Abstract

The accounting process is complex and prone to interference from the various parties involved. Using middle managers, we examine one of the unknowns of this process. They are able to influence earnings long before top executives can, but their actions are virtually untraceable in consolidated financial statements. We gather survey data from 77 middle managers to shed light on their motivations, the extent of their earnings management, and the relevant limitations of the associated practices. Our results indicate that there is no uniform motivation that drives all of these managers equally. The spectrum of reported motivations includes meeting targets, smoothing earnings, and reducing future expectations. Despite this diversity, a large majority of the surveyed middle managers state that they manage earnings substantially but mostly downwards. To this end, they employ both accounting actions, such as adjustments to provisions, and real actions, such as transaction shifts. In the opinions of the middle managers in this sample, the factors that most limit their discretion are auditors and internal controls. The results also reveal the influence of superiors on middle managers’ practices throughout the accounting process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The objective of this study is to examine middle managers’ earnings management practices. A middle manager is one of the many parties involved in the complex multi-level accounting process. It is exceedingly difficult to align all individual interests—including those of middle managers—to create just and objective records. In this regard, the sheer numbers of individuals, opinions, goals, and motivations involved in accounting also increase its susceptibility to manipulation. One of the most common ways of influencing accounting is earnings management, which supposedly reduces earnings quality (Dechow et al. 2010) but may also relay private, value-relevant information (Subramanyam 1996).

Due to their importance, earnings management and, by association, earnings quality are widely researched topics. Especially top management (e.g., Bergstresser and Philippon 2006; Cheng et al. 2016; Dichev et al. 2013), auditors (e.g., Bartov et al. 2001; DeAngelo 1981; Teoh and Wong 1993), and analysts (e.g., Brown et al. 2015; Yu 2008) are the subjects of extensive research in this regard. Consequently, research focuses mostly on firms’ consolidated financial statements, while middle managers are largely overlooked (Beuselinck et al. 2019). However, a corporate group’s middle managers connect top management to lower management and staff members and thus are exposed to a tension field of diverging interests (Clinard 1983; Nonaka 1988). While lower management’s leverage on earnings is arguably rather small due to the incremental and case-based nature of their work,Footnote 1 middle managers are responsible for operating their respective subunits. To this end, they are authorized to exert the decision rights granted to them by top management (Abernethy et al. 2004) but are held individually accountable for achieving their objectives (Fauré and Rouleau 2011). Accordingly, they are required to report on the efficiency of their subunit’s use of organizational resources and ultimately the success of their units, which is routinely measured with earnings (Pfeffer 1981). In the process, they may follow their own agendas, which may not align with those of top executives and the company (Stewart 1979). Thus, we argue that they engage in earnings management to achieve their objectives. Depending on the level of freedom that they have to execute their job, middle managers are able to influence the amount of earnings management before the CEO and CFO seize control. This is especially noteworthy if not all cases of middle managers’ earnings management are coordinated with top management. In these instances, top executives’ earnings directives might be applied to the already-managed earnings. Specifically, Dichev et al. (2013) find that about 20% of companies’ top executives manage earnings by approximately 10%, which is in addition to the undisclosed earnings management of middle managers.

Although the effect of middle managers’ earnings management on the consolidated financial statements is potentially significant, only a few studies examine the earnings management practices of middle managers. In a field study, Merchant (1990) shows that profit centre managers manipulate short-term performance measures to meet financial targets. Chong and Wang (2019) and Guidry et al. (1999) also provide initial evidence that middle managers manage earnings. Specifically, Guidry et al. (1999) analyse archival data of a large conglomerate and show that business unit managers engage in earnings management to maximize their short-term bonuses. In an online survey, Chong and Wang (2019) find an increase in misreporting for higher degrees of decision rights moderated by managers’ responsibility rationalization. They show that business unit managers manage earnings to achieve their bonus targets. Beuselinck et al. (2019) offer insights into the drivers of earnings management and report on intra-organizational earnings management within multinational corporations. Cheng et al. (2016) specifically focus on real earnings management. Their archival results suggest a reduction in real earnings management through stronger internal governance. The present study complements the prior research and addresses middle managers directly to provide a broader picture of their earnings management practices.

Building on the research design of Dichev et al. (2013, 2016), our analysis addresses three complementary issues. First, we look into the various motivations of middle managers to engage in earnings management. Second, we explore the extent of middle managers’ earnings management. Third, we consider which factors limit middle managers’ discretion over earnings. Hence, we respond to the calls for research regarding the under-exploration of individual persons involved in earnings management (Lo 2008; Watts and Zimmerman 1990). To examine these issues, we gather survey data from 77 middle managers in German firms. Besides target beating, reducing future expectations, earnings smoothing, and superiors’ pressure represent important motives for approximately one-third of these middle managers. Overall, however, the motivations of the middle managers surveyed are diverse and not as singular as those of top management. Further, our results support our expectation that middle managers indeed conduct earnings management. Specifically, a large majority of the respondents confirm that they manage earnings, in an amount that averages 7.52% of the total earnings (6.01% for the whole sample). Managers further show an inclination to use real actions. Even though adjustments to provisions are the most common instrument for earnings management, followed by valuation adjustments, real actions in the form of transaction shifts are among the measures most often employed. We further document that, on average, the surveyed middle managers engage in earnings management every second year. In contrast to some of the previous literature (cf. Walker 2013), our results show that the managers of the present sample mostly manage earnings downwards. This finding is in line with the reported motives. Our data suggest that the factors that most limit the surveyed middle managers’ discretion are auditors, internal controls, and their superiors. Superiors thereby prove not only to initiate earnings management through their orders and pressure but also to restrict discretion.

The findings contribute to the accounting literature in the following ways. First, this study extends the existing literature by presenting a nuanced picture of middle managers’ earnings management practices. In doing so, the results also show differences from top management and indicate that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to understanding earnings management and to preventing detrimental manifestations, for example through targeted regulatory actions. In contrast to top management, the influence of middle managers on the overall quality of financial statements has passed largely unnoticed because top management is ultimately responsible for a company’s reported financial results and has significant discretion over the accrual process. Top management’s use of this discretion to manage earnings is well documented in the literature, with compensation and capital market concerns among the most prominent, but also debated, motives (Walker 2013). While both top and middle managers are essentially self-interested agents, the amount of wealth that they can acquire in the short term is substantially different. High performance bonuses and stock options may entice top managers to employ earnings management to reach their targets (Bergstresser and Philippon 2006). Bonuses for middle managers, however, are significantly smaller, making them more dependent on future income (Cheng et al. 2016; Clinard 1983). While Guidry et al. (1999) focus on bonus considerations to explain middle managers’ earnings management for a US sample, the present results, obtained from an environment that is not as capital market oriented, suggest that the middle managers surveyed pay little regard to bonus considerations when managing earnings.

The findings thus provide valuable insights into the concrete motivations of middle managers in a situation in which compensation is not among the main drivers. These motivations also reflect other differences from top management, such as middle managers’ longer employment horizon or their central role within the firm that requires them to execute top management’s specifications (Nonaka 1988). By examining the motivations in conjunction, we document which of these are the main drivers for the middle managers whom we survey, thereby extending the existing studies, which each concentrate on a limited number of motives (e.g., target beating in the study by Merchant 1990). The same is true for the boundaries of middle-management practices (e.g., governance in the study by Cheng et al. 2016). Due to their overall lower exposure to capital markets and their central position in the company, the stakeholders of middle management differ from those of top management, and so do their boundaries in some respects. Understanding the motives and limitations in this way helps to tailor the design of management control and incentive systems (Chen et al. 2020). To this end, it is also expedient to verify which motivations and limitations coincide with those of top management.

