Abstract

This study examined the effects of a classroom-focused intervention on different domains of early literacy. The intervention consisted of shared e-book reading combined with a print referencing technique done via a SMART board. The specific goal of the study was to examine whether children could be instructed simultaneously in print knowledge, phonological awareness, and vocabulary, without a loss of impact on the development of either skill. Results revealed significantly larger gains with high effect sizes in print knowledge (ηp2 = .474) and phonological awareness (ηp2 = .370) when children received the print referencing e-book intervention compared to the control conditions. Print referencing did not hinder children’s learning of new words, but enhanced vocabulary to the same extent, or even higher, as e-books typically do in kindergarten when print referencing is not involved. The findings indicate that e-book reading merged with print referencing is a beneficial method for enhancing essential early literacy skills simultaneously. The learning tool is particularly efficient for a tailor-made educational setting, as it allows differential attention to students and lessens the workload for teachers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Early education experiences provide children with opportunities to develop the prerequisite knowledge and skills in literacy that reliably translate into later school success (Burchinal et al., 2002; Inoue et al., 2018). Many children are at risk for reading problems because of inadequate emergent literacy skills. It is therefore necessary to give high-quality evidence-based emergent literacy instruction during the critical developmental period of early childhood. The different domains of early literacy appear to be responsive to different types of instructional activities. It would however be efficient to expose children to a single training to enhance all essential emergent literacy skills at once, without a loss of impact on the development of either skill. The present study examines the feasibility of a combined instruction to teach print knowledge, vocabulary and phonological awareness.

Shared book reading is a widely recommended activity for promoting children’s language and literacy skills. Shared book reading refers to the interactions and discussions that occur when adults and children read a book together, and is particularly effective for literacy development (Mol et al., 2009). Both, the frequency of shared reading and extratextual conversations beyond reading the text, are predictive of growth in code related skills and oral language (Zucker et al., 2013). Extratextual conversations to increase emergent readers’ print knowledge is known as print referencing, an evidence-based technique using verbal (e.g., ‘this is the letter M, it sounds like mmm’) and nonverbal (e.g., pointing to text) cues to call attention to printed matters during classroom-based storybook reading sessions (Justice & Ezel, 2002, 2004; Justice et al., 2009).

Conventional storybook reading in classrooms has its limitations. In large groups, few children are able to see the text supporting pictures well enough to scaffold word learning. Extra textual code-related talk is only possible with storybooks containing print salient features and interrupts the story line significantly. Likewise, phonological awareness utterances will interrupt the storyline. In addition, a lesser time-consuming nonverbal shift of focus on print, is restricted to pointing with the finger. Finally, a print referencing style is not naturally used by adults when reading with children (Justice et al., 2009). The use of e-storybooks and interactive whiteboards can make print referencing easier to implement.

E-storybooks are electronic forms of a traditional print book and offer, in addition to the text and pictures in the paper version, digital features that can assist the reader (de Jong & Bus, 2004; Korat & Shamir, 2004). E-storybooks can be more beneficial to literacy development than traditional storybooks (de Jong & Bus, 2003; López-Escribano et al., 2021; Savva et al., 2021). The digital features built into e-books can enhance children’s motivation (Smith, 2012) and draw their attention towards important aspects of print or story elements, thereby providing scaffolding to children and contributing to improved emergent literacy (Liao et al., 2020; Takacs et al., 2015). Moody et al. (2010) found that children showed higher levels of reading engagement with e-books than traditional books, and Segal-Drori et al. (2010) showed that children made greater progress in word reading and concept about print (CAP) with e-books than traditional books. E-books can overcome the limitations of traditional classroom reading provided the e-book is of high quality in facilitating learning. Consequently, the digital features found in the e-books should aim to produce gains in emergent literacy (Bus et al., 2009; de Jong & Bus, 2003; Korat & Shamir, 2008; Moody, 2010). Traditionally, e-books are meant to be used individually by the children on a computer. Unfortunately, this requires many computers and, in this form, they act primarily as an extra tool to boost lingering skills.

Whole-class lessons can be facilitated, and shared reading can be improved, by showing the storybook on a SMART board. SMART boards are interactive white boards that can raise pupils’ motivation and learning engagement (Shenton & Pagett, 2007). Projection of enlarged pictures and texts onto a SMART board provides unhindered vision to all children in the classroom and allows practice with a high-quality e-storybook e.g., by using PowerPoint to implement learning tools. Digital features designed to provide evidence-based instructional techniques to target specific emergent literacy skills are given by Moody (2010). Examples are: word pronunciation tools to assist students with phonological awareness and decoding text, tools for drawing attention to important aspects of the story to promote vocabulary and understanding the narrative and interactive practices to promote child engagement and thus sustain attention to reading. Additional examples to improve shared reading with a SMART board can be found in Gill & Islam (2011). They mention, enlargement with a magnifier or highlights of text elements with color or moving words to draw visual attention to print through which students can learn concepts of print, build sight word vocabulary, and enhance phonological skills.

A further advantage of showing e-storybooks on a SMART board is the possibility to combine the development of key precursors from conventional forms of reading and later reading success. These key determinants of emergent literacy skills are related to print knowledge (alphabet knowledge and concepts about print; moderate to strong predictors of all conventional literacy skills) and measures of oral language, specifically vocabulary and phonological awareness (both moderate predictors) (Lonigan et al., 2008). They are correlated during development, but differentially predictive of different aspects of later conventional literacy skills. The code-related skills facilitate children’s abilities to acquire the alphabetic principle successfully and are predictive of decoding text accurately and fluently. The meaning-related skills, primarily associated with language, allow children to comprehend text once it is decoded.

The above-mentioned domains also appear to be responsive to different types of instructional activities. Lonigan et al. (2013) combined meaning-focused (dialogic reading, shared reading) and code-focused (phonological awareness, letter knowledge) interventions and found that interventions had statistically significant positive impacts only on measures in the respective skill domains. Combinations of interventions did not enhance outcomes across domains, indicating instructional needs in all areas of weakness for young children at risk for later reading difficulties. Similarly, Justice et al. (2010) found that the positive effect of code focused interventions did not extend to children’s meaning focused skills. Also, Bowyer-Crane et al. (2008) reported that children who received a code focused intervention, outscored children who received a meaning-focused intervention on measures of letter knowledge and phonological awareness and vice versa on measures of vocabulary and grammar.

