Abstract

The purpose of this article is to illustrate the growing limitations of the current methods of calculating earnings, particularly when earnings is a negative number. Earnings, presumably the most important output of a financial reporting system, is not a singular metric. It is obtained by subtracting numerous expense line items from revenues, both of which are calculated after applying a diverse, and often inconsistent, set of accounting conventions. Despite this apparent deficiency, earnings could be informative of recurring profits, if revenues are measured correctly and expenses are traced to revenues. However, both principles are increasingly violated for the cohorts of firms listed in the last 30 years, which now constitute over 80% of the set of listed firms. Revenues of recent cohorts do not capture many events that create recurring cash flows. Their operating expenses are dominated by intangible outlays that are unmatched to current revenues. As a result, newer cohorts’ profits and profit margins, especially when negative, offer little to inform future profits. Given that revenue and expense recognition rules are unlikely to change anytime soon, the current developments raise a question: Should the reporting of the summary measure of earnings be voluntary instead of mandatory?

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

When the stock market crashed in October 1929, so did public confidence in the US markets.Footnote 1 Congress held hearings to identify the cause of the crash and to search for solutions. Based on its findings, Congress passed the Securities Act (SEA) of 1933 in the peak year of the Great Depression. The act requires companies offering securities for sale to the public to “tell the truth about their business, the securities they are selling, and the risks involved in investing in those securities.” An integral part of this truth-telling exercise is to provide an audited financial report, inclusive of an income statement, on at least an annual basis.Footnote 2

Academics and practitioners have since debated the purpose of the income statement and its importance relative to the balance sheet (Basu and Waymire 2010). Debate also is ongoing about the meaning and measurement of earnings, which is the bottom-line, summary metric of the income statement. For example, Black (1980) argues that earnings should be a measure of value (adjusted for price-to-earnings ratio), not of changes in value. In contrast, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and some academics, arguably questionably, interpret Hick’s concept of personal income as the amount that a firm can pay out as dividends while leaving itself equally well off at the end of a period as it was at the beginning (Jameson 2005; Bromwich et al. 2005). This idea, consistent with the clean surplus assumption, more likely demonstrates the changes in value than the levels of value.

Dichev (2008) argues that a manager’s aim of securing revenues greater than costs, embodied in the income statement and earnings, is congruent with how firms create value. A positive earnings number would represent good news for shareholders, and a negative number would indicate bad news. A money-losing business would show expenses exceeding revenues. A reported loss, when also indicative of future losses, would imply a bad business for shareholders. Supporting this idea, Alchian (1950) argues that, in an impersonal market system, positive profits are the sole criterion for the selection of successful and surviving firms, while firms that suffer losses disappear. Graham et al. (2005) survey chief finance officers and analysts and find that earnings is the single most important output of financial statements. In the past, standard setters considered the income statement and earnings to be the primary focus of financial reporting [FASB Concepts Statement No. l (paragraph 43)].Footnote 3

Given the importance of earnings, much research has been conducted on the quality of earnings (Dechow et al. 2010). Yet no straightforward way exists to calculate earnings. The purpose of this article is to illustrate the growing limitations of the current methods of determining earnings, along with the resultant decreasing relevance of earnings, particularly when earnings is a negative number. To illustrate the point, I provide data on matching with revenues for cost of goods sold (COGS) and selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses—the two dominant operating costs—by cohorts of listed firms. I show that SG&A, inclusive of intangible investments, has become the dominant operating cost for newer firms, but its matching with revenues has diminished. Without matching, measured profits and profit margins become meaningless summary measures (Dichev 2008). This trend cannot be ignored, because cohorts listed in the last 30 years now constitute over 80% of the set of listed firms. Because revenue recognition and intangibles capitalization rules are unlikely to change soon, I conclude with a consideration of whether firms should be allowed to report Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) earnings on a voluntary basis, instead of it being mandatory (Beaulieu 2014).

This paper complements Gu et al. (2022), who use an innovative measure to identify firms that report losses because of the GAAP requirement to immediately expense inhouse intangible investments. Those GAAP-loss firms would report profits had they capitalized inhouse intangible investments and then expensed them over their useful lives, similar to capital expenditures. Gu et al. (2022) find that after the accounting bias for intangibles expensing is unraveled, the earnings of GAAP-loss firms become as informative as earnings of profitable firms. Furthermore, GAAP-loss firms subsequently outperform other loss firms and even profitable firms in value creation from intangible investments. The authors caution financial statement users to consider operational differences between GAAP-loss and other loss-making firms in the evaluation of losses.

