Abstract

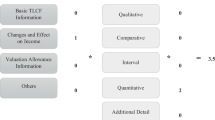

We examine the response of individual investors to firms’ adoptions of SFAS 109 – Accounting for Income Taxes. We predict that SFAS 109 reduces disclosure-processing costs and provides new decision-useful information, reducing the information disadvantage of individual investors relative to more sophisticated investors. Using monthly individual investor stock holdings data and staggered firm adoptions of SFAS 109, we provide evidence that individual investors increased their holdings in firms following adoption of SFAS 109. The increases are concentrated among more financially knowledgeable individual investors and among individual investors that are more likely to trade on financial statement information. We provide evidence that the increased demand among individual investors following SFAS 109 adoption is concentrated in firms with (i) tax attributes associated with less informative disclosures under the prior standard and (ii) substantive improvements to balance sheet reporting of deferred taxes and tax disclosures following SFAS 109 adoption. Results of a path analysis suggest that SFAS 109 adoption aided individual investors directly and indirectly via a decrease in analyst forecast dispersion. Collectively, the evidence is consistent with SFAS 109 benefitting individual investors by improving the accessibility and informativeness of financial reporting on income taxes. Our findings highlight the importance of evaluating how improved accounting standards can benefit a key stakeholder of the SEC and FASB: individual investors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study were obtained from Terrance Odean but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under a NDA for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Notes

Financial Accounting Standards Board Rules of Procedure, Amended and Restated through December 11, 2013.

Under the prior standard, APB 11, management had discretion in recording DTAs. As such, firms may have reported a deferred tax liability (DTL) on their balance sheet under APB 11 but reported a DTA on their balance sheet following SFAS 109 adoption. Appendix A, excerpt 2 provides one such example (Rohr) of significant changes in balance sheet reporting and tax footnote disclosures under SFAS 109. Section 2 includes an expanded discussion of SFAS 109.

Our sample period is prior to Regulation FD. As such, individual investors were likely to be at a greater information disadvantage regarding management expectations of future earnings (SEC 2000). With SFAS 109 adoption many firms made positive forward-looking statements as to why a valuation allowance was not recorded on some or all DTAs. Appendix A includes excerpts from tax footnotes, all of which make clear statements that valuation allowances are immaterial or not warranted given expectations of future profitability. Additionally, within our sample only two firms record a near full valuation allowance. Approximately half record a partial valuation allowance in the year of SFAS 109 adoption, with the average valuation allowance representing just 18 percent of the total DTAs. As such, within our sample of larger, profitable firms the additional information about DTAs, including that management has either not recorded a valuation allowance or recorded only a partial valuation allowance, was likely new and useful information to individual investors.

The agenda as of September 20, 2022, includes “Targeted Improvements to Income Tax Disclosures.” Available at https://fasb.org/Page/ShowPdf?path=FASAC-AGN.ATT_All-20220920.pdf&title=September%2020,%202022%20FASAC%20Meeting%20Handout.

In a comment letter to the FASB dated November 10, 2017, the four largest public accounting firms suggested changes to eight aspects of ASC 740 that are believed to be unclear, are applied inaccurately and inconsistently, or do not provide decision-useful information.

Individual investors are often viewed as less sophisticated relative to other investors, such as institutional investors (Barber and Odean 2000).

We use the individual investor data to measure financial knowledge, including employment in a “professional” occupation (as defined by the brokerage firm) and whether they self-assess their investment knowledge as good or excellent.

Data provided by the discount brokerage firm classifies individual investors as having a lower trading frequency if they trade less than 48 times a year.

The 75 percent, 25 percent split of the direct and indirect effect is calculated conditional on a decrease in analyst forecast dispersion. Using all observations (i.e., including those where analyst dispersion did not decrease), we find a 99 percent direct effect and a 1 percent indirect effect.

SFAS 109 adoption required managers to develop a more complete understanding of current and future tax liabilities. As such, management forecasts may have improved following SFAS 109 adoption, providing an additional indirect channel through which SFAS 109 could have improved the information environment for individual investors. Given data limitations, we have not performed analyses on the impact of management earnings guidance.

