Abstract

Writing on-demand, text-based analytical essays is a challenging skill to master. Novice writers, such as the sixth grade US students in this study, may lack background knowledge of how to compose an effective essay, the self-efficacy skills, and the goal setting skills that will help with completing this task in accomplished ways. This sequential mixed-method study explored the impact of guiding a predominantly Redesignated English Learner group of students in a large, urban, low-SES school district in a timed, on-demand essay into a multiple draft process paper through a self-assessment, planning and goal setting, and reflection process as they revised this process paper over a three week period. Both treatment and comparison students completed a pre-test on demand writing assessment, a pre and post self-efficacy in writing survey, and a post-test on demand writing assessment. Students in both conditions were participating in a year-long writing intervention called The Pathway to Academic Success, developed and implemented by the UC Irvine site of the National Writing Project (UCI Writing Project), during the 2017–2018 school year and received identical training from their teachers on how to revise a pre-test essay. However, only the treatment group engaged in self-assessment, planning and goal setting, and reflection during this revision process. Students in the treatment condition demonstrated improved self-efficacy in the writing sub-domain of revision (p < .05) and had statistically significant greater gains on the post-test writing assessment (r = .57; p < .001). These results suggest that engaging students in a planned revision process that includes student reflection, planning, and goal setting before revision, and reflection and self-assessment after revision, positively impacts self-efficacy and writing outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A person’s self-efficacy, or beliefs about his or her ability to succeed in a specific domain (Bandura, 1997, 2006), plays an important role in both how well a person performs and how long he or she persists at a particular task, especially when the task is complex. Few academic tasks may be as difficult as those required of students in secondary school to demonstrate mastery of the text based analytical writing called for by the Common Core State Standards (Barzilai et al., 2018; Biancarosa & Snow, 2004; Graham & Perin, 2007; National Governors Association, 2010; Olson et al., 2012). Greater mastery of this skill has been highly correlated with postsecondary success and career readiness (Perin et al., 2017). From grade 6 through 12, students are expected to demonstrate increasing complexity as they “write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence” (NGA, 2010, p. 42). Sub-skills to master this standard include conducting extensive research, discerning fact from opinion, writing a defensible and nuanced claim, organizing essays logically, and revising their papers for clarity.

Recent results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress for Writing (NCES, 2012) highlight the need to help students become proficient writers, especially in the area of analytical writing and revision which students often find especially challenging (Olson et al., 2012). Only about 27% of the nation’s students—and only 1% of English Learners (ELs)—scored proficient or advanced in writing (NCES, 2012). This is cause for concern, because being able to write well is an important skill for success in both higher education and the workplace across a variety of disciplines and industries (National Commission on Writing for America’s Families, Schools, and Colleges, 2004). Additionally, the achievement gap between our English learners and their English only peers is an issue of equity and access.

ELs represent the fastest growing segment of the K-12 population with the largest increases occurring in grade 7–12 (U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Educational Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, 2017). In 2013–14, over 9% of K-12 public school students were ELs. California leads the nation with almost 23% ELs (U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Educational Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, 2016). Although ELs in the United States speak more than 350 languages, 73% speak Spanish as their first language (Batalova & McHugh, 2010), 40% have origins in Mexico (Hernandez, Denton, & Macartney, 2008), and 60% of ELs in grades 6 through 12 come from low-income families (Batalova et al., 2005; Capps et al., 2005). The largest numbers of ELs in our schools today are referred to as long-term ELs (LTELs) (Menken & Kleyn, 2009). According to Olsen (2010), these are students who have been educated in the United States since age six, are doing poorly in school, and have major gaps in knowledge because their schooling was disrupted. In Olsen’s study of 175,734 ELs, the majority (59%) were LTELs who were failing to acquire academic language and struggling to do well in high school. They may come from homes where the primary language is not English, but they themselves may speak English only or they may switch between multiple languages and still have features in their writing attesting to their multilingual status (Valdés, 2001). Limited in their knowledge of academic registers in any language, these students are often mainstreamed into regular English language arts classrooms, though they may be disadvantaged in not only writing skills, but also in soft skills.

One possible contributor to flat-lined scores between administrations of the NAEP-Writing, is the lack of self-efficacy or motivation to perform well on standardized tests for all secondary writers, but particularly for English learners. Kiuhara et al. (2009) found that students are constrained by more complex essay writing tasks and timed on-demand tasks due to textual, affective, and genre constraints. Students often are either given very brief instructions/prompts, may be unfamiliar with or under-practiced in the genre being assessed, or are overwhelmed by the information given to them in these settings (Blake et al., 2016). The fact that students may not know how to approach the writing task or even understand what is expected of them in these situations is a problem that must be addressed. Because text-based analytical writing is a gatekeeper for college access and persistence and a “threshold skill” for hiring and promotion for salaried workers (National Commission on Writing for America’s Families, Schools, and Colleges, 2004), failure to close these achievement gaps in academic writing will have serious social and economic consequences. Again, in these circumstances, a student’s self-efficacy plays a large role in completing these tasks.

Self-efficacy is particularly important in completing complex writing tasks. In a study exploring self-efficacy in writing, Pajares and colleagues (2007) found that how students interpret the results of their own past writing performance, such as how successful they believe they were at completing a writing task, can make a key contribution to their sense of self-efficacy. In fact, Graham and colleagues (2018) found that students’ beliefs (i.e., sense of self-efficacy) contributed to 10% of the variance in predicting students’ writing outcomes and the percentage is even higher (16.3%) for students with disabilities. On-demand writing, ubiquitous in educational settings, compounds the impact of self-efficacy in writing as students have the added pressure to perform cognitively demanding tasks in a short amount of time that may not mirror the more thoughtful stage process that they are given during regular instruction to take a paper through the writing process, which includes pre-writing, drafting, revising, and editing phases. When students are often asked to revise papers before they submit them for evaluation they are asked to improve their drafts through careful reading and writing that globally impacts their message or purpose for writing the paper. However, few students give themselves enough time to revise their writing during the more intense situations of timed writing assessments. Moreover, even when they do have time to revise their efforts may actually have the opposite effect. Changes they make are constrained by the time they have to reflect on the impact the revision has on the rest of the paper and make more local changes that may or may not help with the overall assessment of the quality of the paper (Worden, 2009).

The current study, a sequential mixed methods design study, on testing the impact of self-efficacy in essay writing is an extension of a large-scale intervention called The Pathway to Academic Success, developed and implemented by the UCI Writing Project, that aims to close the achievement gap for English learners in mainstreamed ELA classrooms and their native English speaking peers, particularly in the area of text-based analytical writing by demystifying the process that expert readers and writers use to approach domain-specific tasks, targeting teacher professional development, and fostering students’ habits of mind. By focusing on students’ self-efficacy in writing (SEW) in classroom settings, this work can positively impact teachers’ practices and influence students’ motivation and ability to write analytically. To this end, we focus on answering the following three research questions:

-

1.

Do students with higher self-efficacy have better writing outcomes?

-

2.

What is the impact of students’ self-assessment, planning and goal setting, and reflection on their self-efficacy in writing as they revise a text-based analytical essay?

-

3.

What do students cite as most helpful in revising their writing and how does this contribute to their self-efficacy?

Literature review

The following section reviews the research literature that informs our study. First, we review the concept of self-efficacy in writing to address the first research question. Then, we review the literature on students’ self-assessment, planning and goal setting, and reflection in relation to revision of writing in order to study the second research question. Finally, we discuss factors that are known to impact students’ successful revision of writing such as teacher instruction, motivation, prior knowledge, and conditions of the writing task to explore the third question.