2 Accounting conventions in preparing the income statement

Earnings is obtained by subtracting expense line items from revenues, both of which are calculated using different principles and accounting conventions.Footnote 4 Revenue recognition requires the fulfilment of two conditions: an objective determination of the value of goods and services that have been delivered and customer payments being probable. These conditions, however well intended, cause the first point of departure for revenues from numerous events that managers and shareholders consider value creating. For example, for a long time, Apple could not recognize any revenues upon selling and delivering an iPhone.Footnote 5 That is, the company that became the most valuable in the world, having created the “product of the century,” could not recognize revenues even after conceiving of that product, selling it, and having collected customer payments.Footnote 6 While that deficiency has been fixed with the new revenue recognition rules, numerous other events that could create a recurring stream of cash flows are still not recognized as revenues, such as the signing of an exclusive partnership with a tech giant, a patent approval, approval of a blockbuster drug by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a social influencer’s endorsement of a company’s product, and a social media company signing up a million new subscribers. None is recognized as revenues, because no delivery occurred. While this limitation applies to all companies, it is especially important for modern technology companies, which build a probable future stream of cash flows through a series of serendipitous events that increase the value and marketability of their ideas, not through investments in inventory or property, plant, and equipment (PP&E). The delivery criterion is based on a sound principle of resolution of uncertainty and applies to all businesses. Yet it increasingly causes an important departure of earnings from what investors consider to be value creating.Footnote 7

Expenses are calculated using numerous, inconsistent conventions.Footnote 8 Most costs associated with the procurement and production of physical goods are initially capitalized and presented in an inventory account. Inventory is then diminished via a COGS account when goods are delivered to customers. COGS is thus reported in the same period as its associated revenues and is highly matched to current revenues. COGS contributes 60–90% of total costs for brick-and-mortar firms such as Walmart and Ford. Thus, for a traditional brick-and-mortar company, profits is calculated after deducting operating costs that are highly matched to revenues.

A similar concept is applied to investments in PP&E. Purchase, delivery, and installation costs are initially capitalized in the PP&E account and then retired through a depreciation expense account over the expected period of use of PP&E. Unlike COGS, which is traced to revenues, depreciation expense is calculated mechanically, like ratable retirement over five years. Yet depreciation expense is expected to match the periods of PP&E’s benefits and thus, approximately, to revenues.

Another important core operating expense is SG&A. Numerous operating costs that cannot be capitalized in the inventory account or can be reported as cost of sales are reported in the SG&A account. Those costs include items such as head office expenses, sales commissions, warehouse rents, executive compensation, and delivery costs. Some costs, such as sales commissions and sales promotions, are recognized at the same time as the associated revenues and are highly matched to revenues. Others, such as head office expenses, do not easily adjust with ups and downs in sales and are less matched to revenues (Anderson et al. 2003).

More important, over the last 40 years or so, SG&A has increasingly included an emerging class of outlays: inhouse investments in intangibles. Those outlays include research and development (R&D), process improvement, information technology, software development, advertisement, organizational strategy, acquisition of customers, brand building, and hiring and training personnel. Except in certain industries, such as software development, oil and gas, and radio and recording, most inhouse intangible outlays are expensed as incurred. To the extent that SG&A represents investments in expectation of future benefits, it would be unmatched to current revenues.

Stock options, a principal way of paying workers in the knowledge economy, follow an altogether different convention. The Black-Scholes formula, used to calculate the value of stock options, is based on historical as well forward-looking information, but, more important, does not equal cash paid, a principle that applies to most other expenses. That value is then recognized as expense ratably over the options’ vesting period or immediately upon cliff vesting. The actual compensation received by employees, through exercise of stock options and sale of stocks, occurs only after the vesting period, when the stock price has gone up. Thus, stock option expense would likely be recognized in a period different than when the company’s fortune improves and its stock price increases.

Certain expenses, such as restructuring charges and those leading to contingent liabilities, result from current events but are based on estimates and judgment about future payouts. Other expenses, such as goodwill impairments, often pertain to events that occurred in past periods (Li and Sloan 2017). Interest expense is recognized during the period of loan outstanding and incorporates amortization of the bond premium and discount. Tax expense is related to profits, not revenues.

In sum, how net income is calculated has at least three deficiencies: (1) revenues often do not incorporate effects of events that could create recurring cash flows, (2) different line items of the expense statement are recognized using different principles and conventions, and (3) many expenses do not match with contemporaneous revenues.

A bridge built using parts that followed different engineering conventions, safety standards, and measurement systems, and with a design that ignored relevant information such as local weather and soil conditions, would likely be unstable. Conceptually, an income statement is no different than that bridge.

3 Prior literature on growing deficiencies of the income statement

It is not a new idea that the income statement is built using inconsistent principles and reports earnings that would be less meaningful than what the SEA (1933) originally intended. Ball and Brown (1968, p. 160) state: “Because accounting lacks an all-embracing theoretical framework, dissimilarities in practices have evolved. As a consequence, net income is an aggregate of components which are not homogeneous. It is thus alleged to be a ‘meaningless’ figure, not unlike the difference between twenty-seven tables and eight chairs.” Ball and Brown (1968) cite Canning (1929, p. 98): “What is set out as a measure of net income can never be supposed to be a fact in any sense at all except that it is the figure that results when the accountant has finished applying the procedures which he adopts.”

Despite these pessimistic predictions about the usefulness of earnings, Ball and Brown (1968) find that net income corresponds with contemporaneous stock returns. Profitable companies have positive returns on average, and loss-making companies have negative returns. Long and short portfolios formed with perfect foresight of profits and losses, respectively, earn significant returns. Loss is economically meaningful, as it is associated with real actions such as employee layoffs (Pinnuck and Lillis 2007) and shareholders’ exercise of the abandonment option (Hayn 1995). In addition, earnings is more predictive of cash flows than cash flows are (Finger 1994; Barth et al. 2001). Accruals, which differentiate earnings from cash flows, mitigate the timing differences between economic events and their cash flows, making earnings more informative of firm performance. As a result, working capital accruals are negatively associated with contemporaneous cash flows (Dechow 1994; Dechow et al. 1998).