In response to the Disclosure Framework Project, the Big 4 firms cosigned a comment letter to the FASB on November 10, 2017. In the letter, they noted that “ASC 740 continues to be a frequent source of financial statement errors and restatements and we believe that there are additional changes that can be made to it to further reduce unnecessary complexity, and to be responsive to the FAF’s post-implementation review on FAS 109.”.

Specifically, each year, a current deferred tax liability or credit was calculated as the difference between (1) the tax liability calculated on the income tax return and (2) the tax expense calculated by multiplying the current tax rate by financial statement income less permanent differences between financial statement and taxable income. The current-year deferred tax liability was then recorded on the balance sheet [American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, Accounting Principles Board Opinion No. 11, Accounting for Income Taxes (Dec. 1967)].

Originally SFAS 96 was effective for years beginning after December 15, 1988. However, FASB Statements 100, 103, and 108 delayed the effective date to years beginning after December 15, 1989, 1991, and 1992, respectively.

FASB, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 109 – Accounting for Income Taxes (February 1992).

Financial Accounting Standards Board Rules of Procedure, Amended and Restated through December 11, 2013.

Institutional investors own 73 percent of the outstanding equity in the largest 1,000 firms on US exchanges, and high-frequency trading accounts for more than 50 percent of all US equity-exchange trading volume (Goldstein et al. 2014). These statistics suggest that it is unlikely that the overall market reaction to a change in the accounting standard captures how the change impacts individual investors, especially for accounting standards that differentially impact the information set of large institutional investors compared to that of individual investors.

Financial Accounting Standards Board. Proposed Accounting Standards Update, Income Taxes (Topic 740): Disclosure Framework – Changes to the Disclosure Requirements for Income Taxes (July 26, 2016).

We obtained the discount brokerage data from Terrance Odean at the University of California at Berkeley. This brokerage data consists of 158,034 individual accounts from 78,000 households. The data is a subset of the customers—1.25 million households—of the brokerage firm during the sample period. To extract a representative subsample the brokerage firm used stratified sampling to select household accounts classified as a general (60,000 observations), affluent (12,000 observations), or active-trader (6,000 observations) household.

Nonetheless, consistent with statements in Barber and Odean (2000), our findings may not generalize to retail brokerage accounts, as the trading practices of retail customers could differ from those of discount customers.

Our primary interest is the study of individual investors. However, the data used in our study is at the account level, and we acknowledge that an individual investor may hold multiple accounts.

We restrict our analysis to changes in holdings around the annual report release month. With this design choice, we can capture changes in individual investor holdings around the release of the annual report, which includes SFAS 109 adoption relative to changes in individual investor holdings around the release of the annual report in non–SFAS 109 adoption years.

Similarly, ΔHOLDINGSi,j,m-1,m+3 is the change in individual account i’s stock holdings in firm j from month m-1 to month m + 3. In supplemental analyses, we also consider an alternative dependent variable, the change in the natural log of the number of shares held. Our primary results are similar for this alternative dependent variable.

Given the frequent overlap in the adoptions of SFAS 109 and SFAS 106, we also evaluate the robustness of our results to alternative controls for SFAS 106 adoption and estimate our primary regression on the subsamples that do and do not have overlapping adoption. Please see Sect. 5.

We also evaluate the robustness of our findings to alternative fixed effect structures.

Our cutoff for low (high) trading frequency is based on classifications by the brokerage firm, which denote an individual account as “active” or having a high trading frequency if the account has 48 or more trades in a given year.

Our tabulated analyses employ industry, year, and treatment year fixed effects. However, in untabulated robustness testing, we re-estimate the results reported in Table 4 using firm, year, and treatment year fixed effects. We continue to observe a positive and significant coefficient on 109_INDICATE when the dependent variable is ΔHOLDINGS m-1 to m + 1 (coeff. = 0.004, t-stat = 4.07) and ΔHOLDINGS m-1 to m + 3 (coeff. = 0.004, t-stat = 3.24).

While the economic magnitude of the relative change in stock holdings is small, the change in stock holdings for the median individual account is zero, suggesting that SFAS 109 led to a change in trading behavior. To offer a reference point, Lawrence (2013) provides evidence that a one standard deviation change in the readability of a firms Form 10-K (measured using the FOG index) is associated with a 0.5 percent increase in annual individual investor holdings.

