Abstract

Early failure to learn writing skills might go unnoticed and unremedied unless teachers adopt specific strategies for identifying and supporting students who learn at a slower pace. We implemented a Response to Intervention (RTI) program for teaching narrative writing. Over 18 months from start of primary school, 161 Spanish children received instruction in strategies for planning text and training in handwriting and spelling, and completed very regular narrative writing tasks. Data from these tasks were analysed to identify students at risk of falling behind. These students then completed additional, parent-supervised training tasks. During this training the quality of these students’ texts improved more rapidly than those of their peers. The resulting decrease in difference relative to peers, as measured by both regular narrative tasks and by post and follow-up measures, was sustained after additional training ceased. Interviews and questionnaires found good parent and teacher buy-in, with some caveats. Findings therefore indicate the feasibility and potential value of a RTI approach to teaching writing in single-teacher, full-range, first-grade classes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Learning to compose good text requires a range of skills. According to the simple view of writing (Juel et al., 1986), writers need both transcription (handwriting and spelling) and ideation skills. Transcription skills, plus syntax knowledge, are necessary to transform linguistic representations into written sentences. Ideation, in turn, involves generating and structuring relevant content. The later, not-so-simple view of writing (Berninger & Winn, 2006) argued that writers also need self-regulation strategies. This followed cognitive theory (Flower & Hayes, 1981) and instructional practice (Harris & Graham, 1996) that emphasised the importance of deliberate, executive control over ideation processes. Consistent with these previous accounts, Kim and Park (2019, Direct and Indirect Effects Model) argued that written composition ability depends both on transcription ability (spelling accuracy and handwriting fluency) and on discourse knowledge. Discourse knowledge here refers to the ability to orally retell a narrative (Kim & Schatschneider, 2017). Discourse knowledge is in turn predicted by the extent of a child’s vocabulary and syntax knowledge and of their higher-level thinking-and-reasoning skills (inference, perspective taking). Both this account and the not-so-simple view of writing argue that domain-general attentional and working memory abilities act as a fundamental constraint on written composition performance.

Early writing instruction typically focuses largely on transcription (Cano & Cano, 2012; Cutler & Graham, 2008; Dockrell et al., 2016). This makes sense given that in elementary grades, as might be expected, transcription ability predicts writing performance (Dunsmuir & Blatchford, 2004; Jiménez & Hernández-Cabrera, 2019; Kim, 2020; Kim & Park, 2019; Kim & Schatschneider, 2017; Limpo & Alves, 2013a). There is evidence that teaching spelling (Graham & Santangelo, 2014) and handwriting (Santangelo & Graham, 2016) benefits not just transcription skills, but also the compositional quality of young writers’ texts. Alongside transcription, students need to learn to construct complex sentences (Berninger et al., 2011; Saddler et al., 2018). Evidence suggests the benefits of teaching sentence-combining in upper-elementary grades (Limpo & Alves, 2013b; Saddler et al., 2008), though its effects in early grades remain unknown.

Teaching lower-primary students strategies for generating and structuring ideas is, however, less common (Bingham et al., 2017; Dockrell et al., 2016). Reasons might be related to the risk of cognitive overload (McCutchen, 1996; Torrance & Galbraith, 2006) or the little spare capacity young children devote to higher-level processing (Fayol, 1999). Learning about text structure, however, adds communicative purpose to the act of writing, which is potentially motivating (Teberosky & Sepúlveda, 2009). Additionally, learning self-regulatory strategies for planning and structuring content may reduce the tendency for cognitive overload (Kellogg, 1990) and reliance on external prompts. There is some evidence that teaching planning strategies in first grade benefits compositional quality (Arrimada et al., 2019; Zumbrunn & Bruning, 2013). These studies rely on strategy-focused instruction, an instructional approach aimed at teaching self-regulating planning and/or revising strategies so that students eventually use them independently (Fidalgo & Torrance, 2018; Harris & Graham, 2018). This approach tends to outperform other instructional practices in writing (see meta-analyses by Graham & Harris, 2018; Koster et al., 2015).

Theory and evidence suggest, therefore, that instruction in transcription, sentence construction and planning potentially benefits students’ texts from the start of formal writing instruction. A major concern with this approach, however, is that it can leave some students behind. Rijlaarsdam et al. (2000, 2011) point to the double challenge faced by developing writers as they learn new skills whilst simultaneously grappling with the demands of forming sentences (Rijlaarsdam & Couzijn, 2000; Rijlaarsdam et al., 2011). This is likely to be the case for first-grade students. Arrimada et al. (2019) found that, although strategy-focused instruction raised the mean performance substantially, 23% students did not respond positively to intervention between pre and posttest, and 35% between pre and delayed posttest. An effective first-grade curriculum that teaches composition skills needs to identify and support this minority.

The Response to Intervention (RTI) model is “a systematic and data-based method for identifying, defining and resolving students’ academic and/or behavioural difficulties” (Brown-Chidsey & Steege, 2005, p. 2). RTI aims to prevent learning disabilities through early identification of students who are slow to learn within a specific domain and by providing them with increasingly intense support. If all students are provided with robust, evidence-based instruction, those children whose rate of learning falls substantially below that of their peers will be at risk of more permanent deficit. These students need additional, remedial intervention to bring their rate of learning back within typical range. RTI replaces static diagnostic tests with continuous progress monitoring, aimed at identifying and supporting students who are falling behind.

RTI-based instructional programs have several key components: (a) Universal screening to identify students from whom non-responders are likely to emerge; (b) standardised instruction for all students, using methods previously found effective, so that slower learning can be attributed to the child’s response to instruction; (c) ongoing monitoring of students’ progress; and (d) additional intervention for students who fail to learn. These principles are worked out in three tiers of instruction (Barnes & Harlacher, 2008). All students receive Tier 1 instruction. Progress monitoring permits early identification of students who are learning slower than their cohort. These students are given additional Tier 2 instruction that runs concurrently with Tier 1 and aims to bring students’ rate of learning back within normal range. Students who fail to develop under Tier 2 are eligible for intensive, individualised, intervention. Implementation of this last tier (Tier 3) is, however, beyond the scope of this study.

To date, RTI approaches to instruction have focussed almost exclusively on reading and mathematics. Within these domains, they have been widely adopted, particularly in English-speaking countries (Berkeley et al., 2009), and there is evidence that they are successful in reducing the percentage of students requiring special education (see meta-analysis by Burns et al., 2005). Hattie (2012, 2015) estimated a standardised effect size of 1.07 for the RTI approach. Teachers’ attitudes towards RTI also tend to be positive. They find it valuable in supporting students’ learning (Greenfield et al., 2010; Rinaldi et al., 2011; Stuart et al., 2011) and believe it has a positive impact on their teaching practices, autonomy and self-efficacy (Greenfield et al., 2010; Stuart et al., 2011).

We argue, in line with suggestions by previous authors (Dunn, 2019; Saddler & Asaro-Saddler, 2013), that the RTI framework has considerable potential value in teaching writing. This may be particularly the case in early primary school, where students have to contend with developing basic skills in spelling, handwriting and sentence construction alongside the skills necessary to generate and structure content. Transcription skills in first grade are not automatized and children who particularly struggle with these will then not gain the practice they require to develop composition skills. There is, therefore, potential for some children to fall behind their peers from an early stage, unless they are provided with additional support. Equally, the RTI principle of progress monitoring seems important in the context of learning to write. Single-task, occasional writing assessments provide a poor estimate of a child’s writing ability and progress (Van den Bergh et al., 2012).