To enhance all emergent literacy skills, it would be efficient to expose children to a single intervention promoting the development of code related as well as meaning related skills. As mentioned above, Lonigan et al. (2013) did not find the expected synergistic effect of such a combination. The question remains whether adding skill training to an evidence-based intervention aimed at a different skill improvement, interferes with the approved intervention. In other words: Is a combination of skill training worthwhile without a loss of impact on the development of either skill? The human mind has a limited capacity for the simultaneous processing of information (Mayer, 2020; Sweller, 2005). Attention guiding to select relevant information from multimodal information can be an effective means of making efficient use of this limited capacity (Alpizar et al., 2020). However, this effect has been found for verbal or visual cues (signals) to either facilitate meaning focused or code focused learning (Arslan-Ari & Ari, 2021) not for switching back and forth in simultaneous learning of code and meaning related input. According to the working memory model (Baddeley, 2003), children have to switch between code and meaning related input. A useful integration of this wide-ranging nature of input will depend on the capacity of their working memory. Variability in other regulatory skills like cognitive flexibility and self-control will have similar effects (Diamond et al., 2007). Therefore, rather detrimental instead of synergistic effects of combining interventions are expected.

In this study, we report the results of 2 experiments. The main experiment focusses on the acquisition of print knowledge, phonological awareness and vocabulary, using the print referencing technique with e-book reading on a SMART board. We ask the question if a combination of training these skills simultaneously in an evidence-based intervention is worthwhile, i.e., without a loss of impact to improve either skill. A pilot experiment was conducted to disclose the impact on learning print from e-picture books by using print referencing and to fine-tune this technique. The influence of variation in regulatory skills will be the subject of future research.

Emergent literacy development using print referencing

As will be clear from the introduction, all concepts of emergent literacy promoting later reading success can be addressed using e-books. It has been demonstrated to be effective for story comprehension, expanding vocabulary and syntax and promoting phonological awareness (Korat, 2010; Korat et al., 2014; Shamir & Shlafer, 2011; Shamir et al., 2008, 2012; Smeets & Bus, 2012; Verhallen et al., 2006), as well as print knowledge (Gong & Levy, 2009; Moody et al., 2014; Shamir & Shlafer, 2011).

Expanding vocabulary by reading electronic books with only a reading mode has been shown in several studies (e.g., Evans & Saint-Aubin, 2013; Smeets & Bus, 2012; Verhallen et al., 2006). The illustrations are inspected in concert with the spoken text (Evans & Saint-Aubin, 2013). The children navigate the illustrations in an attempt to match what they see with what they hear, which helps the children to retain the story text (Verhallen & Bus, 2012) and enables them to add new low frequency words to their vocabulary (Evans & Saint-Aubin, 2013).

When reading storybooks, children spend more than 90% of the time on looking at the pictures (Evans & Saint-Aubin, 2013). As a result, less attention is paid to the print features: about 5–6% of the total reading time (Evans & Saint-Aubin, 2013; Evans et al., 2008; Justice et al., 2008). Lin et al. (2018) showed that children’s attention to words significantly predicted posttest word reading (Chinese two characters words). This suggests that in order to increase print knowledge in general, attention should be drawn to the printed elements of the book. The time spent on fixating printed matters can be significantly increased by pointing to the text (Evans et al., 2008) or using other forms of print referencing (Justice et al., 2008; Skibbe et al., 2018). Diverse forms of drawing children’s attention to print in shared book-reading sessions, have been shown to improve print awareness (Gettinger & Stoiber, 2014; Justice & Ezell, 2002) as well as in e-books with code-focused embedded tools (Gong & Levy, 2009; Shamir & Shlafer, 2011; Shamir et al., 2012).

Enhancement of phonological awareness will also benefit from drawing attention to print: animated e-books (Ihmeideh, 2014) and especially multimedia books with an embedded tool for dividing and sounding out words (Chera & Wood, 2003; Shamir & Shlafer, 2011) show improvement in phonological awareness kindergartners.

The present study

The present study examines the feasibility to enhance different domains of early literacy in one intervention: Is it possible to train print knowledge, vocabulary and phonological awareness during shared book reading with print referencing without a loss of impact in either skill learning?

It is expected that e-books with a print referencing tool shown on a SMART board to children in a classroom:

-

1.

Contribute to acquisition of print knowledge, growth of phonological awareness as well as to enrichment of vocabulary

-

2.

Increase vocabulary to a lesser extent than e-books with only a reading mode

This expectation is based on the limited capacity for simultaneous processing of information of the human mind (Sweller, 2005). The central executive of the working memory might be overloaded when switching back and forth between code and meaning related input when processing this information and the episodic buffer might not get enough information for successful integration of the visual and phonological input (Baddeley, 2003). The embedded tool of focusing attention to print during the shared book reading intervention, facilitates print and phonological skill learning, but divert attention from pictures and interrupts the storyline which might frustrate simultaneous and successful new word learning.

Method

Participants

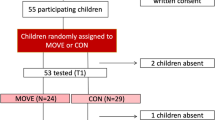

A total of 80 kindergarteners (40 boys and 40 girls) between 4 and 6 years old (M = 60.13 months, SD = 6.74) from 6 different classrooms groups participated in this study. They were typically developing children from mixed but generally middle-socioeconomic status (SES) families with Dutch as first language. Participating children’s mean standardized scores on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT, M = 75,49, SD = 12.87) indicated that the sample was somewhat above average in vocabulary.

Design

A pretest–posttest within subject design, the same participants in all conditions of the experiment, was used to examine the influence of storybook reading with print referencing on the development of print knowledge, phonological awareness and book specific vocabulary.