In column (2), which includes HIGH_NETDTA and the interaction of 109_INDICATE and HIGH_NETDTA, the main effect of SFAS 109 is outside of traditional statistical significance levels but is statistically significant at the 10 percent level based on a one-sided test.

For ease of interpretation of the interaction terms, Table 5 reports the results using indicator variables for firms with larger NOL carryforwards, larger net DTAs, and more volatile ETRs (HIGH_NOL, HIGH_NETDTA, and HIGH_ETRVOL). Results are generally similar to those reported in Table 5 if we use continuous measures. However, in estimating the interaction of 109_INDICATE and a continuous measure of ETR volatility when the dependent variable is ΔHOLDINGS from m-1 to m + 3 the t-stat for the interaction is 1.23, which is not significant at conventional levels.

Following prior research, such as Lawrence (2013), our primary research design requires an individual to own stock in firm j in the months before (m-1) and after (m + 1) the annual report filing month (m = 0) because it is computationally difficult to distinguish individuals that choose to not own stock (in firm j in month m-1) from missing data for individuals that enter our data set in month m + 1 (but were not present in month m-1).

Data limitations significantly reduce the sample size (N = 20,262) for the regressions reported in Table 8, Panel A that include the measure of individual account financial literacy (FIN_LITERATE).

The fully interacted model produces coefficients identical to those reported in columns (1) and (2), but by conducting the analysis in one model we are able to test for a difference in the coefficients on 109_INDICATE across the two samples. We conduct this analysis using subsamples and a fully interacted model (as opposed to a simple interaction) because the individual investor characteristics do not vary over the sample period.

We also run a fully interacted model which includes an indicator variable set to one if the firm’s balance sheet reported a net DTL before SFAS 109 adoption and a net DTA after and the interaction of this indictor variable with 109_INDICATE and all control variables. Similar to the analysis on individual investor characteristics, we conduct this analysis using subsamples and a fully interacted model (as opposed to a simple interaction) because the change in disclosure characteristics is measured in the year of SFAS 109 adoption and therefore is a stable firm characteristic over the sample period.

In addition to discussing the cumulative effect adjustment related to SFAS 109 adoption, many firms provide detailed information about specific sources of deferred tax assets and liabilities not provided under APB 11. Sample firms also provide more information about NOL and tax credit carryforwards and the realizability of deferred tax assets following SFAS 109 adoption. See the examples in Appendix A.

We do not include variables capturing the cumulative effect adjustment of SFAS 109 adoption (109_IMPACT) and SFAS 106 adoption (106_IMPACT) in the same regression, given high correlation.

References

Ayers, B. C. 1998. Deferred tax accounting under SFAS No. 109: An empirical investigation of its incremental value-relevance relative to APB No. 11. The Accounting Review 73(2): 195–212.

Barber, B.M., and T. Odean. 2000. Trading is hazardous to your wealth: The common stock investment performance of individual investors. The Journal of Finance 55 (2): 773–806.

Barber, B., and T. Odean. 2008. All that glitters: The effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. Review of Financial Studies 21: 785–818.

Bird, A., A. Ertan, S. Koralyi, and T. Ruchti. 2019. Does Financial Reporting Matter? Evidence from Accounting Standards. https://carlsonschool.umn.edu/sites/carlsonschool.umn.edu/files/inline-files/Steve%20Karolyi.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2022.

Blankespoor, E., E. deHaan, and I. Marinovic. 2020. Disclosure processing costs, investors’ information choice, and equity market outcomes: A review. Journal of Accounting and Economics 70 (2–3): 101344.

Blankespoor, E., E. deHaan, J. Wertz, and C. Zhu. 2019. Why do individual investors disregard accounting information? The roles of information awareness and acquisition costs. Journal of Accounting Research 51 (1): 53–84.

Bloomfield, R.J. 2002. The “incomplete revelation hypothesis” and financial reporting. Accounting Horizons 16 (3): 233–243.

Bloomfield, R.J., and T.J. Wilks. 2000. Disclosure Effects in the Laboratory: Liquidity, Depth, and the Cost of Capital. The Accounting Review 75 (1): 13–41.

Botosan, C.A. 1997. Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. The Accounting Review 72(3): 323–349.