However, although in principle RTI appears to fit well with writing instruction, in practice both progress monitoring and additional support for struggling students may over-stretch school resources (Castro-Villarreal et al., 2014; Martinez & Young, 2011). This will be particularly the case where a single teacher has sole responsibility for a large, full-range classroom. In this context, recruiting parents to supervise researcher-designed remedial training may facilitate the implementation of a RTI-based program. Parental involvement has actually been defined as a key component of successful RTI-based programs (Stuart et al., 2011), though, to our knowledge, no detailed guidelines on parents’ role has been provided, and no studies have evaluated RTI implementations where parents supervised additional training. There is evidence that parental involvement benefits students’ learning, with estimated standardised effects of around 0.50 (Hattie, 2012, 2015). In writing, research suggests that instructional programs based on parents and children working together significantly improve spelling (Camacho & Alves, 2017; Karahmadi et al., 2013) and even compositional quality (Camacho & Alves, 2017; Robledo-Ramón & García-Sánchez, 2012; Saint-Laurent & Giasson, 2005).

The present study

To our knowledge, no previous research has studied the implementation of RTI-based programs for writing instruction in early elementary school. We therefore report a relatively large and long-term study aimed at establishing evidence for the feasibility and efficacy of implementing a RTI approach to writing instruction in single-teacher, full-range classes. The program started at the beginning of first grade and ended in the middle of second grade. Consistent with RTI’s multi-tiered nature and emphasis on progress monitoring, our program had the following features: (1) Researcher-designed, evidence-based Tier 1 classroom instruction aimed at developing children’s skills in both transcription (spelling and handwriting) and text-composition. (2) Systematic and very regular evaluation of writing performance to identify students’ rate of learning. (3) Additional Tier 2 support for students who, based on this regular evaluation, were identified as falling behind.

Evidence for the success of an instructional program of this form would be that children whose learning initially falls behind their peers’ are effectively supported by Tier 2 instruction. The aim of our research was, therefore, to establish whether additional writing training, in the form of home tasks focused on spelling, handwriting and composition skills, is successful in bringing children who are falling behind back into line with their peers. Success of this additional (Tier 2) training would be evidenced by a) more rapid learning of struggling students relative to peers across Tier 2 training and b) mean performance closer to their peers and rate of learning similar to that of their peers in the period following additional training. Alongside establishing effects on students, we also explored the experiences of both teachers and parents to establish the extent to which they felt the program was manageable and worthwhile.

This study extends our own previous research involving multiple single-case studies from the first two phases of the study (Arrimada et al., 2018), with participants specifically sampled because of slow development of handwriting skills. Results suggested that both transcription and composition skills improved immediately after additional support for students with poor handwriting. The present study reports findings across all students in our sample for the full duration of the study, including post-Tier 2 follow-up.

Method

Design

We evaluated an 18-month RTI-based program of early writing instruction divided into three phases. Phases 1 and 2 ran during first grade and Phase 3 during the first half of second grade. Students remained in the same class groups and with the same teachers throughout. Phase 1 lasted for 13 weeks. During this phase, all students received researcher-designed and teacher-delivered instruction on transcription and strategies for planning and structuring content (Tier 1 in RTI terms). Phase 2 lasted for 10 weeks, with Tier 1 instruction continuing for all students. Students whose rate of learning was significantly below that of their peers received additional Tier 2 instruction in the form of homework tasks supervised by parents/carers. Phase 3 lasted for 15 weeks. As in Phase 1, all students received Tier 1 classroom instruction. This was a follow-up phase to establish whether the performance and rate of learning of struggling students was now closer to that of their peers.

In all phases, students completed progress-monitoring composition tasks at, at minimum, weekly intervals. These tasks were used to identify students who, at the end of Phase 1, were in need of Tier 2 intervention. Writing performance was also measured through more formal narrative writing tasks completed by the students at baseline and after each phase. We also collected qualitative data on parent and teacher experiences.

Participants

The sample comprised 161 Spanish students (83 girls) with mean age of 6 years and 2 months (SD = 3.4 months) at the start of the study. Our sample comprised all students in 8 classes across 3 concertados schools in Northern Spain.

Qualification for Tier 2 intervention was based on predicted performance at the end of Phase 1, established through performance across the regular composition tasks (described below). We selected students with (a) predicted performance in the lowest quartile regardless of rate of learning and/or (b) predicted ability below median and learning rate approaching zero. This was established through linear regression models, fitted separately for each child, with time as predictor and text-quality from the composition tasks as the dependent variable.

Forty students met the first criterion and four more were added on the basis of the second criterion. Parents of 2 students refused permission for their children to participate, and 2 students did not complete any of the intervention tasks. An additional 4 students engaged only patchily with the intervention (completing 3, 5, 6 and 16 of the 22 tasks). These were removed from our sampleFootnote 1 giving a total of 36 students who received Tier 2 intervention (9 female, mean age = 6.6, SD = 3.6), and a comparison group of 125 students (74 female, mean age = 6.7, SD = 3.4) who received just Tier 1 instruction during Phase 2. One Tier 2 student and two comparison students moved to another school in second grade and so their data were absent in Phase 3. Of the 36 students receiving Tier 2 intervention, 17 were already receiving some kind of educational support due to a general development delay, one child was receiving support for a specific language and communication disorder and one for an intellectual disability. Two children in the sample had Latin American heritage and the remainder Spanish heritage.

Students were taught by their regular classroom teachers (N = 8, 6 female, mean age = 47 years and 1 months, SD = 9 years and 9 months). Teachers ranged in experience from 11 to 39 years. The schools sampled in this study were located in, and drew students from families with mid to high socio-economic status.

All parents supervising Tier 2 intervention, except for one, had Spanish as their first language, and Spanish was the home language for all of these students. All parents consented to their children participating in Tier 1 instruction. The parent questionnaire was sent to parents of the 36 children who had engaged with the Tier 2 intervention. We received 32 responses, with missing data for the child who left the school and 3 parents who did not respond.

Educational context

Compulsory education in Spain starts in first grade, although most children attend kindergarten from 3 to 6 years, as was the case for all participants in this study. In kindergarten, students learn to sound and write all letters and to form simple words. Writing instruction in first and second grade focuses strongly on transcription. Instruction emphasises handwriting accuracy and neatness through exercises involving tracing single letters or words. Handwriting fluency is rarely addressed. Students are also taught spelling rules through copy or dictation tasks but they do not receive formal instruction in content planning and/or structuring.

Measures

Progress monitoring probes

Throughout the study students completed regular composition tasks integrated into normal classroom practice. Frequency varied to some extent across classes, with a minimum of one task per week. The teacher first encouraged students to discuss ideas about the topic of their compositions, for about 5 min. Students were then given 10 min to write a narrative. Topics involved events in students’ daily lives or more imaginative story writing and were selected from a list provided by the researchers. This task followed that used with kindergarten and first-grade students by Kent et al., (2014). All students within a class performed the same task. Teachers followed a researcher-provided script when introducing the task.

Text quality was scored on a 6-point scale from 0 points if texts were unreadable, contained a list of unconnected words, or did not represent a meaningful response to the probe task, to a maximum score of 5, which was given for texts that presented a logical sequence of ideas with clarifying, relevant and non-repetitive details, with accurate spelling and accurate and relatively complex grammar, included varied connectors and advanced vocabulary and were well structured. The full scoring rubric and details of how it was developed are provided in Appendix A1 in Supplementary Information and scored example compositions can be found in Appendix A2 in Supplementary Information.