Self-efficacy in writing

As mentioned previously, a person’s self-efficacy, or beliefs about his or her ability to succeed in a specific domain (Bandura, 1997, 2006), influences how anxious people feel, the goals that they set for themselves, and the strategies that they adopt when working towards those goals. A greater sense of self-efficacy tends to correlate with lower levels of anxiety, the use of more effective learning strategies, greater enjoyment of the task, a greater willingness to seek help when needed, and better overall performance (Bong, 2006; Sanders-Reio et al., 2014; Williams & Takaku, 2011).

Pajares and colleagues (2007) explored Bandura’s (1997) four hypothesized sources of self-efficacy beliefs—mastery experiences, social persuasion, vicarious experiences, and anxiety—Pajares and colleagues found that, while all four factors were significantly correlated with students’ self-efficacy in writing, perceived mastery experiences were the greatest predictor of writing self-efficacy regardless of gender or grade level. In other words, how students interpret the results of their own past performance, such as how successful they believe they were at completing a similar task, makes a key contribution to their sense of self-efficacy. Although this has led to some interventions that focus on giving praise and encouraging students to evaluate themselves in positive ways as a method of improving self-efficacy, theorists and researchers have increasingly emphasized the importance of concrete skill development and the opportunities that it provides for genuine success experiences (Pajares et al., 2007). Such experiences provide powerful support for increasing students’ self-efficacy and equip students with the tools they can use to succeed in future writing tasks.

Self-assessment

Studies which focus on the relationship of students’ self-efficacy on past performance and its impact on future performance have explored a variety of activities and their potential for increasing student self-efficacy in writing. One of the most notable of these is self-assessment, which occurs when people evaluate their own work, identify disparities between their current and desired performance, and reflect upon ways in which they can improve (McMillan & Hearn, 2008). Guiding students through this self-reflective process and supporting their development of self-assessment skills gives students a sense of agency and control over their own learning, which, in turn, can heighten student motivation and self-efficacy (Panadero et al., 2016). Self-assessment can be conducted and expressed in both spoken (e.g., self-explanation) and/or written form (e.g., reflection); it is conjectured that students who are able to articulate their declarative knowledge around task concepts are better able to convert this knowledge to more tacit, procedural knowledge and skills. Not only does this process influence what students are able to do given a task, but it also influences their experiences and identity work around such tasks, in this case writing (Chi et al., 1989). The process of self-assessment also contributes to students’ sense of self-efficacy and conditional knowledge as they engage in reflecting on their own learning, and improvement of their own work. However, it is important to note that student self-assessment is more effective when combined with teacher feedback, especially in domains where students lack expertise (Logan, 2015; Panadero et al., 2016).

Self-assessment, self-efficacy, and revision

The original Flower-Hayes (1981) model of the composing process focused on three cognitive processes in writing—planning, translating, and revision–-and discussed them within the context of how an individual writer responds to the task environment, all those factors influencing the writing task, and the writer’s long term memory, including the knowledge of the topic, audience, and stored writing plans. Over fifteen years later, in “A New Framework for Understanding Cognition and Affect in Writing” (Hayes, 1996), Hayes reorganized his model to include a social component in the task environment to acknowledge that writing is “a communicative act that requires a social context and a medium” (p. 5). Further, within the individual component of his model, he added motivation/affect under which he lists goals, predispositions, beliefs and attitudes, and cost–benefit analyses because “motivation and affect play central roles in writing processes” (p. 5). He specifically links positive and negative dispositions toward writing to self-assessment and self-efficacy, citing Dweck (1986) and Palmquist and Young (1992).

Hayes’ (2012) new framework also posits an evaluation function responsible for the detection and diagnosis of text problems during revision. He further postulates that to understand revision, it is necessary for writers to draw upon a control structure or task schema that enables them to access a “package of knowledge” that includes: “(i) A goal: to improve the text; (ii) An expected set of activities to perform; (iii) Attentional subgoals; (iv) Templates and criteria for quality; and (v) Strategies for fixing specific text problems” (p. 17). The addition of the control level to Hayes’ composing model indicates that motivation, self-assessment, detection and diagnosis, planning and goal setting, reflection, and writing task schemas all play an important role in students’ self-efficacy as writers. Hayes points out that students who believe writing is a gift rather than a craft one can work at and improve have higher levels of writing anxiety and lower self-assessments of their ability as writers.

In light of Hayes’ new framework, we hypothesize that engaging students in activities that prompt them to detect and diagnose areas for revision, plan and set goals for making both local and, more importantly, global changes (Hayes, 1996), and to reflect upon and assess their growth after revising will enhance their self-efficacy as writers and potentially impact their writing outcomes.

Teacher impacts on self-efficacy in writing

Studies have indicated that teachers can play an important role in developing student self-efficacy in writing. Corkett et al. (2011) found that teachers’ perceptions of students’ self-efficacy in writing are highly correlated with their students’ actual writing performance– indicating that teachers enact different instructional practices based on their perceptions of how prepared their students are for tackling different writing assignments. Their study also found that students’ perceptions of their own abilities are not predictive of their actual abilities, indicating that students still need specific instructional supports to develop their own perceptions of how they can improve their writing.

The nature of how teachers structure a writing task can also impact how certain students develop their self-efficacy in writing. In a study of gifted elementary school children, the treatment group that received formative feedback as they learned and practiced specific writing skills (e.g., topic sentences) and created assigned written products (e.g., a paragraph), better learned these skills and were more proficient at producing certain written products than the comparison group (Schunk & Swartz, 1993). However, goal setting and teacher feedback did not improve student self-efficacy with students with learning disabilities (LD) (Sawyer et al., 1992). It is conjectured that students with LD tend to overestimate their abilities, as is true for students with general low writing abilities, further necessitating classroom interventions or processes that will help students recognize areas of improvement in their writing and how to improve such skills.

Teachers’ own self-efficacy can also be impacted by teacher professional development (Locke et al., 2013) which provides them with more effective and “transformative” ways of teaching writing that can lead to improved student learning and student self-efficacy in writing. However, Locke and colleagues also indicate that teachers’ self-efficacy is moderated by the type of writing their students produce in their classrooms. This feedback loop of student data, teacher interpretation, and reflection on next steps demonstrates the importance of developing both teacher and student self-efficacy in writing.

In sum, studies on teacher self-efficacy and how it interacts with student self-efficacy demonstrate the influence the former has on the latter. Though self-efficacy is often an individual activity, when it comes to writing, input from a teacher influences how well students will approach their own writing tasks. Moreover, teacher self-efficacy beliefs also influence how positive and/or confident teachers themselves feel about teaching writing to students, which again impacts how positive students approach these tasks (Troia & Graham, 2016).

Contributing factors to self-efficacy in writing

Beyond teachers, other factors that may impact students’ self-efficacy in writing are their motivation, their prior knowledge around the topic they are writing about, and the conditions under which they are being asked to write. Students who are highly motivated to receive feedback (e.g., help-seeking) on their performance are more likely to do well on writing tasks, indicating that students who are more motivated to improve will produce better writing (Williams & Takaku, 2011). Similarly, students are also motivated if they have past success with writing, have been exposed to positive writing habits, have been praised by their peers for their writing, and have associated positive feelings with their writing (Bruning & Kauffman, 2016). Students who study for mastery and depth have higher self-efficacy than students who only have surface-level knowledge and have lower self-efficacy because of their motivations and success with past learning experiences (Prat-Sala & Redford, 2010). Students also benefit from seeing how other people write and approach writing and self-calibrating to these examples (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2007). Moreover, the feedback that they receive around their writing, from both teachers and peers, can impact their self-efficacy. Students tend to internalize the feedback they receive and associate this feedback with whether they are good or bad at writing, along with the emotions that come with these self-assessments (e.g., guilt, confusion, anxiety, or fear) (Smith, 2010). Hidi and Boscolo (2006), for instance, noted that emotions (negative or positive) can serve as a mediating variable between self-efficacy and writing quality. In other words, feeling good while writing is its own reward, and encourages one to see oneself as a good writer and to engage in more writing.