More recent studies point to declining usefulness of earnings. Lev and Zarowin (1999) show that the value relevance of earnings (measured by the R-squared of regression between contemporaneous stock returns and levels and changes of net income) has declined over time. Srivastava (2014) shows that declining relevance is related to progressively lower relevance of successive cohorts of listed firms. After 2008, hedged portfolios formed based on high and low earnings-to-price ratio (long and short positions, respectively) no longer earn positive results, on average.Footnote 9 Nallareddy et al. (2020) show that earnings is less predictive of future cash flows than cash flows themselves are.Footnote 10 Bushman et al. (2016) document a decline in the magnitude of negative association between working capital accruals and contemporaneous cash flows. Green et al. (2022) show that this decline is related to inadequate capitalization of intangible investments. Gu et al. (2022) find that losses, to the extent they are due to immediate expensing of intangibles (GAAP loss firms), do not mean losses in the traditional sense. Contrary to expectations, GAAP loss firms survive over long periods, increase hiring, create valuable patents, and provide positive returns to shareholders.

4 Decline in matching of operating expenses

I examine one reason that earnings, particularly losses, has lost its relevance since Ball and Brown (1968). I build on arguments offered in prior literature (e.g., Lev and Zarowin 1999; Dichev and Tang 2008; Srivastava 2014), while offering new insights. Dichev and Tang (2008) argue that, without matching, net income is not a useful measure for valuation. For example, consider a biotechnology startup that has only one large expense: research and development outlays. With little or no revenues, it would report large losses. That company invests in R&D today with the hope of earning future revenues after the drug is developed and approved by FDA and marketed over its patent period. Almost every business operates on this principle, advancing costs in expectation of benefits (Fisher 1930; Dichev 2008). Firms invest in new factories, products, markets, brands, employees, business segments, warehouses, and inventory, anticipating that the present value of future revenues would exceed the current investments. Without comparing current investments with future revenues, a manager cannot determine the cost-benefit considerations that go into investment decisions. Similarly, an investor cannot figure out the recurring profit potential from reported earnings if expenses are not matched to revenues.

Dichev and Tang (2008) show a significant decline in matching over time. Srivastava (2014) extends Dichev and Tang (2008) by dividing firms into listing cohorts. I follow Srivastava (2014) by calling the first year in which a firm’s data are available in Compustat the “listing year.”Footnote 11 All of the firms with a listing year before 1960 are classified as “pre-1960s.” All other firms are divided into listing cohorts based on the decade in which they were listed. Thus, I divide all companies into seven groups: pre-1960s and cohorts for the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s.

Following Dichev and Tang (2008), I estimate the following regression on an annual cross-sectional basis for each group for each year:

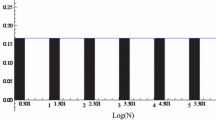

I calculate total expenses by subtracting net income (Compustat NI) from revenues (Compustat SALES).Footnote 12 I scale all of the variables by average total assets. Matching is measured by the regression coefficient on contemporaneous expenses (β3), which represents the contemporaneous revenue–expense correlation. I calculate matching for each of the seven groups by averaging their matching calculated on an annual basis. Figure 1 shows that matching for the pre-1960s, 1960s, and 1970s groups is approximately 1.0, indicating excellent matching. Each successive cohort shows lower matching. Matching for cohorts listed in the twenty-first century is noteworthy. It is only 0.25 and 0.10, respectively, for the 2000 and 2010 s cohorts, demonstrating that most of their expenses are unmatched to revenues.

Decline in revenue-expense matching, by listing cohorts. Description: The first year in which a firm’s asset data are available in Compustat is the listing year. All of the firms with a listing year before 1960 are classified as “pre-1960s.” All other firms are divided into listing cohorts based on the decade in which they were listed. Thus, I divide all companies into seven groups: pre-1960s and cohorts for the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. I calculate total expenses by subtracting net income (Compustat NI) from revenues (Compustat SALES). I estimate the following regression on an annual cross-sectional basis for each group for each year: \(\begin{aligned}Revenues_{i,t} &= \beta_{1,t}+\beta_{2,t} \times Total \ Expenses_{i,t-1}+\beta_{3,t} \times Total \ Expenses_{i,t} \\ &+ \beta_{4,t} \times Total \ Expenses_{i,t+1} + \varepsilon_{i,t}.\end{aligned}\) I scale all of the variables by average total assets. Matching is measured by the regression coefficient on the contemporaneous expenses (β3), which represents the contemporaneous revenue–expense correlation. I calculate matching for each of the seven groups by averaging their matching calculated on an annual basis and present it by group. Interpretation: The figure shows that matching for the pre-1960s, 1960s, and 1970s groups is approximately 1.0, indicating excellent matching. Each successive cohort shows lower matching. The low matching for the last two cohorts shows that most of their expenses are unmatched

I next measure matching of major components of expenses. I measure COGS and SG&A expenses by the Compustat data items COGS and XSGA, respectively, and call the remaining expenses “other expenses.” I measure the matching of COGS and SG&A expenses by β3 and β4, respectively, in the following equation, estimated first by group-year and then averaged over all years:

Panel A of Fig. 2 shows no decline in matching of COGS for successive cohorts. Thus, what is reported as cost of goods sold, cost of sales, or cost of revenues in the income statement is highly matched to revenues. Panel B shows that SG&A is also highly matched for traditional firms, represented by the pre-1960s, 1960s, and 1970s groups. Every successive cohort shows a progressive decline in SG&A matching. It is just 0.3 for the 1990s cohort and negative for the last two cohorts (depicted as zero in the figure). Thus, what is reported in SG&A for the firms listed in the last 30 years is practically unmatched to revenues.