A trained second rater (a post-doctoral researcher in psychology and education), blind to group and time point, scored 17% of texts from each probe task (1254 out of a total of 7288 texts). Inter-rater agreement was 0.91 (Cohen’s weighted Kappa). Rater training involved blind rating of practice sub-samples, meeting to discuss disagreements, and then repeating until agreement prior to discussion reached acceptable levels. A total of around 170 texts (not included in the reliability assessment sample) were rated in this way.

Phase-end assessment

At the start of Phase 1 and at the end of Phases 1, 2 and 3 students were asked to write a narrative for a maximum of 40 min. This was administered by the researcher. There were no constraints on topic: the researcher told the students: “You are going to write a story about whatever you want. You can make it up or recall one that already exists.” Given the age and learning stage of our participants, general prompts of this form avoided problems related to lack of knowledge/ideas or unexpected emotional reactions. Students were reminded to write neatly so readers understand their handwriting and to think carefully before writing. Texts were scored for quality, spelling and handwriting accuracy.

Overall writing quality was assessed through an adapted version of the method used by Cuetos et al. (1996). One point was given for the presence of each of the following: spatial and temporal references, main character, characters’ description, initial happening, emotional responses, any mention of action, sequence of actions, consequences and vocabulary. Total scores ranged from 0 to 10. All texts were rated independently by both the first author and a trained rater, blind to group and time point. Agreement (Cohen’s weighted Kappa) was 0.99 at baseline (start of Phase 1), 0.92 at the end of Phase 1, 0.86 for end of Phase 2, and 0.81 for end of Phase 3.

Text length was the total number of words written, ignoring spelling accuracy. Words were identified as: (a) any string of characters, bounded by spaces or punctuation, that could be identified as letters, or (b) any string that could be read as a Spanish word. See next section for inter-rater reliability.

Spelling accuracy was measured as the proportion of words, as defined above, which were correctly spelled. 50 randomly-selected texts were analysed by a second rater. Inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation and 95% CI) was 1.00 [0.99, 1.00] for word count (text length), 0.96 [0.93, 0.98] for count of misspelled words, and 0.94 [0.89, 0.96] for proportion of correctly spelled words (the reported spelling accuracy measure).

Handwriting quality was assessed on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 to 4. Zero was awarded when the majority of marks on the paper could not be associated with letters. To score 4, all marks should be recognisable letters and the majority of them should be regular. Full details of the scoring scheme can be found in Appendix B in Supplementary Information. Regularity was defined as similarity in letter size and the absence of unclosed loops, shaky strokes or similar features. Two independent raters assessed the handwriting quality of the first 10 words in each text. One of the two raters did not read Spanish, which removed the possibility that agreement was dependent on factors other than handwriting neatness. Interrater agreement (Cohen’s weighted Kappa) was 0.86 at baseline, and 0.83 at the end of Phases 1, 0.86 at the end of Phase 2 and 0.85 at the end of Phase 3.

Teacher experience

At the end of Phase 3 the eight classroom teachers took part in individual semi-structured interviews conducted by the lead researcher. Questions were intended to elicit talk about their personal experience of delivering the Tier 1 program and of administering the regular probe tasks. The interview schedule was constructed after the end of Phase 3. Questions were constructed partly around issues raised by teachers in their various meetings with the lead researcher. The interview schedule was reviewed by the schools’ head teachers. The final version addressed: initial feelings about involvement in the program, perceptions of student experience, experiences of using the intervention materials, and experiences of administering the progress monitoring tasks. It concluded with an open-ended question that aim to elicit additional experiences not covered by the previous questions. All questions can be found in Appendix C in Supplementary Information.

Parent experiences of Tier 2 training

Parents who supported their children with Tier 2 training completed a paper-based questionnaire about their experiences and their perception of their child’s experiences. Wording of questionnaire items was derived in discussion with parents. Table 1 provides questionnaire items. Where there was more than one parent/carer in the student’s home, they either shared completing the questionnaire or it was completed by the parent who took main responsibility for supervising their child’s completion of the Tier 2 tasks.

Instructional content

Tier 1

Tier 1 instruction was delivered by regular classroom teachers throughout all three phases in three 15-min sessions per week (123 sessions). Each session focused on handwriting, spelling, sentence-combining or narrative planning skills. A detailed description of Tier 1 instruction is provided in Appendix D in Supplementary Information. Teachers were given scripted lesson plans for each sessions (see Appendix E in Supplementary Information for an example).

Spelling instruction (23 sessions) was based on previous interventions with elementary students (Berninger et al., 2002; Graham et al., 2002). It addressed three Spanish spelling rules, each one taught in two stages: direct teaching of the rule and spelling practice.

Handwriting instruction (41 sessions) was based on an instructional sequence previously found to be successful with first graders (Berninger et al., 1997). It addressed letter name and shape, alphabet sequence and handwriting fluency.

Sentence-combining training (18 sessions) drew on previous research with elementary students (Limpo & Alves, 2013b; Saddler et al., 2008). It addressed the use of connectors to form complex sentences and three punctuation rules.

Text-planning instruction (41 sessions) focused on how to construct narratives and drew heavily on previous strategy-focused interventions (Arrimada et al., 2019; Harris et al., 2015). Narrative structure was taught in 3 stages: Direct instruction of the strategy for generating and structuring content; modelling of the writing process using the strategy; and individual practice.

Tier 2

Tier 2 training followed a more or less “standard-treatment” approach (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006; King & Coughlin, 2016) but with some degree of individualisation, as detailed below. Additional support was provided to students who learned more slowly than their peers in the form of paper-based activities completed at home, overseen by parents. To facilitate parents’ role, all tasks were researcher-designed and self-contained, meaning that the workbooks included all the exercises and explanatory materials. The instructor was an avatar who provided both theoretical explanations (i.e. written on the books) and clues to complete the activities. Parents were asked only to supervise and support their child.

Training comprised 22 separate tasks, with students completing 2 tasks per week. Tasks were presented on a worksheet and took approximately 20 min to complete. Consistent with the RTI assumption that the same instruction might be more effective if taught in an individualised way, Tier 2 tasks involved additional practice of Tier 1 contents with the exception of sentence-combining,Footnote 2 which was removed from Tier 2 training. The balance of spelling and handwriting tasks was varied across students depending on their needs, based on analysis of their performance in Phase 1.

Handwriting activities were divided into 4 sets, each addressing 7 letters of the alphabet. Each set comprised four kinds of activities. Students first named the letters following the alphabet sequence. They then practiced letter shape by tracing sub-letter forms and whole letters first following numbered arrows and then without help. Finally, students wrote letter combinations as many times as possible in time-limited activities intended to promote handwriting speed.

Spelling training addressed two Spanish spelling rules, matching those that were being taught in Tier 1 classroom instruction during the Tier 2 period. Students first completed activities aimed at observing target words, controlled for frequency, and inferring the rule. Workbooks then contained a direct explanation of the rule and exercises to remember it. Spelling practice was addressed through playful activities in which students were required to write or spell several words. The spelling rules were extracted from the regional curricula for 1st and 2nd grade.