Bratten, B., C. Gleason, S. Larocque, and L. Mills. 2017. Forecasting Taxes: New Evidence from Analysts. The Accounting Review 92 (3): 1–29.

Chi, S.S., M. Pincus, and S.H. Teoh. 2013. Mispricing of book-tax differences and the trading behavior of short sellers and insiders. The Accounting Review 89 (2): 511–543.

Chi, S., and D. Shanthikumar. 2018. Do Retail Investors Use SEC Filings? Evidence from EDGAR Search. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3281234. Accessed 26 Nov 2018.

Choudhary, P., A. Koester, and T. Shevlin. 2016. Measuring income tax accrual quality. Review of Accounting Studies 21 (1): 89–139.

Deaves, R., C. Dine, and W. Horton. 2006. How are Investment Decisions Made? Working Paper, Task Force to Modernize Securities Legislation in Canada.

Dechow, P.M., R.G. Sloan, and A.P. Sweeney. 1995. Detecting earnings management. The Accounting Review 70(2): 193–225.

Diamond, D.W., and R.E. Verrecchia. 1991. Disclosure, liquidity, and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance 46 (4): 1325–1359.

Dichev, I.D., J.R. Graham, C.R. Harvey, and S. Rajgopal. 2013. Earnings quality: Evidence from the field. Journal of Accounting and Economics 56 (2): 1–33.

DiPiazza, S.A., D. McDonnell, W.G. Parrett, M.D. Rake, F. Samyn, and J.S. Turley. 2006. Global capital markets and the global economy: A vision from the CEOs of the international audit networks. In Paris global public policy symposium. http://www.deloitte.com/dtt/cda/doc/content/dtt_CEOVision110806(2).pdf. Accessed 9 Dec 2022.

Dyer, T., M.H. Lang, and L. Stice-Lawrence. 2017. The evolution of 10-K textual disclosure: Evidence from Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Journal of Accounting and Economics 64 (2–3): 221–245.

Easley, D., and M. O’hara. 2004. Information and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance 59 (4): 1553–1583.

Espahbodi, H., P. Espahbodi, and H. Tehranian. 1995. Equity price reaction to the pronouncements related to accounting for income taxes. The Accounting Review 70 (4): 655–668.

Fama, E.F., and K.R. French. 1993. Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics 33 (1): 3–56.

Grossman, S.J., and O.D. Hart. 1980. Disclosure laws and takeover bids. The Journal of Finance 35 (2): 323–334.

Goldstein, M.A., P. Kumar, and F.C. Graves. 2014. Computerized and High-Frequency Trading. Financial Review 49 (2): 177–202.

Healy, P.M., A.P. Hutton, and K.G. Palepu. 1999. Stock performance and intermediation changes surrounding sustained increases in disclosure. Contemporary Accounting Research 16 (3): 485–520.

Indjejikian, R.J. 1991. The impact of costly information interpretation on firm disclosure decisions. Journal of Accounting Research 29 (2): 277–301.

Ivkovic, Z., J. Poterba, and S. Weisbenner. 2005. Tax-Motivated Trading by Individual Investors. American Economic Review 95: 1605–1630.

Khan, U., B. Li, S. Rajgopal, and M. Venkatachalam. 2017. Do the FASBs Standards add Shareholder Value? The Accounting Review 93 (2): 209–247.

Kim, O., and R.E. Verrecchia. 1994. Market liquidity and volume around earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics 17 (1–2): 41–67.

Kothari, S.P., X. Li, and J.E. Short. 2009. The effect of disclosures by management, analysts, and business press on cost of capital, return volatility, and analyst forecasts: A study using content analysis. The Accounting Review 84 (5): 1639–1670.

Kothari, S.P., K. Ramanna, and D.J. Skinner. 2010. Implications for GAAP from an analysis of positive research in accounting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2): 246–286.

Lambert, R., C. Leuz, and R.E. Verrecchia. 2007. Accounting information, disclosure, and the cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research 45 (2): 385–420.

Lawrence, A. 2013. Individual investors and financial disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics 56 (1): 130–147.

Lev, B., and D. Nissim. 2004. Taxable income, future earnings, and equity values. The Accounting Review 79 (4): 1039–1074.

Merton, R.C. 1987. A simple model of capital market equilibrium with incomplete information. The Journal of Finance 42 (3): 483–510.