Each group of children heard 4 different storybooks in 2 different formats on the SMART board in the classroom: the first two stories (T1 and T2) were presented in a simple e-book format where a voice-over tells the story while the children look at the accompanying pictures with the written story text; the next 2 story books (PR1 and PR2) include, beside the (spoken and written) text, a print referencing tool (see below). The fifth storybook (CB) served as a control: book specific vocabulary was tested pre- and post-intervention without hearing the story. To diminish the influence of differential performance across storybooks, the books were counter-balanced for conditions and groups of children. All children were pre- and post-tested on Print Knowledge, Phonological Awareness and book specific (target) expressive Vocabulary. Target Vocabulary was also tested half way the intervention, i.e., after book 1 and 2 without the print referencing tool and half of the children (N = 43; Cohort 1) were half way tested on Print Knowledge and Phonological Awareness (i.e., after T1/T2 condition). To determine which children are administered this extra test, they were divided into 2 Cohorts (0 and 1), matched on their scores of the Print referencing pretest and general vocabulary (PPVT) (see Table 1 for the experimental set up and distribution of e-books on the different groups and conditions).

Materials

Storybooks

Five Dutch storybooks were available as electronic story books: Beer is op Vlinder [Bear is in Love with Butterfly] (van Haeringen, 2004), Rokko Krokodil [Rocco the Crocodile] (de Wijs & van den Hurk, 2001), Tim op de Tegels [Pete on the Pavement] (Veldkamp & de Boer, 2004), Na-Apers (Copycats) (Veldkamp & de Boer, 2006) and Kleine Kangoeroe [The Minute Marsupial] (van Genechten, 2005). Each story was available in 2 forms (simple e-book with Text and e-book with Print Referencing).

Print referencing tool

To focus attention of children on printed matters several print referencing features were built into a power point presentation of the e-book to address all concepts of print knowledge. Sentences were highlighted at the speed of the reading voice over, letters and words turned into a different color and were subsequently pronounced by the experimenter (e.g., ‘his is the letter B, the Bu from Bear), print conventions, like the usage of a comma or question mark, were pointed out and briefly explained and print violations of words (e.g. words containing only vowels or consonants) and sentences (e.g., all words connected together) were corrected by an animation while the experimenter commented with: oh, oh this word c.q. sentence is spelled incorrectly. In order to be able to watch the animations and listen to the comments of the experimenter, the story was interrupted for a short while.

To refer to the phonology of letters and words the highlighted letters in the print referencing e-books were sounded out loud in combination with the word they belong to (e.g., this is the Mmm from Mother) and the highlighted words were also sounded out loud by the assistant and either broken down into their phonemes and subsequently blended to the complete word (e.g., m-a-m-a, mama) or broken down into syllables while clapping hands for each part (e.g., wing-flapping wing-fla-pping).

Vocabulary tests

A Dutch version of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-III-NL, Schlichting, 2005) was used to assess children’s verbal intelligence (general receptive vocabulary).

A cued expressive vocabulary test was administered to assess children’s knowledge of words that were used in the target storybooks. Children were asked to complete sentences, which did not resemble the exact phrases in the storybooks, with target words. The experimenter read an incomplete sentence (e.g., ‘Rokko is sitting on a …..’), while corresponding pictures from the storybooks (e.g. Rokko sitting on a ‘jetty’ with a rowing boat attached to it) were shown on screen. Children’s responses were coded as correct when they completed the sentence with the target word. In creating this test, low frequency words as listed by Schrooten & Vermeer (1994) were selected assuming that they would be unknown by most kindergarten children. The test consisted of 35 target words (7 from each storybook). The words are found to be relatively unknown and revealed neither ceiling nor bottom effects in prior research (Smeets & Bus, 2012; Verhallen & Bus, 2012; Verhallen et al., 2006). The reliability of the test is high (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.85).

Code related skills test

Print knowledge was measured with a Concepts of Print Test (CPT) containing all key areas of print awareness (print concepts, concept of word and alphabetic knowledge), based on Justice & Ezell (2004), Zucker, Moody, et al. (2009), Zucker, Ward, et al. (2009)) and the print tests used by Clay (1989, 2000) and Gong & Levy (2009). The CPT consists of 8 items about print concept (e.g., ‘where do I start reading’), 7 items about the organization of text in sentences, words and letters (e.g., ‘Point to the first sentence/word/letter’), 6 items about alphabetic knowledge and 8 items about interpunction (e.g., ‘what is the name of this sign and where do you use it for’). The questions were asked by the experimenter, while the children looked at pictures from the story book, they had read that week. The CPT pre-test contains pictures from a storybook unknown to the children. The maximum score of this part of the test was 29. The last category was a discrimination task containing two classes, readable print and print violations, in 3 types of word concept: shape, elements and spelling (Gong & Levy, 2009). Each type was combined in 1 score (0 points for up to 3 successes (chance level), 1 point for 4 or 5 successes and 2 points for 6 successes), which make a maximum score of 30 for this category. The CPT post-tests were adapted for the alphabetic knowledge and pictures of each storybook. The reliability of the test is high (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.91).

Phonological skills test

Phonological awareness tasks were adjusted from 2 sub-test of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals, fourth edition, Dutch version (CELF-4-NL; Kort, et al., 2008): Phoneme Combination and Syllables Clapping. For both tasks the CELF test of 5 items was completed with 10 words taken from the picture books with two up to five phonemes and 6 syllables to combine (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.94).

Procedure

Experimental storybooks were shown on a SMART board and read to all children in their own classroom on 4 successive weeks. The first two weeks two e-picture books in the simple format with the written story text were alternately presented 3 times on different days and the last two weeks the two e-picture books in the Print Referencing version were alternately presented 3 times on different days (the order in which book titles are read is shown in Table 1). In the Print Referencing condition, it was the experimenter who made the referencing notes.

Testing took place in a spare room in the school. The experimenter tested the children of the experimental group individually. The tests were digitalized and shown on a laptop with a wide screen. All book-specific vocabulary (Voc), print knowledge (PK) and phonological awareness (PhA) tests were pre tested in the week before the intervention started and for Cohort 1 post tested on a successive day after each condition (T or PR) in the same week. For Cohort 0 PK and PA were not administered after the T-condition. The control-test for book-specific vocabulary was post tested after the last intervention. Tests to measure general receptive vocabulary (PPVT; a measure of verbal intelligence) and regulatory skills were administered during the 4 intervention weeks on days that story books were read in class. The test sessions lasted about 15 min each.