Second, to our knowledge, this is the first study to document the magnitude of earnings management for a sample of middle managers. Studies published thus far show that middle management engages in earnings management but not its potential extent, which is virtually unobservable to outsiders (Chong and Wang 2019; Guidry et al. 1999; Merchant 1990). In particular, information on subsidiaries’ and business units’ earnings management is lost through consolidation and is therefore not accessible when analysing only a corporate group’s financial statements. If it passes unnoticed by their superiors, middle managers’ earnings management could also subtly impede decision making and jeopardize performance measurement and incentives within the organization (Abernethy and Wallis 2019).

Further, the findings extend the ongoing discussion regarding different groups of managers’ preferences for earnings management practices. In particular, the literature on top management shows that, in line with their strategic role, CEOs prefer to use accrual earnings management while CFOs prefer real actions due to their monitoring role in financial reporting (Baker et al. 2019; Feng et al. 2011; Geiger and North 2006; Graham et al. 2005; Jiang et al. 2010). However, it is not clear how a group acts when it is not primarily responsible for strategy or financial reporting, is closer to operations, and is mainly interested in its respective unit’s results as previous studies on middle management focus on either accrual (Guidry et al. 1999) or real earnings management (Cheng et al 2016; Merchant 1990). The present study shows that the examined middle managers employ both accounting and real actions and lists the specific measures used by participants. Thereby, the findings continue to add to our understanding of the instruments involved in earnings management practices across hierarchical levels, which is necessary given that middle managers significantly outnumber top managers.

Previous research often relies on public archival data (Abernethy and Wallis 2019) or on the assessments of third parties, like analysts, to identify managers’ methods (e.g., Khan et al. 2019; Lev and Thiagarajan 1993). Given the already-inherent difficulties of earnings management models (e.g., Dechow et al. 2010; DeFond 2010), the variety of accounting and real actions and the diversity of motivations outside the pressure of capital markets highlight that each case of earnings management is different and thus suggest that any one of the academic models on its own might be insufficient to approximate earnings management. The sample at hand is therefore uniquely suited to exploring middle managers’ practices by directly accessing this withdrawn group of semi-executive employees. While survey research suffers from its own methodological issues, it also provides an avenue through which to examine otherwise unobservable characteristics, such as managerial intent and motivation. Well-known panels (e.g., the German Business Panel and WHU Controller Panel) regularly provide insights into financial and management accounting-related topics (for overviews and examples, see Bischof et al. 2022 on the German Business Panel and Schäffer and Weber 2012 on the WHU Controller Panel). However, these panels are based on other target groups, such as top management. To our knowledge, there is no accessible data source from which private information on middle managers can be derived. Since the analysis of middle managers’ earnings management motives and practices also places special demands on the data, we carefully collect the data directly from its source. We thereby ensure an insightful and target-oriented database for our analyses.

Overall, the evidence of earnings management practices in middle management should also prove to be of practical value for standard setters, regulators, auditors, and investors in allocating their resources. Particularly with regard to the deficiencies identified by Healy and Wahlen (1999), we demonstrate that earnings management is likely to be material, pervasive, and frequent at middle levels of the hierarchy and point out common methods. The limitations and motivations presented provide indications to help identify and—where necessary—restrict the occurrence of earnings management to improve earnings quality.

This paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 develops the theoretical background and the research questions. Section 3 outlines the research method, and Sect. 4 presents the results. Section 5 concludes the paper by discussing the results and limitations.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Middle managers and earnings management

Even though there are vast amounts of research on earnings management (for reviews, see for example Dechow et al. 2010; Healy and Wahlen 1999; Walker 2013), most of the studies examine top management’s earnings management and, consequently, consolidated financial statements at the ultimate parent level (Beuselinck et al. 2019). Thereby, the literature assumes explicitly or implicitly that top executives are largely responsible for organizational earnings management (Cheng et al. 2016). However, it is unlikely that top management is alone in managing earnings (Lambert and Sponem 2005). It is thus necessary to identify the parties involved in earnings management (Lo 2008). Consistent with the interview evidence from Merchant (1990), we expect middle management also to engage in earnings management. We identify middle managers, such as subsidiary and business unit managers, as subordinate agents of top management who have disciplinary authority over the junior managers reporting to them and their staff and thus act as an indispensable coordinating link between these hierarchical levels. In contrast to lower management, they are solely or jointly responsible for the financial result of their specific unit or group and are therefore equipped with substantial decision rights and by extension discretion over their respective delimited units but not for the company as a whole. Accordingly, they are authorized to represent their organization internally as well as externally within certain limits.

Literature about middle managers is largely absent, as is a more holistic approach to the corporate processes that result in earnings management (Healy 1999). Therefore, we first establish whether earnings management is at all relevant for middle managers. Precisely defining earnings management is difficult due to the inability to observe managerial intent, the driving force behind the concept (Dechow and Skinner 2000). For the purpose of this study, we adopt Healy and Wahlen’s (1999, p. 368) comprehensive definition: “Earnings management occurs when managers use judgment in financial reporting and in structuring transactions to alter financial reports to either mislead some stakeholders about the underlying economic performance of the company or to influence contractual outcomes that depend on reported accounting practices”. This definition also implies that not all users of accounting information are willing or able to uncover earnings management as it would not be successful otherwise (Fields et al. 2001).Footnote 2 To engage in earnings management, middle managers are required to possess the opportunity and incentive to influence accounting decisions (Rutledge and Karim 1999). Both are substantially rooted in the particularities of their position, namely the distribution of decision rights, the control system, and the information asymmetries.

2.2 Opportunities for earnings management

The size and complexity of their businesses require organizations to divide responsibilities and tasks. Consequently, corporate groups are often structured hierarchically (Gibbs 1995). This delegation of decision rights is an important element of organizational structures and enables a dispersed workload and managerial specialization as well as quicker and more profound decision making (Chong and Wang 2019). Thus, decentralized decision rights trickle down the corporate hierarchy and are consigned to middle managers (Abernethy et al. 2004), who command specific knowledge about their area of responsibility and are tasked with implementing top management’s policies in their units. Accordingly, their role is critical to the effectiveness and performance of the business as it is not feasible for members of top management to make every business decision themselves (Clinard 1983).

However, middle managers’ central position within the organization puts them in a highly tense position as they face pressure from all sides. The resulting role stress induces dysfunctional behaviour to cope with their situation (Maas and Matějka 2009). Frequently, accounting-based performance measures are employed within control and incentive systems to prevent such undesirable behaviour (Abernethy and Vagnoni 2004; Fauré and Rouleau 2011). To this end, the accounting measures employed need to reflect the relevant performance of the unit based on the decision rights allocated (Abernethy et al. 2004). While control systems, accounting standards, and CFO directives (“solid line”), among others, limit their latitude, middle managers’ familiarity with their unit’s performance paired with their decision rights enable them to use their remaining discretion effectively to exert an impact on the reported earnings. Fundamentally, the information asymmetries sustained by middle managers thus meet the necessary condition for earnings management (Schipper 1989). We further argue that middle managers’ information asymmetry-based ability to affect earnings is not only operational but also strategic.