Decline in matching of selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses but not of cost of goods sold (COGS), by listing cohorts. Description: The first year in which a firm’s asset data are available in Compustat is the listing year. All of the firms with a listing year before 1960 are classified as “pre-1960s.” All other firms are divided into listing cohorts based on the decade in which they were listed. Thus, I divide all companies into seven groups: pre-1960s and cohorts for the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. I calculate total expenses by subtracting net income (Compustat NI) from revenues (Compustat SALES). I measure COGS and SG&A expenses by the Compustat data items COGS and XSGA, respectively, and call the remaining expenses “other expenses.” I measure the matching of COGS and SG&A expenses by β3 and β4, respectively, in the following equation, estimated first by group-year and then averaged over all years: \(Revenues_{i,t}=\beta_{1}+\beta_{2} \times Total \ Expense_{i,t-1}+\beta_{3} \times COGS_{i,t}+\beta_{4}\times SG\&A_{i,t}+\beta_{5}\times Other \ Expenses_{i,t} + \beta_{6} \times Total \ Expenses_{i,t+1}+\varepsilon_{i,t}.\)

Panel A presents matching of COGS by groups, and Panel B presents matching of SG&A. Interpretation: Panel A shows no decline in matching of COGS for successive cohorts. Panel B shows that SG&A matching also remains high for traditional firms, represented by the pre-1960s, 1960s, and 1970s groups. Every successive cohort shows a progressive decline in SG&A matching, and SG&A matching is negative for the last two cohorts (depicted as zero in the figure). It is just 0.3 for the 1990s cohort

5 The growing importance of SG&A

I calculate the relative proportions of the three types of expenses for each firm-year by dividing them by that firm-year’s total expenses. I next examine those percentages by cohorts. To control for life-cycle stage, I consider only one year’s observation per firm in each cohort, from when that firm is three years old.Footnote 13 Cohort-wise cost patterns, after controlling for life-cycle stages, are represented in Fig. 3.

Changing cost pattern, by listing cohorts. Description: The first year in which a firm’s asset data are available in Compustat is the listing year. All of the firms with a listing year before 1960 are classified as “pre-1960s.” All other firms are divided into listing cohorts based on the decade in which they were listed. Thus, I divide all companies into seven groups: pre-1960s and cohorts for the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. I consider only one year’s observation per firm in each cohort—from when that firm is three years old—to control for firm life cycle. I calculate total expenses by subtracting net income (Compustat NI) from revenues (Compustat SALES). I measure COGS and SG&A expenses by the Compustat data items COGS and XSGA, respectively, and call the remaining expenses “other expenses.” The three costs are scaled by total expenses, and their averages are presented by groups in the figure. Interpretation: Each successive cohort shows a decrease in COGS and an increase in SG&A as a percentage of total expenses

COGS was the predominant cost for the pre-1960s, 1960s, and 1970s groups, being 68%, 68%, and 64%, respectively. SG&A was just 20%, 21%, and 24%, respectively, for the three groups. Each successive cohort has lower COGS, with the latest cohort reporting just 44%. More important, each cohort reports higher SG&A. By the time the 2010s cohort is reached, SG&A almost equals COGS. This trend is intuitive. Consider a modern business such as LinkedIn, Facebook, Moderna, or Google and contrast it with brick-and-mortar businesses such as Walmart and Ford. One would be hard-pressed to guess what items are reported in COGS for the former category of firms, while for the latter group the main cost items can be easily predicted as COGS. Table 1 lists prominent companies with the largest SG&A exceeding COGS from 2017 to 2020, indicating that SG&A being a dominant cost is a widespread phenomenon among modern firms. Figure 4 shows that the percentage of companies with SG&A greater than COGS increases with successive cohorts.

Percentage of firms with selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses exceeding cost of goods sold (COGS), by listing cohorts. Description: The first year in which a firm’s asset data are available in Compustat is the listing year. All of the firms with a listing year before 1960 are classified as “pre-1960s.” All other firms are divided into listing cohorts based on the decade in which they were listed. Thus, I divide all companies into seven groups: pre-1960s and cohorts for the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. I consider only one year’s observation per firm in each cohort—from when that firm is three years old—to control for firm life cycle. I present the percentage of firms with SG&A exceeding COGS groups in the figure. Interpretation: Each successive cohort has a greater percentage of firms with SG&A exceeding COGS

I next examine the cost trends for a sample of loss firms while controlling for the life-cycle stage. Figure 5 shows that among loss firms in the last three cohorts, SG&A exceeds COGS. This finding, when combined with the trend exhibited in Fig. 2, shows that loss firms listed in the last 30 years display SG&A as their dominant operating cost, but their SG&A is unmatched with revenues. Thus, their bottom-line numbers and profit margins are unlikely to be informative of recurring profitability. This problem is no different than what it would be for traditional firms if their investments in PP&E and inventory were immediately expensed instead of being capitalized.