Analysis

Data are analysed using a Repeated Measure ANOVA (RMA). When conducting RMA, the accuracy of the F-test depends upon the assumption that behavior between different participants is independent and data are normally distributed. Also, the assumption of sphericity has to be made that the level of dependence between experimental conditions is roughly equal (Field, 2009). The behavior between the different participants is expected to be independent, because the intervention is completed by trained assistants and children’s responses to test items are individual. Moreover, the e-books are counterbalanced between classes and conditions. The assumption of normality is investigated using the Shapiro–Wilk test (N < 50) and Q-Q plots or the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (N > 50) (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Violation of normality will not cause major problems with larger sample sizes (N ≥ 30) (Gravetter & Wallnau, 2004). The assumption of sphericity is investigated using Mauchly’s test and violations are corrected with Huynh–Feldt estimates (Field, 2009).

Planned comparisons are conducted by using Helmert contrasts to reveal any difference between the conditions. To discover whether the effects of the intervention are substantive, partial η2 is given (ηp2 = 0.01 represents a small, ηp2 = 0.06 medium and ηp2 = 0.14 a large effect) and the F-values of the tests are converted into r-values. An effect size r > 0.5 constitutes a very large effect and accounts for 25% of the variance, r = 0.30 represents a medium effect and accounts for 9% of the total variance and r = 0.10 is a small effect, it explains 1% of the total variance (Field, 2009).

Pilot experiment

A pilot experiments was conducted to fine tune the Print referencing tool and to rule out print learning from being tested as much as possible.

Method

Within subject design with 32 kindergartners (27 with a complete dataset for print knowledge) between 4.5 and 6 years old (M = 64 months, SD = 3). The intervention consisted of 4 different storybooks, counterbalanced for the children and for conditions shown in the classrooms on a smartboard. Three conditions were tested in a fixed order: (a) storybook with spoken text; (b) storybook with spoken and written text; (c) storybook with spoken and written text and a print referencing tool. The storybooks were presented 3 times on different days.

The materials, tests and data analysis were the same as in the main study except that phonological awareness training and testing was not incorporated in this study.

Results

We conducted a Repeated Measures ANOVA (RMA) on print knowledge (PK) using Time (pre vs. post) and Condition (No Text (NT), With Text (WT), Print Referencing (PR)) as within-subjects factor. The Shapiro–Wilk tests for pre- and post-test PK variables are not significant and all the points of the normal Q-Q plots are on or near the strait line. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity has not been violated for the main effects of time and condition (p < 0.616). All effects are reported as significant at p < 0.05.

There was a significant main effect of Time F(1, 27) = 41.94, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.608, the mean values revealed that ratings of post-tests were significantly higher than pre-tests, and a significant main effect of Condition F(2, 54) = 7.76, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.223. There was a significant interaction effect between Time and Condition, F(2, 54) = 10.58, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.281. This indicates that growth of print knowledge was not the same in the three conditions. A priori contrasts were performed comparing Time and Conditions to their baselines (pre–test and No-Text). These revealed significant interactions when comparing NT to PR, F(1, 27) = 17.09, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.339, r = 0.63 and WT to PR F(1, 27) = 13.33, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.331, r = 0.51. Looking at the interaction graph (Fig. 1a), it shows that the gain in print knowledge in the No Text condition equals the gain in the Text condition and that Print Referencing compared to these two conditions increased performance significantly. These contrasts yield large effect sizes. Viewing the gain in print knowledge over time (Fig. 1b) shows growth after the No-text condition (black line), no progress after the Text condition (light grey line) and again an increase in print knowledge after the print referencing condition (dark grey line). This indicates that children gain some print knowledge from being tested (test effect). The presents of text without referring to it, does not add to print knowledge (Fig. 1b, time 2 to 3), but focussing attention to print does increase print knowledge (Fig. 1b, time 3 to 4).

Main experiment

Print Knowledge

We conducted an RMA with a priory contrast on print knowledge using Condition (Pre-test (Pt), Text (T), Print Referencing (PR)) as within-subjects factor. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests for pre- and post-test PK variables are not significant and all the points of the normal Q-Q plots are on or near the strait line. For Cohort 1 Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity has not been violated (p < 0.949). There was a significant main effect of Condition F(2, 84) = 32.42, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.436, r = 0.53. The contrasts revealed that ratings after T were significantly higher than after Pt, F(1, 42) = 9.45, p < 0.004, ηp2 = 0.184, r = 0.43 as well as ratings after PR were significantly higher than after T, F(1, 42) = 25.14, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.374, r = 0.61 with a very high effect size (Table 2a).

RMA for Cohort 0 revealed a significant main effect of Time (Pre-test (Pt) and post-test Print Referencing (PR)) F(1, 36) = 32.48, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.474, r = 0.69 with a very high effect size. This indicates that in Cohort 1 print knowledge increases from being tested after the Text condition (Fig. 2a cohort 1) and increases from print referencing after the PR condition. This gain in print knowledge after PR is not the result from being tested twice, because test-effects were only found once in the pilot experiment (after the NT condition (Fig. 1b, time 1 to 2) and not after the WT condition (Fig. 1b, time 2 to 3)).

Print knowledge of interpunction (PKI) is hard to learn from a test (e.g., asking the name and meaning of a sign, while showing a question mark), but will be learned from print referencing. An RMA for Cohort 1 is conducted on PKI. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity has been violated for the main effect of Time (p < 0.002), therefore degrees of freedom were corrected using Huynh–Feldt estimates of sphericity (ε = 0.816). The results confirm the expectation: the model for PKI cohort 1 is significant, F(1.6, 34.8) = 31.41, p < 0.001 and repeated contrasts revealed that ratings after the post-test condition T equals ratings after the pre-test condition T, F(1,42) = 0.026, but were significantly higher after PR, F(1,42) = 39.31, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.483, r = 0.70 with high effect size (Table 2, Fig. 2b).

Phonological awareness

We conducted an RMA with a repeated contrast on phonological awareness using Condition (Pre-test (Pt), Text (T), Print Referencing (PR)) as within-subjects factor for cohort 1. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests for pre- and post-test PK variables are not significant and all the points of the normal Q-Q plots are on or near the strait line. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity has not been violated (p < 0.962). There was a significant main effect of Condition F(2, 84) = 32.42, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.314. The contrasts revealed that ratings after T were as high as after Pt, F(1, 42) = 0.019, p < 0.89, but ratings after PR were significantly higher than after T, F(1, 42) = 24.82, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.371, r = 0.61 with a very high effect size (Table 2). The RMA conducted on all participants revealed that ratings after PR were significantly higher than after Pt, F(1, 80) = 46,41, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.370, r = 0.61 with a very high effect size (Table 2, Fig. 3).

