback and praise. Five students used expressions like “grateful,” “quite hopeful,” “delighted,” “more interested,” “inspired,” “highly inspired,” “glad,” “happy,” “very happy,” “really happy,” “being encouraged,” and “feel encouraged” to describe their peers’ comments which inspired them to make significant revisions on both high- and low-level writing issues. For example:

My peers read my first draft word by word and found some grammar- and word use-related writing problems. Some peers’ comments are special and advanced. So, I feel very grateful and accepted their suggestions immediately. I am quite hopeful about my English writing learning. (Julia, Interview)

The present findings align with previous observations that online peer review brings new insights from multiple reviewers (e.g., Liu & Carless, 2006; Yu & Hu, 2017) and provides scaffolds for peer reviews such as timely feedback, negotiation of meaning, and interactive discussion of writing issues (e.g., Lam, 2021; Lu, 2016; Yu & Lee, 2016). More importantly, the current research also revealed that online peer feedback contributes to students’ positive emotions toward peer review and triggers a further use of sources from the social-learning environment. The findings highlight how self-reflection and action planning are critical factors affecting L2 students’ writing learning process (Alitto et al., 2016; Jin & Zhu, 2010; Zhang et al., 2017).

The findings suggest that the revision worksheet, which required students to document their self-reflections, provided opportunities to analyze the direct connection between students’ self-reflection and revision planning from the online peer review and subsequent text revision processes. However, this study has not established a causal role of students’ self-reflections. This concern is mitigated, though, by the consistent findings in the literature that providing reviews does develop students’ writing performance (e.g., Lee, 2019; Liu & Carless, 2006; Patchan et al., 2013). A related concern may be raised about the addition of the documentation tool: requiring students to explicitly document their self-reflections may have changed the number or rate at which they followed up on their text revisions. Yet analyses reported elsewhere suggest that this is not the case (e.g., Baikadi et al., 2015; Lam, 2021; Zhang et al., 2017), i.e., students using introspective tools made no more revisions than students who did not use those tools when writing a second draft. Thus, the primary effect of introspective tools like the revision worksheet designed in the study appears to illuminate student cognition and cognitive self-reflective process.

Conclusion and implications

This exploratory study has shown that seeking and receiving online peer feedback and reflecting on feedback by drafting a revision plan are useful socio-cognitive learning sources that can shape students’ L2 English persuasive essay revision behavior. The semi-structured interview data further demonstrated how students perceived the social- and cognitive-level benefits from the peer-mediated and self-reflective process of revision in persuasive writing. The study has significant pedagogical implications for L2 English writing instructors at Chinese universities and beyond. In many L2 English writing classrooms in China, there are few teaching and learning resources, so L2 learners complete two to three years of writing learning and practices without a good understanding of how to develop basic English writing skills (e.g., unity, support, coherence, and mechanics), and their learning-to-write process is often self-directed with less effective guidance or instructional intervention. This negatively impacts students’ academic and professional success, which, to a great extent, depends upon their writing skills.

Socio-cognitive learning strategies (i.e., seeking and self-reflecting online peer feedback) are beneficial for enabling students to use the various learning resources in the larger socio-environmental context of L2 English persuasive writing. Thus, writing instructors should consider asking students to seek and receive online peer feedback and utilize the revision worksheet outlined in this study for multi-draft persuasive writing assignments. Compared to traditional instructor-centered writing pedagogy, seeking and reflecting peer feedback are student-centered processes. As students experience such processes, they develop an understanding of fundamental L2 English writing issues raised by peer feedback and establish a basis for self-reflection and finally enhance their writing performance across drafts and genres.

Naturally, the role of the writing instructor should not be diminished in peer-mediated revision processes. Rather, they are more like directors behind the stage. The writing instructors should provide clear writing prompts, and clear review rubrics with writing models, while giving students training on how to conduct online peer reviews and offering effective feedback. Playing the role as a facilitator, writing instructors can foster students’ micro-process development in English writing skills and domain knowledge, implementing non-threatening practices that encourage students to face challenges and interpret errors as opportunities to learn (Li & Zhang, 2021; Li, 2022a; Yu & Hu, 2017). Socio-cognitive learning sources such as peer feedback and revision planning serve as essential assistance while instructors provide further practical guidance. For example, revision plans may be combined or integrated with instructors’ and students’ assignment expectations. Writing instructors can use students’ coding and planning worksheets as references to better understand students’ needs and facilitate their writing self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation.

Further, online learning tools can reduce the logistics involved in sending and receiving documents, strengthening the connections between students in a shared learning community and supporting the sustainable development of writing with multiple drafts and peer review. The group chat interface on the QQ platform can be quickly established in large classes if students have an internet-enabled phone or computer access. Online tools may also be more convenient for instructors because they offer many digital advantages over paper.