Percentage of firms with selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses exceeding cost of goods sold (COGS) for loss firms, by listing cohorts. Description: The first year in which a firm’s asset data are available in Compustat is the listing year. All of the firms with a listing year before 1960 are classified as “pre-1960s.” All other firms are divided into listing cohorts based on the decade in which they were listed. Thus, I divide all companies into seven groups: pre-1960s and cohorts for the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. I consider only one year’s observation per firm in each cohort—from when that firm is three years old—to control for firm life cycle. I retain only loss firms. I present the percentage of firms with SG&A exceeding COGS groups in the figure. Interpretation: Each successive cohort has a greater percentage of firms with SG&A exceeding COGS. Among loss firms in the last three cohorts, on average, more firms have higher SG&A than COGS than have higher COGS than SG&A

The mismatch problem for traditional firms is solved by accrual accounting that scatters the investments in inventory and PP&E over the periods of their expected benefits, achieving a high degree of matching. Thus, their loss accurately represents a money-losing business with expenses exceeding revenues. For newer cohorts, losses lose their meaning because of a mismatch of their dominant costs—intangibles—even before considering the deficiencies in revenue recognition.

6 Importance of knowledge firms and newer listing cohorts

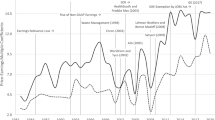

The deficiencies in the income statement would not matter if the firms listed in the last 30 years did not add significantly to the economy. Figure 6 shows that the composition of the set of listed firms keeps gravitating toward newer cohorts, no different than trends in any human population. Traditional firms, which represented a significant percentage of the listed population until 1980, now form a miniscule percentage of the set of listed firms. In 2020, the pre-1960s, 1960s, and 1970s cohorts provided just 4%, 4%, and 3%, respectively, to the set of listed firms (see Fig. 7). Thus, firms with COGS-dominated costs and a high degree of matching are just 11% of the listed population in 2020. In contrast, in 2020, the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s cohorts contributed as much as 17%, 17%, and 48%, respectively, to the set of listed firms (see Fig. 7).

Changing contribution of listing cohorts to the set of listed firms. Description: The first year in which a firm’s asset data are available in Compustat is the listing year. All of the firms with a listing year before 1960 are classified as “pre-1960s.” All other firms are divided into listing cohorts based on the decade in which they were listed. Thus, I divide all companies into seven groups: pre-1960s and cohorts for the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. I present the percentage contribution by numbers to the set of listed firms by year in the figure. Interpretation: The percentage contribution of each listing cohort to the set of listed firms decreases over time

Contribution of listing cohorts to the set of listed firms in 2020. Description: The first year in which a firm’s asset data are available in Compustat is the listing year. All of the firms with a listing year before 1960 are classified as “pre-1960s.” All other firms are divided into listing cohorts based on the decade in which they were listed. Thus, I divide all companies into seven groups: pre-1960s and cohorts for the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. I present the percentage contribution by numbers to the set of listed firms in 2020 in the figure. Interpretation: In 2020, over 80% of firms were listed after 1990

Stated differently, over 80% of the set of listed firms in 2020 is attributed to cohorts listed after 1990.Footnote 14 These firms are characterized by deficient revenue recognition and unmatched operating costs. Hence, one can interpret their earnings and losses in the spirit of Canning (1929, p. 98), in that they “can never be supposed to be a fact in any sense at all except that it is the figure that results when the accountant has finished applying the procedures which he adopts.” This explains the results of Gu et al. (2022), that losses for GAAP loss firms do not mean the same as losses for traditional firms.Footnote 15

7 Does irrelevance of earnings mean irrelevance of the income statement?

Barth et al. (2023) examine changes in value relevance of financial statement components over time and find that the value relevance of at least some income statement components has increased, not decreased. I discuss three components of the income statement that are highly value relevant: revenues, R&D expenses, and investment portion of SG&A.

Revenue has become highly value relevant for modern technology firms (Ertimur et al. 2003; Chandra and Ro 2008; Bowen et al. 2002). Many modern companies, such as LinkedIn and Facebook, offer an altogether novel class of services and create a new market for it. They typically have low variable costs and could earn winner-takes-all profits by dominating their market and taking advantage of the network effects. Achieving revenues is their best demonstration of the feasibility of their atypical business ideas. In addition, revenue growth is a reliable indicator of progress toward achieving viable market size and dominant market position. For such companies, revenues are highly value relevant, and investors often react more strongly to meeting or beating revenue targets than to achievement of earnings targets.Footnote 16

R&D is also highly value relevant because it is an essential tool for survival and growth for modern corporations and is not just a discretionary expense as considered in prior literature (Govindarajan et al. 2019; Barth et al. 2023). Furthermore, the investment portion of MainSG&A (that is, SG&A minus R&D and advertising) has become the largest category of firms’ operating investments, surpassing PP&E (Enache and Srivastava 2018). Treating it as an investment in the calculation of book value improves the returns from a value investment strategy (Lev and Srivastava 2022; Arnott et al. 2021; Iqbal et al. 2022).