The analysis show that phonological awareness does not increase from being tested nor from books being read to them without referring to print, but that books being read in a print referencing style contribute to phonological skills.

Vocabulary

We also conducted an RMA on target vocabulary using Time (pre- vs. post-test) and Condition (Control book (C), Text (T), and Print Referencing (PR)) as within-subjects factor. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests for post-test vocabulary variables are not significant and all the points of the normal Q-Q plots are on or near the strait line; for pre-tests and post-test Control condition, variables are significant (p > 0.001) and the Q-Q plots show outliers at the end of the strait line. This deviation of normality was expected as a result of testing unknown words and will not affect the results because the sample size is large. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity has not been violated for the main effects of time and condition. All effects are reported as significant at p < 0.05.

There was a significant main effect of Time F(1, 79) = 170.0, p < 0.0001, ηp2 = 0.683, and a significant main effect of Condition F(2, 158) = 24.38, p < 0.0001, ηp2 = 0.236. There was a significant interaction effect between Time and Condition F(2, 158) = 51.27, p < 0.001, partial ηp2 = 0.394. Helmert contrasts revealed that ratings after T and PR were significantly higher than after the control condition, F(1, 79) = 95.09, p < 0.001, partial ηp2 = 0.546, r = 0.74 with a large effect size. Conversely there was no significant difference between T and PR, F(1, 79) = 2.62, p < 0.1, ηp2 = 0.032, r = 0.18 (Table 2, Fig. 4). This indicates that children learn words from books being read to them and that a print referencing style increase vocabulary to the same extent as e-books with only a reading mode.

For as well print learning as phonological and vocabulary growth, the between-subject effects were significant: for print learning cohort 1 F(1,42) = 218.40, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.839 and for cohort 0, F(1,36) = 209.63, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.853; for phonological awareness, F(1, 79) = 251,0, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.761 and word learning F(1, 79) = 658.38, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.794. Children differ to a large extent in development of these skills even though they are in the same class or age range. Differences in regulatory skills between the kindergartners are a good candidate to explain some variances in learning gains and will be addressed in future research.

Conclusion

E-picture-books with a print referencing tool that focus children’s attention on a classroom SMART board stimulates the acquisition of print knowledge, growth of phonological awareness and enriches vocabulary at the same time.

The Pilot experiment indicates that children gain some print knowledge from being tested. However, reading a picture book without referring to the story text in the book, does not add to print knowledge, while focussing attention to print will increases print knowledge (Fig. 1a). Therefore, it can be concluded from the main experiment that in cohort 1 print knowledge increases from being tested after the Text condition (T) and increases from print referencing after the Print referencing condition (PR; Fig. 2a). Consequently, focussing attention to print will increases print knowledge and is not the result of being tested twice, because test-effects were only found once in the pilot experiment: after the No-Text condition (Fig. 1b, time 1 to 2) and not after the Text condition (Fig. 1b, time 2 to 3). This conclusion is enhanced by increasing punctuation knowledge in the main experiment where ratings after condition T were the same as pre-test valuations, but significantly higher after condition PR with a high effect size (Table 1).

The print referencing tool was also utilized to stimulate phonological awareness. Phonological skills do not develop from being tested nor increase from books being read to children without referring to print, but books being read in a print referencing style do contribute to phonological abilities. This growth in phonological awareness does not constrain simultaneous growth in print knowledge: the pilot experiment and the main experiment were accomplished with comparable populations and a similar print referencing test and raised print knowledge to the same extent.

Furthermore, the study revealed that vocabulary while reading e-books using a print referencing style improves to the same extent as in e-books with only a reading mode, thereby violating the second hypothesis.

Discussion

Storybook reading is an informative experience in developing early literacy. The meaning of a new word and, to a lesser extent, its phonological aspects, are picked up without specifically drawing attention to it (e.g., Robbins & Ehri, 1994; Sénéchal, 1997; Verhallen et al., 2006).

During reading children mainly focus on the illustrations in a book and pay less attention to the written text. Repeated reading of the same book increases the focus on text with just a few percent (Evans & Saint Aubin, 2013). The effect of storybook reading on print knowledge is therefore small and explicitly focusing attention towards print by means of an evidence-based method like print referencing seems important (Justice & Ezell, 2004; Skibbe et al., 2018). Also, development of phonemic awareness could benefit using a print referencing reading style (Justice & Ezell, 2004; Shamir et al., 2012). Storybook reading using a print referencing style could therefore be useful to develop all essential emergent literacy skills.

In the main study print knowledge increases after the reading intervention using print referencing, but also after the Text condition. This is contrary to what is found in the literature: a form of attention to print is necessary in order to gain print knowledge when a book is read to kindergartners. Since it is not plausible that children gain print knowledge by interacting with their environment in 2 weeks’ time in which no explicit learning of print knowledge took place, it makes us believe that the children picked up some knowledge from the print knowledge pretest. It is hard to design a test which does not have a suggestive effect e.g., when you ask a child: ‘how many words do you see?’ it is likely that it will count the only obvious entities on the page without knowing what a word is and learn the concept ‘word’ just from the focus on the text of the test. A comparison between cohort 0 (tested 2 times) and cohort 1 (tested 3 times) after the print referencing condition leads to the conclusion that this test learning has its limits: there was no significant difference in print knowledge between the 2 groups, which establish print learning from the print referencing intervention. This conclusion is strengthened by de results of the pilot study: print knowledge increased after reading the story books containing only pictures, which is even more unlikely than gaining print knowledge when text is present, but did not further increase after reading picture books also holding text. As stated before, there is only one week between each test, so children do not gain print knowledge by interacting with their environment. Therefore, it is more likely that learning took place from being tested. The need of attention to print is acknowledged by the expansion of interpunction understanding, a specific category of print knowledge. Knowledge of punctuation is needed to read a text with intonation (Torgesen & Hudson, 2006; van de Mortel, 2012) and essential to reading comprehension (Hudson et al., 2000). This kind of knowledge is hard to pick up from just reading a book nor from being tested, one doesn’t have to use giveaway questions regarding e.g., an exclamation mark or comma. The results indeed show no progress in punctuation understanding after the Text condition, but it developed after explaining punctuation by means of print referencing.