Planning training followed the typical strategy-focused instructional sequence. In the few cases when exercises required writing ideas or texts, students spoke them aloud and their parents wrote down their answers. This prevented transcription difficulties from interfering with composition strategies. The direct instruction and modelling phases alternated, so that after instructing in the first part of a narrative, a mastery model on how to write that part was provided. Direct instruction was presented in the form of a short text at the beginning of the corresponding worksheet. This text instructed students about the three main parts of a story and the structural elements included in each part: introduction (when and where the story happens and who the characters are), development (what happens and how the characters react) and conclusion (how the story ends). These elements were pictured as villages and houses on the way to the top of a Story Mountain, used as a mnemonic. During these phase students completed activities aimed at associating each part of the Story Mountain with the corresponding part of a story (Join each village of the mountain with its name). Modelling was provided by a video in which the first author composed a narrative using thinking aloud protocols. The writer’s verbalizations matched the Story Mountain strategy (The first house of the Introduction village is called “When”. That means the first thing I need to write in my introduction is when the story happens). After watching the video, students wrote their narratives by selecting pictures and tracing the text below them. In the final, individual practice stage, students made up a whole narrative and then self-evaluated it. Appendix F in Supplementary Information shows an example of a planning-instruction worksheet.

Fidelity

Tier 1

Teachers attended an initial 2-h training session in which the lead researcher explained the instructional procedure for each writing component. Afterwards, they were provided teaching plans for all 123 sessions. As requested by the teachers themselves, they received all the intervention materials for the first two phases of the study at the very beginning, just before the start of Tier 1 instruction. Materials for Phase 3 were provided the next year, at the beginning of Tier 1 follow-up instruction. To ensure fidelity, all sessions were audio-recorded. We analysed a random sample of 56 recordings to establish whether activities were delivered as prescribed. Each teaching plan was divided into component parts. We coded each component as either delivered appropriately or inadequately. Across all analysed sessions, median percentage of components delivered appropriately was 89% (interquartile range [77, 100]). Four teachers had median appropriate completion of 100% with medians of 92%, 86%, 80%, and 72% for the others. Across the program, teachers met informally with the lead researcher every week to discuss progress, and for more extended formal meetings at the start of each phase.

Tier 2

Parents attended a one-hour training session, either individually or in small groups, several days before the implementation of Tier 2. In this session, they were provided with a workbook containing all Tier 2 tasks and detailed instructions on how to complete these. The lead researcher first explained the instructional sequence and then went through task instructions, answering parents’ questions. As we detail above, the Tier 2 intervention comprised self-contained tasks supervised by parents. Parents’ contribution was restricted to ensuring that their children understood and completed these tasks, and providing encouragement. Evidence of fidelity therefore is provided by whether or not children completed the tasks successfully. After Tier 2 intervention, we collected all the written outputs. Students completed a median of 22 tasks (M = 21.5, SD = 0.99, range [18, 22]), out of a maximum of 22.

Results

We first describe changes in students’ composition performance across the RTI program. We then report findings from the teacher interviews and parent questionnaire.

Written composition performance

Analysis of both progress monitoring tasks and phase-end measures was by linear mixed effects models (e.g., Baayen et al., 2008). These accommodated the hierarchical structure of our data and, in the case of the progression-probe analysis, remained robust despite varying numbers of observations at each test occasion. Models were implemented in the lme4 R package (Bates et al., 2015; R Core Team, 2021) with maximum likelihood estimation. We adopted “maximal” random effects structures (Barr et al., 2013). For both analyses we tested a series of nested models, comparing model fit with likelihood ratio χ2 tests. Statistical significance of effects was established by evaluation against a t distribution using the Satterthwaite approximation for denominator degrees of freedom, implemented in the lmerTest R package (Kuznetsova et al., 2017).

Successful intervention for students who struggle to learn in Phase 1 would be evidenced by (a) more rapid progress in Phase 2 relative to the comparison group, and (b) a decrease in the difference between the two groups in Phase 3 relative to Phase 1. We tested these hypotheses in subsequent planned contrasts.

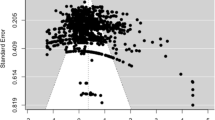

Progress monitoring probes

We evaluated incremental linear mixed effects models with random by-classroom and by-student intercepts and random by-classroom and by-student slopes for Phase and for Time, coded as time of occurrence of probe task in weeks from start of phase. We started with a baseline (intercept only) model (Model 0), then added main effects for Time, Phase and Group (Model 1), and then an interaction term representing the Group by Time interaction at levels of Phase (Model 2). Each subsequent model provided better fit than the preceding model [Model 0 vs. Model 1, χ2(4) = 83, p < 0.001; Model 2 vs. Model 1, χ2(3) = 142, p < 0.001].

Observed means and estimated slopes (from the final, best fitting model) are shown in Fig. 1. This shows improvement in composition quality in both groups during Phase 1, with slightly slower improvement in the students subsequently identified for Tier 2 training. In Phase 2 students receiving Tier 2 training continued to improve while improvement for other writers plateaued. In Phase 3 learning rates were again very similar in the two groups, with very slightly faster learning in the group that had received Tier 2 training. Importantly, the difference between groups was substantially reduced in Phase 3 relative to Tier 1.

Performance of students who were slower to learn and their peers on weekly probe tasks. Note. Points represent sample means, averaged across students, for each probe occasion, with 95% confidence intervals. Regression lines represent parameter estimates from a linear mixed effects full-factorial model with effects for time (week), group and phase (Model 3 as described in the text). The dashed lines represent struggling writers, identified on the basis of Phase 1 performance, who then received additional support in Phase 2

Significance tests on parameter estimates from the final model (Model 2) confirmed statistically significant difference in slopes for the two groups in each of the three phases [Phase 1, t(192) = − 3.6, p < 0.001; Phase 2, t(351) = 7.3, p < 0.001; Phase 3, t(256) = 5.3, p < 0.001]. Estimates for all fixed effect parameters in this model are given in Appendix Table G1 in Supplementary Information. To establish statistical significance for the decrease in difference between Groups in Phase 3 relative to Phase 1 we evaluated a model with main effects for phase and Group, and a dummy variable representing the interaction between Group and Phase 1 versus Phase 3. This interaction effect was statistically significant [t(161) = 4.5, p < 0.001].

Phase-end assessment

In these analyses we predicted changes over time in measures taken from the phase-end narrative writing task (composition quality, word count, spelling and handwriting quality). We predicted these scores on the basis of time (pre Phase 1, post Phase 1, post Phase 2, post Phase 3) and Group and their interaction, in linear mixed effects models with random by-subject and by-classroom intercepts and test-occasion slopes. We tested three nested models starting with fixed effects for the intercept (Model 0), then adding main effects of Group and Time (Model 1), and then a dummy variable representing the Time (pre-phase vs. post-phase) by Group interaction in each of the three phases of the study (Model 2). For all four measures, Model 1 provided significantly better fit than Model 0 (χ2(4) > 48, p < 0.001), and Model 2 provided significantly better fit than Model 1 [quality, χ2(3) = 20, p < 0.001; word count, χ2(3) = 14, p = 0.003; percent correctly spelled words, χ2(3) = 14, p = 0.003; handwriting, χ2(3) = 15, p = 0.002].