First, on an operational level, middle managers are responsible for providing financial information and reports about their units. While financial reports are meant to reduce the information asymmetries between subordinate units and the parent company, these very information asymmetries can also be used by middle managers to their advantage. On the one hand, they may use the discretion available in accounting standards and corporate-wide accounting guidelines to affect financial statements. For example, they may influence asset valuation, depreciation, transfer pricing, and cost allocation (Indjejikian and Matějka 2012). On the other hand, middle managers are generally able to conduct real earnings management in accordance with their decision rights. In fact, their impact on transactions of this kind should be even greater than that of top executives due to their closer proximity to operations (Cheng et al. 2016). Eventually, the financial reports, and thereby the earnings of middle managers’ units, are reconciled on the corporate group level and are often tested for reasonableness (Beuselinck et al. 2019). Depending on the degree of integration by superior units—which accompanies a reduction in middle managers’ private information (Abernethy et al. 2004)—the detection risk of earnings management and influence of superior units on the reported earnings increases, thus limiting middle managers operationally.

Second, their ability to influence corporate accounting extends to a strategic dimension. Accounting policies are determined strategically by top management (Hagerman and Zmijewski 1979). However, middle managers are frequently involved in strategy making (Currie and Procter 2005; Wooldridge and Floyd 1990). Depending on their unit’s importance, they are thus able to exert their influence upwards on top management and promote their ideas regarding policy decisions or shape policies for their units (Currie 1999; Watson and Wooldridge 2005). In this respect, Indjejikian and Matějka (2012) find that only some of the companies that they examine impose common accounting policies on their business units. The remaining companies leave policy making entirely to their middle managers. Transferring such extensive authority improves decision making in business units but also increases management discretion. Finally, the interpretation and execution of the accounting policies is subject to the discretion and self-interest of the responsible managers.

2.3 Incentives for earnings management

Opportunity alone is insufficient to conclude that middle managers actually manage earnings. Managers would only be willing to manage earnings if they could reasonably expect benefits or, as Watts and Zimmerman (1990, p. 150) state, “Choices are not made in terms of ‘better measurement’ of some accounting construct, such as earnings. Choices are made in terms of individual objectives and the effects of accounting methods on the achievement of those objectives.” Indeed, the literature documents the opportunistic nature of accounting choices (Christie and Zimmerman 1994).Footnote 3

Under efficient contracting, governance and, in turn, contracting are optimal. Consequently, managerial opportunism could be described by a set of purely economic variables (Bowen et al. 2008). This explanation is already difficult to uphold, considering information asymmetries and the cost of contracting, but is not sustainable in practice given the multitude of influences. It can therefore be presumed that a variety of individual motivations, such as contractual, compensation, debt, and asset-pricing concerns, are involved in accounting choices (for overviews, see Fields et al. 2001; Healy and Wahlen 1999). In this context, relevant incentives for middle managers include (1) favourable performance assessments; (2) bonus achievement; (3) career advancement in the form of promotions as well as prevention of demotion and dismissal; and (4) preservation of reputation and control (Bouwens and van Lent 2007; DeFond and Park 1997; Guidry et al. 1999).

First, performance evaluations are partially based on accounting information (Indjejikian and Matějka 2012). Obviously, a better-informed middle manager has an incentive to present a less informed superior with adjusted numbers to improve the evaluator’s impression (Christensen 1982). Second, besides their individual performance evaluation, variable compensation is substantially based on accounting information (Cichello et al. 2009). Indeed, Bushman et al. (1995) find that the largest part of middle managers’ bonuses is determined by the performance of their unit itself, irrespective of their concrete hierarchical level (e.g., 46.3% for divisional managers). Smaller bonuses can also be sufficient because it is not the amount of a bonus that motivates middle managers but rather the achievement of one, according to Gibbs (1995). Depending on the target-setting mechanism, managers optimize bonuses over multiple periods by adjusting current accounting information to influence future income (Leone and Rock 2002). Third, promotions are generally associated with ability and thus with performance as captured by performance measures and accounting numbers (Gibbs 1995). In this regard, Cichello et al. (2009) reveal that, while the performance level has only a relatively small impact on promotions, better performance in comparison with other units of the same organization is strongly related to promotions. Thereby, they highlight the competitive system behind career decisions. On the flipside, inadequate individual performance leads to substantial monetary and social loss through demotion or even job dismissal (Cichello et al. 2009). The sensitivity of middle managers’ turnover to poor operating performance of their unit is further supported by McNeil et al. (2004). However, Gibbs (1995) questions whether fear of demotion and dismissal serves as a primary incentive. Fourth, Young (1985) argues that social pressure is a prime determinant of dysfunctional behaviour as subordinates might succumb to such pressure by aligning their personal goals with those of top management. Therefore, earnings management by middle managers can be prompted by social concerns regarding their reputation. Managers may have short-term incentives to improve their standing by reporting managed earnings. However, the literature notes that reputation has an opposite, disciplining effect in situations in which their actual performance can be inferred (Baiman 1990; Webb 2002). In a similar vein, middle managers may use earnings management to maintain or extend their power and control (Leuz et al. 2003). For this purpose, they must conceal their activities and set aside reserves to prevent intervention by superiors. Beyond classical agency theory, behavioural research (for an overview, see Abernethy and Wallis 2019) indicates that less rational motives for accounting decisions may also be rooted in individual managerial characteristics, such as a CFO’s style (Ge et al. 2011), overconfidence (Schrand and Zechman 2012), and narcissism (Ham et al. 2017).

However, we know relatively little about the concrete drivers of earnings management (Lambert and Sponem 2005). Given the different transactions and different corporate and personal environments, it is reasonable to assume that the motivations of middle managers vary and therefore so does their individual behaviour. In this respect, the outlined theory can only serve as a general starting point, which needs to be validated against reality. At the same time, these aims determine the actions taken to manage earnings (e.g., Marquardt and Wiedman 2004). For example, managers have incentives to increase earnings to meet predefined targets related to their compensation (Cheng and Warfield 2005; McVay 2006) or to debt covenants (Dechow et al. 1996). In contrast, managers may reduce earnings to create reserves to keep future targets achievable (Leone and Rock 2002) or to prevent future dismissals due to bad performance (DeFond and Park 1997). Which motives actually apply is ultimately an empirical question, the answer to which depends on the individual circumstances. Accordingly, we ask the following research question:

RQ1: What motivates middle managers to conduct earnings management?

Taken together, middle managers have both the opportunity and the incentives to manage earnings. Arguably, both increase with increasing information asymmetry. Consequently, we argue that these circumstances give rise to earnings management. However, not all middle managers may be willing to take the involved risks, or they may not be able, or only to a limited degree, to engage in earnings managements due to given limitations (e.g., the disciplinary power of the top management). Considering the aforementioned arguments, we pose the following research question:

RQ2: To what extent do middle managers engage in earnings management?

Simultaneously, the tense environment in which middle managers operate and the previous arguments illustrate the variety of factors and stakeholders that affect their earnings management practices. Top management, ownership, and subordinates all expect them to fulfil their often-changing and opposing demands. While usually not directly subject to capital markets, the expectations of analysts, shareholders, and other capital market participants are nevertheless relayed to them by top management. Consequently, they are exposed to a dynamic environment in which stakeholders’ contradicting and unclear expectations lead to role conflicts and role ambiguity for middle managers (Currie and Procter 2005). We are especially interested in the determinants that limit the opportunities for earnings management a priori. In this regard, we state the following research question to gain a broad overview:

RQ3: What are the factors that limit middle managers’ earnings management?