Finally, the context or situation in which students are asked to write can also impact their perceptions of their own self-efficacy. Elementary school students tend to have higher self-efficacy in writing than middle and high school students, and these effects are also stronger for female students across grade levels that report having lower anxiety when it comes to writing tasks (Pajares et al., 2007). As expectations increase, the more potential there is for students to feel challenged by these expectations.

Contributions of this study

This study explores the relationship between self-assessment, planning and goal setting, and reflection on self-efficacy in student writing by having students use a revision planner as part of their writing process during a strategy-based reading and writing intervention. The revision planner encourages students to analyze what they did well on a selected piece of writing, with feedback from an experienced reader, quite similar to the mastery experiences Pajares and colleagues (2007) identified as promoting student self-efficacy in writing. Additionally, beyond identifying the strengths and needs of their writing assignment, students also plan and create achievable goals before revising their essay as well as reflect upon how well they met those goals after revising (McMillan & Hearn, 2008). Like a rubric (Andrade et al., 2010), a planner can serve as a tool to support students in revising and improving their work. Unlike a rubric, a planner focuses students’ attention on actionable steps that they can take to reach specific goals that they can set for themselves—based upon what they have learned throughout the intervention—to help them manage their revision process and revise their writing successfully. We are particularly interested in the impact that goal setting, supported by the use of a planner, might have on student writing performance, self-assessment, and self-efficacy in writing.

Method

Study context

This sequential mixed methods study took place during the last year of a five-year grant awarded to our institution to validate the effectiveness of a cognitive-strategies approach to writing instruction in partnership with Norwalk La Mirada Unified School District (NLMUSD) and three other school districts in California. The previous four years were spent on designing and conducting a randomized control trial involving the districts’ grade 7 to 12 grade students. During the year we conducted this study (2017–2018), NLMUSD exclusively requested that grade 6 teachers be provided with the same professional development in an effort to institutionalize and scale-up the intervention (Olson et al., 2019). NLMUSD is a large, urban school district that serves 80% Hispanic students, 8% White students, 7% Asian students, 3% African American students, and 2% are Other Ethnicities. Additionally, 61% of their students are English Only students, 17% of their students are English Learners, 16% are Reclassified Fluent English Proficient students, and 6% of their students are Initially English Proficient. About 75% of the district’s students participate in the Federal Reduced Price Lunch program. Participating teachers and students were recruited from NLMUSD specifically as the other three school districts institutionalized the intervention in other ways. Teachers in this grade 6 cohort all received the same intervention as previous cohorts of teachers. However, in addition to testing the efficacy of the teacher intervention with all teachers and students, we were also interested in testing a student intervention, that we hypothesized would have implications on their self-efficacy as writers. The focus of our student intervention, thus, was at a different level and with a different grade level than that of the larger RCT study. We collected quantitative data on students first, then followed by a qualitative component to understand what may have contributed to students’ self-efficacy while revising.

Teacher and student participants

This cohort of participating grade 6 teachers consisted of 13 teachers. Each teacher had one focal class. Approximately 401 students were part of this cohort. All teachers participated in our professional development intervention. The student intervention component differed between randomly assigned groups. Of these students, 131 students were in the treatment group and 83 were in the comparison group, as one teacher declined to participate in the random assignment, representing an 8% attrition rate of teachers (leaving 12 teachers to be randomized). Across both groups, 52% of the students were female, 76% were Hispanic, and 62% of the students are Redesignated English Learners, a percentage that is much higher than the overall district demographics, since focal classes with higher percentages of ELs and RFEPs for all teachers’ classes (treatment and comparison) were selected for the study. The Self-Efficacy in Writing (SEW) means at baseline for both groups were not statistically different (mtx = 3.61; mc = 3.56).

Professional development intervention for teachers

In order to distinguish between the grade 7 to 12 study and this sub study of grade 6 teachers, we are providing a description of the professional development program since all teachers in this study were in the same PD and were trained together. We will subsequently explain what the “treatment” teachers in our self-efficacy intervention did that was above and beyond the PD all teachers attended to account for differences in student outcomes. Participating teachers attended 46 h of professional development throughout the school year, consisting of six full-day meetings and five after-school meetings.

The professional development intervention is informed by cognitive, sociocognitive, and sociocultural theory. In their cognitive process theory of writing, Flower and Hayes (1981) posit that writing is best understood “as a set of distinct thinking processes which writers orchestrate and organize during the act of composing” (p. 375), including planning, organizing, goal setting, translating, monitoring, reviewing, evaluating, and revising. They liken these processes to a “writer’s tool kit” (p. 385), which is not constrained by any fixed order or series of stages.

In describing the difficulty of composing written texts, Flower and Hayes (1980) aptly conceptualized writers as simultaneously juggling “a number of demands being made on conscious attention” (p. 32). While all learners face similar cognitive, linguistic, communicative, contextual, and textual constraints when learning to write (Frederiksen & Dominic, 1981), the difficulties younger, inexperienced, and underprepared students face are magnified. For these students, juggling constraints can cause cognitive overload. For example, ELs are often cognitively overloaded, especially in mainstreamed classrooms where they are held to the same performance standards as native English speakers (Short & Fitzsimmons, 2007).

Graham (2018) has pointed out that “available cognitive models mostly ignore cultural, social, political, and historical influences on writing development” (p. 272). He asserts that writing is “inherently a social activity, situated within a specific context” (p. 273). This view echoes Langer (1991) who, drawing on Vygotsky (1986), suggests that literacy is the ability to think and reason like a literate person within a particular society. In other words, literacy is culture specific and meaning is socially constructed. From a sociocognitive perspective, teachers should pay more attention to the social purposes to which literacy skills are applied, and should go beyond delivering lessons on content to impart strategies for thinking necessary to complete literacy tasks, first with guidance and, ultimately, independently.

Finally, sociocultural theory views meaning as being “negotiated at the intersection of individuals, culture, and activity” (Englert et al., 2006, p. 208). Three tenets of sociocultural theory are applicable to the intervention (Adapted from Englert et al., 2006): (1) Cognitive apprenticeships: in which novices learn literate behaviors through the repeated modeling of more mature, experienced adults or peers to provide access to strategies and tools demonstrated by successful readers and writers (Vygotsky, 1986). (2) Procedural facilitators and tools: where teachers are most effective when they lead cognitive development in advance of what students can accomplish alone by presenting challenging material along with procedural and facilitative tools to help readers and writers address those cognitive challenges. (3) Community of practice: the establishment of communities of practice in which teachers actively encourage students to collaborate and provide ongoing opportunities and thoughtful activities that invite students to engage in shared inquiry.

The central core of the PD is the use of cognitive strategies to support all students in reading and writing about complex text. Cognitive strategies are conceptual tools and processes that can help students become more meta-cognitive about their work. The following are the cognitive strategies introduced in the PD:

Planning and Goal Setting, Tapping Prior Knowledge, Asking Questions and Making Predictions, Constructing the Gist, Monitoring, Revising Meaning, Reflecting and Relating, and Evaluating. Some sub-components are: Visualizing, Making Connections, Summarizing, Adopting an Alignment, Forming Interpretations, Analyzing Author’s Craft, and Clarifying Understanding (Olson, 2011, p. 23)

The primary intent of the professional development is to provide teachers with lessons and materials to introduce the cognitive strategies to students toward the intended goal of improving students’ analytical essays about either fiction or non-fiction texts.