Limitations and future research

The current study has several limitations. First, the participants were confined to a narrow context, procedure, and level (i.e., they are Chinese-speaking students who took an in-person English-taught first-year L2 writing class at a northeastern-Chinese university, conducted online asynchronous peer reviews using the QQ platform, wrote and revised persuasive writing in the fourth week’s class, it cannot be generalized to other contexts). Thus, the current approach could be replicated with other kinds of writing assignments and genres, different kinds of peer review rubrics, and students of different writing levels and schools to explore whether L2 English students’ self-reflective processes in response to peer feedback generate similar findings. Other approaches to document students’ self-reflective processes in response to peer feedback should also be explored to maximize efficiency and validity. For example, future research could use an experimental design with a control group (i.e., writing instruction with self-reflection on peer feedback, writing instruction with different revision worksheets for self-reflections), so documenting revision planning by self-reflecting peer feedback could be controlled carefully, and causal claims could be supported. Nevertheless, as students’ mental processes when reading peer feedback are difficult to capture in authentic classroom contexts, the current exploratory study seems to represent a step forward. Thus, future in-depth case study design with different L2 writing learning contexts are also suggested.

Since the present revision worksheet may have under-reported students’ thoughts, techniques such as think-aloud during reviewing may provide better records. Similarly, the use of self-regulation strategies during revision (especially including self-editing) could have been observed more directly if students had been observed or if they had recorded their screens during their revision process. Students could also have been asked to name other input resources, such as their use of the writing center or outside-of-class friends and materials, which again may be considered in future research.

Further, the revision worksheet, although efficient in collecting students’ self-coded peer feedback and documenting their reflective thinking, may have made students more aware of their thinking and planning processes, i.e., it may have stimulated students’ metacognitive awareness of writing and revision, and thus influenced the data. Future studies should explore how revision worksheets can be used as an intervention tool to improve students’ engagement in the metacognitive self-regulation process.

Peer review can be an essential channel for the training of reflective thinking, which is a core component of the self-regulated learning process. Peer review requires students to sift through information and materials, determine what is relevant and redundant, comment on what is understood, and uncover directions for skill development, all core skills in critical thinking development. Undergoing this peer review process in L2 academic writing, students can become more effective writers by deepening engagement and positive associations with other students. Investigating students’ reflective thinking development using online peer feedback in L2 academic writing is thus valuable for ongoing research.

Availability of data and materials

We confirm that the data supporting the findings are available within this article. Raw data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Notes

Instructors use the English language to teach academic subjects in countries or jurisdictions where the first language of the population is not English.

Note that the interview data is translated from Mandarin Chinese to English.

References

Alitto, J., Malecki, C. K., Coyle, S., & Santuzzi, A. (2016). Examining the effects of adult and peer mediated goal setting and feedback interventions for writing: Two studies. Journal of School Psychology, 56, 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.03.002

Baikadi, A., Schunn, C., & Ashley, K. (2015). Understanding revision planning in peer-reviewed writing. Paper presented at the 8th international conference on educational data mining. Madrid, Spain.

Berggren, J. (2015). Learning from giving feedback: A study of secondary-level students. ELT Journal, 69(1), 58–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccu036

Chang, C. Y. (2015). Teacher modeling on EFL reviewers’ audience-aware feedback and affectivity in L2 peer review. Assessing Writing, 25, 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2015.04.001

Chen, K.T.-C. (2012). Blog-based peer reviewing in EFL writing classrooms for Chinese speakers. Computers and Composition, 29(4), 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2012.09.004

Cho, Y. H., & Cho, K. (2011). Peer reviewers learn from giving comments. Instructional Science, 39(5), 629–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-010-9146-1

Cho, K., & MacArthur, C. (2010). Student revision with peer and expert reviewing. Learning and Instruction, 20(4), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.006

Ciftci, H., & Kocoglu, Z. (2012). Effects of peer e-feedback on Turkish EFL students’ writing performance. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 46(1), 61–84. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.46.1.c

Duijnhouwer, H., Prins, J., & Stokking, K. (2010). Progress feedback effects on students’ writing mastery goal, self-efficacy beliefs, and performance. Educational Research and Evaluation, 16(1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611003711393

Flower, L. (1994). The construction of negotiated meaning: A social cognitive theory of writing. Southern Illinois University Press.