Observed means from the Phase-end composition task measures are shown in Fig. 2. With the exception of spelling accuracy, these suggest a similar pattern to that found for performance on the probe tasks. Significance tests for differences in slopes for the two groups in each of the three phases gave the following: Phase 1: quality, t(439) = 1.4, p > 0.05; word count, t(433) = − 1.4, p > 0.05; percent correctly spelled words, t(477) = 3.1, p = 0.002; handwriting, t(458) = − 1.7, p > 0.05. Phase 2: quality, t(433) = 4.1, p < 0.001; word count, t(436) = − 1.4, p = 0.042; percent correctly spelled words, t(420) = 4.0, p = 0.042; handwriting, t(388) = 3.6, p < 0.001. Phase 3: quality, t(425) = 3.3, p < 0.001; word count, t(457) = 1.7, p > 0.05; percent correctly spelled words, t < 1; handwriting, t(379) = 3.2, p < 0.001.

Performance of students who were slower to learn and their peers on phase-end composition task completed at the start of Phase 1 and then at the ends of Phase 1, 2 and 3. Note. Points represent parameter estimates from linear mixed effects full-factorial model with effects for group and time-of-task (Models 2 as described in the text). The dashed lines represent struggling writers, identified on the basis of Phase 1 performance, who then received additional support in Phase 2. P1 end indicates task completed at the end of Phase 1, and so forth

There was evidence, therefore, that across Phase 2—the phase during which weaker writers received Tier 2 instruction—students receiving this instruction improved at significantly greater rate than those in the comparison group, on all four measures. Estimates for all fixed effect parameters are given in Appendix Table G2 in Supplementary Information.

Figure 2 also indicates a decrease in the difference between groups at the end of Phase 3 compared to end of Phase 1 in composition quality, word count, and handwriting quality, but not in percentage of correctly spelled words. We looked specifically at this effect by adding a dummy variable representing the Phase (Phase 1 vs. Phase 3) by group interaction to the main effects model (Model 1) detailed above. This effect was not statistically significant for spelling, but was significant for the other three measures [quality, t(453) = 4.1, p < 0.001; word count, t(435) = 3.3, p < 0.001; percentage of correctly spelled words, t < 1; handwriting, t(85) = 3.5, p < 0.001].

Teachers’ perceptions

We analysed transcripts of interviews using thematic analysis methods based in those described by Braun and Clarke (2006). Teachers’ responses were grouped within the following five themes, which mapped closely to the interview questions.

Initial impressions

All teachers were interested to take part in the program and wanted to find out whether it would benefit the students and themselves (Good impression and good expectations about the program. I was curious to know to what extent it would favour my students and my teaching practice—Teacher 1). However, they were uncertain about how to implement Tier 1 (…the vertigo of not knowing what to do, how to it, if I would do it right—Teacher 5), they thought it might interfere with other classroom activities and they wondered whether students were mature enough (I thought it was very complicated to start such a project when most of the students could barely write—Teacher 6).

Perception of students’ experience

Seven teachers reported that their students responded positively to the program (The children were delighted from the very first day. The activities motivated them a lot, they loved them in general—Teacher 4). Only one teacher reported overall negative student experience. One teacher reported that motivation decreased throughout the program (At the beginning I saw that the students were more motivated…but throughout the year, it became boring since it was a daily routine—Teacher 6). Also, one teacher reported that their students struggled to link the program with normal curricula.

Progress monitoring measures

Teachers’ views about these tasks were mixed. Several regarded them as repetitive and too difficult (“It was the most tedious task for them because it was repetitive. Beginning this activity in first grade…children don’t know…thinking about how to write is too hard for them”—Teacher 3). Two teachers explicitly stated that their students did not like these tasks but one reported their students liking them. Two teachers found these tasks useful (Thanks to these tasks, progress was monitored and we clearly saw the development. In some cases, this development was striking—Teacher 8). All teachers emphasized the need to vary the topic to maintain students’ interest (When you gave them different proposals, they invented, imagined, wrote about other experiences…—Teacher 5). There was a general belief that the probe tasks would be more appropriate in higher grades (“I would do this in second grade and give them more time, enlarge the task”—Teacher 4).

Strengths and weaknesses

All teachers agreed that the materials provided were the strongest point, since they supported theory and were highly motivating (“Materials were very good because they were interactive. Students found it very motivating to do things by themselves”—Teacher 2). All teachers but one reported they would use these materials in their future teaching practice, particularly the planning ones. Other strong points were the clear instructional sequence (Teacher 4), the utility of the program to support learning (teacher 6) and its validity to detect difficulties (Teacher 2). Teachers also valued the scripted sessions (i.e., “The handbook was very clear and I had no doubt about it. It was very well organized”—Teacher 1). Teacher’s biggest concern was the lack of time. They reported feeling sometimes burdened and being forced to take time away from other activities (i.e. “Due to the little time we had to work with the students…sometimes I felt burdened, really burdened”—Teacher 7). Another weakness was that, according to the teachers, the students lacked the cognitive capacity to face such a program (i.e., “It is a great handicap to apply it so early because students are childish and immature”—Teacher 2). Two teachers also reported the program being too long. Only Teacher 3 mentioned the progress monitoring tasks as a weakness, though most had previously expressed some frustration at their frequency.

Recommendations

Seven teachers reported that they would recommend the program. Reasons include its systematic structure (Teacher 4), students’ positive responses (Teachers 5 and 8) and its innovative nature (Teacher 8). One teacher recommended starting in later grades and adapting it to classroom curricula. Another teacher suggested shortening the program. Only Teacher 2 said that they would not recommend the program.

Parents’ perceptions

Table 1 presents frequencies of responses and the coding system. Correlation among scores on questionnaire items can be found in Appendix Table G3 in Supplementary Information.

Most parents reported being surprised that their child was selected to receive Tier 2 training, though very few reported seeing this support as unnecessary. Most parents reported feeling happy for their child to receive extra help and reinforce classroom practice. Some expressed concerns about their child’s lower achievement and their own lack of time and/or experience. Unexpectedly, most parents did not report concern about their child’s reactions towards the program. The majority reported that their child felt either happy or indifferent about being selected.

Overall, parents reported frequent and positive interactions with their child over the program. Most parents reported finding no difficulty in keeping their child’s attention and explaining the exercises, suggesting these were understandable. 44% of parents reported an increase in their child’s motivation towards writing following Tier 2 training. Only 3 parents indicated that their child enjoyed few or none of the activities. Parents tended not to report a change in their relationship with their child following Tier 2 training. However, parents were more likely to report an improved relationship with the school. Parents did not report helping their children with writing tasks more often after the end of the Tier 2 program, though they reported feeling more confident and willing to do so.

Finally, parents reported positive experiences of the program and stated that they would participate again. Only one parent reported a negative experience. A substantial majority of families reported finding Tier 2 useful and appropriate for their child’s academic level, although some reported the tasks being either too easy or too difficult.

Discussion

This study describes a rigorous implementation of an RTI approach to teaching writing at the beginning of compulsory education. Previous research has explored the effectiveness of approaches to teaching written composition in first grade by evaluating relatively short interventions delivered to either whole classes or small groups (Arrimada et al., 2019; Harris et al., 2015; Zumbrunn & Bruning, 2013). Interventions are claimed as successful if average performance across all intervention students increases relative to controls. Our approach here was different. We took approaches to writing instruction previously found successful and applied them across a longer period of time, monitoring students’ progress and remediating when students’ progress fell behind that of their peers. We aimed to establish the feasibility and potential value of this RTI approach implemented within single-teacher classrooms, with parents recruited to supervise the additional training.