3 Research method

3.1 Measuring earnings management

As indicated, earnings management is conceptually related to information asymmetries. It is not observable and is not intended to be (DeFond 2010). Accordingly, it is difficult for all interested parties, including researchers, to identify earnings management reliably. Much research focuses on accrual measures (Dechow et al. 2010; Roychowdhury 2006). The corresponding approaches discern abnormal and, therefore, discretionary accruals from normal accruals explained by firm observables. However, criticism of these methods, employed by academics to detect earnings management, has accumulated.

Ball (2013) discusses the shortcomings of accrual models at length, noting that discretionary accruals are often overidentified. As a result, the alleged amounts of manipulation are unrealistically large, even though the underlying items—mostly working capital—are relatively easy to audit. This makes it difficult to identify true manipulation (Khan et al. 2019). McNichols (2000) notes that companies with greater expected earnings growth will be especially likely to exhibit greater accruals. Hribar and Collins (2002) criticize the indirect approach of calculating accruals with balance sheet data despite the availability of accruals in the statement of cash flows. They support Ball’s (2013) assessment by stating that the calculation of discretionary accruals is thus biased, potentially leading to false positives for earnings management, which they demonstrate for mergers and acquisitions and discontinued operations. Dechow et al. (2019) point out that the set of variables used in accrual models is not yet refined. Accruals with different economic, accounting, and statistical attributes are unreflectingly combined. As a result, the models are too coarse to capture subtle signals, which can be identified through the fundamental analysis employed by Khan et al. (2019). Some of the issues can be ascribed to neglected earnings dynamics, omitted variables, measurement error, Type 1 and Type 2 errors, and simply lacking knowledge (Ball 2013; Dechow et al. 2010; Gerakos 2012). In addition, Hribar and Nichols (2007) simulate issues with models of absolute (“unsigned”) discretionary accruals, finding a biased tendency to reject the null hypothesis.

Different approaches are suggested in response to these problems. First, besides accounting data, information from governmental agencies could be used, such as SEC Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases (AAER) and earnings restatements (e.g., Dechow et al. 1996), although the sample sizes tend to be small and are potentially subject to selection bias (Dechow et al. 2010). Second, data and opinions from professional parties could provide insights. For example, Khan et al. (2019) use data from a research firm and Brown et al. (2015) use survey analysts. Third, management could be asked directly in interviews and surveys (e.g., Dichev et al. 2013, 2016; Graham et al. 2005). Regarding the research questions at hand, it is necessary to access middle managers directly.Footnote 4 However, accounting information for subsidiaries is generally difficult to obtain (Beuselinck et al. 2019). Financial reporting and databases usually provide mostly consolidated information for corporate groups. Therefore, archival studies lack the potential to evaluate middle management inside the black box that represents the company. Additionally, it is imperative to detect the managerial motivation and intent. While not without issues on its own, which are addressed subsequently, a survey-based research design mitigates the aforementioned problems and allows researchers to gather data on the factors that affect practitioners’ decision making and behaviour (Dichev et al. 2013). Specifically, a survey approach enables us to avoid earnings management proxies and receive information about earnings management directly from the sources. Furthermore, subjective assessments can only be obtained by directly addressing the individuals, which applies here to the perceived limitations and otherwise unobservable motivations. Therefore, the survey approach contributes to the understanding of the managerial intent that drives earnings management practices.

3.2 Survey design

To answer our research questions, we use a structured questionnaire to collect data on middle managers with accounting responsibilities in the executive branch. The survey outline is broadly based on the research design by Dichev et al. (2013, 2016) while taking into account the most recent insights provided by the earnings management literature as well as the available research on middle management. We consider concerns raised in the literature regarding the use of survey data in accounting research (e.g., Hiebl and Richter 2018; Ittner and Larcker 2001; Speklé and Widener 2017; Van der Stede et al. 2005). To improve the questionnaire’s quality and relevance to both research and practice, we engage in thorough pre-testing. In particular, we follow a two-stage pre-test procedure to validate the questionnaire. In the first stage, five academics with expertise in the fields of earnings management and/or survey research provide feedback on the instrument’s content, wording, and design. In the second stage, the questionnaire is pre-tested with five middle managers from different companies; these practitioners do not participate in the final study. After the practitioners have filled in the questionnaire, we conduct individual semi-structured interviews via phone between 6 September 2018 and 19 September 2018. We choose this approach for its higher flexibility compared with structured interviews (Abernethy and Lillis 1995; Bell et al. 2018). The method allows us to obtain detailed feedback and ask follow-up questions and permits the respondents to address additional, previously not mentioned, aspects. By employing this second step, we ensure that the questions are generally understood and interpreted in accordance with their intent and reduce the likelihood of neglecting issues that are not represented in the academic literature (Dichev et al. 2013).

The final questionnaire is structured in accordance with the research questions and consists of eight thematically differing sections. Considering the evidence in the literature (Matell and Jacoby 1971) and following the example of Dichev et al. (2013), we opt to use predominantly five-point Likert response scales. We rely on subjective measures throughout the questionnaire, which is regarded as an appropriate approach due to the unavailability of data at the middle management level (Van der Stede et al. 2005). At the beginning of the questionnaire, the term “earnings” is explicitly defined as “earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT), as reported in the profit and loss statement according to the primarily used accounting standards” to guarantee a uniform understanding of the concept among all the respondents, to eliminate alternative explanations that are not related to earnings management, such as taxation (Beaver et al. 2007), and to exclude interest, which cannot be influenced, while including depreciation and amortization, which can be used to distribute earnings (Hillier and Willett 2006). The central survey instruments used to reflect earnings management are modified versions of those by Dichev et al. (2013). These are extended to include real earnings management. Thereby, the instruments comprehensively cover different manifestations of earnings management without limiting the respondents. Other instruments used in the literature (e.g., Merchant 1990) primarily concentrate on specific aspects of (real) earnings management, which would only partially cover this study’s research focus. To help the respondents gain a common understanding of the concept, before asking the questions, we define the term “earnings management” as “Deliberate influence on accounting that will have an impact on earnings in this or (a) later period(s). This includes measures that reflect accounting actions (e.g., accruals; recognition, valuation, reporting and disclosure choices) and real actions of factual design (e.g., order and project shifts; temporary reduction of expenditures for research & development, advertising).” We carefully word the definition objectively to avoid any positive or negative connotation.

The survey is conducted in Germany and accordingly delivered in German to enhance comprehension. Germany is especially suitable for this study’s purpose as it features distinctive middle managers, whose responsibilities are comparable to those of managers from other countries who focus on technical problem solving (Delmestri and Walgenbach 2005). The German Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) represent code law, which differs from common law, especially in terms of conservatism and timeliness (Ball et al. 2000; Fülbier et al. 2008), and is therefore viewed as being prone to earnings management, especially earnings smoothing (Soderstrom and Sun 2007). However, there seems to be no difference in the level of earnings management when comparing the German GAAP with presumably high-quality standards like the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) (Van Tendeloo and Vanstraelen 2005).