Graham, S., & Alves, R. A. (2021). Research and teaching writing. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 34, 1613–1621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10188-9

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 445–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.445

Graham, S., Hebert, M., & Harris, K. R. (2015). Formative assessment and writing: A meta-analysis. The Elementary School Journal, 115(4), 523–547. https://doi.org/10.1086/681947

Guardado, M., & Shi, L. (2007). ESL students’ experiences of online peer feedback. Computers and Composition, 24(4), 443–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2007.03.002

Harris, K. R., Ray, A., Graham, S., & Houston, J. (2019). Answering the challenge: SRSD instruction for close reading of text to write to persuade with 4th and 5th grade students experiencing writing difficulties. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 32, 1459–1482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9910-1

Ho, M., & Savignon, S. (2007). Face-to-face and computer-mediated peer review in EFL writing. CALICO Journal, 24(2), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v24i2.269-290

Jin, L., & Zhu, W. (2010). Dynamic motives in ESL computer-mediated peer response. Computers and Composition, 27(4), 284–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2010.09.001

Lam, S. T. E. (2021). A web-based feedback platform for peer and teacher feedback on writing: An activity theory perspective. Computers and Composition, 62, 102666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2021.102666

Langan, J. (2011). College writing skills with readings. McGraw-Hill Education.

Lee, I. (2019). Teacher written corrective feedback: Less is more. Language Teaching, 52(4), 524–536. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444819000247

Leki, I. (1990). Coaching from the margins: Issues in written response. In B. Kroll (Ed.), Second language writing (pp. 57–68). Cambridge University Press.

Li, W. (2022b). Scoring rubric reliability and internal validity in rater-mediated EFL writing assessment: Insights from many-facet Rasch measurement. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 35, 2409–2431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10279-1

Li, A. W. (2023). Using Peerceptiv to support AI-based online writing assessment across the disciplines. Assessing Writing. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2023.100746

Li, W., & Zhang, F. (2021). Tracing the path toward self-regulated revision: An interplay of instructor feedback, peer feedback, and revision goals. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 612088. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.612088

Li, L., Liu, X., & Steckelberg, A. L. (2010). Assessor or assessee: How student learning improves by giving and receiving peer feedback. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(3), 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.00968.x

Li, W. (2022a). Exploring revision as a self-regulated process in EFL writing. Unpublished M.A. thesis, University of British Columbia. https://doi.org/10.14288/1.0407287.

Liu, N., & Carless, D. (2006). Peer feedback: The learning element of peer assessment. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(3), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510600680582

Lu, J. (2016). Student attitudes towards peer review in university level English as a second language Writing classes (Unpublished M.A. thesis). St. Cloud State University.

Lundstrom, K., & Baker, W. (2009). To give is better than to receive: The benefits of peer review to the reviewer’s own writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18, 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2008.06.002

Min, H. T. (2006). The effects of trained peer review on EFL students’ revision types and writing quality. Journal of Second Language Writing, 15, 118–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2006.01.003

Min, H. T., & Chiu, Y. M. (2021). The relative effects of giving versus receiving comments on students’ revision in an EFL writing class. English Teaching and Learning, 46, 293–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-021-00094-2

Nicol, D. (2010). From monologue to dialogue: Improving written feedback processes in mass higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602931003786559

Papi, M., Bondarenko, A. V., Wawire, B., Jiang, C., & Zhou, S. (2020). Feedback-seeking behavior in second language writing: Motivational mechanisms. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 33, 485–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-019-09971-6

Patchan, M., Hawk, B., Stevens, C. A., & Schunn, C. D. (2013). The effects of skill diversity on commenting and revisions. Instructional Science, 41(2), 381–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-012-9236-3

Tencent. (2021). Tencent. Retrieved from https://www.tencent.com/en-us/index.html.

Trautmann, N. (2006). Is it better to give or to receive? Insights into collaborative learning through web-mediated peer review (Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation). Cornell University.

Tsui, A. B. M., & Ng, M. (2000). Does secondary L2 writers benefit from peer comments? Journal of Second Language Writing, 9, 147–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1060-3743(00)00022-9

van Velzen, J. H. (2002). Instruction and self-regulated learning: Promoting students’ (self-) reflective thinking. (Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation). Leiden University.

Wu, W. C. V., Petit, E., & Chen, C. H. (2015). EFL writing revision with blind expert and peer review using a CMC open forum. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.937442

Xu, Q., & Yu, S. (2018). An action research on computer-mediated communication (CMC) peer feedback in EFL writing context. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 27(3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0379-0

Yang, Y. (2010). Students’ reflection on online self-correction and peer review to improve writing. Computers and Education, 55(3), 1202–1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.05.017

Yang, M., Badger, R., & Yu, Z. (2006). A comparative study of peer and teacher feedback in a Chinese EFL writing class. Journal of Second Language Writing, 15(3), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2006.09.004

Yu, S., & Hu, G. (2017). Understanding university students’ peer feedback practices in EFL writing: Insights from a case study. Assessing Writing, 33, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2017.03.004

Yu, S., & Lee, I. (2016). Peer feedback in second language writing (2005–2014). Language Teaching, 49(4), 461–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2017.03.004

Zhang, F., Schunn, C. D., & Baikadi, A. (2017). Charting the routes to revision: An interplay of writing goals, peer comments, and self-reflections from peer reviews. Instructional Science, 45(5), 679–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-017-9420-6