In addition, investors pay attention to adjustments that firms make to provide non-GAAP earnings. Over 90% of Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 firms now report a non-GAAP performance measure, indicating either that a demand exists for such a metric or that firms consider a number other than the GAAP earnings number to be a better performance measure. Contracting is more likely based on a non-GAAP earnings metric than GAAP earnings. For example, firms frequently link chief executive officer compensation to a non-GAAP metric (Kyung et al. 2021). Many common debt covenants use some form of adjusted accounting earnings, such as earnings adjusted for interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (Li 2016).

In sum, highly value relevant line items are reported in income statements. But the relevance of the summary measure of GAAP earnings, particularly when it is negative, is becoming doubtful.

8 Should reporting GAAP earnings be made voluntary?

The relevance of GAAP earnings for modern technology firms is increasingly suspect. The nonrecognition of numerous value-creating events in revenues and the increasing mismatch between contemporaneous revenues and expenses are two principal reasons for this trend. FASB is unlikely to change revenue and expense recognition criteria soon, which raises the question of whether reporting a bottom-line number based on GAAP should be made an optional feature instead of being mandatory.

Mandatory reporting is supported by the arguments of consistency and comparability, but they must be weighed against the cost of preparation, audit, and user comprehension (Beaulieu 2014). Applying these considerations to data reported in this article raises the question: What is the point of reporting GAAP earnings for a biotechnology startup when no one cares about such earnings or compares them against earnings of a steel company or even another biotechnology company? If reporting GAAP earnings is made optional, only the companies that consider it valuable would make an effort to report that number. Another possibility is that firms could report what they consider the bottom-line metric, which is the best indicator of their recurring profits, while explaining how it is calculated, instead of first reporting a GAAP earnings number and then performing numerous adjustments to determine a non-GAAP number.Footnote 17

It is noteworthy that by reporting a bottom-line number, accountants implicitly convey their perspective on equity valuation (either levels of value, adjusted for P/E ratio, or of changes in value). The same accountants are reluctant to convey their assessments of the value of self-developed intangibles.

9 A blueprint for disclosures

Arguably, a focus on the current income statement structure and earnings distracts resources and attention away from more important and detailed disclosures that investors consider relevant. Govindarajan et al. (2018) suggest a structure for more value relevant disclosures. They argue that, first and foremost, companies should provide detailed information about their market and market prospects, broken into two main variables: total addressable market and targeted market share. Firms should report not just revenues but also the drivers behind the revenues, especially because modern companies’ operating activities often differ from their revenue-generating activities. For example, Facebook’s revenue-providing customers are the companies that pay for advertisements, not those who post personal information on Facebook’s website. How the activity and growth of Facebook’s subscribers drive the advertising revenues is highly relevant information for investors. An analyst following Facebook would thus look at variables such as the number of active users, their geographical distribution, their retention rates, the average amount of time they spend on the website, and the growth or decline in any of these factors.

As far as the costs are concerned, firms must provide a detailed description of outlays in three broad categories. First are outlays that support current operations, which could include soft expenses, such as customer acquisition, data breach and safety, regulatory fines, and product enhancement, or hard expenses, such as investments in hardware, servers, and cellphone towers. The economic life of hardware is increasingly lower than its physical life, given rapid technological obsolescence. Maintenance outlays should also include amounts spent on acquisitions required to maintain the firm’s competitive edge. Companies must also distinguish fixed from variable costs and detail the variable costs associated with a unit of activity. For example, Twitter provides “cost per ad engagement.”

Second are outlays that are expected to produce future benefits. Those outlays must be further divided into two more categories: those that improve current operations and those that have highly risky, lottery-like payoffs. More enhanced disclosures would include progress of future-oriented projects, how such projects are expected to affect (if at all) their current operations, the aggregate resources committed to the projects, and the likely launch dates.

Third are the so-called one-time or special items, which companies should identify and separate. They should be divided into two categories: those related to past investments that did not work out and those that are expected to require future payouts, such as expected layoffs and restructuring.

By making use of disclosures that follow this blueprint, a smart analyst could project a company’s future revenues, estimate the outlays required to sustain the firm’s business model, and calculate the present value of future cash flows. Analysts would then have the option to add, as they see fit, to that current operation valuation their own estimates of the option values of risky, moonshot projects.

10 Conclusion

Current revenue recognition rules ignore numerous events that are considered value creating by investors and managers of modern corporations. Expense recognition conventions increase the mismatch between revenues and expenses. Those two developments make GAAP earnings of modern companies, particularly losses, largely meaningless in their economic and valuation implications. Instead of GAAP earnings, investors seek more elaborate disclosures of items that would help them ascertain recurring profits. However, the way GAAP earnings is calculated is unlikely to change anytime soon. Hence, I recommend that companies be allowed to report a GAAP earnings number on a voluntary basis but that enhanced disclosures be mandated. Another possibility is to allow companies to report a bottom-line earnings number—one they consider value relevant—and to detail how it was calculated.

Notes

See “The Role of the SEC” at https://www.investor.gov/introduction-investing/investing-basics/role-sec#:~:text=The%20U.%20S.%20Securities%20and%20Exchange,Facilitate%20capital%20formation. Accessed on July 6, 2023.

See SEA (1933) at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/COMPS-1884/pdf/COMPS-1884.pdf.