Plumlee, M.A. 2003. The effect of information complexity on analysts’ use of that information. The Accounting Review 78 (1): 275–296.

Rego, S. O., B. M. Williams, and R. J. Wilson 2021. Does Corporate Tax Avoidance Reduce Individual Investors’ Willingness to Own Stock? https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2919004.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) 2000. Final rule: selective disclosure and insider trading. Exchange Act Release No. 33–7881 http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-7881.htm. Accessed 1 June 2022.

Sunder, S. 2002. Regulatory competition among accounting standards within and across international boundaries. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 21 (3): 219–234.

Weber, D.P. 2009. Do Analysts and Investors Fully Appreciate the Implications of Book-Tax Differences for Future Earnings? Contemporary Accounting Research 26 (4): 1175–1206.

Acknowledgements

All authors gratefully acknowledge helpful comments from an anonymous referee, Spencer Anderson, Jennifer Blouin (editor), Michael Calegari, Roman Chychyla, Matthew Erickson, Nathan Goldman (discussant), Michelle Harding, Margot Howard, Jing Huang, Haidan Li, Petro Lisowsky, Miguel Minutti-Meza, Dhananjay Nanda, Ken Njoroge, Jane Ou, Marc Picconi, Sundaresh Ramnath, Theodore Sougiannis, Eric Weisbrod, and workshop participants at the 2018 ATA Midyear Meeting, Santa Clara University, University of Illinois, University of Miami, Virginia Tech University, and William and Mary. The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the Gies College of Business and the Kelley School of Business. Professor Rego also appreciates research funding provided by the KPMG Professorship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Variable Definitions

Variable | Definition | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

109_INDICATE | = Indicator variable equal to 1 in the year firm j adopts SFAS 109, and zero otherwise | ProQuest / Mergent Archives |

106_IMPACT | = The absolute value of the cumulative effect adjustment related to SFAS 106 adoption, as reported in firm j’s annual report, scaled by total shares outstanding | ProQuest / Mergent Archives |

BETA | = Fama and French (1993) market model beta for firm j based on monthly returns | Ken French’s website |

DECREASE_DISP | = An indicator set to one if the dispersion of analysts’ earnings forecasts for fiscal year t + 1 made in month m + 1 (where month m is the month the annual report for year t is released) decreased relative to the prior year (i.e., dispersion of analysts’ earnings forecasts for fiscal year t made in month after the annual report for year t-1 is released) | IBES |

DISCR_ACCR | = Discretionary accruals calculated based on the modified-Jones model from Dechow et al. (1995), where discretionary accruals are calculated as the error term (e) from the following cross-sectional OLS regression, estimated by industry and year: Total Accruals = b1 (1 / AT) + b2 (ΔRev – ΔRec) + b3 PPE + e | Compustat |

ETR_VOLATILITY | = The standard deviation of firm j’s GAAP_ETR [tax expense (TXT) scaled by pretax income (PI)] over the three prior years | Compustat |

FIN_LITERATE | = Indicator variable equal to 1 if the individual investor is employed in a “professional” occupation, and zero otherwise | Brokerage Data |

HIGH_ETRVOL | = Indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm-year observation ETR_VOLATILITY value is above the median, and zero otherwise | Compustat |

HIGH_NETDTA | = Indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm-year observation NET_DTA value is above the median, and zero otherwise | Compustat |

HIGH_NOL | = Indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm-year observation NOL_CF value is above the median value for all sample observations with a non-zero value, and zero otherwise | Compustat |

HOLDINGS | = Individual investor i’s average stock holdings in firm j in month m, scaled by investor i’s total stock holdings at the discount brokerage firm in month m, where month m is the month in which firm j files its annual report | Brokerage Data |

ΔHOLDINGS | = The change in individual i’s average stock holdings in firm j from month m-1 to month m + 1 (month m + 3), where month m is the month in which firm j files its annual report | Brokerage Data |

INTANGIBLES | = Total intangible assets (INTAN), scaled by total assets (AT) | Compustat |

INVEST_KNOW | = Indicator variable equal to 1 if the individual investor self-identifies as having good or excellent investment knowledge, and zero otherwise | Brokerage Data |