Teachers also learned specific writing strategies to help students revise their writing. To avoid “teaching to the test,” teachers use a different text, but similar in topic as the text used for the writing assessment as a training tool in order to model how to revise the pre-test into a multiple draft essay. Throughout a series of mini-lessons, students are taught a variety of skills through examining a mentor text/essay based on the training text. Students first read the training text using the aforementioned 15 cognitive strategies. Then, they are given a writing prompt similar to the one they used on the writing assessment. This writing prompt is dissected by having students fill out a Do/What Chart which instructs students to circle all of the verbs (Do) and underline all of the task words (What) in the prompt and transfer the verbs and tasks words onto a T-chart to help them understand what they are being asked to do (for example, “Select one important theme and create a theme statement.”) Then, students are given a mentor text/essay addressing the prompt they just dissected. This mentor text/essay is analyzed for the moves the writer makes, particularly in how he or she constructed the introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion.

When working with the introduction, students are taught the HoT S-C Team (Hook/TAG/Story-Conflict/Thesis) acronym. The students are to identify that a writer often starts with an engaging hook that could be a quote, question or statement to make people think, fact, or even anecdote; then identifies the title-author-genre (TAG) of the text being written about to set the context for writing; adds purposeful summary of the story or conflict, and includes a thesis (claim).

Each component of the mentor text is color-coded using yellow (for summary sentences), green (for textual evidence), and blue (for student commentary) to help the students understand that a balance of purposeful summary, textual evidence, and commentary is important when constructing an analytical essay. Additionally, students are also taught about grammar brushstrokes (Noden, 2011) such as adding adjectives out of order, appositives, or using active verbs and are encouraged to revise some of their sentences with these brushstrokes to enhance sentence variety.

One of the essential activities in this intervention is to have teachers help students revise their on-demand writing samples into a more polished analytical essay, after these writing samples have been read and commented on by trained readers. It is during this part of the main study that our team decided to conduct the sub study on student self-efficacy. Given that all teachers experienced and received the same professional development and, in turn, taught the same revision strategies to their students, the only difference that we tested rested solely on asking the treatment students to use the Pre-Test Essay Revision Planner and Revised Pre-Test Reflection form. This self-assessment, planning and goal setting, and reflection strategy is aligned to Hayes’ (2012) control level of writing, which involves student self-efficacy. A more detailed explanation of this new intervention strategy follows.

Student intervention: pre-test revision planner and revised pre-test reflection form

In prior studies of our intervention, we have routinely asked teachers to analyze their students’ pre-tests as a formative assessment and to fill out their own reflection planner regarding their students’ strengths and areas needing growth as a tool to help with instruction. After reading about how much student self-efficacy influences writing outcomes (Bruning et al., 2013), we wondered if having students participate in assessing their own strengths and areas for improvement as writers and fill out a reflection similar to the one their teachers created would lead to better writing outcomes. With the consent of teachers participating in the intervention, we randomized the teachers’ classes into two groups. The comparison group received instruction from their teacher on how to revise their pre-test essays and were provided with comments from a trained reader. The treatment group not only received instruction from the teacher and comments from a trained reader, but also conducted a self-assessment of their work and filled out the Pre-Test Essay Revision Planner and Revised Pre-Test Reflection form to describe their process and assess the quality of their product after revising. Since all the students, treatment and comparison groups, participated in the same intervention and were taught the same strategies, this study tests the impact of the Pre-Test Essay Revision Planner and Revised Pre-Test Reflection form on students’ self-efficacy and writing quality. To promote treatment fidelity, all teachers, treatment and comparison, were required to submit their students’ revised pre-tests to the intervention developers in order to receive their stipend for participating in the year-long study. Treatment teachers were also required to submit the Pre-Test Essay Revision Planner planner.

To elaborate, the process we took treatment students involved two steps. The first part of the Pre-Test Essay Revision Planner (see Appendix 1) asked students to self-assess what they did effectively as writers on their essay and what they might have struggled with on the writing task. They were then asked to decide on goals for revisions in bulleted form, weighing suggestions by trained readers who commented on their papers. These were action steps the student proposed to take when revising his or her essay. After they have completed their revision, students reflected on what changes they made, what they were most proud of, and what their teacher did to help them reach their revision goals using the Revised Pre-Test Reflection form. In the comparison condition, students revised their pretests, but without the use of a planner, keeping everything else equal.

Sample student pre-test, revision planner, and revised pre-test

This section illustrates the multi-faceted components of the intervention. We start by examining a student’s pre-test with commentary from an experienced reader, then her revision planner, next her revised pre-test, and finally her self-assessment and reflection and consider how these components affect a student’s self-efficacy in writing.

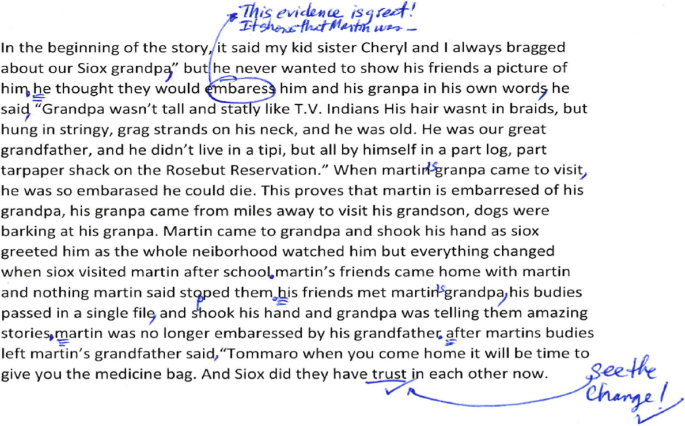

The prompt the student responded to was an analysis of Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve’s short story “The Medicine Bag” for its theme as exhibited through the evolving relationship between the narrator and his great-grandfather as he visits him unexpectedly and the symbolism behind the gift he leaves the narrator prior to his passing (Fig. 1):

The student’s attempt at the on-demand essay consists almost exclusively of summary, indicating that her command of analytical writing is still developing. The student starts the analysis with “In the beginning of the story…” followed by a long summary of the plot and puts forth the claim “this proves that Martin is embaress [sic] of his grandpa…” While this is not a theme statement it does indicate the writer’s understanding of the text. The trained reader also notes the writer’s recognition that the character changes over time and encourages her to focus on the author’s message or lesson when she revises (Fig. 2).

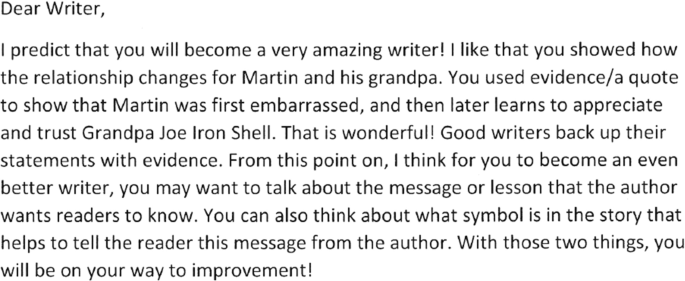

The comments the student received from the trained reader focused revision on connecting commentary to textual evidence, developing a theme statement, and the role symbols play in the story. These types of comments are quite typical of the responses many students in this study received from our trained readers. After teachers received these comments and reviewed them, they passed these papers back to their students and treatment teachers had students fill out the Pre-Test Essay Revision Planner (see Fig. 3). We conjecture that this opportunity to self-assess may contribute to her persistence through the revision process better than her comparison peers who may only rely on given feedback, but no reflection nor goal setting (Bruning & Kauffman, 2016).