Additionally, phonological awareness increased after books read with print referencing, but not after the traditional reading. In order to become good readers, children have to develop phonological skills (Joseph & McCachran, 2003). Weak phonological awareness predicts reading problems (Phillips et al., 2008), but for children with well-developed phonological skills the reading process improves faster and vice versa, through reading their phonological skills are stimulated (Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998). Variance in exposure to spoken language before children enter school, leads to differences in the development of phonological skills (Antony & Francis, 2005). Training these skills will lead to a better reading process (Cunningham, 1990). Our results show that an easy way to stimulate this process is to draw attention to sound structures in words by means of print referencing. In this way print knowledge and phonological awareness can be stimulated together. These results tie in with previous research findings that kindergartners acquire more print knowledge (Gong & Levy, 2009; Justice & Ezel, 2004; Shamir & Shlafer, 2011; Evans et al., 2008; Moody et al., 2014), can read more words (Lin et al. (2018) and are more aware of word phonics (Justice & Ezell, 2004; Shamir et al., 2012) when books are read in a print focussing style compared to traditional reading.

Different domains of emergent literacy development appear to be receptive to different types of instructional activities (Lonigan et al., 2013). In the current study the evidence-based code-focused intervention, print referencing (Gong & Levy, 2009; Justice & Ezell, 2002; Shamir et al., 2012), was used to enhance print knowledge together with phonological awareness. The effectiveness of this method was investigated on vocabulary learning. There is ample evidence that expanding vocabulary through reading storybooks, a meaning-focused intervention, is effective (e.g., Evans & Saint-Aubin, 2013; Smeets & Bus, 2012; Verhallen et al., 2006). The illustrations are inspected in concert with the spoken text. The children navigate the illustrations in an attempt to match what they saw with what they heard, which enabled the children to add new low frequency words to their vocabulary (Evans & Saint-Aubin, 2013; Verhallen & Bus, 2012). The main problem addressed in the current study is the possible interference of print referencing, added to the meaning focused intervention to enhance vocabulary. This possibility of interference was based on the recognition of limited capacity of the human working memory (Badeley, 2003) and children having to switch back and forth between code and meaning related input during the shared reading sessions. Our results indicate that using a print referencing style during book reading, that briefly interrupts the narrative, enhances print knowledge and phonological awareness and is not detrimental to new word learning; although not significant, even more new words were learned in the print referencing condition compared to the Text condition which needs further attention. As well print knowledge and phonological awareness as word learning improved with a substantive effect when showing e-story books with print referencing on a Smart board in the classroom. To our knowledge this result is the first evidence that different domains of emergent literacy development can be addressed in one type of instructional activity for normally developing kindergarteners.

The study focused on the short-term benefits of two very important domains in early literacy using print referencing. Despite the short intervention children benefit in both domains with very high effect sizes. Justice et al. (2009) investigated print knowledge development through classroom-based teacher–child storybook reading with explicit print referencing and found a medium effect size (d = 0.5) after 120 reading sessions. Shamir et al. (2012) contrasted adult reading and individual e-book reading and found after 6 sessions an increase in a simple CAP score with a high effect (d = 0.7) for both interventions. In this light, print referencing, including a tool promoting the development of phonological awareness, while showing e-storybooks on a SMART board in the classroom, seems a very promising intervention to enhance all key areas of print awareness (print concepts, concept of word, alphabetic knowledge) and phonological awareness as well as vocabulary at the same time. Moreover, because the tool is built into the storybooks it overcomes the problem that teachers do not naturally use print referencing style while reading with children.

In future studies we will evaluate if this combination of skill training is worthwhile, for all children normally lacking behind in a classroom environment. This includes children with relatively low skills of executive functioning in general, especially those with problematic learning behaviour, often characterized by a short attention span. To hold attention of young children, it is important to vary instructions, use verbal end non-verbal references to print and interact actively (Zucker, Moody, et al., 2009; Zucker, Ward, et al., 2009). Especially the last recommendation is useful to individualize learning in a classroom setting.

It should be noted that the number of participants in the study is rather small, however a repeated measure design is statistical powerful. When the same participants are used across conditions the error variance is reduced, making it easier to detect any systematic variance (Field, 2009). Detailed recommendations for children entering school with a limited vocabulary requires a repetition of the experiment in schools with a high percentage of immigrant children and/or from families with low educational levels.

The results of this study indicate that reading e-picture books while using a print referencing tool is a good candidate to use as an integrated whole-classroom method to promote the essential early literacy skills to all children in the same school year. The possibility to interact with children offers the opportunity to differentiate in learning events and makes print referencing an efficient learning tool for a tailor-made educational setting and a contribution to lessen workload for teachers.

Data availability

Not applicable, data are stored and available agreeing the ethic approval; We are not allowed to share the data to protect the identity of the participants and to follow the requirement of the Research Committee – Panel on Research Ethics.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Alpizar, D., Adesope, O. O., & Wong, R. M. (2020). A meta-analysis of signaling principle in multimedia learning environments. Educational Technology Research & Development, 68(5), 2095–2119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09748-7

Antony, J. L., & Francis, D. J. (2005). Development of phonological awareness. American Psychological Society, 14(5), 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00376.x

Arslan-Ari, I., & Ari, F. (2021). The effect of visual cues in e-books on pre-K children’s visual attention, word recognition, and comprehension: An eye tracking study. Journal of Research on Technology in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1938763

Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory and language: An overview. Journal of Communication Disorders, 36, 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9924(03)00019-4

Bowyer-Crane, C., Snowling, M. J., Duff, F. J., Fieldsend, E., Carrol, J. M., Miles, J., et al. (2008). Improving early language and literacy skills: Differential effects of an oral language versus a phonology with reading intervention. Journal of Child. Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 422–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01849.x

Burchinal, M. R., Peisner-Feinberg, E. S., Pianta, R., & Howes, C. (2002). Development of academic skills from preschool through second grade: Family and classroom predictors of developmental trajectories. Journal of School Psychology, 40(5), 415–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(02)00107-3

Bus, A. G., Verhallen, M. J. A. J., & de Jong, M. T. (2009). How On screen Storybooks contribute to Early Literacy. In A. G. Bus & A. S. B. Neuman (Eds.), Multimedia and Literacy Development – Improving Achievement for Young Learners (pp. 153–167). Routledge.