%INVESTORS | = The percentage of individual investors in the discount brokerage data set that own stock in firm j | Brokerage Data |

Log(#ANALYSTS) | = The natural log of 1 plus the number of analysts following firm j | IBES |

Log(ASSETS) | = The natural log of total assets (AT) | Compustat |

Log(#BSEG) | = The natural log of 1 plus the number of business segments | Compustat |

Log(#GSEG) | = The natural log of 1 plus the number of geographic segments | Compustat |

Log(#ITEMS) | = The natural log of 1 plus the number of missing items in Compustat for firm j | Compustat |

Log(SHARES) | = The log of the number of shares individual investor i holds in firm j | Brokerage Data |

LOSS | = Indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm reports negative income (IB), and zero otherwise | Compustat |

LOW_ETR | = Indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm reports a GAAP ETR in the lowest quintile of all firm-years with requisite data on Compustat, and zero otherwise | Compustat |

LOW_FREQUENCY | = Indicator variable equal to 1 if the individual investor trades less than 48 times in a year, and zero otherwise | Brokerage Data |

MKT_SECURITIES | = Marketable securities adjustment (MSA), scaled by total assets (AT) | Compustat |

MTB | = Market value of equity (PRCC_F*CSHO) divided by book value of equity (CEQ) | Compustat |

NET_DTA | = Following Choudhary et al. (2016), calculated Deferred Tax Assets less Deferred Tax Liabilities, where: Deferred Tax Assets = The long-term portion of the deferred tax asset (TXDBAjt), scaled by total assets (ATjt). Because SFAS 109 permits firms to net their short-term DTAs/DTLs and long-term DTAs/DTLs and in practice many firms net their short-term net DTA/DTL and long-term DTA/DTL, we reset missing values of TXDBjt equal to net DTA/DTL (TXNDBjt) less short-term DTL (TXDBCLjt) less short-term DTA (TXDBCAjt), with missing values of TXDBCLjt (TXDBCAjt) reset to zero when TXDBCAjt (TXDBCLjt) is not equal to missing. If TXDBAjt is missing and TXDBjt is not missing, TXDBAjt is reset to zero Deferred Tax Liabilities = The long-term portion of the deferred tax liability (TXDBjt), scaled by total assets (ATjt). Because SFAS 109 permits firms to net their short-term DTAs/DTLs and long-term DTAs/DTLs and in practice many firms net their short-term net DTA/DTL and long-term DTA/DTL, we reset missing values of TXDBjt equal to net DTA/DTL (TXNDBjt) less short-term DTL (TXDBCLjt) less short-term DTA (TXDBCAjt), with missing values of TXDBCLjt (TXDBCAjt) reset to zero when TXDBCAjt (TXDBCLjt) is not equal to missing. If TXDBjt is missing and TXDBAjt is not missing, TXDBjt is reset to zero | Compustat |

NOL_CF | = Tax loss carryforward (TLCF), scaled by lagged total assets (AT) | Compustat |

PE_RATIO | = Price at the end of the fiscal year (PRCC_F), scaled by earnings per share (NI/CSHO) | Compustat |

σ(PRETAX_ROA) | = Standard deviation over the prior five years of firm j’s pre-tax earnings (PI), scaled by lagged total assets (AT) | Compustat |

PRETAX_ROA | = Pre-tax earnings (PI), scaled by lagged total assets (AT) | Compustat |

RANDOM_POST109 | = A random fiscal year during the sample period but after a firm adopts SFAS 109 | Randomly Generated |

RANDOM_YEAR | = A random fiscal year during the sample period, except for the year of SFAS 109 adoption | Randomly Generated |

R&D | = Total research and development expense (XRD), scaled by lagged total assets (AT) | Compustat |

σ(RETURNS) | = Standard deviation of firm j’s monthly stock returns (RET) over the prior year | CRSP |

RETURNS | = Annual return for the year ending in month m (release of the annual report) | CRSP |

S&P 500 | = Indicator variable set to 1 if the firm is in the S&P 500, and zero otherwise | Compustat |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hutchens, M., Rego, S.O. & Williams, B. The impact of standard setting on individual investors: evidence from SFAS 109. Rev Account Stud 29, 1407–1455 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-022-09740-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-022-09740-x