We believe our study provides preliminary evidence that parent-supported Tier 2 intervention is effective in bringing struggling students’ performance back into line with their peers'. First, we found that composition quality improved for all students across the program. Mean text length increased across the whole sample, as did the number of features associated with good narratives (increases of 4.1 features in the comparison group and 5.5 in the intervention group—Fig. 2). This suggests that students learned skills for developing narrative structure alongside transcription. Thus, the instructional approach adopted seems to have potential in the context of an extended, teacher-implemented program.

Second, and more importantly, we found that Tier 2 students showed improved learning rate and gained substantially in overall performance, relative to their peers. Across Phase 2 performance on the phase-end narrative task improved very substantially for the Tier 2 intervention group, while the comparison group showed much more modest improvement (Fig. 2). Also, composition quality in the progress monitoring tasks showed accelerated learning during the Tier 2 period for students who received this additional support (i.e. who were slower learners in Phase 1 (Fig. 1). This provides reasonable evidence that improvement resulted from Tier 2 training.

The only measure that did not show improvement in the Tier 2 sample in Phase 2, relative to the comparison group, was the accuracy of the spelling in the students’ texts. This might be because first-grade normal curriculum already has a strong focus on spelling. Both conditions were already close in performance at the beginning of Phase 2. Simply adding some spelling homework was not enough for weak writers to show significantly more improvement that their average peers. A second explanation might be related to the fact that our spelling instruction focused strongly on direct teaching of spelling rules. Embedding spelling instruction in context (e.g., O’Flahavan & Blassberg, 1992) may produce stronger results when spelling is assessed in the context of a composition task. Spelling within written composition is in part determined by the child’s spelling ability but is also determined by the words that the child chooses to write, and an interaction between these two factors. Improved composition performance across Phase 3 in the Tier 2 group was associated with an increase in productivity and overall text quality. This may be achieved without extending the vocabulary that they use to express their ideas beyond those words that they felt confident to spell correctly.

Across Phase 2, Tier 2 students showed improvement in the neatness of their handwriting, alongside with increases in the length and sophistication of their text. This is consistent with previous findings suggesting that handwriting training results in students including appropriate rhetorical features in their texts (Limpo et al., 2018). Handwriting instruction is associated with significant gains in text quality (see meta-analysis by Santangelo & Graham, 2016).

The comparison group did not show improvement during Phase 2. This may have resulted from the fact that Tier 1 instruction in Phase 2 largely reproduced the instructional activities in Tier 1 instruction in Phase 1. However students in the comparison group did show improvement across Phase 2 in performance on the phase-end narrative task.

Our program was implemented in single-teacher classes, with parents’ support. This demanded time and effort from teachers and parents, and so buy-in from both groups was essential to the success of the program. Teachers’ and parents’ experiences suggest, with some caveats, that this was achieved. Teachers, with some reservations, found the program feasible to deliver and believed it benefitted their students. Teachers’ experiences in our study were similar to those of elementary grade teachers who implement RTI-based reading programs and find that the number of students who struggled dropped after receiving multi-tiered support (Greenfield et al., 2010; Stuart et al., 2011). In the present study, teachers also saw the program as valuable for their future teaching and would recommend it to colleagues. However, as in previous studies, teachers sometimes felt overwhelmed by the demands that the program placed on their time (Castro-Villarreal et al., 2014; Martinez & Young, 2011).

Negative perception of the progress monitoring tasks may in part have been due to the form that the task took in our particular implementation, rather than having to implement progress monitoring tasks per se. Tasks of the form used in the present study (10 min narrative compositions in response to a very general prompt) have also been used in previous research with similar aged writers (Kent et al., 2014). However alternatives exist. For example Coker and Ritchey (2010) describe and evaluate a measure designed to be used by teachers for progress monitoring in a RTI programs delivered in kindergarten and first-grade. This requires children writing two sentences in response to two separate prompts, with a 3 min time limit per sentence. Tasks of this form do not permit assessment of the child’s ability to form written narrative structure. However teachers, and students, may have found them less motivationally demanding. Some teachers also believed their students were not mature enough to start learning composing skills. This might be expected in educational contexts where normal classroom practice focuses almost exclusively on transcription, as is the case in Spain (Cano & Cano, 2012).

Teachers’ perceptions and experiences are likely to be in part due to impacts of the demands of delivering the program on their self-efficacy. Research suggests that teachers’ self-efficacy for teaching writing is often not very high and, at least in some educational contexts, they feel their training gives them inadequate preparation (Brindle et al., 2016; De Smedt et al., 2016; Graham et al., 2008; Rietdijk et al., 2018; Sánchez-Rivero et al., 2021). The program that we asked teachers to implement required instruction in written composition at an earlier stage than they were used to, and the implementation of unfamiliar lesson plans and curriculum-based assessment. These further demands are likely to have reduced teacher self-efficacy still further.

Preliminary findings about parents’ perceptions suggest that parents who supported the Tier 2 training were broadly positive about the experience. They reported that the program benefitted their children and that they would be willing to participate again. Parents’ concerns were mostly focused on lacking time or experience to help their children with the tasks and, particularly, the fact that their child was showing slower learning. Overall, teachers’ and parents’ perceptions point to the feasibility of our approach in single-teacher full-range classes. Note, however, that parents’ and teachers’ roles were very different. While teachers were instructors who played an active role in delivering instructional content, the Tier 2 intervention relied on the completion of instructionally self-contained tasks. Parents’ role was mainly to ensure that their child understood what they were being asked to do and that the tasks were completed. This should be borne in mind when making claims about the feasibility of our program in other contexts.

We believe, therefore, that our findings, provide preliminary evidence for the value of an RTI approach to writing instruction from the start of school, based on continuous progress monitoring and then support for students who were slow to develop writing skills at the start of first grade.

Limitations and future research

Reviewers of a previous version of this paper questioned the validity of our tool for assessing parents’ response to the intervention. A detailed analysis (and therefore, strong claims) about parents’ perceptions on the implementation of RTI-based programs was beyond the scope of this study. Our parent questionnaire data do, we believe, provide evidence that parents saw our program as manageable and worthwhile. However, future research might usefully conduct open-ended interviews and / or develop more robust psychometric measures for establishing parents’ beliefs about the program. Parents’ perception of and experiences with the Tier 2 intervention have, of course, direct impact in whether or not the training is successful.

With regards to the main focus of our paper: Although our findings are consistent with the effectiveness of the parent-supported Tier 2 training, other explanations are possible. It is possible that improvement in this group during Tier 2 was purely maturational and independent of instruction. Our study did not control for this possibility. In the context of our study, with researcher-provided instructional materials used throughout and continual monitoring of student progress, we could not justify a group of students identified as needing additional support not then receiving this support.

A more general question is whether the approach as a whole is more effective in developing students’ writing than a curriculum without regular progress monitoring and multi-tiered instruction. Future research should involve a large-scale comparison of the RTI approached with schools that follow a traditional curriculum. We see our relatively large-sample pilot study as a necessary initial step before performing a full randomized controlled, multi-school evaluation of this approach. The methods and findings of the research reported in this paper demonstrate feasibility, and therefore provide the basis and justification for such a study. Providing that future controlled studies actually confirm that our approach is effective, it would also be interesting to test the individual efficacy of each component of our program, to complement positive results on its current whole-package nature.

Finally, results of this study should be treated with caution when generalising them to other educational settings. First, all participants came from families with mid to high socio-economic status. Although supervision of Tier 2 tasks did not require skills above general literacy, there is a possible relationship between socio-economic status and motivation to engage. Second, it is worth noting that both Tier 1 and Tier 2 instructional content was tailored to the specific educational context. All students in the present study had received some instruction in handwriting, letter knowledge, and basic spelling prior to school entry. Results might differ in educational systems where students do not receive any writing instruction prior to starting school.