Prior to the formation of the Securities and Exchange Commission and the accounting standard-setting bodies, financial reporting for US companies was not regulated at the federal level. Companies were free to choose their own reporting policies, although many listed companies reported income statement voluntarily (Archambault and Archambault 2010).

Arguably, standard setters no longer consider the income statement and earnings to be the primary focus of financial reporting (Dichev 2008; FASB 2010). Barker and Penman (2020, p. 323) criticize the conceptual framework (International Accounting Standards Board 2018): “The logic of this ‘balance-sheet approach’ is that (net) income is determined as a by-product of the recognition and measurement of (net) assets in the balance sheet. Accordingly, while much of the Framework is concerned with the definition, recognition, and measurement of (net) assets, it offers remarkably little conceptual guidance with respect to the income statement.”

Earnings also includes gains and losses, representing changes in values of marketable assets and liabilities. I do not discuss this deficiency in earnings.

This is evident from valuations of technology companies, despite their lack of physical assets.

Barker and Penman (2020) explain why conventions differ with respect to different expense items.

Data were obtained from Ken French’s data library, available at https://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/ftp/Portfolios_Formed_on_E-P_CSV.zip. Returns are negative for 2009, 2010, 2012, 2015, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020—that is, in eight out of 12 years from 2009 to 2020.

Ball and Nikolaev (2022) show that operating earnings beats operating cash flow in predicting operating cash flow. They point to deficiencies in bottom line earnings because it contains financing and investing cash flow items that never enter operating cash flows—for example, depreciation and amortization expenses, gains and losses on asset dispositions, impairments of intangible assets such as goodwill, amortization of premiums and discounts on long-term debt, a portion of equity method earnings, and non-cash stock-based compensation.

The Compustat listing year is a few years ahead of the listing year obtained from the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) database. I use the Compustat listing year to maintain consistency with the financial data from Compustat, similar to Srivastava (2014). Using the CRSP listing year merely shifts the cohort classification by a few years and does not affect the overall trends (results not tabulated).

This expense measurement includes numerous items that are unrelated to operations of the company, which again points to deficiencies in earnings.

Differences in percentages across cohorts could reflect differences in firms’ life-cycle stages, because newer cohorts are in earlier life-cycle stages, and younger firms typically spend a greater percentage of their costs on innovation and marketing than do older firms. A three-year criterion is used for parsimony. Results are robust to alternative cut-offs such as one year or five years. Nevertheless, this criterion would not control for life cycle if firm age at the time of initial public offering differs across cohorts.

This analysis assumes equal weighting of all observations, which is consistent with the general practice of research in financial accounting.

A large percentage of loss firms whose risky investments fail would never display profits. In that case, accounting losses could depict real losses.

Facebook’s stock lost $120 billion on July 26, 2018, and $232 billion on February 3, 2022. In both instances, the company met its earnings target but missed its revenue target.

This suggestion implies the reversal of Regulation G (Securities and Exchange Commission 2003).

References

Alchian, A.A. (1950). Uncertainty, evolution, and economic theory. Journal of Political Economy 58: 211–221.

Anderson, M., R. Banker, and S. Janakiraman. (2003). Are selling, general, and administrative costs “sticky”? Journal of Accounting Research 41: 47–63.

Archambault, J.J., and M. Archambault. (2010). Financial reporting in 1920: the case of industrial companies. The Accounting Historians Journal 37 (1): 53–90.

Arnott, R.D., C.R. Harvey, V. Kalesnik, and J.T. Linnainmaa. (2021). Reports of value’s death may be greatly exaggerated. Financial Analysts Journal 77 (1): 44–67.

Ball, R., and P. Brown. (1968). An empirical evaluation of accounting income numbers. Journal of Accounting Research 6: 159–178.

Ball, R., and V. V. Nikolaev. (2022). On earnings and cash flows as predictors of future cash flows. Journal of Accounting and Economics 73(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2021.101430.

Barker, R., and S. Penman. (2020). Moving the conceptual framework forward: accounting for uncertainty. Contemporary Accounting Research 37 (1): 322–357.

Barth, M.E., D.P. Cram, and K.K. Nelson. (2001). Accruals and the prediction of future cash flows. The Accounting Review 76 (1): 27–58.

Barth, M. E., K. Li, C. McClure. 2023. The evolution in value relevance of accounting information. The Accounting Review 98 (1): 1–28.

Basu, S., and G.B. Waymire. (2010). Sprouse’s what-you-may-call-its: fundamental insight or monumental mistake? Accounting Historians Journal 37 (1): 121–148.

Beaulieu, P. (2014). Voluntary income reporting. Accounting Horizons 28 (2): 277–295.

Black, F. (1980). The magic in earnings: economic earnings versus accounting earnings. Financial Analysts Journal 36 (6): 19–24.

Bowen, R.M., A.K. Davis, and S. Rajgopal. (2002). Determinants of revenue-reporting practices for internet firms. Contemporary Accounting Research 19 (4): 523–562.

Bromwich, M., R. Macve, and S. Sunder. (2005). FASB/IASB revisiting the concepts: a comment on Hicks and the concept of ‘income’ in the conceptual framework. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=59bc4499f0274202e8077ba28952b62733b0927c. Accessed 7 Jul 2023.