3.3 Sample selection

To create our target sample and collect data on these firms, we use the Dafne database from Bureau van Dijk, which provides comprehensive information on companies in Germany. We focus on medium-sized and larger firms, exceeding 6 MEUR in total assets, 12 MEUR in sales revenues, and 50 employees, in accordance with the size limits of the German GAAP (see § 267 Handelsgesetzbuch (HG), 2017). We exclude small companies due to their comparatively insignificant opportunities to manage earnings based on their size. Financial and insurance companies are excluded because regulatory requirements materially alter their balance sheet and income statement. Additionally, only firms with a parent company that owns at least 50.01% of shares directly or indirectly are included. This is further confirmed by the BvD independence indicators (C and D) and a manual check where possible. The total sample provided by Dafne consists of 13,879 companies. We then randomly select approximately 10% of the companies to generate our random sample. After manually adjusting for closed, merged, and otherwise no longer existing firms, the final random sample contains 1,164 companies.

To increase the likelihood that the questionnaire will reach the intended middle managers, we subsequently identify and address the questionnaires to middle managers with accounting responsibilities in 924 of the previously identified dependent companies. Specifically, we select current managers with responsibility for the whole subsidiary, division, or unit (e.g., CEO) or, if applicable, for finance and/or accounting (e.g., CFO). The specific job titles differ due to the different legal forms present in the German corporate landscape.Footnote 5 No respective middle manager can be identified for 241 companies; thus, these questionnaires are sent out without personalization.

To improve the response rate, we follow the tailored design method (Dillman et al. 2009). Specifically, we use four contacts before and during the survey administration in October and November 2018.Footnote 6 With regard to the sensitivity of the topic and the responses, the survey is anonymous. The respondents disclose neither their names nor their corporate affiliations. In total, 87 questionnaires are returned (44 online, 5 via e-mail, 1 via fax, and 37 via mail),Footnote 7 representing a response rate of 7.47%; 77 of these are usable (6.62%), as detailed in Table 1. While a low response rate is expected for higher hierarchical ranks (Hiebl and Richter 2018), the response rate is lower than reported by previous surveys in accounting (for an overview see, for example, Hiebl and Richter 2018; Van der Stede et al. 2005) but comparable to the predecessor studies by Graham et al. (2005) with 10.4% and Dichev et al. (2013) with 5.4%.

3.4 Methodological issues

We conduct several analyses to assess the generalizability and self-selection bias in the sample. First, we test whether the respondents and initially contacted firms differ in firm size (as measured by revenues) or in legal form, as shown in Appendix A, Panel A. The analysis reveals no significant difference in revenues between the respondents and the target population. However, the number of questionnaires received is significantly higher (lower) for public (private) firms than expected (p < 0.001), albeit not necessarily different in terms of the non-response analysis in Appendix A, Panel B (p = 0.096). Nevertheless, this could indicate non-response bias and limit the generalizability of the results in the sense that systematically more (fewer) managers from public (private) companies might have participated in the survey. Private companies are potentially more secretive with their information, and managers may therefore not have responded. A comparison of the responses of managers from publicly traded companies with those of managers from privately held companies shows no differences in the motives for and extent of earnings management (untabulated). Differences in terms of limitations are discussed in Sect. 4.6 and documented in Appendix C.

To assess the non-response bias further, we conduct a test of early–late respondents, which assumes structural similarity between late respondents and non-respondents (Arnold and Artz 2015). Comparing responses before the first follow-up procedure and after the second (and last) follow-up procedure (Van der Stede et al. 2006), no differences are found for revenues, legal form, or any variable for earnings management at the 5% significance level, as shown in Appendix A, Panel C. The results do not change if we compare the earliest and the latest third of the respondents instead (untabulated). We can thus conclude that non-response bias is overall limited but must be considered when interpreting the results. Regardless of the outcomes of these tests, the response rate and sample size are unsatisfactory. We acknowledge that the results may therefore not apply to the general population of middle managers and phrase our results accordingly.

We rely on middle managers’ self-reported responses as our sole data source. This approach involves the risk of common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003). However, we address potential issues in the design of the questionnaire as well as by ex-post testing. In particular, we guarantee the respondents’ anonymity, state that there are no right and wrong answers, and ask the respondents to answer the questions honestly (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Additionally, we use best practices to design the questions and pre-test the questionnaire carefully to detect problematic questions (Speklé and Widener 2017). Further, common method bias is ascribed to several factors, such as social desirability, negative affectivity, and acquiescence (Spector 2006). For this study, social desirability is especially threatening due to the sensitive nature of the topic. Previous studies find potentially confounding effects of different magnitudes caused by social desirability (Moorman and Podsakoff 1992; Ones et al. 1996). Thus, we test for socially desirable responding by adopting the scale from Crowne and Marlowe (1960) as applied by Paker and Kyi (2006). Moreover, this factor may serve as a fundamental version of a marker variable (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Factor analysis identifies two factors with satisfactory factor loadings, construct validity, and convergent validity, as shown in Appendix B, Panel A. The correlation analysis in Appendix B, Panel B does not reveal any significant correlations of the social desirability factors with the earnings management measures. Finally, we conduct Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff and Organ 1986). The results of the unrotated exploratory factor analysis reveal a multi-factor solution for the central variables (untabulated). Thus, the results suggest that common method bias is not likely to be a serious issue for this study.

Additionally, the research design carries the risk that hypothesis guessing may bias the participants’ responses. By trying to guess the purpose of the study and thereby the expected survey outcomes, respondents may actively distort the baseline level of central constructs, such as earnings management. On the one hand, asking respondents about the extent of earnings management may imply a “normal” level of earnings management, thus potentially biasing the responses upwards. On the other hand, earnings management is controversially discussed and negatively connoted in the literature and the media (Elias 2002). Respondents may therefore admit to little or no earnings management as they may anticipate the examination of the ethical aspects of the practice. To prevent bias in either direction, we use the foundations of a proven research design and carefully phrase the questions neutrally. We specifically scrutinize the critical questions regarding the magnitude of earnings management during the pre-test. The feedback from the participants in the pre-test does not suggest any particular issues. The length of the questionnaire further reduces the likelihood that respondents will engage in hypothesis guessing for every construct (Appendix D). While not definite tests of hypothesis guessing, the number of respondents who report zero earnings management (20.00%), the standard deviation (8.01), and the extent of differences in responses (10 different percentages given in the free text field) suggest a certain degree of diversity in the responses. Overall, however, we cannot rule out hypothesis guessing.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Summary statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of the sample firms. These are mostly public companies (57.14%) with mean revenues of 500–999 MEUR and a mode of 100–499 MEUR (44.74%). However, the insights regarding the influence of the company size on earnings quality are ambiguous. Early studies find negative effects due to an increased political focus accompanied by increased regulation and taxation costs (Hagerman and Zmijewski 1979; Jensen and Meckling 1976). More recent studies assume the contrary as smaller firms are unable to afford internal control systems (Doyle et al. 2007a, b). Accordingly, small organizations exhibit an increased likelihood of correcting reported earnings (Kinney and McDaniel 1989). Profits were reported in the last fiscal year by 84.42% of the firms. Most firms are from the energy and disposal sector (16.88%), followed by the chemicals and pharmaceuticals (12.99%) and automotive (11.69%) industries. The combination of IFRS and German GAAP is the set of standards most often applied (46.75%), followed by the German GAAP only (24.68%) and the IFRS only (14.29%). A large majority of the surveyed firms are audited by one of the Big Four auditing companies (84.21%). The Big Four are associated with high-quality audits, reliability, and, in turn, fewer discretionary accruals because of their high reputation, resources, and assumed independence (Kim et al. 2003; Teoh and Wong 1993). In comparison, the ratio of public (45.07%) to private (54.93%) is reversed in the US sample of Dichev et al. (2013). The companies also report more revenue (mean: USD 5,473.72 million), reflecting an overall population with higher revenues on average (USD 2,641.07 million) and fundamental differences between the US and the German economy. In contrast to the more even sector distribution in this paper, Dichev et al.’s (2013) sample is skewed towards manufacturing (32.63%), followed by the retail/wholesale (13.66%) and financial (11.58%) sectors.

Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics of the sample of middle managers. The managers are mostly male (89.61%), aged between 40 and 59 (84.00%), and have a university degree (80.26%). The managers have backgrounds in financial accounting (41.33%), general business administration (21.33%), or management accounting (17.33%). Their job tenure, on average, is between 4 and 9 years. Accordingly, these descriptive results indicate that middle managers who are responsible for accounting are experienced and most have been trained in accounting. Nearly all the respondents have a professional background in accounting or related areas. We therefore expect them to have the competence to conduct earnings management and be aware of their actions and the potential consequences. Additionally, most managers have quantitative earnings targets (68.83%). Most of the managers in Dichev et al.’s (2013) sample are also between 40 and 59 years old (75.89%), and nearly all hold a university degree (99.46%). As in the present sample, the majority of managers have a background in financial accounting (43.20%) and an average job tenure of 4–9 years. In summary, the surveyed firms tend to be larger in Dichev et al.’s (2013) sample while the demographic and personal characteristics of the managers in the two samples are rather similar.

4.2 Earnings quality

To classify the subsequent results on earnings management, we first look at the attributes that characterize earnings quality for the surveyed middle managers. Specifically, we ask the survey participants which aspects they believe to capture high-quality reported earnings. According to Table 4, the participating middle managers place strong emphasis on earnings persistence. Persistent earnings are considered stable and low risk (Ewert and Wagenhofer 2011), thus increasing earnings predictability (Barker and Imam 2008). In particular, the agreement (a choice of 4 or 5 on a scale from 1 to 5) is the highest for sustainability of earnings (92.11%), consistency of reporting choices over time (82.89%), and avoidance of unreliable estimates (77.64%), while usefulness as a predictor of future cash flows (48.00%) is viewed as important by nearly half the respondents. Brown et al. (2015) find that analysts make comparable assessments of earnings quality.

The German GAAP is considered to be particularly conservative, which presumably affects accounting practitioners’ education and mindset (Ball et al. 2000). Moreover, evidence from the interviews by Dichev et al. (2013) suggests that earnings understatements can be implemented more easily than overstatements because auditors do not examine them as closely. Remarkably, however, only about every second respondent agrees that conservatism is an important attribute of high-quality earnings (50.67%). The torn opinions support the previous discussion on the role of conservatism in earnings quality (Penman and Zhang 2002). Additionally, approximately half of the respondents agree that less need for explanation (56.58%) and accruals that are eventually realized as cash flows (47.37%) determine high-quality earnings. Although the importance of the items evaluated generally tends to be lower than in the previous top management study by Dichev et al. (2013), the assessments largely align with those of top management, especially in terms of earnings persistence. However, in contrast to top management, middle management places less importance on the absence of one-time and special items (25.23%). This may indicate that one-time items often result from operational business decisions (Parfet 2000).

4.3 Earnings’ uses

Standard setters have acknowledged the many uses and users of earnings (Holthausen and Watts 2001). To sort this diversity, we next analyse the recipients and purposes of earnings. In particular, the recipients of earnings are the potentially aggrieved parties of earnings management. It is therefore essential to determine which persons and purposes are actually impaired (Lo 2008).

Overall, a large majority of the surveyed middle managers report their earnings for internal as well as external purposes (n = 77; 81.82%; untabulated). It is rare that their earnings are used only for internal (16.88%) or only for external purposes (1.30%). Table 5 shows the importance (a choice of 4 or 5 on a scale from 1 to 5) and unimportance (a choice of 1 or 2) rates of specific recipients and uses of earnings, rank ordered by mean. In line with their hierarchal duties, these middle managers identify management as the most important recipient of their reported earnings (85.71%). Use by management dominates all other uses of earnings, as evidenced by its average rating, which is significantly higher than that of all the other items (all p < 0.01). Following in importance are use for management compensation (77.63%), use as a basis for evaluations by superiors (75.00%), use by the board (71.62%), use by investors (68.42%), and use by financial institutions (47.37%).

While the uses listed above already give an indication of the personal importance of earnings for the surveyed middle managers, the data provide additional evidence that earnings are the measure against which these middle managers are evaluated. In particular, 68.83% (untabulated) of the managers receive formal quantitative targets based on earnings. A look at their financial bonus further substantiates the impact of earnings on the managers’ personal income. Of the managers who receive earnings-based targets, the earnings targets of only 11.32% are not linked to a financial bonus, whereas a majority reports that up to 24% (28.30%) or between 25 and 49% (32.08%) of their bonus depends on achieving their earnings target. We therefore conclude that earnings are at least one of the relevant performance measures for most of this sample’s managers and are used as both a target and an incentive.

As displayed in the last two columns of Table 5, where possible, we additionally compare the indicated earnings uses of this survey’s middle managers with the assessments of top management from Dichev et al. (2013). While top managers rate the use by investors to value the company highest and thus attribute greater importance to the valuation role of earnings, the four most important recipients and purposes stated by middle managers can be ascribed to the stewardship role of earnings.Footnote 8 Valuation by investors is rated significantly lower by middle management than the previous ratings by top management (p < 0.001). Three reasons— or a mixture thereof—are conceivable for this difference. First, justified by hierarchy, top managers mainly deal with capital markets and private investors, while middle managers with accounting responsibilities have an internal focus and assist top management with investor communication if necessary. Second, country-specific variations might be responsible for the difference. In particular, the capital market orientation of companies in the US is stronger than that in Germany. German companies primarily rely on self-financing and borrowing from their house banks (Dumontier and Raffournier 2002). However, noteworthy in this regard is that fewer than half of the respondents indicate that their reported earnings are important for use by financial institutions. Third, the capital market exposure of the surveyed firms may be lower due to selection and country-specific effects.

4.4 Motivations for middle managers’ earnings management

To assess middle managers’ earnings management, we first investigate RQ1 and thus the motivations of middle managers to manage earnings. The interpretation of the motivations listed in Table 6 paints an interesting picture. First, there is no single motive that satisfactorily explains the actions of all the surveyed middle managers. In fact, none of the listed items reaches 50% agreement overall (a choice of 4 or 5 on a scale from 1 to 5). All the comparable agreement rates are significantly lower than those of top management (Dichev et al. 2013). Second, the results indicate that 90.54% of the respondents agree somewhat with at least one motivation (at least one choice of 3 or higher on the 5-point scale), while 71.62% of the respondents agree or agree fully with at least one motivation (at least one choice of 4 or 5). Accordingly, while no single motivation is consistently found to be important for all the participants, the entirety of the listed items adequately reflects the diversity of reasons for earnings management. The results thus also emphasize that the surveyed middle managers’ motivation depends on their particular situation.