Availability of data and materials

Subject to the acceptance of the editor, the researcher would be happy to make all data and materials public either in a space provided by the journal itself or in the research team webpage.

Notes

We also repeated analysis with data from these four students included in our Tier 2 sample. Findings were substantively equivalent across all analyses with the exception that an effect of Tier 2 intervention on numbers of words spelled accurately in the phase-end narrative writing task that was small and marginally significant in the reduced sample failed to reach statistical significance when these four students were added.

Sentence combining was omitted first because this allowed more time to focus on handwriting and spelling skills, which was necessary, given that some children were failing to produce sentences of any form, and second, because supervision of this task required a level of skill that we could not assume in the children’s parents.

References

Arrimada, M., Torrance, M., & Fidalgo, R. (2018). Supporting first-grade writers who fail to learn: multiple single-case evaluation of a Response to Intervention approach. Reading and Writing, 31(4), 865–892. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9817-x

Arrimada, M., Torrance, M., & Fidalgo, R. (2019). Effects of teaching planning strategies to first-grade writers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(4), 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12251

Baayen, R. H., Davidson, D. J., & Bates, D. M. (2008). Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language, 59(4), 390–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005

Barnes, A. C., & Harlacher, J. E. (2008). Clearing the confusion: Response-to-Intervention as a set of principles. Education and Treatment of Children, 31(3), 417–431. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.0.0000

Barr, D. J., Levy, R., Scheepers, C., & Tily, H. J. (2013). Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language, 68(3), 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Berkeley, S., Bender, W., Gregg, L., & Saunders, L. (2009). Implementation of response to intervention. A snapshot of progress. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219408326214

Berninger, V. W., Nagy, W., & Beers, S. F. (2011). Child writers’ construction and reconstruction of single sentences and construction of multi-sentence texts: Contributions of syntax and transcription to translation. Reading and Writing, 4(2), 151–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-010-9262-y

Berninger, V., Vaughan, K. B., Abbott, R. D., Abbott, S. P., Rogan, L. W., Brooks, A., Reed, E., & Graham, S. (1997). Treatment of handwriting problems in beginning writers: Transfer from handwriting to composition. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(4), 652–666. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.4.652

Berninger, V. W., Vaughan, K., Abbott, R. D., Begay, K., Coleman, K. B., Curtin, G., Hawkins, J. M., & Graham, S. (2002). Teaching spelling and composition alone and together: Implications for the simple view of writing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 291–304.

Berninger, V. W., & Winn, W. (2006). Implications of advancements in brain research and technology for writing development, writing instruction, and educational evolution. In C. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 96–114). Guildford Press.

Bingham, G. E., Quinn, M. F., & Gerde, H. K. (2017). Examining early childhood teachers’ writing practices: Associations between pedagogical supports and children’s writing skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 39, 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.01.002

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brindle, M., Graham, S., Harris, K., & Hebert, M. (2016). Third and fourth grade teacher’s classroom practices in writing: A national survey. Reading and Writing, 29(5), 929–954. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9604-x

Brown-Chidsey, R., & Steege, M. (2005). Response to Intervention. Guildford Press.

Burns, M. K., Appleton, J. J., & Stehouwer, J. D. (2005). Meta-analytic review of responsiveness-to-intervention research: Examining field-based and research-implemented models. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 23(4), 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/073428290502300406

Camacho, A., & Alves, R. A. (2017). Fostering parental involvement in writing: Development and testing of the program cultivating writing. Reading and Writing, 30(2), 253–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-016-9672-6

Cano, A., & Cano, M. (2012). Prácticas docentes para el aprendizaje inicial de la lengua escrita: De los currículos al aula [Teaching practices for the initial learning of writing language: From curricula to classrooms]. Docencia e Investigación, 22, 81–96.

Castro-Villarreal, F., Rodriguez, B. J., & Moore, S. (2014). Teachers’ perceptions and attitudes about Response to Intervention (RTI) in their schools: A qualitative analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 40, 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.02.004

Coker, D. L., & Ritchey, K. D. (2010). Curriculum-based measurement of writing in kindergarten and first grade: An investigation of production and qualitative scores. Exceptional Children, 76(2), 175–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291007600203

Cuetos, F., Sánchez, C., & Ramos, J. L. (1996). Evaluación de los procesos de escritura en niños de educación primaria. Bordón, 48(4), 445–456.

Cutler, L., & Graham, S. (2008). Primary grade writing instruction: A national survey. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(4), 907–919. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012656

De Smedt, F., Van Keer, H., & Merchie, E. (2016). Student, teacher and class-level correlates of Flemish late elementary school children’s writing performance. Reading and Writing, 29(5), 833–868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9590-z

Dockrell, J. E., Marshall, C. R., & Wyse, D. (2016). Teachers’ reported practices for teaching writing in England. Reading and Writing, 29(3), 409–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9605-9

Dunn, M. (2019). What are the origins and rationale for tiered intervention programming? In M. Dunn (Ed.), Writing instruction and intervention for struggling writers: Multi-tiered systems of support (pp. 1–15). Cambridge Scholar Publishers.

Dunsmuir, S., & Blatchford, P. (2004). Predictors of writing competence in four to seven year old children. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74(3), 461–483. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007099041552323

Fayol, M. (1999). From on-line management problems to strategies in written composition. In M. Torrance & G. Jeffery (Eds.), The cognitive demands of writing: Processing capacity and working memory effects in text production (pp. 15–23). Amsterdam University Press.

Fidalgo, R., & Torrance, M. (2018). Developing writing skills through cognitive self-regulation instruction. In R. Fidalgo, K. Harris, & M. Braaksma (Eds.), Design principles for teaching effective writing (pp. 89–118). Brill Editions.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. (1981). Plans that guide the composing process. In C. H. Frederiksen & F. Dominic (Eds.), Writing: The nature and development and teaching of written communications (Vol. 2 Writing: Process, development and communication). Erlbaum.

Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2006). Introduction to response to intervention: What, why, and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly, 41(1), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.41.1.4

Graham, S., & Harris, K. (2018). Evidence-based writing practices: A meta-analysis of existing meta-analysis. In R. Fidalgo, K. Harris, & M. Braaksma (Eds.), Design principles for teaching effective writing: Theoretical and empirical grounded principles. Brill Editions.

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & Chorzempa, B. (2002). Contribution of spelling instruction to the spelling, writing, and reading of poor spellers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 669–686. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0663.94.4.669

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., Mason, L., Fink-Chorzempa, B., Moran, S., & Saddler, B. (2008). How do primary grade teachers teach handwriting? A National Survey. Reading and Writing, 21(1–2), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-007-9064-z

Graham, S., & Santangelo, T. (2014). Does spelling instruction make students better spellers, readers, and writers? A meta-analytic review. Reading and Writing, 27(9), 1703–1743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-014-9517-0

Greenfield, A. R., Rinaldi, C., Proctor, C. P., & Cardarelli, A. (2010). Teachers’ perceptions of a response to intervention (RTI) reform effort in an urban elementary school: A consensual qualitative analysis. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 21(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207310365499

Harris, K. R., & Graham, S. (1996). Making the writing process work: Strategies for composition and self-regulation (2nd ed.). Brookline Books.