Bushman, R.M., A. Lerman, and X.F. Zhang. (2016). The changing landscape of accrual accounting. Journal of Accounting Research 54 (1): 41–78.

Canning, J.B. (1929). The economics of accountancy: a critical analysis of accounting theory. New York: The Ronald Press.

Chandra, U., and B.T. Ro. (2008). The role of revenue in firm valuation. Accounting Horizons 22 (2): 199–222.

Dechow, P.M. (1994). Accounting and economics: the role of accounting accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics 18: 3–42.

Dechow, P.M., W. Ge, and C. Schrand. (2010). Understanding earnings quality: a review of the proxies, their determinants, and their consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2–3): 344–401.

Dechow, P.M., S.P. Kothari, and R.L. Watts. (1998). The relation between earnings and cash flows. Journal of Accounting and Economics 25: 133–168.

Dichev, I.D. (2008). On the balance sheet–based model of financial reporting. Accounting Horizons 22 (4): 453–470.

Dichev, I., and V. Tang. (2008). Matching and the changing properties of accounting earnings over the last 40 years. The Accounting Review 83 (6): 1425–1460.

Enache, L., and A. Srivastava. (2018). Should intangible investments be reported separately or commingled with operating expenses? New evidence. Management Science 64 (7): 3446–3468.

Ertimur, Y., J. Livnat, and M. Martikainen. (2003). Differential market reactions to revenue and expense surprises. Review of Accounting Studies 8 (2–3): 185–211.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (2010). SFAC no. 8: conceptual framework for financial reporting. Norwalk, CT: FASB.

Finger, C.A. (1994). The ability of earnings to predict future earnings and cash flow. Journal of Accounting Research 32 (4): 210–223.

Fisher, I. (1930). The theory of interest. New York: Macmillan.

Govindarajan, V., S. Rajgopal, and A. Srivastava. (2018). A blueprint for digital companies’ financial reporting. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/08/a-blueprint-for-digital-companies-financial-reporting. Accessed 24 June 2023.

Govindarajan, V., S. Rajgopal, A. Srivastava, and L. Enache. (2019). It’s time to stop treating R&D as a discretionary expenditure. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/01/its-time-to-stop-treating-rd-as-a-discretionary-expenditure. Accessed 24 June 2023.

Graham, J.R., C.R. Harvey, and S. Rajgopal. (2005). The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 40: 3–73.

Green, J., H. Louis, and J. Sani. (2022). Intangible investments, scaling, and the trend in the accrual–cash flow association. Journal of Accounting Research 60 (4): 1551–1582.

Gu, F., B. Lev, and C. Zhu. (2023). All losses are not alike: real versus accounting-driven reported losses. Forthcoming, Review of Accounting Studies.

Hayn, C. (1995). The information content of losses. Journal of Accounting and Economics 20 (2): 125–153.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2018). Conceptual framework for financial reporting. London: IASB.

Iqbal, A., S. Rajgopal, A. Srivastava, and R. Zhao. (2022). Value of internally generated intangible capital. University of Calgary working paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3917998. Accessed 24 June 2023.

Jameson, J. (2005). FASB and IASB versus J. R. Hicks. Research in Accounting Regulation 18: 331–334.

Kyung, H., J. Ng, and G. Yang. (2021). Does the use of non-GAAP earnings in compensation contracts lead to excessive CEO compensation? Efficient contracting versus managerial power. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 48 (5–6): 841–868.

Lev, B., and A. Srivastava. (2022). Explaining the recent failure of value investing. Critical Finance Review 11 (2): 333–360.

Lev, B., and P. Zarowin. (1999). The boundaries of financial reporting and how to extend them. Journal of Accounting Research 37 (2): 353–385.

Li, N. (2016). Performance measures in earnings-based financial covenants in debt contracts. Journal of Accounting Research 54 (4): 1149–1186.

Li, K., and R.G. Sloan. (2017). Has goodwill accounting gone bad? Review of Accounting Studies 222: 964–1003.

Nallareddy, S., M. Sethuraman, and M. Venkatachalam. (2020). Changes in accrual properties and operating environment: implications for cash flow predictability. Journal of Accounting and Economics 69 (2–3): 1–23.

Pinnuck, M., and A. Lillis. (2007). Profits versus losses: does reporting an accounting loss act as a heuristic trigger to exercise the abandonment option and divest employees? The Accounting Review 82 (4): 1031–1053.

Securities and Exchange Commission. (2003). Final rule: conditions for use of non-GAAP financial measures. Release No. 33-8176, 34-47226, FR-65, FILE NO. S7-43-02. https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-8176.htm. Accessed 24 June 2023.

Srivastava, A. (2014). Why have measures of earnings quality changed over time? Journal of Accounting and Economics 57 (2–3): 196–217.

Acknowledgements

This article is related to my discussion of the paper “All Losses Are Not Alike: Real versus Accounting-Driven Reported Losses,” at the 2022 RAST conference. I gratefully acknowledge comments and helpful suggestions from Mark Anderson, Sudipta Basu, Phil Beaulieu, Patricia Dechow (Editor), and Ilia Dichev. I also thank the Canada Research Chairs program of The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Srivastava, A. Trivialization of the bottom line and losing relevance of losses. Rev Account Stud 28, 1190–1208 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-023-09794-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-023-09794-5