In her Pre-Test Essay Revision Planner, the student first focused on the strengths of her essay—what she did well. Then she addressed what she struggled with or didn’t do as well in her essay. Next, she set a goal to revise the introduction, by including a hook and TAG which indicates Title, Author, and Genre, and especially to “talk more about the message.” Much of what the student plans to do is quite specific to revising the introduction; revising an introduction and knowing what is expected can help students produce more focused papers that are organized with a clear direction in terms of analysis. Below is her revision of the writing assessment (Fig. 4):

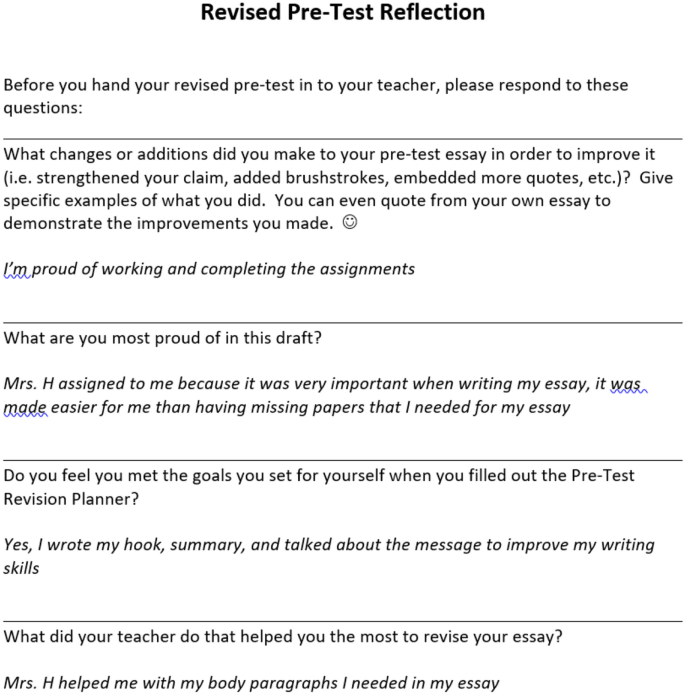

The student’s revision is a noticeable improvement over her original pre-test. The revision has included a hook (e.g., an anecdote around traditions), attempts a theme statement (e.g., the importance of traditions), addresses the changing the relationship between the narrator and his grand-father, and also focuses on the medicine bag as a symbol. Notice how the student meets her revision goals, but also takes up the suggestion to focus on symbolism. The moves the student makes from pre-test to revision are akin to a student that makes a transition from knowledge-telling (e.g., summary) to knowledge-transformation (e.g., commentary) in their writing (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987). For example, in the students’ pre-test, she summarized how Martin exaggerates about his grandfather but did not explain how this exaggeration relates to his embarrassment. In the revision of this paper, the student explains, in detail, why Martin was embarrassed by his grandfather and why he felt compelled to make him seem more “glamorous” and larger than life. Moreover, the reflection on the revisions she made (below) demonstrates ownership over her revision process, with her teacher’s help (Fig. 5):

The student recognizes the changes she made from her pre-test to the revised version, particularly the inclusion of a message or theme statement and the improvements she made. She also emphasized how helpful her teacher was in helping her revise her body paragraphs, which was a goal that was not particularly emphasized on her revision planner, but proved to be a writing move that was successfully executed. The student exhibited a strong sense of self-efficacy. Note, her expression of pride in working on and completing the assignment).

Data collection and measures

Self-efficacy for writing scale

To examine student growth in self-efficacy, particularly in writing, we adapted a pre-existing self-efficacy in writing measure called the Self-Efficacy for Writing Scale (SEWS), reliably measured by another research team (Bruning et al., 2013), by adding additional questions regarding revision practices. After cleaning the data for complete entries at pre and post-survey, our sample size consisted of 214 students who had completely filled out a pre and post-survey. The SEW survey had 22 Likert-scale questions on a scale from 1 to 5 in terms of how much they agree with each statement. To further analyze the SEW survey, but to also simplify the analytical process, we also conducted a factor analysis to reduce the number of components and created four composites, for specific areas of self-efficacy, as a result. The four composites used in our analysis, the questions that pertained to each one, and the factor loadings after applying orthogonal varimax rotations (Abdi, 2003) are in Table 1 below:

Ideation groups questions regarding students’ ideas and content in their essays together; Syntax pertains to students’ focus on grammar, spelling, and paragraph formation; Volition pertains to students’ abilities to follow-through with their assignment and complete it; and Revision questions pertain to students’ abilities to revise their paper for specific skills.

Academic writing assessment

In order to test the impact of an increase in self-efficacy in writing on students’ analytical writing, we used students’ scores on the Academic Writing Assessment, a writing assessment created for our intervention, that is administered to students prior to the intervention and after revision of the pre-test. Two prompts (one on “The Medicine Bag” and one on “Ribbons”) were created regarding two texts where the main character’s relationship with a grandparent changes throughout the story. The students stated a claim or theme statement about relationships and use textual evidence to support this theme. To control for prompt effects half of the students wrote to one of these prompts at pre-test and wrote to the other prompt at post-test, and vice versa.

Approximately twenty papers were randomly selected for scoring per teacher. Assessments were scored in a double blind process over four hours where the scorer neither knew if the paper they were scoring was written by a treatment or comparison student nor whether they were scoring a pre-test or post-test. Each paper was read twice and given a score from a range of 1 to 6, with possible score points from 2 to 12. If the two readers differed by more than two points (e.g., a 2 and 4) then a third, more experienced reader also gave the paper a score. If the third reader’s score matches either the first or the second reader, the third reader’s score was added to the score it matched. If the third reader’s score fell in between the first and second reader’s score, the third reader’s score was kept and the average of the first and second reader’s score was added to the kept score. All papers were scored in such a manner during a scoring event held over four hours. Raters agreed within a score point or better for 95% of the papers; 5% required a third reading, and 49% of the papers had exact agreements between the two scorers.

Pre-test essay revision planner and revised pre-test reflection form

To reiterate, the form asked students to self-assess, plan and goal set during revision, and reflect on the process after finishing their revisions. The reflection side of the planner was inspired by Daniel et al. (2015) who found that students who wrote a cover letter to their instructors detailing the changes they made to a revised paper, based on instructor feedback, submitted higher-quality revised papers than their control peers. The theory of change behind this planner is that it encourages students to identify problem areas, set goals, and remind them of these goals as they revise their pretest, encouraging them to accomplish these goals (see Daniel et al., 2015).

Student interviews

A sub-set of students from both the comparison and treatment classrooms were selected for interview purposes. Without knowing students’ AWA scores, teachers were asked to nominate one developing writer and one more proficient writer for the interviews. Selected students were provided with their pre-test, their revised pre-test, and their post-test; treatment students also were provided with their Pre-Test Essay Revision Planner and Revised Pre-Test Reflection form. Students were interviewed in the same room, but sat far away enough from each other so that ambient noise from the other interview being conducted would not be captured. Students were asked a series of open-ended questions (see Appendix 2) about their identities as writers (e.g., From a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rate yourself as a writer?); about their revision process; and what helped them to revise their papers/to meet their goals.

Research procedures

Randomly selected teachers chose one focal class with which to conduct these research activities:

-

1.

Students in the selected classes were asked to take two timed on-demand writing assessments–one at the beginning of the school year and one at the end of the school year. These essays were scored during a double-blind session based on the Academic Writing Assessment (AWA) rubric that we created and validated in other studies (see Olson et al., 2017).

-

2.

The students also took two self-efficacy in writing (SEW) surveys, one at the beginning of the school year and one at the end of the school year.

-

3.

In between the two SEW surveys students’ teachers either were randomly assigned to have students reflect on their writing or not to reflect on their writing using the Pre-Test Essay Revision Planner and Revised Pre-Test Reflection form while revising their pretests.

-

4.

Afterwards, two students from each class were randomly interviewed on their writing process with questions that focused on their identity as a writer and what helped them as writers.

Data analysis

To analyze growth on our SEW measure, we ran t-tests to measure change from pre to post on each of our aforementioned components from our factor analysis (ideation, syntax, volition, and revision). We then also ran t-tests to measure change from pre to post on the AWA differentiating between the treatment and comparison groups in order to test the impact of self-efficacy in writing on timed on-demand writing tasks.