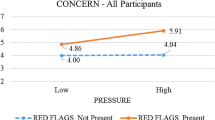

The most important motivations in this sample are meeting targets (40.28% agree), earnings smoothing (35.21%), superiors’ orders (32.88%), reducing future expectations (36.99%), and superiors’ pressure (33.33%). Following these five items, there is a substantial drop-off in agreement. Target beating and earnings smoothing are widely discussed and acknowledged in the literature (for an overview, see Dechow et al. 2010). As indicated earlier, middle managers are often given targets for their subunits. Besides these formalized targets, other benchmarks, such as losses, earnings decreases, and missing external expectations, apply (Degeorge et al. 1999). Firms in financial distress are considered to be particularly prone to target beating as they stand to gain the most from this practice (Cheng et al. 2016; Jiang 2008) and try to avoid debt covenant violations (Franz et al. 2014). However, for this sample, target beating and the debt-to-equity ratio are uncorrelated (ρ = 0.07; p = 0.593), which might be attributable to a potential self-selection effect. In particular, the pressure resulting from high levels of debt may tempt managers to conduct excessive earnings management, which in turn could be a reason why they did not participate in the study.

Previous research documents managers’ strong preference for a smooth earnings path to convey the impression of lower firm risk (Graham et al. 2005). This also applies to the valuation of organizational business units (Dierkes and Schäfer 2021). Earnings smoothing can lead either to upward or to downward earnings management. Specifically, managers smooth earnings to avoid missing targets or to generate reserves by spreading profits to future periods (DeFond and Park 1997). While the first explanation overlaps with target beating, the second explanation of earnings smoothing and reducing future expectations suggests that managers possibly recognize too much bad news (cf., Kothari et al. 2010), use economically favourable conditions to establish reserves, and try to prevent targets from ratcheting (Leone and Rock 2002). This is consistent with the previous result regarding the predominance of income-decreasing earnings management in this sample.

Again, we observe that superiors exert an impact on middle managers’ behaviour. Approximately one-third of the respondents report conducting earnings management because of superiors’ orders and superiors’ pressure; 21.13% agree with both. Accordingly, these two motives are highly correlated (ρ = 0.58; p < 0.001). The influence of superiors in this sample is in line with Beuselinck et al. (2019), who find that headquarters may request their subsidiaries to adjust their earnings.

In sum and with regard to RQ3, we observe two central patterns: first, the intent not to violate demands—either in institutionalized form, like targets, or personal expectations—and, second, the creation of reserves. Consequently, the surveyed middle managers seemingly prefer to report consistent earnings patterns over time, which is understandable because negative earnings surprises are generally considered to be bad (Brown and Pinello 2007). This is also consistent with the high importance that the respondents attribute to the persistence of earnings. Managers may thus consider their actions, such as earnings smoothing, to be “reasonable and proper” (Parfet 2000, p. 485) and beneficial for earnings quality.

Surprisingly, incentives, regardless of their manifestation, have only a negligible influence on this sample, although middle managers’ reported earnings are often used for compensation purposes, as shown above. In this respect, the surveyed middle managers differ from top managers, who have regularly been shown to increase their compensation by managing earnings (e.g., Bergstresser and Philippon 2006; Burns and Kedia 2006; Cheng and Warfield 2005; Dichev et al. 2013). A potential explanation for this finding is the longer expected tenure of middle managers. It is therefore reasonable for middle managers to refrain from purely short-term-oriented earnings management actions to achieve incentives. Rather, they seem to take a long-term approach, which is supported by the evidence that they create reserves, as mentioned above. However, this conclusion is somewhat at odds with the results reported by Guidry et al. (1999), who find that middle managers use earnings management to reach bonus targets. Potential self-selection effects due to differences in company size and financing should be taken into account when interpreting this finding. These could lead to a shift in the importance of different types of incentives, especially for bigger, capital market-oriented companies.

Additionally, despite the pressure applied to the middle managers of this sample, they do not seem to be afraid of adverse career consequences. No middle manager who reports increased pressure (a choice of 4 or 5) agrees that they fear negative career consequences. Similarly, the present study cannot confirm that observing others manage earnings leads to imitation effects, as shown by Kedia et al. (2015). All of these results do not change when the legal form of the surveyed companies (public or private) is taken into account.

4.5 Extent of middle managers’ earnings management

The second research question focuses on the extent of earnings management. While investigating RQ2, we shed light on several supplementary aspects: (1) the proportion of middle managers who manage earnings, (2) the magnitude of this earnings management, (3) the frequency of occurrence, (4) the frequency of income-increasing and income-decreasing earnings management, and (5) the actions primarily taken to manage earnings. To facilitate comparability, we specifically define earnings management in terms of both accounting and real actions relating to the previously stated definition of earnings (i.e., reported EBIT; see Appendix D). Feedback from the practitioners’ pre-test indicates that negative repercussions (e.g., reluctance to answer the questions) are unlikely if we ask managers directly about their earnings management practices. Hence, we refrain from using surrogate terms in the questions and address the respondents directly.Footnote 9

Table 7 presents the key data. It shows that 80.00% of the respondents conduct earnings management in any given period, which provides initial evidence that earnings management might be a common practice for the middle managers of this sample but has to be interpreted with caution given the small sample size. The overall mean for earnings management amounts to 6.01% of total earnings, with a standard deviation of 8.01%. The number rises to 7.52% if only the respondents who indicate that they engage in earnings management are considered (n = 56; SD = 8.31%). The magnitude of earnings management is significantly different from zero (t = 6.23; p < 0.001) and greater than auditors’ customarily applied materiality threshold of 5% (Messier et al. 2005; t = 2.270; p = 0.027). The magnitude of earnings management does not differ based on firm size (n = 56; ρ = − 0.22; p = 0.101) or according to whether the company is audited by one of the Big Four (n = 55; t = 0.076; p = 0.940, two-tailed).Footnote 10 However, there are differences depending on whether earnings are defined as a formal target. Middle managers with an earnings target report earnings management of 7.29%, which is significantly higher than the 3.23% reported by managers without a formal target (n = 70; t = 2.791; p = 0.007).

Only 15.71% of the respondents seem to rely solely on accounting actions.Footnote 11 The remaining middle managers report substantial real earnings management of 5.61%. While manipulations of real activities are more difficult to detect and implicitly protected by the “business judgement rule” (Lo 2008), resulting in less scrutiny by auditors and regulators, the magnitude in this sample is somewhat surprising. Middle managers usually have a longer employment horizon than top executives, making them more dependent on their future income (Cheng et al. 2016; Graham et al. 2005). It would therefore be counterintuitive for them to destroy future firm value both on their level and on upper levels through real earnings management as they might desire to rise in the hierarchy. Consequently, it is in their own interest for their means to be the least destructive possible, which is supported below.

On average, the surveyed middle managers managed earnings a little less than every second year over the last 10 years (mean = 4.79 years; SD = 3.71). In detail, as apparent from Table 8 1.4% of participants report earnings management only once. In 80.4% of cases, earnings management occurred repeatedly during the considered 10-year time span. Moreover, 25.35% of the respondents engage in earnings management every year. Interestingly, and in contrast to the magnitude of earnings management, the frequency of occurrence does not differ between the managers with earnings targets and those without (mean = 4.77 vs. 4.83 years; t = − 0.056; p = 0.956), suggesting that the participants do not base their decision on whether to manage earnings at all on their targets. If earnings management occurs, income-increasing earnings management is reported in a little more than one-third (36.97%) of the years. Accordingly, we infer that the middle managers in this sample tend to manage earnings downwards (63.03%). The difference is statistically significant (t = − 2.396; p = 0.019, two-tailed). Of the respondents who engage in earnings management, 33.93% only decreased income during the last 10 years. In this sense, the results correspond not to big bath interpretations but rather to cookie jar reserves for increased flexibility (Dechow et al. 2012). This is astounding as the literature and auditors generally tend to assume upward earnings management (Nelson et al. 2002; Walker 2013). Conversely, middle managers’ employment horizon is usually longer than that of top executives (Cheng et al. 2016). In this regard, it is reasonable that respondents use earnings management to hedge against future uncertainty, particularly in view of the conservative nature of the German GAAP, which can be considered advantageous for this purpose (Joos and Lang 1994). Additionally, the economic situations of many companies have been favourable during the surveyed time frame, which begins after the last economic crisis. As a result, these positive conditions enable and simplify downward earnings management.