Chera, P., & Wood, C. (2003). Animated multimedia ‘talking books’ can promote phonological awareness in children beginning to read. Learning and Instruction, 13, 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2006.00183.x

Clay, M. M. (1989). Concepts about print in English and other languages. The Reading Teacher, 42, 268–276.

Clay, M. M. (2000). Concepts about print: What have children learned about the way we print language? Heinemann Educational Books.

Cunningham, A. E. (1990). Explicit versus implicit instruction in phonemic awareness. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 50(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0965(90)90079-N

De Jong, M. T., & Bus, A. G. (2003). How well suited are electronic books to supporting literacy? Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 3, 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687984030032002

De Jong, M. T., & Bus, A. G. (2004). The efficacy of electronic books in fostering kindergarten children’s emergent story understanding. Reading Research Quarterly, 39(4), 378–393. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.39.4.2

De Wijs, I., & van den Hurk, N. (2001). Rokko Krokodil [Rocco the Crocodile]. Rotterdam: Ziederis.

Diamond, A., Barnett, W. S., Thomas, J., & Munro, S. (2007). Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science, 318, 1387–1388. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1151148

Evans, M. A., & Saint-Aubin, J. (2013). Vocabulary acquisition without adult explanations in repeated shared book reading: An eye movement study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105, 596–608. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032465

Evans, M. A., Williamson, K., & Pursoo, T. (2008). Preschoolers’attention to print during shared book reading. Scientific Studies of Reading, 12, 106–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888430701773884

Field, A. (2009). Discovering Statistics using SPSS. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Gettinger, M., & Stoiber, K. C. (2014). Increasing opportunities to respond to print during storybook reading: Effects of evocative print-referencing techniques. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29, 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.03.001

Gill, S. R., & Islam, C. (2011). Shared Reading goes High-Tech. The Reading Teacher, 66, 224–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.01028

Gong, Z., & Levy, B. A. (2009). Four-year-old children’s acquisition of print knowledge during electronic storybook reading. Reading & Writing, 22, 889–905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-008-9130-1

Gravetter, F. J., & Wallnau, L. B. (2004). Statistics for the behavioral sciences. Cengage Learning.

Ihmeideh, F. M. (2014). The effect of electronic books on enhancing emergent literacy skills of pre-school children. Computers and Education, 79, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.07.008

Inoue, T., Georgiou, G. K., Rauno Parrila, R., Kirby, J. R., & J.R. (2018). Examining an extended home literacy model: The mediating roles of emergent literacy skills and reading fluency. Scientific Studies of Reading, 22, 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2018.1435663

Joseph, L. M., & McCachran, M. (2003). Comparison of a word study phonics technique between students with moderate to mild mental retardation and struggling readers without disabilities. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 38(2), 192–199.

Justice, L. M., & Ezell, H. K. (2002). Use of storybook reading to increase print awareness in at- risk children. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2002/003)

Justice, L. M., & Ezell, H. K. (2004). Print referencing: An emergent literacy enhancement strategy and its clinical application. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 35, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2004/018)

Justice, L. M., Kaderavek, J., Fan, X., Sofka, A., & Hunt, A. (2009). Accelerating preschoolers’ early literacy development through classroom-based teacher– child storybook reading and explicit print referencing. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 40, 67–85.

Justice, L. M., McGinty, A. S., Piasta, S. B., Kaderavek, J. N., & Fan, X. (2010). Printfocused read-alouds in preschool classrooms: Intervention effectiveness and moderators of child outcomes. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41(4), 504–520. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2010/09-0056)

Justice, L. M., Pullen, P. C., & Pence, K. (2008). Influence of verbal and nonverbal references to print on preschoolers visual attention to print during storybook reading. Developmental Psychology, 44, 855–866. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.855

Korat, O. (2010). Reading electronic books as a support for vocabulary, story comprehension and word reading in kindergarten and first grade. Computers & Education, 55, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.11.014

Korat, O., & Shamir, A. (2004). Do Hebrew electronic books differ from Dutch electronic books? A replication of a Dutch content analysis. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 20, 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2004.00078.x

Korat, O., & Shamir, A. (2008). The educational electronic book as a tool for supporting children’s emergent literacy in low versus middle SES groups. Computers & Education, 50(1), 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2006.04.002

Korat, O., Shamir, A., & Segal-Drori, O. (2014). E-books as a support for young children’s language and literacy: The case of Hebrew speaking children. Early Child Development and Care, 184(7), 998–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2013.833195

Kort, W., Schittekatte, M., & Compaan, E. (2008). CELF-4-NL: Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals 4 Dutch-version. Pearson assessment and information B.V.

Liao, C.-N., Chang, K.-E., Huang, Y.-C., & Sung, Y.-T. (2020). Electronic storybook design, kindergartners’ visual attention, and print awareness: An eye-tracking investigation. Computers & Education. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103703

Lin, D., Chen, G., Liu, Y., Liu, J., Pan, J., & Mo, L. (2018). Tracking the eye movement of four years old children learning Chinese words. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 47(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-017-9515-x

Lonigan, C. J., Purpura, D. J., Wilson, S. B., Walker, P. M., & Clancy-Menchetti, J. (2013). Evaluating the components of an emergent literacy intervention for preschool children at risk for reading difficulties. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 114, 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2012.08.010

Lonigan, C. J., Schatschneider, C., & Westberg, L. (2008). Identification of children’s skills & abilities linked to later outcomes in reading, writing, and spelling. Developing early literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel (pp. 55–106). National Institute for Literacy.

López-Escribano, C., Valverde-Montesino, S., & García-Ortega, V. (2021). The impact of e-book reading on young children’s emergent literacy skills: An analytical review. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 18(12), 6510.