Zhang, F., Schunn, C. D., Li, W., & Long, M. (2020). Changes in the reliability and validity of peer assessment across the college years. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(8), 1073–1087. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1724260

Zhang, F., Schunn, C. D., Chen, S., Li, W., & Li, R. (2023). EFL student engagement with giving peer feedback in academic writing: A longitudinal study. Journal of English for Academic Purposes. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2023.101255

Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (2002). Acquiring writing revision and self-regulatory skill through observation and emulation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 660–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.660

Zumbrunn, S., Marrs, S., & Mewborn, C. (2016). Toward a better understanding of student perceptions of writing feedback: A mixed methods study. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 29, 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9599-3

Acknowledgements

We thank the guest editor, Steve Graham, who provided valuable suggestions that facilitated our revisions. We are also grateful to Ling Shi, Paul Stapleton, Ann Anderson, and two anonymous reviewers for their detailed and incisive comments on an earlier draft of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

We confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

Ethical approval

This study obtained ethics approval from the University of British Columbia’s Behavioral Research Ethics Committee (Human Ethics Certificate # H21-00163). All methods performed in the study were carried out in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

The analytical rubric for persuasive writing

Unity | Definition | Covering a clear central idea, no irrelevant content | |

Questions | 1. Does the essay have a clearly stated thesis? | ||

2. Is there any irrelevant material that should be eliminated or rewritten? | |||

Scoring guide | 7 | Very clear thesis statement, no irrelevant content | |

6 | Between 7 and 5 | ||

5 | Clear thesis statement with some irrelevant content | ||

4 | Between 5 and 3 | ||

3 | Vague thesis statement with many irrelevant | ||

2 | Between 3 and 1 | ||

1 | Off-topic | ||

Support | Definition | Using specific, typical, and adequate evidence to support the central evidence | |

Questions | 1. Has the writer backed up each main point with one extended example or several shorter examples? | ||

2. Does the writer have enough detailed support? | |||

Scoring guide | 7 | The supportive detail is very pertinent, typical, and appropriate | |

6 | Between 7 and 5 | ||

5 | The supportive detail is pertinent, typical, and appropriate | ||

4 | Between 5 and 3 | ||

3 | The supportive detail is not very pertinent, typical, and appropriate | ||

2 | Between 3 and 1 | ||

1 | Little supportive detail | ||

Coherence | Definition | Presenting strong connection, good flow, good transitions, and clear order | |

Questions | 1. Has the writer used transition words to help readers follow the train of thought? | ||

2. Has the writer provided a concluding paragraph to wrap up the essay? | |||

Scoring guide | 7 | Sentences are tightly connected, with good transitions and a clear order | |

6 | Between 7 and 5 | ||

5 | Sentences connect with each other, although the sentence order is not very clear | ||

4 | Between 5 and 3 | ||

3 | Sentences are loosely connected, with a few disordered sentences and ideas | ||

2 | Between 3 and 1 | ||

1 | No flow | ||

Mechanics (grammar, spelling, and word use) | Definition | Grammar | Using standard written English (e.g., tenses, passive voice, and modal auxiliaries) |

Spelling | Forming English word correctly from individual letters | ||

Word use | Word choice, adding/deleting/replacing appropriate word(s) for clarity | ||

Questions | Grammar | Has the writer avoided grammatical errors? | |

Spelling | Has the writer avoided spelling errors? | ||

Word use | 1. Has the writer used specific rather than general words? | ||

2. Has the writer avoided wordiness and been concise? | |||

Scoring guide | 7 | The low-level dimensions are used very effectively | |

6 | Between 7 and 5 | ||

5 | The low-level dimensions are used effectively | ||

4 | Between 5 and 3 | ||

3 | Most of the low-level dimensions are used correctly | ||

2 | Between 3 and 1 | ||

1 | The low-level dimensions are used incorrectly | ||

Appendix 2

Revision worksheet

This worksheet helps you to plan your first draft revision. Please code and summarize the peer feedback you have received by answering the following questions. The planning process should take about 10–20 min. You can then follow the plan to revise your essay.

Appendix 3

Interview guidelines

-

1.

Are you satisfied with the revised second draft? And why?

-

2.

What are the easy parts to revise in the essay? Are there any challenges when revising the essay?

-

3.

Did peer feedback help you revise? If so, in what ways?

-

4.

Did the revision worksheet help you revise? If so, in what ways?

-

5.

Are you willing to continue using peer feedback and drafting a revision plan in the future?

-

6.

What have you learned from the revision process?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, A.W., Hebert, M. Unpacking an online peer-mediated and self-reflective revision process in second-language persuasive writing. Read Writ 37, 1545–1573 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-023-10466-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-023-10466-8