In sum, we conclude that a sizeable number of the surveyed middle managers regularly conduct substantial earnings management. However, potential selection effects should be taken into account when interpreting the results. While managers with nothing to report might not have perceived any benefit in participating in the study, managers at the other end of the spectrum in particular may not have responded because of agency issues or questionable practices. Comparing this sample with that of Dichev et al. (2013), the results nevertheless impart the impression that more of the respectively surveyed middle than top managers manage earnings (80.00% vs. 18.43%) but to a slightly lesser degree (7.52% vs. 9.85%).

Thus far, there is little evidence of how exactly middle management manages earnings and whether the instruments used differ from those of top management. Accordingly, we ask the respondents to detail their actions. Specifically, the question reads as follows: “Which three actions in the balance sheet, profit and loss statement, or statement of comprehensive income are most frequently used by you to manage earnings?” Of the 77 respondents, 63 answered the question and provided between one and three items (179 selections in total). As shown in Table 9, the participants most often adjust provisions for their purposes (49 selections). This comes as no surprise as provisions are discretionary in nature and therefore relatively easy for the responsible manager to adjust. All the subsequent answers are provided noticeably less frequently. These reveal a mixture of accounting and real actions. Specifically, 29 managers state valuation adjustments, with impairment tests as the most common single item (5), 20 report transaction shifts, especially project and order shifts (9), and 19 mention working capital valuation and management, especially with regard to inventory (13). Actions regarding accruals and expenses and revenue are quoted equally often (11). The listed real actions can be characterized as rather cautious, with the exception of reductions in headcount in two cases. In line with the consideration of real earnings management in the literature, it is conceivable that the managers in this sample may thus try to avoid future adverse effects. Alternatively, they may lack the necessary organizational power to take more drastic actions.

In conclusion, while provisions seem to be the instrument of choice, the surveyed middle managers take several actions, both for accounting and for real earnings management. The list provided in Table 9 further confirms several of the signals used by analysts to determine earnings quality, as identified by Lev and Thiagarajan (1993).

4.6 Limitations of middle managers’ discretion

To shed light on RQ3, we examine the factors that limit managerial discretion. To this end, we begin by looking at the discretion allowed by accounting standards, which determine the theoretically (and legally) possible amount of accounting earnings management. In particular, we ask managers “How much discretion in financial reporting does the current accounting standard-setting regime in Germany allow?” on a scale ranging from 1 = “too little discretion” through 3 = “about right” to 5 = “too much discretion”. Most managers in this sample (75.34%) believe that the current discretion is about right (n = 73; mean = median = 3.00). Moreover, the relatively small standard deviation (SD = 0.58) shows that the respondents largely agree in this regard. Only one participant each selected one of the extreme points, indicating too little or too much discretion. According to this insight, the surveyed middle managers do not see a need for legislators to take action. Thus, tightening accounting standards may only shift earnings management towards real actions (Ewert and Wagenhofer 2005).

In line with these results, the respondents indicate that accounting standards moderately limit their reporting discretion (41.33% agree—a choice of 4 or 5 on a scale from 1 to 5) and are comparable to internal accounting policies (44.16%) in their importance, as shown in Table 10. However, when assessing the impact of accounting standards and internal accounting policies, there is a significant gap between the responses of managers of public and private companies. Regulatory requirements increase significantly once a company enters the capital market. Accordingly, the surveyed managers from public firms view accounting standards as more limiting than their private counterparts (t = 2.57; p = 0.013, two-tailed; Appendix C). Their assessment mirrors that of the top management from US public companies (average rating 3.52 vs. 3.72). The same applies to internal accounting policies, which need to reflect stricter regulation.

While Dichev et al. (2013) suggest overall dominance of external factors that may be attributable to country-specific effects (e.g., capital market influence), external and internal factors seem to have approximately equal impacts for the sample at hand. However, the only factors with approval of 50% or more among the respondents are auditors (50.00%) and internal controls (54.55%). Here, the higher auditor ratings than those of top managers might be attributable to the greater operative proximity of middle managers to auditors and thus increased personal scrutiny. Middle managers and auditors routinely resolve issues that therefore never reach top management. The limiting effect of auditors does not differ when comparing companies audited by Big Four audit firms with others (t = 1.21; p = 0.242, two-tailed) and when comparing public and private companies (t = 1.24; p = 0.220, two-tailed; Appendix C). Further, the respondents assess their superiors (i.e., top management and parent company) as limiting their discretion (46.05%). This assessment is consistent with the pressure on middle managers reported in the previous literature (Chong and Wang 2019; Clinard 1983). Accordingly, it is to be expected that superiors play an important role in the accounting practices of a number of middle managers.

Notably, the surveyed middle managers reveal a widespread disregard of juridical consequences. More than six out of 10 managers in this sample disagree that litigation risk limits their practice. The surveyed managers of public companies are somewhat more concerned about litigation than their counterparts from private companies (t = 2.88; p = 0.006, two-tailed; Appendix C) as they are presumably exposed to stricter controls and legal requirements due to their involvement in the capital market. Still, their approval rate is only 17.08%. Two explanatory approaches are conceivable in this respect. First, managers operate strictly within legal boundaries or, second, middle managers consider the probability of detection as low.

5 Summary and conclusions

Since Healy and Wahlen (1999, p. 370) state that “[d]espite the popular wisdom that earnings management exists, it has been remarkably difficult for researchers to convincingly document it”, research has been published that attempts to provide empirical evidence in this regard. Although there has been progress in many areas, middle managers have not yet received the same attention as other parties involved in the accounting process. Nevertheless, the literature suggests that middle management—endowed with decision rights and in a precarious organizational position—has the opportunity and various incentives to manage earnings.

The survey data collected provide deep insights into the participating middle managers’ earnings management practices from the motivations to the extent and the limitations. The results indicate that there is no uniform motivation for all the surveyed middle managers to pursue earnings management as none of the motivations mentioned in the survey find majority agreement. It is rather a variety of reasons that drive their actions—potentially depending on the situation. The most common motives for the participants are meeting their targets, smoothing earnings, reducing future expectations, and, superiors’ orders and superiors’ pressure.

Additionally, there is compelling evidence that the respondents manage earnings. A large majority of the middle managers surveyed report earnings management of approximately 7.5% of the reported EBIT on average in any given year. Remarkably, they predominantly tend to reduce earnings. This is consistent with recurring evidence throughout the survey that indicates their inclination for establishing reserves. To this end, they preferably resort to adjustments of provisions, valuations of assets and liabilities, and transaction shifts. This result can be reconciled with previous research on the specifics of the German GAAP (e.g., Joos and Lang 1994), which are regarded as being particularly conservative (Ball et al. 2000). As with the motivations, the impact of superiors on the participating middle managers’ practices emerges in the limitations on accounting discretion, in which superiors are identified as one of the most limiting factors, together with auditors, internal controls, internal accounting policies, and accounting standards.