Students’ revision-planners and post-revision reflections were analyzed for the types of goals students created for themselves by looking at idea units. Student interviews were transcribed by the first and second author, divided into idea units, and coded for students’ revision processes and what strategies/resources might have assisted them in doing so. Codes were independently generated and then verified between the two coders until they were agreed upon (Miles & Huberman, 2008).

Results

Students with higher self-efficacy have better writing outcomes

When analyzing AWA scores, treatment students grew 1.90 points and the control students grew 1.33 points from pre to posttest. Both gains were statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating that the intervention had a positive impact on all participating students. However, differences in differences confirm that the treatment students had statistically significant greater gains than their control peers (△ = 0.57; p < 0.001).

Students’ reflections have positive impact on students’ self-efficacy in writing

At post-survey, the treatment SEW mean increased to 3.63 (p < 0.76) and the control mean decreased to 3.47 (p < 0.37). Differences in differences analysis revealed a slight statistical difference (p < 0.10; △ = 0.11). The alpha level reported for the SEW items was 0.90.

Table 2 displays the pre to post means for the four composites from our factor analysis of the SEW questions: Ideation (idea formation); Syntax (grammar); Volition (persistence), and Revision (revision for clarity and content).

Based on these results, treatment students grew more than their comparison peers in the area of Revision strategies by 0.21 points; whereas, they both decreased in their Volition scores. However, the treatment students had less of a decline (e.g., -0.05 rather than -0.28 points). It is possible that both treatment and comparison students, who are in sixth grade, do not yet feel confident in producing high quality-writing samples during on-demand timed conditions; yet both groups managed to do so.

Students cite teacher instruction as most helpful in revising their writing

Qualitative analysis of the student interviews revealed that treatment students perceived the planner as being helpful as it provided them with a road map and check list as to what to focus on in the revision of their pre-test essay. For example, one student explained that her revision planner helped her “to know what I was supposed to do to my new revision.” She was able to reference her planner as she wrote and notice things that she forgot to include, which she then went back to add into the appropriate part of her essay. Additionally, for this student, filling out the planner was a process scaffolded by the written feedback she had received from the aforementioned trained reader as well as from her classroom teacher. It was the feedback and concrete suggestions she received, such as the reader comment that told her “I should add an author name, TAG line, and a title” and her teacher who suggested she “put it [my writing] in paragraphs and organize them,” that she used to set goals for herself in terms of what changes to make in order to improve her pretest. These comments were reflected in the list that the student wrote for herself on her revision planner, which included notes like “add a title,” “add a hook,” “organize paragraphs,” and “add the author’s name.” In her interview, when comparing her drafts, she pointed out these details like the hook and title she added as proof that she had made successful revisions. Other students who found the planner helpful reported similar experiences, such as working on the planner as a class with the guidance of the teacher, focusing on the different elements of essay writing they had learned about through the school year such as the parts of a strong introduction. One student even wrote down “reread the writing prompt” in her planner as part of her list of things to do, highlighting the use of her planner as a list of actionable steps for revising.

Moreover, it was particularly important that teachers taught or modeled specific strategies to address the revisions students needed to make, like showing them examples of how essay writers organize information into multiple paragraphs. One student said, for instance, that one thing that really helped her in her revisions was all the review and practice that her teacher had them do over the course of the year. These included reviewing specific aspects of “what to do in an essay, like how to start it and how to end it and when we should put the body paragraphs.” The fact that her teacher returned to these concepts more than once helped her remember what to consider when it came time to revise her pretest.

Many students felt their teachers modeled helpful strategies to develop a claim and to write a strong introduction. Writing hooks and including important information about the texts they were analyzing like the title, author, and genre, for example, came up frequently. However, students did not provide the same evidence for the development of their body paragraphs, particularly when it came down to providing their own commentary around the evidence they used to back up their claims. Although one student noted that she added details about the story’s characters to her draft to make it better and another stated that she learned that she had to add her own thoughts or opinions into her summary in order to make it a proper essay, there was little mention of specific things to consider or of tying these details or opinions to specific arguments or evidence presented in their papers.

Both treatment and comparison students credited their teachers’ instruction as being most helpful in revising their essay. Some students went so far as to state that before participating in the intervention this year, they had only a vague idea of what an essay was, let alone what parts it was supposed to have. For instance, one student explained that what helped him most in revising was “my teacher” who “was telling us… teaching us basically about theme, the hook, the introduction and the conclusion.” However, treatment students used more self-efficacious words such as the use of the first-person pronoun, “I,” “plans,” “knew what to do,” and were quick to point out exactly which parts of their papers were improved. In contrast, comparison students more often used the more global second-person pronoun, “we” or third-person pronoun “she/he [the teacher,” “told us what to do,” and “lesson” when describing their revision process. Additionally, they were less specific about where and how they improved their papers, explaining that they had improved their papers because they “got an order” or added “more details.” The distinction between the use of pronouns is also a hallmark of self-efficacious individuals who centralize the locus of control around writing to what they can do, rather than external sources such as an authority figure or more knowledgeable other. Though feedback in any form is useful. Individuals who take an active role in their own writing also exhibit better reflective skills (Shantz & Latham, 2011), particularly on the items we found on our SEW survey (Parisi, 1994).

Discussion

Our study confirms that the higher a student’s self-efficacy in writing, the higher quality of writing will be produced, even on timed on-demand writing tasks. We also confirmed that teachers’ instructional practices have an impact on students’ self-efficacy in writing (Corkett et al., 2011; Schunk & Swartz, 1993). Most importantly, our findings suggest that a planned revision process that includes student self-assessment, planning and goal setting, and reflection (McMillan & Hearn, 2008) positively impacts self-efficacy. Prompting students to take ownership of their own learning, enabling them to assess their strengths and areas for improvement, providing direction in terms of accomplishing complicated writing tasks, and encouraging them to reflect upon their writing performance are what Hayes’ (2012) advocated for in his new framework. Students have a goal to improve their pre-test and outline the revision activities that need to be completed, while their teachers provide them with the success criteria and strategies to complete these goals.

Moreover, the process of revising their pre-tests provides students with the opportunities to develop positive affect towards the revision process as they are given opportunities to: (i) reflect on what they did well on their pre-tests and capitalize on their existing knowledge; (ii) observe, learn, and analyze successful writing moves during the revision tutorial by comparing non-examples with examples; (iii) receive constructive written feedback from trained readers on how to revise their pre-test; and (iv) experience and learn explicit writing skills that reduce anxiety as they deconstruct what a prompt is asking for and/or how to provide effective commentary on textual evidence (Bruning & Kauffman, 2016; Pajares et al., 2007).

The field is looking for interventions that can metaphorically move the needle for students from almost empty to full, particularly in literacy development. In the case of our study, the planner moved the needle for our treatment students because it gave students concrete direction on how to improve their pre-tests and this, in turn, impacted their performance on the post-tests. Our intervention contributes to the knowledge base on the impact reflection and goal setting can have on student writing. All students can benefit from explicit self-regulation and strategy development instruction (Graham & Harris, 1989; Harris et al., 2006), particularly if they support student reflection, goal setting, and self-monitoring strategies. Similar to Blake et al.’s recommendations (2016), embedding micro-goals that students can feel are accessible, feasible, and accomplishable can help students feel more in control of the revision process. Having a revision planner makes this process more scaffolded, explicit, and visible to students.