Harris, K., & Graham, S. (2018). Self-regulated strategy development: Theoretical bases, critical instructional elements and future research. In R. Fidalgo, K. Harris, & M. Braaksma (Eds.), Design principles for teaching effective writing (pp. 119–151). Brill Editions.

Harris, K., Graham, S., & Adkins, M. (2015). Practice-based professional development and Self-Regulated Strategy Development for Tier 2, at-risk writers in second grade. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 40, 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.02.003

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. Routledge.

Hattie, J. (2015). The applicability of visible learning to higher education. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 1(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000021

Jiménez, J. E., & Hernández-Cabrera, J. A. (2019). Transcription skills and written composition in Spanish beginning writers: Pen and keyboard modes. Reading and Writing, 32(7), 1847–1879. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9928-4

Juel, C., Griffith, P. L., & Gough, P. B. (1986). Acquisition of literacy: A longitudinal study of children in first and second grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(4), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.78.4.243

Karahmadi, M., Shakibayee, F., Amirian, H., Bagherian-Sararoudi, R., & Maracy, M. R. (2013). Efficacy of parenting education compared to the standard method in improvement of reading and writing disabilities in children. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 8(1), 51–58.

Kellogg, R. T. (1990). Effectiveness of prewriting strategies as a function of task demands. The American Journal of Psychology, 103(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.2307/1423213

Kent, S., Wanzek, J., Petscher, Y., Al Otaiba, S., & Kim, Y. S. (2014). Writing fluency and quality in kindergarten and first grade: The role of attention, reading, transcription, and oral language. Reading and Writing, 27(7), 1163–1188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-013-9480-1

Kim, Y. S. (2020). Structural relations of language and cognitive skills, and topic knowledge to written composition: A test of the direct and indirect effects model of writing. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(4), 910–932. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12330

Kim, Y. S., & Park, S. H. (2019). Unpacking pathways using the direct and indirect effects model of writing (DIEW) and the contributions of higher order cognitive skills to writing. Reading and Writing, 32(5), 1319–1343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9913-y

Kim, Y. S. G., & Schatschneider, C. (2017). Expanding the developmental models of writing: A direct and indirect effects model of developmental writing (DIEW). Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000129

King, D., & Coughlin, P. K. (2016). Looking beyond RtI standard treatment approach: It’s not too late to embrace the problem-solving approach. Preventing School Failure, 60(3), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2015.1110110

Koster, M., Tribushinina, E., de Jong, P. F., & van den Bergh, H. (2015). Teaching children to write: A meta-analysis of writing intervention research. Journal of Writing Research, 7(2), 249–274. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2015.07.02.2

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest Package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13

Limpo, T., & Alves, R. A. (2013a). Modeling writing development: contribution of transcription and self-regulation to Portuguese students. Text Generation Quality, 105(2), 401–413. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031391

Limpo, T., & Alves, R. A. (2013b). Teaching planning or sentence-combining strategies: Effective SRSD interventions at different levels of written composition. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(4), 328–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.07.004

Limpo, T., Parente, N., & Alves, R. A. (2018). Promoting handwriting fluency in fifth graders with slow handwriting: A single-subject design study. Reading and Writing, 31(6), 1343–1366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-017-9814-5

Martinez, R., & Young, A. (2011). Response to Intervention: How is it practiced and perceived. International Journal of Special Education, 26(1), 44–52.

McCutchen, D. (1996). A capacity theory of writing: Working memory in composition. Educational Psychology Review, 8(3), 299–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01464076

O’Flahavan, J. F., & Blassberg, R. (1992). Toward an embedded model of spelling instruction for emergent literates. Language Arts, 69(6), 409–417.

R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (4.0.4 "Lost Library Book"). R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Rietdijk, S., van Weijen, D., Janssen, T., van den Bergh, H., & Rijlaarsdam, G. (2018). Teaching writing in primary education: Classroom practice, time, teachers’ beliefs and skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(5), 640–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000237

Rijlaarsdam, G., & Couzijn, M. (2000). Writing and learning to write: A double challenge. In R. Simons, J. van der Linden, & T. Duffy (Eds.), New learning (pp. 157–189). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47614-2_9

Rijlaarsdam, G., Van den Bergh, H., Couzijn, M., Janssen, T., Braaksma, M., Tillema, M., Van Steendam, E., & Raedts, M. (2011). Writing. In S. Graham, A. Bus, S. Major, & L. Swanson (Eds.), Handbook of educational Psychology: Application of educational psychology to learning and teaching (pp. 189–228). American Psychlogical Society.

Rinaldi, C., Averill, O. H., & Stuart, S. (2011). Response to Intervention: Educators’ perceptions of a three-year RTI collaborative reform effort in an urban elementary school. Journal of Education, 191(2), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/42744205

Robledo-Ramón, P., & García-Sánchez, J. N. (2012). Preventing children’s writing difficulties through specific intervention in the home. In W. Sittiprapaporn (Ed.), Learning disabilities. InTech Europe.

Saddler, B., & Asaro-Saddler, K. (2013). Response to Intervention in writing: A suggested framework for screening, intervention, and progress monitoring. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 29(1), 20–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2013.741945

Saddler, B., Behforooz, B., & Asaro, K. (2008). The effects of sentence-combining instruction on the writing of fourth-grade students with writing disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 42(2), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0031030111010138

Saddler, B., Ellis-Robinson, T., & Asaro-Saddler, K. (2018). Using sentence combining instruction to enhance the writing skills of children with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 16(2), 191–202.

Saint-Laurent, L., & Giasson, J. (2005). Effects of a family literacy program adapting parental intervention to first graders’ evolution of reading and writing abilities. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 5(3), 253–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798405058688

Sánchez-River, R., Alvez, R. A., Limpo, T., & Fidalgo, R. (2021). Analysis of a survey on the teaching of writing in compulsory education: Teachers’ practices and variables. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 79(279), 321–340. https://doi.org/10.22550/rep79-2-2021-01

Santangelo, T., & Graham, S. (2016). A comprehensive meta-analysis of handwriting instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 225–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9335-1

Stuart, S., Rinaldi, C., & Higgins-Averill, O. (2011). Agents of change: Voices of teachers on response to intervention. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 7(2), 53–73.

Teberosky, A., & Sepúlveda, A. (2009). El texto en la alfabetización inicial. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 32(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1174/021037009788001770

Torrance, M., & Galbraith, D. (2006). The processing demands of writing. In Handbook of writing research (pp. 67–82). Guildford Press.

Van den Bergh, H., Maeyer, S., van Weijen, D., & Tillema, M. (2012). Generalizability of text quality scores. In E. Van Steendam, M. Tillema, G. Rijlaarsdam, & H. van den Bergh (Eds.), Measuring writing: Recent insights into theory, methodology and practice (pp. 23–32). Brill.

Zumbrunn, S., & Bruning, R. (2013). Improving the writing and knowledge of emergent writers: The effects of self-regulated strategy development. Reading and Writing, 26(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-012-9384-5

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness [Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad de España] Grant EDU2015-67484-P MINECO/FEDER, awarded to the third author. The funders had no direct input into the design and implementation of the research. The first author has benefited from a research Grant (FPU14/04467) awarded by the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sports [Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte de España].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arrimada, M., Torrance, M. & Fidalgo, R. Response to Intervention in first-grade writing instruction: a large-scale feasibility study. Read Writ 35, 943–969 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10211-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10211-z