Mayer, R. (2020). Multimedia learning (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Mol, S. E., Bus, A. G., & de Jong, M. T. (2009). Interactive book reading in early education: A tool to stimulate print knowledge as well as oral language. Review of Educational Research, 79(2), 979–1007. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021890

Moody, A. K. (2010). Using electronic books in the classroom to enhance emergent literacy skills in young children. Journal of Literacy and Technology, 11(4), 22–44.

Moody, A. K., Justice, L. M., & Cabell, S. Q. (2010). Electronic versus traditional storybooks: Relative influence on preschool children’s engagement and communication. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 10, 294–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798410372162

Moody, A. M., Skibbe, L. E., Parker, M. P., & Walker, A. (2014). Use of electronic storybooks to promote print awareness in preschoolers who are living in poverty. Journal of Literacy and Technology, 15, 2–27.

Mortel, K. van de (2012). Lezen zoals je praat. Amersfoort: CPS. https://www.cps.nl/l/library/download/urn:uuid:cf135947-ee81-41b9-b2a5-9c9051e72fcc/

Phillips, B. M., Clancy-Menchetti, J., & Lonigan, C. J. (2008). Successful phonological awareness instruction with preschool children: Lessons from the classroom. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 1, 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121407313813

Robbins, C., & Ehri, L. C. (1994). Reading storybooks to kindergartners helps them learn new vocabulary words. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86, 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.86.1.54

Savva, M., Higgins, S. E., & Beckmann, N. (2021). Meta-analysis examining the effects of electronic storybooks on language and literacy outcomes for children in grades Pre-K to grade 2. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38, 525–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12623

Schlichting, L. (2005). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III-NL. Harcourt Test Publishers.

Schrooten, W., & Vermeer, A. (1994). Woorden in het basisonderwijs: 15.000 woorden aangeboden aan leerlingen [Words in primary schools: 15.000 words offered to pupils]. Tilburg: University Press.

Segal-Drori, O., Korat, O., Shamir, A., & Klein, P. (2010). Reading electronic and printed books with and without adult instruction: Effects on emergent reading. Reading and Writing., 23, 913–930.

Sénéchal, M. (1997). The differential effect of storybook reading on preschoolers’ acquisition of expressive and receptive vocabulary. Journal of Child Language, 24, 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000996003005

Shamir, A., Korat, O., & Barbi, N. (2008). The effects of CD-ROM storybook reading on low SES kindergartners’ emergent literacy as a function of learning context. Computers and Education, 51, 354–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.05.010

Shamir, A., Korat, O., & Fellah, R. (2012). Promoting vocabulary, phonological awareness and concept about print among children at risk for learning disability: Can e-books help? Reading and Writing, 25, 45–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-010-9247-x

Shamir, A., & Shlafer, I. (2011). E-books effectiveness in promoting phonological awareness and concept about print: A comparison between children at risk for learning disabilities and typically developing kindergarteners. Computers & Education, 57, 1989–1997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.05.001

Shenton, A., & Pagett, L. (2007). From ‘bored’ to screen: The use of the interactive whiteboard for literacy in six primary classrooms in England. Literacy, 41(3), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9345.2007.00475.x

Skibbe, L. E., Thompson, J. L., & Plavnick, J. B. (2018). Preschoolers’ visual attention during electronic storybook reading as related to different types of textual supports. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46(4), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-017-0876-4

Smeets, D. J. H., & Bus, A. G. (2012). Interactive electronic storybooks for kindergartners to promote vocabulary growth. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 112, 36–55.

Smith, G. G. (2012). Computer game play as imaginary stage for reading: Implicit spatial effects of computer games embedded in hard copy books. Journal of Research in Reading, 35, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2010.01447.x

Sweller, J. (2005). Implications of cognitive load theory for multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 19–30). Cambridge University.

Tabachnic, B., & Fidell, L.S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th edn.). Pearson Education, Inc./Allyn and Bacon.

Takacs, Z. K., Swart, E. K., & Bus, A. G. (2015). Benefits and pitfalls of multimedia and interactive features in technology-enhanced storybooks. Review of Educational Research, 85(4), 698–739. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654314566989

Torgesen, J. K., & Hudson, R. F. (2006). Reading fluency: Critical issues for struggling readers. What research has to say about fluency instruction (pp. 130–158). Newark: International Reading Association.

Van Genechten, G. (2005). Kleine Kangoeroe [The Minute Marsupial]. Hasselt: Clavis.

Van Haeringen, A. (2004). Beer is op Vlinder [Bear is in Love with Butterfly]. Leopold.

Veldkamp, T., & de Boer, K. (2004). Tim op de Tegels [Pete on the Pavement]. Van Goor.

Veldkamp, T., & de Boer, K. (2006). Na-apers [Copycats]. Lannoo.

Verhallen, M. J. A. J., & Bus, A. G. (2012, July). Beneficial effects of illustrations in picture storybooks for storing and retaining story text. In M.T. de Jong (Chair), Young children’s visual attention to illustrations and print as a source for learning. Symposium conducted at the Society for the Scientific Study of reading. Montreal, Canada.

Verhallen, M. J. A. J., Bus, A. G., & de Jong, M. T. (2006). The promise of multimedia stories for kindergarten children at risk. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(2), 410–419. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.2.410

Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69(3), 848–872. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06247.x

Zucker, T. A., Cabell, S. Q., Justice, L. M., Pentimonti, J. M., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2013). The role of frequent, interactive prekindergarten shared reading in the longitudinal development of language and literacy skills. Developmental Psychology, 49(8), 1425–1439.

Zucker, T., Moody, A., & McKenna, M. (2009). The effects of electronic books on pre- kindergarten-to-grade 5 students’ literacy and language outcomes: A research synthesis. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 40, 47–87. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.40.1.c

Zucker, T. A., Ward, A. E., & Justice, L. M. (2009). Print referencing during read-alouds: A technique for increasing emergent readers print knowledge. Reading Teacher. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.63.1.6

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

ECPW-2016/149, Leiden University; attached (in Dutch).

Informed consent

Included in ethic approval.

Consent for publication

Included in ethic approval.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

van Dijken, M.J. Print referencing during e-storybook reading on a SMART board for kindergartners to promote early literacy skills. Read Writ 36, 97–117 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10304-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10304-3