This work also demonstrates the importance of teacher instruction on student writing. As both treatment and comparison students cited their teachers’ instructions as most influential, these findings provide further support that writing instruction requires a teacher who is confident and well-equipped to provide students with guidance on how they can improve their writing. Engaging students in assessing their own strengths and areas for growth and then reflecting on their progress can enhance students’ motivation and commitment. However, a student may not be able to fully meet the goals they have set without explicit (or scaffolded) instruction by the teacher and classroom practice. Such instruction can contribute not only to a student’s self-confidence but also to their sense of competence. Hence, these findings provide further support that students’ self-efficacy is connected to teacher expertise.

Limitations

Though this study has promising results, it is not without limitations. We acknowledge that the sample was small and any findings need to be validated with a larger sample size; however, the fact that statistical significance was achieved demonstrates the potential of the revision planner in helping students develop stronger self-efficacy in writing skills. Additionally, more qualitative studies to triangulate the usefulness of the revision planner are needed to understand how the planner directly translated to results on the post-test.

Implications

Implications from this study demonstrate how important it is to provide students with the skills, strategies, and opportunity to engage in self-assessment and revision processes. This development of their declarative (what), procedural (how), and conditional (why) knowledge of how to compose text-based analytical essays and the pivotal role self-assessment can play in successful revision that can cultivate independent, self-efficacious learners who have the confidence and competence to succeed as analytical writers in secondary school and beyond.

References

Abdi, H. (2003). Multivariate Analysis. In M. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, & T. Futing (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Social Sciences Research Methods. SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Andrade, H. L., Du, Y., & Mycek, K. (2010). Rubric-referenced self-assessment and middle school students’ writing. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 17(2), 199–214.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Macmillan.

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 307–377). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Barzilai, S., Zohar, A. R., & Mor-Hagani, S. (2018). Promoting integration of multiple texts: A review of instructional approaches and practices. Educational Psychology Review, 30, 973–999.

Batalova, J., Fix, M., & Murray, J. (2005). English language learner adolescents: Demographics and literacy achievements. Report to the Center for Applied Linguistics. Migration Policy Institute.

Batalova, J., & McHugh, M. (2010). Top languages spoken by English anguage learners nationally and by state. Migration Policy Institute.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Biancarosa, G., & Snow, C. (2004). Reading next—A vision for action and research in middle and high school literacy: A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York (2nd ed.). Alliance for Excellent Education.

Blake, M. F., MacArthur, S. M., Philippakos, Z. A., & Sancak-Marusa, I. (2016). Self-regulated strategy instruction in developmental writing courses: How to help basic writers become independent writers. Teaching English in the Two Year College, 44(2), 158–175.

Bong, M. (2006). Asking the right question: How confident are you that you could successfully perform these tasks? In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 287–303). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Bruning, R., Dempsey, M., Kauffman, D., McKim, C., & Zumbrunn, S. (2013). Examining dimensions of Self-efficacy for writing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(1), 25–38.

Bruning, R., & Kauffman, D. (2016). Self-efficacy beliefs and motivation in writing development. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (p. 160–173). The Guilford Press.

Capps, R., Fix, M., Murray, J., Ost, J., Passel, J., & Herwantoro, S. (2005). The new demography of America’s schools: Immigration and the No Child Left Behind Act. Urban Institute.

Chi, M. T., Bassok, M., Lewis, M. W., Reimann, P., & Glaser, R. (1989). Self-explanations: How students study and use examples in learning to solve problems. Cognitive Science, 13, 145–182. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1302_1

Corkett, J., Hatt, B., & Benevides, T. (2011). Student and teacher self-efficacy and the connection to reading and writing. Canadian Journal of Education, 34(1), 65–98.

Daniel, F., Gaze, C., & Braasch, J. L. G. (2015). Writing covers letters that address instructor feedback improves final papers in a research methods course. Teaching of Psychology, 42, 64–68.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10

Englert, C. S., Mariage, T. V., & Dunsmore, L. (2006). Tenets of sociocultural theory in writing instruction research. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 208–221). Guilford Press.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1980). The dynamics of composing: Making plans and juggling constraints. In L. Gregg & E. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive processes in writing (pp. 31–50). Erlbaum.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition and Communication, 32, 365–387. https://doi.org/10.2307/356600

Fredericksen, C. H., & Dominic, J. F. (1981). Introduction: Perspectives on the activity of writing. In C. H. Fredericksen & J. F. Dominic (Eds.), Writing: The nature, development and teaching of written communication (Vol. 2, pp. 1–20). Erlbaum.

Graham, S. (2018). A writer(s)-within-community model of writing. In C. Bazerman, A. Applebee, V. W. Berninger, D. Brandt, S. Graham, J. V.Jeffery, et al. (Eds.), The lifespan development of writing (pp. 258–325). Urbana, IL: NCTE. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2018.1481406

Graham, S., Daley, S., Aitken, A., Harris, K., & Robinson, K. (2018). Do writing motivational beliefs predict middle school students’ writing performance? Journal of Research in Reading, 41(4), 642–656.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (1989). Improving learning disabled students’ skills at composing essays: Self-instructional strategy training. Exceptional Children, 56, 201–214.

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellence in Education (Commissioned by the Carnegie Corp. of New York).

Harris, K. R., Graham, S., & Mason, L. (2006). Improving the writing, knowledge, and motivation of struggling young writers: Effects of self-regulated strategy development with and without peer support. American Educational Research Journal, 43(2), 295–340.

Hernandez, D. J., Denton, N. A., & McCartney, S. E. (2008). Children in immigrant families: Looking to America’s future. Social Policy Report, 22, 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2379-3988.2008.tb00056.x

Hayes, J. R. (1996). A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing. In C. M. Levy & S. Ransdell (Eds.), The science of writing: Theories, methods, individual differences, and applications (pp. 1–27). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Hayes, J. R. (2012). Modeling and remodeling writing. Written Communication, 29(3), 369–388.

Hidi, S., & Boscolo, P. (2006). Motivation and writing. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of Writing Research (pp. 144–157). The Guilford Press.

Kiuhara, S. A., Graham, S., & Hawken, L. S. (2009). Teaching writing to high school students: A national survey. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(1), 136–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013097

Langer, J. A. (1991). Literacy and schooling: A sociocognitive perspective. In E. H. Hiebert (Ed.), Literacy for a diverse society: Perspectives, practices, and policies (pp. 10–27). Teachers College Press.

Locke, T., Whitehead, D., & Dix, S. (2013). The impact of “Writing Project” professional development on teachers’ self-efficacy as writers and teachers of writing. English in Australia, 48(2), 55–69.

Logan, B. (2015). Reviewing the value of self-assessments: Do they matter in the classroom? Research in Higher Education Journal, 29, 1–11.

McMillan, J. H., & Hearn, J. (2008). Student self-assessment: The key to stronger student motivation and higher achievement. Educational Horizons, 87(1), 40–49.

Menken, K., & Kleyn, T. (2009). The difficult road for long-term English learners. Educational Leadership, 66, 7. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational_leadership/apr09/vol166/num07/TheThe_Difficult_Road_for_Long_Term_English_Learners.aspx

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES). (2012). Writing 2011: National Assessment of Education Progress at grades 8 and 12. Author.

National Commission on Writing. (2004). Writing: A ticket to work... or a ticket out: A survey of business leaders. Retrieved February 20, 2016, from http://www.collegeboard.com/prod_downloads/writingcom/writing-ticket-to-work.pdf

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State SchoolOfficers. (2010). Common Core State Standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Washington, DC: Authors.

Noden, H. (2011). Image grammar: Teaching grammar as part of the writing process (2nd ed.). Heinemann.

Olsen, L. (2010). Reparable Harm: Fulfilling the unkept promise of educational opportunity for California’s long-term English learners. Retrieved from http://www.californianstogether.org/long-term-english-learners/.

Olson, C. B. (2011). The reading/writing connection: Strategies for teaching and learning in the secondary classroom (3rd ed.). Pearson Inc.

Olson, C. B., Kim, J. S., Scarcella, R., Kramer, J., Pearson, M., van Dyk, D. A., Collins, P., & Land, R. E. (2012). Enhancing the interpretive reading and analytical writing of mainstreamed english learners in secondary school: Results from a randomized field trial using a cognitive strategies approach. American Educational Research Journal, 49(2), 323–355.

Olson, C. B., Matuchniak, T., Chung, H. Q., Stumpf, R. A., & Farkas, G. (2017). Reducing achievement gaps in academic writing for Latino secondary students and English learners. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000095

Olson, C. B., Woodworth, K., Arshan, N., Black, R., Chung, H. Q., Aoust, D., & Stowell, C. L. (2020). The pathway to academic success: Scaling up a text-based analytical writing intervention for Latinos and English Learners in secondary school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(4), 701–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000387

Pajares, F., Johnson, M. J., & Usher, E. L. (2007). Sources of writing self-efficacy beliefs of elementary, middle, and high school students. Research in the Teaching of English, 42, 104–120.

Palmquist, M., & Young, R. (1992). The notion of giftedness and student expectations about writing. Written Communication, 9(1), 137–168.

Panadero, E., Brown, G. T., & Strijbos, J. W. (2016). The future of student self-assessment: A review of known unknowns and potential directions. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 803–830.

Parisi, H. A. (1994). Involvement and self-awareness for the basic writer: Graphically conceptualizing the writing project. Journal of Basic Writing, 13(2), 33–45.

Perin, D., Lauterbach, J., Raufman, J., & Kalamkarian, H. S. (2017). Text-based writing of low-skilled postsecondary students: Relation to comprehension, self-efficacy, and teacher judgments. Reading and Writing, 30, 887–915.

Prat-Sala, M., & Redford, P. (2010). The interplay between motivation, self-efficacy, andapproaches to studying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 283–305. http://dx.doi.org.ezp.sub.su.se/https://doi.org/10.1348/000709909X480563

Sanders-Reio, J., Alexander, P. A., Reio, T. G., Jr., & Newman, I. (2014). Do students’ beliefs about writing relate to their writing self-efficacy, apprehension, and performance? Learning and Instruction, 33, 1–11.

Sawyer, R. J., Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (1992). Direct teaching, strategy instruction, and strategy instruction with explicit self-regulation: Effects on the composition skills and self-efficacy of students with learning disabilities. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 340–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.340

Schunk, D., & Swartz, C. (1993). Writing strategy instruction with gifted students: Effects of goals and feedback on self-efficacy and skills. Roeper Review, 15, 225–230.

Schunk, D., & Zimmerman, B. (2007). Influencing children’s self-efficacy and self-regulation of reading and writing through modeling. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 23(1), 7–25.

Shantz, A., & Latham, G. (2011). The effect of primed goals on employee performance: Implications for human resource management. Human Resources Management, 50, 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20418

Short, D., & Fitzsimmons, S. (2007). Double the work: Challenges and solutions to acquiring language and academic literacy for adolescent English language learners-A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York. Alliance for Excellent Education.

Smith, C. (2010). Diving in deeper: Bringing basic writers’ thinking to the surface. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53(8), 668–676.

Tierney, R. J., & Pearson, P. D. (1983). Toward a composing model of reading. Language Arts, 60, 568–580.

Troia, G., & Graham, S. (2016). Common Core writing and language standards and aligned state assessments: A national survey of teacher beliefs and attitudes. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 29(9), 1719–1743.

U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Educational Sciences, National Center for Education tatistics. (2017). The condition of education: English language learners 2014–15. Author.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2016). The condition of education 2016 (NCES 2016–144), English language learners in public schools. Author.

Valdés, G. (2001). Learning and not learning English: Latino students in American schools. Teachers College Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language. MIT Press.

Williams, J. D., & Takaku, S. (2011). Help seeking, self-efficacy, and writing performance among college students. Journal of Writing Research, 3(1), 1–18.

Worden, D. L. (2009). Finding process in product: Prewriting and revision in timed essay responses. Assessing Writing, 14, 157–177.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Pretest Essay Revision Planner and Revised Pretest Reflection.

Pre-Test essay revision planner

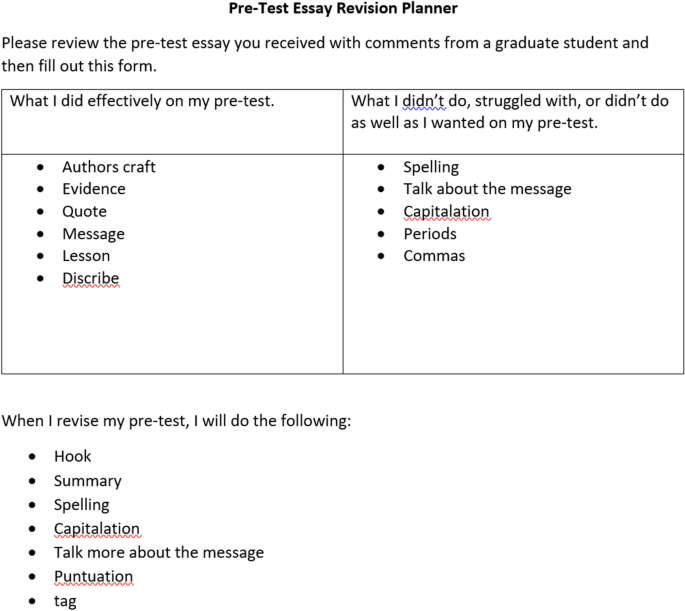

Please review the pre-test essay you received with comments from a UCI graduate student and then fill out this form.

What I did effectively on my pre-test | What I didn’t do, struggled with, or didn’t do as well as I wanted to on my pre-test |

When I revise my pre-test, I will do the following:

Revised pre-test reflection

Before you hand your revised pre-test in to your teacher, please respond to these questions:

What changes or additions did you make to your pre-test essay in order to improve it (i.e. strengthened your claim, added brushstrokes, embedded more quotes, etc.)? Give specific examples of what you did. You can even quote from your own essay to demonstrate the improvements you made.

What are you most proud of in this draft?

Do you feel you met the goals you set for yourself when you filled out the Pre-Test Revision Planner?

What did your teacher do that helped you the most to revise your essay?

Appendix 2

Post-Test Semi-Structured Interview Protocol (Students).

-

1.

In what ways has your view of your ability as a writer changed since the beginning of the year? (Feel free to rank yourself on a scale of 1 to 10)

-

2.

What do you feel most confident about in writing? What are you most proud of accomplishing this year as a writer?

Revision:

-

3.

How did you feel when you read the comments you received on your pre-test essay from the UCI Graduate Student?

-

4.

Can you explain the revisions you made to your pre-test? What goals did you have in re-writing your paper? What did you do to change your essay and why did you change it the way that you did?

-

5.

What helped you the most to revise your paper? (Tx only: To what degree id you use this planner when you revised? How helpful was it?)

-

6.

What do you feel are the strengths of your revised essay? Do you feel like you met your goals? (Tx only: Show list on Revision Planner) Why or Why not?

-

7.

What do you feel you struggled with in revising your essay?

Post-Test:

(Have students physically look at pre-test and post-test)

-

8.

As you compare your pre-test and post-test, do you notice any improvement? If so, in which areas do you think you improved the most from the pre-test to the post-test?

-

9.

What strategies did you learn and use in writing your essay (and where/when did you first learn these strategies)?

-

10.

What did the teacher do over the course of the year that you feel was most helpful to you developing as a writer?

-

11.

In what areas do you think your writing still has the most room for improvement?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, H.Q., Chen, V. & Olson, C.B. The impact of self-assessment, planning and goal setting, and reflection before and after revision on student self-efficacy and writing performance. Read Writ 34, 1885–1913 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10186-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10186-x